Abstract

Aim of the Study:

Bacteria that persist at the time of obturation increase the possibility of persistent apical periodontitis. An ideal sealer should be able to kill these remaining bacteria that are present on the dentinal walls as well as inside the dentinal tubules. This could be possible if a sealer has antimicrobial properties with optimum flow characteristics. Hence, the aim of this in vitro study was to assess the antimicrobial efficacy of epoxy resin-based sealer: AH Plus and Perma Evolution against Enterococcus faecalis on the 1st, 3rd, 5th, and 7th day and also to compare the flow characteristics of both epoxy resin-based sealers.

Materials and Methods:

E. faecalis ATCC 35550 strain was used to assess the antibacterial efficacy of sealers by agar-diffusion test (ADT) and direct-contact test (DCT). Flow characteristics of sealers were measured according to the ADA specification no. 57.

Results:

In ADT, Perma Evolution sealer showed larger zone of inhibition than AH plus on the 1st, 3rd, 5th, and 7th day, and in DCT, both sealers were equally effective in inhibiting E. faecalis growth on the 1st, 3rd, 5th, and 7th day. Flow test showed no significant difference between Perma Evolution and AH Plus sealer.

Conclusion:

Both the tested sealers were equally effective against E. faecalis up to 7 days of incubation period. Considering flow properties, both the tested sealers showed optimum flow as per the ADA specification no. 57.

Keywords: Enterococcus faecalis, microbiological analysis, sealers

INTRODUCTION

The ultimate goal of endodontic treatment is to eliminate microorganisms localized in root canal systems and to prevent reinfection by completely filling the canals with stable materials. However, current strategies can hardly achieve complete elimination of microorganism from the endodontic sites, leaving 40%–60% of the root canals still positive for bacterial presence.[1] The bacteria that survive in the root canals at the time of obturation have been shown to increase the possibility of posttreatment apical periodontitis.[2] These microorganisms infecting the root canal system might adhere superficially to the dentinal wall or may penetrate into the dentinal tubules or be present as biofilm (Ando and Hoshino 1990, Peters et al. 2001). Superficially, adhering bacteria are likely to be killed more easily than those present in biofilm or shielded in the depths of dentinal tubules.[2]

An ideal sealer should be able to kill the residual bacteria present on the dentinal walls of root canals along with those present deep inside the dentinal tubules. To achieve this, the sealer should not only kill the bacteria by contact action but also should be able to diffuse inside the dentinal tubules. This is possible only if the sealer has both antimicrobial properties and good flow properties.[3] However, not all sealers possess such properties, making the development of new materials with antimicrobial activity along with optimum flow characteristics desirable.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) which is defined as “the lowest concentration of antimicrobial agent that prevents the visible growth of a microorganism” is a method to assess the antimicrobial efficacy of material.[4] Agar dilution and broth dilution methods are the most commonly used methods to determine MIC of any antimicrobial agent. This is possible if the material is soluble in bacterial suspension during dilution. Resin-based sealers are insoluble material, and hence, it is difficult to determine MIC for these sealers by the above-mentioned method. Therefore, in such conditions, one has to rely on agar-diffusion test (ADT) and direct-contact test (DCT) to assess the antimicrobial effect of these materials.[5]

Enterococcus faecalis is one of the most frequently isolated species, recovered in over one-third of the canals of root-filled teeth with persisting periapical infection[1] and has been used as the test organism in this study.

In the present study, AH Plus sealer was used which is an established epoxy resin-based sealer, and as suggested by Kayaoglu et al., it provides provisional antibacterial effect against E. faecalis.[6] Perma Evolution is a newly introduced epoxy resin-based sealer in the market, and the manufacturer claims that this sealer has both antimicrobial properties along with optimum flow. However, the literature does not provide adequate data about the new epoxy resin-based sealer “Perma Evolution.”

Hence, the aim of this in vitro study was to assess the antimicrobial efficacy of AH Plus and Perma Evolution epoxy resin-based sealer against E. faecalis on the 1st, 3rd, 5th, and 7th day of growth and also to compare the flow characteristics of both epoxy resin-based sealers. The objectives of the study were as follows:

To assess the antimicrobial efficacy of AH Plus sealer against E. faecalis on the 1st, 3rd, 5th, and 7th day of growth

To assess the antimicrobial efficacy of Perma Evolution sealer against E. faecalis on the 1st, 3rd, 5th, and 7th day of growth

To compare the antimicrobial efficacy of AH Plus and Perma Evolution endodontic sealer against E. faecalis on the 1st, 3rd, 5th, and 7th day of growth

To assess and compare the flow characteristics of AH Plus and Perma Evolution.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

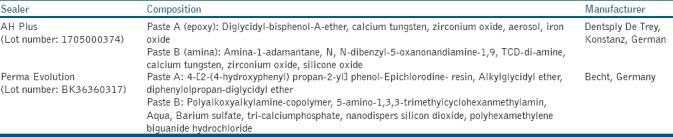

In this in vitro study, two epoxy resin-based sealers AH Plus and Perma Evolution [Table 1] were tested and compared for their antimicrobial activity against E. faecalis strain ATCC 35550, and flow characteristics of the sealer were also assessed.

