Abstract

Objectives:

We examined cognitive function in non-demented, non-delirious, older adults one-year post hip fracture.

Design:

Prospective observational study.

Setting and Participants:

386 hip fracture patients, aged 60 years and older with no history of cognitive impairment such as clinical dementia or persistent delirium, recruited from eight area hospitals 2–3 days after hip surgery (week 0); and 101 older adults with no recent acute medical events for control comparison.

Measurements:

Cognitive function was examined with the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) and Short Blessed Test (SBT) at weeks 0 (SBT only), 4, and 52 using a repeated measures mixed model analysis. Baseline predictor variables included demographics, personality, genetic factors, and depression symptom level.

Results:

Hip fracture participants had lower cognitive scores than healthy comparisons. Cognitive scores improved in the hip fracture group relative to healthy comparison participants from week 4 to 52. The only significant predictor of cognitive improvement after hip fracture was education: individuals with college education showed cognitive improvement by week 52, while those with high school or less did not.

Conclusions:

Non-demented, non-delirious older adults suffering hip fracture have poorer cognitive function immediately after the fracture, but then exhibit cognitive improvement over the ensuing year, especially among those with high education. This demonstrates brain resilience in older adults even in the context of advanced age, medical illness, and frailty.

Keywords: hip fracture, delirium, cognitive decline

Introduction:

Falls in older adults are common and debilitating. In the US alone, costs related to falls amounted to over 31 billion dollars; fall-related injury is among the top 20 most expensive medical conditions (1). One of the most serious fall injuries is hip fracture, seen in over 300,000 older adults yearly in the US (2). Hip fracture occurs more frequently in women, older adults, those with frailty associated with lower bone density (3), and those with neurodegenerative brain diseases such as Alzheimer’s dementia (4). Falls are also more likely to occur in those who have neuropathology even without clinically apparent cognitive impairment (e.g. pre-clinical dementia) (5). Hip fracture can result in severe disability and impairment (6) and ultimately, leads to poorer health, mobility, quality of life, loss of independence, as well as higher rates of institutionalization (7).

The maintenance of cognitive function despite the neurophysiological insults that accompany advancement in age, trauma, and multiple medical comorbidities is an indication of brain resilience (8). Certain factors contribute to brain resilience including higher education levels, physical fitness, conscientiousness, and multilingualism (8). Because these resilience factors predict prevention of longterm cognitive decline, they might also predict cognitive recovery after an insult such as hip fracture.

Cognitive impairment after hip fracture is common and etiologically complex (9, 10); it can reflect preexisting cognitive impairment (i.e. dementia or mild cognitive impairment) (10), that can serve to increase risk of fall and fracture in the first place, persistent delirium, which may persist for months (11), or postoperative cognitive impairment in the absence of persistent delirium (10). Much is already known about the course of hip fracture patients with pre-existing dementia or persistent delirium: both are extremely common, leading to cognitive and functional decline in the year post-fracture (12). In this manner, the poor outcomes (cognitive and functional) seen after hip fracture might be better chalked up to pre-existing brain disease rather than the hip fracture itself.

Far less is known about the course of cognitive impairment and recovery post-operatively attributable to hip fracture itself, as none of the aforementioned studies controlled for the presence of pre-existing neurocognitive dysfunction. Previous studies have shown that inflammatory responses associated with medical conditions accounted for variability in functional and outcomes as well as new onset depressive symptoms, which also contribute to suboptimal recovery (13), (14). Significant increases in serum inflammatory mediators, CRP and IL-6, in elderly hip fracture patients were found in patients with impaired mental status (15). However, little is known regarding the effect of hip fracture on cognitive function in older adults without persistent delirium or dementia, both of which are well-known indicators of subsequent cognitive decline. To examine the course of cognitive change attributable to hip fracture itself, these common co-occurring conditions would need to be excluded. Therefore, we conducted a longitudinal study of older adults with hip fracture but no peri-operative delirium or preexisting cognitive impairment. In this study, we examined neurocognitive function via an extensive neurocognitive assessment including the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) and the Short Blessed Test (SBT) in non-demented, non-delirious older adults with hip fracture and compared their results to those of healthy comparison participants. We hypothesized that cognitive function would be lower immediately after hip fracture, but would then recover during the ensuing year. A second goal was to examine predictors of cognitive function after hip fracture, which might identify brain resilience factors in this advanced-age, medically ill, and generally frail population. Age, education, depression, genetics, personality and lifestyle factors such as smoking and alcohol use have all been previously implicated as predictors of cognitive function (8) and are applied in this study.

