Abstract

Background:

To assess clinical outcomes based on established rating scales in patients who underwent treatment for rhytids using laser resurfacing with and without facial plastic surgery.

Methods:

Retrospective case review of 48 patients treated by the senior author (J.E.B) between 2009 and 2016. Three reviewers assigned ratings to a total of 48 patients using estimated age and Fitzpatrick, Modified Fitzpatrick, and Glogau scales. Reviewers were blinded to patient demographics and before and after photographs. Patients elected to receive laser-only treatment or combination laser plus facial plastic surgery. Participants included forty-eight patients were selected on the basis that they had either laser treatment alone or laser plus facial plastic surgery and pre- and postoperative photographs.

Results:

Patients with higher Fitzpatrick scores had a greater reduction in Glogau score (ß = 1.66; SE = 0.59; P < 0.01). With respect to modified Fitzpatrick scores after surgery, patients with higher Glogau scores of 3 or 4 before surgery (P < 0.01) had higher scores after surgery ((ß = 0.07; SE = 0.02; P < 0.01). For estimated age, the average change was -1.7 years after laser resurfacing (P = 0.038; 95% CI, 2.96–3.06 years) and -2.07 years when combined with surgery (P = 0.01; 95% CI, 2.89–3.19 years).

Conclusions:

Patients with Fitzpatrick scores of 3, 4, 5, younger patients, and those with less rhytids before surgery tended to have lower Glogau scores after surgery. These findings provide insight on an approach to treating ethnic skin and aging face concerns.

INTRODUCTION

Within the realm of facial rejuvenation, more treatment options are being offered to patients now than ever before. Since the introduction of lasers for dermatologic treatment in the mid-1990s, advancements have been made to offer patients efficacious treatment with rapid healing time and minimal risk. Like any new procedure that has potential to cause harm, questions of laser safety and their short- and long-term effects have been investigated.1 Nevertheless, many agree that lasers are safe to use, and few complications arise when they are used by properly trained physicians.2 Senior author J.E.B. employs laser treatment in his practice for patients who seek reduction in rhytids among a variety of other modalities (eg, fillers and surgical facial rejuvenation procedures). Although such nonsurgical therapies offer a multitude of benefits for patients, there are limits to their application, and ultimately some patients will require facial plastic surgery to achieve their goals.

With ablative and nonablative laser resurfacing rising in popularity and becoming more accessible, surgeons have considered whether it is appropriate to use this augmenting technique pre, post, or perioperatively to achieve the greatest benefit with the highest safety profile.3,4 However, there is a paucity in studies that compare outcomes of laser treatment alone to laser treatment perioperatively with facial plastic surgery. The senior author aims to deliver the most comprehensive treatment to patients, and, as such, has taken steps to combine laser and facial plastic surgery safely and with efficacy in his practice. In this article, we aim to investigate outcomes of patients who have undergone either laser treatment and those who have had facial plastic surgery with laser perioperatively using estimated age, Glogau, Fitzpatrick, and Modified Fitzpatrick Scales.

METHODS

A retrospective review of 48 patients chosen based on the availability of preoperative and postoperative photographs and their consent to participate were included in this study. Patients were treated at 2 locations during 2 periods of time. The first cohort of 32 patients were treated at the Facial Plastics Surgery Division in the Department of Otolaryngology at San Antonio Military Medical Center from July 2009 to 2014, and then a second cohort of 16 patients were treated at a private practice clinic, Texas Facial Plastic Surgery and ENT, between 2015 and 2016. Photographs were taken in neutral expression before and after surgery in frontal and profile views of the face. All photographs were taken at the same level of chin elevation and zoom. Preoperative photographs were taken on average of approximately 1 month preoperatively ranging from 2 to 180 days. Postoperative photographs were taken on average 3 months postoperatively ranging from 10 to 150 days.

All patient’s medical records were thoroughly reviewed for information such as history of facial plastic surgery, resurfacing, or any supplementary procedures. Patient information such as age, surgeries performed, and laser settings are shown in Tables 1, 2. Institutional review board approval was obtained at San Antonio Military Medical Center before reviewing patient data.

Table 1.

Comparative Patient Demographics in the First Cohort

Table 2.

