Abstract

Aim:

This study aimed to evaluate the residual filling material and the reestablishment of working length (WL) and apical patency after retreatment of BioRoot™ RCS, versus TotalFill® BC Sealer, and AH26, used in a single cone obturation technique.

Materials and Methods:

Sixty single-rooted permanent canines were instrumented up to size 40/.04 (Sendoline, Täby, Sweden). The samples were filled with GP/AH26 (Group 1), GP/TotalFill BC Sealer (Group 2), and GP/BioRoot RCS (Group 3). Eight teeth were used in the positive and negative control groups. Canals were retreated using the Protaper Universal retreatment files (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland) and further instrumented up to size 50/.04 (Sendoline, Täby, Sweden). The ability to reestablish WL and apical patency was recorded. Furthermore, the samples were observed under a scanning electron microscope, in order to evaluate the residual filling material. Data were analyzed statistically with the Fisher's exact and the Kruskal–Wallis tests (P < 0.05).

Results:

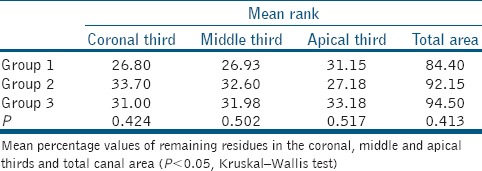

There was no statistically significant difference in the WL and patency recovery among the groups. Neither the intragroup comparison among canal thirds nor the intergroup comparison in each canal third or in total canal area revealed any significant differences in the percentage of the remaining filling material after retreatment.

Conclusion:

Residual material debris was observed in all samples regardless of the sealer used. All the sealers were removed to a similar extent. The WL and patency were reestablished sufficiently in all groups.

Keywords: BC sealer, bioceramics, BioRoot™ RCS, endodontic sealer, retreatment, TotalFill®

INTRODUCTION

Numerous sealers have been used in conjunction with Gutta percha for root canal obturation. Bioceramics, a novel category of high-purity tricalcium silicate sealers, were recently launched and possibly offer certain advantages compared to commonly used sealers.[1] The bond formed between the dentinal walls and the bioceramics after their setting is under investigation.[2] Studies propose a micromechanical anchorage[2] as well as a chemical adherence[3] of the sealer to the dentin substrate. Their unique setting activity and their hardness upon setting may enhance their adhesion and resistance to dislocation from dentin and hinder their efficient removal during the secondary endodontic therapy.[4,5,6,7] The sealer residues constitute a mechanical barrier between the intracanal disinfectants and the microbes of hardly accessible areas such as dentinal tubules and ramifications.[8] Furthermore, their apical retrieval may assist the clinician to attain apical patency, which significantly increases the periradicular healing rates.[9]

A number of studies have tested the removal of bioceramic sealers.[6,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18] However, little is known regarding the retreatability of a newly developed bioceramic material, BioRoot™ RCS (Septodont, Saint Maur des Fossés, France). Modified from Biodentine, this material consists of a fine powder of tricalcium silicate and zirconium oxide and a liquid solution that contains calcium chloride.[7]

The present study evaluated the residual filling material, the reestablishment of working length (WL) and the retrieval of apical patency following the removal of BioRoot RCS used in a single cone obturation technique, considering a premixed bioceramic and an epoxy resin sealer as comparisons. This is the first effort to undertake a microscopy study for evaluation of the residues of BioRoot RCS on the root canal walls after retreatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sixty-eight permanent single-rooted human canines were selected for the study. Teeth were verified with mesiodistal and buccolingual radiographs as having single canals of <20° curvature. Teeth with root fillings, calcifications, immature apices, and resorptive defects were discarded. For disinfection purposes, the teeth were soaked in a 5.25% sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) solution for 10 min and then stored in 0.1% thymol until use. Standardized root specimens of 16 mm length were formed after the trim of the crowns with a double-sided diamond disc and a low-speed handpiece under water coolant. The patency was established by inserting a size 10 K-file (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues Switzerland) into the root canal until the tip was visible at the apical foramen. The WL was calculated by subtracting the file 1 mm from the anatomical apex. All canals were instrumented with rotary files (Sendoline, Täby, Sweden) up to size 40/.04 in a crown-down manner using an X-Smart endodontic motor (Dentsply Maillefer) according to the manufacturers' instructions. The irrigation protocol included 2 ml 2.5% NaOCl between each instrument and a final flush of 5 ml 2.5% NaOCl, followed by 5 ml 17% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid and 5 ml saline. Subsequently, the canals were dried with paper points.