Methods:

This was a prospective longitudinal study of cognitive, affective, and genetic predictors of hip fracture recovery funded by NIMH (16). Adults aged 60+ with hip fracture were enrolled from eight hospitals in Saint Louis. The institutional review board at Washington University School of Medicine approved the study and all participants provided written informed consent. Healthy comparison participants were enrolled from the community and included those without a hip fracture in the prior year, or a severe medical event or hospitalization within the prior six months. The comparison group served as a benchmark for two main purposes: (1) to determine whether at baseline, the hip fracture group was cognitively normal or impaired, and (2) to determine whether cognition in the hip fracture group remained normal or experienced accelerated decline (compared with the control group) over one year. Healthy comparison participants were recruited via the university’s research registry, self-referrals, presentations, as well as advertisements.

Inclusion criteria included patients aged 60 years and older admitted with a diagnosis of hip fracture that required surgical repair. Participants were excluded if they had cognitive impairment; i.e., history of clinical dementia or delirium that did not clear within one to two days of hip surgery. This was ascertained by a chart review (e.g., for dementia diagnosis which was an exclusion), the delirium rating scale (17) assessment with the Short Blessed Test (scores >12 excluded individuals for this study), and an assessment of understanding of the study. For those with cognitive impairment, we continued to assess them throughout their hospitalization, excluding them if they remained cognitively impaired at their discharge. In addition, we excluded participants who were unable to cooperate with the protocol; had major depressive disorder, as assessed by the Structural Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Medical Disorders IV, at the time of the fracture; metastatic cancer; significant language, visual or hearing limitations; homes more than an hour away; inoperable fractures; and those who were taking ‘depressogenic’ medications; interferon or corticosteroids. Depressive symptoms were measured by trained raters via the MADRS at baseline (two days after surgery), week 1, 2, 4 and 52. The MADRS was conducted in person at baseline; weeks 4 and 52, while the rest of the time points were conducted by phone. MADRS scores at baseline were retrospective, as participants described their depressive symptoms for the week prior to hip fracture or entry to the study for healthy comparisons. Higher MADRS scores were indicative of worse depressive symptoms.

Participants were followed for 52 weeks with assessments being conducted in person at baseline (i.e. week 0: 2–3 days after surgery and while still hospitalized), as well as weeks 4 and 52 after discharge. Healthy comparison participants completed the same measures at the same time points as the hip fracture participants.

Cognitive Measures:

Cognitive function was examined by the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS), which was our primary measure for this analysis. The RBANS measures global neurocognitive functioning (18,19). It was originally designed to detect cognitive decline and dementia in older adults, and it has an alternate form to reduce practice effects when it is repeated (18). The RBANS consists of 12 tests that aggregate into five different domains. The first domain assesses immediate memory, which consists of two subtests, list learning and story memory. The second measures visuospatial and constructional abilities, and consists of two subtests, figure copy and line orientation. The third measures language abilities, and consists of picture naming as well as semantic fluency. The fourth assesses attention, and consists of two sections, digit span forward as well as coding. The fifth assesses delayed memory and consists of four subsections: list recall, list recognition, story recall, and figure recall. The RBANS derived scores consist of a total composite score as well as the five component scores for each index, which in turn is derived from a combination of each subtest score. Higher RBANS scores denote better cognitive function. In this study, the RBANS was conducted at weeks 4 and 52. Subjects were tested at 4 weeks, allowing appropriate time for recovery from delirium or other acute medical changes.

In addition, the Short Blessed Test (SBT), also referred to as the Orientation-Memory- Concentration test (20) was used as a screening measure to assess cognitive function immediately after hip fracture at baseline (when a comprehensive battery such as the RBANS would be infeasible), as well as weeks 4 and 52, which allowed us to measure longitudinal cognitive changes starting from the early postoperative period, similar to other research (12). The SBT is a brief assessment of orientation, registration, and attention. Scores range from 0–28, and higher SBT scores indicate worse impairment. In healthy outpatients, a cut off of 10 or higher typically signifies significant cognitive impairment i.e. dementia (20,21); we used a higher cutoff of 13 in this study because we were assessing acutely ill hospitalized hip fracture patients.

Other Measures:

Sociodemographic data such as age, education level, race, gender, pain score, smoking status, alcohol use, as well as concurrent use of psychotropic medications were collected at baseline. The Hip Fracture Recovery (HFR) score was used to measure functional recovery (22) and was conducted at weeks 0, 4, 12, 26, and 52. The Cumulative Illness Rating Scale for Geriatric (CIRS-G) score was used to quantify chronic illness morbidity and burden and was conducted at baseline.

