Abstract

Background:

A computerized cognitive rehabilitation program can be used to treat patients with mild cognitive impairment or dementia. We developed a new computerized cognitive rehabilitation program (Bettercog) that contained various treatment programs for cognitive training for mild cognitive impairment or dementia. This study was conducted to compare the clinical efficacy of Bettercog and computer-assisted cognitive rehabilitation (COMCOG) that has had clinical efficacy previously proven in patients with mild cognitive impairment or dementia.

Methods:

Randomized, single-blind comparison pilot study of 20 elderly patients with cognitive decline—eight men and 12 women—with an average age of 74.3 years. Bettercog trains not only memory and attention but also orientation, calculation, executive function, language, comprehension, and spatiotemporal abilities. To retain subjects’ interest, pictures, animations, and game elements were introduced. The subjects were divided into COMCOG and Bettercog groups by random assignment and underwent 12 sessions of a computerized cognitive rehabilitation program for three weeks. In a separate space, an independent clinical psychologist conducted the Seoul Neuropsychological Screening Battery 2nd edition (SNSB-II), Korean Mini-Mental State Examination (K-MMSE), Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR), and the Korean version of the Modified Barthel Index (K-MBI) before and after treatment.

Results:

There was no significant difference between the two groups in baseline age, sex, illiteracy, years of education, and scores on the K-MMSE, CDR, SNSB-II, and K-MBI. In the posttreatment cognitive assessment, the K-MMSE scores of patients treated with Bettercog improved from 19.2 ± 3.9 to 21.3 ± 4.0 (P = .005). In the memory domain of the SNSB-II, the percentile score improved from 15.3 ± 24.5 to 24.2 ± 30.7 (P = .026). However, there was no statistically significant difference in the final K-MMSE, CDR, and SNSB-II scores between the two treatment groups. In both groups, K-MBI scores improved statistically significantly after treatment.

Conclusions:

Through this preliminary study, we verified that the newly developed computerized cognitive rehabilitation program is effective in improving cognitive function. However, 12 sessions are not enough to administer a variety of cognitive rehabilitation content to patients. It is, therefore, necessary to conduct a large-scale study using a computerized cognitive rehabilitation program that has various cognitive content.

Keywords: activities of daily living, cognitive dysfunction, computer-assisted cognitive rehabilitation, dementia, memory, rehabilitation

1. Introduction

A characteristic of dementia is that the prevalence rate increases in proportion to increases in age.[1] In terms of socioeconomic costs, it is important to maintain the independent activities of daily living of patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or early dementia. Treatment options for patients with MCI or early dementia can be divided into pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatments. It has been reported that the former helps improve cognitive function and activities of daily living in patients with dementia.[2] Nonpharmacologic treatments, such as cognitive training or rehabilitation, exercise programs, and occupational therapy, have also been reported to be effective in alleviating the symptoms of dementia.[3]

Computerized cognitive rehabilitation programs are an amalgamation of existing cognitive rehabilitation programs and IT technology, which means that cognitive rehabilitation is performed using a touchscreen or joystick on a PC. Among computerized cognitive rehabilitation programs, RehaCom reported improvement of cognitive function in patients with stroke.[4] It has been reported that patients with Alzheimer dementia who have been treated with computer-assisted cognitive rehabilitation (COMCOG; Maxmedica Inc, Seoul, Korea) have demonstrated improved memory.[5]

However, while existing products have used joysticks to increase usability, this can be problematic for elderly patients who are unfamiliar with such technology in actual clinical application. In addition, since a joystick is always required to operate the program, it is difficult for computerized cognitive rehabilitation to be widely used as personal treatment equipment. In terms of program software, some cognitive rehabilitation programs are limited in that they focus only on the memory and attention domains, which limit the training of other cognitive domains.

Therefore, researchers designed a new computerized cognitive rehabilitation program (Better Cognition: Bettercog, M3 solution, Daegu, Korea) using touchscreen-based interface so that it can be applied to personal computerized cognitive rehabilitation treatment equipment. In terms of software, this computerized cognitive rehabilitation program includes several cognitive areas, and we considered cultural factors by reviewing the literature and cognitive training methods. This is a preliminary study to examine the clinical effect of Bettercog.

2. Methods

2.1. Development of a new computerized cognitive rehabilitation program

The previous Korean version of a computerized cognitive rehabilitation program was designed to focus on memory and attention training. Therefore, there was a need for a new computerized cognitive rehabilitation program that could address other aspects of cognition in patients with MCI and dementia. Based on the existing literature, we developed a new computerized cognitive rehabilitation program using words, photos, and images appropriate to Korean culture. We selected about 400 words based on literatures and cognitive training tools.

