Abstract

This study was conducted to examine differences between self- and proxy ratings of activities in daily living (ADL) in nursing home residents and to compare them with actual performance. An impact of cognitive status on these ratings was also determined. Data were obtained from 164 dyads of nursing home residents (self-ratings) and their professional care providers (proxy ratings). Statistical procedures included t tests, intraclass correlations, Pearson’s correlations, analysis of variance (ANOVA) and ROC curves. Paired t test provided evidence that residents in general overestimated their abilities for all ADLs (p < .01 in all cases), but a substantial subset of 54 residents, with mean MMSE of 18, agreed with their care providers. The mean MMSE score of those who overestimated their abilities was 13 (N = 57). The ANOVA revealed that greater rating differences were associated with more severe cognitive impairment (MMSE, F = 9.93, p < .001). Proxy ratings of walking were not significantly different from actual performances (p = .145), while self-ratings overestimated it (p < .001). Although residents in general overestimated their ADL abilities and results of comparison with actual performance indicated that proxies may be closer to the actual status in this population, a considerable number of those with milder cognitive impairment were able to assess their ADLs with reasonable accuracy.

Keywords: Nursing home residents, ADL, Self-reports, Proxy reports, Agreement, Differences

Introduction

Nursing home residents are a vulnerable population, often characterized by multiple comorbidities, cognitive deficits and some degree of dependence in activities of daily living (ADLs) (Gerstenecker et al. 2014; Hofmann and Hahn 2014). The provision of appropriate and person-centered care requires, among other things, comprehensive knowledge of residents’ individual residual physical functioning (Valk et al. 2001). Especially important is the evaluation of ADLs which can help to understand functional limitations or service needs (Morris et al. 1990; Onder et al. 2012). In addition, evaluation of ADLs is an important part of complex geriatric assessment (Jiang and Li 2016).

Commonly used instruments to measure ADL functioning in nursing home residents are based on the opinion of caregivers (Morris et al. 2009; Mahoney and Barthel 1965) or trained observers (Katz et al. 1963), and the residents’ perception of their ADL functioning is often neglected. The employment of self-reports might provide deeper insight into residents’ functional abilities, enable us to better understand residents’ needs and limitations and provide residents with an opportunity to actively participate. Furthermore, self-reports are essential in pursuit of high-quality and patient-centered care (Koren 2010; Mast 2012). But can we trust self-reports provided by frail older adults often with cognitive limitations? What are the differences between self- and proxy reports in nursing home residents and who is closer to actual performance?

Although results of previous research indicated that there is in general good agreement between self- and other external ratings when assessing more objective constructs such as physical functioning (Snow et al. 2005), significant differences were detected in some populations of older adults (Li, Harris and Lu 2015; Magaziner et al. 1996; Rubenstein et al. 1984). Individuals with cognitive deficits have demonstrated a tendency to overestimate their functional abilities (Farias et al. 2005; Miller et al. 2013; Ostbye et al. 1997; Weinberger et al. 1992; Kiyak et al. 1994). Nevertheless, the results of available studies are not always uniform. For instance, Farrow and Samet (1990) did not find cognitive status to be related to respondents’ bias, and Santos-Eggimann et al. (1999) found that proxy raters reported only slightly higher estimates of dependence. It is important to note that none of the cited research was conducted in long-term care settings.

The present study was conducted in a long-term care setting and is also unique because of the usage of a performance-based test, which is still rather rare in nursing homes research, despite the decreased bias and increased accuracy and sensitivity associated with performance-based tests in this population (Cress et al. 2008; Puente et al. 2014; Binder et al. 2001). Performance-based tests rely on direct observation of tasks and thus avoid most of the problematic issues typical for both self- and proxy reports. We decided to use walking for the comparison of the two reports with actual performance for several reasons. First of all walking is a very basic and at the same time very complex movement that is familiar to all older adults and that provides great deal of information about the tested persons. Walking ability is considered to be one of the strongest predictors of adverse health outcomes in elderly population (Cesari et al. 2005; Gill et al. 1995). Also it is a simple and well-developed construct to assess (Schwenk et al. 2014). The employment of performance-based tests could help to improve the understanding of differences between self- and proxy reports of physical functioning. We have identified one study that compared the results of both self- and proxy ratings of physical functioning (ADL and IADL) with actual performance in community dwelling older adults (Puente et al. 2014). Authors concluded that ratings of older adults with mild cognitive impairment are consistent with ratings of proxies and that the potential deficits in physical functioning are more likely to be detected by performance-based testing in this population. Results of a study comparing a self-reported and a performance-based assessment of mobility found the two approaches to be roughly concordant in Hispanic elderly (Angel et al. 2000). Studies conducted by Cotter et al. (2002) and Loewenstein et al. (2001) compared proxy reports of ADLs with direct observation of dementia patients’ performance of ADLs and concluded that caregivers of dementia patients can assess patients’ ADL with reasonable accuracy. However, the literature is rather sparse and there is a complete lack of research in nursing home residents.