We assessed personality with the mini-IPIP (International Personality Item Pool - Five Factor Model Measure)(23,24). It consists of twenty questions, four of which test each of the Big Five factors of personality; Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Neuroticism, and Intellect/Imagination (25). We chose conscientiousness as a measure of personality due to its protective properties against dementia (26,27).

In addition, DNA was extracted from participants’ blood samples and was genotyped for apolipoprotein E (APOE) E4 allele status and brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) valine (Val) to methionine (Met polymorphism (Val66Met; refSNP: rs6265) as these are known sources of variability of cognitive function in older adults.

Statistical Analysis:

Baseline differences between hip fracture subjects and healthy comparisons were compared using t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square for categorical variables.

The primary analysis was for the total RBANS, which could be thought of as a single composite measure of cognitive function. As this analysis had a significant finding, the RBANS sub-scores are reported to elucidate the specific cognitive functions showing the biggest differences. A repeated measures mixed model analysis was used to compare individual RBANS subtest scores, and total RBANS score for hip fracture and healthy comparison groups at week 4 and week 52. For patients unable to complete the RBANS due to cognitive impairment, we substituted the lowest measured score rather than treating it as missing. For other missing clinical and cognitive data we used multiple imputation based on other variables measured at that visit.

A mixed effect model was also used to compare SBT scores at baseline, week 4 and week 52.

Additionally, we re-ran the mixed effect models covarying for age, race, gender, APOE E4 genotype, BDNF Val66Met SNP and being on psychotropic medications.

Finally, we used generalized linear model to examine whether any of these variables predicted cognitive changes over time in the hip fracture sample: age, race, sex, APOE E4 genotype, BDNF Val66Met, MADRS score, educational level >12 years, pain score, smoking status, alcohol use, CIRS-G score, personality, and use of psychotropic drugs. Complete data were used in this analysis. Statistical analysis was performed via SAS version 9.4 (SAS System for Windows, Cary, NC) (28), and P<0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Results:

A total of 1856 hip fracture patients were screened for eligibility, of which 1207 were ineligible; 862 due to cognitive impairment, 27 due to current major depressive disorder, 159 due to language, visual or hearing barriers, and 159 miscellaneous. Another 155 patients declined to participate and 108 were lost to follow up or were unable to be administered the RBANS. As for healthy comparisons, 109 were screened for eligibility, of which 3 declined to participate and another 5 did not meet inclusion criteria. A total of 386 hip fracture participants and 101 non-fracture healthy comparison participants were included. Table 1 compares the groups in terms of baseline characteristics. There were no differences between hip fracture participants and healthy comparison participants in age, sex, race, treatment with any psychotropic medications, APOE E4 levels, and genotype frequencies of BDNF SNPs. Participants with hip fracture had less education than healthy comparisons, which was statistically significant.

Table 1:

Baseline Demographic and Key Clinical Characteristics of Participants with Hip Fractures and Healthy Comparisons.

| Healthy Comparison (n=101) |

Hip Fracture (n=386) |

Chi square/ t scores |

p-value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean years, SD) | 77.77 (7.38) | 77.80 (8.39) | −0.03 (DF=485) | 0.98 |

| Gender (n, %) | 1.48 (DF=1) | 0.22 | ||

| Male | 32 (31.7%) | 99 (25.6%) | ||

| Female | 69 (68.3%) | 287 (74.4%) | ||

| Race (n, %) | 1.88 (DF=1) | 0.39 | ||

| White | 92 (91.1%) | 362 (93.8%) | ||

| Non-White | 9 (8.9%) | 24 (6.2%) | ||

| Education, years* | 15.08 (2.79) | 13.18 (2.81) | 5.70 (DF=439) | <0.0001 |

| APOE E4 (n,%) | 0.04 (DF=1) | 0.84 | ||

| No | 65 (73.9%) | 254.(74.9%) | ||

| Yes | 23 (26.1%) | 85 (25.1%) | ||

| BDNF Val66Met (n, %) | 1.98 (DF=2) | 0.37 | ||

| Val/Val | 69 (69.0%) | 264 (70.0%) | ||

| Val/Met | 30 (30.0%) | 100 (26.5%) | ||

| Met/Met | 1 (1.0%) | 13 (3.4%) | ||

| Taking any psychotropic | ||||

| medication (n, %) | 1.46 (DF=1) | 0.23 | ||

| No | 80 (83.33%) | 296 (77.69%) | ||

| Yes | 16 (16.67%) | 85 (22.31%) |

t-test

Others use Chi-square test

Abbreviations: APOE E4, Apolipoprotein E4; BDNF, Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor; Val, valine; Met, methionine