The computerized cognitive program consisted of orientation (time, place, person), attention, memory, language, executive function, visuospatial function, calculation, and motor functions such as finger tapping training. Each area was designed with 3 levels: easy, intermediate, and difficult. In the difficult level, the program was designed to enable integrated cognitive training between the main cognitive domain and other cognitive domains. For example, in the difficult level of calculation, after letting the participants remember a list of items to buy, they had to find the items, and were then asked the sum of the prices of purchased items to train short-term memory, calculation, and executive function.

To interest patients with MCI and dementia in the newly developed computerized cognitive rehabilitation program, game elements such as animations, game characters, and rewards for responses to correct answers were added.

2.2. Inclusion criteria

This study included participants who had a diagnosis of MCI, Alzheimer dementia, or vascular dementia. Cognitive function was screened using the Korean Mini-Mental State Examination (K-MMSE) and Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR). The cut-off value for MCI on the K-MMSE was 24, and a CDR of 0.5.[6,7] The study was approved by the Chungbuk National University Hospital IRB (no: 2016-10-005). Only those who voluntarily agreed to the research agreement were included in the study. This study was conducted from August 1, 2017 to March 10, 2018. A total of 21 subjects were enrolled in the study.

2.3. Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria included: visual disturbance, moderate to severe hemineglect, senile cataract, hearing difficulty, moderate to severe aphasia, moderate to severe Parkinson disease, initiation of cognitive enhancing drugs within the past month, changes in cognitive enhancing drug regimen during the clinical study, and other musculoskeletal or neurologic diseases that would affect the ability to control the touchscreen. Subjects were excluded from the study if they wanted to stop participating in the study at any point.

2.4. Evaluation of cognitive function

A Korean version of the Western Aphasia Battery was used to identify aphasia before initiation of treatment. We performed a star cancellation test, line cancellation test, and line bisection test to identify unilateral neglect before initiation of treatment.

The Seoul Neuropsychological Screening Battery 2nd edition (SNSB-II), a comprehensive neurocognitive function test suited to Korean culture, was administered before and after treatment. The SNSB-II consists of the 5 domains of cognitive function: attention, language and related functions, visuospatial function, memory, and frontal/executive function. It provides a raw score, percentile data adjusted by age and duration of education, and T scores.[8]

2.5. Evaluation of activities of daily living

The Korean version of the modified Barthel Index (K-MBI) was administered before and after treatment to assess activities of daily living.[9] Evaluations were conducted by experienced language therapists, clinical psychologists, and occupational therapists. All patients were examined by the same person before and after treatment.

2.6. Randomization and masking

This study is a preliminary study, and based on previous studies, we aimed to recruit 10 subjects per group.[10] Block randomization method was used, and 1 block consisted of 10 persons. To randomize the subjects, random numbers were generated using Excel's RAND function by an independent person who was not involved in clinical evaluation or treatment. The assigned random number was placed in a concealed envelope and delivered to the occupational therapist who performed the computerized cognitive training. Cognitive rehabilitation was completed by the randomly assigned subjects on COMCOG or Bettercog, which was administered by the same occupational therapist. Only the occupational therapist knew which computerized cognitive rehabilitation program to use during treatment and did not tell the subjects what the name of the program was. Both groups also used the same PC so as not to be able to deduce which group the subjects were assigned to by the device. The clinical psychologist evaluated cognitive function and K-MBI in an independent space. The clinical investigator, the physician, and the clinical psychologist did not know about the allocation until the end of the clinical study.

Subjects received 12 computerized cognitive rehabilitation treatments over 3 weeks. One session of computerized cognitive rehabilitation was performed for 30 minutes. The occupational therapist used the appropriate items of each computerized cognitive rehabilitation program in accordance with the participants’ cognitive function.

2.7. Statistical analysis

The primary variables for assessing the effectiveness of computerized cognitive rehabilitation were cognitive function scores, K-MMSE, CDR, and the 5 cognitive domains of the SNSB-II. The secondary variable for determining the effectiveness of computerized cognitive rehabilitation therapy was the K-MBI score measuring the activities of daily living.

The independent T test was performed to compare the 2 groups regarding education level, language and related function, visuospatial function, and memory domain of the SNSB-II at initial visit. The Mann–Whitney U test was used when the equal variance was not assumed. The Mann–Whitney U test was performed to compare the 2 groups regarding age, K-MMSE, CDR, attention and frontal/executive function domain of the SNSB-II at initial visit. The paired T test was performed to compare the 2 groups regarding scores on the K-MMSE, CDR, 5 cognitive domains of the SNSB-II, and the K-MBI at initial and final visit. The analysis of the 5 domains of the SNSB-II was performed using the percentile data in the population group which was adjusted for age and education. Fisher exact test was performed to compare sex, illiteracy, and type of dementia in both groups at baseline.

