Abstract

Ovarian cancer (OC) ascites is an inflammatory and immunosuppressive tumor environment characterized by the presence of various cytokines, chemokines and growth factors. The presence of high concentrations of these cytokines/chemokines in ascites is associated with a more aggressive tumor phenotype. IL-10 is an immunosuppressive cytokine for which high expression has been associated with poor prognosis in some cancers. However, its role on OC tumor cells has not been explored. Therefore, the aim of the current study was to elucidate the role of ascites IL-10 on the proliferation, migration and survival of OC cell lines. Here, we show that IL-10 levels are markedly increased in patients with advanced serous OC ascites relative to serous stage I/II ascites and peritoneal effusions from women with benign conditions. Ascites and IL-10 dose-dependently enhanced the proliferation and migration of OC cell lines CaOV3 and OVCAR3 but had no effect on cell survival. IL-10 levels in ascites positively correlated with the ability of ascites to promote cell migration but not proliferation. Depletion of IL-10 from ascites markedly inhibited ascites-induced OC cell migration but was not crucial for ascites-mediated cell proliferation. Taken together, our findings establish an important role for IL-10, as a component of ascites, in the migration of tumor cells.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12307-018-0215-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Ovarian carcinoma, Ascites, IL-10, Cell migration, Cell proliferation

Introduction

Ovarian cancer (OC) is the second most frequent gynecological cancer and has a poor prognosis because progression is often asymptomatic. Consequently, OC is often detected at advanced stages (III/IV) with widespread intraperitoneal metastasis and large amount of ascites [1, 2]. OC dissemination results from a sequential process in which tumor cells shed from the primary tumor into ascites throughout the peritoneal cavity [1, 2]. Malignant ascites greatly facilitates this process and its presence at diagnostic correlates with peritoneal spread of the tumor and with a decreased 5-year survival rate [3–5]. A variety of cytokines, chemokines and growth factors are present in OC ascites [6–8]. There is growing evidence that cytokines/chemokines within ascites contributes to tumor progression by creating a proliferative, migrating and prosurvival environment [9–12]. Indeed, OC ascites have been shown to enhance OC tumor cell proliferation, migration and survival [13–17].

Cytokines and chemokines, as part of the tumor environment, are important components of cancer-related inflammation and immunity, which may play a pivotal role in tumor progression and metastasis. IL-10, a potent immunosuppressive cytokine which is frequently overexpressed in tumors, plays an important role in protecting cancer cells from immune-mediated destruction [18]. IL-10 is secreted by a wide variety of cell types including macrophages, T cell subsets and cancer cells [19–26]. Multiple studies have found a positive correlation between IL-10 levels (both in serum and within the tumor) and poor prognosis for the patient in different cancers, including melanoma [27–30], lung cancer [24] and T/NK-cell lymphomas [31]. IL-10 has pleiotropic effects which vary greatly depending on both the experimental context and the cell types under investigation.

High levels of IL-10 are found in the serum and ascites of OC patients [6, 8, 32–34]. Furthermore, IL-10 consistently correlate with advanced disease and poor patient prognosis in OC [32, 34–36]. Ascites-associated IL-10 contribute to decrease dendritic cell activation and reduced T-cell stimulatory activity [37]. IL-10 was recently shown to increase programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) surface expression on dendritic cells creating an immune escape loop [38]. Furthermore, a combination of PD-1 blockade and disruption of IL-10/IL-10R signaling enhanced endogenous anti-tumor immunity, resulting in improved survival and reduced tumor burden in a mouse model [38]. However, the exact roles IL-10 plays in ascites and whether it contribute to tumorigenesis by directly affecting tumor cells is unclear.

In this study, we aim to investigate the contribution of the tumor environment to the proliferation, migration and survival of OC cells. We demonstrate that high levels of IL-10 are present in stage III/IV serous OC ascites and that IL-10 is an important component of ascites for the ascites-mediated migration of OC cells.

Material and Methods

Patients

Ascites is routinely obtained at the time of the debulking surgery of ovarian cancer patients treated at the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Sherbrooke. After collection, cell-free ascites are stored at −80 °C in our tumor bank until use. The study population consisted of 57 women with newly diagnosed epithelial serous ovarian cancer admitted at the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Sherbrooke (CHUS). Ten cases with benign conditions, namely histologically benign gynecological conditions including fibromas, endometriosis, mucinous and serous cystadenomas constituted the control group. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Centre de Recherche of CHUS. Informed consent was obtained from women that underwent surgery by the gynecologic oncology service between 2000 and 2017. All samples were reviewed by an experienced pathologist. Baseline characteristics and serum CA125 levels were collected for all patients. All patients had follow up ≥12 months. FIGO staging criteria defines stage I/II OC has a disease limited to ovaries or fallopian tubes with or without extension to the pelvic cavity. Stage III/IV disease involves spreading outside the pelvic cavity into the peritoneal cavity or at distant sites outside the peritoneal cavity. Disease progression was defined by either serum CA125 ≥ 2 X nadir value on two occasions, documentation of lesion progression or appearance of new lesions on CT-scan or death. Patient’s conditions were staged according to the criteria of the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO). PFS was defined by the time from the initial surgery to evidence of disease progression. Overall survival was defined by the time from the initial surgery to death (any cause).

