Abstract

For people living with multiple sclerosis (MS), one’s own body may no longer be taken for granted but may become instead an insistent presence. In this article, we describe how the body experience of people with MS can reflect an ongoing oscillation between four experiential dimensions: bodily uncertainty, having a precious body, being a different body, and the mindful body. People with MS can become engaged in a mode of permanent bodily alertness and may demonstrate adaptive responses to their ill body. In contrast to many studies on health and illness, our study shows that the presence of the body may not necessarily result in alienation or discomfort. By focusing the attention on the body, a sense of well-being can be cultivated and the negative effects of MS only temporarily dominate experience. Rather than aiming at bodily dis-appearance, health care professionals should therefore consider ways to support bodily eu-appearance.

Keywords: multiple-sclerosis, phenomenology, embodiment, lived experiences, qualitative, interview, the Netherlands

Introduction

Because the body is the point of view on which there cannot be a point of view, there is on the level of the unreflective consciousness no consciousness of the body. The body belongs then to the structures of the non-thetic self-consciousness (. . .). Non-positional consciousness is consciousness (of the) body as being that which it surmounts and nihilates by making itself consciousness—i.e., as being something which consciousness is without having to be (. . .) the body is the neglected, the “passed by in silence.” And yet the body is what this consciousness is, it is not even anything except the body. The rest is nothingness and silence. (Sartre, 1943/2003, pp. 353–354)

The healthy body is by various phenomenological scholars described in terms of transparency. Usually, the object of our attention is not our body but what we (can) do with our body, that is, the tasks we are engaged in. The fundamental bodily experience of health is one of harmony, control, and predictability (Carel, 2016, p. 55). Our body, as it were, coincides with what we do and we have a pre-reflective sense of certainty that our body, as we move through the world, will simply “follow” the way we move. Phenomenological studies have described how the body becomes present through illness. This presence of the body is generally qualified as negative and characterized by objectification, alienation, and uncanniness (e.g., Finlay, 2003; Svenaeus, 2000; Toombs, 1987).

Our study examines the bodily experiences of people with multiple sclerosis (MS). MS is a chronic neurological disease that usually hits people in their mid-20s or 30s and which may affect the functioning of many parts of the body (Compston & Coles, 2008). Generally, people with MS suffer from fatigue, numbness, tingling, weakness in one or more limbs, loss of balance, cognitive difficulties, and bladder problems. MS is characterized by a variable and usually a degenerative course. This study focuses on people with relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS), which is characterized by periodic disease exacerbations. The timing of relapses is typically unknown, and the extent to which they will result in residual symptoms is often equally unclear (Alschuler & Beier, 2015).

Hitherto, how people deal with MS has mainly been approached from a (neuro)psychological perspective. Psychological constructs such as coping, adaptation, mood, and hope are considered better predictors of adjustment to MS than illness related factors, for instance, remission status or the severity of symptoms (Irvine, Davidson, Hoy, & Lowe-Strong, 2009; Milanlioglu et al., 2014; Soundy, Roskell, Elder, Collett, & Dawes, 2016). We recognize the value of these studies in that they have shown that despite the negative impact of the disease, it is possible for MS patients to positively influence their well-being. However, we notice one significant drawback. Most of these studies strongly reflect a body-mind dualism and approach processes of adjusting to MS as merely taking place in the mind without thematizing someone’s relation to their own body. In fact, the body is characterized as meaningless material. The problem with dualism is that one is always subordinate to the other. In this case, the strong focus on attitude is at the expense of attention to the body with MS. This does not do justice to the lived reality of people with RRMS who have to deal with their ever-changing body.

A phenomenological approach enables us to study how people with MS deal with their body on a daily basis. Kay Toombs (1992, 1995, 2001), an influential philosopher in the field of phenomenology and medicine and suffering from MS, has written on the phenomenology of MS and the general features of illness as lived. She states that a biomedical description of MS captures little, if anything, of her actual experience of bodily disorder:

I do not experience the lesion(s) in my brain. Indeed, I do not even experience my disorder as a matter of abnormal reflexes. Rather, my illness is the impossibility of taking a walk around the bloc, of climbing the stairs to reach the second floor in my house, or of carrying a cup of coffee from the kitchen to the den. (Toombs, 2001, p. 247)

Miller (1997) studied the lived experiences of people with RRMS and found that uncertainty is an essential part of these experiences as well as the learning process of getting to know the disease. The majority of the phenomenological studies on MS tend to focus on the first period of the disease: the diagnosis and the first years of living with the disease (e.g., De Ceuninck van Capelle, Visser, & Vosman, 2016; Edwards, Barlow, & Turner, 2008; Finlay, 2003). These studies reveal a profound sense of bodily alienation. A synthesis of qualitative research findings shows that living with chronic illness can be understood as an ongoing, continually shifting process (Paterson, 2001). This suggests that experiences of the body in MS may change over time. For this study, we were therefore interested in how people who had been diagnosed with MS for some time, experience their body in daily life. More insight into these experiences may give invaluable information about the everyday world of people with MS and may as such provide directions for health care to enhance well-being in people with MS.

