Abstract

Microcystic, elongated, fragmented (MELF)-pattern is an unusual morphology of myometrial invasive front in endometrioid endometrial carcinoma (EA). The aim of the study was to investigate potential correlation between MELF-pattern and peritumoral inflammatory immune response. A total of 96 out of 368 patients were included in this study. CD3, CD20, CD57. CD68 and S100 markers were used for the detection of tumor-associated T-lymphocytes (TAT), tumor-associated B-lymphocytes (TAB), tumor-associated NK-lymphocytes (NK), tumor-associated macrophages and dendritic cells respectively. Mann-Whitney tests, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, and Spearman correlation were used as methods for statistical analyses. Odds ratio with 95% confidence interval (95% CI) was determined with the use of a logistic regression model. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Our results suggested that the number of CD3 and CD68 cells were significantly lower (p < 0.001) in cases of endometrioid carcinoma with MELF-pattern. A significant correlation between the presence of MELF-pattern and decrease of CD3 positive T-lymphocytes (r = 0.691; p < 0.001) was also observed. Additionally, we found an inverse correlation between the presence of MELF-pattern and TAM (r = 0.568; p = 0.001). Therefore, our data suggest that MELF-pattern may be associated with EA stroma fibrosis that contains immune cells infiltration and demonstrated a decrease in the number of TAT and TAM cells. This may indicate the poor clinical prognosis of this disease.

Keywords: Endometrioid endometrial carcinoma, MELF-pattern, Tumor immunoenvironment, Cancer stroma

Introduction

The term “MELF pattern” is used to describe an unusual morphology of a myometrium that is invaded by endometrial endometrioid adenocarcinomas (EA). Although most invasive EA have clear borders, glands of the tumors with the MELF pattern undergo morphologic changes that appear as microcystic, elongated, or fragmented, and are accompanied by fibromyxoid stromal reaction and intense inflammatory responses [1].

MELF-pattern is associated with lymphovascular invasion, lymph node metastasis and progression of EA [2–4]. Most studies focused on the fundamental and clinical role of cancer biomarkers. For example, Steward and Little (2009) reported that MELF-type invasion represented a specific tumor alteration, with a reduction in estrogen receptor and E-cadherin expression which is consistent with epithelial-mesenchymal transition [5]. Additionally, other studies reported roles for CXCL14-CXCR4 and CXCL12-CXCR4 axes and galectin-3 in invasiveness of MELF-pattern in EA [1, 6].

However, to our knowledge, there is no literature available reporting presence of immune cells in peritumoral infiltration in EA with/without MELF-pattern. It is now widely accepted that in all stages of neoplastic development, tumor cells coinhabit with various types of immune cells at densities ranging from subtle infiltration to gross inflammation. Though these immune cells were originally thought to be part of the antitumoral responses by the immune system to eradicate tumors, more evidences have pointed to the fact that the tumor-associated inflammatory response has a paradoxical effect of enhancing tumor initiation, progression and ultimately metastasis [7, 8].

In this study, we hypothesize that MELF-pattern could have reciprocal interactions with peritumoral inflammatory response. Therefore, we investigated presence of immune cells in tumor microenvironment using immunohistochemical technique, and reported for the first time that these criteria may be used as possible prognostic factors of the EA of corpus uteri.

Materials and Methods

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the Committees for Medical and Health Sciences of Research Ethics of Gomel State Medical University. Dispensation from the requirement of patient consent was granted.

Patient Characteristics

This prospective study involved women with endometrial EA who were treated in year 2015 in the Grodno region, Republic of Belarus. The inclusion criteria for the study were stage I-III (FIGO, 2009), the presence of EA, hysterectomy and the absence of malignant tumors of other localizations during life. The exclusion criteria for the study were as follows: IV stage (FIGO, 2009), Lynch syndrome, palliative treatment, presence of synchronous and metachronous malignances.