The present study fills the gap and provides deeper insight into the usability of self-reports in long-term care settings. It extends the understanding in this area by examining three different commonly used approaches to measure physical functioning, defined as ability to perform ADLs, in nursing home residents, and to evaluate the effect of cognitive status. The aims of the study were as follows: (a) to examine the differences between self- and proxy reports of ADLs in nursing home residents, (b) to determine the impact of cognitive status on expected differences and (c) to compare both self- and proxy reports with actual performance. To address the last aim, only one item of the ADL battery (Walking) was used. Our intent was to provide evidence that many nursing home residents are able to provide reliable and meaningful reports of their physical functioning and to support the inclusion of nursing home residents into the assessment process. But at the same time we wanted to caution about a blind trust to self-reports of those with more severe cognitive limitation which is unfortunately the issue in the Czech Republic.

Methods

Participants

Participants were residents of two nursing homes in the Czech Republic that took part in the project long-term care for seniors: quality of care in institutions, organization’s culture and support of frail older persons (NT11325) funded by the Internal Grant Agency of the Ministry of Health. The selection of the two nursing homes was based on convenience. The two nursing homes have a capacity to provide continuous care for 183 residents with special needs (91 and 92). The care is provided by approximately 30 carers and 10 nurses in each nursing home. The intention was to collect data from all available residents regardless of the health status. A total of 19 residents were either receiving acute care or were not present at the time of data collection, or just did not agree to participate. Thus, this study included 164 dyads of older adults and their professional care providers, represented by head nurses from each nursing home, who were responsible for the proxy ratings. Both head nurses consulted their responses with a team member that directly cared for the patient in question. Remaining data were collected by trained research assistants, and sociodemographic characteristics were obtained from the medical records of the nursing homes. Despite the best efforts of our test administrators as well as care providers, some data were missing due to an occasional refusal of participants to cooperate. The tables include detailed information about available data for each variable or analysis. The Ethical Committee and Institutional Review Board at the Internal Grant Agency of the Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic approved this study. Informed consent was obtained from each study participant or their legal representative, if necessary.

Measures and procedure

Descriptive variables included sociodemographic characteristics such as age, gender and education. Health-related variables included cognitive status assessed by the mini-mental state examination (MMSE) (Folstein et al. 1975) and mental health assessed by a short version of the Geriatric Depression Scale—GDS 15 (Sheikh and Yesavage 1986), translated into the Czech language and standardized for use in the Czech Republic (Jirak 2004).

Outcome measures included activities of daily living (ADLs) assessed by nursing home residents and their care providers (self- and proxy ratings) with a closer attention to one of the ADL items addressing walking ability (Walking) which was also assessed by direct measurement of walking performance.

Activities of daily living (ADLs) were assessed using the interRAI Long-Term Care Facilities Assessment System (InterRAI LTCF) which is a comprehensive, standardized instrument for evaluating the needs, strengths and preferences of persons in long-term care and in nursing home institutional settings (Morris et al. 2009). This instrument evaluates the person’s self-care performance in ADLs for three consecutive days. The ten activities (bathing, personal hygiene, dressing upper body, dressing lower body, walking, locomotion, transfer toilet, toilet use, bed mobility and eating) were assessed on the scale 0–6 (0 = independent, 1 = independent, setup help only—verbal guidance, 2 = supervision, 3 = limited assistance, 4 = extensive assistance, 5 = maximal assistance and 6 = total dependence) resulting in the range of total scores from 0 to 60 (lower scores = better ability). Each activity was independently assessed by the nursing home resident (self-ratings) as well as by his/her care provider (proxy ratings).

Walking performance was assessed by a part of the get up-and-go test (Mathias et al. 1986) adapted and standardized for use in the Czech Republic (Holmerova et al. 2003). The full test starts in a sitting position in a straight-backed chair and with the participant asked to perform five tasks: to get up, to walk forward 3 m, to turn around a cone, walk back to the chair, turn and to sit again. Each task is evaluated with a score ranging from 0 to 3 (0 = cannot perform; 1 = performs with a help of other person (significant instability); 2 = performs using an assistive device or the walk is groggy; 3 = performs without any problems), resulting in a total score ranging from 0 to 12. However, for the purpose of the present study, only evaluation of the second task (3-m walk) with scores 0–3 was used.

Self-ratings of walking by nursing home residents and proxy ratings of walking by care providers were assessed using the Walking item from the interRAI LTCF instrument and, at the stage of data analysis, recoded according to walking performance assessment into a 3-point scale to enable comparability with direct walking assessment. The original code 0 (independent—no physical assistance, setup or supervision in any episode) was recoded to 3; code 1 (independent, setup help only—article of device provided or placed within reach, no physical assistance or supervision in any episode) and code 2 (supervision—oversight/cuing) were recoded to 2; code 3 (limited assistance—guided maneuvering of limbs, physical guidance without taking weight) and code 4 (extensive assistance—weight-bearing support by one helper where person still performs 50% or more of subtask) were recorded to 1; and finally code 5 (maximal assistance—weight-bearing support by 2 or more helpers or weight-bearing support for more than 50% subtask) and code 6 (total dependence—full performance by others during all episodes) were recoded to 0.

