Abstract

Background

Snake venom phospholipases A2 (PLA2s) have been reported to induce myotoxic, neurotoxic, hemolytic, edematogenic, cytotoxic and proinflammatory effects. This work aimed at the isolation and functional characterization of a PLA2 isolated from Bothrops jararaca venom, named BJ-PLA2-I.

Methods and Results

For its purification, three consecutive chromatographic steps were used (Sephacryl S-200, Source 15Q and Mono Q 5/50 GL). BJ-PLA2-I showed acidic characteristics, with pI~ 4.4 and molecular mass of 14.2 kDa. Sequencing resulted in 60 amino acid residues that showed high similarity to other Bothrops PLA2s, including 100% identity with BJ-PLA2, an Asp49 PLA2 previously isolated from B. jararaca venom. Being an Asp49 PLA2, BJ-PLA2-I showed high catalytic activity, and also inhibitory effects on the ADP-induced platelet aggregation. Its inflammatory characterization showed that BJ-PLA2-I was able to promote leukocyte migration in mice at different concentrations (5, 10 and 20 μg/mL) and also at different response periods (2, 4 and 24 h), mainly by stimulating neutrophil infiltration. Furthermore, increased levels of total proteins, IL-6, IL-1β and PGE2 were observed in the inflammatory exudate induced by BJ-PLA2-I, while nitric oxide, TNF-α, IL-10 and LTB4 levels were not significantly altered. This toxin was also evaluated for its cytotoxic potential on normal (PBMC) and tumor cell lines (HL-60 and HepG2). Overall, BJ-PLA2-I (2.5–160 μg/mL) promoted low cytotoxicity, with cell viabilities mostly varying between 70 and 80% and significant values obtained for HL-60 and PBMC only at the highest concentrations of the toxin evaluated.

Conclusions

BJ-PLA2-I was characterized as an acidic Asp49 PLA2 that induces acute local inflammation and low cytotoxicity. These results should contribute to elucidate the action mechanisms of snake venom PLA2s.

Keywords: Snake venom, Bothrops jararaca, Phospholipase A2, Inflammation, Cytotoxicity

Background

Phospholipases are lipolytic enzymes classified as A1, A2, B, C or D, according to the position where they induce lipid hydrolysis [1]. Phospholipases A2 (PLA2s) catalyze the hydrolysis of fatty acids at the sn-2 position of the phospholipid membranes, and release lysophospholipids and free fatty acids, especially polyunsaturated ones, such as arachidonic acid. Based on their structure, catalytic mechanisms, localization and evolutionary interactions, the PLA2s can be divided into 6 major families and 15 subgroups, with snake venom PLA2s being classified as secreted PLA2s (sPLA2) from groups I (Elapidae and Hydrophiidae snakes) or II (Viperidae and Crotalidae snakes) [2, 3].

In general, snake venom PLA2s are acidic or basic enzymes with molecular masses ranging from 13 to 15 kDa, and structure consisting of about 120 amino acid residues stabilized by 7 disulfide bonds, making them very stable molecules. They present a highly conserved catalytic site formed by the amino acid residues His48, Asp49, Tyr52 and Asp99. Aspartic acid residue at position 49 coordinates the hydrolysis reaction of phospholipids together with the residues of the Ca2+ binding loop, with this ion being an essential cofactor in the catalytic activity of PLA2s. Also commonly reported in the literature is the existence of PLA2 homologues with a mutation at position 49 that exchanges the aspartic acid residue for a lysine. These toxins are called Lys49 PLA2-like molecules, and this amino acid substitution leads to partial or total loss of their catalytic activity [4, 5]. Thus, Asp49 PLA2s present high catalytic activity, while Lys49 PLA2-like molecules do not, but can still induce several biological effects, such as myonecrosis, inflammation and cytotoxicity [4, 6–8].

PLA2s are usually among the most abundant components of snake venoms, being responsible for various toxic and pharmacological effects, by mechanisms not yet fully understood [9]. During envenomations, they assist in the prey digestion, and have also been described to induce myotoxic, neurotoxic, cytotoxic, hemolytic, edematogenic, hypotensive, anticoagulant, platelet aggregation inhibition/activation, bactericidal and proinflammatory effects [10].

Considering that snake venom PLA2s can act directly on phospholipid membranes, they should be able to promote alterations in lipid biosynthesis and dysregulation of lipogenesis that could have great impact on the metabolism of tumor cells and also on the formation of lipid mediators derived from arachidonic acid, which perform essential roles in inflammation. Hence, such PLA2s might serve as useful tools to elucidate the mechanisms involved in cancer/inflammation and as possible molecular models for new antitumor/anti-inflammatory drugs [11–14]. In fact, different PLA2s have been studied for their proinflammatory, antitumor and antiangiogenic properties, among them acidic and basic PLA2s, as well as synthetic peptides derived from Lys49 PLA2 homologues [11, 15].

Therefore, research on PLA2s has attained paramount importance, not only to better understand the role of these toxins in envenomations, but also to discover molecular and biotechnological tools for the formulation of new drugs to combat inflammatory diseases and cancer. Thus, this study aims to evaluate the cytotoxic and inflammatory effects of an acidic phospholipase A2 isolated from Bothrops jararaca snake venom.

Methods

Venom and other materials

Bothrops jararaca venom was extracted and processed in the Laboratory of Herpetology of the Butantan Institute (São Paulo, Brazil), which then kindly donated it for the development of the present study. The chromatographic resins and reagents for the biochemical and enzymatic assays were obtained from GE Healthcare, Merck, Thermo Scientific or Sigma-Aldrich. Other materials and equipment used were described throughout the methodology. Unless otherwise specified, reagents were of analytical grade.

Animals

Male BALB/c mice (20–25 g, 6–8 weeks old) used in the inflammatory experiments were bred and provided by the animal facilities of the University of São Paulo, campus of Ribeirão Preto (São Paulo, Brazil).

Human blood

The human plasma used in the platelet aggregation experiments and the peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) for cytotoxicity assays were obtained from blood donated by healthy volunteers aged 20–40 years, from both sexes, and who had not been using any medication for 10 days prior to the collection.

Toxin isolation

To isolate the PLA2 from B. jararaca venom, we used three consecutive chromatographic steps: (i) Sephacryl S-200 molecular exclusion chromatography, (ii) Source 15Q anion exchange chromatography and (iii) Mono Q 5/50 GL anion exchange chromatography.

Firstly, B. jararaca crude venom (200 mg) was suspended in 2 mL of 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate buffer (Ambic) pH 8.0, followed by centrifugation at 10,000×g for 10 min at room temperature. Next, the supernatant was applied to a Sephacryl S-200 column (127 × 3.5 cm), previously equilibrated and eluted with the same buffer at room temperature, collecting fractions of 3 mL/tube at a flow rate of 15 mL/h. All fractions were monitored in a Beckman DU® 640 spectrophotometer, using a wavelength of 280 nm, and pools were separated based on the chromatographic profile. SDS-PAGE and phospholipase activity were employed to define the pool of interest (identified as fraction F), which was then submitted to the next chromatographic step.

For the second step, the lyophilized fraction F (~ 50 mg) was suspended in 1 mL of 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8.0, and centrifuged at 10,000×g for 10 min. The clear supernatant was applied to a Source 15Q column (11.5 × 2.6 cm), previously equilibrated at room temperature with 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8.0. Fractions were eluted using an AKTA FPLC system (GE Healthcare) and a linear gradient of NaCl (from 0 to 1 M), collecting fractions of 3 mL/tube at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. Absorbance was monitored at 280 nm and, once again, SDS-PAGE and phospholipase activity were utilized to determine the pool of interest (identified as fraction S.10).