Cell Culture and Reagents

The human OC cell lines CaOV3 and OVCAR3 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and maintained in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C. Cells were passaged twice weekly. OVCAR3 cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 (Wisent, St-Bruno, QC, Canada) supplemented with 20% FBS, insulin (10 mg/L), glutamine (2 mM) and antibiotics. CaOV3 cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 (Wisent) supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM glutamine and antibiotics. Human recombinant TRAIL was purchased from PeproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ). Human recombinant IL-10 was from RnD Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Neutralizing anti-IL-10 antibody (clone JES3-19F1) was from Biolegend (Cedarlane, Burlington, ON). The JES3-19F1 antibody can neutralize the bioactivity of natural or recombinant IL-10. Acellular ascites fractions were obtained at the time of initial cytoreductive surgery from women with advanced serous ovarian carcinomas. Ascites samples were supplied by the Banque de tissus et de données cliniques et biologiques sur les cancers gynécologiques et du sein de Sherbrooke as part of the Banque de tissus et de données du Réseau de Recherche en Cancer des Fonds de Recherche du Québec en Santé (FRQS) affiliated to the Canadian Tumor Repository Network (CTRNet).

Migration Assay

Cells (5 × 103) were suspended in 500 μl FBS and hormone-free DMEM/F12 and were seeded in the top chamber of monolayer-coated polyethylene terephthalate membranes cell culture inserts (24-wells insert, 8 μm pore size). The bottom chamber contained 0.75 ml DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum, 10% ascites, or IL-10 at concentrations ranging from 0 to 25 ng/ml depending on the experiments. The cells were incubated for 16–20 h, and cells that remained in the upper chamber were removed by scraping with a cotton swab. Cells that migrated through the membrane were fixed with ice cold methanol for 10 min and stained with a 0.5% crystal violet, 20% (v/v) hematoxylin solution in ethanol for 15 min. After several washes in PBS, membranes were allowed to dry before being mounted on a glass slide. Ten random fields were counted at × 100 magnification.

Cytoxicity Assays

Cell viability was determined by the XTT assay. Briefly, cells were plated at 20,000 cells/well in 96-well plates. The next day, cells (confluence 60–70%) were treated with increasing of cisplatin and a fixed concentration of IL-10, as indicated, and cells incubated for 48 h. At the termination of the experiment, the culture media was removed and a mixture of PBS and fresh media (without phenol red) containing phenazine methosulfate and XTT (Sigma) was added for 30 min. The absorbance of each well was determined using a microplate reader at 450 nm (TecanSunrise, Research Triangle Pack, NC). The percentage of cell survival was defined as the relative absorbance of treated versus untreated cells. All assays were performed in triplicate and repeated three times. Similar experiments were performed with increasing concentrations of human recombinant TRAIL, instead of cisplatin.

Cell Proliferation Assays

The effect of IL-10 on cell growth was determined by XTT assay. Cells were suspended in complete medium and plated into 96-well plates at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well. Cells were cultured for various times in complete medium before adding XTT reagents. After incubation for 1 h at room temperature, the absorbance of each well was determined using a microplate reader at 450 nm. All assays were performed in triplicate and repeated three times. The effect of ascites on cell proliferation was determined by trypan blue exclusion. Cells were suspended in complete medium containing 10% v/v ascites and plated into 96-well plates at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well. Forty eight hours later, cells were suspended and suspensions were counted in a hemacytometer to determine the total number of cells. The number of viable cells in suspensions was determined by counting all dye-excluding cells in a hemacytometer. Assays were performed in triplicate and two hemacytometer counts were performed per replicate.

ELISA Measurements

IL-10 levels in peritoneal fluid samples were determined by ELISA using the commercially available human Quantikine kits from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). The assays were performed in duplicate according to the manufacturer’s protocols. For IL-10, the detection threshold was 1.1 pg/ml, the intra-assay variability was 3.2–3.7% and the inter-assay variability was 3.5%. All samples were analyzed in triplicates and the median values were used for statistical analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical comparisons between two groups were performed using the Mann-Whitney or Student’s t-test. The correlation between IL-10 and ascites-mediated proliferation and migration was determined by the Pearson’s correlation test. Statistical differences in PFS or overall survival were determined by the log-rank test, and Kaplan-Meier survival curves were made. Statistical significance was indicated by P < 0.05.