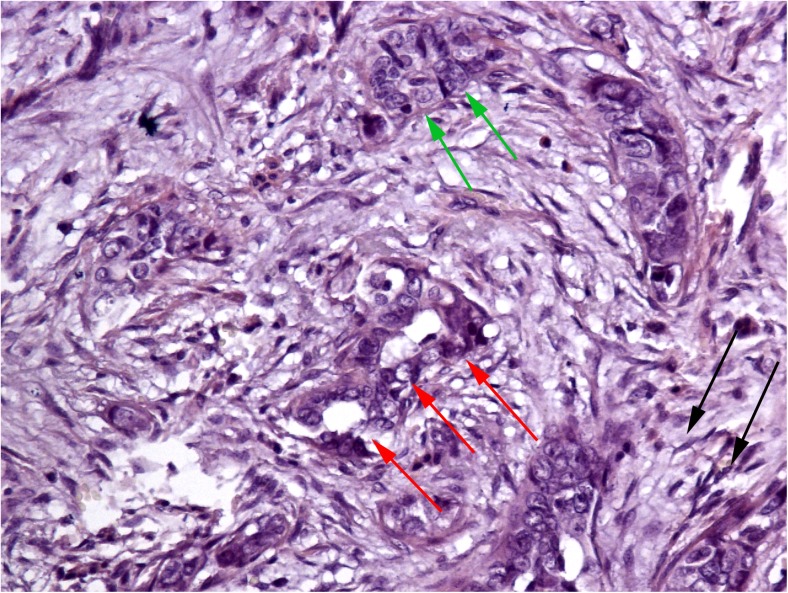

MELF-pattern areas were identified during routine haematoxylin and eosin-stained sections which were most prominent at the deepest myoinvasive aspect (invasive front) of the tumors. Criteria of MELF-pattern were the presence of elongated, dilated (‘microcystic’) and disrupted invasive neoplastic glands, that typically were lined wholly or in part by attenuated epithelial cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm. The glands sometimes showed a neutrophil polymorph infiltrate admixed with intraluminal epithelial cells. A characteristic feature was the presence of a peri-glandular fibromyxoid stromal reaction, and single invasive tumor cells were often seen within the stroma around the glands (Fig. 1). A total of 96 out of 368 cases of EA during the study period were determined to be eligible for inclusion in the study. Patients were divided into two groups according the presence or absence of MELF-pattern. The first group included 45 subjects who had EA with stroma-specific MELF-pattern (MELF positive group). The second group consisted of 51 patients who had no MELF-pattern changes in stroma (MELF negative group). Clinico-pathological characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

A MELF-pattern cancer stroma in area of tumor invasion with specific fibromyxoid changes (black arrows), eosinophilic cytoplasm microcystic glands (red arrows) and some areas resemble cancer vascular invasion (green arrows). Stain: Hematoxylin and eosin. Magnification: ×400

Table 1.

Clinico-pathological characteristics of the patients

| Characteristics | MELF-pattern positive group (n = 45) | MELF-pattern negative group (n = 51) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 65.3 ± 6.1 years | 63.3 ± 5.8 years | 0.583† |

| FIGO stage: | |||

| I | 10 | 11 | 0.947* |

| II | 22 | 25 | |

| III | 13 | 15 | |

| Tumor grade: | |||

| G1 | 19 | 22 | 0.864* |

| G2 | 21 | 22 | |

| G3 | 5 | 7 | |

| Radiation therapy: | |||

| Present | 17 | 22 | 0.679₰ |

| Abscent | 28 | 29 | |

| Postoperative chemotherapy: | |||

| Present | 25 | 25 | 0.546₰ |

| Abscent | 20 | 26 | |

| 5-year survival: | |||

| Death | 30 | 40 | 0.485₰ |

| Alive | 15 | 11 | |

† Mann-Whitney U test; * Kruskal-Wallis test; ₰ Two-tailed exact Fisher’s test

Immunohistochemistry

Primary antibodies used in this study include the following: ready-to-use monoclonal mouse anti-CD68 (TAM), anti-CD3 (TAT), anti-CD20 (TAB), anti-CD57 (NK), and ready-to-use polyclonal rabbit anti-S100 (DC) (Diagnostic Biosystems). UnoVue HRP/DAB Detection System (Diagnostic Biosystems) was used for primary antibodies visualization. These markers were chosen according to the recommendations of manual “Tumor Immunoenvironment” [9].

Sections of tissue on poly-L-lysine coated glass slides (4 to 5 μm thick) were deparaffinized and washed with distilled water for 3 min. Antigen retrieval was performed using antigen unmasking solutions Tris-EDTA buffer (1 mM, pH 9.0) and citrate buffer (1 mM, pH 6.0), with preheating in the microwave at 800 W for 5 min and at 600 W for 10 min, respectively. The sections were then allowed to cool in the same solution. Endogenous peroxidase blocking was done in 5% hydrogen peroxide for 20 min, and blocking of nonspecific antibody binding was ensured by incubating the sections in 5% casein in Tris-buffered solution for 1 h. After a brief wash in Tris-buffered solution, the sections were incubated in moist chamber at room temperature for 2 h with corresponding primary antibodies. Tissue sections were then incubated at room temperature for 30 min with anti-mouse HRP secondary antibodies. Between each step, the sections were washed twice with Tris-buffered solution for 5 min each. The reaction product was visualized with 3,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB) staining for 5 min, followed by Mayer’s hematoxylin counterstaining [10, 11].

