Abstract

With the absence of effective prophylactic vaccines and drugs against African trypanosomosis, control of this group of zoonotic neglected tropical diseases depends the control of the tsetse fly vector. When applied in an area-wide insect pest management approach, the sterile insect technique (SIT) is effective in eliminating single tsetse species from isolated populations. The need to enhance the effectiveness of SIT led to the concept of investigating tsetse-trypanosome interactions by a consortium of researchers in a five-year (2013–2018) Coordinated Research Project (CRP) organized by the Joint Division of FAO/IAEA. The goal of this CRP was to elucidate tsetse-symbiome-pathogen molecular interactions to improve SIT and SIT-compatible interventions for trypanosomoses control by enhancing vector refractoriness. This would allow extension of SIT into areas with potential disease transmission. This paper highlights the CRP’s major achievements and discusses the science-based perspectives for successful mitigation or eradication of African trypanosomosis.

Keywords: Glossina; Microbiota; Paratransgenesis; Vector competence; Trypanosoma-refractoriness, sterile insect technique; Hytrosaviridae

Background

Tsetse flies (Diptera; Glossinidae) transmit African trypanosomes across sub-Saharan Africa. These protozoan parasites are the causative agents of human and animal African trypanosomoses (HAT and AAT, respectively), which are neglected tropical diseases that are fatal if left untreated [1, 2]. A lack of effective prophylactic vaccines and drugs that target trypanosomes [3, 4] makes control of the tsetse vector an appealing alternative to reduce disease transmission. One attractive vector control method is the sterile insect technique (SIT), which is effective when included as a component of an area-wide integrated pest management (AW-IPM) approach [5–8]. SIT involves the mass production of sterilized male adults, which subsequently out-compete wild males in mating with wild virgin females in the field [9]. These matings are non-productive, eventually resulting in the decline and elimination of the target wild insect populations [10].

The successful and sustained eradication of Glossina austeni Newstead and AAT from Unguja Island in 1997 [7], in which SIT played a pivotal role, inspired African Governments to implement similar campaigns against tsetse on mainland Africa. SIT has also been employed to suppress G. palpalis gambiensis and G. tachinoides populations in Burkina Faso, G. p. palpalis in Nigeria [11, 12], and G. pallidipes in Ethiopia [13]. Challenges associated with improving SIT effectiveness include successful colony establishment [14], management of pathogenic infections that reduce colony fitness [15, 16] and compromised performance of field-released sterile males [17]. Importantly, the ability of released sterile males to vector trypanosomes increases the risk of transmitting disease in foci where trypanosomes are actively circulating. Furthermore, irradiation used for sterilization may negatively impact tsetse fitness (e.g. by damaging the tsetse host and its associated beneficial microbiota [18, 19].

The joint FAO/IAEA-sponsored coordinated research projects

To enhance the SIT programs, the Joint Division of FAO/IAEA initiated a five-year (2013–2018) Coordinated Research Project (CRP) on enhancing tsetse fly refractoriness to trypanosome infections [20]. Composed of 22 research teams from 18 countries, the CRP involved four Research Coordination Meetings (RCMs) to review the results, progress and plan future research activities.

This paper highlights the major achievements towards answering the following four key research questions of the CRP: (1) Can the elucidation of tsetse-trypanosome molecular interactions assist in the development of novel methods and approaches to reduce or prevent the transmission of trypanosomes by irradiated tsetse flies? (2) Are tsetse’s symbiome and the fly’s competence as a vector of trypanosomes affected by radiation? (3) Can tsetse symbionts be used to develop novel vector and disease control tools, complementary to the SIT? (4) Can the characterization of tsetse’s symbiome and viral pathogens improve the efficacy of SIT? [20]. Many other concepts that emerged while addressing the above-mentioned research questions were addressed during the course of the CRP.

Major objective of the CRP

The overall objective of the CRP was to elucidate the tsetse-symbiome-pathogen molecular interactions to improve SIT and SIT-compatible interventions. This effort was undertaken to reduce trypanosomosis by enhancing vector refractoriness, thus facilitating the expansion of SIT to areas where HAT-causing parasites are currently circulating in resident animals. The specific objectives and the expected output of this CRP are listed in Table 1 [See also Ref.#20]. The improved knowledge gained from achieving the objectives of the CRP is of significant interest to the FAO/IAEA and sub-Sahara African countries in their endeavor to control and ultimately eradicate tsetse and African trypanosomosis.

Table 1.

The Five-year (2013–2018) CRP objectives, outputs and achievements (published papers)

| Specific objectives | Expected output | Published papersa |

|---|---|---|

| (i). Elucidate tsetse-trypanosome interactions and understand determinants of vector competence. | (i). Molecular interplay of tsetse-trypanosomes characterized. (ii). Factors affecting trypanosome infections in tsetse determined. (iii). Tsetse vectorial competence assessed via comparative genomics and transcriptomics. |

[102–146]; ([21, 26, 43, 107, 147]) |

| (ii). Acquire better understanding of the physiology of tsetse-microbiota-pathogen tripartite interactions. | (i). Microbiota of multiple trypanosome-infected and uninfected tsetse species and hybrids determined. (ii). Trypanosome-microbiota interactions in model tsetse species and hybrids determined. (iii). Impacts of viral pathology on the tsetse symbionts determined. |

[42, 47, 53, 58, 59, 148–172]; ([44, 54, 72, 93, 173, 174]) |

| (iii). Determine effects of radiation in tsetse, its microbiota and pathogens. | (i). Effects of radiation on tsetse vectors, their symbionts and pathogens determined. (ii). Mutagenic effect of radiation on paratransgenesis determined. |

[175]; ([95, 99]) |

| (iv). Analyse SGHV-microbiota interactions in multiple tsetse species. | (i). Functional SGHV genes identified as candidates for developing antiviral mitigation strategy. (ii). Latency SGHV genes identified as tools for host interacting proteins. (iii). Mechanisms of SGHV’s escape from host defense response determined. (iv). SGHV haplotypes and evolution in lab-reared and wild tsetse fly populations determined. |

[75, 76, 79, 81, 82, 84, 176, 177]; ([28, 77, 78, 80, 83]) |

| (v). Develop novel symbiont-based, SIT-compatible anti-trypanosomiasis strategies. | (i). Wolbachia-based population suppression and/or replacement strategies assessed. (ii). Trypanosome-refractory paratransgenic tsetse lines developed. |

[94, 108, 178]; ([109]) |

a Articles in round brackets are published in the current issue of the BMC Special Issue. The remaining articles in this table have either been or are submitted for publication elsewhere during the five years (2013–2018) CRP period

Current status and achievements

During the course of the CRP (2013–2018) more than seventy scientific papers, detailing experimentally derived data related to achieving the project’s objectives, were published in peer reviewed journals. This special issue includes several of these papers, findings from which are briefly summarized in this introductory chapter along with the overall outcome of the project and future perspectives.

Tsetse species resolution

Correct taxonomic identification of insects is imperative for many reasons including the fact that studies conducted on different taxa may be reported by the same species (names), thus creating confusion. It is therefore important to properly identify field-captured tsetse species during characterization of their inhabiting microbial communities (including parasites, pathogens and symbionts). During the CRP, Augustinos and colleagues [21; this issue] evaluated the use of different molecular tools that can be used to efficiently and accurately distinguish distinct Glossina species using samples deriving from laboratory colonies and museum collections as well as all those collected in the field. The combined use of relatively inexpensive molecular genetic techniques, along with the identification of species specific microsatellites and mitochondrial and nuclear markers, will facilitate accurate identification of several tsetse species in the future.

Tsetse-microbiota-trypanosome interactions and determinants of vectorial competence

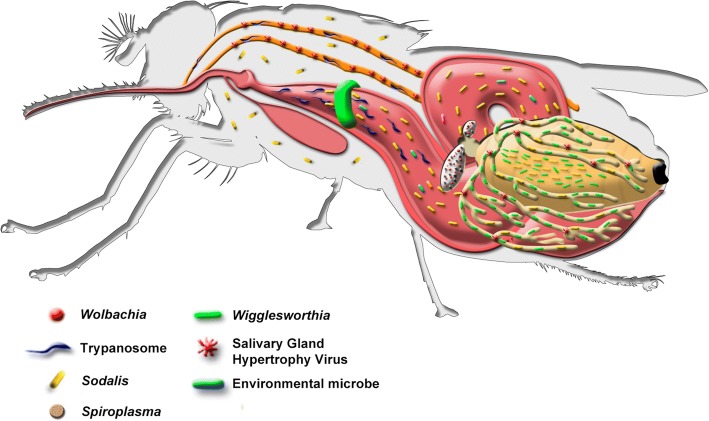

Figure 1 summarizes the interwoven associations and localization of the tsetse’s microbiota, which is comprised of the Wigglesworthia-Sodalis-Wolbachia complex, recently discovered Spiroplasma, environmentally acquired enteric bacteria, the salivary gland hypertrophy virus (SGHV) and the Trypanosoma parasite.