For the third chromatographic step, the lyophilized fraction S.10 (~ 1.2 mg) was suspended in 550 μL of 50 mM Ambic buffer, pH 8.0, and centrifuged at 10,000×g for 10 min. The supernatant was then applied to a Mono Q 5/50 GL column (5 × 0.5 cm), previously equilibrated at room temperature with 50 mM Ambic buffer, pH 8.0. Fractions were eluted using an AKTA FPLC system (GE Healthcare) and a linear gradient of NaCl (from 0 to 1 M), collected at 0.5 mL/tube at a flow rate of 1 mL/min, and monitored for absorbance at 280 nm.

The major peak from the latter chromatographic step was denominated BJ-PLA2-I and was then evaluated for its purity by reversed-phase chromatography. For that, lyophilized BJ-PLA2-I (~ 200 μg) was dissolved in solution A (0.1% trifluoroacetic acid - TFA) and centrifuged at 10,000×g for 10 min; next the resulting supernatant was applied to a CLC-ODS C18 reversed-phase column (25 × 0.46 cm) using a HPLC system (Shimadzu Biotech). The elution was performed at a flow rate of 1 mL/min with a linear concentration gradient of solutions A and B (70% acetonitrile and 0.1% TFA), as follows: 100% solution A (15 min), 0–100% solution B (50 min), 100% solution B (10 min). Absorbance of fractions was monitored at 280 nm.

Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in the presence of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS-PAGE)

SDS-PAGE of chromatographic fractions and the purified toxin was performed according to Laemmli [16], using 12% polyacrylamide gels and reducing or non-reducing conditions (presence or absence of β-mercaptoethanol, respectively). The molecular mass standard used was from Thermo Scientific (ref #26610) and ranged from 14.4 to 116 kDa.

Protein quantification

Protein was quantified using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific, ref. #23225), following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Molecular mass determination

Molecular mass analyses were performed using an AXIMA Performance MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometer (Shimadzu Biotech), acquiring mass spectra ranging from 3000 to 80,000 m/z in positive linear mode.

Isoelectric focusing

Isoelectric focusing separations were performed as described by Arantes et al. [17], using a 7% polyacrylamide gel containing carrier ampholytes with pH ranging from 3 to 10 (Pharmalyte, Sigma-Aldrich).

Circular dichroism spectrometry

Spectra were obtained at wavelengths between 180 and 260 nm with a JASCO J-815 circular dichroism (CD) spectrophotometer using a nitrogen flush in 1 mm path length quartz cuvettes at room temperature. To investigate the conformational changes, spectra were recorded in 0.01 M Tris-HCl pH 7.5 at a protein concentration of 0.5 mg/mL. CD spectra were typically recorded as an average of 10 scans, which were obtained in millidegrees.

Amino acid sequence determination

The partial amino acid sequence of BJ-PLA2-I was determined by a combination of Edman degradation and MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry techniques. N-terminal sequencing was performed in an automatic protein sequencer (PPSQ-33A system, Shimadzu Biotech), using ~ 200 pmol of the toxin. For the mass spectrometry sequencing, the toxin was first subjected to enzymatic digestion with trypsin (Promega Corp.) for 24 h at 37 °C. After that period, tryptic peptides from the reaction were purified on ZipTip columns (POROS R2, Perseptive Biosystems) and then resuspended in a matrix containing α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (10 mg/ml); analyses were performed in a MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometer (4800-Plus, Applied Biosystems).

The results generated were compared to sequences deposited in the NCBI and Swiss-Prot databases using the sites BLAST (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and MASCOT (http://www.matrixscience.com/search_form_select.html). The partial sequence of BJ-PLA2-I was then aligned to sequences of other PLA2s deposited in the NCBI database using the program ClustalX v.2.0.11 (http://www.clustal.org/).

Molecular modeling

The crystallographic model of BthA-I-PLA2 from Bothrops jararacussu venom (PDB id: 1ZLB) [18] was chosen as the best model for the construction of the theoretical structural model of BJ-PLA2-I (100% probability, E-value: 1.3 e− 37, according to HHpred), using the MODELLER program (https://toolkit.tuebingen.mpg.de/#/tools/modeller) [19, 20]. The analyses of the obtained models were carried out by three different methodologies, using the programs PROCHECK (https://swissmodel.expasy.org/), VERIFY 3D (http://servicesn.mbi.ucla.edu/Verify3D/) and WHAT IF (http://swift.cmbi.ru.nl/servers/html/index.html). All figures resulting from these studies were constructed by the program PYMOL v1.7.4.4.

Phospholipase activity

The phospholipase activity of the chromatographic fractions and BJ-PLA2-I was evaluated on egg yolk-agar plates, following the methodology described by Gutiérrez et al. [21], with modifications by Menaldo et al. [22]. Assessed samples included a negative control of phosphate buffered saline (PBS), a positive control of B. jararaca venom (15 μg) and different quantities of BJ-PLA2-I (0.08–2.5 μg), all diluted in PBS. After an overnight incubation of the samples on plates at 37 °C, the phospholipase activity was expressed as the size (in cm) of translucent halos formed by each sample.

Effects on platelets

Platelet aggregation inhibitory assays were based on the turbidimetric method of Born [23], using platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and adenosine diphosphate (ADP) as agonist. PRP was obtained from blood collected by venipuncture using 3.8% sodium citrate (9:1, v/v) as anticoagulant and then centrifuged at 200×g and room temperature for 10 min. After collecting the PRP, the same blood tubes were centrifuged again, this time at 2000×g for 15 min, to obtain platelet-poor plasma (PPP). Plasma platelet counts were performed in a Neubauer chamber, obtaining an approximate value of 2.5 × 105 platelets/mL.

The assays were performed using a platelet aggregometer (Chrono-log Corporation, model 490 2D) and the software AggroLink. Initially, PRP was incubated at 37 °C for 5 min, and then 5 μM ADP was added to determine the percentage of platelet aggregation. Next, PRP was incubated at 37 °C for 5 min, and then for another 5 min with BJ-PLA2-I (20.5 μg/mL). After this period, 5 μM ADP was added to the tube to induce platelet aggregation, and the reaction was assayed for additional 10 min. Results were expressed as percentages of platelet aggregation.

Inflammatory effects

Leukocyte recruitment

This evaluation was performed essentially as described by Menaldo et al. [24]. Initially, BALB/c mice (5 animals/group) were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with sterile PBS (negative control) or different concentrations of BJ-PLA2-I (5, 10 and 20 μg/mL) and animals were euthanized after 4 h by instillation of CO2. Then, their peritoneal cavities were washed with cold PBS, and exudates were used to perform the total and differential leukocyte counts.

Subsequently, the same protocol was repeated using a single concentration of BJ-PLA2-I (10 μg/mL, equivalent to a dose of 0.12 mg/kg) and different stimulation periods (2, 4 and 24 h). After counting, peritoneal exudates were centrifuged at 400×g for 10 min at 10 °C and the cell-free supernatants were used for the quantification of total proteins, soluble mediators and nitric oxide (NO).

Quantification of total proteins

The total protein levels in the peritoneal supernatants from mice injected with BJ-PLA2-I or PBS were quantified using Bradford reagent (Sigma-Aldrich), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Quantification of mediators

The concentrations of cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β and IL-10) and eicosanoids (PGE2 and LTB4) in the cell-free peritoneal fluid from mice injected with BJ-PLA2-I or PBS were quantified by ELISA kits, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (R&D Systems or Cayman Chemical).

Quantification of nitric oxide

NO production was determined by the quantification of nitrite (NO2−) in the peritoneal exudates of mice using a colorimetric assay based on the Griess reaction [25].