When analyzing the detailed cognitive functions constituting the SNSB-II, we selected some cognitive function evaluation tools appropriate for illiterate subjects and with percentile data for age and education level in Korea. Finally, a digit span test, a short form of the Korean–Boston naming test (S-K-BNT), the Rey-Osterrieth complex figure test (RCFT), and Seoul verbal learning test-elderly's version were selected among the SNSB-II for further analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS statistics 24 (IBM, Armonk, NY) and all statistical significance levels were set at .05.

3. Results

After excluding one subject due to a viral disease that required isolation, 20 subjects participated in the study. The mean age of the subjects was 74.3 ± 8.4 years, the duration of education was 6.3 ± 6.5 years, the initial K-MMSE score was 17.9 ± 5.1, CDR was 1.2 ± 0.9, and K-MBI was 47.5 ± 19.6.

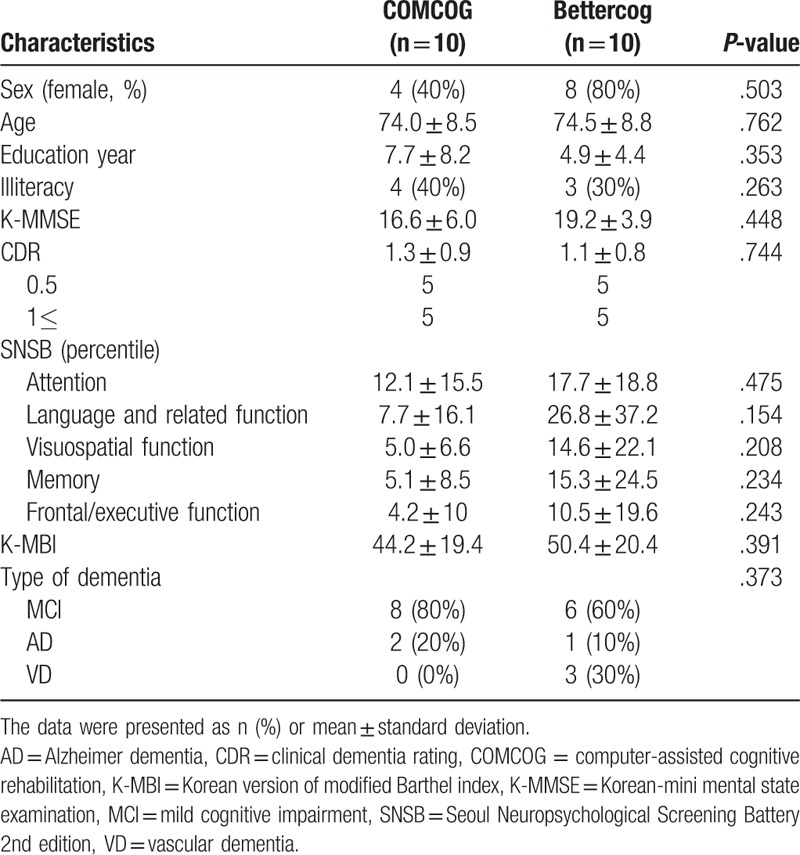

There were no statistically significant differences in age, sex, duration of education, literacy rate, and initial K-MMSE, CDR, SNSB-II, K-MBI scores, and type of dementia between the COMCOG and Bettercog groups (Table 1). Eight subjects in the COMCOG group and 9 in the Bettercog group completed the treatment sessions. There was no statistically significant difference in the number of treatments between the COMCOG (11.2 ± 1.9) and Bettercog (11.8 ± 0.7) (P = .474) groups.

Table 1.

Baseline general characteristics.

3.1. Changes in cognitive function

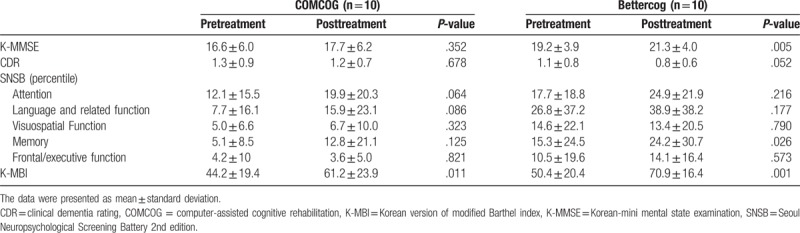

There was no statistical difference in K-MMSE, CDR, and SNSB-II scores between the COMCOG and Bettercog groups at initial and final examination. However, in the posttreatment cognitive function evaluation, it was found that the K-MMSE, CDR, and SNSB-II scores were improved before treatment. Especially, statistical significance was observed in the K-MMSE and the SNSB-II's memory domain in subjects treated with Bettercog (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison cognitive function and activity of daily living between pretreatment and posttreatment by treatment group.