Data analysis

Statistical Package for Social Sciences (IBM SPSS statistics 22 for Windows) was used to analyze all data. Basic descriptive statistics was used to characterize the study sample. Pearson’s correlation was used to analyze possible associations between outcome measures. Paired-samples t tests were used to detect possible systematic differences between the ADL ratings (self- and proxy ratings). Correlation coefficients accompanied by a scatter plot were used to define association between the expected rating differences and cognitive status. ANOVA for repeated measures with LSD post hoc tests was used to further investigate the relationship between the difference of ADL ratings and cognitive status and to test differences between the three approaches to measure walking ability. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were used to compare sensitivity versus specificity of self- and proxy ratings of walking, for the ability to predict an agreement with actual performance. And finally, 2-way mixed intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) for absolute agreement were used to test the strength of agreement between nursing home residents and their care providers on the ADL sum as well as on individual items and between the three walking assessments. An ICC over 0.70 was considered as excellent agreement, ICC between 0.40 and 0.70 was considered as good agreement, and ICC below 0.40 was considered as poor agreement (Nunnally and Bernestein 1994). Parametric tests were preferred over nonparametric because of the size of our sample which may compensate violation to normality assumption and data type (Tiku 1971; Kirk 1995; Norman and Streiner 2008). On the other hand, nonparametric tests imply significant disadvantages such as the loss in precision (Edgington 1995) or loss of power (Tanizaki 1997) as compared to parametric tests. Statistical significance (p) was assessed at a two-tailed .05 level.

Results

Basic characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. The mean age of residents was over 83 years, and the majority of the sample was females. More than half of the participants were widowed, and exactly half of them had just basic education (5–9 years). The mean MMSE score was 13.1 and mean GDS score was 5.4.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participating residents (demographics and, basic functional status)

| Sample characteristics | N (%) or mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Gender (N = 164), female | 141 (86.0%) |

| Age (N = 164) | 83.3 (7.1) |

| Marital status (N = 150) | |

| Single | 23 (14.0%) |

| Married | 22 (13.4%) |

| Widow/widower | 100 (61.0%) |

| Divorced or separated | 5 (3.0%) |

| Education (N = 145) | |

| 5–9 years | 82 (50.0%) |

| 10–12 years | 22 (13.4%) |

| Over 12 years | 41 (25.0%) |

| GDS (0–15) (N = 121) | 5.4 (3.2) |

| MMSE (0–30) (N = 143) | 13.1 (8.6) |

Self- versus proxy ADL ratings (ADL sum and individual items)

Comparison of mean self- and proxy ratings of ADLs is presented in Table 2. ADL sum mean self-ratings suggested more independence (16.6) when compared to ratings of proxies (26.5). All self–proxy differences, including ADL sum, were statistically significant (p < .001 or p < .01), suggesting that, in general, nursing home residents significantly overestimated their functional abilities. The overestimation was smallest in eating and highest in dressing upper body. In addition, high overestimation was also observed in dressing lower body, bathing, transfer toilet and toilet use. Intraclass correlation coefficient values ranged from 0.37 (bathing) to 0.87 (Walking). Intraclass correlations for all of ADL items except for bathing were considered good, whereas intraclass correlations of walking and locomotion were excellent, suggesting good average agreement between the two groups of raters.

Table 2.

Comparison of mean self- and proxy ADL (overall and individual items) differences

| Self-assessment, mean (SD) | Proxy assessment, mean (SD) | Self-proxy difference | t | P | ICC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADL sum (N = 115) | 16.6 (14.7) | 26.5 (18.4) | − 9.89 | − 6.89 | < .001 | 0.66 |

| Bathing (N = 121) | 3.4 (1.8) | 4.7 (1.2) | − 1.25 | − 7.63 | < .001 | 0.37 |

| Personal hygiene (N = 118) | 1.1 (1.7) | 2.2 (2.2) | − 1.10 | − 5.49 | < .001 | 0.51 |

| Dressing upper body (N = 117) | 1.4 (1.9) | 2.7 (2.4) | − 1.33 | − 6.58 | < .001 | 0.59 |

| Dressing lower body (N = 115) | 2.0 (2.3) | 3.2 (2.4) | − 1.24 | − 5.97 | < .001 | 0.65 |

| Walking (N = 119) | 2.6 (2.6) | 3.2 (2.7) | − 0.60 | − 3.71 | < .001 | 0.87 |

| Locomotion (N = 118) | 1.9 (2.4) | 2.7 (2.7) | − 0.74 | − 4.28 | < .001 | 0.83 |

| Transfer toilet (N = 116) | 1.4 (2.2) | 2.9 (2.6) | − 1.27 | − 6.01 | < .001 | 0.67 |