Cytotoxic effects

Cell cultures

Human normal or tumor cells were used in the cytotoxicity experiments, i.e. PBMC (peripheral blood mononuclear cells), HL-60 (human promyelocytic leukemia) and HepG2 (human liver carcinoma). PBMC was obtained from human blood collected in heparin tubes (BD vacutainer ref. #367874) and separated by Histopaque-1077 (Sigma-Aldrich ref. #10771), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The tumor cell lines HL-60 (CCL-240) and HepG2 (HB-8065) were obtained from ATCC (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD, USA). Before treatments, PBMC and HL-60 cells were cultured for 24 h at 37 °C in RPMI-1640 medium, while HepG2 was cultured in DMEM (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium), according to Costa et al. [26].

Cytotoxicity assays

Cell viability was assessed by the MTT method [27]. PBMC, HL-60 and HepG2 cells were treated with different concentrations of BJ-PLA2-I (2.5–160 μg/mL) for 24 h at 37 °C in a CO2 incubator. MTT solution was added to the cultures (500 μg/mL, final concentration) 3 h before the end of treatments, and the reaction was stopped by the addition of DMSO (100 μL) to the cell cultures. Cells treated only with sterile PBS were used as negative controls whereas cells treated with cisplatin (Incel, Darrow®) at 250 μg/mL (final concentration) as positive controls. Results were expressed as percentage of cell viability in comparison to the negative controls.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of the results was performed by the software GraphPad Prism 5, using the Student’s t test or one-way ANOVA method with Tukey’s post-test, comparing all treatments to the negative controls and considering values of p < 0.05 as significant.

Results

Isolation of BJ-PLA2-I

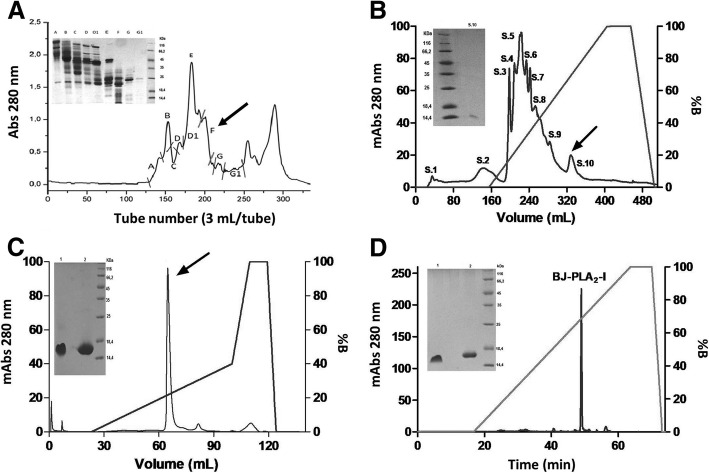

B. jararaca venom fractionation was initiated with a molecular exclusion chromatography on Sephacryl S-200, which resulted in several protein fractions that were named A to G1 (Fig. 1a). Fraction F was selected for the next chromatographic step considering its positive phospholipase activity and its protein profile on SDS-PAGE. The following chromatography on a Source 15Q anion exchange column resulted in fractions denominated S.1 to S.10 (Fig. 1b), with fraction S.10 being chosen according to the above mentioned parameters. After the third chromatographic step on a Mono Q anion exchange column (Fig. 1c), the toxin of interest, named BJ-PLA2-I, was identified as the major fraction that showed molecular mass around 14 kDa and phospholipase activity. Thus, BJ-PLA2-I was successfully isolated from B. jararaca venom after these three chromatographic steps, with high purity levels shown by reversed-phase HPLC (Fig. 1d), but very low recovery (~ 0.2%) (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Isolation of BJ-PLA2-I from B. jararaca venom. a Chromatographic profile of Bothrops jararaca venom (200 mg) on Sephacryl S-200 column: Elution was carried out with 50 mM Ambic, pH 8.0. Inset, 12% SDS-PAGE of the fractions from A to G1 in non-reducing conditions. b Chromatographic profile of fraction F (~ 50 mg) on a Source 15Q column: Elution was carried out with 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, and a linear concentration gradient of NaCl (from 0 to 1 M). Inset, 12% SDS-PAGE of the fraction of interest (arrow) in non-reducing conditions. c Chromatographic profile of fraction S.10 (~ 1.2 mg) on a Mono Q 5/50 GL column: Elution was carried out with 50 mM Ambic, pH 8.0, and a linear concentration gradient of NaCl (from 0 to 1 M). Inset, 12% SDS-PAGE of the fraction of interest (arrow) in non-reducing (1) and reducing (2) conditions. d Chromatographic profile of BJ-PLA2-I (~ 200 μg) on a C18 reversed-phase column using a HPLC system: The column was previously equilibrated with solution A (0.1% TFA), and elution was performed at flow rate of 1 mL/min with a linear concentration gradient of solution B (70% acetonitrile and 0.1% TFA). Inset, 12% SDS-PAGE of BJ-PLA2-I in non-reducing (1) or reducing (2) conditions

Table 1.

Recovery rates of BJ-PLA2-I purification process

| Total protein (mg)a | Recovery (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| B. jararaca venom | 144.2 | 100 |

| Fraction F (Sephacryl S-200) | 15.2 | 10.5 |

| Fraction S.10 (Source 15Q) | 1.2 | 0.8 |

| BJ-PLA2-I (Mono Q 5/50 GL) | 0.28 | 0.2 |

aProtein concentration determined by the BCA method

Biochemical, functional and structural characterization

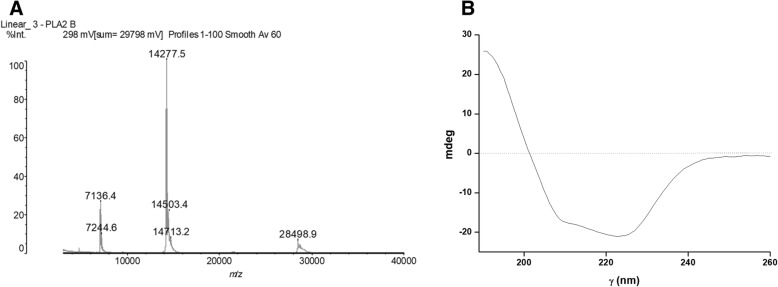

Once BJ-PLA2-I was purified, we performed different assays in order to characterize the toxin. Its molecular mass determined by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry was of 14,276 Da (Fig. 2a), while its pI was approximately 4.4 as determined by isoelectric focusing (data not shown), thus showing an acidic character.

Fig. 2.

a Molecular mass of BJ-PLA2-I determined by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (MM~ 14.2 kDa). b Circular dichroism spectrum of BJ-PLA2-I