Morphometry

Evaluation of antibody expression was produced in terms of percentage peritumoral positive immune cells per 100 cells in a high-power field (HPF) and the results are expressed as percentage positive cells. The tumor invasion zone was photographed using a microscope (Nikon Eclipse 50i) with digital camera (DS-Fi2) in 5 non-overlapping HPF of maximum expression for each marker. All measurements were carried out at ×400 magnification. Cell counting was analyzed using a image analysis software NIS-Elements Advanced Research (Nikon, Japan).

Statistical Analysis

The results of positive cells were compared between the group with MELF-pattern and in group without it. 3 cases were selected from each group, each of which was measured in 4 HPF, (12 HPF in each group). The obtained sample size, with a study power of 80% and α = 0.05, amounted to at least 88 HPF or measurement ranges for each comparison group. When calculating 4 HPF per object, the minimum number of subjects in one group was at least 22, and when calculating 5 HPF – for one object the minimum number of subjects was at least 18. All data were presented by the median, lower and upper quartiles. Mann-Whitney test was used for comparing the study groups based on the evaluated criteria. Receiver operator characteristics (ROC) analysis was used to compare the study groups according to the criteria and to find the threshold indicator. A Spearman correlation test was used to perform correlation analysis. Odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (95% CI) was determined with the use of a logistic regression model. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. IBM SPSS v23 and MedCalc Statistical Software v. 17.8.5 were used for analysis.

Results

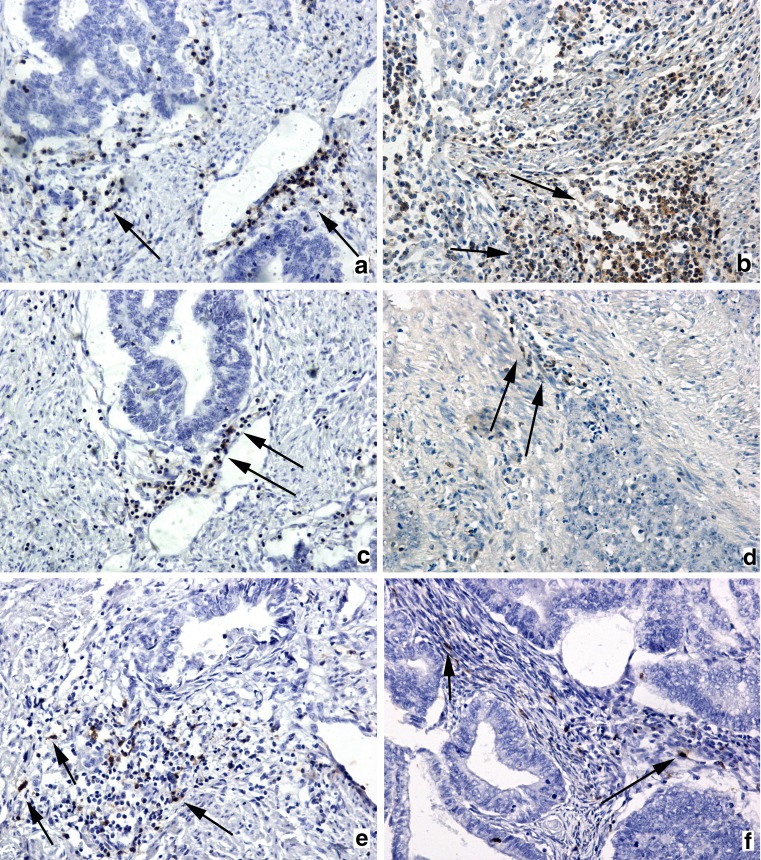

Tumor-Associated T-Lymphocytes

TATs in group of MELF-pattern positive patients were situated in weak infiltrates, mostly near carcinoma cells forming microcystic and elongated structures (Fig. 2a). TAT in cases without specific changes of tumor stroma has dense infiltrate within the cancer stroma and glands (Fig. 2b). In the group without changes of stroma TAT median was 27.4% (25.3%–36.9%) in MELF-positive group and 42.6% (36.9%–45.3%) in group without MELF pattern of stroma. Mann-Whitney test reveals statistically significant differences in CD3-cells expression in both groups (p < 0.001). On the basis of the ROC-analysis, a total CD3-positive cells threshold of 37.1% was adopted as the best differentiating value between patients who has MELF-pattern stroma changes and without it, with 75.0% specificity and 74.1% sensitivity (area under the curve was 0.75; p < 0.001).

