Abstract

Young transgender women (YTW) are disproportionately affected by HIV, however, little is known about the factors associated with HIV infection and treatment engagement. We examined correlates of HIV infection and the steps of the HIV treatment cascade, specifically, being aware of their HIV infection, linked to care, on ART, and adherent to ART. We analyzed the baseline data of Project LifeSkills, a randomized control trial of sexually active YTW recruited from Chicago, Illinois and Boston, Massachusetts. We conducted multivariable Poisson regressions to evaluate correlates of HIV infection and the steps of the HIV treatment cascade. Nearly a quarter (24.7%) of YTW were HIV-infected. Among HIV-infected YTW, 86.2% were aware of their HIV status, 72.3% were linked to care, 56.9% were on ART, and 46.2% were adherent to ART. HIV-infected YTW who avoided healthcare due to cost in the past 12 months had lower odds of being linked to care (OR=0.55, 95% CI=0.30, 0.99) compared to those who did not, and HIV-infected YTW who do not have a primary care provider had lower odds of being on ART (OR=0.11, 95% CI=0.01, 0.74) compared to HIV-infected YTW who do. No YTW who did not have a primary care provider self-reported being adherent to ART. We observed suboptimal HIV treatment engagement among YTW. Our results suggest that improving linkage and retention in care by addressing financial barriers and improving access to primary care providers could significantly improve health outcomes of YTW as well as reduce forward transmission of HIV.

Keywords: HIV, young transgender women, HIV treatment cascade, access to care

INTRODUCTION

Transgender women, or women who identify along the transgender spectrum, are disproportionately affected by the HIV epidemic (Grant et al., 2016). A recent meta-analysis reported that 19.1% of transgender women worldwide are HIV-infected (Baral et al., 2013). While transgender women are estimated to have 48-times the odds of being infected with HIV compared to all adults (Baral et al., 2013), previous studies have reported low rates of HIV treatment engagement and poor health outcomes related to their HIV infection (Mizuno, Beer, Huang, & Frazier, 2017; Pitasi, Oraka, Clark, Town, & DiNenno, 2017; Santos et al., 2014; Wiewel, Torian, Merchant, Braunstein, & Shepard, 2016).

Systemic barriers commonly faced by young transgender women that potentiate HIV transmission rates and lead to suboptimal access to HIV and other health care include discrimination, stigma (White Hughto, Reisner, & Pachankis, 2015), violence (Operario, Soma, & Underhill, 2008), and the related structural challenges of securing housing, employment, health insurance and legal recognition (White Hughto et al., 2015), as well as high rates of condomless anal/vaginal sex (Baral et al., 2013), incarceration, substance use, depression and engaging in transactional sex (White Hughto et al., 2015).

More comprehensive information regarding YTW’s utilization of HIV prevention and treatment services is needed in order to identify gaps in care and to create targeted programs that encourage YTW to be more engaged in HIV prevention and treatment services. This study aims to fill this gap by examining demographic characteristics, risk behaviors, and health care access variables that are associated with HIV infection among YTW by using an adapted HIV treatment cascade.

METHODS

Participants (n=298) were recruited from Chicago, Illinois and Boston, Massachusetts for Project LifeSkills, a randomized controlled efficacy trial aimed at reducing HIV acquisition and transmission risk among YTW. Procedures have been described elsewhere previously (Kuhns, Mimiaga, Reisner, Biello, & Garofalo, 2017). In brief, participants were recruited using a combination of sampling strategies, including venue based sampling, study flyers, and snowball recruitment. Participants were eligible for Project LifeSkills if they were between the ages of 16 and 29, assigned male at birth and now identifies as a woman, female, or another identity on the transfeminine spectrum, spoke English, and self-reported engaging in risky sexual activity. Participants completed a two-hour baseline study visit that included a computer-assisted survey that collected information about their demographic characteristics, physical and mental health, sexual risk behavior, drug use history, and other risk behaviors. Participants were also asked to be tested for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections. All data collect, aside from the biological test results, were self-reported. All participants provided written informed consent, and the institutional review boards at both study sites approved of the study.

Young transgender women who self-reported being HIV uninfected but did not agree to a confirmatory HIV test or whose confirmatory HIV test results were missing/inconclusive were removed from this analysis set. The baseline data of the remaining 263 YTW were used for this cross-sectional analysis.