Method

Study Design

Our study followed a phenomenological research design. Phenomenology refers to a tradition of philosophy that originated in Europe and includes the work of Husserl, Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty, Sartre, and many others. In our “doing” of phenomenology, we mainly build upon the work of Max van Manen (2002, 2014) and his phenomenology of practice. This is a context sensitive form of interpretive inquiry representing a blending of phenomenological philosophy with qualitative empirical methods. Van Manen’s approach can be characterized by its emphasis on writing and the use of phenomenological literature in the process of understanding (van Manen, 2017b). According to him, writing is the very act of making contact with the world and phenomenological reflection can therefore not be separated from phenomenological writing (2014, p. 365). Phenomenological literature may aid in the reflective interpretative process by widening our horizon for interpretation (2014, p. 324).

van Manen (2017a) understands the phenomenological method not as a controlled set of procedures but as a way toward human understanding. Hence, he does not identify a series of steps that researchers have to go through during their research. In the following, we describe in detail how we conducted the study and we subsequently provide illustrations to our findings demonstrating the soundness of our interpretative processes to enhance the validity of our study (van Manen, 2014, p. 348). The reduction is a central element in phenomenological research and refers to both a certain attitude and a technique that is used to become reflectively aware of our assumptions and to hold them at bay so that the phenomenon can show itself. Throughout the whole research process, we kept an online “reflexive journal”1 in which we described and reflected upon our interview experiences, assumptions, thoughts, and insights gained from reading literature or other sources to keep an attitude of wonder and openness. Regular meetings in which insights were discussed also contributed to this goal. Concreteness was mainly pursued in our writing which will be described further below. Although in this method section we describe the data collection and analysis separately, in our study, the act of interviewing, listening to the audio recordings, reading the transcripts, and writing alternated, with reflection and understanding as a continuous process.

Recruitment and Interviewing

The Medical Ethical Committee Brabant approved all study procedures. Recruitment took place through a call for participation that was posted on the webpage of the National MS foundation. Potential participants were provided with a detailed information sheet. Totally, 13 people with RRMS were interviewed, all were women. This number was gradually determined because an exact sample size cannot be decided before a phenomenological project is running (Dahlberg, Dahlberg, & Nystrom, 2008, p. 175). The experiential quality of the interviews is a critical condition for the possibility of proper phenomenological reflection and analysis (van Manen, 2014, 2017). All participants provided written informed consent for the interview study. The interviews were conducted by Hanneke van der Meide, Truus Teunissen, and Pascal Collard. The participants could indicate their preference for the interview location. Nine interviews were conducted at the homes of the participants, one in a coffee bar, and three via Skype or FaceTime. The interviews lasted between 35 min and 1hr 55 min.

We prepared interview questions that acted as a guide and supported the participant to remain focused on the phenomenon of interest (interview guide as supplementary material). To gain concrete lived experience descriptions rather than abstract generalizations, we asked how the body was experienced in actual events inviting the participants to share a detailed experiential account of a moment in a particular place in time (Finlay, 2011; Slatman, 2014; van Manen, 2014). During the unfolded conversations and to deepen the accounts, we asked follow up questions like What happened?—What have you done?—What did you experience? How did you feel?—How did it go?—Who was involved and how? Upon their completion, a student assistant transcribed the interviews verbatim with all identifiable information removed from the transcripts.

Data Analysis

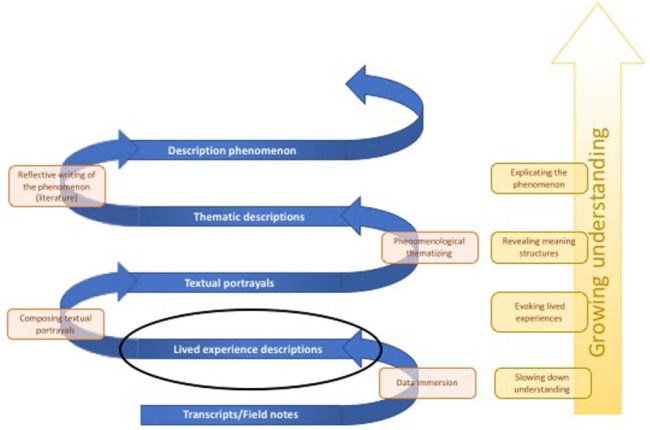

The goal of phenomenological analysis is opening up meanings. Disclosing meaning cannot be forced but can be stimulated by reflective methods in which a state of receptive passivity is adopted (van Manen, 2002, p. 249). Our analysis consisted of four reflective methods that are visualized in Figure 1 and which can be understood as “thinking movements” that lead to a growing understanding: immersion in lived experiences; composing textual portrayals, phenomenological thematization; and reflective writing. The open end in the figure reflects that the gained understanding is always partial and that the phenomenon always remains open to other interpretations.

Figure 1.

Phenomenological analysis.

The analysis was done by Hanneke van der Meide, Truus Teunissen, and Pascal Collard as a joint process. We pursued immersion in lived experiences by reading the transcripts and listening to the audio files. By not doing anything actively immediately, we suspended our understanding and we remained receptive. After reading the transcripts as a whole, we read each transcript again, but with a focus on each sentence or a number of sentences separately. We wrote down our own thoughts, questions, and comments in the margin to surface our preunderstanding. Our preunderstanding refers to the understanding we already have of the phenomenon and includes, among others, our presuppositions, our traditions, the expectations and hopes we have with regard to the study (outcome). The kind of sensitivity that we pursued involved “neither ‘neutrality’ with respect to content nor the extinction of our self, but the foregrounding and appropriation of our fore-meanings and prejudices” (Gadamer, 1995/2004, pp. 271–272). Our aim was to become aware of our own bias, so that the text could present itself in all its otherness.

Reading the transcripts, it became clear to us that not all text was suitable for a phenomenological analysis which requires concrete, lived experience descriptions. Participants also talked about issues that were not related to bodily experiences, shared factual information, their judgments, or reflections on their experiences. In the next step, therefore, we identified lived experience descriptions that would form the basis of our analysis. These lived experience descriptions were used to compose textual portrayals. van Manen (2014) refers to this process of rewriting experiential descriptions as crafting anecdotes. Textual portrayals are short text fragments that describe an aspect of the experience in a language that speaks to our imagination and provide as such a glimpse into the phenomenon. The lived experience descriptions that we used for the textual portrayals did not necessarily follow each other chronologically in the transcript because the same experience was sometimes discussed at different times in the conversation. The actual content was changed by adjustments such as the insertion of linking sentences, the conversion of the text to present time, and the use of personal pronouns, to make the phenomenological content more evocative (Crowther, Ironside, Spence, & Smythe, 2016; van Manen, 2014, p. 250).