| Toilet use (N = 115) | 1.7 (2.2) | 2.9 (2.5) | − 1.22 | − 6.15 | < .001 | 0.69 |

| Bed mobility (N = 119) | 0.6 (1.3) | 1.2 (2.0) | − 0.65 | − 3.72 | < .001 | 0.50 |

| Eating (N = 120) | 0.5 (1.1) | 0.9 (1.7) | − 0.43 | − 2.97 | < .01 | 0.55 |

Differences in ADL ratings and its association with cognitive status

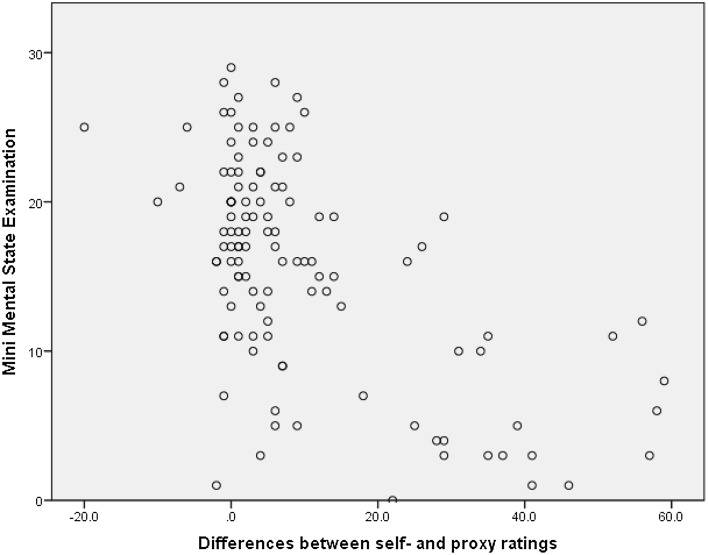

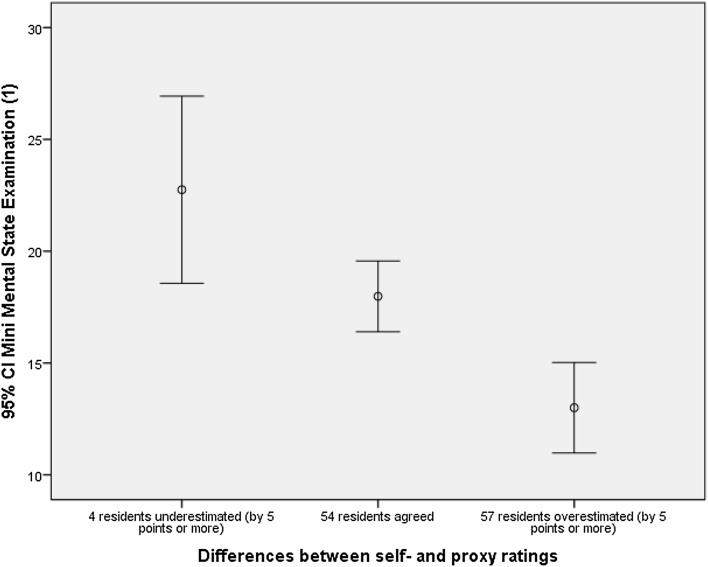

The degree of differences between self- and proxy ratings of ADL sums was significantly correlated with MMSE scores (r = − .67, p < .01). The character of this association was expressed by a scatter plot (Fig. 1). Other available characteristics, including GDS and demographics, were not correlated significantly with rating differences. In order to provide clinically meaningful results and also to further investigate the identified association between cognitive status and the differences between self- and proxy ADL, the participants were divided according to the degree of the difference in ADL sum ratings. Our data showed that almost all subjects’ rating of their sum ADLs was either very close to proxy ratings or the scores were lower. When we divided the subjects into two groups of similar size, one group’s scores were within ± 5 points of proxy ratings and the other group was more than 5 points lower. Using the 5 points as a reference, there were also few subjects whose self-ratings were more than 5 points higher than proxy ratings. Thus, we divided subjects of this study into three groups. The first group (Group 1, N = 4) represented nursing home residents who underestimated their overall ADL abilities as opposed to their care providers by 5 or more points, the second group (Group 2, N = 54) represented those nursing home residents who agreed with their care provider (within ± 4 points), and the third group (Group 3, N = 57) represented those nursing home residents who overestimated their overall ADL abilities by 5 or more points. The remaining residents (N = 28) were not able to assess their ADL abilities, so they were not included in this analysis.

Fig. 1.