Variables included in this analysis were selected based on prior research (Baral et al., 2013; Reisner et al., 2017; Santos et al., 2014). We compared the demographic characteristics (e.g., race, age, education), risk behaviors (e.g., unprotected sex, sero-discordant sex, homelessness, injection drug use), and health care access (e.g., insurance status, has a primary care provider) of HIV-infected and uninfected YTW, as well as the demographic characteristics, risk behaviors, and health care access of HIV-infected YTW who knew their status, those who were linked to care, those who were prescribed ART, and those who were adherent to ART, compared to those who were not. All variables are listed in Table 1. Bivariate analyses of associations were conducted using χ2 tests. Poisson regressions were used model building. Predictors in the bivariate analyses with a p value <0.20 were included in separate multivariable analyses for each HIV-related outcome, and a stepwise backward elimination approach was used to fit the most parsimonious models, while controlling for race and income. All analyses were conducted in SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC).

Table 1.

Bivariate analyses: Correlates of HIV status among young transgender women in Chicago and Boston, 2012–2015.

| Total (n=263)* | HIV Negative (n=198)* | HIV Positive (n=65)* | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | <0.0001 | |||

| White | 59 (22.43) | 59 (29.80) | 0 (0.00) | |

| Black | 133 (50.57) | 87 (43.94) | 46 (70.77) | |

| Latina | 37 (14.07) | 30 (15.15) | 7 (10.77) | |

| Other | 34 (12.93) | 22( 11.11) | 12 (18.46) | |

| Recruitment City | <0.0001 | |||

| Boston | 119 (45.25) | 107 (54.04) | 12 (18.46) | |

| Chicago | 144 (54.75) | 91 (45.96) | 53 (81.54) | |

| Age (Mean, sd) | 23.41, 3.52 | 23.29, 3.51 | 23.78, 3.55 | 0.8938 |

| Education | 0.1721 | |||

| Less than high school | 64 (24.33) | 43 (21.72) | 21 (32.31) | |

| GED or high school diploma | 96 (36.50) | 72 (36.36) | 24 (36.92) | |

| Trade school or some college | 83 (31.56) | 65 (32.83) | 18 (27.69) | |

| Undergraduate degree or higher | 20 (7.60) | 18 (9.09) | 2 (3.08) | |

| Unemployed | 0.0933 | |||

| Yes | 198 (75.29) | 144 (72.73) | 54 (83.08) | |

| No | 65 (24.71) | 54 (27.27) | 11 (16.92) | |

| Household income | 0.0487 | |||

| Less than 10,000 | 120 (45.63) | 84 (42.42) | 36 (55.38) | |

| 10,000–19,999 | 34 (12.93) | 30 (15.15) | 4 (6.15) | |

| 20,000–39,999 | 26 (9.89) | 21 (10.61) | 5 (7.69) | |

| 40,000+ | 18 (6.84) | 17 (8.59) | 1 (1.54) | |

| Not sure | 65 (24.71) | 46 (23.23) | 19 (29.23) | |

| Living situation | 0.0338 | |||

| House/apartment that you own/rent | 99 (37.64) | 72 (36.36) | 27 (41.54) | |

| Parent/family’s house/apartment | 93 (35.36) | 79 (39.90) | 14 (21.54) | |

| Friend/partner’s house/apartment | 23 (8.75) | 14 (7.07) | 9 (13.85) | |

| Other | 48 (18.25) | 33 (16.67) | 15 (23.08) | |

| Ever homeless | 0.0570 | |||

| Yes | 139 (52.85) | 98 (49.49) | 41 (63.08) | |

| No | 124 (47.15) | 100 (50.51) | 24 (36.92) | |

| Homeless in the past 4 months | 0.2240 | |||

| Yes | 66 (25.10) | 46 (23.23) | 20 (30.77) | |

| No | 197 (74.90) | 152 (76.77) | 45 (69.23) | |

| Any unprotected sex in the past 4 months | 0.0054 | |||

| Yes | 156 (59.32) | 127 (64.14) | 29 (44.62) | |

| No | 107 (40.68) | 71( 35.86) | 36 (55.38) | |

| Any sero-discordant sex or sex with partners with unknown HIV status in the past 4 months |

<0.0001 | |||

| Yes | 106 (40.30) | 60 (30.30) | 46 (70.77) | |

| No | 157 (59.70) | 138 (69.70) | 19 (29.23) | |

| Ever engaged in transactional sex | 0.0238 | |||

| Yes | 138 (52.47) | 96 (48.48) | 42 (64.62) | |

| No | 125 (47.53) | 102 (51.52) | 23 (35.38) | |

| Ever injected drugs that were not prescribed | 0.5682 | |||

| Yes | 16 (6.08) | 13 (6.57) | 3 (4.62) | |

| No | 247 (93.92) | 185 (93.43) | 62 (95.38) | |

| Has insurance | 0.0694 | |||

| Yes | 189 (71.86) | 148 (74.75) | 41 (63.08) | |

| No | 74 (28.14) | 50 (25.25) | 24 (36.92) | |

| Has a primary care provider | 0.0682 | |||

| Yes | 187 (71.10) | 135 (68.18) | 52 (80.00) | |

| No | 76 (28.90) | 63 (31.82) | 13 (20.00) | |

| Avoided healthcare due to cost in the past 12 months | 0.2533 | |||

| Yes | 71 (27.00) | 57 (28.79) | 14 (21.54) | |

| No | 192 (73.00) | 141 (71.21) | 51 (78.46) | |

| Had any problems getting care because of gender identity/presentation | 0.0048 | |||

