Abstract

AIM

To detect significant clusters of co-expressed genes associated with tumorigenesis that might help to predict stomach adenocarcinoma (SA) prognosis.

METHODS

The Cancer Genome Atlas database was used to obtain RNA sequences as well as complete clinical data of SA and adjacent normal tissues from patients. Weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) was used to investigate the meaningful module along with hub genes. Expression of hub genes was analyzed in 362 paraffin-embedded SA biopsy tissues by immunohistochemical staining. Patients were classified into two groups (according to expression of hub genes): Weak expression and over-expression groups. Correlation of biomarkers with clinicopathological factors indicated patient survival.

RESULTS

Whole genome expression level screening identified 6,231 differentially expressed genes. Twenty-four co-expressed gene modules were identified using WGCNA. Pearson’s correlation analysis showed that the tan module was the most relevant to tumor stage (r = 0.24, P = 7 × 10-6). In addition, we detected sorting nexin (SNX)10 as the hub gene of the tan module. SNX10 expression was linked to T category (P = 0.042, χ2 = 8.708), N category (P = 0.000, χ2 = 18.778), TNM stage (P = 0.001, χ2 = 16.744) as well as tumor differentiation (P = 0.000, χ2 = 251.930). Patients with high SNX10 expression tended to have longer disease-free survival (DFS; 44.97 mo vs 33.85 mo, P = 0.000) as well as overall survival (OS; 49.95 vs 40.84 mo, P = 0.000) in univariate analysis. Multivariate analysis showed that dismal prognosis could be precisely predicted clinicopathologically using SNX10 [DFS: P = 0.014, hazard ratio (HR) = 0.698, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.524-0.930, OS: P = 0.017, HR = 0.704, 95%CI: 0.528-0.940].

CONCLUSION

This study provides a new technique for screening prognostic biomarkers of SA. Weak expression of SNX10 is linked to poor prognosis, and is a suitable prognostic biomarker of SA.

Keywords: Stomach adenocarcinoma, The Cancer Genome Atlas, Weighted gene co-expression network analysis, Sorting nexin 10, Clinicopathological predictors, Disease-free survival, Overall survival

Core tip: This study used The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and clinical data to identify sorting nexin (SNX)10 as associated with poor prognosis in stomach adenocarcinoma (SA). Firstly, we downloaded the TCGA-STAD RNA-seq data through R and identified the differentially expressed genes. Weighted gene co-expression network analysis was used to clarify the connection between modules and clinical information. We then chose SNX10 as the hub-gene of the tan-module after considering module membership, genes with high gene significance, degree and Molecular Complex Detection scores. Our center’s SA data were used to evaluate our hypothesis. Our findings demonstrated that weak expression of SNX10 is linked to poor SA prognosis.

INTRODUCTION

In spite of technological progress made in diagnosis and treatment, gastric cancer continues to be the fourth most prevalent cancer type with the second highest mortality[1]. The high occurrence of cancer-related death in stomach adenocarcinoma (SA) patients may be associated with specific biological characteristics of the disease, such as challenges associated with timely diagnosis, late clinical manifestation, and high frequency of invasion and metastasis[2]. Investigation of the underlying tumorigenesis and progression of SA, the most common pathological type of gastric cancer, is a prerequisite for developing new therapeutic agents[3,4]. Although some tumorigenesis and prognostic factors, including genes[5,6] and tumor microenvironment, were evaluated[7], the precise mechanisms and signaling pathways involved are still mostly unknown. Novel molecular biomarkers that can precisely indicate the stage of disease progression and clinical results could help provide personalized treatment and a better understanding of SA pathogenesis.

Rapid technological development of biochips and next-generation sequencing has opened up new dimensions in gene expression research for medical oncology[8]. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) is a large unified compilation of multi-platform molecular profiles along with clinicopathological annotation data. TCGA offers facilities with structured analysis of potential molecular processes of various clinicopathological parameters linked to cancer[9]. Weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) was proposed for establishing co-expression modules or networks of genes to explore the correlation among different groups of genes, or within groups of genes, and clinical features[10]. These modules are built upon large gene expression profiles and the differences between the centrally located genes (hub genes) that drive the crucial cellular signaling pathways within important cell types[11,12]. The WGCNA method provides a functional interpretation tool for systems biology and has led to new insights into the pathophysiology of SA.

In the present study, we used gene expression data from TCGA to create a co-expression network using differentially expressed genes (DEGs) related to SA progression, and defined the gene clusters closely related to SA through WGCNA. Transcriptomics analysis enabled us to identify sorting nexin (SNX)10, a tumor suppressor, which showed over-expression in para-carcinoma tissues and gastric epithelial cells (GSE-1) compared to that in SA tissue and cells. We investigated the correlation between SNX10 expression and the related clinicopathological parameters in SA patients. The prognostic value of SNX10 in SA was also evaluated.

Our research provides a novel and extensive application platform for the identification of SA-related genes, which may be useful to identify novel molecular targets and develop competent therapeutic strategies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

TCGA gene expression profiles

The RNA sequencing dataset and corresponding clinical records of SA patients were obtained from TCGA (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/, Project ID: TCGA-STAD). The RTCGA Toolbox package in the R platform was used to download the raw dataset of RNA sequences[13]. A total of 406 samples were available in TCGA, which included 375 tumor and 31 normal tissue samples. Hub genes were identified from 375 tumor tissue samples (with complete clinical data) using WGCNA.

Screening for DEGs

Differentially expressed RNAs were identified by the package R[14]. The trimmed mean of M values was used to obtain gene read counts with one scaling normalized factor[15]. We calculated the significance of RNAs using the negative binomial model followed by correction of P values by the Benjamini-Hochberg method[16]. Significantly expressed RNAs were identified using adjusted P values of 0.05 and fold changes of 1.

Construction of WGCN

The WGCNA R package was used to establish co-expression networks of genes[10]. Towards this end, 375 tumor samples with expression of 6,232 DEGs and related clinical data were used. The weighted adjacency matrix was created from a power function that was dependent on a soft-thresholding parameter gram, deep split was taken as 4, and we considered the cutoff line as 0.15 for the module dendrogram and merged modules. The network was visualized by Cytoscape 3.5.1[17]. The network module was filtered and studied in Cytoscape using Molecular Compgram, deep split was taken as 4, and we considered the cutoff line as 0.15 for the module dendrogram and merged modules. The network was visualized by Cytoscape 3.5.1[17]. The network module was filtered and studied in Cytoscape using Molecular Complex Detection (MCODE).