Fig. 2.

Infiltration of lymphocytes in cancerous stroma. Immunochistocemistry for CD3: weak tumor-associated CD3+ T-lymphocytes infiltrate of MELF-changed stroma, presented as a small group of cells marked by arrows (a) and dense CD3+ tumor-associated T-lymphocytes infiltrate of invasion area in group without MELF-pattern (arrows) (b). Immunochistocemistry for CD20: weak infiltration by CD20+ tumor-associated B-lymphocytes infiltrate (arrows) of cancer stroma in groups with and without MELF-pattern (c-d). Immunochistocemistry for CD57: small groups of tumor-associated CD57+ NK-lymphocytes (arrows) infiltrate cancer stroma of endometrioid endometrial carcinoma group with MELF-pattern (e); weak tumor-associated CD57+ NK-lymphocytes (arrows) infiltrate situated between cancer glands in area of invasion in group without MELF-pattern (f). Magnification: ×100. Counterstain: Hematoxylin

Tumor-Associated B-Lymphocytes

CD20-positive lymphocytes of both groups were situated in weak focal infiltrates located in stroma in the invasive front of the tumor (Fig. 2c, d). Median of CD20 cells expression in MELF-pattern positive group was 37.2% (35.4%–47.5%), and in the MELF-pattern negative group this was 36.3% (35.1%–46.2%). No significant difference was observed in TAB infiltration in both groups (p = 0.721). ROC-analysis of TAB revealed that the AUC was 0.56 (p = 0.923). The sensitivity, specificity, and threshold value of the index were 24.6%, 94.4 and 38.3%, respectively.

Tumor-Associated NK-Lymphocytes

Presence of NK cells was also investigated in both groups. These cells were observed in the infiltrate in small clusters of 5 to 10 lymphocytes (Fig. 2e, f). Median of NK cells in group of patients with MELF-pattern was 27.7% (27.1%–39.6%) and in group of patients without MELF-pattern median was 29.7% (22.4%–41.5%). No significant difference was observed between the two groups (p = 0.891). The ROC- analysis of CD57 expression showed that the AUC was 0.68, which was not statistically significant (p = 0.061). The sensitivity, specificity, and threshold indicator were 83.3%, 96.7%, and 30.8%, respectively.

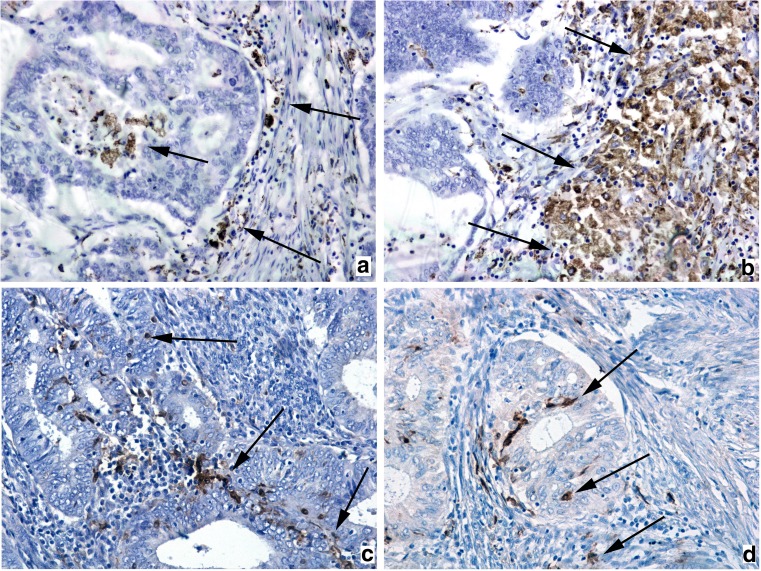

Tumor-Associated Macrophages

In group of patients with MELF-pattern, CD68 macrophages were observed in small infiltrates located near cancer glands (Fig. 3a) (median: 45.5% (38.2%–54.7%)). In cases without MELF-pattern CD68-positive cells were in dense infiltrates, in some cases, in cancer glands (Fig. 3b) (median: 60.3% (44.5%–65.7%)). Mann-Whitney test showed statistically significant difference (p < 0.001) between groups in expression of CD68. On the basis of the ROC-analysis, a total CD68 -positive cells threshold of 37.1% was adopted as the best differentiating value between patients who has MELF-pattern stroma changes and without it, with 75.0% specificity and 74.1% sensitivity (area under the curve was 0.75; p < 0.001).