Changes in cognitive function in the year after hip fracture

We assessed cognitive function longitudinally beginning four weeks after the fracture with the comprehensive RBANS battery. Table 2 summarizes the raw RBANS total and subtests scores for healthy comparison and hip fracture participants at weeks 4 and 52. The hip fracture participants had lower total RBANS scores than the healthy comparison group, and an increase (improvement) in scores from 4 to 52 weeks, relative to healthy comparisons. With respect to individual RBANS subtests, hip fracture participants had lower semantic fluency and figure recall than healthy comparisons.

Table 2:

Individual and Total Raw Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) Scores for Participants with Hip Fractures and Healthy Comparisons.

| Healthy Comparison** | Hip Fracture** | t* | DF | p-value* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 4 | Week 52 | Week 4 | Week 52 | timepoint* condition |

Timepoint* condition |

timepoint condition |

|

| RBANS total (SD) | 96.36 (13.85) | 96.19 (14.12) | 80.79 (14.18) | 83.60 (17.14) | 2.35 | 1170.2 | 0.02 |

| List Learning (SD) | 24.85 (5.04) | 24.67 (4.94) | 20.75 (5.81) | 21.15 (6.57) | 1.10 | 4798.1 | 0.27 |

| Story Memory (SD) | 15.44 (4.02) | 15.58 (3.87) | 12.71 (4.77) | 13.08 (4.95) | 0.65 | 1482.9 | 0.52 |

| Figure Copy (SD) | 13.83 (3.55) | 13.72 (3.81) | 11.67 (4.04) | 12.02 (4.38) | 1.06 | 1595 | 0.29 |

| Line Orientation (SD) | 15.82 (4.14) | 16.05 (3.98) | 13.22 (5.23) | 13.32 (5.41) | 0.12 | 2019.9 | 0.91 |

| Picture Naming (SD) | 9.66 (0.73) | 9.72 (0.66) | 9.48 (0.79) | 9.36 (1.39) | −0.89 | 5901.6 | 0.38 |

| Semantic Fluency (SD) | 19.85 (5.42) | 18.27 (4.87) | 16.24 (4.82) | 16.07 (5.52) | 2.56 | 1653.1 | 0.01 |

| Digit Span (SD) | 10.48 (2.51) | 10.93 (2.51) | 9.70 (2.48) | 9.87 (5.57) | −0.77 | 17549 | 0.44 |

| Coding (SD) | 37.89 (10.66) | 38.75 (9.94) ^ | 28.52 (10.71) | 29.07 (12.14) | 0.39 | 2035.5 | 0.69 |

| List Recall (SD) | 4.62 (2.75) | 5.02 (2.63) | 3.22 (2.63) | 3.54 (2.84) | −0.09 | 1354.7 | 0.93 |

| List Recognition (SD) | 18.99 (1.44) | 18.92 (1.47) | 17.84 (2.51) | 18.17 (2.39) | 1.32 | 1914.3 | 0.19 |

| Story Recall (SD) | 7.80 (2.77) | 7.98 (2.78) | 5.82 (2.98) | 6.15 (3.25) | 0.52 | 1046.3 | 0.60 |

| Figure Recall (SD) | 9.29 (4.25) | 8.79 (4.55) | 6.15 (4.29) | 6.72 (4.61) | 2.25 | 1106.1 | 0.02 |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; RBANS, Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status, DF: degrees of freedom

t and p-values are calculated from mixed models evaluating group by time interaction, after multiple imputation for missing data.

Observed mean (SD) without imputation

We also assessed cognitive function beginning immediately after the fracture using the SBT, a screening measure of cognitive impairment (higher scores indicate more impairment, with a score of 10 or greater generally indicating impairment at a level of dementia). SBT scores in hip fracture participants were 4.59 (SD=0.15) at baseline, 3.21 (SD=0.16) at week 4, and 3.82 (SD=0.17) at week 52, compared to 2.12 (SD=0.32), 1.37(SD=0.33) and 1.69 (SD=0.33) for the healthy comparison group. There was no significant group by time interaction, (F(df)=1.4(2,953) p= 0.25) but there was a significant group effect (F(df)=56(1,953) p<0.001) and a significant time effect, (F(df)=16(2,953) p<0.001): scores were higher (worse) in hip fracture patients, and they reduced over time in the entire sample.