Fig. 1.

The tsetse fly and its associated microorganisms. Tsetse flies can harbor multiple microbes, including the bacterial endosymbionts obligate Wigglesworthia, facultative Sodalis, parasitic Wolbachia and Spiroplasma, as well as a taxonomically diverse population of environmentally acquired enteric bacteria, a virus (salivary gland hypertrophy virus, SGHV) and protozoan African trypanosomes. All tsetse harbor Wigglesworthia, while the presence of Sodalis, Wolbachia, Spiroplasma, SGHV and trypanosomes is fly population dependent. Wigglesworthia, Sodalis and SGHV are transmitted to developing intrauterine larval offspring via maternal milk secretions, while Wolbachia is transmitted through the germline. Spiroplasma’s mode of vertical transmission is currently unknown. Pathogenic trypanosomes are acquired by tsetse when they feed on an infected animal. The parasites must then undergo a complex development cycle in the fly before they can be successfully transmitted to a new host, where they cause disease. (This figure is adapted with permission from Aksoy et al., 2013) [179]

Trypanosome co-infections in tsetse flies

Molecular epidemiological surveys indicate that tsetse fly midguts, sampled from various HAT and AAT foci (including Fontem [22, 23] Campo and Bipindi [22, 24], Bafia [25] and Faro and Deo [26; this issue] in Cameroon) are infected with multiple trypanosome species. Application of nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) and/or trypanosome species-specific primers revealed that 53–82% of flies housed infections with trypanosome of a single species (T. brucei sl., T. congolense “forest” and “savannah” types, T. vivax and T. simiae), 18–47% were infected with two or three of the aforementioned species. In the Malanga HAT focus in Democratic Republic of Congo, 13.87% and 1.9% of G. p. palpalis had single and mixed trypanosome infections, respectively [27]. To assess the prevalence of trypanosome infection in a geographically broader area, Ouedraogo et al. [28; this issue] screened 3102 individual tsetse flies comprised of four species collected in five countries in west Africa. Results from this study indicate that trypanosome infections prevalence varied between tsetse species and location, but was on average substantial. In other words, infection prevalence ranged widely from 2.2–61.1% in flies sampled from different species in different locations. Furthermore, mixed infection was rarely observed (< 10%), and could be attributed to host specificity and/or preferences (human, domestic and wild animals) of particular tsetse species [29–32] and/or sensitivity of the PCR assay.

Modulations of tsetse gene expression during trypanosome infections

During SG infections, T. b. brucei suppresses the expression of the most abundant proteins in G. m. morsitans SGs, especially the proteins involved in the blood feeding process (e.g. Tsal1/2, TAg5, TSGF-1/2, 5’-Nuc, ADA and Spg3) [33]. This reduction in protein expression may significantly reduce fly feeding performance, consequently promoting vector competence via increase of the fly’s biting frequency. Further, the parasite upregulates expression of specific host proteins that are essential for parasite maturation, particularly proteins (e.g. CaMK, Serp-2, V-ATPases, and ArgK) involved in the regulation of stage-specific parasite differentiation [33, 34]. In response to the SG infection, tsetse overexpresses at least 15 immunity-related proteins [See Table 3 in Ref.#33]. In the midguts of G. pallidipes, which is more refractory to midgut colonization by trypanosomes compared to G. m. morsitans [35], T. b. brucei-challenge did not significantly modulate most of the genes (> 93%) in infected flies compared to uninfected controls [36]. However, whereas T. b. brucei induced expression of metabolism-associated genes in teneral flies (24 h post challenge), immunity-related and oxidative stress (ROS) genes were induced during late infection stages (48 h post challenge) [36]. Induction of expression of immunity and ROS genes is partially implicated in trypanosome-refractoriness in G. m. morsitans [37]. Notably, unlike in G. m. morsitans, in which only a small proportion of midgut infections progress to the SG, all G. pallidipes with trypanosome gut infections end up hosting mature SG infections [35]. Together, these data are applicable in designing strategies to interfere with metacyclogenesis and transmission of the mammalian-infective metacyclic (MT) parasites in the SGs of G. pallidipes. The SG tissue bottleneck (in trypanosome transmission) represents a vulnerable and attractive intervention point to enhance natural tsetse refractoriness to trypanosomes or to reduce the vectorial competence of the sterile males used in SIT campaigns.

Role of Sodalis in the establishment of trypanosome infections in tsetse midguts

Sodalis glossinidius, tsetse’s facultative endosymbiont, may modulate the ability of trypanosomes to establish an infection in tsetse’s midgut. However, the mechanism(s) that underlies this association is poorly understood [38–40]. This CRP addressed this knowledge gap by further exploring the relationship between Sodalis and trypanosome infection in tsetse. Geiger et al. [41] observed a correlation between specific Sodalis genotypes and tsetse’s ability to establish trypanosomes infection.

Hamidou et al. [42] demonstrated that Sodalis-hosted prophages also mediate trypanosome infection establishment by affecting Sodalis densities. However, certain studies on field-caught tsetse did not indicate any strong associations between Sodalis densities and trypanosome infections [26; this issue, 43; this issue]. In addition, a correlation between trypanosome infection and Sodalis presence observed in Kenya [43; this issue] was weak or nonexistent. However, the authors thought that tsetse-trypanosome-microbiota interactions could be influenced by other factors such as tsetse’s ecology and community compositions, but only in some species of trypanosomes. However, Griffith et al., [44; this issue] found that Sodalis densities were significantly higher in trypanosome-infected, wild-caught flies compared to their uninfected counterparts. Additionally, other confounding factors may indirectly affect vectorial competence, including tsetse flies age, sex, habitat, species of trypanosome, and Sodalis genotypes and their modulation of the host’s immune system [43, this issue]. These factors may influence Sodalis densities, which may indirectly impact trypanosome prevalence within tsetse and the fly’s vectorial competence for trypanosome transmission.

Insights into tsetse-microbiota-pathogen tripartite interactions

ᅟ

Tsetse symbionts

Taxonomic composition of microbial communities housed in the gut of wild tsetse

Enteric microbes impact several aspects of their host’s physiology [45]. In tsetse, the obligate mutualist Wigglesworthia mediates numerous aspects of the fly’s physiology, including nutrition, reproduction and immune system maturation and function [46–48]. Over the course of this CRP, researchers performed studies to characterize the taxonomic composition of environmentally acquired bacteria housed in the gut of field-captured and colonized tsetse. This information is an important prelude to understanding how this population of microbes impacts tsetse’s fitness and susceptibility to trypanosome infection. Using culture dependent and independent techniques, prominent bacterial taxa found in guts from field captured tsetse included Serratia, Enterobacter, Enterococcus, Acinetobacter, Providencia, Sphingobacterium, Chryseobacterium, Lactococcus, Staphylococcus, and Pseudomonas, Bacillus, Mesorhizobium, Paracoccus, Microbacterium, Micrococcus, Arthrobacter, Corynobacterium, Curtobacterium, Vagococcus, and Dietzia spp. ([44, 49–54]; this issue). The sources and mechanisms by which tsetse flies acquire this diverse enteric microbiota remain unclear. However, tsetse hosts from specific ecosystems could differ in their microbial diversities [55]. Flies could ingest bacteria present on host skin when probing for a blood meal [56], or host blood may contain bacteria that are ingested by flies during feeding on a septic host. Identification of diverse bacteria in tsetse tissues that also house trypanosomes raises the question whether these bacteria influence trypanosome infections. Environmentally acquired bacteria found in the gut of other disease vectors (i.e., Anopheles gambiae) exhibit direct anti-parasitic properties [57]. As such, tsetse’s gut microbiota should be explored in more detail to determine if bacteria that exhibit anti-trypanosomal properties are present in the fly’s gut.

Discovery and characterization of Spiroplasma, a potential fourth symbiont of tsetse

One of the major achievements of this CRP is the discovery of Spiroplasma as a fourth endosymbiont (in addition to Wigglesworthia, Sodalis, and Wolbachia) in some wild and laboratory-reared tsetse populations [58, 59]. While the function of this bacterium in tsetse is currently unknown, it likely to impact colony fitness. However, in Drosophila, Spiroplasma is a maternally [60] and horizontally transmitted mutualist [61]. Some lineages of Spiroplasma confer their hosts with important traits, including defense against pathogens (e.g. parasites and bacteria), either singly or in associations with other symbionts such as Wolbachia [62–65]. The poorly understood mechanism(s) of Spiroplasma-Wolbachia associations presents an intriguing research topic, given that Wolbachia (found mainly in reproductive organs) and Spiroplasma (resides primarily in the hemolymph, but can also invade other tissues such as ovaries, fat body and SGs) exhibit similar tissue tropisms. Research on the Glossina-Spiroplasma association is required to determine if the bacterium presents commensal, mutualist or pathogenic phenotypes in the fly. Additionally, it will be important to determine the relationship between Spiroplasma and other constituents of tsetse’s microbiota, including bacterial symbionts, viral pathogens and trypanosomes. Finally, studies should be performed to determine if Spiroplasma can be utilized to develop novel symbiont-based strategies aimed at blocking trypanosome transmission.