The textual portrayals formed the basis of a phenomenological thematization that was aimed at revealing the structures of meaning in the experiences. To that end, the textual portrayals were being read in two ways: a wholistic reading and a detailed reading. In the wholistic reading, we focused on the meaning of the portrayal as a whole. In the detailed reading, we searched for sentences and words that seemed to particularly reveal this meaning. While these readings partly overlap, the double reading promoted thorough reflection on meaning. The themes were identified and grouped with the aid of qualitative software ATLAS.ti. (version 1.0.49 Berlin, Germany). Although the use of qualitative software in Van Manen’s articulation of phenomenological analysis is not typical, we found it helpful to order the large amount of data and it enabled us to do a part of the analysis remotely. The themes were further finalized by means of reflective writing, aimed at disclosing the phenomenon.

Results

The following text provides a detailed description of the bodily experiences of people with MS in discussion with the philosophical literature. The textual portrayals are presented in italics.

Bodily Uncertainty

For a person with MS the body may not any longer function as a matter of course. It occurred to me that I suddenly could not move my legs anymore. I just stood still. It did not hurt but suddenly it stopped, it just did not work anymore. So, I had to call my husband to pick me up. The body used to be an unconscious certainty, the foundation of all actions. We do not normally question that our body will continue to function in a similar fashion to the way in which it has in the past (Carel, 2016, p. 89). In MS, the subtle feeling of “ability” that was once the basis of all actions from ordinary walking to keeping the attention on the conversation, is often accompanied by a sense of uncertainty. This is because of situations in which the body acts differently than is (unconsciously) expected. I was walking with my two dogs. I was completely sober and the dogs just stood still. I made a small step backward but that didn’t go well and I just flipped straight backward. I only felt it when I was halfway through the fall.

The repeated occurrence of this kind of situations disturbs the certainty of “I can.” The experience of suddenly falling happened to this lady more often after this event. Some months after this fall, I participated in a Christmas run and I decided to start last because I didn’t want to fall into that crowd, I just didn’t want it. The tacit certainty about the ability of her body that her legs will carry her has thus given way to bodily uncertainty affecting her sense of bodily trust. In people with MS, the notion of “I can” may shift to an “I might be able to” as the possibility of nonability is now present in the experience. After all, there is always the chance that the body just goes its own way. This bodily doubt may appear gradual but might as well suddenly come upon someone. MS fatigue was always like a blanket of fatigue that suddenly wrapped around me. I was once in a crowded bus and there was no seat left so I had to stand. Suddenly I was surprised by fatigue but I couldn’t ask someone to stood up for me because I looked completely normal. This woman, like several others in our study, tells that MS medication can stretch or slow the tipping point resulting in the feeling that the body has become slightly more predictable.

Bodily experiences, which initially seem bizarre and extraordinary, may become quotidian. I still remember the first time that I experienced muscle spasms in my arm and leg. I could no longer walk or sit normally. I just did not know what happened to me and what my body was doing. It scared me and made me wondering whether it really was my body as I felt totally disconnected from my body. Now I know that spasms are part of my relapses and that they can last for a few weeks. Experiencing a symptom for the first time is entirely different from experiencing the same symptom after many years of living with MS. Someone can become familiar with the strangeness of her body. However, bodily certainty can only partly be regained as the expectations that doubts may return substantively changes the kind of experience involved in each case (Carel, 2016, p. 93). The uncertainty relates to specific aspects of bodily functioning without calling into question other interrelated aspects of bodily existence. It is the arm that suddenly does not move or the leg that trembles and it is not the body as a whole but parts of the body that feel strange and beyond the control of the person. Because of this specificity, the body with MS is not constantly experienced as a limitation, it limits when someone wants to do something that she is unable to.

I have a family day next Tuesday and Friday is my husband’s birthday. That will be a busy weekend for me and I know I will feel that in the following days so I’ve nothing planned for Sunday and Monday because I know I will have to recover. The uncertainty and unpredictability of the body encourages a person with MS to plan her daily life and even joyful moments require conscious thinking beforehand. Planning takes on a completely different meaning than before MS. Where in health the project dominates the action, I walk until I have enough of it, now the action is determined (and often limited) by the body, I walk as long as my body can. The body thus mediates what is done while it formerly mainly performed. This mediation results in a loss of spontaneity. I had bought tickets for a concert of Fish on a whim without thinking about the location. I forgot the MS for a while. When I arrived at the concert hall in my wheelchair the concert turned out to be in hall upstairs and there was no lift. For safety reasons I was not allowed to go up in the first instance. Eventually I was allowed but it remains a bad memory. I felt terribly unhappy and unwanted. I’ve learned from this experience, though. Ever since when I want to go to a concert, I check everything, whether I can take my wheelchair or may walker, that sort of things. Even ordinary tasks require now planning and attention to detail. Yesterday I had to get groceries. I did not go during lunchtime because I know it’s busy with schoolkids at that time. A person with MS can have a hard time in the supermarket because of sounds like a loud radio, talking people, screaming children and the cacophony of scanners. All this might cause sensory overload resulting in experiencing confusion or fatigue.

Having a Precious Body

I bodily experienced my MS for the first time while dancing. My body felt weird. I had exactly in my mind what I wanted, but my body responded with a delay. I could not do it anymore as I had in mind. The plan didn’t match the performance, while I knew exactly how it should be done and which steps I had to take. Because the possibilities of the body might not always match the aspirations of the self, they do no longer coincide in experience. The former immediacy between body and self is shattered by constraint. Yesterday the weather was lovely and I felt good so I wanted to walk a bit. I was just on my way while I noticed that my body didn’t want to go further while I really felt like walking and wanted to continue. I literally experienced my body as a brake. I wanted faster and longer than my body wanted, so I had to switch my mind back to follow the pace that my body indicated.