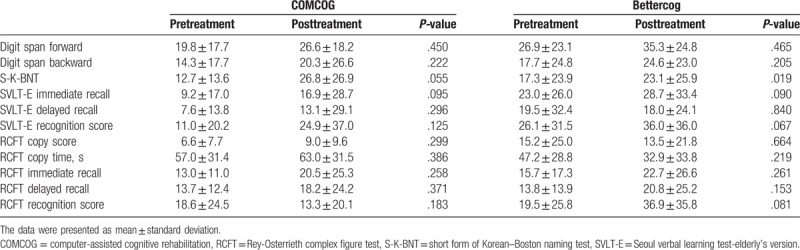

In further analyzing the constitutes of the SNSB-II, subjects who completed Bettercog and COMCOG had improvement in S-K-BNT score, but statistically significant observed in Bettercog group (Table 3).

Table 3.

Analysis of cognitive function test constituting Seoul Neuropsychological Screening Battery between pretreatment and posttreatment by treatment group.

3.2. Changes in abilities of activities of daily living

There was no statistical difference in K-MBI scores between the COMCOG and Bettercog groups at initial and final examination. The K-MBI score of subjects treated with COMCOG improved from 44.2 ± 19.4 to 61.2 ± 23.9 (P = .011), and the K-MBI score of those treated with Bettercog improved from 50.4 ± 20.4 to 70.9 ± 16.4 (P = .001).

4. Discussion

Cognitive rehabilitation therapy is a good treatment option for patients with MCI or dementia. Computerized cognitive rehabilitation is keeping pace with advances in IT technology, and clinical effectiveness has been verified in patients with various cognitive impairments such as multiple sclerosis and schizophrenia as well as dementia.[4,11,12]

The COMCOG, the 1st clinically licensed device in Korea, was selected for the control group for comparison with the new cognitive rehabilitation program in this study. Studies have reported that orientation, registration, and recall as assessed by the K-MMSE improved significantly in 35 Alzheimer dementia patients who underwent the therapy for 30 minutes daily over 4 weeks.[5] In another study, cognitive training using COMCOG consisting of 30 minutes sessions per day, 3 times a week over 4 weeks, was associated with improved performance on digit span tests, auditory controlled continuous performance tests, and finger tapping tests in patients with brain lesions.[10]

In this study, among the subjects treated with COMCOG, the scores on the K-MMSE, CDR, and 5 domains of the SNSB-II were improved but not statistically significant. While COMCOG confirmed the improvement of the digit span test after short-term cognitive training in previous studies, in this study, there was no effect on cognitive function, possibly because the treatment period of 3 weeks was insufficient to verify therapeutic effects.[10] Performance on the distal span test of the COMCOG was improved, similar to the results of a previous study, but it was estimated that the treatment period or recovery in the current study was insufficient as results did not reach statistical significance.

The K-MMSE score, memory domain of the SNSB-II, and S-K-BNT were statistically significantly improved in subjects who underwent computerized cognitive rehabilitation using Bettercog. This performance is better than the cognitive function performance in patients treated with COMCOG. However, considering the small number of participants in each group, shorter treatment periods than previous studies, and no definite difference in cognitive function between 2 groups before and after treatment, it is difficult to conclude that either treatment is superior.

The K-MBI results analyzed by the second outcome variables indicated that both groups’ performance improved over the course of treatment. This is consistent with previous studies that have indicated that computerized cognitive rehabilitation training has resulted in improvements in activities of daily living.[13]

This study has several important limitations in that there were few subjects and a short treatment period. As there were a limited number of treatment sessions, there were limitations on the variety of cognitive rehabilitation treatments that could be administered to patients. Another limitation to address is practice effects and the short test–retest interval. And the high illiteracy rate was a limitation in using cognitive assessment tools to evaluate language function and frontal/executive function. Results of visuospatial function and language and related functions of the SNSB-II after treatment using the Bettercog demonstrated that the Bettercog needs to improve in visuospatial function and language training software. Although SNSB, MMSE, and CDR were used to assess cognitive function, neurologists and psychiatrists did not participate in the differential diagnosis from other diseases that could cause cognitive decline. In addition, various types of dementia, MCI, Alzheimer disease, and vascular dementia were included as subjects; however, additional analysis of cognitive improvement in individual diseases was not performed due to the small number of subjects in each disease. In addition, there is a limit that the change of noncognitive symptoms accompanying dementia before and after treatment was not evaluated. This study is a preliminary study to evaluate the possibility of the therapeutic effect of newly developed computerized cognitive rehabilitation equipment. For Bettercog to be used in the treatment of MCI or mild dementia, large number clinical studies are needed to overcome the limitations.