Table 1.

Composition of sealers

Microbiological analysis

The antibacterial effect of sealers was tested with ADT and DCT against E. faecalis strain ATCC 35550. ATCC 35550 strain was used in this study which was provided by Skanda Life Sciences Pvt. Ltd., DSIR recognized R and D center, Bangalore. E. faecalis cell suspension was prepared from bacteria, grown on Tryptic soy broth for cultures. The cell suspensions of all the cultures were adjusted to 1–2 × 105 cells/ml.

Determination of antimicrobial activity by agar well-diffusion technique

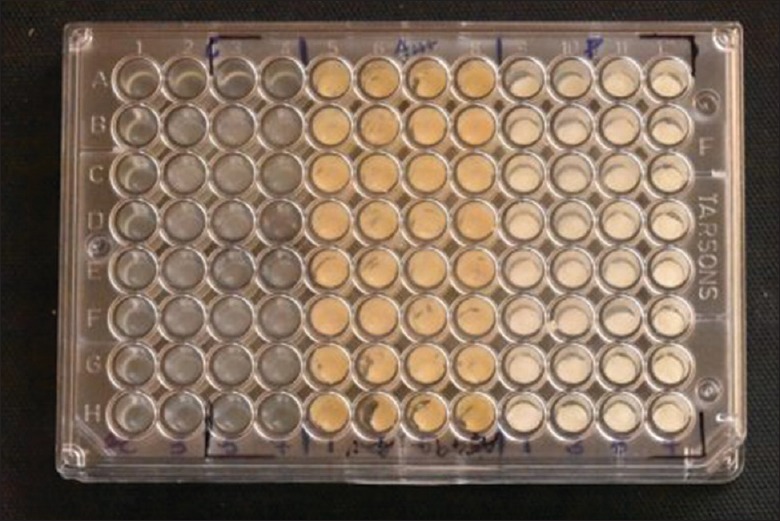

E. faecalis (100 μl) was inoculated on soyabean casein digested agar plates (90 mm) (HiMedia Laboratories, Mumbai, India) by spread plate technique. The test was done under strict aseptic conditions in a biological safety cabinet. The sealers were mixed by the manufacturer's recommendations. Briefly, 20 μl of each sealer was added into 5 mm × 4 mm wells on four agar plates, and phosphate buffer solution was used as control. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 7 days and observed for the zone of inhibition around the well on the 1st, 3rd, 5th, and 7th day as shown in Figure 1. The mean diameter of inhibition zones was measured in millimeters.

Figure 1.

Zone of inhibition on the 1st day

Determination of antimicrobial efficacy by direct-contact test

DCT based on turbidimetric determination of bacterial growth in 96-well microtiter plate was done in this study. Of the 96-well microtiter plate, four columns (32 wells) were utilized per se aler as well as for control group, then these four columns again were divided into the 1st, 3rd, 5th, and 7th day.

20 μl of each mixed sealer was added into the wells on microplate (n = 8/day). Then, 100 μL of E. faecalis (1–2 × 108 cells/ml.) inoculum was prepared in soyabean casein digested broth was added into each well. Soyabean casein digested broth without any sealer was added into well as a control group [Figure 2]. The plates were then incubated at 37°C for 7 days, and the growth of bacteria was measured in terms of optical density [OD] using spectrophotometrically at 600 nm in plate reader.

Figure 2.

Mixed sealer added into 96-well microtiter plate

Data were collected by recording OD, considering the fact that as bacterial population increases, the absorbance reading, i.e., OD given by spectrophotometer will also increase.

Flow test

Flow test of sealers was carried out by the ADA specification no. 57. Sealers were mixed according to the manufacturer's instruction, and then, 0.5 ml of this mixed sealer was dropped on the center of a glass slab and after 3 min, another glass slab (20 g) was placed on it with a cast iron weight (100 g) making total mass of 120 g.[3] The sealer spreads in a circular disc pattern. Ten minute after the initial mixing time, maximum and minimum diameter of the circular disc of sealer was measured in millimeter (mm) using digital calipers. For each sealer, the flow test was repeated five times.