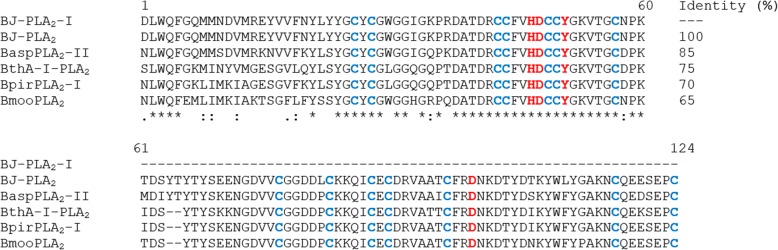

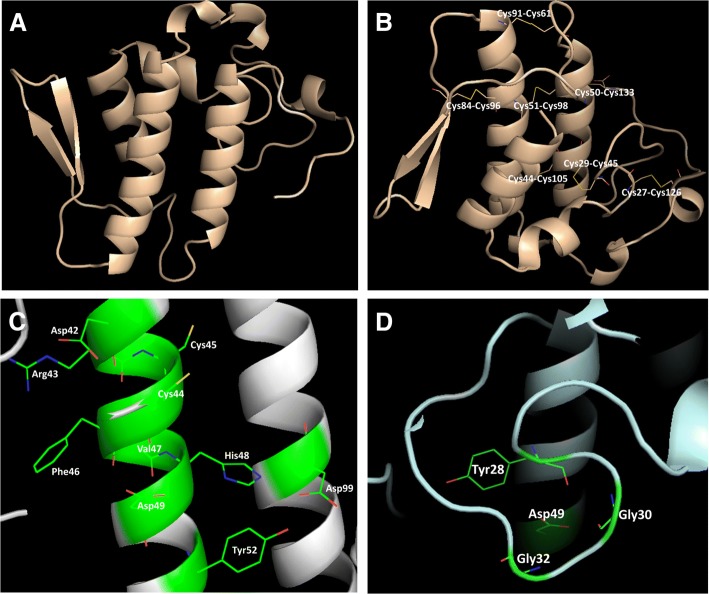

The secondary structure content of the PLA2 was analyzed by CD spectroscopy, showing characteristic curves of helical proteins with well-defined peaks at 208 and 222 nm (Fig. 2b). Its partial amino acid sequence was achieved combining Edman degradation and MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry techniques, resulting in 60 amino acid residues from its N-terminal, including 7 cysteine residues and 3 residues belonging to its catalytic site (His48, Asp49 and Tyr52) (Fig. 3). When this sequence was aligned with sequences from other Bothrops PLA2s, the identity varied from 65 to up to 100% (Fig. 3). Molecular modeling of BJ-PLA2-I (Fig. 4a) was made based on the crystal structure of the acidic BthA-I-PLA2 from B. jararacussu venom, and was useful for illustrating the seven intrachain disulfide bridges formed (Cys27- Cys126, Cys29-Cys45, Cys44-Cys105, Cys50-Cys133, Cys51-Cys98, Cys61-Cys91, and Cys84-Cys96) (Fig. 4b), the conserved catalytic site (D42XCCXXHD49; Tyr52; Asp99) (Fig. 4c) and the amino acid side chains essential for the Ca2+ binding (Tyr28; Gly30; Gly32; Asp49) (Fig. 4d).

Fig. 3.

Multiple alignment of the partial amino acid sequence of BJ-PLA2-I with sequences of other phospholipases A2 from Bothrops venoms. Cysteine residues responsible for the formation of disulfide bonds are highlighted in blue and amino acid residues belonging to the catalytic site are in red. The toxins selected for alignment were: BJ-PLA2 from B. jararaca (gi: 3914258) [28], BaspPLA2-II from B. asper (gi: 292630844) [58], BthA-I-PLA2 from B. jararacussu (gi: 82211983) [18], BpirPLA2-I from B. pirajai (gi: 357580469) [32] and BmooPLA2 from B. moojeni (gi: 403399514) [33]. (*) indicates positions with fully conserved amino acid residues; (:) indicates conservation of amino acid groups with high score; (.) indicates conservation of amino acid groups with a lower score

Fig. 4.

Molecular modeling of BJ-PLA2-I. The theoretical structural model of BJ-PLA2-I (a) was generated by the program MODELLER, using the crystal structure of BthA-I-PLA2 from B. jararacussu venom (PDB id: 1ZLB) [18] as model. Highlighted are the seven intrachain disulfide bridges formed (b), the amino acid residues from the conserved catalytic site (c) and the Ca2+ binding loop (d)

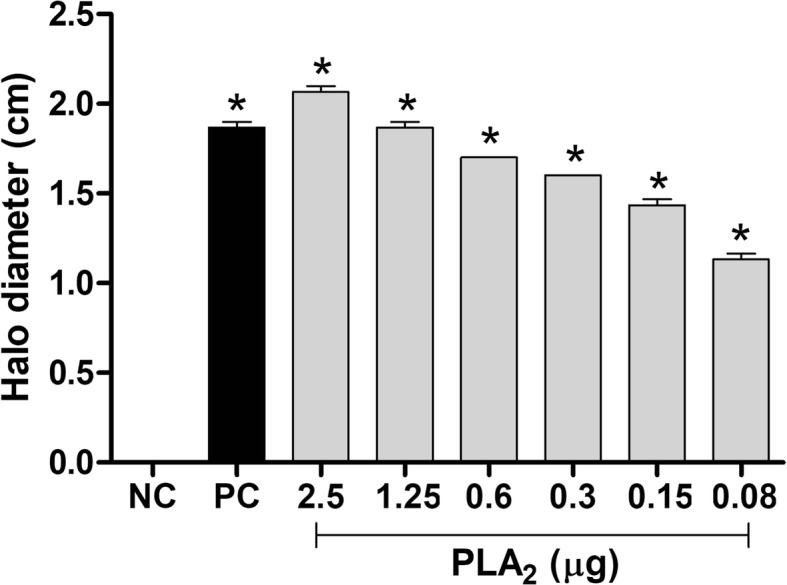

BJ-PLA2-I high enzymatic activity was shown by its high phospholipase activity, with 2.5 μg inducing an effect higher than that of 15 μg of B. jararaca venom (Fig. 5). In addition, our results showed that BJ-PLA2-I was able to inhibit the ADP-induced platelet aggregation by about 50% (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

Phospholipase activity of BJ-PLA2-I. The assay was evaluated on egg yolk-agar plates incubated overnight at 37 °C with PBS (NC = negative control), B. jararaca venom (15 μg) (PC = positive control) or BJ-PLA2-I (0.08–2.5 μg). The phospholipase activity is relative to the size (in cm) of translucent halos formed by each sample. Results were expressed as means ± SD (n = 2) of two independent experiments. *p < 0.05 compared to the negative control (NC)

Fig. 6.

Inhibition of platelet aggregation by BJ-PLA2-I. Initially, platelet-rich plasma (PRP) was incubated at 37 °C with ADP (5 μM) for 10 min to determine the percentage of platelet aggregation. Next, PRP was first incubated at 37 °C with BJ-PLA2-I (20.5 μg/mL) for 5 min, followed by addition of ADP (5 μM) and evaluation for another 10 min to determine the inhibition promoted by the toxin. Results were expressed as mean percentages ± SD (n = 2) of two independent experiments. *p < 0.05 compared to the ADP group

Evaluation of inflammatory effects

The inflammatory effects of different concentrations of BJ-PLA2-I were initially evaluated by the influx of leukocytes into the peritoneal cavity of mice at 4 h after injection (Fig. 7). The toxin at 10 and 20 μg/mL increased the total number of leukocytes (Fig. 7a), while the number of neutrophils was increased at all concentrations evaluated (Fig. 7b) and the number of mononuclear cells did not change significantly in comparison to the PBS control (Fig. 7c).

Fig. 7.

Leukocyte recruitment induced by different concentrations of BJ-PLA2-I in mice. Migration of total leukocytes (a), neutrophils (b) and mononuclear cells (c) was evaluated at 4 h after the injection of BJ-PLA2-I (5, 10 or 20 μg/mL) in the peritoneal cavity of mice. Control groups were injected only with PBS. Results were expressed as means ± SD (n = 5) of two independent experiments. *p < 0.05 compared to the control group (PBS)

Afterward, a single concentration of BJ-PLA2-I (10 μg/mL) was employed to evaluate the leukocyte migration response at different periods (2, 4 and 24 h) after toxin injection (Fig. 8). Our results showed that this PLA2 induced increased leukocyte recruitment after all three stimulation periods evaluated (Fig. 8a), with significant increases of neutrophils at 2 and 4 h (Fig. 8b) and of mononuclear cells at 24 h (Fig. 8c).

Fig. 8.