Fig. 3.

Infiltration of macrophages and dendritic cells in zone of invasion. Immunochistocemistry for CD68: CD68+ tumor-associated macrophages infiltrate lumen of the gland and cancer stroma (arrows) in group with MELF-pattern (a); dense infiltrate by CD68+ tumor-associated macrophages (arrows) of cancer stroma in group without MELF-pattern (b); Immunochistocemistry for S100: infiltration of cancer glands and stroma (arrows) by weak infiltrates presented by few S100+ tumor-associated dendritic cells in both groups (c-d). Magnification: ×200. Counterstain: Hematoxylin

Tumor Associated Dendritic Cells

S100-positive DC of MELF-positive group were situated in weak local infiltrates predominantly in glands (Fig. 3c). DC in MELF-negative group also formed weak infiltrates, however they were located mainly in stroma in surrounding tumor glands (Fig. 3d). Median of S100 cells expression in MELF-pattern positive group was 27.2% (25.5%–41.3%) and in MELF-pattern negative group was 28.1% (25.6%–35.6%). No significant difference was observed in DC infiltration in both groups (p = 0.853). ROC-analysis of S100 revealed that the AUC was 0.53 (p = 0.641). The sensitivity, specificity, and threshold value of the index were 27.2%, 60.3 and 62.9%, respectively.

Correlation Analysis

Our study demonstrated a significant correlation between the presence of MELF-pattern and a decrease of CD3 positive T-lymphocytes (r = 0.691; p < 0.001). Also, an inverse correlation was observed between the presence of MELF-pattern and TAM (r = 0.568; p = 0.001). Correlation analysis described that changes in cancer stroma (MELF-pattern) are associated with a reduction in TAT and TAM in zone of invasion.

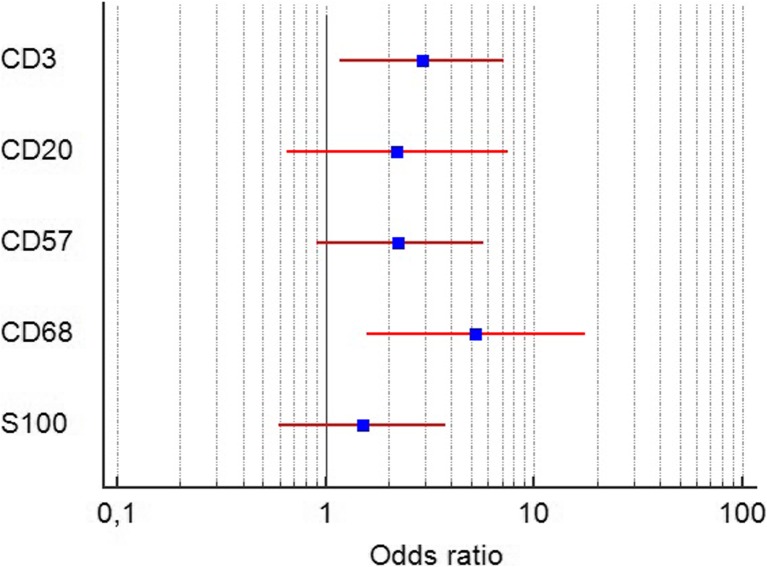

Odds Ratio

A presence of TAT cells in peritumoral infiltrate less than the threshold criteria increased risk of MELF-pattern (OR = 2.9; 95% CI 1.7 to 7.2; p = 0.002). Also, a reduction of TAM in immune cells peritumoral infiltrate was associated with the presence of MELF-pattern (OR = 5.3; 95% CI 1.6 to 17.6; p = 0.007). Other tumor associated immune cells did not change OR of MELF-pattern as shown Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Forest plot represents odds ratio and 95% confidence interval of the association between infiltration by each type of immune cell and MELF-pattern stromal changes. The result of analysis showed statistically significant association between decrease of TAT and TAM and presence of MELF-pattern. Abbreviations: CD3 – tumor-associated CD3+ T-lymphocytes; CD20 – tumor-associated CD20+ B-lymphocytes; CD57 – tumor-associated CD57+ NK-lymphocytes; CD68 – tumor-associated CD68+ macrophages; S100+ − tumor-associated S100+ dendritic cells

Discussion

Cancer cells directly interact with the immune system through paracrine signaling and direct cell-cell contact in order to suppress their anti-cancer function and promote tumor spreading and metastasis [12]. Cancer cells also interact with their stroma, remodeling their extracellular matrix to facilitate their own invasion and metastatic dissemination. The cycle completes through interactions between the tumor stroma and the immune system wherein the stiff, hypoxic and inflamed tumor microenvironment affect immune cell behavior [13]. Our research revealed importance of such specific interactions between immune cells and cancer stroma with MELF-pattern.

