Abstract

Background

Health care remains unacceptably error prone. Recently, efforts to address this problem have included the patient and their family as partners with providers in harm prevention. Policymakers and clinicians have created patient safety strategies to encourage patient engagement, yet they have typically not included patient perspectives in their development or been comprehensively evaluated. We do not have a good understanding of “if” and “how” patients want involvement in patient safety during clinical interactions.

Objective

The objective of this study was to gain insight into patients’ perspectives about their knowledge, comfort level and behaviours in promoting their safety while receiving health care in hospital.

Methods

The study design was a descriptive, exploratory qualitative approach to inductively examine how adult patients in a community hospital describe health‐care safety and see their role in preventing error.

Results

The findings, which included participation of 30 patients and four family members, indicate that although there are shared themes that influence a patient's engagement in safety, beliefs about involvement and actions taken are varied. Five conceptual themes emerged from their narratives: Personal Capacity, Experiential Knowledge, Personal Character, Relationships and Meaning of Safety.

Discussion

These results will be used to develop and test a pragmatic, accessible tool to enable providers a way to collaborate with patients for determining their personal level and type of safety involvement.

Conclusion

The most ethical and responsible approach to health‐care safety is to consider every potential way for improvement. This study provides fundamental insights into the complexity of patient engagement in safety.

Keywords: community hospital, patient engagement, patient safety, qualitative study

1. INTRODUCTION

The potential for harm inherent in health care has the attention of stakeholders as never before. With this knowledge, there has been a proliferation of strategies and interventions designed to improve health‐care safety. One of the strongest endorsements for the involvement of patients and families in the attempts to prevent health‐care harm has come from the World Health Organization.1

Health‐care safety strategies for patient involvement have been developed in Canada (eg Canadian Patient Safety Institute2) and internationally. However, there is limited evaluation of the adherence to, and effectiveness of these strategies, with some authors noting the lack of patient perspective, or use of evidence, in their development.3 Further, we could not find studies about patients’ experiences of and perspectives on safety engagement across the continuum of care during hospitalization, only on certain episodic tasks. There are also no validated tools to determine engagement preference and assess patients’ involvement in safety while in hospital. An inductive exploration of patients’ and families’ perspectives about if and how they should be involved clinically in patient safety was required.

2. BACKGROUND

The involvement of patients as active participants in error prevention has gained momentum in the last several years, particularly with the launch of the World Health Organization's Patients for Patient Safety programme.4 These partnerships, including others such as Consumers Advancing Patient Safety 5 and Partnership for Patient Safety 6 in the United States (US), aim to promote the voice of patients in the safety movement. However, a limited number of investigators have studied what individuals believe about participating in patient safety, and specifically at the bedside.7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 In a study of 2078 randomly selected discharged adult patients from 11 Midwest hospitals in the US, 91% agreed that patients could help prevent errors.14 The finding from a systematic review of generally favourable attitudes among patients to participate in safety strategies12 is supported by others, notably opinions from patients who cite the importance of partnership and shared responsibility.13, 15, 16 These overall positive attitudes, however, are qualified by several factors. First, patients are less willing to participate in challenging health‐care providers’ behaviours, such as asking staff if they have washed their hands. Rather, patients’ preference is for more traditional fact‐gathering approaches that are perceived as less confrontational.8, 10, 12, 17 Similar results were reported in a study of 491 older adults who believed their role in safety was to passively follow instructions.11 Perception of self‐efficacy and belief in the effectiveness of a particular strategy appear to influence the likelihood of an individual's action.9 Secondly, health‐care providers’ encouragement appears to favourably influence patients’ reported willingness to engage in certain safety‐related behaviours8, 12, 17, 18 which mirrors patient participation in general.19 Additionally, although credible evidence is lacking, it is not well understood whether the setting influences an individual's perception of the role they can or should play, varying, as example, from primary to tertiary settings.11, 17

Investigators have detailed patients’ strategies to protect themselves, often undetected by health‐care providers.20 Taking a family member or friend to a health‐care appointment was frequently reported across primary and ambulatory settings and included having them act as an advocate.21, 22, 23 Protecting oneself was expressed by giving more information to the physician in primary care settings,22 questioning the name of an unfamiliar medication or a change in its colour while in hospital24 and considering their own sense of involvement and responsibility in home settings.25 Mothers’ sense of vigilance over their hospitalized children and the efforts taken to “…successfully safeguard”26 them is poignantly described.11, 27 The vigilance undertaken by family members of patients of minority cultural and language backgrounds is noted.28 Finally, reports of patients’ involvement in ameliorating errors lend a strong argument for their safety involvement.12, 29, 30, 31, 32

Overall, there are gaps and inconsistencies in the literature, which include how safety is perceived by patients depending on the settings and across populations, the actual (vs anticipated) actions patients feel most comfortable in performing and the effect of these actions. If there is encouragement that patients have a role at the bedside in ensuring their safety, more substantial evidence is needed to determine the most appropriate and beneficial strategies for their involvement that is based on patient and family insights, not provider‐driven.