Results

IL-10 Levels Are Higher in Ascites from Patients with Advanced Serous OC

We initially evaluated IL-10 levels in serous stage I/II and III/IV OC ascites and in peritoneal fluids from patients with benign diseases (mostly fibroma). IL-10 levels did not significantly differ among benign peritoneal fluids and stage I/II serous OC ascites (median 10 pg/ml vs 0.14 pg/ml; P = 0.924; Fig. 1a). However, IL-10 levels were significantly higher in stage III/IV serous OC ascites (median 46.6 pg/ml) compared to benign fluids and stage I/II serous ascites (P = 0.0002). Although there was a trend toward shorter progression-free survival and overall survival, high IL-10 levels in serous OC ascites were not significantly associated with shorter progression-free survival (median 12 months vs 17 months for low IL-10 levels; P = 0.120 by log rank test; Fig. 1b) or decreased overall survival (median 32 months vs 42 months for low IL-10 levels; P = 0.177 by log rank test; Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1.

IL-10 levels in ovarian cancer ascites. a The concentration of IL-10 in benign fluids (n = 10), stage I/II serous ovarian cancer ascites (n = 7) and stage III/IV ascites (n = 50) was determined by ELISA. Box plot representing levels of IL-10. b Kaplan-Meier curve of ascites IL-10 levels. The median IL-10 level (46.6 pg/ml) was taken as the cutoff point

IL-10 Promotes OC Cell Proliferation and Migration but Not Drug Resistance

We first examined the effects of IL-10 on the OC cells migration using CaOV3 and OVCAR3 cell lines, two commonly used OC cell line models. Cells were exposed to increasing concentrations (0 to 25 ng/ml) of IL-10 and migration was determined using Transwell Boyden chambers. The range of IL-10 concentrations selected were within the range of those found in stage III/IV serous OC ascites (Fig. 1a). IL-10 significantly stimulated the migration of CaOV3 and OVCAR3 cell lines in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2a). Unlike CaOV3 cells, OVCAR3 cells are non-invasive in Boyden chambers and non-motile on plastic [39]. In line with the low motility potential of OVCAR3 cells, the magnitude of ascites-mediated migration was lower in these cells relative to CaOV3. Nonetheless, we observed a dose-dependent effect of IL-10 on OVCAR3 cell migration (Fig. 2a). To determine whether IL-10 promotes OC cell growth, we evaluated the effect of increasing concentrations of IL-10 on CaOV3 and OVCAR3 cell proliferation. At lower IL-10 concentrations (10 to 100 pg/ml), we observed a significant increased cell proliferation in OC cell lines (Fig. 2b). However, this effect was lost with higher IL-10 concentration. Because ascites has been shown to inhibit drug and death-receptor ligand-induced apoptosis in OC cells [13–15], we determined whether IL-10 could inhibit cisplatin-induced cell death. Cisplatin or its derivatives are commonly used for first-line treatment of OC. As shown in Fig. 2c, IL-10 (10 ng/ml) did not significantly protect against cisplatin-induced cell death. This was consistent for both CaOV3 and OVCAR3 cell lines. Concentrations of IL-10 up to 3000 pg/ml (range 10 to 3000 pg/ml) led to similar results (Supplementary data, Figure 1). Furthermore, IL-10 (50 to 3000 pg/ml) failed to inhibit death receptor ligand TRAIL-induced cell death (Supplementary data, Figure 2).

Fig. 2.

IL-10 enhance the migration of tumor cells. a The migration of ovarian cancer CaOV3 cells (left panel) and OVCAR3 cells (right panel) was evaluated at 24 h using Boyden chambers with either serum-free medium (control) or different concentrations (0–25 ng/ml) of IL-10 as chemoattractants. b On day 0, 5000 cells were incubated in media supplemented with no serum or 0–1000 pg/ml of IL-10 for 48 h. Cell growth was determined by XTT assay. CaOV3 cells (left panel) and OVCAR3 cells (right panel). * indicates P < 0.05. Values are presented as mean ± SEM and represent three independent experiments (c) CaOV3 cells (left panel and OVCAR3 cells (right panel) were incubated in media with no serum containing IL-10 (10 ng/ml) for 24 h. Cells were then challenged with increasing concentration of cisplatin (0 to 50,000 ng/ml). Cell viability was determined by XTT assay after 48 h. Values are presented as mean ± SEM and represent three independent experiments

Ascites Promote OC Cell Proliferation and Migration

We examined the effect of serous OC ascites on the migration of CaOV3 and OVCAR3 cell lines. CaOV3 cells were exposed to different ascites (10% v/v) obtained from patients with advanced serous OC and migration was determined using Boyden Transwell chambers. The concentration of ascites used in this study was based on previous studies demonstrating a biological effect of ascites on OC cells at this concentration [17, 40]. Although the magnitude of the effect on cell migration was variable, 5 out of 6 OC ascites samples significantly enhanced migration of CaOV3 cells (Fig. 3a). Migration was also enhanced by serous OC ascites when tested with OVCAR3 cells (Fig. 3a). To determine the effect of serous ascites on proliferation rates, we tested their ability to alter the growth potential of CaOV3 and OVCAR3 cells. Cells were incubated for 48 h in serum-free media (control) or supplemented with 10% of the indicated ascites and cell growth was quantified by Trypan Blue exclusion assay. The highest growth rates were observed with OVC405 ascites, whereas the remaining ascites conferred significant, but variable growth rates (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