Role of Wolbachia in tsetse speciation and generation of fertile hybrid tsetse colonies

Symbiont-induced cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI) acts as an efficient post-mating barrier to hybrid formation, making it an important parameter in preserving species borders [66–69]. In tsetse, Wolbachia efficiently triggers CI within [70] and between species [71]. During the CRP, Wolbachia related research focused on two main topics: 1) the development of diagnostic tools sensitive to detect low titer Wolbachia infections in tsetse species, and 2) exploration of Wolbachia’s role in tsetse speciation. In relation to the first topic, Schneider et al. [72; this issue], compared classic endpoint PCR with high-sensitivity blot-PCR and demonstrated that the latter technique facilitates more sensitive detection of low-titer Wolbachia in the morsitans and palpalis groups than does classic endpoint PCR. In addition, the authors used a high-end Stellaris® rRNA-FISH based technique to localize Wolbachia in situ in high and low-titer Glossina species, and demonstrated that with this highly sensitive method, even low amounts of Wolbachia can be traced in specific tissues. The results also highlight that more tissues and organs than previously recorded are infested with Wolbachia in subspecies of the morsitans and palpalis groups. The novel, highly sensitive molecular Wolbachia detection tools developed during the CRP [72; this issue] should expedite further investigations on the tsetse hybrid colonies.

With regard to Wolbachia’s role in tsetse speciation, previously published data indicate that mating between Wolbachia-free G. morsitans females and wild type G. morsitans males results in significantly reduced larval deposition and adult eclosion rates [70]. Similarly, mating between wild type G. morsitans and G. centralis triggers high CI levels due to the presence of two incompatible Wolbachia strains [71]. However, premating barriers to hybrid formation are rather weak or completely absent, as members of various Glossina species mate readily [73]. Nevertheless, the negative effects of CI led to the consideration of generating tsetse hybrids for population control [74]. This consideration is based on the assumption that among artificially created hybrids between closely related Glossina species, males are post-zygotically incompatible with both parental species due to their natural hybrid sterility. Such pseudo-sterile tsetse males can be complementary to the SIT programs. Experiments performed during the CRP demonstrated that knockdown of native Wolbachia in G. m. morsitans males prior to their mating with G. m. centralis females results in successful establishment of a hybrid line, which is now maintained in the IPCL tsetse production facility in Seibersdorf, Austria (unpublished data). Therefore, prior to employing hybrid flies to existing SIT programs, further investigations are necessary to determine how symbiont status and mating competence are affected in the hybrid background, and whether the hybrids and wild type flies are equally fit.

Tsetse fly pathogens

In addition to microbial communities associated with tsetse flies, pathogens such as the SGHV (Hytrosaviridae) and entomopathogenic fungi (EPF) infect tsetse flies and hence affect fly fitness both in insect mass rearing facilities and in the field. During the CRP, research was conducted to gain a better understanding on the impact of these pathogens on tsetse fly fitness and susceptibility to trypanosomes.

Salivary gland hypertrophy viruses

Pathobiology of GpSGHV haplotypes and the prospects for integrated antiviral strategies

Over the course of the CRP, the following topics related to SGHV were investigated: 1) improvement of virus control strategies [75], 2) explore genomic differences between virus isolates [76], 3) virus host range [77], 4) the impact of virus infection on tsetse fitness, 5) genetic diversity of field collected viral isolates, and 6) the impact of virus infection on the expression of tsetse immune genes. Comparative analyses of the Ethiopian and Ugandan GpSGHV strains [76] suggest that the differential virus-pathologies (i.e. outbreaks of the salivary gland hypertrophy symptoms, SGH) in G. pallidipes colonies are due to factors such as differences in viral gene contents, host genetics and ecologies, and virus-host co-evolutionary histories [78]; this issue. GpSGHV pathological effects and the host’s response to the virus infection vary amongst different Glossina species. For instance, in G. pallidipes, GpSGHV infection results in significant upregulation of host genes associated with pathways promoting viral infection compared to upregulation of genes associated with antiviral responses in virus-infected G. m. morsitans [79]. We now have clues that more GpSGHV strains exist in multiple Glossina species, and that G. pallidipes may influence GpSGHV evolution [78, 80]; this issue. Susceptibilities of tsetse to GpSGHV infections, and the negative impacts of viral infections on the fly’s fecundity, adult eclosion and survival, differ amongst different fly species [77, 81]; this issue. The narrow GpSGHV host range (only in Glossina species) and lack of overt SGH in the majority of tsetse hosts do not preclude implementing precautionary antiviral measures in tsetse production facilities that rear multiple species [15, 16, 78, 82].

Insights into the roles of tsetse immunity during symptomatic GpSGHV infections in lab-bred tsetse colonies

We have ascertained that GpSGHV infection provokes the RNA interference (RNAi) defense response, as evidenced by significant upregulation of the expression of key RNAi pathway genes (Ago-1, Ago-2 and Dcr-2) in virus-injected flies (asymptomatically infected) compared to the non-infected flies [83; this issue]. These data imply that both siRNA and miRNA pathways (two of the RNAi machinery pathways) provide antiviral defense in asymptomatic infected flies, but the pathways are highly compromised during symptomatic infections. The third RNAi machinery pathway (piRNA pathway) appeared not to be involved in tsetse’s defense mechanism against GpSGHV, as virus infection did not affect the expression of Ago-3 gene, a key gene in the piRNA pathway [83]. In addition to the RNAi, we have indications that GpSGHV infection alters the host miRNA profile in G. pallidipes, thus indicating possible functional importance of miRNAs in symptomatic infections [84; MS in Prep.]. Notably, the majority of the upregulated miRNAs were predicted to target over 700 host mRNAs, of which 150 mRNAs were immune-related. miRNA expression profiles are also modulated by the insect microbiota, and may therefore contribute to the outcomes of virus infection as has been demonstrated in the dengue mosquito vector Aedes aegypti [85]. Recent data suggest that the absence (or low densities) of Wolbachia positively correlates with SGHV outbreaks in G. pallidipes colonies compared with other Glossina species that rarely exhibit overt SGH symptoms [86]. Whether differences in Wolbachia prevalence in tsetse species is linked to differences in GpSGHV infections (e.g. via modulations of miRNAs) requires further investigations.

Entomopathogenic fungi

EPF have been proposed as potential mosquito control agents [87]. The EPF Metarhizium anisopliae (Metsch.) Sorok may suppress wild tsetse populations when autodisseminated from devices mounted on pyramidal traps [88]. Furthermore, horizontal transmission of the EPF was demonstrated between M. anisopliae-infected G. pallidipes and fungus-free flies during mating [89]. These characteristics make M. anisopliae a suitable candidate to be combined with SIT. Prior to causing death, fungal infection can significantly reduce tsetse feeding and reproduction [90–92]. Therefore, the complementary action of EPF on reducing tsetse’s blood feeding and reproduction capacity, and potential effects on trypanosome development within the vector, could influence disease epidemiology and transmission. During the CRP, Wamiti et al. [93; this issue] conducted research focused on determining the impact of EPF on trypanosome infection. The results indicate that infection of G. f. fuscipes with M. anisopliae resulted not only in significant reduction in T. congolense titers, but also hindered the fly’s vectorial competence (ability to acquire and transmit trypanosomes to mice). The precise mechanism(s) underlying the fungal-mediated anti-trypanosome impacts remain to be elucidated.