3. METHODS

The overall objective for this study was to gain insight into patients’ perspectives about their knowledge, comfort level and behaviours in promoting or helping their safety while receiving health care in a Canadian hospital. The primary research question was: How do patients describe healthcare safety and what are their attitudes and beliefs about their role in promoting it while receiving care in a community hospital? To further elucidate patient perspectives about different aspects of safety engagement, secondary research questions included: What behaviours do patients report in ensuring their safety while receiving care in a community hospital? What enables and hinders patients’ involvement in ensuring their safety while receiving care in a community hospital? What information needs do patients report about ensuring their safety while receiving care in a community hospital? What activities do patients report are comfortable to do to ensure their safety while receiving care in a community hospital?

3.1. Research design

The study was approached from the interpretative paradigm with an emphasis on describing and understanding.33 The study design is descriptive exploratory and it is categorized as generic qualitative research, which is defined by Caelli et al34 as a qualitative endeavour without being shaped by one of the known methodologies.

3.2. Setting

The setting was a community hospital (52 beds) in Ontario, Canada. At the time of the study, this hospital had 24 medical/surgical beds, four special care beds (level 2 ICU), 22 complex continuing care beds, two palliative care beds and outpatient ambulatory clinics.

3.3. Participants

The participants were adult inpatients or outpatients receiving care at the study site. To be eligible, participants had to be (a) able to speak and read English; (b) 18 years of age or older; (c) able to provide consent; and (d) medically stable as determined by the health‐care providers. Further, for the inpatient group, those who participated must have spent at least one night in hospital prior to being interviewed and were soon to be discharged. The family members were included in the interview as desired by the participant, and their comments were incorporated into the transcripts and analyses.

3.4. Interview tools

The open‐ended questions developed and used to garner information from participants were based on professional knowledge and common sense. The topics for some questions were informed by existing patient safety strategies2, 35 and the study site's patient information booklet, as well as common clinical processes (eg administration of medications; diagnostic testing; and staff hand washing). The questions were written at a Flesch‐Kincaid grade level 5 to reduce the need for clarification and as part of best practice to facilitate patient understanding.36 The demographic questions included (a) age in years; (b) gender; (c) reason for admission; (d) length of hospitalization; (e) health status; (f) previous hospitalizations; and (g) previous personal experience with adverse events in health care. All the patient information was collected from the participants only.

3.5. Procedure

The associated university research ethics board and the study site granted ethics approval. In the inpatient units, the nurses helped identify any eligible patients. Once patients were identified, staff approached them with a recruitment brochure to inquire if they would be interested in meeting the researcher (LD). The interviews were audio‐recorded.

3.6. Data management and analysis

All the data were treated as confidential, and the master participant list was kept separate from the raw data. The audio‐recordings of each interview were transcribed verbatim. Code words were created for all proper nouns and kept in a separate code sheet.

Inductive content analysis was employed for analysing the patients’ narratives to identify prominent themes and patterns.37 This process involved a first and second cycle coding process, wherein transcripts were coded in the first phase, and the codes were categorized into larger groupings/themes in the second phase. The family members who joined the interviews were also given a “family” code name linked to the related participant, and their statements were analysed based on the content and coded accordingly. This permitted analyses of all content as appropriate, as well as tracking of whether data were provided by a participant or family member.

3.7. Trustworthiness

To ensure the integrity of this research, a Model of Trustworthiness was used and considered truth value (credibility), applicability (transferability), consistency (dependability) and neutrality (confirmability).38, 39 The techniques used to ensure credibility included considerable time with each participant, as well as with a number of participants, which spanned over many months. Participants were asked their opinions about new ideas mentioned by previous participants to ensure concepts were explored in‐depth as needed. Related to transferability, the participant and setting details, as well as the rich, descriptive data from the study findings are valuable information for making informed comparisons to other contexts. Dependability was assured by accuracy of transcripts and auditable data analyses. Additionally, interviewing continued until it was determined that there were no new general themes. Regarding confirmability, an audit was not conducted, however, records (eg raw data; process notes) were maintained for every phase of the study. The lead author (LD) who conducted the interviews reflected on biases and perspectives through journaling, as well as continually discussing any concerns or reflections with her co‐investigator.