Ovarian cancer ascites promotes cell migration. a The migration of ovarian cancer CaOV3 cells was evaluated at 24 h using Boyden chambers with either serum-free medium (control) or different serous OC ascites as chemoattractants (concentration 10% v/v). b Migration of CaOV3 cells with increasing concentration of OVC439 ascites evaluated at 24 h. c Migration of ovarian cancer OVCAR3 cells in the presence of either OVC439 or OVC469 (10% v/v). d On day 0, 5000 cells were incubated in media supplemented with no serum or 10% v/v serous OC ascites for 48 h. Cell growth was determined by Trypan Blue exclusion assay. CaOV3 cells (left panel) and OVCAR3 cells (right panel). e Proliferation of CaOV3 cells in the presence of increasing concentrations of OVC439 (0 to 25% v/v). * indicates P < 0.05. Values are presented as mean ± SEM and represent three independent experiments

Ascites-Induced Cell Migration Positively Correlates with the IL-10 Levels of OC-Associated Ascites

We assessed whether ascites IL-10 levels correlated with the observed migrating effect of ascites (Table 1). We found a positive correlation between the levels of IL-10 and the migrating effect of serous ascites (Fig. 4a). In contrast, levels of IL-10 in ascites did not significantly correlated with the proliferative effect of ascites (Fig. 4b).

Table 1.

IL-10 ascites levels in relation to CaOV3 cell migration

| Sample number | Sub-type | Stage | Mean number of cells/field | Ascites IL-10 levels (pg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OVC454 | Serous | IIIA | 11 | 4.2 |

| OVC451 | Serous | IB | 19 | 17.7 |

| OVC405 | Serous | IV | 87 | 28.5 |

| OVC469 | Serous | IIIC | 87 | 401.6 |

| OVC427 | Serous | IIIC | 107 | 263.5 |

| OVC439 | Serous | IIIC | 109 | 47.6 |

| OVC346 | Serous | IIIC | 351 | 153.7 |

Fig. 4.

IL-10 levels in ascites correlates with ability of ascites to stimulate CaOV3 cell migration. The correlation coefficient (r) was determined by Pearson’s correlation coefficient test. a Correlation between ascites-induced CaOV3 cell migration and ascites IL-10 concentration. b Correlation between ascites-induced CaOV3 cell proliferation and ascites IL-10 concentration

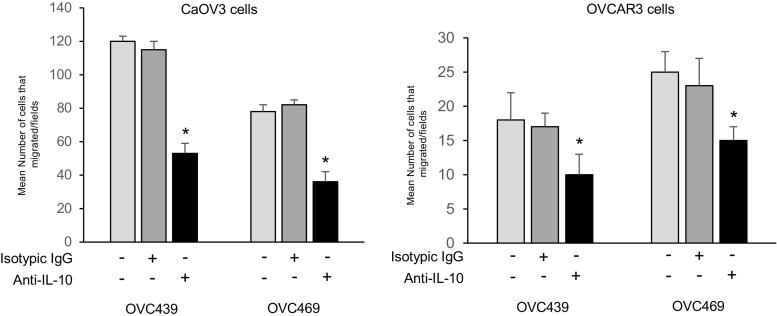

IL-10 Is a Component of Ascites Responsible for the Stimulation of Cell Migration

Given the data above showing the presence of high IL-10 levels in stage III/IV serous ascites and levels positively correlating with ascites-induced migration, we assess the role of ascites IL-10 in cell migration activity. To this end, OVC439 and OVC469 ascites were incubated with a neutralizing antibody against IL-10 for 24 h and then we determined their abilities to stimulate the migration of CaOV3 and OVCAR3 cells. As shown in Fig. 5a, the ascites-induced migration of OC cells was significantly inhibited by the pre-incubation of ascites with the IL-10-blocking antibody. Although significant (P < 0.001), the IL-10-blocking antibody only achieved a partial (40 to 57%) inhibition of ascites-induced migration suggesting the possible contribution of other factors in this process. Nonetheless, our data suggest that IL-10 is an important factor in ascites that promotes the migration of OC cells. In contrast to these results, IL-10 neutralizing antibody had no effect on ascites-induced cell proliferation on CaOV3 and OVCAR3 cells (Supplementary data, Figure 3).

Fig. 5.