Clinically significant module identification and module functional annotation

We identified biologically significant modules using Pearson’s correlation test to evaluate the association between modules and clinical features. Age, tumor stage and tumor grade were chosen as clinical traits. The modules showing the highest correlation with clinical features were chosen. The Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) version 6.8 (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/)[18] was used to categorize the gene data of the target module as follows: biological process FAT, cell component FAT, and molecular function FAT datasets of Gene Ontology (GO) functional[19,20] and pathway enrichment analysis using Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)[21]. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Identification of hub genes

We calculated the gene significance (GS), high module membership (MM) and MCODE score for different genes in the modules of interest. Based on GS, MM and MCODE score, hub genes were identified.

Ethics statement

The study was sanctioned by the Ethics Committee, Liaoning Cancer Hospital and Institute. Informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to surgery.

Patients and tissue samples

The study cohort comprised 362 patients with SA who underwent gastrectomy at the Liaoning Cancer Hospital and Institute (Shenyang, China) from January 2010 to December 2012. All patients underwent D2 lymph node dissection and gastrectomy at the first consultation. None of the enrolled patients were treated with preoperative chemotherapy or radiotherapy. All patients yielded sufficient paraffin-embedded tumor specimens. Patients with absolute adenocarcinoma, mixed carcinoma or signet ring cell carcinoma were excluded. Tumor staging was done as per the criteria detailed in the 8th edition of the TNM Staging Manual of American Joint Committee on Cancer/Union International Control Center (2017). The average age of patients was 59 years (range 33-80 years), and there were 248 men (68.5%) and 114 women (31.5%). Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy was administered to patients with staging worse than IIA. The clinicopathological parameters analyzed included: age, gender, Bormann type, age, tumor size, tumor location, Lauren type, perineural invasion, tumor differentiation, T category, invasion of blood vessel, N category, and TNM stage (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and univariate analysis, n = 362

| Characteristic | n (%) |

DFS |

OS |

||||

| Time (mo) | P value | F value | Time (mo) | P value | F value | ||

| Age (median, yr) | 0.138 | 2.209 | 0.373 | 0.795 | |||

| ≥ 60 | 192 (53.0) | 37.25 | 44.18 | ||||

| < 60 | 170 (47.0) | 41.26 | 46.29 | ||||

| Gender | 0.194 | 1.695 | 0.463 | 0.540 | |||

| Male | 248 (68.5) | 37.94 | 44.58 | ||||

| Female | 114 (31.5) | 41.72 | 46.46 | ||||

| Bormann type | 0.000 | 27.349 | 0.000 | 23.230 | |||

| I | 28 (7.7) | 64.04 | 64.04 | ||||

| II | 161 (44.5) | 45.96 | 51.32 | ||||

| III | 167 (46.1) | 22.80 | 36.72 | ||||

| IV | 6 (1.7) | 16.03 | 27.33 | ||||

| Tumor size | 0.000 | 31.865 | 0.000 | 25.094 | |||

| ≥ 5 cm | 153 (42.3) | 30.59 | 38.46 | ||||

| < 5 cm | 209 (57.7) | 45.38 | 50.09 | ||||

| Location | 0.212 | 1.558 | 0.403 | 0.912 | |||

| Up | 76 (21.0) | 34.55 | 42.11 | ||||

| Middle | 102 (28.2) | 40.75 | 46.36 | ||||

| Low | 184 (50.8) | 40.13 | 45.78 | ||||

| Lauren type | 0.241 | 1.428 | 0.214 | 1.549 | |||

| Intestinal | 166 (45.9) | 41.87 | 47.77 | ||||

| Mixed carcinoma | 84 (23.2) | 39.07 | 44.99 | ||||

| Diffuse | 112 (30.9) | 35.62 | 42.07 | ||||

| Tumor differentiation | 0.000 | 17.711 | 0.000 | 15.214 | |||

| Moderate and high | 176 (48.6) | 44.84 | 49.83 | ||||

| Poor | 186 (51.4) | 33.74 | 40.76 | ||||

| Vessel invasion | 0.000 | 21.849 | 0.000 | 20.983 | |||

| Yes | 107 (29.6) | 29.67 | 37.02 | ||||

| No | 255 (70.4) | 43.10 | 48.59 | ||||

| Perineural invasion | 0.000 | 17.726 | 0.000 | 15.346 | |||

| Yes | 88 (24.3) | 28.14 | 36.38 | ||||

| No | 274 (75.7) | 42.66 | 48.00 | ||||

| T category | 0.000 | 70.121 | 0.000 | 49.574 | |||

| T1 | 68 (18.8) | 65.72 | 65.75 | ||||

| T2 | 24 (6.6) | 60.25 | 62.00 | ||||

| T3 | 12 (3.3) | 59.04 | 61.33 | ||||

| T4 | 258 (71.3) | 29.29 | 37.46 | ||||

| N category | 0.000 | 248.092 | 0.000 | 223.946 | |||

| N0 | 152 (42.0) | 61.93 | 63.47 | ||||

| N1 | 62 (17.1) | 36.73 | 48.52 | ||||

| N2 | 68 (18.8) | 24.07 | 33.05 | ||||

| N3 | 80 (22.1) | 10.49 | 17.52 | ||||

| TNM stage | 0.000 | 386.623 | 0.000 | 231.577 | |||

| I | 77 (21.3) | 64.47 | 65.69 | ||||

| II | 87 (24.0) | 62.99 | 64.49 | ||||

| III | 194 (53.6) | 19.07 | 29.04 | ||||

| IV | 4 (1.1) | 5.50 | 9.50 | ||||

| SNX10 | 0.000 | 21.849 | 0.000 | 18.278 | |||

| Over- expression | 172 (47.5) | 44.97 | 49.95 | ||||

| Weak-expression | 190 (52.5) | 33.85 | 40.84 | ||||

DFS: Disease-free survival; OS: Overall survival; SNX10: Sorting nexin 10.

Follow-up evaluation was conducted every 3-6 mo after surgery for 5 years, which included physical examination, pulmonary, abdominal, and pelvic computed tomography scan, blood count, endoscopy, and liver function tests. The dates of first evidence of recurrence and death were recorded for each case. Survival was estimated as the duration between operation and final follow-up or demise. The final date of investigation was May 1, 2018. The tenure between the resection date and diagnosis of first relapse was considered to be disease-free survival (DFS). Overall survival (OS) was calculated as the time between surgery and death.

Immunohistochemistry

Tissue sections (5 μm thick) were fixed on slides coated with poly-L-lysine. SNX10 antibody (Abcam, 1:150, Cambridge, United Kingdom) was used for immunostaining of sections, and visualized by treatment with suitable biotin-conjugated secondary antibodies. Immmunoperoxidase was used for immunostaining of sections, and treatment with suitable biotin-conjugated secondary antibodies as well as immmunoperoxidase detection involving diaminobenzidine (DAB) substrate (Boster, China) and the Vectastain ABC Elite kit (Linaris, Wertheim, Germany) were used for visualization.