4. FINDINGS

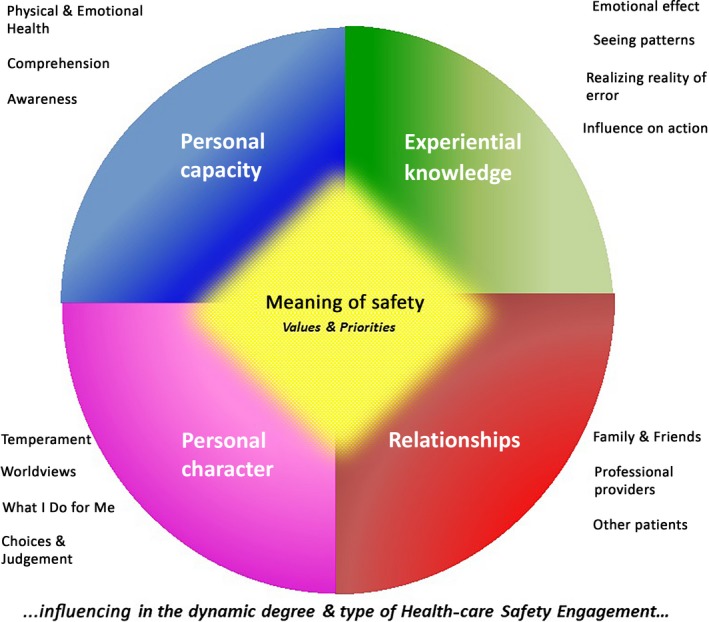

Fourteen women and 16 men (and four of their family members) were in this study, who ranged in age from 40 to 93 years old (average age 71 years old). Eleven individuals described a health‐care error(s) (personally or via a family member). All of the participants had had previous interaction with the health‐care system for different needs, and the reasons for their current admissions were varied, including but not limited to suffering a stroke; receiving care post‐surgery that was performed at another site (eg knee surgery); pneumonia; chest pain; bone fracture; cholecystectomy; bowel surgery; bleeding ulcer; cataract surgery; complications related to congestive heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. In describing their current and previous health‐care experiences, as well as targeted topics based on all the research questions, five main overarching themes (with subthemes) were identified: Personal Capacity; Experiential Knowledge; Personal Character; Relationships; and Meaning of Safety, and these were composed as a framework as defined by LoBiondo‐Wood et al.40 Collectively, all the themes are like the shards of coloured glass in a kaleidoscope—for each person, those facets are uniquely theirs, integrated and dynamic. Figure 1 is a visual representation of this 5‐Facet Framework for Patient Engagement in Patient Safety. The names used herein include pseudonyms and real names.

Figure 1.

5‐facet framework to describe patient engagement in patient safety

5. PERSONAL CAPACITY

5.1. Physical and emotional health

The participants talked about the severity of their illness/injury and of resulting limitations, as well as its evolution and influence on engagement. The participants who agreed with the premise of patient involvement in patient safety qualified it by saying that illness might preclude them from being engaged. Cindy, who was asked whether patients should be responsible for protecting their safety, said, to a certain point but I think that the hospital should be the ones that really look out for your best interests and protect you. She further reasoned:

When the person is sick they should be taken care of and kept safe and protected…because you've got enough worries yourself when you're sick, you're under enough strain and pressure worrying about what they're going to do and how things are going to turn out.

5.2. Comprehension

The participants identified that individuals will differ in their capacity to understand and to remember. This type of capacity can influence if and how engagement can occur. Mildred, admitted for fluid retention, was not certain of the cause, replying, I couldn't tell you because it's too many big words. Conversely, Henry, having had numerous hospitalizations, stopped the interview when he heard an alarm sounding that he could not discern, to check his oxygen saturation level. When asked if she thought patients should participate to ensure safety, Maria answered, to a certain extent, but qualified, I wonder how some people understand it.

5.3. Awareness

Observation and awareness of hospital processes differed between individuals. In discussing staff handwashing, Arthur admitted he did not know if they had, saying, Maybe they are, I'm just not noticing or paying attention. Arthur's mother added, I've seen them using that [hand sanitizer]. In another example, Arthur's mother mentioned the hospital's gown designed with a “wash your hands” reminder. He had not paid attention to it, while his mother had, saying, I thought that was a great idea—I notice things like that.

6. EXPERIENTIAL KNOWLEDGE

6.1. Emotional effect

In describing their experiences (eg typically related to an error), participants revealed varying emotions and talked about feeling anger, worry or having compassion. Most often experiences of health‐care error were in the past; however, the emotional intensity was still evident. Mildred vividly recalled her anger regarding a lapse in care.

My daughter went for a mammogram and they never sent her report to her doctor. By the time [daughter's name] went for her check‐up, the doctor said to her did you go for a mammogram and she said yes. She was in her fourth stage of breast cancer at that point. We were all very angry.

The participants also expressed empathy and understanding about error. Otis’ experience with his mother's medication error illustrated several concepts—the upset and difficulty of seeing a family member suffer because of an oversight; the anger expressed by his family; and the ultimate resolution and understanding that errors happen. He said,

I saw how she suffered and suffered trying to do dialysis [required due to the medication error]. It was not a nice thing to see a family member going through. It was human error. Some of my family was going to sue and my mother said no. This was a good doctor and it fell through the cracks.

Additionally, the participants gained confidence and comfort in attaining certain experiences, while unknown situations induced trepidation.

6.2. Seeing patterns

For some participants, their way of understanding the health‐care environment and what might be expected of them involved looking for routines or patterns and that was afforded by time spent in other clinical settings and or the current one. By understanding the patterns or processes, this allowed for a certain control and ability to act in a seemingly vulnerable and dependent position. Sue, having had a longer hospitalization, had come to experience a certain routine and when that changed one day, she tried to make sense of it. She said,

I notice things. Normally they take your vitals around twelve o'clock at night – they didn't last night. This morning I was up early because I heard [name] walking in the hall, and sat down and I kept thinking they usually take my vitals before they bring my meal and they didn't today.

Aidan had had a number of prior hospitalizations and, like many, had brought his medication list to the hospital. He explained his rationale saying, usually when I've been over before they ask me… so I always carry the medication list in my wallet.

6.3. Realizing the reality of error

Participants came to appreciate the reality of error by virtue of their experiences. Several articulated a realization of the potential for error that they had not grasped or had awareness of before their experience. Their experiences brought perspective that errors could happen to them. Barb matter‐of‐factly commented that, in light of her incident, it makes her [me] understand that doctors can make errors. Henry still grappled with the realization of his medication mistake. He related, this goes to show you that it can happen – I know humans all make mistakes, but in healthcare you've got to be extra careful.