Association between cognitive status (MMSE score) and self–proxy difference of the sum ADL score (N = 115)

An analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed that the MMSE score differed significantly across the three groups (F = 9.93, p < .001). It was found that the nursing home residents with higher MMSE score (mean score of 22.8, SD = 2.6) tended to underestimate their functional abilities (Group 1), whereas nursing home residents with lower MMSE (mean score of 13.0, SD = 7.6) tended to overestimate their functional abilities (Group 3). A mean MMSE score of 18.0 (SD = 5.8) was found in the group of nursing home residents who agreed with their care provider (Group 2). Follow-up post hoc comparison using the LSD test revealed that the mean MMSE score was significantly different between two out of the three groups (p < .001 or p < .01). Only Group 1 (nursing home residents who underestimated their functional abilities) and Group 2 (nursing home residents who agreed with care providers) did not differ significantly (p = .173) (Fig. 2). The mean MMSE score of residents who were not able to assess their ADLs was 2.3 (SD = 4.0). Such a low mean of MMSE was due to 15 residents who could not answer any MMSE item and, therefore, had a score of 0.

Fig. 2.

Association between cognitive status (MMSE score) and self–proxy difference of the sum ADL score defined by three groups (N = 115)

Comparison of self- and proxy ratings of walking with walking performance

Comparisons of both self- and proxy ratings of walking with walking performance (all variables on the scale 0–3, higher score better ability) are presented in Table 3. Mean self-rated walking was rather optimistic (1.6), while proxy-rated walking and actual walking performance identified more difficulties (1.4 and 1.2, respectively). Results of ANOVA for repeated measures were significant (F = 13. 386, p < .001), and the LSD post hoc test revealed that mean self-ratings of walking and walking performance differed significantly (p < .001) because on average, residents overestimated their abilities. Also the differences between self- and proxy ratings were significant (p < .01) and suggesting again residents’ overestimation. And finally, the proxy ratings of walking were not significantly different from actual walking performance (p = .145). Despite the mean differences, intraclass correlation coefficients indicated excellent agreement between raters in all cases (r = .81 for performance walking vs. proxy ratings of walking, r = .90 for performance walking vs. self-ratings of walking and r = .87 for self- vs. proxy ratings of walking). Comparison of areas under the ROC curves suggested that proxy ratings of walking have slightly better ability to predict actual performance than self-ratings of walking (areas = 0.82 vs. 0.75, p < .001).

Table 3.

Comparisons of the three approaches to measure walking ability (N = 113)

| Mean (SD) | ANOVA. F (sig.) | LSD post hoc test. sig. (groups) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Performance walking (1) | 1.2 (1.1) | 13.386 (p < .001) | p < .001 (1 vs. 2) |

| p = .145 (1 vs. 3) | |||

| Self-rated walking (2) | 1.6 (1.3) | p < .01 (2 vs. 3) | |

| Proxy-rated walking (3) | 1.4 (1.4) |

In attempt to examine the potential effect of cognitive status on the differences between self-ratings of walking and actual walking performance, we repeated similar procedures that we used for ADL sum scores. Although the correlation of the differences between walking performance scores and self-rated walking with MMSE scores was statistically significant (r = .21, p < .05), it was rather low. Nevertheless, we divided data into three groups based on the degree of the difference as follows: Group 1 (N = 42) represented those who overestimated their walking ability, Group 2 (N = 59) represented those were accurate, and Group 3 (N = 11) represented those who underestimated their walking ability as compared with actual walking performance. However, the result of ANOVA was not significant (F = 0.689, p = .504), indicating that the average MMSE scores were similar in all three groups.

Discussion

The general purpose of this study was to compare the results of three different approaches to assess physical functioning in nursing home residents—self-ratings, proxy ratings and performance-based observations, and to address the impact of cognitive status on the differences. Unfortunately, we have identified a severe misuse of different sources of data in the Czech Republic. For instance, only self-reports are used when deciding about care allowance regardless of the fact that potentially biased responses may have disastrous consequences for the person in question, because overestimation of functional abilities will decrease or eliminate their care allowance. On the other hand, older adults’ opinion is totally neglected in long-term care settings, which increases undesirable passivity of residents and contradicts the provision of high-quality and person-centered care. In addition, care providers using standardized instruments for long-term care setting may not accurately assess the maximum capacity of residents because of help provided by staff. At the end, they assess what residents are allowed to do, instead of able to do. We believe that similar issues might be relevant in other countries, but the research evidence is lacking.

Although there is research focused on the differences between self- and proxy ratings in both cognitively impaired and intact older adults, proxy ratings are provided mostly by informal caregivers, while our study used ratings of professionals. Moreover, only a few studies have so far investigated the differences between subjective judgments, either self- or proxy, and actual performance. And the most importantly, to our best knowledge, there is a significant lack of research conducted in long-term care settings. In agreement with available literature, our data suggest that proxy responses by professional care providers to a large extent conform with answers provided by nursing home residents but, in general, produce higher estimates of dependence (Neumann et al. 2000; Santos-Eggimann et al. 1999). The intraclass correlation indicating the level of agreement between the two groups of raters was considered generally good for the ADL sum score. Regarding the individual ADL items, the highest intraclass correlation was observed in ADL items walking and locomotion which is in line with what has been already reported (Ostbye et al. 1997), and lowest for bathing. It seems that the level of agreement is lower in more complex tasks such as bathing, personal hygiene or eating which might be more difficult to assess, as opposed to simple and straightforward tasks such as walking or locomotion, where the level of agreement was higher.