Predictors of cognitive changes in the year after hip fracture

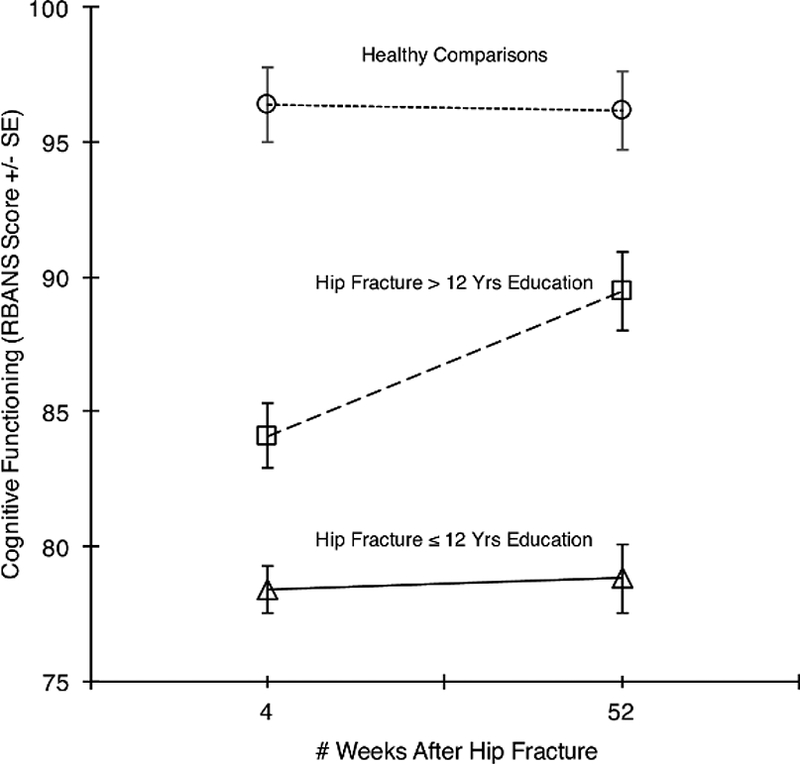

We examined several baseline patient characteristics and early post-fracture variables as predictors of cognitive change in the hip fracture group: age, sex, education level, race, depressive symptoms, MADRS, pain score, alcohol use, smoking status, CIRS-G score, APOE E4 status, BDNF status, and conscientiousness. Of these, only educational attainment predicted RBANS changes (see Figure 1); those with an above high school level education showed an increase, or improvement, in cognitive function, while those with high school or less did not.

Figure 1:

Changes in Cognitive Functioning in the Year following Hip Fracture, Stratified by Educational Attainment (>12 years versus ≤ 12 years). Individuals with higher educational level improved from week 4 to 52 after fracture, while those with high school or less did not. Cognitive functioning in healthy comparisons is shown as a reference condition. Vertical bars represent standard error.

Discussion:

We conducted a one-year longitudinal examination of cognitive function after hip fracture surgery in non-demented, non-delirious older adults, in order to understand the effect of hip fracture on subsequent cognitive functioning and recovery of this function over time. Our study is unique in hip fracture studies in using a comprehensive neuropsychological battery to capture a broad base of cognitive processes and functions (19). There are two main findings; first, older adults with hip fracture had worse cognitive function post hip fracture that improved over the span of one year relative to healthy comparisons. Second, this post fracture cognitive improvement appeared to be heavily dependent on premorbid education; older adults with higher educational levels showed significant cognitive improvement following a hip fracture while those with lower educational level did not. These findings are important because they support the idea that older adults have the capacity for brain and cognitive resilience after a medical insult such as a hip fracture and surgery, even in advanced old age. We suspect our observation runs counter to a prevailing view of hip fracture as signifying an ineluctable cognitive and functional decline.