6.4. Influence on action

The participants’ experiences had varying implication on their behaviour. Of the individuals who had experienced a health‐care error, some did not feel it had significantly altered anything, while others spoke of changes. When asked if past difficulties had changed her, Paula said,

It's not so much as I don't trust them, I will question. I didn't before – it was God's word. Because that was the way I was raised. Doctor was God. You did not dare question or ask, anything. Their word was absolute. Now I will ask. And I will take a notebook and I will write down so that I have a copy of what's been said.

Ron changed physicians after his misdiagnosis, and because of the error associated with his mother's care, Otis avoided taking medications despite their indication.

Regarding future health‐care interactions, individuals dichotomized between where they had had a positive experience, and a negative or unfamiliar one. Aidan thought he would be more observant and hesitant if he returned to the site where he had had difficulty with his care. He confirmed that unfamiliar settings which had not garnered his confidence would necessitate his keen awareness. Gene, having experienced an error elsewhere, had examined the study site's website [infection rates] prior to his admission—something he would do again if going to a new setting. His wife, based on the positive experience at the study site, felt that he would be more diligent and would address issues as needed at new sites. Given his combined experiences, she believed he would be a lot more capable and knowledgeable and say wait a minute [if concerned].

7. PERSONAL CHARACTER

7.1. Temperament

Individuals revealed their personalities, sometimes apologetic for certain traits, sometimes unabashedly admitting characteristics, and often aligned with how they approached health care. Russ believed he must abide by the instructions of the providers, saying, it's [health‐care system] out of my control – you've got to go with the flow, don't ask questions, just go do it. Dan said, I just come and go with the flow, and was comfortable relinquishing control. Others recognized in themselves a hesitancy to act for fear it upset or was disruptive to a provider. Mary had not asked a specific question, revealing I just don't like making waves of any kind. Wanda, however, identified her need to question more, a contrast to her husband's nature. Some were selective in what they wanted to know, while others were interested in everything.

7.2. Worldviews

The participants disclosed different beliefs and life philosophies, detailing how these were realized in their behaviours and interactions. The participants’ worldviews, although varied, were similar in the importance they held for each individual. Peter's tenacity and resolve to get better was fuelled by his belief that you have to be determined and have positive thinking. He remarked that, determination's the most important thing. Similarly, Mike's worldview was captured in his words, I always try to make it a positive experience, which included supporting staff and encouraging an optimistic outlook.

7.3. What I do for me

Participants described personal strategies they used for their hospitalization, and how they coped with perceived deficits by, as example, implementing tactics from home. These safety strategies were independent of provider requests and included requesting raised bedrails at night; using a walker or cane; and consistency in wearing slippers or shoes.

Participants spoke of independently seeking and reading information (eg on the Internet). One person noted he did a lot of research at home and here [hospital] using a mobile device to better understand his health and procedure. Sue, however, was sceptical of searching for medical information and was not a great believer in looking up things…because you can say I've got half of those things. Another participant was not entirely sure why he had not read the 22‐page booklet about his medical procedure; however, his mother, who had read it, offered that he was not one to sit and read.

Medication was seen as personal and more relevant to one's control. Individuals said they would not feel comfortable asking a provider about handwashing, despite safety implications, yet had no hesitation in clarifying medications. It was suggested that medications seems more personal to me [patient] and not to them [providers]—handwashing is different than asking them about something that I'm going to be taking. In receiving in‐hospital medications, their involvement included checking the medications in varying ways and degrees of consistency (eg “sometimes” vs “always”). Strategies included asking about the medications; visual assessment for familiar cues, such as the number and colour; and taking comfort in how one was feeling as determination that there was no problem. For those who placed complete reliance on provider processes, this was based on a belief that it was not a patient responsibility and/or was due to system limitations that left no other choice.

Several individuals commented they had not engaged in any safety strategies; however, examples were identified. Dan, self‐described as accepting and laidback about his care, ultimately revealed he did check his intravenous medication. Those who believed they had done nothing exceptional but were shown how their behaviours had enabled safe care, described their actions as automatic. Additionally, some discounted their strategies as tactics (eg having a family member present), if it had not resulted in a need for them to be used.

The participants revealed their thoughts about being actively involved in safety. Paula, having experienced health‐care error, was emphatic and pointedly stated: patients n‐e‐e‐d to be involved. Aidan was also firm and pragmatic, seeing the necessity that it has to work both ways for overall effectiveness, which was echoed in Kevin's words, safety is everybody's responsibility. Wanda, equally resolute, shared, if you're not mindful and cognizant of everything that's happening to you and around you, then you have no one to blame if someone doesn't look after you properly. She clarified that she did not intend for patients to be a doctor in training, nor that it diminished the trust she felt for providers, but she could see system vulnerabilities (staff working long hours; many people and things to remember). She said, you're the number one person that should be looking after yourself, you're your best protector.