Leukocyte recruitment induced by BJ-PLA2-I in mice after different stimulation periods. Migrations of total leukocytes (a), neutrophils (b) and mononuclear cells (c) were evaluated at 2, 4 and 24 h after the injection of BJ-PLA2-I (10 μg/mL) in the peritoneal cavity of mice. Control groups were injected only with PBS. Results were expressed as means ± SD (n = 5) of two independent experiments. *p < 0.05 compared to the control group (PBS)

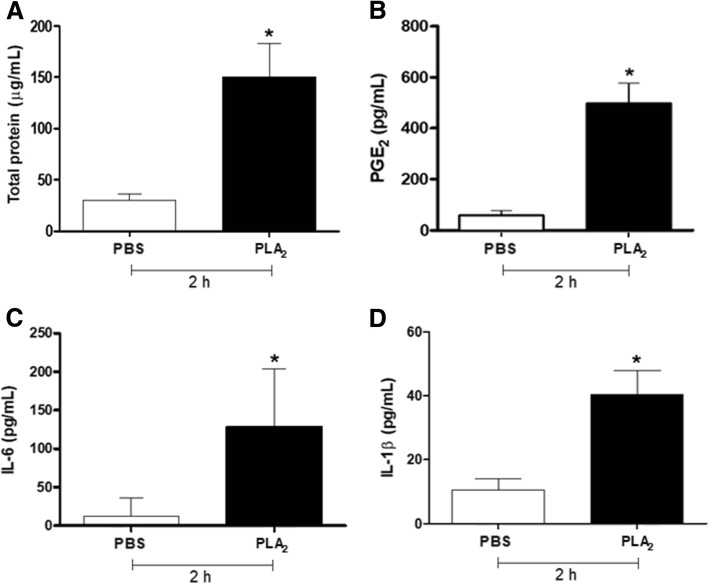

Considering these results, we then investigated the protein extravasation and the production of inflammatory mediators induced by BJ-PLA2-I at 10 μg/mL after 2, 4 and 24 h. Compared to the PBS control, mice stimulated with BJ-PLA2-I did not show significant changes in the levels of mediators such as LTB4, TNF-α, IL-10 and NO (data not shown), but they did present increased levels of total proteins, PGE2, IL-6 and IL-1β only at 2 h after injection (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Increased levels of total proteins and inflammatory mediators induced by BJ-PLA2-I in mice. The cell-free supernatants from the peritoneal exudate of mice stimulated for 2 h with BJ-PLA2-I (10 μg/mL) were used for the quantification of total proteins (a), PGE2 (b), IL-6 (c) and IL-1β (d). Results were expressed as means ± SD (n = 5) of two independent experiments. *p < 0.05 compared to the control group (PBS)

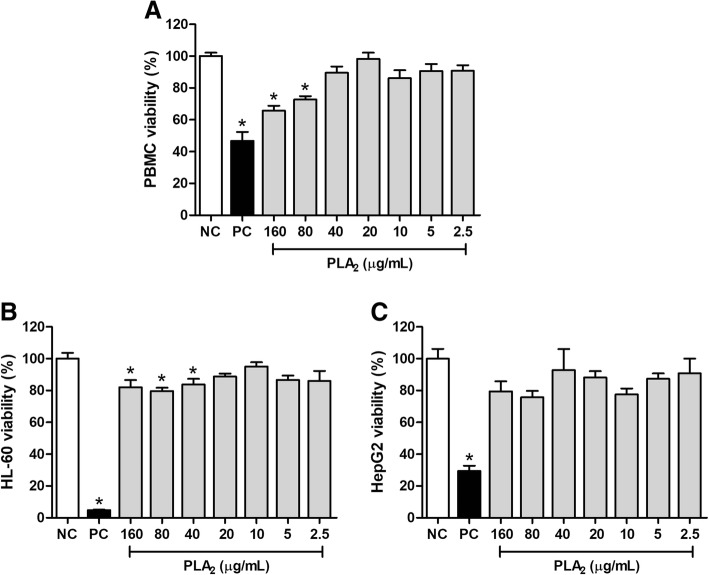

Cytotoxic effects

The cytotoxic effects of BJ-PLA2-I were assessed by treating normal cells (PBMC) or tumor cell lines (HL-60 and HepG2) with the toxin at different concentrations (2.5–160 μg/mL), followed by the determination of their cell viability. The results showed that BJ-PLA2-I was cytotoxic to PBMC at the two highest concentrations evaluated (80 and 160 μg/mL), as shown by the significant reduction in the PBMC viability in comparison to the negative control (Fig. 10a).

Fig. 10.

Evaluation of the cytotoxic effects induced by BJ-PLA2-I on normal and tumor cells. Cell viability of PBMC (a), HL-60 (b) and HepG2 (c) was assessed by the MTT method after a 24 h stimulation period with BJ-PLA2-I at different concentrations (2.5–160 μg/mL). Cells treated only with sterile PBS were used as negative controls (NC). The positive controls (PC) received cisplatin (Incel, Darrow®) at the final concentration of 250 μg/mL. Results were expressed as mean percentages (in relation to the negative control, considered as 100%) ± SD (n = 3) of two independent experiments. *p < 0.05 compared to the negative control (NC)

Regarding the tumor cell lines, BJ-PLA2-I significantly reduced the viability of HL-60 cells at the three highest concentrations assayed (40, 80 and 160 μg/mL) (Fig. 10b). HepG2 cell viability, on the other hand, was not altered by treatment with any of the BJ-PLA2-I concentrations evaluated (Fig. 10c).

Discussion

Our study described the isolation and characterization of an acidic PLA2 from B. jararaca venom, which we named BJ-PLA2-I. Comparing our results with those described by Serrano et al. [28] for BJ-PLA2, an acidic PLA2 also from B. jararaca venom, we have strong evidence to indicate that both are the same toxin: molecular mass of 14,276 Da for BJ-PLA2-I vs. 14,289 Da for BJ-PLA2, besides 100% identity in the 60 first amino acid residues from their N-terminal and inhibition of the ADP-induced platelet aggregation with IC50 ~ 20.5 μg/mL [28]. However, as we did not determine the full amino acid sequence of our toxin, we chose to name it differently, specifically BJ-PLA2-I.

Although we used different purification procedures to obtain BJ-PLA2-I in comparison to Serrano et al. [28], the final yield for its purification was also very low (0.2% for BJ-PLA2-I vs. 0.35% for BJ-PLA2), which indicates that this toxin represents a very small fraction of the total protein content of B. jararaca venom. This is consistent with previous proteomic data on this venom, showing that PLA2s only represent about 3% of its protein content, a very low percentage when compared to other Bothrops venoms, such as that of B. jararacussu (~ 20% of PLA2s) [29].

BJ-PLA2-I showed high catalytic activity as evaluated by the phospholipase assays, which is consistent with the presence of the Asp49 residue and its classification as an acidic PLA2. Several other acidic PLA2s from Bothrops venoms have been described as exerting high catalytic activity, including Bl-PLA2 (B. leucurus) [30], Bp-PLA2 (B. pauloensis) [31], BpirPLA2-I (B. pirajai) [32], BmooPLA2 (B. moojeni) [33], BE-I-PLA2 (B. erithromelas) [34], MTX-I (B. brazili) [35] and BatroxPLA2 (B. atrox) [22].

Another BJ-PLA2-I feature we observed was its ability to inhibit the ADP-induced platelet aggregation. Numerous snake venom PLA2s have been reported to act on platelet functions, which allowed their classification into 3 groups: class A includes the PLA2s able to induce platelet aggregation; class B, PLA2s that inhibit platelet aggregation induced by several agonists; and class C, PLA2s that present biphasic responses in platelets (pro- and anti-aggregating properties) [36]. According to our results, BJ-PLA2-I can be classified into class B, along with other PLA2s such as BpirPLA2-I (B. pirajai) [32], BthA-I-PLA2 (B. jararacussu) [37], BE-I-PLA2 (B. erythromelas) [34], BpPLA2-TXI (B. pauloensis) [31] and BmooPLA2 (B. moojeni) [33].