People with MS might talk about their body as being separated from the self. I see my body and mind as two separate identities. My mind has to take care of my body, whereas it used to be that my mind simply gave the commands and my body followed. My body now limits me in what I can do. In this example, the woman becomes conscious of something in herself giving rise to “the internal distinction between that part (of the self) which gives to the phenomenon the meaning ‘constraint’ and that part (the body) which is felt to be the origin or site of the phenomenon experienced as constraint” (Gadow, 1980, p. 174). In this textual portrayal an opposition between body and mind is suggested. In the West, there has been a tendency to identify the essential self with the incorporeal mind, the body relegated to an oppositional moment (Leder, 1990, p. 69). This tendency can be phenomenologically understood because a certain mode of disappearance is essential to the body’s functioning as an ecstatic—that which stands out—being-in-the-world. Sartre has described our default body functioning in an exemplary manner in the quote presented at the beginning of this article.

I once had a relapse and I had to learn to swallow again. Swallowing is something that you normally do not think about. And I had to learn that all over again. I had to apply certain techniques which I still use to prevent myself from choking. Throughout most of the time our awareness of swallowing is virtually nonexistent. The body only seizes the attention when we can no longer just act from the body, but when we must act toward it. The process of objectification, a focus on the material body, may result in a “re-viewing” of the body. Although the body was never fully eradicated from experience, in MS a person may become explicitly aware of the presence of her body. The phenomenological concepts of body image and body schema enable us to understand this explicit appearance of the body in experience. The body image consists of a complex set of intentional states and dispositions, perceptions, beliefs, and attitudes, in which the intentional object is one’s own body (Gallagher, 2005, p. 25). Although a certain degree of consciousness is implied, usually we are not fully aware of how we perceive our own body. The body image should be distinguished from “body schema” which refers to “a system of sensory-motor capacities that function without awareness or the necessity of perceptual monitoring” (Gallagher, 2005, p. 24). Gallagher illustrates this by the situation when we reach out for a glass, than our hand shapes itself, in a close-to-automatic way, for picking up the glass. In the case that we would perceptually monitor this action, the hand in movement would become part of the body image. This happens in the above example of swallowing. While normally, body image and body schema work together and form one integrated system, in MS they diverge.

My mind likes to be dominant over my body. And now my body gets more chance to speak, there is more balance. I’ve come to realize that I have to pay attention to my body. Because of the MS, I have been forced to look for more balance. Yesterday someone asked me how I was doing and I answered, to my own surprise, that I’m a happy person in a faltering body. We notice, that a person with MS because of attending to her material body, may (re)value this dimension of her body. Someone with MS can (still) talk about her body in appreciative terms. The self is no longer (unconsciously) acting upon the body but is taking care of the body. We could argue that a person with MS “splits” her body to reconnect with her body. This can be understood by one sort of intentional content of the body image, namely, the body affect. The body affect refers to someone’s emotional attitude toward his or her own body (Gallagher, 2005). Because of situations in which the person with MS experience an inability to act as desired, she becomes consciously aware of what the body does enable her to do (in all those other situations) in daily life. The emotional attitude of a person with MS toward her body can be described as one of care and she is committed to keep her body in shape by means of, for example, exercising, and paying attention to her diet. Although some people used to do this already before the onset of the disease, they do it now more consciously. From a phenomenological point of view, there is no dualism between the mind and the body in MS but there appears a disintegration of the body image and body schema.

A reappreciation of the body does not imply that a person with MS is always happy with her body and that “carrying it along” (Merleau-Ponty, 1945/2004) is something easy. Recognizing the body implicates that it is a deliberative focal point of attention. A person with MS may refuse to be limited by their body and thereby enacting her freedom despite of her body’s limitations. In some cases, they may even harm their body to nourish their soul. We go to the sauna every Friday evening. After the sauna, I always have weak legs and I know the heat is not good for my body but my spiritual well-being is also important. Going to the sauna is my way of unwinding.

Being a Different Body

My lower leg and my left arm feel numb. It’s like I do not feel myself. As if I’m wearing thick ski socks. When I dry off other parts of my body, it feels different. It’s like I dry off my neighbor’s leg, it feels far away. It’s like I wear jeans around my legs all the time. Now, after 14 years of washing and drying off and getting the input of that other feeling again and again, it starts becoming familiar. Slowly I think, my legs feel like that, I’m losing the old feeling and they become my own legs more and more. A person with MS is engaged in the process of building up a modified habitual body. Merleau-Ponty (1945/2004) distinguishes the habitual body from the actual or the present body. The former signifies the body as it has been lived in the past, in virtue of which it has acquired certain habitual ways of relating to the world. With its “two layers” the body is the meeting place of past, present and future because it is the carrying forward of the past in the outlining of the future and the living of this bodily momentum as actual present (Langer, 1989). The body as it has been lived in the past, what it was capable of and how it felt, has changed. As time passes, the past experience of the body gets faded and the person has to become familiar with her “new” body. The body does not only feel differently than before the disease, its possibilities have also been altered and a person with MS must modify her actions. This can be difficult because the body is not only our medium to act in the world but also to express ourselves. To me, dancing was always a way to express myself. As it now has been long ago that I could dance my feeling is actually more a kind of longing for the past. As with MS the body continues to change, the process of building up a modified habitual body can be seen as infinite implying that a sense of familiarity is always preliminary.

In September, I had to learn to walk again. First a few steps, then a short walk and each time a bit further. I felt very miserable that time because a lot of people in my neighborhood do not know that I have MS. I had the feeling that everyone was peeking through the window seeing me acting weird. I walked like a woman of 80. I really worried what they might think of it but yeah, I wanted to recover and moving around was the only way to get there. The look of the other intensifies someone’s subjectivity. “I exist for myself as a body known by the Other,” as Sartre (1943/2003, p. 375) puts it. The other’s gaze reifies or corporealizes the lived-body. Recently I was at the cash desk and my arm started to move. That was of course inconvenient since I had to grab money and hand it over to the cashier. I became very social, very friendly, and attentive to the cashier and the bystanders. I started talking and making jokes about my arm. Both the visibility and the invisibility of the disease give a person with MS the feeling that she has to justify herself to others. This feeling may be enforced by the variation in symptoms as the person with MS understands that this might be confusing to others.