There were individuals who believed in safety engagement in varying lesser degrees of agreement. They saw limitations precluding their absolute involvement or had a personal belief that their role in this context should be minimal. Further, engagement and the need to assume responsibility may change depending on the circumstance as judged by the patient. Gene said, it wasn't really necessary in this hospital but certainly in other hospitals it might be. Otis characterized it as only to help out, and only if one would like to be involved. There were participants who did not think that patients had a role in patient safety. Their reasons included feeling that nothing needed to change, and that the role health‐care providers had and their associated responsibilities were satisfactory—this was providers’ jobs.

7.4. Choices and judgements

The participants made choices and judgements while in hospital. As example, they made different judgements about asking providers if they washed their hands, something that is encouraged in patient safety strategies.2 For some who reported being unsure if a provider had washed their hands, they had chosen not to question it or trusted that it had been done. Other rationalizations included whether they felt they knew enough about how to help ensure they receive safe care. Some participants identified that they felt they knew what they needed. Arthur declared he did not need to know more than he did because it's supposed to be their [provider's] job. His benchmark was his work and if that required 100% accuracy, he reasoned that others could achieve it. Fred, however, conceded he likely did not know enough, but was not troubled given he had no concerns. For those who would like to know more about helping ensure safe care, some qualified it with: there comes a point where there's only so much information that you need to know and then the rest of it you don't.

8. RELATIONSHIPS

8.1. Family and friends

In differing ways, family members taught, encouraged, advocated for and challenged each other. They were the participant's support when they were too sick, unaware, distracted or uninterested. It is not, however, to say that participants always followed what they learned from family or friends. Maria and Arthur, who described their hesitancy in asking about handwashing, could reference others they knew who behaved differently. The shared experiences with family members could also influence a participant's understanding. Wanda recounted,

I was amazed at the things I learned [at daughter's prenatal classes], and it wasn't just about what happened to me, but about things that surrounded me…from that time on I became far more aware of how important I thought it was to know exactly what was going on.

When a participant's family member was present, one individual's perception was tested against another's, as well as the “checking in” with each other about the correct details of an issue or event. Additionally, there were times when a family member helped to re‐phrase a question if they thought the participant misinterpreted or did not understand. The families also seemed to have “a sense of knowing” how they needed to function and each other's roles. One gentleman counted on his family for guidance in health matters, saying, they know what to do for me, and equally his mother accepted that he relies on us to let him know what's going on. Further, family members enacted their own safety strategies. One individual explained, I feel that sometimes he [husband] doesn't always ask the questions I think he should, so I'll step in and ask them for him.

8.2. Professional providers

The participants commented on interactions with health‐care professionals, including their expectations of providers and their efforts to facilitate that relationship (eg such as through the use of humour). They defended health‐care providers [past or current] and protected that relationship, even if mistakes in care had been made. They made allowances for, as example, late medications or delayed call bell response, appreciating providers are busy. If something had not yet been discussed or arranged, they made assumptions and trusted it would be managed. The participants who identified a medical error often tried to minimize the event. Ross, who needed to be hospitalized for a past medication error, declared of the incident, that was just an isolated little case there, that was all. While Barb remained steadfast that her provider was a good doctor, the paradox of her description of the incident revealed deeper, conflicted feelings as she admitted, but I do feel like what my doctor missed was a bit major.

When participants described negative attributes about an interaction with a health‐care provider it often centred on how they were made to feel. One participant recounted a past experience at another site, revealing that while his doctor was amazing, he felt that the staff didn't really care one way or the other about you personally. His wife was able to contrast between the positive interactions at the study site vs her husband's past negative experience. She articulated:

I think that hands on attention [at study site] and the interest in how the patient was feeling – ‘are you worried’ and ‘everything's going to be alright’. It makes a huge difference—you're a person versus a case.

Sarah said of the providers, they seem to care about you – and when we feel that, we feel stronger because we feel more secure, safer.

The participants identified talking with, learning from and working with health‐care providers as safety strategies. The participants’ involvement included alerting staff if they noticed anything amiss; requesting a medication before a condition exacerbated; and talking with providers preoperatively about issues that they thought staff should know. One participant detailed tracking his intake and output to not only help staff, but to make sure that they weren't giving me too much medication. Ilah felt it important that providers should accept it [involvement].

8.3. Other patients

As participants described their experiences, they included roommates. They shared how roommates often helped each other, such as seeking medical help when one was in need. Peter, having fallen, acknowledged the good fortune that his roommate was nearby saying, lucky enough there was another gentleman in my room and he called for help. Ilah also spoke about a previous time when her roommate had acted on her behalf by yelling to get help.

9. MEANING OF SAFETY

9.1. Values and priorities

The participants had distinct viewpoints of safe care and what “feeling safe” meant. There were times when participants struggled to find the words, likening it more to an elusive “feeling” and something that they knew they received but could not articulate. Mobility and fall prevention, the environment, and insightful, attentive staff, figured prominently in their responses. While practical considerations were provided, more conceptual ideas of safe care were also described, as when Dan talked about it being fair and honest. Table 1 provides examples of the participants’ views about the important elements of safe care.

Table 1.