Evaluation of immunohistochemical staining

Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining of SNX10 was independently scored by two pathologists. Staining intensity and the ratio of SNX10-positive cells were measured to obtain the final score. This ratio was enumerated as average percentage of SNX10-positive cells in five different fields of 200× magnification. The positive cells were scored as follows: 0, negative; 1, ≤ 10% positive cells; 2, 10%-50% positive cells; 3, > 50% and ≤ 75% positive cells; and 4, > 75% positive cells. Staining intensity was scored between 0 and 3 (negative, weak, moderate, and strong, respectively). The final score was the product of the two individual scores. Median score of SNX10 = 4 served as the cut-off point. Patients were classified into either the over-expression or weak expression group.

Cell culture

GSE-1 is a human gastric epithelial cell line, and SGC-7901 and BGC-823 are human gastric cancer cell lines. Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium enriched with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, United States), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Invitrogen) at a temperature of 37 °C humidified with < 5% CO2. Cells were obtained from China Medical University (Shenyang, China). All experiments were performed in triplicate with independent cell cultures.

Real-time polymerase chain reaction

Total cellular RNA was extracted by TRIzol (Invitrogen) cell separation reagent and the PURELINK miRNA Isolation Kit (Invitrogen). The Promega miRNA First-Strand cDNA Core Kit (Promega, Madison, WI, United States) was used for reverse transcription of 500 ng RNA. Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (LightCycler 480; Roche AG, Basel, Switzerland) was performed using SYBR Master Mixture (Takara Bio, Kusatsu, Japan). Samples were run in triplicate. U6 DNA served as a loading control. Fold changes in mRNA expression between different cells were determined by 2−ΔΔCT normalization. The following forward and reverse expression primers were used for SNX10: 5’-GAAGGTCACTGTCTGGATTA-3’ and 5’-GTCTGCGTCTGGTTGTAA-3’, respectively.

Western blotting

Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (10%-15%) was used to resolve 20 μg cellular proteins and blotted onto polyvinylidende difluoride membranes. After transfer, the membranes were incubated in TBS-Tween buffer supplemented with 20 mmol/L Tris-HCl, 5% nonfat milk, 150 mmol/L NaCl, and 0.05% Tween-20 (pH 7.5) for 1 h at 21 °C, followed by treatment with primary antibodies against SNX10 (1:200; Abcam), and β-actin (1:4000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, United States) overnight at 4 °C, and finally incubated with secondary antibody (1:5000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). β-Actin served as the endogenous loading control for protein quantity. The gray value of the expression of all proteins was measured using ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD, United States). Data are presented as the mean of three independent observations.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 22.0. One-way analysis of variance was used to compare the mean values between groups. Data from the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test reflected the correlation between clinicopathological variables and biomarkers (SNX10). Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated from the data and univariate survival analysis was performed by log-rank test. We tested the effect of prognostic biomarkers on survival rate through the Cox proportional hazards model.

RESULTS

Differentially expressed mRNAs in SA

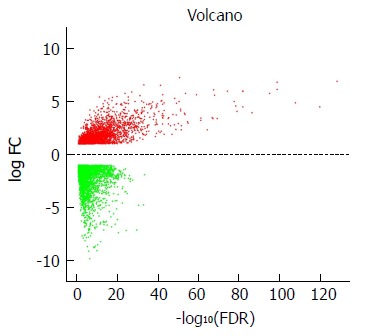

DEG screening was carried out using the TCGA-STAD dataset including 124375 SA samples and 31 para-carcinoma tissues. R language (Edge R) was used to estimate 6231 expression data sets. From the expression data of 24991 mRNAs, 6231 differentially expressed mRNAs were identified (Figure 1), which were further investigated by WGCNA.

Figure 1.

Volcano plot of the differentially expressed mRNAs between stomach adenocarcinoma and para-carcinoma tissues. Red indicates high expression and green indicates low expression (|log2FC| > 1 and adjusted P value < 0.05). The X axis represents a false discovery rate (FDR) value and the Y axis represents a log2FC. Differential mRNAs were calculated by edgeR. There were 2456 highly expressed and 3775 lowly expressed mRNAs. This volcano plot was conducted by the ggplot2 package of R language. FDR: False discovery rate.