Comparative Patient Demographics in the Second Cohort

The senior author (J.E.B.) performs deep plane rhytidectomy by deep plane technique as described by Sykes et al.5 All surgeries were performed before laser treatment. Patients who received dermal filler placement were injected immediately after the laser resurfacing. Dermal filler placement was performed in both patient groups using a standard threading technique in select patients per patient preference. Restylane (Galderma, Fort Worth, Tex.) and Juvederm (Allergan, Irvine, Calif.) were injected into the mid to deep dermis. Radiesse (Merz, Raleigh, N.C.) was injected into the immediate subdermis. Anesthesia for the procedures included local, conscious sedation, and general anesthesia pending patient and surgeon preference.

Three laser platforms were used for the treatment of rhytidosis. The ablative, Lumenis Ultrapulse Fractional CO2 laser (Lumenis, San Jose, Calif.) was used for operations between 2009 and 2014, and the ablative Syneron-Candela CO2RE laser (Syneron-Candela, Wayland, Mass.) and nonablative Lumenis M22 Erbium Glass Resurfx (Lumenis, San Jose, Calif.) were used for operations between 2015 and 2016. The nonablative Lumenis M22 was used for patients with Fitzpatrick scores of 3–5, whereas the Ultrapulse and CO2RE lasers were used for patients with scores 1–3.

All patients were treated prophylactically with valacyclovir (500 mg, twice a day for 7 days), and the face was cleansed with acetone or mild soap preoperatively. All treatments used the hexagonal shape size 3. Laser settings are referenced in Tables 1, 2. The skin was cleaned at the conclusion of the procedure with normal saline. Patients were instructed to remain hydrated, apply aquaphor moisturizer for 3 days followed by an over-the-counter topical moisturizer, standard wound care, and daily broadspectrum sun screen with at least a 30+ sun protection factor (SPF) for rating for the following month.

Three reviewers agreed to evaluate patients for this study. The first cohort was rated by a dermatologist and facial plastic surgeon, and the second cohort was rated by an independent dermatologist. The measures for evaluation included estimated patient age and 3 objective wrinkle scales—Fitzpatrick, Glogau, and modified Fitzpatrick. Preoperative and postoperative digital photographs of both treatment groups were combined in random fashion for raters to review. In addition, preoperative images were randomized with postoperative images. The review method has been previously validated by Fitzpatrick et al.2 Raters were instructed to assign values from each scale to each set of frontal and profile photographs, and to estimate patient age, based on their experience.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS AND METHODOLOGY

Accounting for patient and surgeon bias is paramount in the critical analysis of facial plastic surgery outcomes. The data obtained from this study present methodological challenges that we must account for in our choice of inferential technique. First, there may be systematic rater biases (eg, based on professional experience and training) that should be tested and accounted for. Second, the rater data is both ordinal and categorical.

Considering that we must account for both patient characteristics and rater idiosyncrasy, regression is a natural choice for a statistical technique. As the data are ordinal and categorical, the best choice of statistical model is the cumulative link model proposed by McCullagh6 and implemented in the R package ordinal.7 A P value < 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

We are interested in how the senior author’s approach to treatment using various modalities affects patient outcomes suggested by Glogau and Modified Fitzpatrick ratings after the procedure, so these ratings are our (observed) response variables. Possible factors affecting these responses are Glogau, Fitzpatrick, Modified Fitzpatrick, and estimated age before treatment, and rater idiosyncrasy.

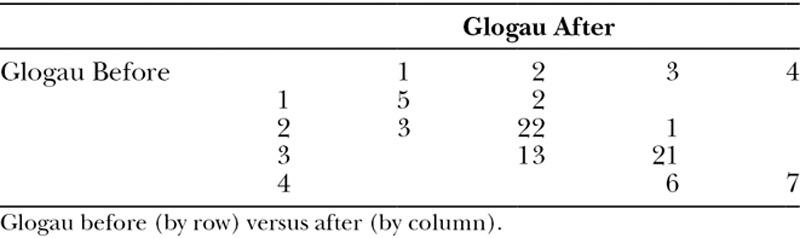

Table 3 is a contingency table of the Glogau ratings before and after procedures. There is a reasonably good dispersion of ratings, but for before values of 1 and 4, there are not many samples. Further, most of the before and after interactions are along the table diagonally. This means most patients either stay the same or change by one value. Some identification issues arose when fitting models including both Glogau and Fitzpatrick ratings before surgery. For some of the extreme categorical values, there simply were not enough cases. To alleviate the issue, aggregated scales containing 2 values were created. For Glogau before surgery, the aggregated scale binned patients into a group for all 1s and 2s and another for all 3s and 4s. For Fitzpatrick before surgery, the aggregated scale binned patients into a group for all 1s and 2s, and another for all 3s, 4s, and 5s. We also included dummy variables to account for individual rater idiosyncrasy. Reviewers 1 and 2 are now Rater A, and Reviewer 3 is now Rater B. Estimation of the final model is reported in Table 4. Table 5 details inter-rater and intra-rater estimates of age for patients undergoing laser resurfacing alone (L) and laser resurfacing with facial plastic surgery (LF).