T cells are a class of immune cells representing the key actors of the adaptive immune response. Increasing evidence indicates that the high rate of infiltration of T-lymphocytes is an indicator of good prognosis [14]. Cancer cells perform fermentative glycolysis in their hypoxic milieus to generate adequate energy to sustain their growth. In terms of the immune response, this translates to increased concentrations of lactic acid which have been reported to decrease the cytotoxicity of TAT and NK, through a reduction of interferon-α production. In fact, tumor-cell derived lactic acid suppresses cytotoxic T-cell proliferation, impairs T-cell cytokine production, and eventually kills up to 60% of the T-cells after 24 h [15, 16]. According to this data we can expect that a reduction of TAT in MELF-positive cases may be a specific manifestation of MELF-pattern stroma interaction with immune cells by tumor signals and metabolism products.

The role of TAB in the pathogenesis and treatment of cancer has not received as much attention as the role of T cells [17]. TAB can potentially inhibit the development and progression of cancers by making antitumor antibodies or by differentiating into appropriate effector B-cells. Some studies indicate that TABs are crucial for the proper functioning of effector T cells in the tumors and their depletion results in tumor progression [18]. At present, the role of TAB in solid cancers is insufficiently characterized and controversial. We did not observe any differences between EA with and without MELF-pattern in number of this cells. Therefore, we can deduce that this type of cells does not have direct interactions with MELF-pattern stroma.

NK cells are innate lymphoid cells that constitute up to 15% of lymphocytes in peripheral blood. In tumors, NK cells are preferentially localized in stromal compartment [9]. These cells were reported to have scarce contact with tumor cells. NK cells are crucial for tumor immune surveillance and their elevated numbers in tumors are associated with favorable prognosis [19]. Activated NK cells bear high cytolytic potential and induce contact apoptosis in target cells by releasing perforins, granzymes, and through cell death ligands such as CD95L and TRAIL. NK cell– mediated destruction of tumor cells depends on subtle balance between activating and de-activating signals from NK cell receptors [18]. In our research NK cells, no significant difference was observed between the two groups. This may be explained by Levy EM et al., who reported that NK cells are not found in large numbers in advanced human neoplasms, indicating that they do not normally home efficiently to malignant tissues [20]. Thus, we predict that low number of these cells in immune cells infiltrate did not demonstrate any significant difference in cases with and without MELF-pattern.

The TAMs are an important component of the inflammatory cells within the tumor stroma. Evidence suggests that macrophages may account for the major part of the host leukocyte infiltrate in the majority of human malignant tumors [7, 21]. Several investigators had counted the TAM in cancer surgical specimen under microscopy by immunohistochemical staining and reported that the percentage of TAM in human malignancies is between 10 and 65% [22, 23]. Tissues that contain a high proportion (>50%) of immature fibroblasts correlate with decreased TAMs, epithelial–mesenchymal transition, and poor prognosis [24]. A reduction of TAM in peritumoral infiltrate is often associated with poor prognosis, because of reduction of M1 macrophages, with no changes in M2 polarized macrophages, which are recruited by cancer cells and decrease of stroma fibroblasts layer formation and maturation [25]. According to this data, reduced number of TAMs in MELF-pattern positive EA was associated with interactions between cancer-associated fibroblasts of MELF-pattern areas and TAM, suggesting that these cells may play role in maturity of cancer-association fibroblasts in EA with these specific changes.

DCs are the primary cell population responsible for initiating antitumor immunity, and thus it is not surprising that tumors develop mechanisms for inhibiting DC function and longevity [12]. The tumor-mediated interference with DC generation, function, and survival represents one pathway by which tumors escape host immune mechanisms via inhibiting the activity of DC [26, 27]. These cells are found in many types of solid tumors and are crucial for presentation of tumor antigens and activation of antitumor T cells [28]. It was reported that immature DCs in melanoma and colorectal cancer infiltrate both tumor islets and stroma, whereas mature DCs tend to localize in peritumoral stroma in close association with lymphocytes [29]. However, in our study we did not observe any differences between MELF-positive and MELF-negative groups in number of DC. This may suggest that DCs’ role in immune response to tumor may not be dependent on its number but functional activity.