Flow test was repeated if:[3]

The difference between maximum and minimum diameter was >1.0 mm

The circular pattern had nonuniform thickness, which was assessed visually.

Statistical analysis

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences for Windows (version 22.0) Released 2013. Armonk, New York, USA: IBM Corporation., was used to perform statistical analysis.

Descriptive statistics

Descriptive analysis includes expression of the zone of inhibition, flow, and OD in terms of mean and standard deviation.

Inferential statistics

One-way ANOVA test followed by Tukey's honestly significant difference post hoc analysis was used to compare the mean zone of inhibition (in mm) between three groups at different time intervals. Repeated measures of ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post hoc analysis were used to compare the mean zone of inhibition and OD between different time intervals in each study group. Independent Student's t-test was used to compare the mean flow (in mm) between two sealers. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Agar-diffusion test

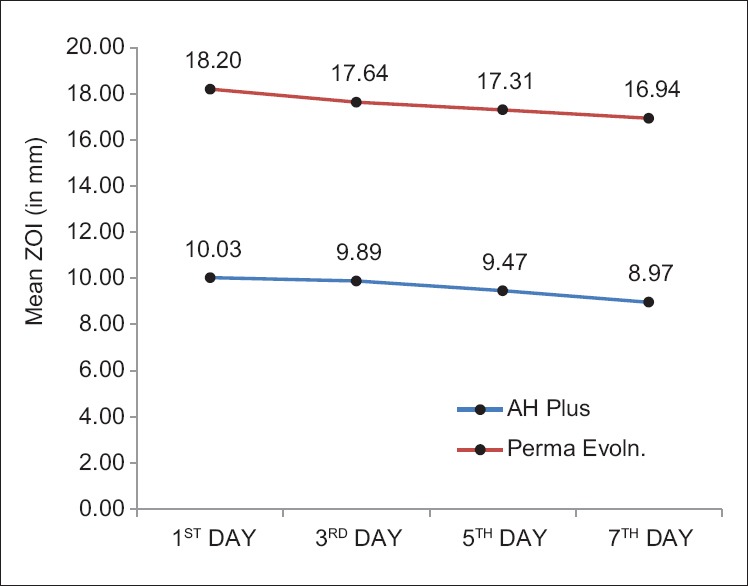

ADT showed significant difference in microbial inhibition among AH Plus and Perma Evolution. Zone of inhibition was largest in Perma Evolution (mean 18.20 ± 1.14) than AH plus (mean 10.03 ± 0.73) on the 1st, 3rd, 5th, and 7th day. Both sealers showed decreased zone of inhibition with time [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Comparison of mean zone of inhibition

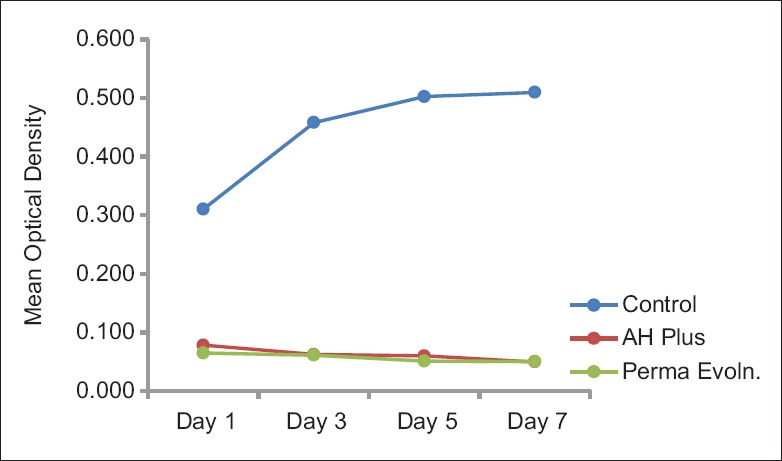

Direct-contact test

In DCT, both the sealers were effective in inhibiting E. faecalis growth on the 1st, 3rd, 5th, and 7th day as compared to the control group, and the statistical difference between AH Plus and Perma Evolution was not significant [Figure 4]. On calculation of percentage bacterial inhibition, both sealers showed up to 90% of bacterial growth inhibition on the 7th day.

Figure 4.