| Yes | 52 (19.77) | 47 (23.74) | 5 (7.69) | |

| No | 211 (80.23) | 151 (76.26) | 60 (92.31) | |

| Knew their status | 0.0011 | |||

| Yes | 248 (94.30) | 192 (96.97) | 56 (86.15) | |

| No | 15 (5.70) | 6 (3.03) | 9 (13.85) | |

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

Table 1 provides a detailed overview of the demographic and risk behavior characteristics of the sample population by HIV status. Our study sample’s demographic and risk behavior characteristics have been previously published (Reisner et al., 2016). The majority of YTW (94.3%) in the sample correctly knew their HIV status, about a quarter (24.7%) of the YTW were HIV-infected. Race, household income, living situation, any unprotected sex in the past 4 months, any sero-discordant sex in the past 4 months, history of transactional sex, and having trouble getting care because of gender identity were independently associated with HIV status.

HIV treatment cascade

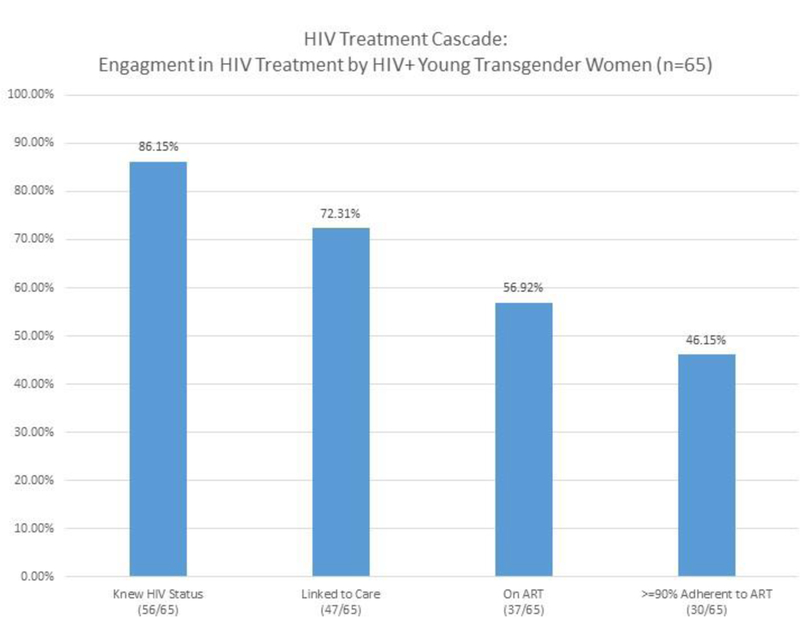

Of the HIV-infected YTW in our sample, 86.2% (56/65) knew that they were HIV-infected, 72.3% (47/65) were linked to care, 56.9% (37/65) were on ART, and 46.2% (30/65) were at least 90% adherent to ART.

Multivariable Poisson regression analyses of cascade steps

Table 2 presents sample characteristics stratified by each step of the HIV treatment cascade. HIV-infected YTW with a household income of $40,000+ had greater odds of knowing their status compared to HIV-infected YTW with a household income of less than $10,000 (aOR=1.13, 95% CI=1.00, 1.26).

Table 2.

Bivariable and multivariable Poisson regressions: Correlates of HIV treatment engagement among HIV+ young transgender women in Chicago and Boston, 2012–2015.