In our sample, participants with hip fracture surgery had worse cognitive functioning immediately and at four weeks after the hip fracture, but their RBANS scores increased over the ensuing year representing some degree of cognitive improvement. This most likely represents an initial cognitive insult from the hip fracture and/or surgery, followed by an improvement of some of that cognitive functioning. This is consistent with a study (12) which found that older adults with less premorbid cognitive impairments such as dementia, and less delirium during hospital admission, had cognitive improvement twelve months after hip fracture as evidenced by improvement in their MMSE scores. That study also showed that patients with more cognitive impairment and delirium during hospitalization had rapid decline in cognition one year after hip fracture even after correction for confounding effects. Our study differs in that we used a more comprehensive neurocognitive-screening tool, the RBANS, which is highly sensitive and specific in detecting neurocognitive impairment (19) and minimizes practice effects (18). In addition, we delayed testing until four weeks post baseline when patients were medically stabilized from the fracture and subsequent surgery; and we excluded patients with dementia or delirium.

An alternative explanation for the lower cognitive functioning at week four in our hip fracture sample is pre-existing cognitive impairment; however, this is likely not the sole explanation as there was subsequent improvement in RBANS scores. Also, we cannot rule out “mild” but persistent cases of delirium in our sample, as it is difficult to assess subtle cases of delirium (11). However, our use of the SBT at baseline (week 0) to exclude patients with cognitive impairment should minimize this possibility: milder cases of delirium that eluded our detection at baseline should be unlikely to persist for weeks. Furthermore, while total RBANS scores at week 52 improved amongst the hip fracture patients, they were still lower than the healthy comparisons participants. One explanation could be that people who have a hip fracture tend to be frail and have multiple medical comorbidities.

We also found that participants with higher education levels showed greater cognitive improvement during the year after suffering a hip fracture. This finding is important as it demonstrates that higher educational attainment influences older individuals’ capacity for cognitive reserve and resilience even in the context of advanced old age, frailty, and high medical complexity, as is seen in those with hip fractures. This finding is consistent with several studies that have shown that higher education levels may have a protective effect against neurocognitive decline (29, 30).

One explanation for the improvement we saw after hip fracture might be the scaffolding theory of aging and cognition (STAC) model proposed by (8). According to the STAC model, “compensatory scaffolding” encompasses the use of supplementary neural circuitry and recruitment of regions, such as the prefrontal cortex (31), to maintain and preserve neurocognitive function of the aging brain (7). Any challenge or insult to the aging brain drives compensatory scaffolding to maintain adequate neurocognitive functioning and increases the brain’s resilience (8). Several factors including higher education levels and cardiovascular and physical fitness can lead to enhanced scaffolding so that cognitive function remains high despite neuronal insults and degradation (8, 32). In addition, another study conducted by (33) showed that higher education was associated with lower cortical amyloid beta (Aß) load in the frontal lobe in cognitively normal older adults, indicating that higher levels of education may have a protective effect for Aβ deposition in older age (33). Our findings extend this STAC model by showing its applicability to cognitive improvement after hip fracture (and possibly other medical and operative events) in advanced old age.

In terms of personality traits, our results showed that conscientiousness did not predict improvement in cognition within our hip fracture sample. This is in contrast to findings observed in several studies where conscientiousness was associated with protection from cognitive impairment (26,27). In addition, neither depression scores, ApoE E4, nor BDNF rs6265 status predicted cognitive improvement in our hip fracture sample. Further research should examine the predictors of cognitive improvement after disabling medical events and predictors of brain resilience in this context.

Our study had several limitations; the main one being that we could not assess cognitive function prior to hip fracture, so we cannot know how much cognitive impairment was due to the hip fracture vs. preexisting brain disease. As already discussed, this study is unique in reducing the confounding effect of pre-existing dementia and delirium. The chance for a Type I error given multiple tests is also a limitation.. Lastly, the lack of an IQCODE (34, 35)measure in this study is a limitation; future studies should consider using informant report measures such as the IQCODE or the Everyday Cognition test (ECOG)(36) to rule out pre-existing impairment.

Conclusion:

In our study, non-demented, non-delirious older adults who have sustained hip fractures and surgery have worse cognitive function in the early postoperative period than healthy comparison subjects. However, they have cognitive improvement over the ensuing year, which demonstrates cognitive resilience. More studies are needed to replicate these findings, and to further clarify the brain’s capacity for resilience, even in older age.

Highlights:

This is the first study to examine cognitive function in non demented, non delirious older adults over a span of one year after hip fracture using a comprehensive neuropsychological battery.

Older adults who have sustained hip fracture and surgery had worse cognitive function in the early post operative period than healthy comparisons, however, they had improvement of cognitive function over the span of one year.

Older adults with higher educational levels showed greater cognitive improvement following a hip fracture, while those with lower educational levels did not.