WGCN construction

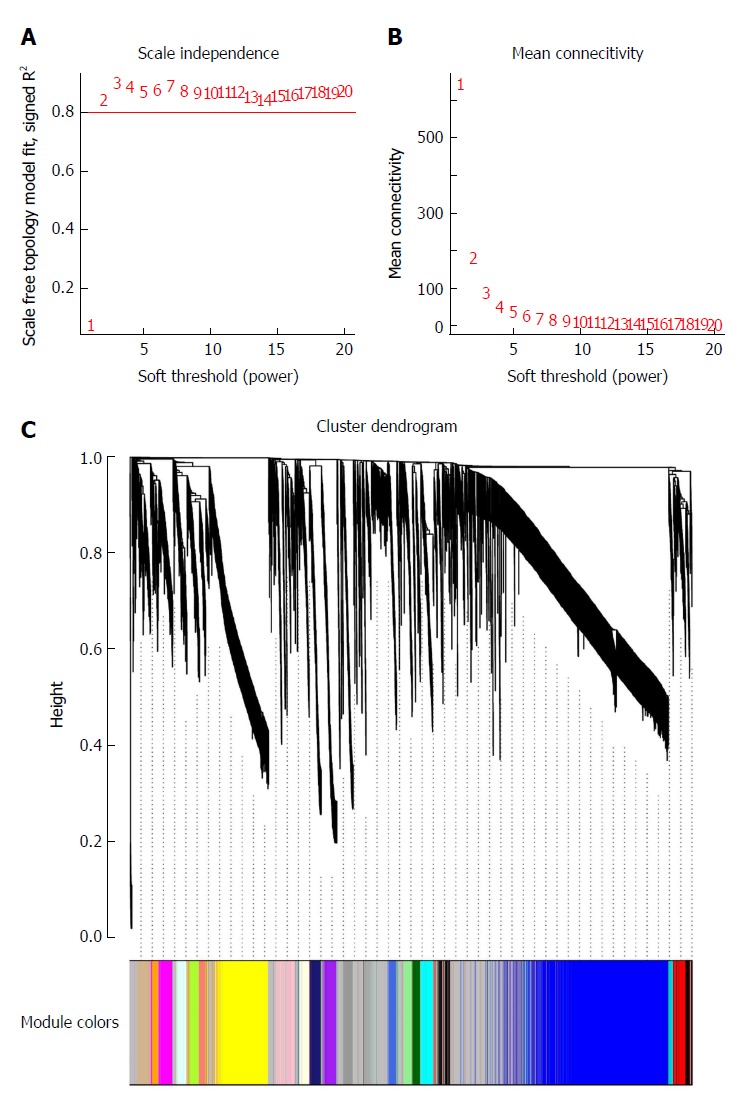

To clarify the functional modules in SA patients, the expression values of 6231 DEGs were included for constructing a co-expression network with the WGCNA package. We selected β = 2 as the soft-thresholding power to construct a scale-free network (Figure 2A and B). Twenty-four distinct co-expression modules were identified that contained 41-1038 genes per module (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Determination of soft-thresholding power in weighted gene co-expression network analysis and gene clustering dendrograms. A: Analysis of the scale-free fit index for various soft-thresholding powers (β); B: Analysis of the mean connectivity for various soft-thresholding powers; C: Gene clustering tree (dendrogram) obtained by hierarchical clustering of adjacency-based dissimilarity.

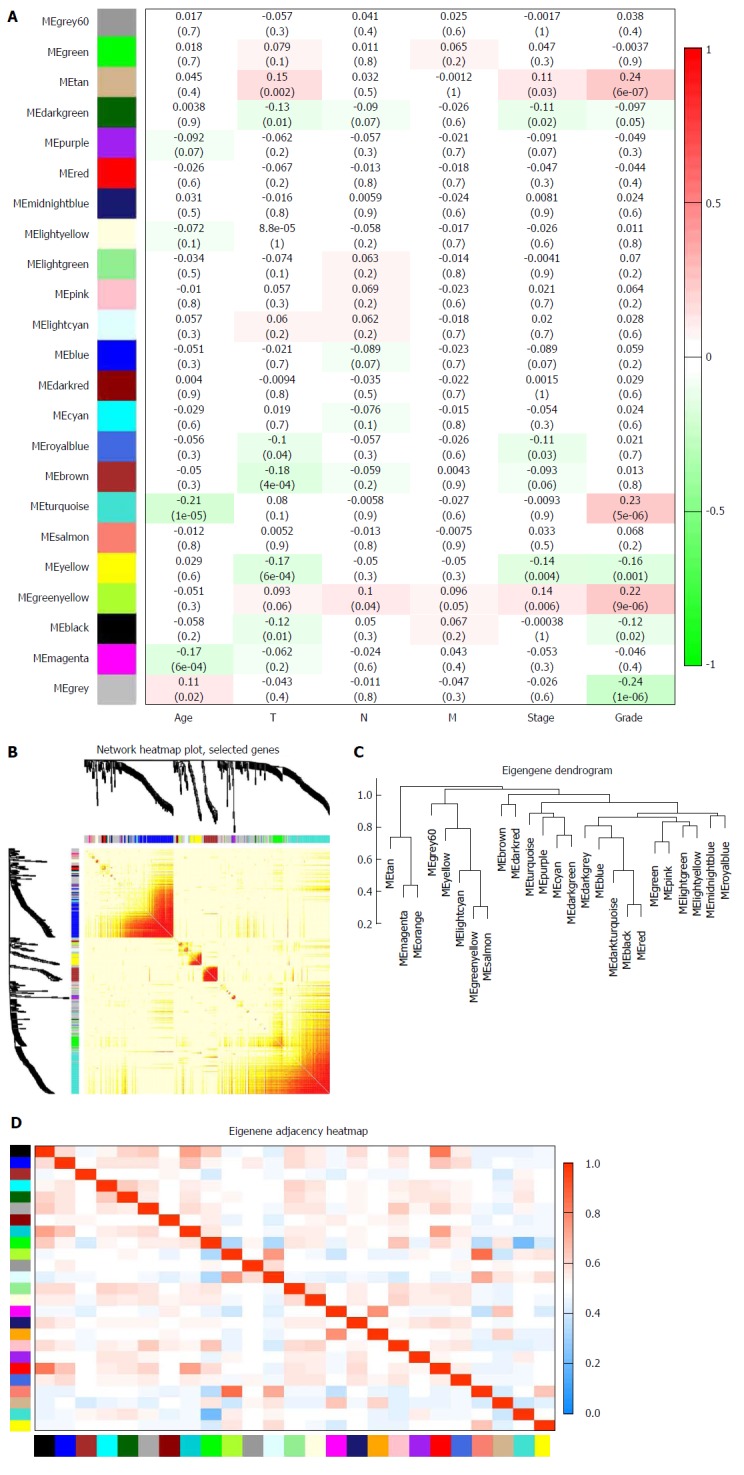

Identifying key clinically significant modules

Biologically, the most relevant module has the highest association with clinical features of SA patients. The tan module had the highest association with tumor grade (r = 0.24, P = 7 × 10-6; Figure 3A) and was selected for subsequent analyses. The tan module also had the second-highest association with tumor stage (r = 0.11, P = 0.03; Figure 3A). TOM plot function from the WGCNA package was used to generate a TOM plot (Figure 3B). Eigengene was treated as a representative profile to quantify module similarity. The dendrogram showed the correlation between modules (Figure 3C). The heat map revealed eigengene adjacency of modules (Figure 3D). MM and GS data (Supplementary Table 1) were exported for hub gene identification. Network analysis revealed that expression and regulation of tumor-related genes were altered in SA as opposed to non-tumor stomach tissues.

Figure 3.

Identification of modules associated with clinical traits of stomach adenocarcinoma. A: Heat map of the correlation between module eigengenes and clinical traits of stomach adenocarcinoma (SA); B: Topological overlap matrix (TOM) plot; C: Visualization of hierarchical clustering dendrogram of the eigengenes. The eigen gene network represents the relationships among modules; D: Heat map of the eigengene adjacency. The color bars on the left and below indicate the module for each row or column.