Examples of how individuals define safe care and feeling safe

| In the words of participants: what safe care and feeling safe is about & should be… |

|---|

Elusive, hard to describe…

|

Mobility & fall prevention…

|

Rushing feels unsafe…

|

Away from stress of roommate…

|

Infection control…

|

Teaching (or not)…

|

Everyone follows safety standard…

|

Environment…

|

Providers’ responsibility…

|

Not threatened…

|

Medication administration…

|

Insightful, reliable & attentive staff…

|

Effective communication…

|

Fair, honest, nice…

|

Being mistreated…

|

Alerting staff…

|

Everyone's role…

|

Multifaceted…

|

Common sense…

|

Small town‐feel…

|

Caring…

|

Reinforcement and reminders…

|

Being aware…

|

Rights…

|

The participants’ answers about safe care were centred on the providers and health system, and viewpoints on the importance of patient engagement were not foremost. The definition of safe care was not typically inclusive of a patient's role. They reflected on how things are done to them, as recipients of all that transpires around them (for better or for worse)—a dependency. The real or perceived limitations for their involvement, or the belief that anything aligned with health care was beyond their responsibility, necessitated having faith in others. As such, integral to their thinking about safe care was trust. Sarah's eloquent wording was at the core of what so many indirectly implied about the Meaning of Safety: we trust our nurses, we trust the doctors – we have to, they have the knowledge.

10. DISCUSSION

Given the complex intricacies of patient engagement in patient safety, it is not a straightforward issue; we cannot simply say patients should or should not be engaged as partners in their safety. The 5‐Facet Framework for Patient Engagement in Patient Safety developed from this study is a way to conceptualize the components one must consider when engaging patients in patient safety at the bedside. A particular facet (or facets) will loom larger and their influence be more significant for one patient than for another. This was seen in the way participants emphasized certain issues, as evidenced in the time they spent talking about them, reiterating them, and in the power of their speech. Unlike others (eg Carman et al41), engagement is not seen as being on a continuum, but rather as much more dynamic than linear. A number of elements could influence what engagement looked like for a patient at any given time. As example, previous exposure to clinical interactions and or experience with error did not necessarily equate to an individual believing or wanting to be engaged. It is with this in mind that we must approach the dialogue about and assessment of patient engagement in safety, and—given its potentially dynamic nature—with a regularity similar to taking a vital sign.

It was revealed that every individual described a safety‐related activity they engaged in, whether they realized it as such or not. This is supported by Martin et al,42 who found that participants did not always identify certain actions as being related to safety. Similarly, Pinto et al43 reported that patients indicated they would have taken action if something was wrong even without the study intervention. Bishop44 described patients taking notes or having an advocate present as a safeguard. Other investigators have also identified that patients and family members (ie parents of patients) act in ways to safeguard themselves or another.45, 46

The participants based decisions on advice from family members and relied on them to, as example, bring medications or help decipher health‐care information. For many, it seemed a purposeful strategy. In this way, the family member could act as a second safety check. The results of other studies support this finding, such as the research by Rainey et al47 of seven family members (and 13 patients) and their vigilance. Additionally, parents with a sick child described actions they take to safeguard the child, including advocating and constant surveillance.46 Collectively, this evidence suggests that patients, as well as family members, are engaged in safety in their own ways.

An unusual finding of this study was that, despite individuals believing patients need to be engaged in safety, most expressed comfort with their current knowledge and understanding of safety. Further, although some admitted they probably did not know enough, they were satisfied with what that they knew. It may be that participants had difficulty articulating what information they needed, similar to participants in the study by Martin et al.42

Safety is principally seen as the responsibility of providers. Martin et al42 reported that, of the 25 patients they interviewed, safety was regarded as the purview of the provider, while the participants in Walters’ study, said that it [safety] should not be a patient's obligation.48 The participants in this study identified limitations to having an equal partnership, including knowledge, degree of physical and emotional wellness (as others have reported42, 48), or a fundamental belief that it simply is the professional's obligation. One can also make a general inference that there are safety elements that patients see as the sole responsibility of the health‐care professional by considering results from investigators who have examined specific clinical issues, such as patients’ [negative] attitude towards asking providers about handwashing.49 If patient engagement in safety is to be standardized, engagement limitations will need to be addressed (as possible), and a shift in thinking about the patient role will be required of some patients. Further, and as seen in other studies as well as this study, is the trustfulness and sensitivity patients have of their provider relationship, which must also be balanced.18, 50

Involving patients in research who wish to be, specifically in patient‐identified engagement safety strategies, is needed. We have not purposely designed assessment strategies to identify patient‐identified tactics or how they can be enhanced and encouraged, as feasible and appropriate. Improved information and communication about safety processes, and the rationale as to why certain actions are needed, as opposed to telling patients to do something, might engage them in a different, more effective way. In sum, and most importantly, discerning patient preferences as to how they see their engagement must be the goal of future work.

10.1. Study strengths and limitations

This study has several strengths. First, it is believed to be one of the first Canadian studies occurring in a community hospital that was designed using an interpretative approach to explore patient and family member perspectives and behaviours about their active participation in health‐care harm prevention across the spectrum of care. Other Canadian investigators have concentrated on specific processes (eg medication process51) or employed focus group methods for examining patient perceptions of safety, the influence of providers on patient involvement and strategies for improving engagement.18 Further, there was benefit in asking individuals not only what they thought or believed about participation in patient safety, but also if they would and had taken safety actions.