Effects of irradiation on tsetse, its microbiota and trypanosome infections

One of the major objectives of this CRP was to investigate the possibility of combining paratransgenesis with SIT to control tsetse population size and simultaneously reduce their vector competence. Paratransgenesis involves genetically modifying tsetse’s commensal endosymbiont Sodalis so that it produces anti-trypanosome factors. Modified Sodalis are reintroduced into female flies, which subsequently present a trypanosome refractory phenotype ([94]; see section “Prospects of developing symbiont-based anti-trypanosome strategies” below for more details). As sterile males are produced via exposure to irradiation, the impact of this treatment on modified Sodalis is crucial for the implementation of the combined approach. To this end, Demirbaş-Uzel et al. [95; this issue] investigated the correlation between tsetse developmental stage (22- day old pupae, 29-day old pupae and 7-day old adults) at the time of radiation exposure and impact on Sodalis density. The results indicate that irradiation of seven-days old G. m. morsitans adults significantly reduced Sodalis densities. Furthermore, the recovery of Sodalis densities was significantly higher in the adults that emerged from puparia that had been irradiated on day 22 post larviposition as compared to the flies that had been irradiated as adults [95]. Results also indicate that irradiation of puparia on day 22 post larviposition has no effect on the vectorial capacity of the emerged males to transmit trypanosomes. The recovery of Sodalis titers in sterile males opens the door to combine paratransgenesis with SIT for tsetse control. In addition, pupal irradiation is operationally advantageous in terms of handling and transportation compared to adult irradiation [96].

Field released sterile males must efficiently identify and mate with wild females. Therefore, one component of the CRP investigated the effects of various doses of ionizing radiation on tsetse cuticular hydrocarbon (CHCs; e.g. n-alkanes, alkenes and methyl-branched hydrocarbons) profiles. CHCs act as sex pheromones for species, sex, and mate recognition in Drosophila [97] and tsetse [98]. Engl et al. [99; this issue] investigated the impact of bacterial symbionts and irradiation on tsetse CHC profiles. They discovered that antibiotic-mediated knockdown of tsetse’s indigenous microbiota significantly reduced tsetse’s CHCs profiles and correspondingly impacted mate choice. [99; this issue]. However, no significant differences in CHC profiles were observed between irradiated and non-irradiated G. m. morsitans flies [99]. These findings call for further research into the roles of microbiota (e.g. Wigglesworthia) in tsetse’s mating behavior (in terms of CHC synthesis), and how the effects of irradiation on the microbiota can be reversed in irradiated males before inundative releases during SIT applications.

Prospects of developing symbiont-based anti-trypanosome strategies

The development of trypanosome-refractory sterile males would make SIT much less controversial, particularly when applied in trypanosome-endemic locations [20]. The viviparous reproduction of tsetse is not directly amenable to germ-line transformation for the purpose of ectopically expressing trypanocidal transgenes in an effort to reduce the fly’s vector competence [100]. However, trypanosome-refractoriness can be indirectly conferred to tsetse via paratransgenesis, whereby genetically engineered symbionts express molecules that block trypanosome development and/or transmission [101] (Fig. 2). This approach works in triatome bugs [102] and mosquitoes [103, 104]. Sodalis is an ideal bacterium for expressing effector molecules in paratransgenic tsetse because it (i) resides in close proximity to trypanosomes; (ii) can be cultured and engineered in vitro; (iii) can be re-introduced into tsetse after transformations; (iv) is maternally transmitted to fly progenies, and (v) is rigorously restricted to the tsetse host niche [105]. Engineered Sodalis can express and release significant amounts of functional nanobodies that target trypanosome surface epitopes in different tsetse tissues [94, 106]. Moreover, improved strategies have been developed to: (i) identify and determine population dynamics of tsetse species in a particular area [107; this issue], (ii) establish stable chromosomal expression in Sodalis allowing strong and constitutive expression of anti-trypanosome compounds [108], and (iii) sustainably colonize tsetse and its subsequent generations with genetically modified Sodalis through microinjection into third-instar larvae [109; this issue]. Sodalis-mediated inhibition of parasite development in paratransgenic tsetse remains to be demonstrated.

Fig. 2.

Overview of the current status on tsetse paratransgenesis. Strategies have been developed for i) isolation and in vitro cultivation of Sodalis glossinidius, ii) establishing stable chromosomal expression in Sodalis allowing strong and constitutive expression of anti-trypanosome compounds in the absence of antibiotic selection and iii) the sustainable colonization of tsetse fly and its subsequent generations with genetically modified Sodalis through microinjection of the bacterium into third-instar larvae [109; this issue]. Taken together, the necessary technology for application of Sodalis as a delivery system in tsetse paratransgenic has been developed, but the Sodalis-mediated inhibition of parasite development in the insect host is yet to be demonstrated. The final main bottleneck remains the identification of a highly potent and stable trypanolytic component effectively blocking parasite transmission by the fly without impairing symbiont and vector fitness

Conclusions

A large body of information related to enhancing tsetse fly refractoriness to trypanosome infections was acquired over the course of this CRP. However, many challenges and questions remain, which include, but are not limited to 1) developing more efficient tools to correctly classify field captured tsetse flies, 2) further deciphering the functional association between tsetse’s microbiota (including environmentally acquired enteric bacteria, endosymbiotic microbes and pathogenic or symbiotic viruses and fungi) and the fly’s physiology and trypanosome vector competency, 3) optimizing SIT irradiation protocols so that the treatment has a minimal effect of tsetse/endosymbiont fitness, and 4) maximizing the efficiency of tsetse paratransgenesis. Theoretical and technical knowledge acquired from experiments performed using the model tsetse species, G. m. morsitans (and its associated microorganisms), serves as a foundation for similar studies in other, more epidemiologically relevant tsetse species.

This CRP served as a platform for scientists from African, European and North American countries to interact, exchange ideas and develop long-term, mutually beneficial collaborations. Additionally, the extensive collaborations established during the CRP will continue in a new five-year CRP, which will address various issues related to the improvement of colony management in tsetse mass rearing for SIT applications (http://www-naweb.iaea.org/nafa/ipc/crp/new-crps-ipc.html). Finally, African members of this CRP can disseminate knowledge and expertise acquired to additional research communities in other tsetse-endemic regions of sub-Saharan Africa and to national authorities to promote the novel insights in tsetse and trypanosomosis control.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Geoffrey M. Attardo from the University of California, Davis, for his kind effort in preparing Fig. 1. This work was funded by the Joint FAO/IAEA Division of Nuclear Techniques in Food and Agriculture, Vienna, Austria (Coordinate Research Project No. D42015). Meki IK is a recipient of a sandwich PhD grant from Wageningen University. All the colleagues who participated in the CRP and contributed to the review of the articles in this Special Issue are cordially acknowledged.

Funding

This work and the publication was funded by the Joint FAO/IAEA Division of Nuclear Techniques in Food and Agriculture, IAEA (CRP No.: D4.20.15) Vienna, Austria.

About this supplement

This article has been published as part of BMC Microbiology Volume 18 Supplement 1, 2018: Enhancing Vector Refractoriness to Trypanosome Infection. The full contents of the supplement are available online at https://bmcmicrobiol.biomedcentral.com/articles/supplements/volume-18-supplement-1.

Abbreviations

- 16S rRNA

16S ribosomal RNA

- 5’-Nuc

5′-nucleotidase-related saliva protein

- ADA

Adenine deaminase

- Ago

Argonaute

- AMP

Antimicrobial peptide

- ArgK

Arginine kinase

- AW-IPM

Area-wide integrated pest management

- BSF

Bloodstream form

- CaMK

Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase

- CHCs

Cuticular hydrocarbons

- CI

Cytoplasmic incompatibility

- CRP

Coordinated research project

- Dcr

Dicer

- DEG

Differentially expressed gene

- DENV

Dengue virus

- dsRNA

Double-stranded RNA

- EPF

Entomopathogenic fungus

- FAO

Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations

- GpSGHV

Glossina pallidipes salivary gland hypertrophy virus

- HGT

Horizontal gene transfer

- IAEA

International Atomic Energy Agency

- Imd

Immune deficiency

- MdSGHV

Musca domestica salivary gland hypertrophy virus

- miRNA

Micro RNA

- MLST

Multi locus sequence typing

- MT parasites

Mammalian-infective metacyclic parasites

- PGRP-LB

Peptidoglycan-recognition protein LB

- piRNA

Piwi-interacting RNA

- RCM

Research Coordination Meetings

- RNAi

RNA interference

- RNA-Seq

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) sequencing

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- SG

Salivary gland

- siRNA

Short interfering RNA

- SIT

Sterile insect technique

- Spg3

5′-nucleotidase-related SG protein-3

- TAg5

Salivary antigen-5-protein

- Tbb

Trypanosoma brucei brucei

- Tbg

Trypanosoma brucei gambiense

- Tbr

Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense

- Tc

Trypanosoma congolense

- Tsal1/2

Tsetse salivary gland proteins 1 & 2

- TSGF-1/2

Tsetse salivary growth factors 1 & 2

- V-ATPase

Vacuolar-type H+ -ATPase

Authors’ contributions

HK, IM, DS, DL, FK, AG and GD-U wrote the first draft of the manuscript. HK and AA coordinated the writing of the manuscript. JV, AI, SK, FN, FW, MI, and BW contributed to manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Henry M Kariithi, Email: henry.kariithi@kalro.org.

Irene K Meki, Email: i.meki@iaea.org.