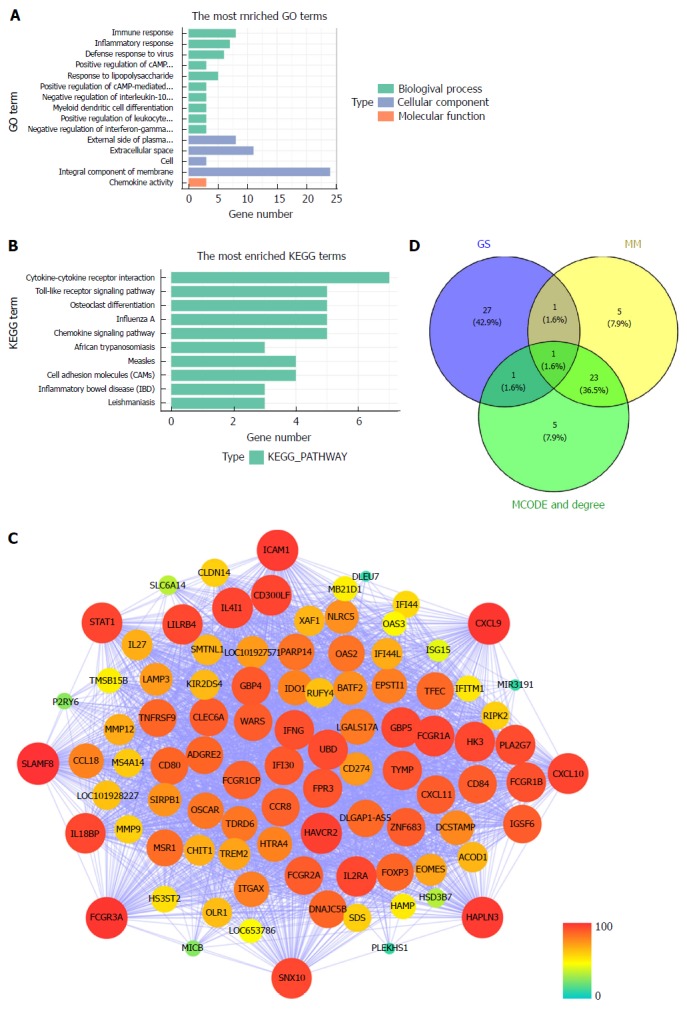

Module functional annotation and hub gene identification

All 93 DEGs in the tan module were submitted to the online database DAVID to identify representative GO terms and KEGG pathways[22] for further elucidation of the functional properties of the DEGs. GO analysis showed that the tan module contained biological processes focused on immune response, inflammatory response and defense response to virus infection. These cellular components were focused on the external side of the plasma membrane, extracellular space and cells. Molecular function mainly focused on chemokine activity (Figure 4A, Supplementary Table 2). Figure 4B and Supplementary Table 3 show the most significantly enriched pathways of the tan module following KEGG pathway analysis. The DEGs were enhanced in the cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction, osteoclast differentiation, and Toll-like receptor signaling pathway. GS in the tan module of weighted co-expression was exported to Cytoscape software for WGCN construction (Figure 4C). We sorted the tan module DEGs according to MM, GS and MCODE. We selected the top 30 members of each group and took the intersection (Figure 4D, Supplementary Table 1). SNX10 was identified as the hub gene.

Figure 4.

Module functional annotation and hub gene identification. A and B: Gene Ontology (GO) functional and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis for genes in the tan-module. The X-axis shows the number of genes and the Y-axis shows the GO and KEGG terms; C: Weighted co-expression network for tan-module genes. (nodes are colored according to the degree, and sized according to the Molecular Complex Detection (MCODE) score); D: Hub genes were screened with module membership (MM), gene significance (GS) and MCODE. GO: Gene Ontology; KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; GS: Gene significance; MM: Module membership; MCODE: Molecular Complex Detection.

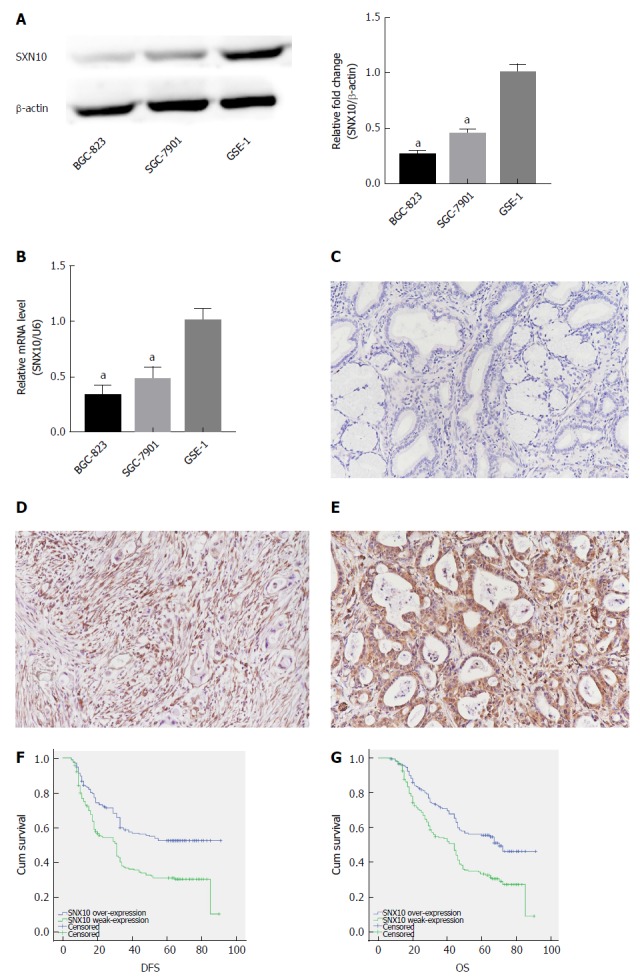

Expression of SNX10 in SA cells and specimens

Western blotting and real-time PCR showed that SNX10 was weakly expressed in BGC-823 and SGC-7901 cells relative to control GES-1 cells (Figure 5A and B, P < 0.05). We examined levels of SNX10 by immunohistochemistry in 362 SA tissue samples to investigate the role of SNX10 in SA tissue. We found that 195 (53.9%) tissues showed weak SNX10 expression (Figure 5D), and 167 (46.1%) showed high expression (Figure 5E). The corresponding negative results are shown in Figure 5C.

Figure 5.

Expression of sorting nexin 10 in stomach adenocarcinoma cells and tissue and its effect on survival. A: Sorting nexin 10 (SNX10) protein expression in stomach adenocarcinoma (SA) cell lines (SGC-7901 and BGC-823) and the human normal gastric epithelial cell line (GSE-1) by western blot. β-actin was used as a loading control; n = 3, aP < 0.05; B: SNX10 mRNA expression in SGC-7901, BGC-823 and GSE-1 by real time-PCR; n = 3, aP < 0.05; C: The representative negative result in SA tissue; magnifications are 200 ×; D: SNX10 was weakly expressed in SA tissue; magnifications are 200 ×; E: SNX10 had strong expression in SA tissue; magnifications are 200 ×; F: Disease free survival curves stratified by SNX10 expression (P = 0.00); G: Overall survival curves stratified by SNX10 expression (P = 0.00). DFS: Disease-free survival; OS: Overall survival; SNX10: Sorting nexin 10.