It is conceded that the study has limitations. One could challenge that this group of participants was not diverse, limited by the catchment area that is served by the hospital. It is offered, however, that the 5‐Facet Framework, and specifically Personal Character and Meaning of Safety themes, is aligned with these elements and are facilitative in considering and addressing where there may be differences and distinctions in this regard.

As a necessary initial step and in keeping with the study questions, the findings of this study have been presented as a 5‐Facet Framework to illuminate and describe important aspects for patient engagement in safety as expressed by patients. There was no attempt to formally characterize or delineate the specific relationships between facets, other than to generally acknowledge they were uniquely integrated for each person. While this may be a potential limitation, the utility lies in the fact that this is a building block for future work, specifically how this framework can shape the development of an assessment/evaluation tool about patient engagement in safety to be used in clinical settings.

11. CONCLUSION

While advocates have promoted that, “If the focus on patient safety doesn't begin with, and include the patient a valuable piece of the health‐care process is lost,”16 little research has been conducted to determine what patients think about having a role to ensure safety at the bedside. This study was about how patients describe their attitudes about their role at the bedside in partnering with providers to prevent harm. Based on 30 patient face‐to‐face interviews, a parsimonious 5‐Facet Framework was developed. It suggests that there are dynamic, multifaceted reasons, beliefs and circumstances why patients want and engage in safety. The future work for researchers, policymakers, providers, patients and patient advocates must be to focus on assessing what is right for each patient—some will want a more passive role; some will want active involvement. The key is talking with patients about safety throughout their care experiences, about what they see and do to promote their own safety, and to build on those approaches.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None of the authors have any conflict of interest to declare.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The support of Dr. Christina Godfrey, PhD, Associate Professor, School of Nursing, Queen's University; and Dr. Kimberley Sears, PhD, Associate Professor, School of Nursing, Queen's University, in conducting this study is acknowledged. The health‐care staff and physicians at the study site are thanked for enabling this research. The participants of this study are sincerely thanked for so willingly and honestly sharing their personal accounts.

Duhn L, Medves J. A 5‐facet framework to describe patient engagement in patient safety. Health Expect. 2018;21:1122–1133. 10.1111/hex.12815

REFERENCES

- 1. World Health Organization . Patient safety – patients for patient safety: our programme. 2018; http://www.who.int/patientsafety/patients_for_patient/programme/en/#;. Accessed July 5, 2018.

- 2. Canadian Patient Safety Institute . Tips for Patients and Families. Edmonton, AB: Canadian Patient Safety Institute; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Entwistle VA, Mello MM, Brennan TA. Advising patients about patient safety: current initiatives risk shifting responsibility. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2005;31(9):483‐494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization . Patient safety: patients for patient safety ‐ what’s new? 2018; http://www.who.int/patientsafety/patients_for_patient/en/index.html. Accessed July 5, 2018.

- 5. Consumers Advancing Patient Safety ‐ CAPS . 2018; http://www.patientsafety.org/. Accessed July 5, 2018.

- 6. p4ps® ‐ Partnership for Patient Safety ® . 2018; Partnership for patient safety. 2011; http://p4ps.net/. Accessed July 5, 2018.

- 7. Davis RE, Koutantji M, Vincent CA. How willing are patients to question healthcare staff on issues related to the quality and safety of their healthcare? An exploratory study. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17(2):90‐96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Davis RE, Sevdalis N, Vincent CA. Patient involvement in patient safety: how willing are patients to participate? BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20(1):108‐114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hibbard JH, Peters E, Slovic P, Tusler M. Can patients be part of the solution? Views on their role in preventing medical errors. Med Care Res Rev. 2005;62(5):601‐616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Marella WM, Finley E, Thomas AD, Clarke JR. Health care consumers’ inclination to engage in selected patient safety practices: a survey of adults in Pennsylvania. J Patient Saf. 2007;3(4):184‐189. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rathert C, Huddleston N, Pak Y. Acute care patients discuss the patient role in patient safety. Health Care Manage Rev. 2011;36(2):134‐144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schwappach DLB, Wernli M. Am I (un) safe here? Chemotherapy patients’ perspectives towards engaging in their safety. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19(5):e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Spath PL. Safety from the patient's point of view In: Spath PL, ed. Engaging Patients as Safety Partners: A Guide for Reducing Errors and Improving Satisfaction. Chicago, IL: Health Forum Incorporated; 2008:1‐40. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Waterman AD, Gallagher TH, Garbutt J, Waterman BM, Fraser V, Burroughs TE. Brief report: hospitalized patients’ attitudes about and participation in error prevention. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(4):367‐370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goeltz R, Hatlie MJ. Trial and error in my quest to be a partner in my health care: a patient's story. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2004;14(4):391‐399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hovey RB, Morck A, Nettleton S, et al. Partners in our care: patient safety from a patient perspective. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19(6):e59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Davis RE, Jacklin R, Sevdalis N, Vincent CA. Patient involvement in patient safety: what factors influence patient participation and engagement? Health Expect. 2007;10(3):259‐267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bishop AC, Macdonald M. Patient involvement in patient safety: a qualitative study of nursing staff and patient perceptions. J Patient Saf. 2017;13(2):82‐87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Longtin Y, Sax H, Leape LL, Sheridan SE, Donaldson L, Pittet D. Patient participation: current knowledge and applicability to patient safety. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(1):53‐62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schwappach DLB. “Against the silence”: development and first results of a patient survey to assess experiences of safety‐related events in hospital. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dowell D, Manwell LB, Maguire A, et al. Urban outpatient views on quality and safety in primary care. Healthc Q. 2005;8(2):suppl 2‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Elder NC, Jacobson CJ, Zink T, Hasse L. How experiencing preventable medical problems changed patients’ interactions with primary health care. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(6):537‐544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. The Kaiser Family Foundation . 2008 update on consumers’ views of patient safety and quality information. http://www.kff.org/kaiserpolls/posr101508pkg.cfm. Accessed July 5, 2018.