Acknowledgements

This publication was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIMH; R01 MH074596 (EJL) and Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences grant UL1TR000448 (EJL) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Taylor Family Institute for Innovative Psychiatric Research and Center for Brain Research in Mood Disorders (at Washington University) to Dr. Lenze. The funding source(s) had no role in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure

Dr. Lenze has received research support from NIH, FDA, McKnight Brain Research Foundation, Taylor Family Institute for Innovative Psychiatric Research and Center for Brain Research in Mood Disorders (Department of Psychiatry, Washington University), Barnes Jewish Foundation, Janssen, Alkermes, Takeda, and Lundbeck. Professor Miller has received research support from NIH, FDA and PCORI. Dr. Stark has received research support from NIH, CDC, HUD, ACL, Barnes Jewish Foundation, and Toto. Dr. Butters has received research support from the NIH. Dr. Nicol receives or has received research support from the National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH), the Sidney R. Baer, Jr. Foundation, the Center for Brain Research in Mood Disorders at Washington University, and Otsuka America, Inc. for investigator-initiated research studies. She has served as principle or co-investigator on industry-sponsored clinical trials funded by Alkermes, Takeda and Shire.

Dr. Avidan reports no financial conflicts.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Costs of Falls Among Older Adults. August 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/falls/fallcost.html. Accessed February 7, 2018.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hip Fractures Among Older Adults. September 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/falls/adulthipfx.html. Accessed February 7, 2018

- 3.Kannus P, Parkkari J, Sievänen H, Heinonen A, Vuori I & Järvinen M (1996) Epidemiology of hip fractures. Bone, 18, 57S–63S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tolppanen AM, Taipale H, Tanskanen A, Tiihonen J & Hartikainen S (2016) Comparison of predictors of hip fracture and mortality after hip fracture in community-dwellers with and without Alzheimer’s disease - exposure-matched cohort study. BMC Geriatr, 16, 204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stark SL, Roe CM, Grant EA, Hollingsworth H, Benzinger TL, Fagan AM, Buckles VD & Morris JC (2013) Preclinical Alzheimer disease and risk of falls. Neurology, 81, 437–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zuckerman JD (1996) Hip fracture. N Engl J Med, 334, 1519–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dyer SM, Crotty M, Fairhall N, Magaziner J, Beaupre LA, Cameron ID, Sherrington C & F. F. N. F. R. R. S. I. Group (2016) A critical review of the long-term disability outcomes following hip fracture. BMC Geriatr, 16, 158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reuter-Lorenz PA & Park DC (2014) How does it STAC up? Revisiting the scaffolding theory of aging and cognition. Neuropsychol Rev, 24, 355–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruce AJ, Ritchie CW, Blizard R, Lai R & Raven P (2007) The incidence of delirium associated with orthopedic surgery: a meta-analytic review. Int Psychogeriatr, 19, 197–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gruber-Baldini AL, Zimmerman S, Morrison RS, Grattan LM, Hebel JR, Dolan MM, Hawkes W & Magaziner J (2003) Cognitive impairment in hip fracture patients: timing of detection and longitudinal follow-up. J Am Geriatr Soc, 51, 1227–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cole MG, Ciampi A, Belzile E & Zhong L (2009) Persistent delirium in older hospital patients: a systematic review of frequency and prognosis. Age Ageing, 38, 19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beishuizen SJE, van Munster BC, de Jonghe A, Abu-Hanna A, Buurman BM & de Rooij SE (2017) Distinct Cognitive Trajectories in the First Year After Hip Fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc, 65, 1034–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim JM, Kang HJ, Kim JW, Bae KY, Kim SW, Kim JT, Park MS & Cho KH (2017) Associations of Tumor Necrosis Factor-α and Interleukin-1β Levels and Polymorphisms with Post Stroke Depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry, 25, 1300–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diniz BS (2017) Is It All about Inflammation? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry, 25, 1309–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beloosesky Y, Hendel D, Weiss A, Hershkovitz A, Grinblat J, Pirotsky A & Barak V (2007) Cytokines and C-reactive protein production in hip-fracture-operated elderly patients. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 62, 420–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rawson KS, Dixon D, Nowotny P, Ricci WM, Binder EF, Rodebaugh TL, Wendleton L, Doré P & Lenze EJ (2015) Association of functional polymorphisms from brain-derived neurotrophic factor and serotonin-related genes with depressive symptoms after a medical stressor in older adults. PLoS One, 10, e0120685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trzepacz PT, Baker RW & Greenhouse J (1988) A symptom rating scale for delirium. Psychiatry Res, 23, 89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Randolph C, Tierney MC, Mohr E & Chase TN (1998) The Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS): preliminary clinical validity. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol, 20, 310–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duff K, Humphreys Clark JD, O’Bryant SE, Mold JW, Schiffer RB & Sutker PB (2008) Utility of the RBANS in detecting cognitive impairment associated with Alzheimer’s disease: sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive powers. Arch Clin Neuropsychol, 23, 603–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katzman R, Brown T, Fuld P, Peck A, Schechter R & Schimmel H (1983) Validation of a short Orientation-Memory-Concentration Test of cognitive impairment. Am J Psychiatry, 140, 734–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carpenter CR, Bassett ER, Fischer GM, Shirshekan J, Galvin JE & Morris JC (2011) Four sensitive screening tools to detect cognitive dysfunction in geriatric emergency department patients: brief Alzheimer’s Screen, Short Blessed Test, Ottawa 3DY, and the caregiver-completed AD8. Acad Emerg Med, 18, 374–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zuckerman JD, Koval KJ, Aharonoff GB, Hiebert R & Skovron ML (2000) A functional recovery score for elderly hip fracture patients: I. Development. J Orthop Trauma, 14, 20–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Donnellan MB, Oswald FL, Baird BM & Lucas RE (2006) The mini-IPIP scales: tiny-yet-effective measures of the Big Five factors of personality. Psychol Assess, 18, 192–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldberg LR (1999). A broad-bandwidth, public-domain, personality inventory measuring the lower-level facets of several five-factor models In Mervielde I, Deary IJ, De Fruyt F, and Ostendorf F (Eds.), Personality psychology in Europe (Vol. 7, pp. 7–28). Tilburg, The Netherlands: Tilburg University Press [Google Scholar]