Ascites IL-10 contributes to ascites-induced cell migration. CaOV3 (left panel) and OVCAR3 cells (right panel) were incubated in serum-free media containing ascites (OVC439 and OVC469 with IL-10 blocking antibody (20 μg/ml). Cell migration was determined 24 h later. Values are presented as mean ± SEM and represent three independent experiments. * indicates P < 0.05

Discussion

Ovarian cancer is a highly metastatic disease characterized by widespread intraperitoneal dissemination and ascites formation. Reciprocal interactions between the ascites and tumor cells likely play an important role in OC progression. Cytokine production is associated with immunosuppression and high levels are found in ascites from advanced OC [6, 8, 32–34, 41]. In the present study, we show that IL-10 is present at significantly higher levels in ascites obtained from women with advanced serous OC compared to women with stage I/II serous OC or benign gynecological conditions. This is consistent with previous data showing high levels of IL-10 in ovarian cancer patients [6, 8, 32–34]. Although, in our study, women with high ascites levels of IL-10 generally had a worse outcome compared to women with low IL-10, the difference did not reach statistical significance. This contrast with previous reports showing an association between IL-10 levels and a worse outcome [35, 36]. The main difference between our study and previous studies is that we included only patients with serous OC. The inclusion of other sub-types such as mucinous OC could have yield to different results as ascites from patients with mucinous sub-type OC have about 2-fold higher ascites IL-10 levels relative to serous OC (Matte, unpublished data). Furthermore, the lack of significant association between ascites IL-10 levels and poor survival is perhaps not surprising given the complex nature of OC ascites. The overall outcome is most likely the results of the combined effect of each individual factor affecting tumor cell behavior.

Although the effects of OC ascites on tumor cells growth rates, migration and survival result from the combined effect of different factors, it is important to understand how each component of ascites may affect the biological characteristics of OC cells. OC ascites have been previously shown to stimulate cell growth, to enhance cell migration and to decrease drug-induced apoptosis [13–17]. Consistent with these data, we observed that serous OC ascites stimulated tumor cell proliferation and migration. These ascites-mediated effects were lost when samples were heated (data not shown) suggesting that the effects are due to protein rather than other types of soluble factors. We observed that addition of recombinant IL-10 had, at best, a modest stimulatory effect on cell growth rates of OC cell lines. Recombinant IL-10 stimulating effect on cell growth was completely abrogated by the addition of anti-IL-10 blocking antibody (data not shown). The limited effect of recombinant IL-10 on OC cell proliferation is in line with previous data showing little or no effect of secreted IL-10 on OC cell line growth kinetics [42]. Depletion of ascites IL-10 using a neutralizing anti-IL-10 antibody had no effect on ascites-mediated tumor cell proliferation suggesting that IL-10 is not one of the soluble factor in ascites responsible for the stimulated cell growth. This is perhaps not surprising given the modest effect of recombinant IL-10 on OC cell proliferation and the fact that other ascites factors such as Hepatocyte Growth Factor (HGF), IL-6 and lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) have been shown to stimulate OC cell proliferation [43–45]. Therefore, the blockade of ascites IL-10 is likely overcomed by the presence of other growth-enhancing factors in ascites. In addition, as both IL-6 and IL-10 activate STAT3 signaling, which is involved in cell proliferation, the blockade of IL-10 signaling in the presence of IL-6 will still lead to STAT3 activation and cell proliferation.

The present study suggests the importance of IL-10 in ascites-mediated cell migration. Firstly, we showed that recombinant IL-10 significantly enhanced OC cell migration. Secondly, we found a positive correlation between the levels of IL-10 in ascites and their ability to enhance cell migration. Thirdly, we showed that a IL-10 blocking antibody significantly inhibited ascites-induced cell migration. These finding however do not rule out the possible involvement of other factors from ascites in tumor cell migration. For example, fibronectin, lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), IL-6 and CCL2 have all been shown to enhance OC migration and these factors may be present at high level in ascites [46–49]. Indeed, the fact that IL-10 blockade only partially abrogate ascites-mediated cell migration is in line with this possibiliy and raises the possibility that other factors in ascites can act through other signaling pathways to stimulate cell migration. Interestingly, IL-10 has been shown to activate CIP2A transcription in lung tumor cells [50]. CIP2A has been shown to have an oncogenic role in human malignancies, operating via inactivation of PP2A and stabilization of c-Myc protein. CIP2A is involved in the regulation of laryngeal carcinoma cell migration [51]. Therefore, it is conceivable that IL-10 signal, at least partly, through the CIP2A pathway to stimulate cell migration.

Although serous OC ascites contain relatively high levels of IL-10 with a median of 46.6 pg/ml, the source of IL-10 found in ascites has not been precisely determined. Well-established sources of IL-10 included monocytes, macrophages and T cells. When activated, these cells secrete IL-10 [52]. These cells may be present in OC ascites [53] and therefore contribute to ascites IL-10. Ovarian carcinoma tissues produce and secrete IL-10, which most likely occurs through an autocrine loop [36, 50, 54]. OC cell lines, including CaOV3, can also secrete IL-10 [36]. The activation of peritoneal mesothelial cells with LPS or TNFα stimulate the expression and secretion of IL-10 [55]. Secretion of IL-10 in OC ascites may therefore originate from various cellular sources.