| Knew their HIV status | Linked to care | On ART | >=90% adherent to ART | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | |

| Race | ||||||||

| Black | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Latino | 0.99 (0.71, 1.36) | 0.94 (0.70, 1.27) | 1.19 (0.84, 1.70) | 1.10 (0.86, 1.40) | 1.26 (0.74, 2.15) | 1.17 (0.73, 1.87) | 1.64 (0.62, 4.38) | 1.59 (0.58, 4.37) |

| Other | 0.96 (0.73, 1.26) | 1.08 (0.88, 1.33) | 0.93 (0.60, 1.44) | 0.98 (0.66, 1.45) | 0.88 (0.48, 1.64) | 0.81 (0.36, 1.84) | 0.96 (0.36, 2.55) | 1.10 (0.35, 3.44) |

| Household income | ||||||||

| Less than 10,000 | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| 10,000–19,999 | 0.84 (0.47, 1.50) | 0.87 (0.53, 1.43) | 0.90 (0.50, 1.61) | 1.10 (0.68, 1.80) | 0.78 (0.28, 2.15) | 1.12 (0.22, 5.74) | 0.47 (0.06, 3.54) | 0.58 (0.06, 5.22) |

| 20,000–39,999 | 0.45 (0.15, 1.33) | 0.45 (0.16, 1.30) | 0.48 (0.16, 1.42) | 0.50 (0.18, 1.38) | 0.63 (0.21, 1.88) | 0.89 (0.37, 2.15) | 0.76 (0.18, 3.25) | 1.29 (0.29, 5.77) |

| 40,000+ | 1.13 (1.00, 1.26)* | 1.09 (0.93, 1.28) | 1.20 (1.04, 1.39)* | 1.12 (0.93, 1.35) | 1.57 (1.22, 2.00)* | 1.43 (1.06, 1.93)* | 1.89 (0.25, 14.15) | 1.93 (0.35, 14.89) |

| Not sure | 1.07 (0.91, 1.25) | 1.10 (0.93, 1.30) | 0.69 (0.46, 1.05) | 0.73 (0.50, 1.08) | 0.74 (0.43, 1.26) | 0.99 (0.61, 1.61) | 0.70 (0.29, 1.66) | 1.07 (0.43, 2.66) |

| Avoided healthcare due to cost in the past 12 months |

||||||||

| Yes | 0.79 (0.56, 1.12) | 0.78 (0.58, 1.06) | 0.53 (0.29, 0.99)* | 0.55 (0.30, 0.99)* | ||||

| No | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Has a primary care provider |

||||||||

| Yes | - | - | - | - | ||||

| No | 0.11 (0.02, 0.74)* | 0.11 (0.01, 0.74)* | ** | ** | ||||

p<0.05

Estimate and 95% CI were unable to be calculated due to complete separation of data. No YTW who did not have a primary care provider self-reported being adherent to ART.

In the final multivariable Poisson model, those who avoided healthcare due to cost in the past 12 months had lower odds of being linked to care compared to YTW who did not (aOR=0.55, 95% CI=0.30, 0.99).

Finally, those who did not have a primary care provider had lower odds of being on ART (aOR=0.11, 95% CI=0.01, 0.74) compared to those who did have a primary care provider. No YTW who did not have a primary care provider self-reported being adherent to ART.

DISCUSSION

Our findings show high prevalence of HIV among YTW in this sample; nearly a quarter of the sample reported living with HIV, which supports previous studies that show YTW highly impacted by and are at risk for HIV acquisition and transmission (Wilson et al., 2015; Garofalo et a., 2006). While YTW’s engagement along the HIV cascade is similar to the engagement observed among all HIV-infected individuals in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018), these findings underscore the gaps and areas for improvements in the care engagement.

In our final model, we found lower odds of being linked to HIV care among HIV-infected YTW who reported not seeing a doctor due to cost. Given the focus on broad access to health insurance for young people and the high priority placed on treatment for HIV in the United States, finding that cost remains a major barrier for linking HIV-infected YTW to care is concerning. Additionally, as majority of HIV-infected YTW in this sample display economic, it is vital for HIV care programs to facilitate linking this group both to care and financial options in efforts to address this barrier and increase linking to care.

Having primary care provider was found to represent an important determinant of utilizing and achieving adherence to HIV medication among HIV-infected YTW in this sample – such that those who did not have a primary care provider had significantly lower odds of being on and being highly adherent to ART. These findings are in line with other studies that link access to primary care provider with engagement and retention in HIV care (Khalili, Leung, & Diamant, 2015; Lurie, 2005; Sanchez, Sanchez, & Danoff, 2009). A qualitative study assessing engagement and retention in care among HIV-infected transgender found that receiving culturally competent transgender-sensitive health care was an important facilitator, empowering transgender women to be more involved in their healthcare. For example, a study by Reisner et al. (Reisner et al., 2015) highlighted the importance of gender affirming care, or care that is specific to YTW’s health needs, in engaging YTW in healthcare systems.

This study is not without limitations. The cross-sectional nature of this study does not allow us to examine the directionality of the associations. Additionally, the YTW in our study were recruited from two major metropolitan United States cities and were not randomly sampled, and may not be representative of the entire YTW population. Despite these limitations, the Project LifeSkills cohort is the largest cohort of YTW in the United States and the comprehensive questionnaire used in this study allowed us to gain insight into the lives of a disenfranchised population.