Table 3.

Contingency Table

Table 4.

Modified Fitzpatrick, Glogua, and Estimated Age After Are Displayed

Table 5.

Estimated Age

RESULTS

Patient Demographics

Two groups consisting of 48 total patients were included in this study. Two treatment cohorts consisting of 31 patients who underwent both laser and facial plastic surgery and 17 patients who received laser-only treatment were blindly evaluated by 2 dermatologists (reviewers 1 and 3) and 1 facial plastic surgeon (reviewer 2). Four of these patients were treated first with facial plastic surgery, with an average of 522 days (range from 92–1,174 days) between surgery and laser treatment. The remaining 27 were treated with CO2 laser in the perioperative setting. The laser-only group of 17 patients were treated with CO2 or Erbium Glass laser only. Depending on patient goals, presurgical assessment, and finances, the best course of treatment was mutually decided upon by the patient and surgeon (J.E.B).

Specific patient demographics, surgery type, laser treatments, and filler information for the patient groups are outlined in Tables 1, 2. There were no operative or postoperative complications noted in any of the patients. No revision surgery or treatments have been necessary. Figs. 1, 2 have illustrated pre- and postoperative photographs.

Fig. 1.

Laser-only treatment.

Fig. 2.

Laser and facial plastic surgery.

Estimated Age

To evaluate the differences in estimated age between treatment populations, we used data from patients who underwent laser-only treatment and those who underwent laser in combination with facial plastic surgery. This method of comparison is different from the other analyses of the article, which look at overall outcomes. The average age change was -1.7 years after laser resurfacing (P = 0.038; 95% CI, 2.96–3.06 years) and -2.07 years when combined with surgery (P = 0.01; 95% CI, 2.89–3.19 years).

Glogau Scale

Using Glogau scale as an estimate of wrinkles in patients showed that patients with less wrinkles and photoaging, as defined by lower Glogau score, before surgery tended to have more favorable outcomes. Individuals with darker complexion (Fitzpatrick 3, 4, and 5) had more favorable outcomes as determined by the Glogau score (ß = 1.66; SE = 0.59; P < 0.01). With respect to Glogau scores after surgery, patients with higher estimated ages before surgery had higher scores after surgery (P < 0.01), as did patients with higher Glogau scores of 3 or 4 before surgery (P < 0.01). Thus, older appearing patients and patients with more rhytids before surgery did not experience a decrease in rhytids after surgery. Additionally, the Glogau 3, 4 (before) effect on the Glogau score after the procedure is positive (1.61) and the P value is small (0.02), confirming our intuition that patients with higher Glogau ratings before surgery will tend to have higher Glogau ratings after surgery.

Modified Fitzpatrick Scale

As in the Glogau ratings, there were some identification issues with the Modified Fitzpatrick scores, so the same aggregation technique was employed. In the data set obtained using the Modified Fitzpatrick scale, there is evidence of consistency in intrarater evaluation for both treatments reaching significance (P = 0.06, Rater A, P < 0.01, Rater B). To determine whether this disagreement may be confounding the results, we ran 2 separate model estimations for Rater A’s ratings and Rater B’s ratings. Patients with higher estimated ages before surgery tended to have higher scores after surgery (ß = 0.07; SE = 0.02; P < 0.01), as did patients with higher Glogau scores of 3 or 4 before surgery (P < 0.01).

DISCUSSION

Fractional laser resurfacing has been shown to be effective in treating facial rhytids. In a study evaluating apparent age, Swanson found that CO2 laser resurfacing reduced apparent age by 2.5 years.8 In recent years, fractionated CO2 laser therapy has also been shown to significantly improve photoaging of the face, a reduction in rhytidosis, and overall cosmesis.2,9,10 In this article, in patients receiving laser treatment only, the average age change was -1.7 years (P = 0.038; 95% CI, 2.96–3.06). These results add to the current literature that laser treatment is an effective way to reduce estimated age in patients. In patients who underwent facial plastic surgery with laser treatment, results showed an average reduction of -2.07 years (P = 0.01; 95% CI, 2.89–3.19). These findings are significant because they offer support for combining treatment modalities in certain patients whose goal may be to reduce their apparent age among other aesthetic outcomes.