Daniela I Schneider, Email: daniela.schneider@yale.edu.

Linda De Vooght, Email: ldevooght@itg.be.

Fathiya M Khamis, Email: fkhamis@icipe.org.

Anne Geiger, Email: anne.geiger@ird.fr.

Guler Demirbaş-Uzel, Email: g.demirbas-uzel@iaea.org.

Just M Vlak, Email: just.vlak@wur.nl.

ikbal Agah iNCE, Email: agah.ince@acibadem.edu.tr.

Sorge Kelm, Email: skelm@uni-bremen.de.

Flobert Njiokou, Email: njiokouf@yahoo.com.

Florence N Wamwiri, Email: f.wamwiri@gmail.com.

Imna I Malele, Email: maleleimna@gmail.com.

Brian L Weiss, Email: brian.weiss@yale.edu.

Adly M M Abd-Alla, Email: a.m.m.abd-alla@iaea.org.

References

- 1.Mattioli RC, Feldmann U, Hendrickx G, Wint W, Jannin J, Slingenbergh J. Tsetse and trypanosomiasis intervention policies supporting sustainable animal-agricultural development. J Food Agric Environ. 2004;2:310–314. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cecchi G, Mattioli RC, Slingenbergh J, De La Rocque S. Land cover and tsetse fly distributions in sub-Saharan Africa. Med Vet Entomol. 2008;22:364–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2008.00747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barrett MP, Vincent IM, Burchmore RJ, Kazibwe AJ, Matovu E. Drug resistance in human African trypanosomiasis. Future Microbiol. 2011;6:1037–1047. doi: 10.2217/fmb.11.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geerts S, Holmes PH, Eisler MC, Diall O. African bovine trypanosomiasis: the problem of drug resistance. Trends Parasitol. 2001;17:25–28. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4922(00)01827-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schofield CJ, Kabayo JP. Trypanosomiasis vector control in Africa and Latin America. Parasit Vectors. 2008;1:24. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-1-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vreysen MJ. Prospects for area-wide integrated control of tsetse flies (Diptera: Glossinidae) and trypanosomosis in sub-Saharan Africa. Rev Soc Entomológica Argent. 2006;65:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vreysen MJ, Saleh K, Mramba F, Parker A, Feldmann U, Dyck VA, et al. Sterile insects to enhance agricultural development: the case of sustainable tsetse eradication on Unguja Island, Zanzibar, using an area-wide integrated pest management approach. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e2857. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vreysen MJB. Principles of area-wide integrated tsetse fly control using the sterile insect technique. Méd Trop. 2001;61:397–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vreysen MJB, Saleh KM, Lancelot R, Bouyer J. Factory tsetse flies must behave like wild flies: a prerequisite for the sterile insect technique. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e907. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Molyneux DH, Hopkins DR, Zagaria N. Disease eradication, elimination and control: the need for accurate and consistent usage. Trends Parasitol. 2004;20:347–351. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olandunmade MA, Feldmann U, Takken W, Tenabe SO, Hamann HJ, Onah J, et al. Eradication of Glossina palpalis palpalis (Robineau-Desvoidy) (Diptera: Glossinidae) from agropastoral land in Central Nigeria by means of the sterile insect technique. In: Offori ED, Van de Vloedt AMV, et al., editors. Sterile insect technique for tsetse control and eradication. Vienna: International Atomic Energy Agency; 1990. pp. 5–23. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Politzar H, Merot P, Brandl FE. Experimental aerial release of sterile males of Glossina palpalis gambiensis and of Glossina tachinoides in a biological control operation. Rev D’élevage Méd Vét Pays Trop. 1984;37:198–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kebede A, Ashenafi H, Daya T. A review on sterile insect technique (SIT) and its potential towards tsetse eradication in Ethiopia. Adv Life Sci Technol. 2015;37:24–44. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Enserink M. Welcome to Ethiopia’s fly factory. Science. 2007;317:310. doi: 10.1126/science.317.5836.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abd-Alla AMM, Kariithi HM, Mohamed AH, Lapiz E, Parker AG, Vreysen MJB. Managing hytrosavirus infections in Glossina pallidipes colonies: feeding regime affects the prevalence of salivary gland hypertrophy syndrome. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61875. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kariithi HM, van Oers MM, Vlak JM, Vreysen MJ, Parker AG, Abd-Alla AM. Virology, epidemiology and pathology of Glossina hytrosavirus, and its control prospects in laboratory colonies of the tsetse fly, Glossina pallidipes (Diptera; Glossinidae) Insects. 2013;4:287–319. doi: 10.3390/insects4030287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Terblanche JS, Chown SL. Factory flies are not equal to wild flies. Science. 2007;317:1678. doi: 10.1126/science.317.5845.1678b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lauzon CR, Potter SE. Description of the irradiated and nonirradiated midgut of Ceratitis capitata Wiedemann (Diptera: Tephritidae) and Anastrepha ludens Loew (Diptera: Tephritidae) used for sterile insect technique. JPest Sci. 2012;85:217–226. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Engel P, Moran NA. The gut microbiota of insects: diversity in structure and function. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2013;37:699–735. doi: 10.1111/1574-6976.12025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abbeele VDJ, Bourtzis K, Weiss B, Cordón-Rosales C, Miller W, Abd-Alla AMM, et al. Enhancing tsetse fly refractoriness to trypanosome infection: a new IAEA coordinated research project. J Invertebr Pathol. 2013;112:S142–S147. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2012.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Augustinos A, Meki IK, Demirbas-Uzel G, Ouedraogo GMS, Saridaki A, Tsiamis G, et al. Nuclear and Wolbachia-based multimarker approach for the rapid and accurate. BMC Microbiol. 2018. 10.1186/s12866-018-1295-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Morlais I, Grebaut P, Bodo JM, Djoha S, Cuny G, Herder S. Detection and identification of trypanosomes by polymerase chain reaction in wild tsetse flies in Cameroon. Acta Trop. 1998;70:109–117. doi: 10.1016/S0001-706X(98)00014-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simo G, Njitchouang GR, Njiokou F, Cuny G, Asonganyi T. Trypanosoma brucei s.l.: microsatellite markers revealed high level of multiple genotypes in the mid-guts of wild tsetse flies of the Fontem sleeping sickness focus of Cameroon. Exp Parasitol. 2011;128:272–278. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2011.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farikou O, Njiokou F, Mbida Mbida JA, Njitchouang GR, Djeunga HN, Asonganyi T, et al. Tripartite interactions between tsetse flies, Sodalis glossinidius and trypanosomes - an epidemiological approach in two historical human African trypanosomiasis foci in Cameroon. Infect Genet Evol. 2010;10:115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simo G, Fongho P, Farikou O, Ndjeuto-Tchouli PIN, Tchouomene-Labou J, Njiokou F, et al. Trypanosome infection rates in tsetse flies in the “silent” sleeping sickness focus of Bafia in the Centre region in Cameroon. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:528. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-1156-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kame-Ngasse G, Njiokou F, Melachio-Tanekou TT, Farikou O, Simo G, Geiger A. Prevalence of symbionts and trypanosome infections in tsetse flies of two villages of the “Faro and Déo” division of the Adamawa Region of Cameroon. BMC Microbiol. 2018; 10.1186/s12866-018-1286-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Simo G, Silatsa B, Flobert N, Lutumba P, Mansinsa P, Madinga J, et al. Identification of different trypanosome species in the mid-guts of tsetse flies of the Malanga (Kimpese) sleeping sickness focus of the Democratic Republic of Congo. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:201. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ouedraogo GMS, Demirbaş-Uzel G, Rayaisse J-B, Traore A, Augustinos AA, Parker AG, et al. Prevalence of trypanosomes, salivary gland hypertrophy virus and Wolbachia in wild populations of tsetse flies from West Africa. BMC Microbiol. 2018; 10.1186/s12866-018-1287-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Njiokou F, Simo G, Nkinin S, Laveissière C, Herder S. Infection rate of Trypanosoma brucei sl, T. vivax, T. congolense “forest type”, and T. simiae in small wild vertebrates in South Cameroon. Acta Trop. 2004;92:139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simo G, Njiokou F, Mbida JM, Njitchouang G, Herder S, Asonganyi T, et al. Tsetse fly host preference from sleeping sickness foci in Cameroon: epidemiological implications. Infect Genet Evol. 2008;8:34–39. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Njiokou F, Simo G, Mbida Mbida A, Truc P, Cuny G, Herder S. A study of host preference in tsetse flies using a modified heteroduplex PCR-based method. Acta Trop. 2004;91:117–120. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nimpaye H, Njiokou F, Njine T, Njitchouang G, Cuny G, Herder S, et al. Trypanosoma vivax, T. congolense “forest type” and T. simiae: prevalence in domestic animals of sleeping sickness foci of Cameroon. Parasite. 2011;18:171. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2011182171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kariithi HM, Boeren S, Murungi EK, Vlak JM, Abd-Alla AMM. A proteomics approach reveals molecular manipulators of distinct cellular processes in the salivary glands of Glossina m. morsitans in response to Trypanosoma b. brucei infections. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:424. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1714-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Den Abbeele J, Caljon G, De Ridder K, De Baetselier P, Coosemans M. Trypanosoma brucei modifies the tsetse salivary composition, altering the fly feeding behavior that favors parasite transmission. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000926. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peacock L, Ferris V, Bailey M, Gibson W. The influence of sex and fly species on the development of trypanosomes in tsetse flies. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1515. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bateta R, Wang J, Wu Y, Weiss BL, Warren WC, Murilla GA, et al. Tsetse fly (Glossina pallidipes) midgut responses to Trypanosoma brucei challenge. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:614. doi: 10.1186/s13071-017-2569-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aksoy E, Vigneron A, Bing X, Zhao X, O’Neill M, Wu Y, et al. Mammalian African trypanosome VSG coat enhances tsetse’s vector competence. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2016;113:6961–6966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1600304113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maudlin I, Ellis DS. Association between intracellular rickettsial-like infections of midgut cells and susceptibility to trypanosome infection in Glossina spp. Z Für Parasitenkd. 1985;71:683–687. doi: 10.1007/BF00925601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Welburn SC, Maudlin I. Tsetse–trypanosome interactions: rites of passage. Parasitol Today. 1999;15:399–403. doi: 10.1016/S0169-4758(99)01512-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dale C, Welburn S. The endosymbionts of tsetse flies: manipulating host–parasite interactions. Int J Parasitol. 2001;31:628–631. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(01)00151-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Geiger A, Ravel S, Mateille T, Janelle J, Patrel D, Cuny G, et al. Vector competence of Glossina palpalis gambiensis for Trypanosoma brucei s.l. and genetic diversity of the symbiont Sodalis glossinidius. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;24:102–109. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hamidou Soumana I, Loriod B, Ravel S, Tchicaya B, Simo G, Rihet P, et al. The transcriptional signatures of Sodalis glossinidius in the Glossina palpalis gambiensis flies negative for Trypanosoma brucei gambiense contrast with those of this symbiont in tsetse flies positive for the parasite: possible involvement of a Sodalis-hosted prophage in fly Trypanosoma-refractoriness? Infect Genet Evol. 2014;24:41–56. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Channumsin M, Ciosi M, Masiga D, Turner CMR, Mable BK. Sodalis glossinidius presence in wild tsetse is only associated with presence of trypanosomes in complex interactions with other tsetse-specific factors BMC Microbiol. 