Our data demonstrates a similar pattern observed in cancer immune contextures classification which was proposed by E. Becht et al. [30]. The immune contexture described by authors is the result of interactions between malignant cells and their microenvironments, including not only immune but also inflammatory, angiogenic, and fibroblastic components [31]. Cases without MELF-pattern in our study demonstrate a high level of TAT, TAM and good prognosis of patients’ survival, which suggests that this type of EA is “immunogenic tumor”. Thus, we suppose that the cases of EA with MELF-pattern are “inflammatory tumors”, because they have low levels of TAT, TAM and poor patients survival [32].

Conclusion

H. Jiang et al. [33] described that the cancer stroma fibrosis is one of the main regulators of tumor immune cells infiltration by cascades of signal molecules [33]. Our research revealed that MELF-pattern in specific cancer stroma fibrosis has immune cells infiltration where TAT and TAM cells are found at a reduced number. Previously, we described a correlation between differential MELF-pattern and survival of patients with EA [11]. In the current study, we present that changes in immune cells infiltration in cancerous stroma may also contribute to EA progression and may be a manifestation of aggressive potential of MELF-pattern in cancer development. Also, according to our OR analysis, a low level of TAT and TAM cells indicated an increased risk of MELF-pattern presence. Thus, this study suggests that MELF pattern has specific distribution in antitumor immune response, which may be used as a target for specific therapy or prognosis of EA with these stromal changes. Also, the immune contexture classification give opportunity for new focus to the treatment of EA. However, a large independent cohort of samples should be utilized in the future to validate our findings.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the patients who agreed for participating in this study and reviewers for their constructive comments.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the Committees for Medical and Health Sciences of Research Ethics of Gomel State Medical University and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Dispensation from the requirement of patient consent was granted.

References

- 1.Kojiro-Sanada S, Yasuda K, Nishio S, et al. CXCL14-CXCR4 and CXCL12-CXCR4 axes may play important roles in the unique invasion process of endometrioid carcinoma with MELF-pattern myoinvasion. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2017;36:530–539. doi: 10.1097/pgp.0000000000000362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naki MM, Oran G, Tetikkurt SÜ et al (2017) Microcystic, elongated and fragmented (MELF) pattern of invasion in relation to histopathological and clinical prognostic factors in endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma. Journal of the Turkish-German Gynecological Association. 10.4274/jtgga.2017.0016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Kihara A, Yoshida H, Watanabe R, et al. Clinicopathologic association and prognostic value of microcystic, elongated, and fragmented (MELF) pattern in endometrial endometrioid carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41:896–905. doi: 10.1097/pas.0000000000000856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanci M, Güngördük K, Gülseren V et al (2017) MELF pattern for predicting lymph node involvement and survival in grade I-II endometrioid-type endometrium cancer. Int J Gynecol Pathol:1. 10.1097/pgp.0000000000000370 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Stewart CJR, Little L. Immunophenotypic features of MELF pattern invasion in endometrial adenocarcinoma: evidence for epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Histopathology. 2009;55:91–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2009.03327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stewart CJ, Crook ML. Galectin-3 expression in uterine endometrioid adenocarcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2010;29:555–561. doi: 10.1097/pgp.0b013e3181e4ee4ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petty AJ, Yang Y. Tumor-associated macrophages: implications in cancer immunotherapy. Immunotherapy. 2017;9:289–302. doi: 10.2217/imt-2016-0135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quail DF, Joyce JA. Microenvironmental regulation of tumor progression and metastasis. Nat Med. 2013;19:1423–1437. doi: 10.1038/nm.3394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shurin MR et al. (2016) Tumor Immunoenvironment. Springer, S.l.