Correlations between clinicopathological factors and expression of SNX10

Table 2 summarizes the relationship between clinicopathological features and SNX10 expression. According to χ2 or Fisher’s exact test, expression of SNX10 was associated with T category (P = 0.042, χ2 = 8.708), N category (P = 0.000, χ2 = 18.778), TNM stage (P = 0.001, χ2 = 16.744) and tumor differentiation (P = 0.0000, χ2 = 251.930), which was consistent with our WGCNA forecast. The Pearson correlation between SNX10 and tumor differentiation was 0.834 (P = 0.000).

Table 2.

Sorting nexin 10 expression and clinicopathologic characteristics, n (%)

| Characteristic |

SNX10 |

|||

| High | Low | P value | χ2 value | |

| 172 (47.5) | 190 (52.5) | |||

| Age (median, yr) | 0.599 | 0.342 | ||

| ≥ 60 | 94 (49.0) | 98 (51.0) | ||

| < 60 | 78 (45.9) | 92 (54.1) | ||

| Gender | 0.385 | 0.755 | ||

| Male | 114 (46.0) | 134 (54.0) | ||

| Female | 58 (50.9) | 56 (49.1) | ||

| Tumor size | 0.566 | 0.330 | ||

| ≥ 5 cm | 70 (45.8) | 83 (54.2) | ||

| < 5 cm | 102 (48.8) | 107 (51.2) | ||

| Location | 0.490 | 1.426 | ||

| Up | 33 (43.4) | 43 (56.6) | ||

| Middle | 46 (45.1) | 56 (54.9) | ||

| Low | 93 (50.5) | 91 (49.5) | ||

| Bormann type | 0.167 | 5.071 | ||

| I | 13 (46.4) | 15 (53.6) | ||

| II | 85 (52.8) | 76 (47.2) | ||

| III | 73 (43.7) | 94 (56.3) | ||

| IV | 1 (16.7) | 5 (83.3) | ||

| Lauren type | 0.172 | 3.521 | ||

| Intestinal | 76 (45.8) | 90 (54.2) | ||

| Mixed carcinoma | 35 (41.7) | 49 (58.3) | ||

| Diffuse | 61 (54.5) | 51 (45.5) | ||

| Tumor differentiation | 0.000 | 251.93 | ||

| Moderate and high | 159 (90.3) | 17 (9.7) | ||

| Poor | 13 (7.0) | 173 (93.0) | ||

| Vessel invasion | 0.264 | 1.246 | ||

| Yes | 46 (43.0) | 61 (57.0) | ||

| No | 126 (49.4) | 129 (50.6) | ||

| Perineural invasion | 0.657 | 0.198 | ||

| Yes | 40 (45.5) | 48 (54.5) | ||

| No | 132 (48.2) | 142 (51.8) | ||

| T category | 0.042 | 8.708 | ||

| T1 | 40 (58.8) | 28 (41.2) | ||

| T2 | 11 (45.8) | 13 (54.2) | ||

| T3 | 8 (66.7) | 4 (33.3) | ||

| T4 | 113 (43.8) | 145 (56.2) | ||

| N category | 0.000 | 18.778 | ||

| N0 | 92 (60.5) | 60 (39.5) | ||

| N1 | 25 (40.3) | 37 (59.7) | ||

| N2 | 28 (41.2) | 40 (58.8) | ||

| N3 | 27 (33.8) | 53 (66.3) | ||

| TNM stage | 0.001 | 16.744 | ||

| I | 44 (57.1) | 33 (42.9) | ||

| II | 53 (60.9) | 34 (39.1) | ||

| III | 73 (37.6) | 121 (62.4) | ||

| IV | 2 (50.0) | 2 (50.0) | ||

SNX10: Sorting nexin 10.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of SA patients

Of the 362 patients, 345 had clinical follow-up data but 209 (57.7%) patients died before the end of follow-up. The median DFS was 33.0 mo (range 5-91 mo), and median OS was 45.50 mo (range 7-91 mo). The Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test were used to study the clinical outcomes and the clinicopathological factors. Patients with weak expression of SNX10 had longer DFS (44.97 vs 33.85 mo, P < 0.05) and OS (49.95 mo vs 40.84 mo, P < 0.05) (Table 1, Figure 5F and G). Clinicopathological parameters with P < 0.05 in univariate analysis were used for multivariate analysis. Cox proportional hazards model was applied using a backward stepwise method. Higher TNM stage predicted shorter DFS and OS after adjusting for Bormann type, tumor size and other factors (DFS: P = 0.000, HR = 78.873, 95%CI: 36.367-171.057; OS: P = 0.000, HR = 76.703, 95%CI: 35.60-165.262; Table 3). Weak expression of SNX10 also served as an independent prognostic factor for prediction of DFS and OS (DFS: P = 0.014, HR = 0.698, 95%CI: 0.524-0.930; OS: P = 0.017, HR = 0.704, 95%CI: 0.528-0.940; Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis of significant prognostic factors for survival in stomach adenocarcinoma patients

| Variable |

DFS |

OS |

||||

| P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | |

| Bormann | 0.418 | 1.109 | 0.864-1.424 | 0.531 | 1.083 | 0.844-1.388 |

| Tumor size | 0.395 | 0.884 | 0.665-1.175 | 0.625 | 0.931 | 0.701-1.238 |

| Tumor differentiation | 0.686 | 0.874 | 0.455-1.678 | 0.658 | 0.859 | 0.440-1.679 |

| Vessel invasion | 0.292 | 1.424 | 0.738-2.746 | 0.419 | 1.320 | 0.674-2.586 |

| Perineural invasion | 0.171 | 0.815 | 0.607-1.093 | 0.269 | 0.864 | 0.628-1.139 |

| TNM stage | 0.000 | 78.873 | 36.367-171.057 | 0.000 | 76.703 | 35.600-165.262 |

| SNX10 expression | 0.014 | 0.698 | 0.524-0.930 | 0.017 | 0.704 | 0.528-0.940 |

DFS: Disease-free survival; OS: Overall survival; SNX10: Sorting nexin 10; HR: Hazard ratio; CI: Confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

The tumorigenesis and prognosis of SA are dependent on the interaction of several factors, such as overexpression of oncogenes, silencing of tumor suppressor genes, tumor biological characteristics and clinical factors. According to the genetic factors in SA occurrence, development and prognosis, RNA sequencing could further help to study the function of genes at the whole genome level. As a systematic biology method to describe how clinical features associate with genes, WGCNA was applied to investigate co-expression between SA tissue and normal samples. WGCNA, an algorithm for a scale-free network, is widely used in RNA sequencing and profiling microarray analysis[10]. The clustering criteria of WGCNA are focused on biological significance, in contrast to the other clustering algorithms that use geometric distance between data for clustering. A module in WGCNA depicted a group of genes in different tissue samples with similar trends in physiological processes or expression. After module identification, WGCNA calculates the stability of the module and indicates how that correlates with clinical features. The characteristic of a scale-free network is that it highlights several special nodes whose connectivity is significantly greater than that of other general nodes. The special nodes are called hub genes. Thus, it is the correlation between the hub genes of interest and clinical features that can be used to reveal the main causes of disease progression.