However, the intraclass correlation (ICC) assesses the reliability of ratings by comparing the variability of different ratings of the same subject to the total variation across all ratings and all subjects. It can be large only if the paired measurements are in good agreement, but it suffers from the same faults as ordinary correlation coefficients. The magnitude of the ICC can be manipulated by the choice of samples to split, and it says nothing about the magnitude of the paired differences. This is the reason why we employed the paired t test.

Results of paired t test revealed significant differences between mean self- and proxy ADL sum scores as well as in all individual items. This difference suggested that majority of the nursing home residents overestimated their overall abilities to perform ADLs as compared to their care providers. The same tendencies were observed elsewhere (Farias et al. 2005; Miller et al. 2013; Kiyak et al. 1994; Ostbye et al. 1997; Weinberger et al. 1992). Statistically significant differences of mean scores were found in all individual ADL items, suggesting the residents’ overestimation of abilities also in all of those tasks. In parallel with the individual results of agreement analyses, the greatest differences were found in more complex items such as bathing, dressing upper body, dressing lower body, transfer toilet or toilet use where care providers rated lower abilities and on the average suggested that limited assistance was provided. It is possible that residents did not perceive the full extent of provided support and thus rated themselves more favorably. On contrary, differences were smaller (but still statistically significant) in simple straightforward tasks such as walking and locomotion despite the need of limited assistance. Also smaller differences were found in complex tasks which did not require any assistance but only setup help. Those included bed mobility and eating. This may be suggesting that the level of differences between self- and proxy ratings depends to some degree on the complexity of assessed task as well as the level of needed assistance.

The level of rating differences may be affected by several factors such as personal characteristics of self- or proxy raters or the nature of the relationship between them. Regarding the characteristics of residents, the only one which was significantly associated with the level of differences between self- and proxy ratings was cognitive status defined by the mini-mental state examination (MMSE) score. Other potential characteristics such as gender, education or depression were not related to rating differences in our data. The impact of cognitive status has been previously established (Farias et al. 2005; Miller et al. 2013; Ostbye et al. 1997; Weinberger et al. 1992), and in agreement with results of those studies, our data indicate that nursing home residents with lower MMSE scores overestimate their abilities to perform ADL more heavily than residents with higher MMSE scores.

However, more detailed examination revealed that about half of the nursing home residents rated their ADLs similarly as their proxies. Their average MMSE score was 18. This is suggesting that even residents with relatively low MMSE score could provide accurate assessment of their ADL abilities. Such results are supported by the rather high ICCs, suggesting good agreement between the two groups of raters presented in Table 2. It seems that the overall differences between the ratings in whole sample were caused by great overestimation of ADL abilities by another half of nursing home residents with average MMSE score of 13. Although the general tendencies are supporting previous findings about the association between self- proxy differences and cognitive status, it is evident even older adults with quite low MMSE scores can assess their ADL abilities accurately. Nevertheless, it is obvious that the ratings of older adults who had cognitive limitations should be used with caution.

Also potentially interesting might be finding that four residents with higher MMSE score underestimated their ADL abilities in comparison with their proxies. Their mean MMSE score was 22.8 (SD = 2.6). However, it is not possible to draw any conclusions based on such a small sample size. We can only agree with Loewenstein et al. (2001) and assume that the nursing home residents with above-average cognitive ability might be perceived by their care providers as above average in other areas regardless of their actual capabilities.

To answer the question whose reports of functional status may be closer to the actual status, the reports of nursing home residents and their care providers were compared with results of direct observation of actual performance. To ensure direct comparability, the results of self- and proxy ratings had to be recoded. The number of categories was reduced from seven to four as described in “Methods” section. Researchers in this field dealt with comparability problems differently. For instance Loewenstein et al. (2001) and his colleagues dichotomized results of Direct Assessment of Functional Status (DAFS) based on previously empirically established cutoffs for functional impairment (Loewenstein and Rubert 1995). Similarly, Angel et al. (2008) compared a 3-point scale of self-report of walking with the time it took to complete a 10-feet-long walk with a dichotomous indicator distinguishing between those who could complete the walk, regardless of the time it took, and those who could not complete the walk. We decided to preserve as many categories as possible in order to avoid information loss.

The difference between mean self-ratings of walking and mean walking performance was statistically significant, while the difference between mean proxy ratings of walking and walking performance was very small and not statistically significant, which is suggesting that care providers are more accurate in assessment of physical functioning of nursing home residents. Also comparison of areas under the ROC curve suggested that care providers rated walking ability slightly more accurately. Similar results have been found in the past by Cotter et al. (2002) who found that in a sample of patients with dementia, caregiver-reported ADLs measured by functional independence measure (FIM) correlated with observation-derived FIM scores and the means were similar. Results of Loewenstein’s study (2001) indicated also that caregivers are extremely accurate in assessing the functional performance of patients with dementia.