- 24. Walrath JM, Rose LE. The medication administration process: patients’ perspectives. J Nurs Care Qual. 2008;23(4):345‐352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Saxton M, Curry MA, Powers LE, Maley S, Eckels K, Gross J. “Bring my scooter so I can leave you” a study of disabled women handling abuse by personal assistance providers. Violence Against Women. 2001;7(4):393‐417. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hurst I. Vigilant watching over: mothers’ actions to safeguard their premature babies in the newborn intensive care nursery. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2001;15(3):39‐57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rathert C, Brandt J, Williams ES. Putting the ‘patient’ in patient safety: a qualitative study of consumer experiences. Health Expect. 2011;15(3):327‐336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Johnstone M‐J, Kanitsaki O. Engaging patients as safety partners: some considerations for ensuring a culturally and linguistically appropriate approach. Health Policy. 2008;90(1):1‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jeffs L, Affonso DD, Macmillan K. Near misses: paradoxical realities in everyday clinical practice. Int J Nurs Pract. 2008;14(6):486‐494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Unruh KT, Pratt W. Patients as actors: the patient's role in detecting, preventing, and recovering from medical errors. Int J Med Informatics. 2006;76(Suppl 1):S236‐S244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Weingart SN, Price J, Duncombe D, et al. Patient‐reported safety and quality of care in outpatient oncology. Joint Commission journal on quality and patient safety. 2007;33(2):83‐94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Parnes B, Fernald D, Quintela J, et al. Stopping the error cascade: a report on ameliorators from ASIPS collaborative. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16:12‐16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Herbert RD, Higgs J. Complementary research paradigms. Aust J Physiother. 2004;50(2):63‐64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Caelli K, Ray L, Mill J. ‘Clear as Mud’: toward greater clarity in generic qualitative research. Int J Qual Methods. 2003;2(2):1‐24. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ontario Hospital Association . Your Health Care: Be Involved. Toronto, ON: Ontario Hospital Association; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 36. National Literacy and Health Program , Canadian Public Health Association . Creating Plain Language Forms for Seniors: A Guide for the Public, Private and Not‐for‐Profit Sectors. Ottawa, ON: National Literacy and Health Program, Canadian Public Health Association; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldana J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook, 3rd edn Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lincoln VS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Krefting L. Rigor in qualitative research: the assessment of trustworthiness. Am J Occup Ther. 1991;45(3):214‐222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. LoBiondo‐Wood G, Haber J, Cameron C, Singh MD. Nursing Research in Canada – Methods, Critical Appraisal, and Utilization (Third Canadian Edition). Toronto, ON: Elsevier Canada; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Carman KL, Dardess P, Maurer M, et al. Patient and family engagement: a framework for understanding the elements and developing interventions and policies. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(2):223‐231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Martin HM, Navne LE, Lipczak H. Involvement of patients with cancer in patient safety: a qualitative study of current practices, potentials and barriers. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(10):836‐842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pinto A, Vincent C, Darzi A, Davis R. A qualitative exploration of patients’ attitudes towards the ‘Participate Inform Notice Know’ (PINK) patient safety video. Int J Qual Health Care. 2013;25(1):29‐34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bishop AC. Perceptions of Patient Safety: What Influences Patient and Provider Involvement?. Halifax, NS: Dalhousie University; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 45. McVeety J, Keeping‐Burke L, Harrison MB, Godfrey C, Ross‐White A. Patient and family member perspectives of encountering adverse events in health care: a systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2014;12(7):315‐373. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Clarke JN, Fletcher PC. Parents as advocates: stories of surplus suffering when a child is diagnosed and treated for cancer. Soc Work Health Care. 2004;39(1–2):107‐127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rainey H, Ehrich K, Mackintosh N, Sandall J. The role of patients and their relatives in ‘speaking up’ about their own safety – a qualitative study of acute illness. Health Expect. 2015;18(3):392‐405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Walters CB. Perceptions of hospitalized oncology patients regarding involvement in their care as a patient safety strategy across a range of health literacy levels. New York City, NY: New York University; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Pittet D, Panesar SS, Wilson K, et al. Involving the patient to ask about hospital hand hygiene: a National Patient Safety Agency feasibility study. J Hosp Infect. 2011;77(4):299‐303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rhodes P, Campbell S, Sanders C. Trust, temporality and systems: how do patients understand patient safety in primary care? A qualitative study Health Expect. 2016;19(2):253‐263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Macdonald MT, Heilemann MV, MacKinnon NJ, et al. Confirming delivery: understanding the role of the hospitalized patient in medication administration safety. Qual Health Res. 2014;24(4):536‐550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]