5. Conclusion

Despite the limitations, cognitive function assessments such as the K-MMSE and memory domain of the SNSB-II demonstrated improvement after treatment using Bettercog and clinical results suggest that it may be a better therapeutic tool than COMCOG for cognitive function training for patients with early dementia or MCI.

Acknowledgment

The authors express their gratitude to Jae-woong Kim for his effort in collecting and organizing the literatures and articles and to Hye-young Gu, and Suwon Yoo for her efforts in the administrative process.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Heui Je Bang, Hyun Ho Kong.

Data curation: Goo Joo Lee, Miyeon Bang.

Investigation: Goo Joo Lee, Hyeun Suk Seo, Minwoo Oh, Miyeon Bang.

Methodology: Goo Joo Lee, Heui Je Bang, Kyoung Moo Lee, Hyun Ho Kong.

Project administration: Goo Joo Lee.

Supervision: Heui Je Bang.

Writing – original draft: Goo Joo Lee.

Writing – review & editing: Goo Joo Lee.

Goo Joo Lee orcid: 0000-0002-8436-4463.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: Bettercog = better cognition, CDR = clinical dementia rating, COMCOG = computer-assisted cognitive rehabilitation, K-MMSE = Korean mini-mental state examination, MCI = mild cognitive impairment, RCFT = Rey-Osterrieth complex figure test, S-K-BNT = short form of the Korean–Boston naming test, SNSB-II = Seoul Neuropsychological Screening Battery 2nd edition.

This work was supported by the Kyungpook National University IACT grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (1100-1141-305-024-17, Humancare Contents Development) and M3 solution (Daegu, Korea).

References

- [1].Prince M, Bryce R, Albanese E, et al. The global prevalence of dementia: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Alzheimers Dement 2013;9:63.e2–75.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Takeda A, Loveman E, Clegg A, et al. A systematic review of the clinical effectiveness of donepezil, rivastigmine and galantamine on cognition, quality of life and adverse events in Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2006;21:17–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Woods B, Aguirre E, Spector AE, et al. Cognitive stimulation to improve cognitive functioning in people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012. CD005562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Oh BH, Kim YK, Kim JH, et al. The effects of cognitive rehabilitation training on cognitive function of elderly dementia patients. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc 2003;42:514–9. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hwang JH, Cha HG, Cho YS, et al. The effects of computer-assisted cognitive rehabilitation on Alzheimer's dementia patients memories. J Phys Ther Sci 2015;27:2921–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lee KS, Cheong HK, Oh BH, et al. Comparison of the validity of screening tests for dementia and mild cognitive impairment of the elderly in a community: K-MMSE, MMSE-K, MMSE-KC, and K-HDS. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc 2009;48:61–9. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lim WS, Chong MS, Sahadevan S. Utility of the clinical dementia rating in Asian populations. Clin Med Res 2007;5:61–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kang YW, Na DL. Seoul Neuropsychological Screening Battery 2nd Edition (SNSB-II). Seoul: Human Brain Research & Consulting Co; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Jung HY, Park BK, Shin HS, et al. Development of the Korean Version of Modified Barthel Index (K-MBI): Multi-center Study for Subjects with Stroke. J Korean Acad Rehabil Med 2007;31:283–97. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kim YH, Jang EH, Lee SJ, et al. Development of computer-assisted memory rehabilitation programs for the treatment of memory dysfunction in patients with brain injury. J Korean Acad Rehabil Med 2003;27:667–74. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Campbell J, Langdon D, Cercignani M, et al. A randomised controlled trial of efficacy of cognitive rehabilitation in multiple sclerosis: a cognitive, behavioural, and MRI study. Neural Plast 2016;2016: 4292585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Dickinson D, Tenhula W, Morris S, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of computer-assisted cognitive remediation for schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2010;167:170–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Jeong W-M, Hwang Y-J, Youn JC. Effects of a computer-based cognitive rehabilitation therapy on mild dementia patients in a community. J Korean Gerontol Soc 2010;30:127–40. [Google Scholar]