In the present study, DEGs were obtained by comparing SA and normal gastric epithelial tissue samples. WGCNA identified 24 distinct co-expression modules from DEGs. The highest positive correlation between the tan module and tumor grade was found through the gene module related to clinical features. Using comprehensive analyses of GS, MM, degree, and MCODE score, we inferred that SNX10 was the hub gene of the tan module. SNX10 is a member of the SNX family, which possesses an evolutionarily conserved PX or phosphoinositide-binding protein with a Phox homology domain. SNX10 is involved in different endosomal transport pathways by targeting endosomal membranes through the PX domain[23,24].

SNX10 only has one PX domain, and is the most basic structured member of the SNX family. Even so, its biological function is still largely unknown. Loss of SNX10 function may be an important therapeutic strategy for inflammatory bowel disease[25]. Chen et al[26] have suggested that SNX10 has interactions with V-ATPase. SNX10 has regulatory functions in membrane trafficking and endosomal stabilization, and SNX10 overdrive can lead to formation and accumulation of giant vacuoles that can be inhibited by brefeldin A[27]. Shen et al[28] have reported that SNX10 is significantly downregulated and acts as a suppressor in human colorectal cancer (CRC). It can increase activity of chaperone-mediated autophagy and decrease expression of p21Cip1/WAF1, thus regulating tumorigenesis and progression. Downregulation of SNX10 leads to loss of control of amino acid metabolism, which activates the mTOR signaling pathway and promotes tumorigenesis of CRC[29].

Gerber et al[30] have described two variants of SNX10 gene as candidates for CRC susceptibility. In addition, SNX10 exhibits the characteristics of a suppressor gene and acts as a potential marker of hepatic carcinoma, which may be regulated by miRNA-30d[31]. These findings show that inhibition of SNX10 expression may be closely related to tumorigenesis and tumor progression, but its clinical significance in SA remains unclear. Using western blotting and real-time PCR, we have revealed differential expression between SNX10 in SA cells and normal gastric epithelial cells shown through bioinformatics analysis. We also confirmed the correlation between SNX10 and tumor grade based on the biopsy database in our center. Hence, this study is believed to be the first to confirm SNX10 as a prognostic factor for DFS and OS in SA patients.

This study had some limitations. First, we did not analyze the effect of SNX10 on the phenotype of SA. The molecular regulatory mechanism of SNX10 also needs to be further explored in future studies. Second, this was a single-center retrospective study. Further studies should be conducted to validate our findings and highlight the mechanistic impact of SX10 on SA tumorigenesis and progression. In addition, sample size needs to be increased for further statistical analysis.

In summary, WGCNA as well as other methods were used to study RNA sequences and clinical data of SA patients from the TCGA database. We conclude that SNX10 is a hub gene associated with tumor grade and acts as an independent prognostic factor for DFS and OS in SA patients. SNX10 has the potential to become a novel prognostic indicator contributing to personalized therapy. However, more experiments are needed to validate the clinical and biological functions of SNX10.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Stomach adenocarcinoma (SA) is by far the most prevalent pathologic version of gastric cancer, whose prognosis is influenced by the complex gene interactions involved in tumor progression. Guidelines have identified the correlation between clinical prognosis and tumor stage and grade. Detection of significant clusters of co-expressed genes or representative biomarkers associated with tumor stage or grade may prompt to highlight the mechanisms of tumorigenesis and tumor progression, and might be helpful to predict SA patient prognosis.

Research motivation

To detect significant clusters of co-expressed genes associated with tumorigenesis, which may help predict SA patient prognosis. The weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) method provided a functional interpretation tool for systems biology and led to new insights into the pathophysiology of SA.

Research objectives

The aim of the present study is to reveal a novel biomarker of SA and evaluate the prognostic value of it in SA.

Research methods

The RNA-seq dataset and clinical dataset of SA in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) were used in this study. The WGCNA was used to identify meaningful modules and hub genes. A 326 patients database was used to evaluate the clinical significance of hub genes via survival analysis.

Research results

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (6231) were obtained through whole genome expression level screening. Gene modules (24) were identified using WGCNA, which were observed to be co-expressed. Pearson’s correlation analysis showed the tan-module to be the most relevant to tumor stages. In addition, we detected SNX10 as the hub gene of the tan-module. SNX10 expression was linked to TNM stage and tumor differentiation. Patients with high SNX10 expression trended to have longer disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival in univariate analysis. Multivariate analysis also showed that dismal prognosis could be precisely predicted clinicopathologically using SNX10. However, more experiments are needed to validate the clinical and biological functions of SNX10.

Research conclusions

WGCNA as well as other methods were employed to study RNA-seq and the clinical data of SA patients from TCGA. SNX10 was considered as a hub gene associated with tumor grade and acted as an independent prognostic factor in SA patient DFS as well as overall survival. It has the potential to become a novel prognostic indicator, thus contributing to personalized therapy.

Research perspectives

Our research team will explore the molecule function of SNX10 by establishing animal models. We will also explore the mutual regulatory mechanism of SNX10 through mass spectrometry analysis and co-immunoprecipitation.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Institutional review board statement: The study was reviewed and approved by the Faculty of Science Ethics Committee at Liaoning Cancer Hospital and Institute (Cancer Hospital of China Medical University) (20150308-2).

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest related to this study.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

ARRIVE guidelines statement: The authors have read the ARRIVE guidelines, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the ARRIVE guidelines.

Peer-review started: August 2, 2018

First decision: October 5, 2018

Article in press: October 21, 2018

P- Reviewer: D’Ugo DM, Lim SJ S- Editor: Ma RY L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Bian YN

Contributor Information

Jun Zhang, Department of Gastric Cancer, Liaoning Cancer Hospital and Institute (Cancer Hospital of China Medical University), Shenyang 110042, Liaoning Province, China.

Yue Wu, Department of Emergency, Sheng Jing Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang 110042, Liaoning Province, China.