- 25.John OP, & Srivastava S (1999). The Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives In Pervin LA & John OP (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (2nd ed., pp. 102–138). New York: Guilford Press [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sutin AR, Stephan Y & Terracciano A (2017) Facets of Conscientiousness and risk of dementia. Psychol Med, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Terracciano A, Iacono D, O’Brien RJ, Troncoso JC, An Y, Sutin AR, Ferrucci L, Zonderman AB & Resnick SM (2013) Personality and resilience to Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology: a prospective autopsy study. Neurobiol Aging, 34, 1045–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. The output/code/data analysis for this paper was generated using SAS software, Version 9.4 of the SAS System for Windows. Copyright © 2002–2003 SAS Institute Inc. SAS and all other SAS Institute Inc. product or service names are registered trademarks or trademarks of SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA.

- 29.Amieva H, Mokri H, Le Goff M, Meillon C, Jacqmin-Gadda H, Foubert-Samier A, Orgogozo JM, Stern Y & Dartigues JF (2014) Compensatory mechanisms in higher-educated subjects with Alzheimer’s disease: a study of 20 years of cognitive decline. Brain, 137, 1167–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bennett DA, Wilson RS, Schneider JA, Evans DA, Mendes de Leon CF, Arnold SE, Barnes LL & Bienias JL (2003) Education modifies the relation of AD pathology to level of cognitive function in older persons. Neurology, 60, 1909–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gutchess AH, Welsh RC, Hedden T, Bangert A, Minear M, Liu LL & Park DC (2005) Aging and the neural correlates of successful picture encoding: frontal activations compensate for decreased medial-temporal activity. J Cogn Neurosci, 17, 84–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barulli D & Stern Y (2013) Efficiency, capacity, compensation, maintenance, plasticity: emerging concepts in cognitive reserve. Trends Cogn Sci, 17, 502–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arenaza-Urquijo EM, Bejanin A, Gonneaud J, Wirth M, La Joie R, Mutlu J, Gaubert M, Landeau B, de la Sayette V, Eustache F & Chételat G (2017) Association between educational attainment and amyloid deposition across the spectrum from normal cognition to dementia: neuroimaging evidence for protection and compensation. Neurobiol Aging, 59, 72–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jorm AF & Korten AE (1988) Assessment of cognitive decline in the elderly by informant interview. Br J Psychiatry, 152, 209–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jorm AF, Scott R, Cullen JS & MacKinnon AJ (1991) Performance of the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE) as a screening test for dementia. Psychol Med, 21, 785–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tomaszewski Farias S, Mungas D, Harvey DJ, Simmons A, Reed BR & Decarli C (2011) The measurement of everyday cognition: development and validation of a short form of the Everyday Cognition scales. Alzheimers Dement, 7, 593–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]