The present study’s conclusions are tempered by several limitations. First, only two nursing homes participated in the project and the selection was not random. On the other hand, the majority of residents of those nursing homes were included. Second, the number of nursing home residents who underestimated their ADL abilities as compared to their care providers (Group 1) was too low to make any definite conclusions. Third, the results of self- and proxy ratings had to be recoded into fewer categories in order to compare them with performance observation. However, some authors reduced the number of categories even more radically (Loewenstein et al. 2001; Angel et al. 2000). Fourth, to ensure direct comparability of self- and proxy reports with actual performance, only one ADL item was selected. We believe that the selected item may be considered the most comprehensive and representative of functional status (Cesari et al. 2005). And finally, we would like to point out that despite the best efforts of our test administrators, some data were missing due to occasional refusal of participants to cooperate. Provided tables include detailed information about available data for each variable or analysis.

In conclusion, our results indicate that nursing home residents in general tended to overestimate their abilities to perform ADL and that the level of the difference between self- and proxy ratings was associated with cognitive status. However, closer examination revealed that even residents with considerable cognitive deficits could evaluate their abilities with reasonable accuracy and thus that it is meaningful to include them in the assessment process. On the other hand, residents with higher MMSE scores tended to underestimate their ADL functioning. This underestimation was unexpected and requires further investigation. The comparison of the self- and proxy reports with actual performance offered evidence that the care providers are in general more accurate in assessing the physical functioning than the residents. These results have important implications for professionals working in nursing homes who need detailed understanding of the functional status of the residents to detect hidden or oncoming health problems, or just to strengthen the relationship between care providers and residents. Also our results might be beneficial for case-management approaches and for provision of high-quality and person-centered care.

Acknowledgements

This publication was supported by the Grant 15-32942A-P09 AZV of the Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Responsible editor: D.J.H. Deeg.