2018; 10.1186/s12866-018-1285-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Griffith BC, Weiss BL, Aksoy E, Mireji PO, Auma JE, Wamwiri FN, et al. Analysis of the gut-specific microbiome from field-captured tsetse flies, and its relevance to host trypanosome vector competence. BMC Microbiol. 2018; 10.1186/s12866-018-1284-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Klepzig KD, Adams AS, Handelsman J, Raffa KF. Symbioses: a key driver of insect physiological processes, ecological interactions, evolutionary diversification, and impacts on humans. Environ Entomol. 2009;38:67–77. doi: 10.1603/022.038.0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang J, Weiss BL, Aksoy S. Tsetse fly microbiota: form and function. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2013;3:6. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2013.00069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bing X, Attardo GM, Vigneron A, Aksoy E, Scolari F, Malacrida A, et al. Unravelling the relationship between the tsetse fly and its obligate symbiont Wigglesworthia: transcriptomic and metabolomic landscapes reveal highly integrated physiological networks. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2017;284:20170360. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2017.0360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Benoit JB, Vigneron A, Broderick NA, Wu Y, Sun JS, Carlson JR, et al. Symbiont-induced odorant binding proteins mediate insect host hematopoiesis. elife. 2017;6:e19535. doi: 10.7554/eLife.19535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Geiger A, Fardeau ML, Falsen E, Ollivier B, Cuny G. Serratia glossinae sp. nov., isolated from the midgut of the tsetse fly Glossina palpalis gambiensis. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2010;60:1261–1265. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.013441-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Geiger A, Fardeau ML, Grebaut P, Vatunga G, Josenando T, Herder S, et al. First isolation of Enterobacter, Enterococcus, and Acinetobacter spp. as inhabitants of the tsetse fly (Glossina palpalis papalis) midgut. Infect Genet Evol. 2009;9:1364–1370. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2009.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Geiger A, Fardeau ML, Njiokou F, Joseph M, Asonganyi T, Ollivier B, et al. Bacterial diversity associated with populations of Glossina spp. from Cameroon and distribution within the campo sleeping sickness focus. Microb Ecol. 2011;62:632–643. doi: 10.1007/s00248-011-9830-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lindh JM, Lehane MJ. The tsetse fly Glossina fuscipes fuscipes (Diptera: Glossina) harbors a surprising diversity of bacteria other than symbionts. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2011;99:711–720. doi: 10.1007/s10482-010-9546-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aksoy E, Telleria EL, Echodu R, Wu Y, Okedi LM, Weiss BL, et al. Analysis of multiple tsetse fly populations in Uganda reveals limited diversity and species-specific gut microbiota. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:4301–4312. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00079-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Malele I, Nyingilili HH, Lyaruu EA, Tauzin M, Ollivier B, Fardeau ML, et al. Bacterial diversity obtained by culturable approaches in the gut of Glossina pallidipes population from a non sleeping sickness focus in Tanzania: preliminary results BMC Microbiol. 2018; 10.1186/s12866-018-1288-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Colman DR, Toolson EC, Takacs-Vesbach CD. Do diet and taxonomy influence insect gut bacterial communities? Mol Ecol. 2012;21:5124–5137. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Poinar GOJ, Wassink HJ. Leegwater-van der Linden ME, van der Geest LP. Serratia marcescens as a pathogen of tsetse flies. Acta Trop. 1979;36:223–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bahia AC, Dong Y, Blumberg BJ, Mlambo G, Tripathi A, BenMarzouk-Hidalgo OJ, et al. Exploring Anopheles gut bacteria for Plasmodium-blocking activity: anti-Plasmodium microbes. Environ Microbiol. 2014;16:2980–2994. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Doudoumis V, Blow F, Saridaki A, Augustinos A, Dyer NA, Goodhead I, et al. Challenging the Wigglesworthia, Sodalis, Wolbachia symbiosis dogma in tsetse flies: Spiroplasma is present in both laboratory and natural populations. Sci Rep. 2017;7:4699. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-04740-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jacob F, Melachio TT, Njitchouang GR, Gimonneau G, Njiokou F, Abate L, et al. Intestinal bacterial communities of trypanosome-infected and uninfected Glossina palpalis palpalis from three human African trypanomiasis foci in Cameroon. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1464. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Herren JK, Paredes JC, Schupfer F, Lemaitre B. Vertical transmission of a Drosophila endosymbiont via cooption of the yolk transport and internalization machinery. mBio. 2013;4:e00532–12-e00532. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00532-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chepkemoi ST, Mararo E, Butungi H, Paredes J, Masiga D, Sinkins SP, et al. Identification of Spiroplasma insolitum symbionts in Anopheles gambiae. Wellcome Open Res. 2017;2:90. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.12468.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Oliver KM, Smith AH, Russell JA. Defensive symbiosis in the real world - advancing ecological studies of heritable, protective bacteria in aphids and beyond. Funct Ecol. 2014;28:341–355. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.12133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jaenike J, Unckless R, Cockburn S, Boelio L, Perlman S. Adaptation via symbiosis: recent spread of a Drosophila defensive symbiont. Science. 2010;329:212–215. doi: 10.1126/science.1188235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shokal U, Yadav S, Atri J, Accetta J, Kenney E, Banks K, et al. Effects of co-occurring Wolbachia and Spiroplasma endosymbionts on the Drosophila immune response against insect pathogenic and non-pathogenic bacteria. BMC Microbiol. 2016;16:16. doi: 10.1186/s12866-016-0634-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ratzka C, Gross R, Feldhaar H. Endosymbiont tolerance and control within insect hosts. Insects. 2012;3:553–572. doi: 10.3390/insects3020553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Telschow A, Flor M, Kobayashi Y, Hammerstein P, Werren JH. Wolbachia-induced unidirectional cytoplasmic incompatibility and speciation: mainland-island model. PLoS One. 2007;2:e701. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brucker RM, Bordenstein SR. The hologenomic basis of speciation: gut bacteria cause hybrid lethality in the genus Nasonia. Science. 2013;341:667–669. doi: 10.1126/science.1240659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brucker RM, Bordenstein SR. Speciation by symbiosis. Trends Ecol Evol. 2012;27:443–451. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Telschow A, Hilgenboecker K, Hammerstein P, Werren JH. Dobzhansky-Muller and Wolbachia-induced incompatibilities in a diploid genetic system. PLoS One. 2014;9:e95488. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Alam U, Medlock J, Brelsfoard C, Pais R, Lohs C, Balmand S, et al. Wolbachia symbiont infections induce strong cytoplasmic incompatibility in the tsetse fly Glossina morsitans. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002415. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schneider DI, Garschall KI, Parker AG, Abd-Alla AMM, Miller WJ. Global Wolbachia prevalence, titer fluctuations and their potential of causing cytoplasmic incompatibilities in tsetse flies and hybrids of Glossina morsitans subgroup species. J Invertebr Pathol. 2013;112:S104–S115. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2012.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schneider DI, Parker AG, AMM A-A, Miller WJ. High-sensitivity detection of cryptic Wolbachia in the African tsetse fly (Glossina spp.). BMC Microbiol. 2018; 10.1186/s12866-018-1291-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 73.Gooding RH. Postmating barriers to gene flow among species and subspecies of tsetse flies (Diptera: Glossinidae) Can J Zool. 1990;68:1727–1734. doi: 10.1139/z90-253. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gooding R. Genetics of sterility among Glossina morsitans sspp and G. swynnertoni hybrids. Zanzibar: United Republic of Tanzania: Backhuys Publishers; 1999. pp. 99–109. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Abd-Alla AM, Marin C, Parker AG, Vreysen MJ. Antiviral drug valacyclovir treatment combined with a clean feeding system enhances the suppression of salivary gland hypertrophy in laboratory colonies of Glossina pallidipes. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:214. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Abd-Alla AM, Kariithi HM, Cousserans F, Parker NJ, Ince IA, Scully ED, et al. Comprehensive annotation of Glossina pallidipes salivary gland hypertrophy virus from Ethiopian tsetse flies: a proteogenomics approach. J Gen Virol. 2016;97:1010–1031. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.000409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Demirbaş-Uzel G, Kariithi HM, Parker AG, Vreysen MJB, Mach RL, Abd-Alla AMM. Susceptibility of tsetse species to Glossina pallidipes salivary gland hypertrophy virus (GpSGHV). Front Microbiol. 2018;9. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 78.Kariithi HM, Boucias DG, Murungi EK, Meki IK, Demirbaş-Uzel G, van Oers MM, et al. Coevolution of hytrosaviruses and host immune responses. BMC Microbiol. 2018; 10.1186/s12866-018-1296-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 79.Kariithi HM, Ince AI, Boeren S, Murungi EK, Meki IK, Otieno EA, et al. Comparative analysis of salivary gland proteomes of two Glossina species that exhibit differential hytrosavirus pathologies. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:89. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Meki IK, Kariithi HM, Ahmadi M, Parker AG, Vreysen MJB, Vlak JM, et al. Hytrosavirus genetic diversity and eco-regional spread in Glossina species. BMC Microbiol. 2018; 10.1186/s12866-018-1297-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 81.Demirbaş-Uzel G, Parker AG, Vreysen MJB, Mach RL, Bouyer J, Takac P, et al. Impact of Glossina pallidipes salivary gland hypertrophy virus (GpSGHV) on a heterologous tsetse fly host, Glossina fuscipes fuscipes. BMC Microbiol. 2018; 10.1186/s12866-018-1276-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 82.Kariithi HM, Meki IK, Boucias DG, Abd-Alla AM. Hytrosaviruses: current status and perspective. Curr Opin Insect Sci. 2017;22:71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cois.2017.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Meki IK, Kariithi HM, Parker AG, Vreysen MJB, Ros VID, Vlak JM, et al. RNA interference-based antiviral immune response against the salivary gland hypertrophy virus in Glossina pallidipes. BMC Microbiol. 2018; 10.1186/s12866-018-1298-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 84.Meki IK, İkbal Aİ, Kariithi HM, Parker AG, MJB V, Vlak JM, et al. Expression profile of G. pallidipes miRNA during infection by the Glossina pallidipes salivary gland hypertrophy virus. Prep. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 85.Zhang G, Hussain M, O’Neill SL, Asgari S. Wolbachia uses a host microRNA to regulate transcripts of a methyltransferase, contributing to dengue virus inhibition in Aedes aegypti. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2013;110:10276–10281. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303603110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Boucias DG, Kariithi HM, Bourtzis K, Schneider DI, Kelley K, Miller WJ, et al. Trans-generational transmission of the Glossina pallidipes hytrosavirus depends on the presence of a functional symbiome. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61150. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Scholte E-J, Knols BG, Samson RA, Takken W. Entomopathogenic fungi for mosquito control: a review. J Insect Sci. 2004;4:19. doi: 10.1093/jis/4.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Maniania NK, Ekesi S, Odulaja A, Okech MA, Nadel DJ. Prospects of a fungus-contamination device for the control of tsetse fly Glossina fuscipes fuscipes. Biocontrol Sci Tech. 2006;16:129–139. doi: 10.1080/09583150500258503. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Maniania NK, Ekesi S. The use of entomopathogenic fungi in the control of tsetse flies. J Invertebr Pathol. 2013;112:S83–S88. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2012.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Maniania NK, Ekesi S, Songa JM. Managing termites in maize with the entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium anisopliae. Insect Sci Its Appl. 2002;22:41–46. [Google Scholar]