Young transgender women are at high risk for HIV and our study has demonstrated that engagement in HIV treatment is low. Specifically, our findings highlight the relationship between access to health care and better HIV treatment engagement. This includes having access to financial options to lower cost of care and to primary care providers proving HIV services, significantly predict better outcomes of the HIV treatment cascade for this group. While these associations have been described in the broader HIV literature, very little is known about how to improve access and treatment engagement among HIV-infected YTW. Further research is needed to identify points of intervention to increase HIV treatment engagement and what targeted public health messaging is most effective at reaching this population.

Figure 1.

HIV treatment cascade among HIV+ young transgender women in Chicago and Boston.

References

- Baral SD, Poteat T, Stromdahl S, Wirtz AL, Guadamuz TE, & Beyrer C (2013). Worldwide burden of HIV in transgender women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis, 13(3), 214–222. 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70315-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). Understanding the HIV Care Continuum Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/factsheets/cdc-hiv-care-continuum.pdf:

- Grant RM, Sevelius JM, Guanira JV, Aguilar JV, Chariyalertsak S, & Deutsch MB (2016). Transgender Women in Clinical Trials of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 72 Suppl 3, S226–229. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalili J, Leung LB, & Diamant AL (2015). Finding the perfect doctor: identifying lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender-competent physicians. Am J Public Health, 105(6), 1114–1119. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhns LM, Mimiaga MJ, Reisner SL, Biello K, & Garofalo R (2017). Project LifeSkills - a randomized controlled efficacy trial of a culturally tailored, empowerment-based, and group-delivered HIV prevention intervention for young transgender women: study protocol. Bmc Public Health, 17(1), 713 10.1186/s12889-017-4734-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lurie S (2005). Identifying Training Needs of Health-Care Providers Related to Treatment and Care of Transgendered Patients: A Qualitative Needs Assessment Conducted in New England. International Journal of Transgenderism, 8(2–3), 93–112. 10.1300/J485v08n02_09 [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno Y, Beer L, Huang P, & Frazier EL (2017). Factors Associated with Antiretroviral Therapy Adherence Among Transgender Women Receiving HIV Medical Care in the United States. LGBT Health, 4(3), 181–187. 10.1089/lgbt.2017.0003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Operario D, Soma T, & Underhill K (2008). Sex work and HIV status among transgender women: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 48(1), 97–103. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31816e3971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitasi MA, Oraka E, Clark H, Town M, & DiNenno EA (2017). HIV Testing Among Transgender Women and Men - 27 States and Guam, 2014–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 66(33), 883–887. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6633a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner SL, Biello KB, White Hughto JM, Kuhns L, Mayer KH, Garofalo R, & Mimiaga MJ (2016). Psychiatric Diagnoses and Comorbidities in a Diverse, Multicity Cohort of Young Transgender Women: Baseline Findings From Project LifeSkills. JAMA Pediatr, 170(5), 481–486. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.0067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner SL, Bradford J, Hopwood R, Gonzalez A, Makadon H, Todisco D, … Mayer K (2015). Comprehensive transgender healthcare: the gender affirming clinical and public health model of Fenway Health. J Urban Health, 92(3), 584–592. 10.1007/s11524-015-9947-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner SL, Jadwin-Cakmak L, White Hughto JM, Martinez M, Salomon L, & Harper GW (2017). Characterizing the HIV Prevention and Care Continua in a Sample of Transgender Youth in the U.S. AIDS Behav, 21(12), 3312–3327. 10.1007/s10461-017-1938-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez NF, Sanchez JP, & Danoff A (2009). Health care utilization, barriers to care, and hormone usage among male-to-female transgender persons in New York City. Am J Public Health, 99(4), 713–719. 10.2105/AJPH.2007.132035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos GM, Wilson EC, Rapues J, Macias O, Packer T, & Raymond HF (2014). HIV treatment cascade among transgender women in a San Francisco respondent driven sampling study. Sex Transm Infect, 90(5), 430–433. 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White Hughto JM, Reisner SL, & Pachankis JE (2015). Transgender stigma and health: A critical review of stigma determinants, mechanisms, and interventions. Soc Sci Med, 147, 222–231. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiewel EW, Torian LV, Merchant P, Braunstein SL, & Shepard CW (2016). HIV Diagnoses and Care Among Transgender Persons and Comparison With Men Who Have Sex With Men: New York City, 2006–2011. Am J Public Health, 106(3), 497–502. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]