In summary, our data suggest that the kinetics and dynamics of cytokine response might be an important factor for tumor development. The presence of cytokines, such as IL-10, in the peritoneal cavity of OC patients could be important for the growth and development of cancer. IL-10 may have pleiotropic effects in the context of OC. For example, impaired IL-10 signaling limits the establishment of IP ovarian cancer implants in a mouse model, which is associated with increased activation of IP T cell populations and a greater proportion of effector memory cells in the peritoneal cavity, suggesting a role for IL-10 in tumor immune escape [56]. On the other hand, IL-10 directly acts on tumor cells to promote cell migration. Thus, IL-10 exerts both anti-tumor and pro-tumor function in the OC tumor environment.

Electronic supplementary material

(PPT 265 kb)

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funds from the Canadian Institute for Health Research (MOP-244194-CPT-CFDA-48852), the Centre de Recherche Clinique Étienne-Lebel du Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Sherbrooke and the Université de Sherbrooke. Tumor banking were supported by the Banque de tissus et données of the Réseau de recherche sur le cancer of the Fond de recherche du Québec en Santé (FRQS) and Cancer de l’Ovaire Canada, associated with the Canadian Tumor Repository Network (CTRNet). The tissue bank provided malignant ascites and peritoneal fluids.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Bast RC, Hennessy B, Mills GB. The biology of ovarian cancer: new opportunities for translation. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:415–428. doi: 10.1038/nrc2644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ozols RF, Bookman MA, Connolly DC, Daly MB, Godwin AK, Schilder RJ, Xu X, Hamilton TC. Focus on epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:19–24. doi: 10.1016/S1535-6108(04)00002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shen-Gunther J, Mannel RS. Ascites as a predictor of ovarian malignancy. Gynecol Oncol. 2002;87:77–83. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2002.6800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ayhan A, Gultekin M, Taskiran C, Dursun P, Firat P, Bozdag G, Celik NY, Yuce K. Ascites and epithelial ovarian cancers: a reappraisal with respect to different aspects. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2007;17:68–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ayantunde AA, Parsons SL. Pattern and prognostic factors in patients with malignant ascites: a retrospective study. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:945–949. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matte I, Lane D, Laplante C, Rancourt C, Piché A. Profiling of cytokines in human epithelial ovarian cancer ascites. Am J Cancer Res. 2012;2:566–580. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lane D, Matte I, Rancourt C, Piché A. Prognostic significance of IL-6 and IL-8 ascites levels in ovarian cancer patients. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:210. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giuntoli RL, Webb TJ, Zoso A, Rogers O, Diaz-Montes TP, Bristow RE, Oelke M. Ovarian cancer-associated ascites demonstrates altered immune environment: implications for antitumor immunity. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:2875–2884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maccio A, Madeddu C. Inflammation and ovarian cancer. Cytokine. 2012;58:133–147. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2012.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Germano G, Allavena P, Mantovani A. Cytokines as a key component of cancer-related inflammation. Cytokine. 2008;43:374–379. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature01322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:436–444. doi: 10.1038/nature07205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lane D, Robert V, Grondin R, Rancourt C, Piché A. Malignant ascites protect against TRAIL-induced apoptosis by activating the PI3K/Akt in human ovarian carcinoma cells. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:1227–1237. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lane D, Goncharenko-Khaider N, Rancourt C, Piché A. Ovarian cancer ascites protects from TRAIL-induced cell death through αvβ5 integrin-mediated focal adhesion kinase and Akt activation. Oncogene. 2010;29:3519–3531. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goncharenko-Khaider N, Matte I, Lane D, Rancourt C, Piché A. Ovarian cancer ascites increase Mcl-1 expression in tumor cells through ERK1/2-Elk-1 signaling to attenuate TRAIL-induced apoptosis. Mol Cancer. 2012;11:84. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-11-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Puiffe ML, Le Page C, Filali-Mouhim A, Zietarska M, Ouellet V, Tonin PN, Chevrette M, Provencher DM, Mes-Masson AM. Characterization of ovarian cancer ascites on cell invasion, proliferation, spheroid formation, and gene expression in an in vitro model of epithelial ovarian cancer. Neoplasia. 2007;9:820–829. doi: 10.1593/neo.07472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matte I, Lane D, Laplante C, Garde-Granger P, Rancourt C, Piché A. Ovarian cancer ascites enhance the migration of patient-derived peritoneal mesothelial cells via cMet pathway through HGF-dependent and –independent mechanisms. Int J Cancer. 2015;137:289–298. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mannino MH, Zhu Z, Xiao H, Bai Q, Wakefield MR, Fang Y. The paradoxical role of IL-10 in immunity and cancer. Cancer Lett. 2015;367:103–107. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jankovic D, Kugler DG, Sher A. IL-10 production by CD4+ effector T cells: a mechanism for self-regulation. Mucosal Immunol. 2010;3:239–246. doi: 10.1038/mi.2010.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jankovic D, Kullberg MC, Feng CG, Goldszmid RS, Collazo CM, Wilson M, Wynn TA, Kamanaka M, Flavell RA, Sher A. Conventional T-bet(+) Foxp3(−) Th1 cells are the major source of host protective regulatory IL-10 during intracellular protozoan infection. J Exp Med. 2007;204:273–283. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maynard CL, Weaver CT. Diversity in the contribution of interleukin-10 to T-cell-mediated immune regulation. Immunol Rev. 2008;226:219–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00711.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mocellin S, Marincola F, Rossi CR, Nitti D, Lise M. The multifaceted relationship between IL-10 and adaptive immunity: putting together the pieces of a puzzle. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2004;15:61–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Umetsu SE, Winandy S. Ikaros is a regulator of Il10 expression in CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2009;183:5518–5525. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li C, Li H, Jiang K, Li J, Gai X. TLR4 signaling pathway in mouse Lewis lung cancer cells promotes the expression of TGF-β1 and IL-10 and tumor cells migration. Biomed Mater Eng. 2014;24:869–875. doi: 10.3233/BME-130879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gastl GA, Abrams JS, Nanus DM, Oosterkamp R, Silver J, Liu F, Chen M, Albino AP, Bander NH. Interleukin-10 production by human carcinoma cell lines and its relationship to interleukin-6 expression. Int J Cancer. 1993;55:96–101. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910550118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krüger-Krasagakes S, Krasagakis K, Garbe C, Schmitt E, Hüls C, Blankenstein T, Diamantstein T. Expression of interleukin 10 in human melanoma. Br J Cancer. 1994;70:1182–1185. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1994.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boyano MD, Garcia-Vazquez MD, Lopez-Michelena T, Gardeazabal J, Bilbao J, Canavate M, Galdeano AG, Izu R, Diaz-Ramon L, Raton JA, Diaz-Perez JL. Soluble interleukin-2 receptor, intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and interleukin-10 serum levels in patients with melanoma. Br J Cancer. 2000;83:847–852. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen Q, Daniel V, Maher DW, Hersey P. Production of IL-10 by melanoma cells: examination of its role in immunosuppression mediated by melanoma. Int J Cancer. 1994;56:755–760. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910560524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nemunaitis J, Fong T, Shabe P, Martineau D, Ando D. Comparison of serum interleukin-10 (IL-10) levels between normal volunteers and patients with advanced melanoma. Cancer Investig. 2001;19:239–247. doi: 10.1081/CNV-100102550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sato T, McCue P, Masuoka K, Salwen S, Lattime EC, Mastrangelo MJ, Berd D. Interleukin 10 production by human melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 1996;2:1383–1390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boulland ML, Meignin V, Leroy-Viard K, Copie-Bergman C, Brière J, Touitou R, Kanavaros P, Gaulard P. Human interleukin-10 expression in T/natural killer-cell lymphomas: association with anaplastic large cell lymphomas and nasal natural killer-cell lymphomas. Am J Pathol. 1998;153:1229–1237. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65667-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nowark M, Glowacka E, Szpakowski M, Szyllo K, Malinowski A, Kulig A, Tchorzewski H, Wilczynski J. Proinflammatory and immunosuppressive serum, ascites and cyst fluid cytokines in patients with early and advanced ovarian cancer and benign ovarian tumors. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2010;31:375–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gotlieb WH, Abrams JS, Watson JM, Velu TJ, Berek JS, Martinez-Maza O. Presence of interleukin 10 (IL-10) in the ascites of patients with ovarian and other intra-abdominal cancers. Cytokine. 1992;4:385–390. doi: 10.1016/1043-4666(92)90082-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mustea A, Konsgen D, Braicu EI, Pirvulescu C, Sun P, Sofroni D, Lichtenegger W, Sehouli J. Expression of IL-10 in patients with ovarian carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2006;26:1715–1718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berger S, Siegert A, Denkert C, Kobel M, Hauptmann S. Interleukin-10 in serous ovarian carcinoma cell lines. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2001;50:328–333. doi: 10.1007/s002620100196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou J, Ye F, Chen H, Lv W, Gan N. The expression of interleukin-10 in patients with primary ovarian epithelial carcinoma and in ovarian carcinoma cell lines. J Int Med Res. 2007;35:290–300. doi: 10.1177/147323000703500302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brencicova E, Jagger AL, Evans HG, Georgouli M, Laios AH, Montalto S, Mehra G, Spencer J, Ahmed AA, Raju-Kankipati S, Taams LS, Diebold SS. Interleukin-10 and prostaglandin E2 have complementary but distinct suppressive effects on toll-like receptor-mediated dendritic cell activation in ovarian carcinoma. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0175712. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lamichhane P, Karyampudi L, Shreeder B, Krempski J, Bahr D, Daum J, Kalli KR, Goode EL, Block MS, Cannon MJ, Knutson KL. IL10 release upon PD-1 blockade sustains immunosuppression in ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2017;77:6667–6678. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sieg DJ, Hauck CR, Ilic D, Klingbeil CK, Schaefer E, Damsky CH, Schlaepfer DD. FAK integrates growth-factor and integrin signals to promote cell migration. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:249–256. doi: 10.1038/35010517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lane D, Matte I, Laplante C, Garde-Granger P, Carignan A, Bessette P, Rancourt C, Piché A. CCL18 from ascites promotes ovarian cancer cell migration through proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2 signaling. Mol Cancer. 2016;15:58. doi: 10.1186/s12943-016-0542-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu L, Deng Z, Peng Y, Han L, Liu J, Wang L, Li B, Zhao J, Jiao S, Wei H. Ascites-derived IL-6 and IL-10 synergistically expand CD14+HLA-DR−/low myeloid-derived suppressor cells in ovarian cancer patients. Oncotarget. 2017;8:76843–76856. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kohno T, Mizukami H, Suzuki M, Saga Y, Takei Y, Shimpo M, Matsushita T, Okada T, Hanazono Y, Kume A, Sato I, Ozawa K. Interleukin-10-mediated inhibition of angiogenesis and tumor growth in mice bearing VEGF-producing ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5091–5094. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deying W, Feng G, Shumei L, Hui Z, Ming L, Hongqing W. CAF-derived HGF promotes cell proliferation and drug resistance by up-regulating the c-met/PI3K/Akt and GRP78 signalling in ovarian cancer cells. Biosci Rep. 2017;37:BSR20160470. doi: 10.1042/BSR20160470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goldsmith ZG, Ha JH, Jayaraman M, Dhanasekaran DN. Lysophosphatidic acid stimulates the proliferation of ovarian Cancer cells via the gep proto-oncogene Gα(12) Genes Cancer. 2011;2:563–575. doi: 10.1177/1947601911419362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang Y, Li L, Guo X, Jin X, Sun W, Zhang X, Xu RC. Interleukin-6 signaling regulates anchorage-independent growth, proliferation, adhesion and invasion in human ovarian cancer cells. Cytokine. 2012;59:228–236. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2012.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yousif NG. Fibronectin promotes migration and invasion of ovarian cancer cells through up-regulation of FAK-PI3K/Akt pathway. Cell Biol Int. 2014;38:85–91. doi: 10.1002/cbin.10184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bian D, Su S, Mahanivong C, Cheng RK, Han Q, Pan ZK, Sun P, Huang S. Lysophosphatidic acid stimulates ovarian cancer cell migration via a Ras-MEK kinase 1 pathway. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4209–4217. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lo CW, Chen MW, Hsiao M, Wang S, Chen CA, Hsiao SM, Chang JS, Lai TC, Rose-John S, Kuo ML, Wei LH. IL-6 trans-signaling in formation and progression of malignant ascites in ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71:424–434. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Furukama S, Soeda S, Kiko Y, Suzuki O, Hashimoto Y, Watanabe T, Nishiyama H, Tasaki K, Hojo H, Abe M, Fujimori K. MCP-1 promotes invasion and adhesion of human ovarian cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:4785–4790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sung WW, Wang YC, Lin PL, Cheng YW, Chen CY, Wu TC, Lee H. IL-10 promotes tumor aggressiveness via upregulation of CIP2A transcription in lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 2013;19:4092–4103. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen XD, Tang SX, Zhang JH, Zhang LT, Wang YW. CIP2A, an oncoprotein, is associated with cell proliferation, invasion and migration in laryngeal carcinoma cells. Oncol Rep. 2017;38:1005–1012. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.5759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sabat R, Grutz G, Warszawska K, Kirsch S, Witte E, Wolk K, Geginat J. Biology of interleukin-10. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2010;21:331–344. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kipps E, Tan DS, Kaye SB. Meeting the challenge of ascites in ovarian cancer: new avenues for therapy and research. Nat Rev. 2013;13:273–282. doi: 10.1038/nrc3432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rabinovich A, Medina L, Piura B, Huleihel M. Expression of IL-10 in human normal and cancerous ovarian tissues and cells. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2010;21:122–128. doi: 10.1684/ecn.2010.0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yao V, Platell C, Hall JC. Peritoneal mesothelial cells produce inflammatory related cytokines. ANZ J Surg. 2004;74:997–1002. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-1433.2004.03220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alldredge J, Flies D, Higuchi T, Ma T, Adams SF. Impaired interleukin-10 signaling and ovarian cancer growth in the peritoneal cavity. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(15 suppl):e22094–e22094. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PPT 265 kb)