Recently, I went to the park on a weekday. Since I don’t work, I can do fun things. But I felt guilty because I can go to the park for a nice picnic on a weekday while others are at work. That’s not how it should be. So, it sounds like fun, but it is not fun. The manner in which one apprehends one’s body reflects the particular lifeworld in which one is situated. Schmitz’ notion of an “abstraction base” refers to a set of fundamental ideas or concepts so deeply entrenched in common experience that they provide a framework of intelligibility in which all things appear in experience and shape how they are understood and interpreted (Schmitz, Mullan, & Slaby, 2011, p. 244). For people with MS the idea of being “a productive body”2—doing something useful for society—can be seen as a contemporary abstraction base.

The Mindful Body

Yesterday I walked in the city center and did some shopping. I noticed that my legs started to swing and that I was more and more leaning against the person I was with. Then I realized it was time to go home. It is against the background of bodily uncertainty, the (re)appreciation of the body and the feeling of being a different body that a person with MS may find herself almost always in a mode of permanent bodily alertness. We call this “the mindful body” referring to an unremitting and receptive focus on one’s material body. I notice that I’m in a relapse now because my right arm feels very heavy. It feels like I have been carrying groceries for a long time or holding a child on my arm. My shoulders feel terrible and it bothers me while cycling. I also have sensory disturbances in my legs. It feels like my legs are covered with Midalgan and wrapped very tightly with ductape. So I know I have to take it easy these days, some weeks perhaps. The focus on one’s body may enable people with MS to live as well as possible with MS because the bodily limits are recognized in time.

Last night I had a good time with friends until I noticed that I started to have trouble with talking. That’s always the first sign and I knew that I had to take it easy, that I better did not have another drink so I went home. A person with MS might talk about “listening to her body.” She may especially be sensitive to signals of fatigue, which often appears through the malfunctioning of certain bodily functions such as sensory disturbances, trouble with communicating or concentrating. The signals differ but are often characteristic of the person in question. A person with MS has to relearn to feel her body and its signals and may experience that she is her body. The body, in the words of Merleau-Ponty (1945/2004), is an expressive unity which can only be learned to know by actively taking it up. By “remaking contact with the body and with the world, we shall also rediscover ourself, since, perceiving as we do with our body, the body is a natural self and, as it were, the subject of perception” (p. 239). We might argue that someone with MS is almost constantly consciously and unconsciously connecting with her body. Especially in the morning this is a conscious act. I consciously sense all my body parts every morning. I sense if everything still works and whether I still feel everything. Every morning the same ritual, immediately when I wake up. I do it almost automatically. And only when I’m convinced that it’s going well, I go out and the day starts. I then adjust my plans for the day to how my body feels.

A person with MS may attempt to (re)connect with her body by monitoring and sensing its state. In monitoring, attention is focused on the body whereas in sensing, attention is drawn to the body. The first refers to an active act while the latter has a more passive quality as the physical sensations that a person undergoes and becomes aware of. Physical sensations are independent of how one relates to them: they simply come and go (Schmitz, 2008). Bodily alertness implies that reflection is involved in almost everything someone does.

Last week someone asked me to describe what MS was like. I responded by saying that MS is like the weather as I cannot predict how I will feel in 3 days, or tomorrow or even in a few hours. Despite the attempt to connect with the body, a person with MS will never fathom her own body as “that which operates via self-effacement, the lived body can never be a fully explicit thing” (Leder, 1990, p. 17). Someone with MS must confide herself to her (unpredictable) body. Schmitz (2008, p. 49) states that “mankind must learn to confide itself to the fate of physicality with all chances and defects.” He uses the image of a rider on a horse to describe the relation between a person and her body contrary to Plato who refers to a rider and a chariot. Instead of mastering the body, the image that appears in the experiences of people with MS, is the body as a sensitive source of information. Schmitz talks about the body as a “sensitive counselor.” The sensations to the body have something to say to the person. In the following, we will show that in some situations the mindful body can be put on hold, temporarily releasing the state of alertness.

Corporeal Contraction

This afternoon I have terrible pain in my legs, nerve pain. I cannot concentrate on anything other than my body. This pain cannot be tempered and I do not know where to look for. I endure the pain and wait until it goes away. I know that I will be very tired tomorrow. Then all the energy goes to my legs. On such a day, I feel total loss, just like healthy people the day after running a marathon. I cannot study and I try to distract myself by messing around, reading something, watching television and waiting, because I know it will end. There are situations in which the person with MS endured erratic and intense bodily sensations. Following Schmitz et al. (2011, p. 245), we call this experience corporeal contraction as the body draws full attention and takes control. Corporeal contraction refers to a marked narrowing of the felt body. This may occur in the case of a relapse or with severe fatigue. In the above example, the woman is totally focused on her bodily sensations that are strange and intrusive. The so-called MS hug, a common symptom in MS, is another example of corporeal contraction. I have the MS hug, which is a strap around the chest getting worse, during the day. The MS hug is a feeling in my body. It’s like having an elastic around my wrist that gets tighter. At that moment, my body enters a warning phase, like it says: don’t do any crazy things anymore because otherwise we’re going to tighten it even more! I’ve had periods that I was at home in the evening and that it felt like my lungs were pulled together and I could hardly breathe anymore. It feels like I cannot breathe but it has nothing to do with my lungs, it is a very persistent sensory symptom.