Hao-Yi Jin, Pancreatic and Thyroid Surgery Department, Sheng Jing Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang 110042, Liaoning Province, China.

Shuai Guo, Department of Gastric Cancer, Liaoning Cancer Hospital and Institute (Cancer Hospital of China Medical University), Shenyang 110042, Liaoning Province, China.

Zhe Dong, Department of Gastric Cancer, Liaoning Cancer Hospital and Institute (Cancer Hospital of China Medical University), Shenyang 110042, Liaoning Province, China.

Zhi-Chao Zheng, Department of Gastric Cancer, Liaoning Cancer Hospital and Institute (Cancer Hospital of China Medical University), Shenyang 110042, Liaoning Province, China.

Yue Wang, Department of Gastric Cancer, Liaoning Cancer Hospital and Institute (Cancer Hospital of China Medical University), Shenyang 110042, Liaoning Province, China.

Yan Zhao, Department of Gastric Cancer, Liaoning Cancer Hospital and Institute (Cancer Hospital of China Medical University), Shenyang 110042, Liaoning Province, China. zhaoyan@cancerhosp-ln-cmu.com.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang SM, Tie J, Wang WL, Hu SJ, Yin JP, Yi XF, Tian ZH, Zhang XY, Li MB, Li ZS, et al. POU2F2-oriented network promotes human gastric cancer metastasis. Gut. 2016;65:1427–1438. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lordick F, Shitara K, Janjigian YY. New agents on the horizon in gastric cancer. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:1767–1775. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corso S, Giordano S. How Can Gastric Cancer Molecular Profiling Guide Future Therapies? Trends Mol Med. 2016;22:534–544. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang J, Wu Y, Lin YH, Guo S, Ning PF, Zheng ZC, Wang Y, Zhao Y. Prognostic value of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha and prolyl 4-hydroxylase beta polypeptide overexpression in gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:2381–2391. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i22.2381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuse N, Kuboki Y, Kuwata T, Nishina T, Kadowaki S, Shinozaki E, Machida N, Yuki S, Ooki A, Kajiura S, et al. Prognostic impact of HER2, EGFR, and c-MET status on overall survival of advanced gastric cancer patients. Gastric Cancer. 2016;19:183–191. doi: 10.1007/s10120-015-0471-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thompson ED, Zahurak M, Murphy A, Cornish T, Cuka N, Abdelfatah E, Yang S, Duncan M, Ahuja N, Taube JM, et al. Patterns of PD-L1 expression and CD8 T cell infiltration in gastric adenocarcinomas and associated immune stroma. Gut. 2017;66:794–801. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vincent AT, Derome N, Boyle B, Culley AI, Charette SJ. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) in the microbiological world: How to make the most of your money. J Microbiol Methods. 2017;138:60–71. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2016.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu J, Lichtenberg T, Hoadley KA, Poisson LM, Lazar AJ, Cherniack AD, Kovatich AJ, Benz CC, Levine DA, Lee AV, et al. An Integrated TCGA Pan-Cancer Clinical Data Resource to Drive High-Quality Survival Outcome Analytics. Cell. 2018;173:400–416.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Langfelder P, Horvath S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:559. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Botía JA, Vandrovcova J, Forabosco P, Guelfi S, D’Sa K; United Kingdom Brain Expression Consortium, Hardy J, Lewis CM, Ryten M, Weale ME. An additional k-means clustering step improves the biological features of WGCNA gene co-expression networks. BMC Syst Biol. 2017;11:47. doi: 10.1186/s12918-017-0420-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pei G, Chen L, Zhang W. WGCNA Application to Proteomic and Metabolomic Data Analysis. Methods Enzymol. 2017;585:135–158. doi: 10.1016/bs.mie.2016.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Samur MK. RTCGAToolbox: a new tool for exporting TCGA Firehose data. PLoS One. 2014;9:e106397. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fang SM, Hu BL, Zhou QZ, Yu QY, Zhang Z. Comparative analysis of the silk gland transcriptomes between the domestic and wild silkworms. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:60. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1287-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hochberg Y, Benjamini Y. More powerful procedures for multiple significance testing. Stat Med. 1990;9:811–818. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780090710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, Amin N, Schwikowski B, Ideker T. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dennis G Jr, Sherman BT, Hosack DA, Yang J, Gao W, Lane HC, Lempicki RA. DAVID: Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery. Genome Biol. 2003;4:P3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gene Ontology Consortium. The Gene Ontology (GO) project in 2006. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D322–D326. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Worby CA, Dixon JE. Sorting out the cellular functions of sorting nexins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:919–931. doi: 10.1038/nrm974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cullen PJ, Korswagen HC. Sorting nexins provide diversity for retromer-dependent trafficking events. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;14:29–37. doi: 10.1038/ncb2374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.You Y, Zhou C, Li D, Cao ZL, Shen W, Li WZ, Zhang S, Hu B, Shen X. Sorting nexin 10 acting as a novel regulator of macrophage polarization mediates inflammatory response in experimental mouse colitis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20630. doi: 10.1038/srep20630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen Y, Wu B, Xu L, Li H, Xia J, Yin W, Li Z, Shi D, Li S, Lin S, et al. A SNX10/V-ATPase pathway regulates ciliogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Cell Res. 2012;22:333–345. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qin B, He M, Chen X, Pei D. Sorting nexin 10 induces giant vacuoles in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:36891–36896. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608884200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang S, Hu B, You Y, Yang Z, Liu L, Tang H, Bao W, Guan Y, Shen X. Sorting nexin 10 acts as a tumor suppressor in tumorigenesis and progression of colorectal cancer through regulating chaperone mediated autophagy degradation of p21Cip1/WAF1. Cancer Lett. 2018;419:116–127. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2018.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Le Y, Zhang S, Ni J, You Y, Luo K, Yu Y, Shen X. Sorting nexin 10 controls mTOR activation through regulating amino-acid metabolism in colorectal cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:666. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0719-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gerber MM, Hampel H, Zhou XP, Schulz NP, Suhy A, Deveci M, Çatalyürek ÜV, Ewart Toland A. Allele-specific imbalance mapping at human orthologs of mouse susceptibility to colon cancer (Scc) loci. Int J Cancer. 2015;137:2323–2331. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cervantes-Anaya N, Ponciano-Gómez A, López-Álvarez GS, Gonzalez-Reyes C, Hernández-Garcia S, Cabañas-Cortes MA, Garrido-Guerrero JE, Villa-Treviño S. Downregulation of sorting nexin 10 is associated with overexpression of miR-30d during liver cancer progression in rats. Tumour Biol. 2017;39:1010428317695932. doi: 10.1177/1010428317695932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]