Once purified and characterized, BJ-PLA2-I was assessed as to its inflammatory effects. This evaluation is important since inflammation is a typical process in envenomations by the Viperidae and Crotalidae snake families, whose effects triggered by the inflammatory reactions have not been properly neutralized by the usual anti-ophidian serum therapy [30, 38–40]. Furthermore, PLA2s are described as one of the major toxin classes responsible for the inflammatory effects induced after snake envenomations [41].

The inflammatory potential of BJ-PLA2-I was initially assessed by in vivo leukocyte infiltration experiments. Leukocyte migration is a process involving several steps that are mediated by a dynamic of interaction between adhesion molecules expressed by leukocytes and endothelial cells, an expression that is regulated by cytokines and chemokines [42].

In general, administration of BJ-PLA2-I induced pronounced leukocyte infiltration in the peritoneal cavity of mice, formed mainly by neutrophils in the first hours (2 and 4 h) and by mononuclear cells after 24 h. These effects are not surprising since several studies have already shown that toxins from different classes (including PLA2s, serine and metalloproteases, L-amino acid oxidases and cysteine-rich secretory proteins) can promote inflammatory responses related to the infiltration of leukocytes [24, 43–46]. Interestingly, some studies have shown that catalytically inactive PLA2s (Lys49 PLA2s) can also induce leukocyte migration similar to those of catalytically active enzymes (Asp49 PLA2s), which suggests that the catalytic activity is not strictly necessary to trigger inflammatory responses, although it may contribute to these effects [6, 41, 47]. This is reinforced by studies using PLA2s chemically modified by BPB (p-bromophenacyl bromide, a classic PLA2 inhibitor), which demonstrated that these molecules did not lose their inflammatory effects [6, 48].

Besides inducing leukocyte infiltration, BJ-PLA2-I was also involved in the increased production of inflammatory mediators, including some cytokines (IL-6 and IL-1β) and eicosanoids (PGE2), and increased levels of total proteins in the peritoneum of mice, which indicate extravasation of proteins due to possible edematogenic effects of the toxin. On the other hand, levels of LTB4, IL-10, TNF-α and nitric oxide were not altered after stimulation with BJ-PLA2-I. Taking all these findings into account, the results for BJ-PLA2-I indicate a local inflammatory response, similar to the ones previously described for other Asp49 PLA2s from Bothrops venoms, such as BatroxPLA2 (B. atrox) [24], MT-III (B. asper) [6]; Bl-PLA2 (B. leucurus) [30] and Bleu-TX-III (B. leucurus) [49].

Activated leukocytes release a broad spectrum of cytokines, as well as proteins that contribute to the inflammatory process. The cytokines IL-6, IL-10, IL-1β and TNF-α are the main regulators of the inflammatory response, being able to induce fever, expression of adhesion molecules and activation of T and B cells [50]. Inflammatory events can also be attributed to the release of lipid mediators, including prostaglandins, thromboxanes and leukotrienes [12, 51]. PGE2 is an important member of the prostaglandin family that plays several roles in inflammation, exerts immunomodulatory effects, acts as a potent vasodilator and induces bradykinins. PGE2 is also known to suppress production of TNF-α, in addition to inhibiting T cell proliferation [52, 53]. Considering that TNF-α induces the synthesis of substances that cause tissue damage, such as nitric oxide [54], the increased levels of PGE2 induced by BJ-PLA2-I could be related to the unaltered levels of TNF-α and nitric oxide. In addition, production of PGE2 but not of LTB4 might indicate that BJ-PLA2-I-induced inflammation is related to the cyclooxygenase (COX) pathway instead of the lipoxygenase (LOX) one.

In our study, we showed that, overall, BJ-PLA2-I presented low cytotoxic effects on normal (PBMC) and tumor cells (HL-60 and HepG2), with viabilities mostly varying between 70 and 80% even at the highest concentrations. Such low cytotoxic effects have been attributed to other acidic PLA2s as well. De Albuquerque Modesto et al. [34] evaluated the cytotoxic potential of BE-I-PLA2, an acidic PLA2 from B. erithromelas venom, in human umbilical vein cells (HUVEC), showing that this PLA2 was not toxic to these normal human cells. Similar effects were described by Nunes et al. [30] for Bl-PLA2, an acidic PLA2 from the B. leucurus venom, which displayed low cytotoxicity to PBMC. On the other hand, there are also reports of acidic PLA2s with significant cytotoxic effects on different tumor cell lines. Roberto et al. [37] assessed the cytotoxic potential of BthA-I-PLA2 from B. jararacussu venom against three tumor cell lines: Jurkat (leukemic cells), SK-BR-3 (human breast tumor cells) and EAT (Ehrlich ascites tumor cells). BthA-I-PLA2 at 100 μg/mL was demonstrated to be highly cytotoxic to Jurkat and SK-BR-3 (50 and 30% viability, respectively), while the viability of EAT cells was less affected (80% viability). Likewise, the acidic PLA2s BmooTX-I from B. moojeni venom [33] and MTX-I from B. brazili venom [35], at a concentration of 100 μg/mL, reduced the viability of Jurkat cells to 50 and 40%, respectively.

Despite inducing low cytotoxicity in the tumor cells evaluated, we observed that BJ-PLA2-I significantly reduced the viability of HL-60 cells, but not that of HepG2 cells. This different cytotoxic specificity may be related to several factors, including the fact that HL-60 cells grow as a suspension, while HepG2 are adherent cells. Nevertheless, the opposite behavior was described for nigexine, a PLA2 from Naja nigricollis venom, which was more cytotoxic to adherent cell lines (epithelial FL and C-13 T neuroblastoma cells) than to those in suspension (HL-60) [55].

Thus, although some snake venom PLA2s can present cytotoxic effects, most of these enzymes do not exhibit this activity, which strongly suggests that other mechanisms, unrelated to the PLA2 catalytic activity, are involved in the cytotoxicity [55, 56]. In fact, Lomonte et al. [57] identified a region near the C-terminal of Lys49 PLA2 homologues responsible for their cytotoxic effects. This would explain why some Lys49 PLA2s, which typically lack catalytic activity, are also described as cytotoxic molecules [7, 56].

Conclusions

BJ-PLA2-I was successfully isolated from B. jararaca venom and characterized as an acidic Asp49 PLA2 that induces acute local inflammation in mice and low cytotoxicity in normal (PBMC) and tumor cells (HL-60 and HepG2). The information obtained in the present work brings significant contributions to the studies of animal toxins, both in relation to Bothrops envenomations and the understanding of the mechanisms involved in the biological effects induced by PLA2s. Thus, BJ-PLA2-I may contribute to the biotechnology field, by serving as a molecular model for the formulation of more effective drugs used in the treatment of various diseases or even for developing novel strategies for anti-ophidian therapy.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Sante E.I. Carone and Luiz F.F. Tucci from FCFRP-USP for their technical support, and to Prof. Dr. José César Rosa and the Protein Chemistry Center, Medical School of Ribeirão Preto-USP, for the mass spectrometry analyses.