Corporeal Expansion

I am completely relaxed while dancing and while doing physiotherapy. These are very short moments when I am not aware of my complaints. I feel so good that I don’t experience symptoms. Maybe I have them but I do not feel the pain in my legs or the throbbing headache. It is all on the pause button and get some rest from my broken body. A person with MS might as well experience a sense of well-being through her body. Following Schmitz et al. (2011, p. 245), we call this experience corporeal expansion referring to “a marked widening of the felt space in the region of one’s body, most notably occurring in a state of relaxation.” People with MS describe situations of practicing physical exercise in which they consciously experience their body in a positive way. We might argue that in these situations, body image and body schema form an integrated system again. The body temporarily functions in a close-to-automatic way. I had spinning class a few days ago. During the first song when cycling, my legs felt heavy. But at a certain moment I was so in the flow of the lesson and busy with the group in front of me, that my body fell away.

Discussion

In this article, we have presented a phenomenology of the body with MS. Our study shows the body as an insistent presence in the daily experiences of people with MS. We have described the various modes in which the body may appear. Although the dimensions interrelate, describing them separately allows us to stress the different meanings the body can take.

The experience of uncertainty is widely described in studies on MS from various perspectives (e.g., Alschuler & Beier, 2015; Courts, Buchanan, & Werstlein, 2004; Dennison, Smith, Bradbury, & Galea, 2016; Krahn, 2013; Olsson, Lexell, & Söderberg, 2008). From a phenomenological view, Toombs (2001) states that some of the uncertainty experienced in degenerative diseases relates to the fact one has to learn and relearn how to negotiate the surrounding world on an ongoing basis. The “I can do it again” can never be taken for granted (p. 251). Finlay (2003) argues that the diagnosis of MS results in a sense of nondeterminacy and global uncertainty permeating someone’s life. Our findings highlight the uncertainty that directly refers to the body in the here and now and less to the (prognostic) uncertainty in the long-term. This can probably best be explained by our interview approach. Carel (2016) describes bodily doubt as a core experience of every serious illness and suggests that bodily doubt constitutes the transition from health (bodily capacity) to illness (bodily incapacity). She stresses that bodily doubt “is not solely cognitive but that it is experienced as anxiety on a physical level, hesitation with respect to movement and action, and a deep disturbance of existential feeling” (p. 96). She provides examples that are similar to our findings. She shows, for instance, that bodily uncertainty requires continuous planning, loss of spontaneity, loss of faith in one’s body and that it leads to a shift of attention to one’s body instead of or besides the attention to the project that is carried out by the body. What our study adds, however, is that the uncertainty of the body and the associated presence of the body is not only accompanied by negative feelings such as anxiety, fear, and concern.

The objectification of the (own) body is usually valued negatively and following Sartre’s train of thought, described as a process of self-alienation. Leder (1990) states that disease constitutes a negative appearance—dysappearance of the body. The Greek prefix “dys” signifies “bad,” “hard,” or “ill” (p. 84). Dys-appearance takes place when the body appears to me as “ill” or “distressing.” Zeiler (2010) notes that it is a priori assumed that attention to one’s body primarily or only implies alienation. Most phenomenological studies reverberate the idea that the less the body is present, the healthier and the more capable it is (Slatman, 2016). The multitude of phenomenological studies describing the dys-appearance of the body in illness play in this way, probably unintentionally, a part in buttressing Cartesian dualism (Leder, 1990). In other words, the “absent” body is prioritized. Our study shows that people with MS demonstrate adaptive responses to their ill body enabling them to get used to radically different forms of embodiment. The body with MS, with exception of corporeal contraction, is not entirely opaque or obstructive in illness and bodily enjoyment is still possible. The negative effects of MS are transient and only temporarily dominate experience. Our findings correspond to Miller’s (1997) suggestion that continuous and unpredictable uncertainty may lead the person to reappraise the uncertainty as less threatening and over time, the uncertainty might become an opportunity to be healthy rather than ill (p. 302).

The awareness of the body is “a profoundly social thing, arising out of experiences of the corporeality of other people and of their gaze directed back upon me” (Leder, 1990, p. 92). The sense of “being observed by the glance of the other” (Sartre, 1943/2003) is reflected in our study in the experience of being “an unproductive body.” Contemporary Western society is typified by “hyper pace”: everyday work requires people to speed up constantly, with little opportunity to slow down (Vosman & Niemeijer, 2017). Miller (1997) describes that people with MS often conceal their illness from a society that does not understand. We have described a similar struggle between concealing and revealing bodily experiences. Many people with MS struggle as well with the need of listening to their body and living up to social expectations. Our society is a “planning society” in which we schedule appointments weeks ahead. This is at odds with the tendency of a person with MS to live in the now, in which decisions on what to do are based on how the body feels and what it can do rather than on an agenda. The discussion of the corporeal contraction and expansion might be typical of an episodic condition such as RRMS and it should be further studied whether this experience also applies to other types of MS.

Our study contains several implications for health care. Care professionals often seek to soften bodily dys-appearance by enabling bodily dis-appearance for patients (Zeiler, 2010). In dis-appearance, the body simply does not appear. This can be pursued by, for example, pain medication but also by (psychological) interventions that suggest that the self can control or ignore the body through, for example, a change in attitude. From a dualistic perspective, the response to a faltering body is finding ways to control the body because the other option seems to give in to the disease. In either case, the relation between body and self is one of implicit struggle (Gadow, 1980). The experiences of the people in MS in our study indicate that health care professionals should consider ways to support bodily eu-appearance in their patients. In eu-appearance, the body stands forth to the subject as good and well-being is experienced through the body. Body-awareness enhancing therapies can be useful in this. Body awareness generally refers to an attentional focus on and awareness of bodily sensations (Mehling et al., 2009). There is preliminary evidence that body awareness-enhancing therapies such as mindfulness, dance, and yoga may be useful in the management of chronic diseases such as fibromyalgia, chronic pain, and rheumatoid arthritis (Gard, 2005; Loof, Johansson, Hendriksson, Lindblad, & Bullington, 2014; Mehling et al., 2011). Rather than controlling the body, these therapies aim to integrate mind and body. A study of Calsius et al. (Calsius et al., 2015) demonstrate that physical exercise might as well contribute to well-being in MS. Before participation in a climbing expedition to Machu Picchu, people with MS experienced their body as a difficult, even uncontrollable thing that often obstructed daily functioning or life with a debilitating influence on their self-identity. Calsius et al. show that during the trip, this condition of dys-appearance was gently countered by experiences of the body as a source of pleasure again. The participants in our study also provided examples of practices such as walking, meditation, and dance, in which they consciously attended to their body in positive way. Our study indicates that well-being in MS is possible, not despite but thanks to the body. The experience of well-being in MS is in that sense no different from that of healthy people.