- 10.Zinovkin DA, Pranjol MZI, Petrenyov DR, et al. The potential roles of MELF-pattern, microvessel density, and vegf expression in survival of patients with endometrioid endometrial carcinoma: a morphometrical and immunohistochemical analysis of 100 cases. Journal of Pathology and Translational Medicine. 2017;51:456–462. doi: 10.4132/jptm.2017.07.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zinovkin D, Pranjol MZI. Tumor-infiltrated lymphocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells in endometrioid adenocarcinoma of corpus uteri as potential prognostic factors. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2016;26:1207–1212. doi: 10.1097/igc.0000000000000758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dunn GP, Bruce AT, Ikeda H, et al. Cancer immunoediting: from immunosurveillance to tumor escape. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:991–998. doi: 10.1038/ni1102-991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seager RJ, Hajal C, Spill F, et al. Dynamic interplay between tumour, stroma and immune system can drive or prevent tumour progression. Convergent Science Physical Oncology. 2017;3:034002. doi: 10.1088/2057-1739/aa7e86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maluf PJ, Michelin MA, Etchebehere RM, et al. T lymphocytes (CD3) may participate in the recurrence of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade III. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008;278:525–530. doi: 10.1007/s00404-008-0621-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brand A, Singer K, Koehl GE, et al. LDHA-associated lactic acid production blunts tumor immunosurveillance by t and nk cells. Cell Metab. 2016;24:657–671. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dietl K, Renner K, Dettmer K, et al. Lactic acid and acidification inhibit tnf secretion and glycolysis of human monocytes. J Immunol. 2009;184:1200–1209. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spaner D, Bahlo A. B lymphocytes in cancer immunology. In: Medin J, Fowler D, editors. Experimental and applied immunotherapy. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stakheeva M, Riabov V, Mitrofanova I, et al. Role of the immune component of tumor microenvironment in the efficiency of cancer treatment: perspectives for the personalized therapy. Curr Pharm Des. 2017;23:1–20. doi: 10.2174/1381612823666170714161703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pegram HJ, Haynes NM, Smyth MJ, et al. Characterizing the anti-tumor function of adoptively transferred NK cells in vivo. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2010;59:1235–1246. doi: 10.1007/s00262-010-0848-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levy E, Bianchini M, Euw EV et al (2008) Human leukocyte antigen-E protein is overexpressed in primary human colorectal cancer. Int J Oncol. 10.3892/ijo.32.3.633 [PubMed]

- 21.Yuan Ang, Chen Jeremy J.‐W., Yang Pan‐Chyr. Advances in Clinical Chemistry. 2008. Pathophysiology of Tumor‐Associated Macrophages; pp. 199–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Biswas SK, Sica A, Lewis CE. Plasticity of macrophage function during tumor progression: regulation by distinct molecular mechanisms. J Immunol. 2008;180:2011–2017. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Slayton WB, Hu Z. Tumor microenvironment. 2010. Bone marrow stroma and the leukemic microenvironment; pp. 99–133. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ha SY, Yeo S-Y, Xuan Y-H, Kim S-H. The prognostic significance of cancer-associated fibroblasts in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS One. 2014;9:e99955. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng X, Turkowski K, Mora J, et al. Redirecting tumor-associated macrophages to become tumoricidal effectors as a novel strategy for cancer therapy. Oncotarget. 2017;8:48436–48452. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shurin MR, Salter RD. Dendritic cells in cancer. New York, NY: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tashireva L. A., Perelmuter V. M., Manskikh V. N., Denisov E. V., Savelieva O. E., Kaygorodova E. V., Zavyalova M. V. Types of immune-inflammatory responses as a reflection of cell–cell interactions under conditions of tissue regeneration and tumor growth. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2017;82(5):542–555. doi: 10.1134/S0006297917050029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pasqual G, Chudnovskiy A, Tas JMJ, et al. Monitoring T cell–dendritic cell interactions in vivo by intercellular enzymatic labelling. Nature. 2018;553:496–500. doi: 10.1038/nature25442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Janco JMT, Lamichhane P, Karyampudi L, Knutson KL. Tumor-infiltrating dendritic cells in cancer pathogenesis. J Immunol. 2015;194:2985–2991. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1403134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Becht Etienne, Giraldo Nicolas A., Germain Claire, de Reyniès Aurélien, Laurent-Puig Pierre, Zucman-Rossi Jessica, Dieu-Nosjean Marie-Caroline, Sautès-Fridman Catherine, Fridman Wolf H. Advances in Immunology. 2016. Immune Contexture, Immunoscore, and Malignant Cell Molecular Subgroups for Prognostic and Theranostic Classifications of Cancers; pp. 95–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fridman WH, Pagès F, Sautès-Fridman C, Galon J. The immune contexture in human tumours: impact on clinical outcome. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:298–306. doi: 10.1038/nrc3245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Becht E, Giraldo NA, Dieu-Nosjean M-C, et al. Cancer immune contexture and immunotherapy. Curr Opin Immunol. 2016;39:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2015.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang H, Hegde S, Denardo DG. Tumor-associated fibrosis as a regulator of tumor immunity and response to immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2017;66:1037–1048. doi: 10.1007/s00262-017-2003-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]