- 91.McQuilken MP, Halmer P, Rhodes DJ. Application of microorganisms to seeds. In: Burges HD, editor. Formulation of microbial biopesticides: beneficial microorganisms, nematodes and seed treatments. 1. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publisher; 1998. pp. 255–285. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hajek AE, St. Leger RJ. Interactions between fungal pathogens and insect hosts. Annu Rev Entomol. 1994;39:293–322. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.39.010194.001453. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wamiti LG, Khamis FM, Abd-Alla AMM, Ombura FLO, Akutse KS, Subramanian S, et al. Metarhizium anisopliae infection reduces Trypanosoma congolense reproduction in Glossina fuscipes fuscipes and its ability to acquire or transmit the parasite. BMC Microbiol. 2018; 10.1186/s12866-018-1277-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 94.De Vooght L, Caljon G, De Ridder K, Van Den Abbeele J. Delivery of a functional anti-trypanosome nanobody in different tsetse fly tissues via a bacterial symbiont Sodalis glossinidius. Microb Cell Factories. 2014;13:156. doi: 10.1186/s12934-014-0156-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Demirbaş-Uzel G, Parker AG, De Vooght L, Abbeele JVD, Vreysen MJB, Abd-Alla AMM. Combining paratransgenesis with SIT: impact of ionizing radiation on the DNA copy number of Sodalis glossinidius in tsetse flies. BMC Microbiol. 2018; 10.1186/s12866-018-1283-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 96.de Beer CJ, Moyaba P, Boikanyo SNB, Majatladi D, Yamada H, Venter GJ, et al. Evaluation of radiation sensitivity and mating performance of Glossina brevipalpis males. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0005473. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Everaerts C, Farine J-P, Cobb M, Ferveur J-F. Drosophila cuticular hydrocarbons revisited: mating status alters cuticular profiles. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9607. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Carlson DA, Mramba F, Sutton BD, Bernier UR, Geden CJ. Sex pheromone of the tsetse species, Glossina austeni: isolation and identification of natural hydrocarbons, and bioassay of synthesized compounds. Med Vet Entomol. 2005;19:470–479. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2005.00596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Engl T, Michalkova V, Weiss BL, Demirbaş-Uzel G, Takac P, Miller WJ, et al. Effect of antibiotic treatment and gamma-irradiation on cuticular hydrocarbon profiles and mate choice in tsetse flies (Glossina M. morsitans). BMC Microbiol. 2018; 10.1186/s12866-018-1292-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 100.Coutinho-Abreu IV, Zhu KY, Ramalho-Ortigao M. Transgenesis and paratransgenesis to control insect-borne diseases: current status and future challenges. Parasitol Int. 2010;59:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wilke ABB, Marrelli MT. Paratransgenesis: a promising new strategy for mosquito vector control. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:342. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-0959-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Durvasula RV, Gumbs A, Panackal A, Kruglov O, Aksoy S, Merrifield RB, et al. Prevention of insect-borne disease: an approach using transgenic symbiotic bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1997;94:3274–3278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wang S, Ghosh AK, Bongio N, Stebbings KA, Lampe DJ, Jacobs-Lorena M. Fighting malaria with engineered symbiotic bacteria from vector mosquitoes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109:12734–12739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204158109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bongio NJ, Lampe DJ. Inhibition of Plasmodium berghei development in mosquitoes by effector proteins secreted from Asaia sp bacteria using a novel native secretion signal. PLOS ONE. 2015;10:e0143541. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Medlock J, Atkins KE, Thomas DN, Aksoy S, Galvani AP. Evaluating paratransgenesis as a potential control strategy for African trypanosomiasis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2374. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.De Vooght L, Caljon G, Stijlemans B, De Baetselier P, Coosemans M, Van Den Abbeele J. Expression and extracellular release of a functional anti-trypanosome Nanobody® in Sodalis glossinidius, a bacterial symbiont of the tsetse fly. Microb Cell Factories. 2012;11:23. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-11-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Shaida SS, Weber JS, Gbem TT, Ngomtcho CSH, Musa UB, Achukwi MD, et al. Diversity and phylogenetic relationships of Glossina populations in Nigeria. BMC Microbiol. 2018; 10.1186/s12866-018-1293-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 108.De Vooght L, Caljon G, Van Hees J, Van Den Abbeele J. Paternal transmission of a secondary symbiont during mating in the viviparous tsetse fly. Mol Biol Evol. 2015;32:1977–1980. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msv077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.De Vooght L, Van Keer S, Van Den Abbeele J. Towards improving tsetse fly paratransgenesis: stable colonization of Glossina morsitans morsitans with genetically modified Sodalis. BMC Microbiol. 2018; 10.1186/s12866-018-1282-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 110.Isaac C, Ciosi M, Hamilton A, Scullion KM, Dede P, Igbinosa IB, et al. Molecular identification of different trypanosome species and subspecies in tsetse flies of northern Nigeria. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:301. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1585-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Abbeele JVD, Rotureau B. New insights in the interactions between African trypanosomes and tsetse flies. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2013;3:63. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2013.00063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.International Glossina Genome Initiative. Attardo GM, Abila PP, Auma JE, Baumann AA, Benoit JB, et al. Genome sequence of the tsetse fly (Glossina morsitans): vector of African trypanosomiasis. Science. 2014;344:380–386. doi: 10.1126/science.1249656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Adam Y, Bouyer J, Dayo G-K, Mahama CI, Vreysen MJB, Cecchi G, et al. Genetic comparison of Glossina tachinoides populations in three river basins of the upper west region of Ghana and implications for tsetse control. Infect Genet Evol. 2014;28:588–595. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2014.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Aksoy S, Attardo G, Berriman M, Christoffels A, Lehane M, Masiga D, et al. Human African trypanosomiasis research gets a boost: unraveling the tsetse genome. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e2624. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Aksoy S, Buscher P, Lehane M, Solano P, Van Den Abbeele J. Human African trypanosomiasis control: achievements and challenges. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0005454. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Aksoy S, Weiss BL, Attardo GM. Trypanosome transmission dynamics in tsetse. Curr Opin Insect Sci. 2014;3:43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.cois.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Alves-e-Silva TL, Savage AF, Aksoy S. Transcript abundance of putative lipid phosphate phosphatases during development of Trypanosoma brucei in the tsetse fly. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016;94:890–893. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Awuoche EO, Weiss BL, Vigneron A, Mireji PO, Aksoy E, Nyambega B, et al. Molecular characterization of tsetse’s proboscis and its response to Trypanosoma congolense infection. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0006057. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Benoit JB, Attardo GM, Baumann AA, Michalkova V, Aksoy S. Adenotrophic viviparity in tsetse flies: potential for population control and as an insect model for lactation. Annu Rev Entomol. 2015;60:351–371. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-010814-020834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Benoit JB, Attardo GM, Michalkova V, Krause TB, Bohova J, Zhang Q, et al. A novel highly divergent protein family identified from a viviparous insect by RNA-seq analysis: a potential target for tsetse fly-specific abortifacients. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1003874. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Benoit JB, Hansen IA, Attardo GM, Michalková V, Mireji PO, Bargul JL, et al. Aquaporins are critical for provision of water during lactation and intrauterine progeny hydration to maintain tsetse fly reproductive success. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e2517. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Beschin A, Van Den Abbeele J, De Baetselier P, Pays E. African trypanosome control in the insect vector and mammalian host. Trends Parasitol. 2014;30:538–547. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Ciosi M, Masiga DK, Turner CMR. Laboratory colonisation and genetic bottlenecks in the tsetse fly Glossina pallidipes. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e2697. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Geiger A, Bossard G, Sereno D, Pissarra J, Lemesre J-L, Vincendeau P, et al. Escaping deleterious immune response in their hosts: lessons from trypanosomatids. Front Immunol. 2016;7:212. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Geiger A, Hamidou Soumana I, Tchicaya B, Rofidal V, Decourcelle M, Santoni V, et al. Differential expression of midgut proteins in Trypanosoma brucei gambiense-stimulated vs non-stimulated Glossina palpalis gambiensis flies. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:444. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Gitonga PK, Ndung’u K, Murilla GA, Thande PC, Wamwiri FN, Auma JE, et al. Differential virulence and tsetse fly transmissibility of Trypanosoma congolense and Trypanosoma brucei strains. Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 2017;84:e1–10. doi: 10.4102/ojvr.v84i1.1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Gloria-Soria A, Dunn WA, Telleria EL, Evans BR, Okedi L, Echodu R, et al. Patterns of genome-wide variation in Glossina fuscipes fuscipes tsetse flies from Uganda. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2016;6:1573–1584. doi: 10.1534/g3.116.027235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Hamidou Soumana I, Klopp C, Ravel S, Nabihoudine I, Tchicaya B, Parrinello H, et al. RNA-seq de novo assembly reveals differential gene expression in Glossina palpalis gambiensis infected with Trypanosoma brucei gambiense vs non-infected and self-cured flies. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:1259. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Hamidou Soumana I, Tchicaya B, Chuchana P, Geiger A. Midgut expression of immune-related genes in Glossina palpalis gambiensis challenged with Trypanosoma brucei gambiense. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:609. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Horáková E, Changmai P, Vancová M, Sobotka R, Van Den Abbeele J, Vanhollebeke B, et al. The Trypanosoma brucei TbHrg protein is a heme transporter involved in the regulation of stage-specific morphological transitions. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:6998–7010. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.762997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Hyseni C, Kato AB, Okedi LM, Masembe C, Ouma JO, Aksoy S, et al. The population structure of Glossina fuscipes fuscipes in the Lake Victoria basin in Uganda: implications for vector control. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:222. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Kamidi CM, Saarman NP, Dion K, Mireji PO, Ouma C, Murilla G, et al. Multiple evolutionary origins of Trypanosoma evansi in Kenya. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0005895. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Manangwa O, Nkwengulila G, Ouma JO, Mramba F, Malele I, Dion K, et al. Genetic diversity of Glossina fuscipes fuscipes along the shores of Lake Victoria in Tanzania and Kenya: implications for management. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:268. doi: 10.1186/s13071-017-2201-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Manangwa O, Ouma J, Malele I, Msangi A, Mramba F, Nkwengulila G. Distribution and population size of Glossina fuscipes fuscipes (tsetse flies) along the Lake Victoria, for trypanosomiasis management in Tanzania. Livest Res Rural Dev. 2015;27:31. [Google Scholar]