With the aid of a computer algorithm (www.random.org), the samples were randomly divided into three groups (n = 20) according to the sealer used during the root canal obturation.

Group I (n = 20): AH26 sealer (Dentsply Maillefer, Tulsa, USA)

Group II (n = 20): TotalFill® BC Sealer (FKG Dentaire SA, La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland)

Group III (n = 20): BioRoot RCS (Septodont, St. Maur-des-Fossés, France)

Positive control group (n = 6): Equal specimens were obturated with one of the sealers, but no retreatment procedure was applied

Negative control group (n = 2): Two specimens were not obturated and the retreatment procedure was applied.

Except for TotalFill BC Sealer, which is premixed in ready-to-use syringes, the other sealers were mixed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Root canal filling to the WL was carried out with matched tapered Gutta percha points (Sendoline, Täby, Sweden) in a single cone technique. The access of canals was sealed with Cavit-G (3M ESPE, Seefeld, Germany). Mesiodistal and buccolingual radiographs verified the quality of the obturation. The specimens were stored at 37°C in 100% relative humidity for 60 days.

The ProTaper Universal Retreatment D1, D2, and D3 rotary files (PTR; Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland) were used for the removal of the material from the coronal, middle, and apical thirds, respectively. The canals were further instrumented with rotary files up to size 50/.04 (Sendoline, Täby, Sweden). The aforementioned irrigation protocol was applied during the retreatment procedure. All instruments in the study were discarded after they were used five times. The retreatment was considered complete when the last instrument reached the WL and no evident filling material could be seen on the last file. The ability to reach WL and to regain patency were determined using small K-files (6, 8, 10, 15 Dentsply, Maillefer).

The teeth were grooved buccolingually using a diamond bur and then wedged apart longitudinally with a hammer and a chisel. One half of each tooth was randomly selected for the study. Three grooves were prepared in the root surface, with a lancet indicating the coronal (9 mm from the apex), middle (6 mm from the apex), and apical (3 mm from the apex) thirds. One scanning electron microscope (SEM) photomicrograph was taken at the center of the root canal in the aforementioned positions at two magnifications (×100, ×1000). The identification of the material remnants was achieved using energy dispersive spectrometry (EDS) (Inca software, Oxford, UK).

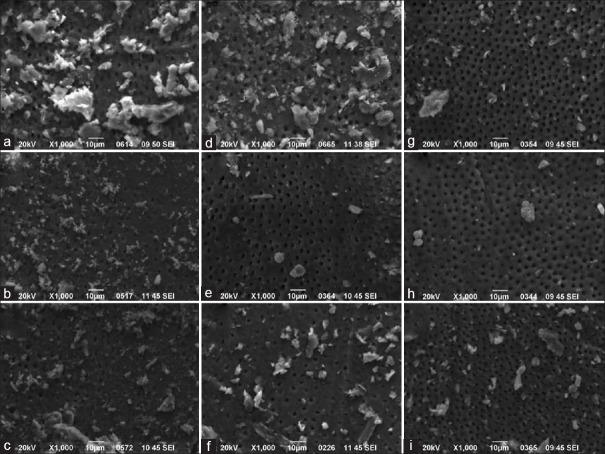

The residual material on the dentin was evaluated using a predefined scale[14] [Figure 1] as follows:

Figure 1.

Representative images of scores assigned to the SEM photomicrographs. (a) Score 1; (b) Score 2; (c) Score 3, (d) Score 4

Score 1: No or slight presence of remnants (0%–25%)

Score 2: Presence of some remnants (25%–50%)

Score 3: Frequent presence of remnants (50%–75%)

Score 4: Remnants present almost everywhere (75%–100%).