Funding

Financial support was provided by the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES), the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP, grant #2011/23236–4) and the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq, Proc. 476,932/2012–2). Moreover, this publication was supported by the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) through Programa Editoração CAPES (Edital No. 13/2016, No. do Auxílio 0722/2017, No. do Processo 88,881.142062/2017–01) and from the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) (Programa Editorial CNPq/CAPES process No. 26/2017, Proc. No. 440954/2017–7).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Authors’ contributions

RCAC, DLM, TRC, KFZ, MAS and NASF performed the experiments of this study. RCAC and DLM analyzed the results and wrote the manuscript. LHF and SVS conceived, supervised and critically discussed the study, and contributed with materials and infrastructure. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Animal care procedures were performed according to the Brazilian College of Animal Experimentation (COBEA) guidelines and the experimental protocols were approved by the Committee for Ethics on Animal Use (CEUA) from FCFRP-USP (Proc. n° 2012.1.414.53.4). All experiments involving human blood were in accordance with the authorization of the Research Ethics Committee of FCFRP-USP (CEP/FCFRP protocol n° 353).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Rafhaella C. A. Cedro, Email: r.cedroa@gmail.com

Danilo L. Menaldo, Email: menaldo@fcfrp.usp.br

Tássia R. Costa, Email: tassiarc@fcfrp.usp.br

Karina F. Zoccal, Email: karina_zoccal4@hotmail.com

Marco A. Sartim, Email: marcosartim@hotmail.com

Norival A. Santos-Filho, Email: drnorival@yahoo.com

Lúcia H. Faccioli, Email: faccioli@fcfrp.usp.br

Suely V. Sampaio, Phone: +55 (16) 3315-4286, Email: suvilela@usp.br

References

- 1.Dennis EA. Diversity of group types, regulation, and function of phospholipase A2. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(18):13057–13060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murakami M, Taketomi Y, Miki Y, Sato H, Hirabayashi T, Yamamoto K. Recent progress in phospholipase A2 research: from cells to animals to humans. Prog Lipid Res. 2011;50(2):152–192. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Six DA, Dennis EA. The expanding superfamily of phospholipase A2 enzymes: classification and characterization. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1488(1–2):1–19. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00105-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ownby CL, Selistre de Araujo HS, White SP, Fletcher JE. Lysine 49 phospholipase A2 proteins. Toxicon. 1999;37(3):411–445. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(98)00188-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ward RJ, de Azevedo WF, Jr, Arni RK. At the interface: crystal structures of phospholipases A2. Toxicon. 1998;36(11):1623–1633. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(98)00155-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zuliani JP, Fernandes CM, Zamuner SR, Gutiérrez JM, Teixeira CF. Inflammatory events induced by Lys-49 and Asp-49 phospholipases A2 isolated from Bothrops asper snake venom: role of catalytic activity. Toxicon. 2005;45(3):335–346. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prinholato da Silva C, Costa TR, Paiva RMA, Cintra ACO, Menaldo DL, Antunes LMG, et al. Antitumor potential of the myotoxin BthTX-I from Bothrops jararacussu snake venom: evaluation of cell cycle alterations and death mechanisms induced in tumor cell lines. J Venom Anim Toxins incl Trop Dis. 2015;21:44. doi: 10.1186/s40409-015-0044-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corrêa EA, Kayano AM, Diniz-Sousa R, Setúbal SS, Zanchi FB, Zuliani JP, et al. Isolation, structural and functional characterization of a new Lys49 phospholipase A2 homologue from Bothrops neuwiedi urutu with bactericidal potential. Toxicon. 2016;115:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2016.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zelanis A, Andrade-Silva D, Rocha MM, Furtado MF, Serrano SMT, Junqueira-de-Azevedo ILM, et al. A transcriptomic view of the proteome variability of newborn and adult Bothrops jararaca snake venoms. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6(3):e1554. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gutiérrez JM, Lomonte B. Phospholipases A2: unveiling the secrets of a functionally versatile group of snake venom toxins. Toxicon. 2013;62:27–39. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun GY, Shelat PB, Jensen MB, He Y, Sun AY, Simonyi A. Phospholipases A2 and inflammatory responses in the central nervous system. NeuroMolecular Med. 2010;12(2):133–148. doi: 10.1007/s12017-009-8092-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zamuner SR, Zuliani JP, Fernandes CM, Gutierrez JM, de Fatima PTC. Inflammation induced by Bothrops asper venom: release of proinflammatory cytokines and eicosanoids, and role of adhesion molecules in leukocyte infiltration. Toxicon. 2005;46(7):806–813. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cummings BS. Phospholipase A2 as targets for anti-cancer drugs. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;74(7):949–959. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mashima T, Seimiya H, Tsuruo T. De novo fatty-acid synthesis and related pathways as molecular targets for cancer therapy. Br J Cancer. 2009;100(9):1369–1372. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Araya C, Lomonte B. Antitumor effects of cationic synthetic peptides derived from Lys49 phospholipase A2 homologues of snake venoms. Cell Biol Int. 2007;31(3):263–268. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227(5259):680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arantes EC, Prado WA, Sampaio SV, Giglio JR. A simplified procedure for the fractionation of Tityus serrulatus venom: isolation and partial characterization of TsTX-IV, a new neurotoxin. Toxicon. 1989;27(8):907–916. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(89)90102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murakami MT, Gabdoulkhakov A, Genov N, Cintra AC, Betzel C, Arni RK. Insights into metal ion binding in phospholipases A2: ultra high-resolution crystal structures of an acidic phospholipase A2 in the Ca2+ free and bound states. Biochimie. 2006;88(5):543–549. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2005.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zimmermann L, Stephens A, Nam SZ, Rau D, Kübler J, Lozajic M, et al. A completely reimplemented MPI bioinformatics toolkit with a new HHpred server at its core. J Mol Biol. 2018;430(15):2237–2243. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2017.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Webb B, Sali A. Comparative protein structure modeling using MODELLER. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2016;54:5.6.1–5.5.6. doi: 10.1002/cpbi.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gutierrez JM, Avila C, Rojas E, Cerdas L. An alternative in vitro method for testing the potency of the polyvalent antivenom produced in Costa Rica. Toxicon. 1988;26(4):411–413. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(88)90010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Menaldo DL, Jacob-Ferreira AL, Bernardes CP, Cintra ACO, Sampaio SV. Purification procedure for the isolation of a P-I metalloprotease and an acidic phospholipase A2 from Bothrops atrox snake venom. J Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis. 2015;21:28. doi: 10.1186/s40409-015-0027-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Born GV. Aggregation of blood platelets by adenosine diphosphate and its reversal. Nature. 1962;194:927–929. doi: 10.1038/194927b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Menaldo DL, Bernardes CP, Zoccal KF, Jacob-Ferreira AL, Costa TR, Del Lama MP, et al. Immune cells and mediators involved in the inflammatory responses induced by a P-I metalloprotease and a phospholipase A2 from Bothrops atrox venom. Mol Immunol. 2017;85:238–247. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2017.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Green LC, Ruiz de Luzuriaga K, Wagner DA, Rand W, Istfan N, Young VR, et al. Nitrate biosynthesis in man. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78(12):7764–7768. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.12.7764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Costa TR, Menaldo DL, Prinholato da Silva C, Sorrechia R, de Albuquerque S, Pietro RC, et al. evaluating the microbicidal, antiparasitic and antitumor effects of CR-LAAO from Calloselasma rhodostoma venom. Int J Biol Macromol. 2015;80:489–497. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65(1–2):55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Serrano SM, Reichl AP, Mentele R, Auerswald EA, Santoro ML, Sampaio CA, et al. A novel phospholipase A2, BJ-PLA2, from the venom of the snake Bothrops jararaca: purification, primary structure analysis, and its characterization as a platelet-aggregation-inhibiting factor. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1999;367(1):26–32. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sousa LF, Nicolau CA, Peixoto PS, Bernardoni JL, Oliveira SS, Portes-Junior JA, et al. Comparison of phylogeny, venom composition and neutralization by antivenom in diverse species of Bothrops complex. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7(9):e2442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nunes DC, Rodrigues RS, Lucena MN, Cologna CT, Oliveira AC, Hamaguchi A, et al. Isolation and functional characterization of proinflammatory acidic phospholipase A2 from Bothrops leucurus snake venom. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol. 2011;154(3):226–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rodrigues RS, Izidoro LFM, Teixeira SS, Silveira LB, Hamaguchi A, Homsi-Brandeburgo MI, et al. Isolation and functional characterization of a new myotoxic acidic phospholipase A2 from Bothrops pauloensis snake venom. Toxicon. 2007;50(1):153–165. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Teixeira SS, Silveira LB, da Silva FM, Marchi-Salvador DP, Silva FP, Jr, Izidoro LF, et al. Molecular characterization of an acidic phospholipase A2 from Bothrops pirajai snake venom: synthetic C-terminal peptide identifies its antiplatelet region. Arch Toxicol. 2011;85(10):1219–1233. doi: 10.1007/s00204-011-0665-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Santos-Filho NA, Silveira LB, Oliveira CZ, Bernardes CP, Menaldo DL, Fuly AL, et al. A new acidic myotoxic, anti-platelet and prostaglandin I2 inductor phospholipase A2 isolated from Bothrops moojeni snake venom. Toxicon. 2008;52(8):908–917. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2008.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Albuquerque Modesto JC, Spencer PJ, Fritzen M, Valença RC, Oliva MLV, da Silva MB, et al. BE-I-PLA2, a novel acidic phospholipase A2 from Bothrops erythromelas venom: isolation, cloning and characterization as potent anti-platelet and inductor of prostaglandin I2 release by endothelial cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;72(3):377–384. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Costa TR, Menaldo DL, Oliveira CZ, Santos-Filho NA, Teixeira SS, Nomizo A, et al. Myotoxic phospholipases A2 isolated from Bothrops brazili snake venom and synthetic peptides derived from their C-terminal region: cytotoxic effect on microorganism and tumor cells. Peptides. 2008;29(10):1645–1656. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2008.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kini RM, Evans HJ. Effects of phospholipase A2 enzymes on platelet aggregation. In: Kini RM, editor. Venom phospholipase A2 enzymes: structure, function and mechanism. Wiley: Chichester; 1997. pp. 369–387. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roberto PG, Kashima S, Marcussi S, Pereira JO, Astolfi-Filho S, Nomizo A, et al. Cloning and identification of a complete cDNA coding for a bactericidal and antitumoral acidic phospholipase A2 from Bothrops jararacussu venom. Protein J. 2004;23(4):273–285. doi: 10.1023/b:jopc.0000027852.92208.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carneiro AS, Ribeiro OG, Cabrera WH, Vorraro F, De Franco M, Ibanez OM, et al. Bothrops jararaca venom (BjV) induces differential leukocyte accumulation in mice genetically selected for acute inflammatory reaction: the role of host genetic background on expression of adhesion molecules and release of endogenous mediators. Toxicon. 2008;52(5):619–627. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moreira V, Zamuner SR, Wallace JL, Teixeira C. de F. Bothrops jararaca and Crotalus durissus terrificus venoms elicit distinct responses regarding to production of prostaglandins E2 and D2, and expression of cyclooxygenases. Toxicon. 2007;49(5):615–624. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Teixeira C, Cury Y, Moreira V, Picolo G, Chaves F. Inflammation induced by Bothrops asper venom. Toxicon. 2009;54(1):67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Teixeira CFP, Landucci ECT, Antunes E, Chacur M, Cury Y. Inflammatory effects of snake venom myotoxic phospholipases A2. Toxicon. 2003;42(8):947–962. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Biedermann T, Kneilling M, Mailhammer R, Maier K, Sander CA, Kollias G, et al. Mast cells control neutrophil recruitment during T cell-mediated delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions through tumor necrosis factor and macrophage inflammatory protein 2. J Exp Med. 2000;192(10):1441–1452. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.10.1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Menaldo DL, Bernardes CP, Pereira JC, Silveira DS, Mamede CC, Stanziola L, et al. Effects of two serine proteases from Bothrops pirajai snake venom on the complement system and the inflammatory response. Int Immunopharmacol. 2013;15(4):764–771. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2013.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bernardes CP, Menaldo DL, Mamede CC, Zoccal KF, Cintra AC, Faccioli LH, et al. Evaluation of the local inflammatory events induced by BpirMP, a metalloproteinase from Bothrops pirajai venom. Mol Immunol. 2015;68(2 Pt B):456–464. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2015.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Costa TR, Menaldo DL, Zoccal KF, Burin SM, Aissa AF, Castro FA, et al. CR-LAAO, an L-amino acid oxidase from Calloselasma rhodostoma venom, as a potential tool for developing novel immunotherapeutic strategies against cancer. Sci Rep. 2017;7:42673. doi: 10.1038/srep42673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lodovicho ME, Costa TR, Bernardes CP, Menaldo DL, Zoccal KF, Carone SE, et al. Investigating possible biological targets of Bj-CRP, the first cysteine-rich secretory protein (CRISP) isolated from Bothrops jararaca snake venom. Toxicol Lett. 2017;265:156–169. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gambero A, Landucci EC, Toyama MH, Marangoni S, Giglio JR, Nader HB, et al. Human neutrophil migration in vitro induced by secretory phospholipases A2: a role for cell surface glycosaminoglycans. Biochem Pharmacol. 2002;63(1):65–72. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00841-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.de Castro RC, Landucci EC, Toyama MH, Giglio JR, Marangoni S, De Nucci G. Leucocyte recruitment induced by type II phospholipases A2 into the rat pleural cavity. Toxicon. 2000;38(12):1773–1785. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(00)00107-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marangoni FA, Ponce-Soto LA, Marangoni S, Landucci ECT. Unmasking snake venom of Bothrops leucurus: purification and pharmacological and structural characterization of new PLA2 Bleu TX-III. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:ID 941467. doi: 10.1155/2013/941467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kida Y, Kobayashi M, Suzuki T, Takeshita A, Okamatsu Y, Hanazawa S, et al. Interleukin-1 stimulates cytokines, prostaglandin E2 and matrix metalloproteinase-1 production via activation of MAPK/AP-1 and NF-kappaB in human gingival fibroblasts. Cytokine. 2005;29(4):159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Farsky SH, Walber J, Costa-Cruz M, Cury Y, Teixeira CF. Leukocyte response induced by Bothrops jararaca crude venom: in vivo and in vitro studies. Toxicon. 1997;35(2):185–193. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(96)00135-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Knudsen PJ, Dinarello CA, Strom TB. Prostaglandins posttranscriptionally inhibit monocyte expression of interleukin 1 activity by increasing intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate. J Immunol. 1986;137(10):3189–3194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nataraj C, Thomas DW, Tilley SL, Nguyen MT, Mannon R, Koller BH, et al. Receptors for prostaglandin E2 that regulate cellular immune responses in the mouse. J Clin Invest. 2001;108(8):1229–1235. doi: 10.1172/JCI13640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dinarello CA. Cytokines as mediators in the pathogenesis of septic shock. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1996;216:133–165. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-80186-0_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chwetzoff S, Tsunasawa S, Sakiyama F, Ménez A. Nigexine, a phospholipase A2 from cobra venom with cytotoxic properties not related to esterase activity. Purification, amino acid sequence, and biological properties. J Biol Chem. 1989;264(22):13289–13297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gebrim LC, Marcussi S, Menaldo DL, de Menezes CS, Nomizo A, Hamaguchi A, et al. Antitumor effects of snake venom chemically modified Lys49 phospholipase A2-like BthTX-I and a synthetic peptide derived from its C-terminal region. Biologicals. 2009;37(4):222–229. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lomonte B, Moreno E, Tarkowski A, Hanson LA, Maccarana M. Neutralizing interaction between heparins and myotoxin II, a lysine 49 phospholipase A2 from Bothrops asper snake venom. Identification of a heparin-binding and cytolytic toxin region by the use of synthetic peptides and molecular modeling. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(47):29867–29873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fernández J, Gutiérrez JM, Angulo Y, Sanz L, Juárez P, Calvete JJ, et al. Isolation of an acidic phospholipase A2 from the venom of the snake Bothrops asper of Costa Rica: biochemical and toxicological characterization. Biochimie. 2010;92(3):273–283. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.