The description of the various ways the body might appear in MS can initiate reflection in health care professionals on what dimension is central in the concrete patients they encounter. Professionals should be aware that they can aggravate dimensions such as the feeling of being a different body or bodily uncertainty by, for example, the medical focus on merely dysfunction. Moreover, they should support MS patients in their struggle between taking care of their body and living a social and pleasant life. For the time being, bodily uncertainty will remain the hallmark of MS and this experience needs therefore to be discussed in consultations with patients from an existential perspective.

Concluding Remarks

MS is an extraordinarily variable disease in terms of the wide range of manifesting symptoms and the severity and course of the disease, and we may wonder whether we captured “the essence” of the bodily experiences and whether our findings may be generalized. By providing a phenomenologically sensitive account of the various structures of bodily experience, we have attempted to keep the richness and diversity in experiences intact. We acknowledge the unshareability characteristic of illness as it is an inner, rather than an outer event, which, in large part, cannot be shared with another (Toombs, 1992, p. 23). This article should, therefore, be viewed as a modest attempt to reveal a glimpse of the bodily experiences in MS. Furthermore, the participants in our study have RRMS and the episodic character might explain why their body experience reflects an ongoing oscillation between various dimensions. It should be further examined whether this dynamic also applies to other forms of MS.

Only women participated in this study. We assume that the people who signed up for this study were concerned with their body, perhaps more than the “general person with MS.” We, therefore, recommend further research on bodily experiences in people with MS. The experiential dimensions from this study can serve as a good starting point.

Concerning the use of textual portrayals someone might remark that different researchers would have uncovered different textual portrayals. We acknowledge that every revealing has its concealing. We believe, however, that composing textural portrayals are a useful way to look for implicit meanings (Finlay, 2014). Also, textual portrayals enable us to disclose the experience in an evocative manner and meet as such the aspect of resonance which is described as an expression of rigor in phenomenological research (De Witt & Ploeg, 2006; Finlay, 2011).

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Supplementary_material_ for The Mindful Body: A Phenomenology of the Body With Multiple Sclerosis by Hanneke van der Meide, Truus Teunissen, Pascal Collard, Merel Visse and Leo H Visser in Qualitative Health Research

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to all participants in the study. We are indebted to Sanne Rodenburg, who transcribed many hours of recorded interviews.

Author Biographies

Hanneke van der Meide, PhD, is researcher at Tilburg University in Tilburg, The Netherlands.

Truus Teunissen, PhD, is researcher at Amsterdam UMC in Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Pascal Collard, MSc, MA, is junior researcher at the University of Humanistic Studies in Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Merel Visse, PhD, is assistant professor at the University of Humanistic Studies in Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Leo H Visser, PhD, is a professor at the University of Humanistic Studies in Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Following Murray and Holmes (2013), by using reflexivity rather than reflection, we wish to emphasize the active, engaged dimensions of reflexivity. While reflection is generally characterized as a cognitive activity; reflexivity is a dialogical and relational activity. Indeed, we often do not know what we know and we need others to become aware of our preunderstandings and assumptions.

In the context of the Dutch society this might also be framed as “a participating body.” In the Netherlands, the welfare state has been replaced by a “participation society” in which people must take responsibility for their own future and create their own social and financial safety nets, with less help from the national government.

Authors’ Note: Hanneke van der Meide, Merel Visse, and Leo Visser were responsible for the research design and obtaining funding. Hanneke van der Meide, Truus Teunissen, and Pascal Collard conducted the interviews and analysis. Hanneke van der Meide was responsible for the drafting of the manuscript while Truus Teunissen, Merel Visse, and Leo Visser commented on the various drafts, finally leading to this article.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by the National MS Foundation.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental Material for this article is available online at journals.sagepub.com/home/qhr. Please enter the article’s DOI located at the top right hand corner of this article in the search bar, and click on the file folder icon to view.

References

- Alschuler K. N., Beier M. L. (2015). Intolerance of uncertainty. International Journal of MS Care, 17, 153–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calsius J., Courtois I., Feys P., Van Asch P., De Bie J., D’hooghe M. (2015). “How to conquer a mountain with multiple sclerosis.” How a climbing expedition to Machu Picchu affects the way people with multiple sclerosis experience their body and identity: A phenomenological analysis. Disability and Rehabilitation, 37, 2393–2399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carel H. (2016). Phenomenology of illness. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Compston A., Coles A. (2008). Multiple sclerosis. The Lancet, 372, 1502–1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courts N. F., Buchanan E. M., Werstlein P. O. (2004). Focus groups: The lived experience of participants with multiple sclerosis. The Journal of Neuroscience Nursing : Journal of the American Association of Neuroscience Nurses, 36, 42–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowther S., Ironside P., Spence D., Smythe L. (2016). Crafting stories in hermeneutic phenomenology research: A methodological device. Qualitative Health Research, 1(10), 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlberg K., Dahlberg H., Nystrom M. (2008). Reflective lifeworld research. Lund, Sweden: Studentlitteratur. [Google Scholar]

- De Ceuninck van Capelle A., Visser L. H., Vosman F. (2016). Developing patient-centred care for multiple sclerosis (MS). Learning from patient perspectives on the process of MS diagnosis. European Journal for Person Centred Healthcare, 4, 675–680. [Google Scholar]