A single operator performed all the experimental procedures, while the images were individually assessed blind by two examiners.

Statistical analysis was carried out with SPSS 20.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to identify potential significant differences among the canal thirds of each group, and among the groups in each canal third and in total canal area. The ability to reach WL and to regain patency was analyzed by Fisher's exact tests. P < 0.05 was used to determine significance.

RESULTS

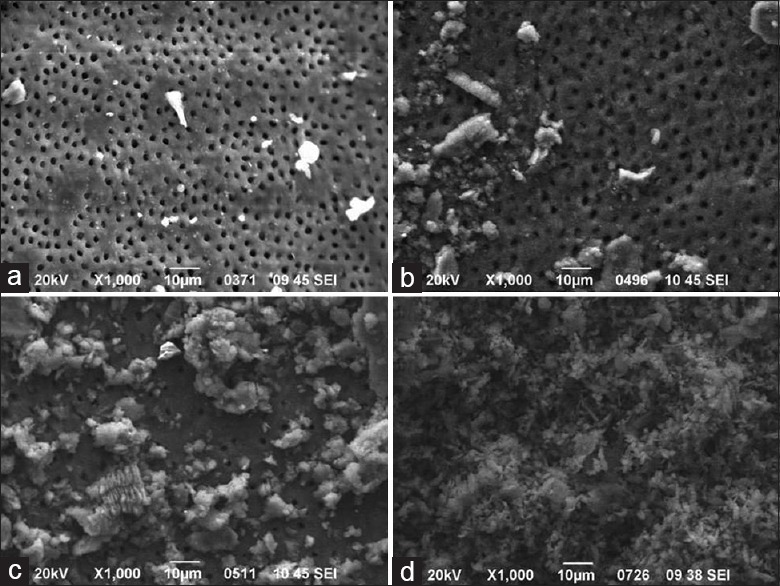

The patency and WL were regained in 95% of the specimens in Group 1 and in 100% of the specimens in Groups 2 and 3. The Fisher's exact test revealed no significant differences either between Groups 1 and 2 or 1 and 3 (P = 1.00). All specimens exhibited filling residues in the root canal walls. The intragroup comparison revealed that the amount of material debris was similar in all canal thirds of each group (Kruskal–Wallis test, P = 0.064 for AH26, P = 0.061 for TotalFill, P = 0.340 for BioRoot RCS). Moreover, there was no statistically significant difference among the groups either in the root canal thirds or in the total canal area (P > 0.05). The results of the intergroup comparison are presented as mean percentage of filling remnants in Table 1. Representative SEM images of each canal third of the three groups are depicted in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Residual root canal filling material for each group

Figure 2.

Representative SEM images of the three groups at ×1000 magnification. Group 1 (a: coronal third; b: middle third; c: apical third), Group 2 (d: coronal third; e: middle third; f: apical third), Group 3 (g: coronal third; h: middle third; i: apical third)

DISCUSSION

The protocol of this study was designed to evaluate the residual filling material after retreatment of samples obturated with a new bioceramic endodontic sealer and Gutta percha. In an effort to minimize the number of variables in the study, only canines with similar dimensions were used and all groups followed the same instrumentation and irrigation protocol. A file two sizes greater than the initial master apical file was utilized for apical re-enlargement in an effort to efficiently decrease the material remnants.[19] The use of solvent during retreatment was avoided, as it may create a thin layer of filling debris on the dentinal walls that is difficult to eliminate.[20]

The bioceramic material remnants have been evaluated with various techniques such as digital radiography,[11] confocal microscopy,[15] microcomputed tomography,[6,12,17,18] optical microscopy,[7,14,16] and SEM.[10,13,15] The latter is the only method that can evaluate the cleanliness of the dentinal tubules.[13] Moreover, EDS is a method used to chemically characterize the filling debris.[21] Therefore, in this study, high-resolution SEM photomicrographs were used to observe the filling debris of retreated canals previously obturated with BioRoot RCS and Gutta percha.