It is worth noting that the patients in this case series that benefitted the most from the combination therapy were those with darker pigmented skin and patients with a lower estimated age. The Fitzpatrick 3, 4, 5, and estimated age effects control for Glogau rating before surgery, so their effects isolate relative effectiveness of the procedures. Those with higher Fitzpatrick scores (3, 4, and 5) had a strong association with a greater reduction in Glogau score after surgery in comparison with patients with a Fitzpatrick score of 1 and 2 (P value of < 0.01). In effect, darker patients with more rhytids before surgery tended to look younger, have less photoaging, and less wrinkles after surgery. Additionally, as apparent age increases, there is a lesser reduction in the postsurgery Glogau score, demonstrating a greater benefit in combination therapy among young patients.

The reason that patients with darker complexion showed a greater improvement is unclear, but may be useful in appropriating a treatment plan with patients of differing ethnicities. The greater benefit to younger patients may have resulted from an unbalanced data set. Perhaps there was a larger ratio of older patients to younger patients who elected for more aggressive therapy (combination therapy). Whatever the explanation, we can see that patients young and old can benefit from a combined technique.

With respect to modified Fitzpatrick scores after surgery, patients with higher estimated ages before surgery tended to have higher scores after surgery (P < 0.01), as did patients with higher Glogau scores of 3 or 4 before surgery (P < 0.01). The results indicate that older patients and those with more rhytids had less than favorable outcomes as compared with younger patients and those with less rhytids. These findings reveal underlying difficulties in treating certain populations. The current treatment technology may have limits as to the aesthetic effects it can provide. As a result, those with more severe rhytids may require more aggressive treatment modalities.

In our limited experience, combining fractionated CO2 laser resurfacing with surgery did not result in any complications, consistent with previously published.11,12 We have seen that combination therapy is a safe treatment option that delivers quality aesthetic results with minimal downtime and operating expense. Patients enjoy having combination therapy because it is less expensive, less painful overall, and more convenient for them to recover from a single operation over staged treatments. Albeit not measured, improvements in self-esteem, confidence, and wellness are seen in patients who receive laser and facial plastic surgery. Facial plastic surgery may well be entering into a new treatment paradigm that maximizes treatment benefit with combination therapy.

CONCLUSIONS

The combination of facial plastic surgery with fractionated CO2 lasers is a valuable method in the treatment of rhytidosis. Improvements in estimated age can be seen with either laser resurfacing or combination therapy. Added benefit may be seen in patients with higher Fitzpatrick scores. We add our experience to the experience of other surgeons, to continue demonstrating that this procedure has repetitively been performed safely with excellent results improving wrinkles and facial esthetics.

Footnotes

Published online 2 October 2018.

Disclosure: Dr. Barrera is a Consultant and Grant Recipient from Spirox, LLC. The Article Processing Charge was paid for by a Department of Defense Research Grant.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bisson MA, Grover R, Grobbelaar AO. Long-term results of facial rejuvenation by carbon dioxide laser resurfacing using a quantitative method of assessment. Br J Plast Surg. 2002;55:652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fitzpatrick RE, Goldman MP, Satur NM, et al. Pulsed carbon dioxide laser resurfacing of photo-aged facial skin. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guyuron B, Michelow B, Schmelzer R, et al. Delayed healing of rhytidectomy flap resurfaced with CO2 laser. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;101:816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright EJ, Struck SK. Facelift combined with simultaneous fractional laser resurfacing: outcomes and complications. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2015;68:1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sykes JM, Liang J, Kim JE. Contemporary deep plane rhytidectomy. Facial Plast Surg. 2011;27:124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCullagh P. Regression models for ordinal data. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, 1980). Series B 42, 109. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christensen RHB. Analysis of ordinal data with cumulative link models - estimation with the R-package ordinal. June 2015:1.

- 8.Swanson E. Objective assessment of change in apparent age after facial rejuvenation surgery. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64:1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanke CW, Moy RL, Roenigk RK, et al. Current status of surgery in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013 Dec;69(6):972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katz B. Efficacy of a new fractional CO2 laser in the treatment of photodamage and acne scarring. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koch BB, Perkins SW. Simultaneous rhytidectomy and full-face carbon dioxide laser resurfacing: a case series and meta-analysis. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2002;4:227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petersen R, Connor MP, Lospinoso D, et al. Combination laser resurfacing with facial plastic surgery is superior to lasers alone. Am J Cosmet Surg. 2015:32:12. [Google Scholar]