Growth curve ofEnterococcus faecalisin direct contact test

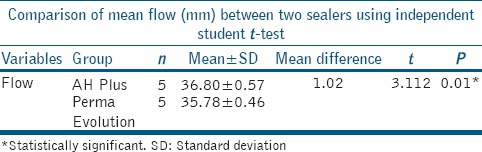

Flow test

Mean diameter of disc formed by AH Plus was 36.80 mm and 35.78 mm by Perma Evolution. AH Plus showed significantly better flow than Perma Evolution [Table 2].

Table 2.

Comparison of mean flow (mm) between two sealers

DISCUSSION

Good antimicrobial property and flow rate are the two most desirable properties of an ideal root canal sealer. The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the antimicrobial activity against E. faecalis and flow rate of two epoxy resin-based sealers – AH plus and the newly introduced Perma Evolution.

E. faecalis, a Gram-positive, facultative anaerobic microbes, was chosen in this study because it is the most common microorganism associated with posttreatment apical periodontitis and seems to be difficult to eradicate from the root canal system because of the several virulence factors of E. faecalis which help the organism to survive inside the root canal system, even after root canal therapy.[7] It has the ability to penetrate the dentinal tubules and adhere to collagen in the presence of human serum.[8] Evans et al. suggested that this may be due to microbe's ability to regulate internal pH and proton pump mechanism.[9] Apart from that, it can also bear prolonged starvation.[10] These findings may justify its use as a test organism in the present study.

The antibacterial activity of these sealers was measured by ADT and DCT. These are two most common tests to evaluate the antimicrobial activity of endodontic sealers.[11] However, the size of the inhibition zones formed in ADT does not indicate the absolute antimicrobial effect because the size of these inhibition zones may be affected by the solubility of the sealers.[12] This test is more suitable for water-soluble materials.[13]

On the other hand, in DCT, the antibacterial activity is independent of solubility and diffusibility of tested materials,[14] and in this test, bacteria are allowed to come in direct contact with the tested material.[15] Hence, DCT is more suitable to evaluate the antibacterial activity of insoluble materials or the material with very low solubility.[15]

In ADT, Perma Evolution showed larger zone of inhibition than AH Plus, this may suggest the better diffusivity of Perma Evolution than AH Plus. Both sealers showed decreased zone of inhibition with time, Smadi et al. suggested that it might be possible because generally in the set state, most constituents of the sealers are firmly bonded, and then, diffusion into the agar is difficult.[16]

However, in DCT, both sealers were effective in inhibiting the E. faecalis growth, and no statistically significant difference was found between the tested sealers, suggesting that DCT is independent of solubility of tested material and both tested sealers were able to maintain its antibacterial activity up to 7 days; however, Pizzo et al.[17] and Gong et al.[1] reported that AH Plus sealer has no inhibitory effect after 24 h, which is at variance with the present study.

One drawback of DCT is that this test uses the bacterial suspension, i.e., planktonic cells to assess the antibacterial effect of any material. There is evidence that microorganisms in the biofilms are up to 1000 times more resistant to antibacterial agents than the same bacteria in planktonic status.[18] Importantly, the current concept in endodontic microbiology considers endodontic disease as a biofilm-induced infection, emphasizing the importance of biofilm formation as an adaptive mechanism on-how bacteria survive in persisting endodontic infection.[19]

Antimicrobial effect of sealers depends on their chemical composition;[12] in AH Plus sealer, unpolymerized residues (i.e., epoxide and amine) may be released into the surrounding milieu during the setting process, resulting in provisional antibacterial activity, as suggested by Kayaoglu et al.,[6] and according to the manufacturer, Perma Evolution shows antimicrobial activity because of polyhexamethylene biguanide hydrochloride in its composition.

Size of a particle plays a vital role in flow characteristics of a sealer, and it is inversely proportional to flow.[20] If the sealer flow is less, then it will not be able to fill the irregularities and ramifications within the root canal system, and in between core material and root canal wall, on the other hand, higher flow of sealers might lead to its extrusion from the apical foramina. Hence, the optimum flow of sealer is desirable for the success of root canal treatment.[20] As per the ADA specification no. 57, the minimum flow of a root canal sealer should be ≥20 mm.[3] Both the tested sealers in this study exhibited the flow characteristics above this value and hence fulfilled the ADA criteria regarding the flow characteristics of sealers.

CONCLUSION

Within the limitations of this in vitro study, both the tested sealers were equally effective against E. faecalis up to 7 days of incubation period. DCT is a more suitable to assess the antimicrobial effect of endodontic sealer as it is independent of physical properties of material. Considering flow properties, both the tested sealers showed optimum flow as per the ADA specification no. 57.