The retreatment procedure was considered complete when the last instrument reached the WL and no filling debris could be observed on its surface.[12] Although the last instrument of the retreatment was a file two sizes greater than the initial master apical file, all root samples showed some remaining filling material during the SEM observation. Hence, the enlargement of the canal preparation or the lack of material debris in the files cannot guarantee the complete removal of the sealer from the root canal walls.

In this study, BiorOOT RCS exhibited the same amount of filling residues as the bioceramic TotalFill BC Sealer and the epoxy resin-based AH26. This comes in accordance with the study of Ersev et al., where they compared Endosequence BC Sealer to Hybrid Root SEAL and Activ GP and observed the same amount of filling debris after retreatment.[11] Similar results were demonstrated for iRoot SP versus MM Seal and AH Plus[13] and for Endosequence BC Sealer versus AH Plus.[11,15,18] On the other hand, other results indicate that the retreatment of iROOT SP[14] and Endosequence BC Sealer[6] left more filling remnants than AH26 and Pulp Canal Sealer EWT, respectively. Moreover, although the retreatment of BioROOT RCS resulted in similar amount of residues as Endo CPM Sealer, it exhibited less material leftovers than AH Plus.[7] The discrepancy of the results may be attributed to differences in methodology. For instance, while Donnermeyer et al. evaluated the sealer remnants with light microscopy,[7] this study used SEM images of higher magnification, which could possibly reveal more filling residues.

Moreover, some studies have employed Gates Glidden drills,[6,11,13,15] ultrasound tips,[16] and heat[10] for the removal of the coronal obturation material. Their additional use might affected the results and be responsible for the observation of more closed dentinal tubules[13] and more remaining filling material[11] in the apical third. On the contrary, in studies where the samples were instrumented only with rotary files, the percentage of the bioceramic sealer remnants on the apical third was similar[14] or less[17] from the middle and the coronal third. This study followed the latter instrumentation protocol and the intragroup comparison revealed the same amount of filling material in all canal thirds.

Research indicates that the WL can be reached in the majority of the specimens filled with Gutta percha and bioceramic sealer.[10,16,17] Furthermore, the percentage of apical patency recovery of canals obturated with bioceramic sealer and Gutta percha fluctuates from 80% to 100% in most studies.[10,15,16] Only one study did not confirm the former result and found a 14% patency attainment of canals filled with Endosequence BC sealer and Gutta percha.[17] The present research resulted in a 100% WL and patency recovery for all the samples, regardless of the bioceramic sealer used. These results indicate that WL and patency recovery are manageable in the clinical act.