- Dennison L., Smith E. M., Bradbury K., Galea I. (2016). How do people with Multiple Sclerosis experience prognostic uncertainty and prognosis communication? A qualitative study. PLoS ONE, 11(7), e0158982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Witt L., Ploeg J. (2006). Critical appraisal of rigour in interpretive phenomenological nursing research. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 55, 215–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards R. G., Barlow H. J., Turner A. P. (2008). Experiences of diagnosis and treatment among people with multiple sclerosis. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 14, 460–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay L. (2003). The intertwining of body, self and world: A phenomenological study of living with recently-diagnosed multiple sclerosis. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, 34, 157–178. [Google Scholar]

- Finlay L. (2011). Phenomenology for therapists: Researching the lived world. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Finlay L. (2014). Engaging phenomenological analysis. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 11, 121–141. [Google Scholar]

- Gadamer H. G. (2004). Truth and method (2nd. rev. ed). New York: Continuum. (Original work published 1995) [Google Scholar]

- Gadow S. (1980). Body and self: A dialectic. The Journal of Medicine and Philosophy, 5, 172–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher S. (2005). How the body shapes the mind. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gard G. (2005). Body awareness therapy for patients with fibromyalgia and chronic pain. Disability and Rehabilitation, 27, 725–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine H., Davidson C., Hoy K., Lowe-Strong A. (2009). Psychosocial adjustment to multiple sclerosis: Exploration of identity redefinition. Disability and Rehabilitation, 31, 599–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krahn T. M. (2013). Care ethics for guiding the process of multiple sclerosis diagnosis. Journal of Medical Ethics, 40, 802–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer M. M. (1989). Phenomenology of perception: A guide and commentary. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Leder D. (1990). The absent body. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Loof H., Johansson U. B., Hendriksson E. W., Lindblad S., Bullington J. (2014). Body awareness in persons diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis. Qual Studies on Health and Well-Being, 9, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehling W. E., Gopisetty V., Daubenmier J., Price C. J., Hecht F. M., Stewart A. (2009). Body awareness: Construct and self-report measures. PLoS ONE, 4(5), e5614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehling W. E., Wrubel J., Daubenmier J. J., Price C. J., Kerr C. E., Silow T., . . . Stewart A. L. (2011). Body awareness: A phenomenological inquiry into the common ground of mind-body therapies. Philosophy, Ethics, and Humanities in Medicine, 6(1), Article 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merleau-Ponty M. (2004). Phenomenology of perception (Smith C., Trans.). London: Routledge.(Original work published 1945) [Google Scholar]

- Milanlioglu A., Özdemir P. G., Cilingir V., Gülec T. Ç., Aydin M. N., Tombul T. (2014). Coping strategies and mood profiles in patients with multiple sclerosis. Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria, 72, 490–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller C. M. (1997). The lived experiences of relapsing multiple sclerosis: A phenomenological study. The Journal of Neuroscience Nursing, 29, 294–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray S. J., Holmes D. (2013). Toward a critical ethical reflexivity: Phenomenology and language in maurice merleau-ponty. Bioethics, 27, 341–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson M., Lexell J., Söderberg S. (2008). The meaning of women’s experiences of living with multiple sclerosis. Health Care for Women International, 29, 416–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson B. L. (2001). The shifting perspectives model of chronic illness. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 33, 21–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartre J. P. (2003). Being and nothingness An essay on phenomenological ontology (Barnes H. E., Trans.). London: Routledge. (Original work published 1943) [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz H. (2008). Leib und Gefühl: Materialien zu einer philosophischen Therapeutik. (Body and Feeling: Materials for a Philosophical Therapeutic.) Bielefeld, Germany: Sirius. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz H., Mullan R. O., Slaby J. (2011). Emotions outside the box—The new phenomenology of feeling and corporeality. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 10, 241–259. [Google Scholar]

- Slatman J. (2014). Multiple dimensions of embodiment in medical practices. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 17, 549–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slatman J. (2016). Is it possible to “incorporate” a scar? Revisiting a basic concept in phenomenology. Human Studies, 39, 347–363. [Google Scholar]

- Soundy A., Roskell C., Elder T., Collett J., Dawes H. (2016). The psychological processes of adaptation and hope in patients with multiple sclerosis : A thematic synthesis. Open Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation, 4, 22–47. [Google Scholar]

- Svenaeus F. (2000). The body uncanny-further steps towards a phenomenology of illness. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 3, 125–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toombs S. K. (1987). The meaning of illness: A phenomenological approach to the patient-physician relationship. Journal of Medicine and Philosophy, 12, 219–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toombs S. K. (1992). The meaning of illness: A phenomenological account of the different perspectives of physician and patient. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Toombs S. K. (1995). The lived experience of disability. Human Studies, 18, 9–23. [Google Scholar]

- Toombs S. K. (2001). Reflections on bodily change: The lived experience of disability. In Toomb S. (Ed.), Handbook of phenomenology and mediicine (pp. 247–262). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- van Manen M. (2002). Writing in the dark: Phenomenological studies in interpretive inquiry. London, Ontario, Canada: The Althouse Press. [Google Scholar]

- van Manen M. (2014). Phenomenology of practice. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press. [Google Scholar]

- van Manen M. (2017. a). But is it Phenomenology? Qualitative Health Research, 27, 775–779. doi: 10.1177/1049732317699570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Manen M. (2017. b). Phenomenology in its original sense. Qualitative Health Research, 27, 810–825. doi: 10.1177/1049732317699381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vosman F., Niemeijer A. (2017). Rethinking critical reflection on care: Late modern uncertainty and the implications for care ethics. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 20, 465–476. doi: 10.1007/s11019-017-9766-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeiler K. (2010). A phenomenological analysis of bodily self-awareness in the experience of pain and pleasure: On dys-appearance and eu-appearance. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 13, 333–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, Supplementary_material_ for The Mindful Body: A Phenomenology of the Body With Multiple Sclerosis by Hanneke van der Meide, Truus Teunissen, Pascal Collard, Merel Visse and Leo H Visser in Qualitative Health Research