- 135.Matetovici I, Caljon G, Van Den Abbeele J. Tsetse fly tolerance to T brucei infection: transcriptome analysis of trypanosome-associated changes in the tsetse fly salivary gland. BMC Genomics. 2016;17:971. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-3283-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Mwangi S, Attardo G, Suzuki Y, Aksoy S, Christoffels A. TSS seq based core promoter architecture in blood feeding tsetse fly (Glossina morsitans morsitans) vector of trypanosomiasis. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:722. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1921-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Okeyo WA, Saarman NP, Mengual M, Dion K, Bateta R, Mireji PO, et al. Temporal genetic differentiation in Glossina pallidipes tsetse fly populations in Kenya. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:471. doi: 10.1186/s13071-017-2415-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Opiro R, Saarman NP, Echodu R, Opiyo EA, Dion K, Halyard A, et al. Evidence of temporal stability in allelic and mitochondrial haplotype diversity in populations of Glossina fuscipes fuscipes (Diptera: Glossinidae) in northern Uganda. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:258. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1522-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Opiro R, Saarman NP, Echodu R, Opiyo EA, Dion K, Halyard A, et al. Genetic diversity and population structure of the tsetse fly Glossina fuscipes fuscipes (Diptera: Glossinidae) in northern Uganda: implications for vector control. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0005485. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Savage AF, Kolev NG, Franklin JB, Vigneron A, Aksoy S, Tschudi C. Transcriptome profiling of Trypanosoma brucei development in the tsetse fly vector Glossina morsitans. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0168877. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0168877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]