References

- Angel RJ, Ostir GV, Frisco ML, Markides KS. Comparison of self-reported and a performance-based assessment of mobility in the Hispanic Established Population for Epidemiological Studies of the Elderly. Res Aging. 2000;22(6):715–737. doi: 10.1177/0164027500226006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Angel RJ, Angel JL, Hill TD. A comparison of the health of older Hispanics in the United States and Mexico: methodological challenges. J Aging Health. 2008;20(1):3–31. doi: 10.1177/0898264307309924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder EF, Miller JP, Ball LJ. Development of a test of physical performance for the nursing home setting. Gerontologist. 2001;41(5):671–679. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.5.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesari M, Kritchevsky SB, Penninx BW, Nicklas BJ, Simonsick EM, Newman AB, Tylavsky FA, Brach JS, Satterfield S, Bauer DC, Visser M, Rubin SM, Harris TB, Pahor M. Prognostic value of usual gait speed in well-functioning older people—results from the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1675–1680. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotter EM, Burgio LD, Stevens AB, Roth DL, Gitlin LN. Correspondence of the functional independence measure (FIM) self-care subscale with real-time observations of dementia patients’ ADL performance in the home. Clin Rehabil. 2002;16(1):36–45. doi: 10.1191/0269215502cr465oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cress ME, Ferrucci L, Studenski S, Guralnik JM, Fried LP, Gill TM, Espeland MA, Nayfield S, Romanshkin S, Eldadah B. Functional outcomes for clinical trials in frail older persons: time to be moving. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(2):160–164. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.2.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgington ES. Randomization tests. New York: M. Dekker; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Farias ST, Mungas D, Jagust W. Degree of discrepancy between self and other-reported everyday functioning by cognitive status: dementia, mild cognitive impairment, and healthy elders. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20(9):827–834. doi: 10.1002/gps.1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrow DC, Samet JM. Comparability of information provided by elderly cancer patients and surrogates regarding health and functional status, social network, and life events. Epidemiology. 1990;1(5):370–376. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199009000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstenecker A, Mast BT, Shah S, Meeks S. Tracking the cognition of nursing home residents. Clin Gerontol. 2014;37:286–297. doi: 10.1080/07317115.2014.885921. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gill TM, Williams CS, Tinetti ME. Assessing risk for the onset of functional dependence among older adults: the role of physical performance. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43:603–609. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb07192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann H, Hahn S. Characteristics of nursing home residents and physical restraint: a systematic literature review. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(21–22):3012–3024. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmerova I, Juraskova B, Zikmundova K. Vybrane kapitoly z gerontologie. Praha: Cas; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S, Li P. Current development in elderly comprehensive assessment and research methods. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:3528248. doi: 10.1155/2016/3528248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jirak R. Evaluation of psychological functioning in the elderly. In: Kalvach Z, Zadak Z, Jirak R, editors. Geriatrics and gerontology. Prague: Grada Publishing; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185:914–919. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk RE. Experimental design: procedures for the behavioral sciences. 3. Pacific Grove: Brooks/Cole; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kiyak HA, Teri L, Borson S. Physical and functional health assessment in normal aging and in Alzheimer’s disease: self-reports vs family reports. Gerontologist. 1994;34(3):324–330. doi: 10.1093/geront/34.3.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koren MJ. Person-centered care for nursing home residents: the culture-change movement. Health Aff. 2010;29(2):312–317. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Harris I, Lu ZK. Differences in proxy-reported and patient-reported outcomes: assessing health and functional status among medicare beneficiaries. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2015;15:62. doi: 10.1186/s12874-015-0053-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein DA, Rubert MP. Staging functional impairment in dementia using performance based measures: a preliminary analysis. J Ment Health Aging. 1995;1:47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein DA, Arguelles S, Bravo M, Freeman RQ, Arguelles T, Acevedo A, Eisdorfer C. Caregivers’ judgments of the functional abilities of the Alzheimer’s disease patient: a comparison of proxy reports and objective measures. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2001;56(2):P78–P84. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.2.P78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magaziner J, Bassett SS, Hebel JR, Gruber-Baldini A. Use of proxies to measure health and functional status in epidemiologic studies of community-dwelling women aged 65 years and older. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;143(3):283–292. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the Barthel Index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mast BT. Methods for assessing the person with Alzheimer’s disease: integrating person-centered and diagnostic approaches to assessment. Clin Gerontol. 2012;35:360–375. doi: 10.1080/07317115.2012.702647. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mathias S, Nayak US, Isaacs B. Balance in elderly patients: the “get-up and go” test. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1986;67(6):387–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LS, Brown CL, Mitchell MB, Williamson GM. Activities of daily living are associated with older adult cognitive status: caregiver versus self-reports. J Appl Gerontol. 2013;32(1):3–30. doi: 10.1177/0733464811405495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JN, Hawes C, Fries BE, Phillips CD, Mor V, Katz S, Murphy K, Drugovich ML, Friedlob AS. Designing the national resident assessment instrument for nursing homes. Gerontologist. 1990;30(3):293–307. doi: 10.1093/geront/30.3.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JN, Belleville-Taylor P, Fries BE, Hawes C, Murphy K, Mor V, Nonemaker S, Phillips CD, Berg K, Bjorkgren M, et al. interRAI long-term care facilities (LTCF) assessment form and user’s manual. Version 9.1. Washington: interRAI; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Neumann PJ, Araki SS, Gutterman EM. The use of proxy respondents in studies of older adults: lessons, challenges, and opportunities. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(12):1646–1654. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman GR, Streiner DL. Biostatistics: the bare essentials. Hamilton: Bc Decker; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally JC, Bernestein IH. Psychometric theory. New York: McGraw-Hill Inc; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Onder G, Carpenter I, Finne-Soveri H, Gindin J, Frijters D, Henrard JC, Nikolaus T, Topinkova E, Tosato M, Liperoti R, et al. Assessment of nursing home residents in Europe: the services and health for elderly in long term care (SHELTER) study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:5. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostbye T, Tyas S, McDowell I, Koval J. Reported activities of daily living: agreement between elderly subjects with and without dementia and their caregivers. Age Ageing. 1997;26(2):99–106. doi: 10.1093/ageing/26.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puente AN, Terry DP, Faraco CC, Brown CL, Miller LS. Functional impairment in mild cognitive impairment evidenced using performance-based measurement. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2014;27(4):253–258. doi: 10.1177/0891988714532016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein LZ, Schairer C, Wieland GD, Kane R. Systematic biases in functional status assessment of elderly adults: effects of different data sources. J Gerontol. 1984;39(6):686–691. doi: 10.1093/geronj/39.6.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Eggimann B, Zobel F, Berod AC. Functional status of elderly home care users: do subjects, informal and professional caregivers agree? J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52(3):181–186. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00155-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwenk M, Howe C, Saleh A, Mohler J, Grewal G, Armstrong D, Najafi B. Frailty and technology: a systematic review of gait analysis in those with frailty. Gerontology. 2014;60:79–89. doi: 10.1159/000354211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh J, Yesavage J. Geriatric Depression Scale: recent findings and development of a short version. In: Brink TL, editor. Clinical gerontology: a guide to assessment and intervention. New York: Howarth Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Snow AL, Cook KF, Lin PS, Morgan RO, Magaziner J. Proxies and other external raters: methodological considerations. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(5 Pt 2):1676–1693. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00447.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanizaki H. Power comparison of non-parametric tests: small-sample properties from Monte Carlo experiments. J Appl Stat. 1997;24:603–632. doi: 10.1080/02664769723576. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tiku ML. Power function of the F-test under non-normal situations journal of the American Statistical Association. J Am Stat Assoc. 1971;66(336):913–916. [Google Scholar]

- Valk M, Post MW, Cools HJ, Schrijvers GA. Measuring disability in nursing home residents: validity and reliability of a newly developed instrument. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2001;56(3):P187–P191. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.3.P187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger M, Samsa GP, Schmader K, Greenberg SM, Carr DB, Wildman DS. Comparing proxy and patients’ perceptions of patients’ functional status: results from an outpatient geriatric clinic. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40(6):585–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb02107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]