Future directions

This in vitro study was carried out on the ATCC 35550 strain of E. faecalis (planktonic form), so the study on patients' strains (sessile form) in biofilm form is further required to validate our results. The maximum incubation period in this study was 7 days; long-term antimicrobial effect of these sealers has to be evaluated.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gong SQ, Huang ZB, Shi W, Ma B, Tay FR, Zhou B, et al. In vitro evaluation of antibacterial effect of AH plus incorporated with quaternary ammonium epoxy silicate against Enterococcus faecalis. J Endod. 2014;40:1611–5. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2014.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nawal RR, Parande M, Sehgal R, Naik A, Rao NR. A comparative evaluation of antimicrobial efficacy and flow properties for Epiphany, Guttaflow and AH-plus sealer. Int Endod J. 2011;44:307–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2010.01829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shakya VK, Gupta P, Tikku AP, Pathak AK, Chandra A, Yadav RK, et al. An in vitro evaluation of antimicrobial efficacy and flow characteristics for AH plus, MTA fillapex, CRCS and Gutta flow 2 root canal sealer. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:ZC104. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/20885.8351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiegand I, Hilpert K, Hancock RE. Agar and broth dilution methods to determine the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of antimicrobial substances. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:163. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heyder M, Kranz S, Völpel A, Pfister W, Watts DC, Jandt KD, et al. Antibacterial effect of different root canal sealers on three bacterial species. Dent Mater. 2013;29:542–9. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2013.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kayaoglu G, Erten H, Alaçam T, Ørstavik D. Short-term antibacterial activity of root canal sealers towards Enterococcus faecalis. Int Endod J. 2005;38:483–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2005.00981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kayaoglu G, Ørstavik D. Virulence factors of Enterococcus faecalis: Relationship to endodontic disease. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2004;15:308–20. doi: 10.1177/154411130401500506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Love RM. Enterococcus faecalis – A mechanism for its role in endodontic failure. Int Endod J. 2001;34:399–405. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.2001.00437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evans M, Davies JK, Sundqvist G, Figdor D. Mechanisms involved in the resistance of Enterococcus faecalis to calcium hydroxide. Int Endod J. 2002;35:221–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.2002.00504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Figdor D, Davies JK, Sundqvist G. Starvation survival, growth and recovery of Enterococcus faecalis in human serum. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2003;18:234–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-302x.2003.00072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kapralos V, Koutroulis A, Ørstavik D, Sunde PT, Rukke HV. Antibacterial activity of endodontic sealers against planktonic bacteria and bacteria in biofilms. J Endod. 2018;44:149–54. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2017.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gjorgievska E, Apostolska S, Dimkov A, Nicholson JW, Kaftandzieva A. Incorporation of antimicrobial agents can be used to enhance the antibacterial effect of endodontic sealers. Dent Mater. 2013;29:e29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mickel AK, Nguyen TH, Chogle S. Antimicrobial activity of endodontic sealers on Enterococcus faecalis. J Endod. 2003;29:257–8. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200304000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Slutzky-Goldberg I, Slutzky H, Solomonov M, Moshonov J, Weiss EI, Matalon S, et al. Antibacterial properties of four endodontic sealers. J Endod. 2008;34:735–8. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kesler Shvero D, Abramovitz I, Zaltsman N, Perez Davidi M, Weiss EI, Beyth N, et al. Towards antibacterial endodontic sealers using quaternary ammonium nanoparticles. Int Endod J. 2013;46:747–54. doi: 10.1111/iej.12054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smadi L, Khraisat A, Al-Tarawneh SK, Mahafzah A, Salem A. In vitro evaluation of the antimicrobial activity of nine root canal sealers: Direct contact test. Odontostomatol Trop. 2008;31:11–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pizzo G, Giammanco GM, Cumbo E, Nicolosi G, Gallina G. In vitro antibacterial activity of endodontic sealers. J Dent. 2006;34:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Costerton JW, Lewandowski Z, DeBeer D, Caldwell D, Korber D, James G, et al. Biofilms, the customized microniche. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2137–42. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.8.2137-2142.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Ahmad A, Ameen H, Pelz K, Karygianni L, Wittmer A, Anderson AC, et al. Antibiotic resistance and capacity for biofilm formation of different bacteria isolated from endodontic infections associated with root-filled teeth. J Endod. 2014;40:223–30. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2013.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernardes RA, de Amorim Campelo A, Junior DS, Pereira LO, Duarte MA, Moraes IG, et al. Evaluation of the flow rate of 3 endodontic sealers: Sealer 26, AH plus, and MTA obtura. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;109:e47–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]