CONCLUSION

A significant amount of material residues was found in the root canal. As a matter of fact both the bioceramic and the epoxy resin-based sealers left the same amount of filling remnants after retreatment. Moreover, the WL and patency reestablishment were achievable at all groups. Therefore, it can be concluded that the retreatability of the novel BioRoot RCS can be considered manageable in the clinical setting.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Trope M, Bunes A, Debelian G. Root filling materials and techniques: Bioceramics a new hope? Endod Top. 2015;32:86–96. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Haddad A, Che Ab Aziz ZA. Bioceramic-based root canal sealers: A review. Int J Biomater. 2016;2016:9753210. doi: 10.1155/2016/9753210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sarkar NK, Caicedo R, Ritwik P, Moiseyeva R, Kawashima I. Physicochemical basis of the biologic properties of mineral trioxide aggregate. J Endod. 2005;31:97–100. doi: 10.1097/01.don.0000133155.04468.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reyes-Carmona JF, Felippe MS, Felippe WT. The biomineralization ability of mineral trioxide aggregate and portland cement on dentin enhances the push-out strength. J Endod. 2010;36:286–91. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagas E, Uyanik MO, Eymirli A, Cehreli ZC, Vallittu PK, Lassila LV, et al. Dentin moisture conditions affect the adhesion of root canal sealers. J Endod. 2012;38:240–4. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2011.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Siqueira Zuolo A, Zuolo ML, da Silveira Bueno CE, Chu R, Cunha RS. Evaluation of the efficacy of TRUShape and reciproc file systems in the removal of root filling material: An ex vivo micro-computed tomographic study. J Endod. 2016;42:315–9. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donnermeyer D, Bunne C, Schäfer E, Dammaschke T. Retreatability of three calcium silicate-containing sealers and one epoxy resin-based root canal sealer with four different root canal instruments. Clin Oral Investig. 2018;22:811–7. doi: 10.1007/s00784-017-2156-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schirrmeister JF, Wrbas KT, Meyer KM, Altenburger MJ, Hellwig E. Efficacy of different rotary instruments for Gutta-Percha removal in root canal retreatment. J Endod. 2006;32:469–72. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2005.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ng YL, Mann V, Gulabivala K. A prospective study of the factors affecting outcomes of non-surgical root canal treatment: Part 2: Tooth survival. Int Endod J. 2011;44:610–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2011.01873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hess D, Solomon E, Spears R, He J. Retreatability of a bioceramic root canal sealing material. J Endod. 2011;37:1547–9. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2011.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ersev H, Yilmaz B, Dinçol ME, Dağlaroğlu R. The efficacy of ProTaper universal rotary retreatment instrumentation to remove single gutta-percha cones cemented with several endodontic sealers. Int Endod J. 2012;45:756–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2012.02032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma J, Al-Ashaw AJ, Shen Y, Gao Y, Yang Y, Zhang C, et al. Efficacy of ProTaper universal rotary retreatment system for gutta-percha removal from oval root canals: A micro-computed tomography study. J Endod. 2012;38:1516–20. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simsek N, Keles A, Ahmetoglu F, Ocak MS, Yologlu S. Comparison of different retreatment techniques and root canal sealers: A scanning electron microscopic study. Braz Oral Res. 2014;28:pii: S1806-83242014000100221. doi: 10.1590/1807-3107bor-2014.vol28.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uzunoglu E, Yilmaz Z, Sungur DD, Altundasar E. Retreatability of root canals obturated using gutta-percha with bioceramic, MTA and resin-based sealers. Iran Endod J. 2015;10:93–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim H, Kim E, Lee SJ, Shin SJ. Comparisons of the retreatment efficacy of calcium silicate and epoxy resin-based sealers and residual sealer in dentinal tubules. J Endod. 2015;41:2025–30. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2015.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agrafioti A, Koursoumis AD, Kontakiotis EG. Re-establishing apical patency after obturation with gutta-percha and two novel calcium silicate-based sealers. Eur J Dent. 2015;9:457–61. doi: 10.4103/1305-7456.172625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oltra E, Cox TC, LaCourse MR, Johnson JD, Paranjpe A. Retreatability of two endodontic sealers, EndoSequence BC sealer and AH plus: A micro-computed tomographic comparison. Restor Dent Endod. 2017;42:19–26. doi: 10.5395/rde.2017.42.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suk M, Bago I, Katić M, Šnjarić D, Munitić MŠ, Anić I, et al. The efficacy of photon-initiated photoacoustic streaming in the removal of calcium silicate-based filling remnants from the root canal after rotary retreatment. Lasers Med Sci. 2017;32:2055–62. doi: 10.1007/s10103-017-2325-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rödig T, Hausdörfer T, Konietschke F, Dullin C, Hahn W, Hülsmann M, et al. Efficacy of D-raCe and ProTaper universal retreatment NiTi instruments and hand files in removing gutta-percha from curved root canals – A micro-computed tomography study. Int Endod J. 2012;45:580–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2012.02014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schirrmeister JF, Wrbas KT, Schneider FH, Altenburger MJ, Hellwig E. Effectiveness of a hand file and three nickel-titanium rotary instruments for removing gutta-percha in curved root canals during retreatment. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:542–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murrieta-Pazos I, Galet L, Rolland C, Scher J, Gaiani C. Interest of energy dispersive X-ray microanalysis to characterize the surface composition of milk powder particles. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2013;111:242–51. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2013.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]