Abstract

A general and enantioselective N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC)-catalyzed lactonization of simple enals and α-ketoesters has been discovered using a new ternary cooperative catalytic system. The highly selective annulation was achieved by using a combination of a chiral NHC, a hydrogen-bond donor, and a metal salt, facilitating self-assembly of the reactive partners. A proposed model for this new mode of NHC chiral relay catalysis is supported by experimental and computational mechanistic studies.

Keywords: N-heterocyclic carbene, NHC, ternary catalysis, lactone, cooperative catalysis, Umpolung, homoenolate

Graphical abstract

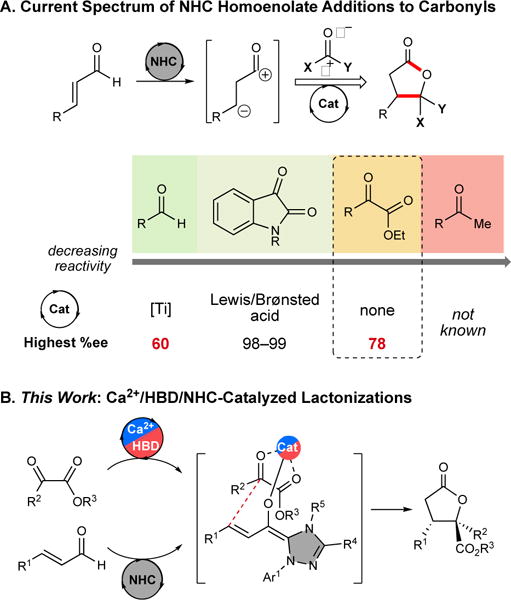

N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC)-catalyzed homoenolate additions are unconventional methods to generate a nucleophilic β-carbon atom for the formation of C–C and C–O bonds.[1] Homoenolate annulations with carbonyl compounds give rise to enantioenriched γ-butyrolactones, which are prevalent structural motifs in natural and bioactive products,[2] as well as direct precursors to substituted tetrahydrofurans,[3] furans,[4] and nucleoside analogues.[5] While isatins,[6] acyl phosphonates,[7] and trifluoromethyl-substituted aryl ketones[8] are selective carbonyl electrophiles with NHC-homoenolate annulations, aryl aldehyde electrophiles[9] afford only moderate annulation yields and enantioselectivities, and simple alkyl ketones are not currently productive substrates (Figure 1A).[1d] The use of α-ketoesters as electrophiles for homoenolate annulations has had only limited success to date.[10] Successful examples of homoenolate additions to carbonyl groups, particularly isatins,[6a-c] have employed an additive or co-catalyst (e.g., Lewis acid (LA), Brønsted acid (BA), or hydrogen bond donor (HBD)) to enhance the enantioselectivity and yield of the reaction (Figure 1A). Cooperative NHC catalysis with compatible Lewis acid or HBD catalysts[11] to activate electrophiles for Umpolung transformations has recently emerged as a powerful strategy to access complex molecular frameworks with high selectivity.[6b, 9, 12] Despite these advances, the use of co-catalysts has not been explored for NHC-catalyzed homoenolate additions to α-ketoesters. We envisioned that under this new type of activation, a co-catalyst could potentially preorganize the α-ketoesters in a fixed geometry, generating a stereodefined ensemble in the enantiodetermining bond formation step (Figure 1B). To this end, we have developed a general and highly enantioselective annulation of enals with α-ketoesters using a novel ternary[13] cooperative chiral NHC/LA/HBD strategy.

Figure 1.

NHC-catalyzed lactonizations.

To test our hypothesis that activation of α-ketoesters using Lewis acids and HBDs may lead to improved annulation enantioselectivities, the effects of several additives were studied alongside NHC precatalysts in the title reaction (Table 1). Inspired by previous cooperatively-catalyzed NHC annulations, conditions using lithium chloride,[3e, 6b] titanium isopropoxide,[9c] scandium triflate,[12e] zinc triflate, magnesium di-tert-butoxide,[12a, 12e] and HBDs as co-catalysts were screened with no improvement to the enantioselectivity (see SI). A variety of magnesium and calcium alkoxides and HBDs were screened as co-catalysts with azolium A, which led to moderate enantioselectivities (32–45% ee, entries 2–3 and SI). The combination of all three catalysts increased the enantioselectivity (entry 4). Notably, while NHC and HBD cooperative systems have been relatively underexplored, the use of calcium complexes in conjunction with NHC catalysis is unreported.

Table 1.

Cooperative catalysis optimizationa

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| entry | NHC | LA | HBD | % yieldb | dr | % eec |

| 1 | A | – | – | 66 | 2:1 | 33/51 |

| 2 | A | Mg(OtBu)2 | – | 64 | 1:1 | 38/45 |

| 3 | A | – | D | 60 | 2:1 | 33/44 |

| 4 | A | Mg(OtBu)2 | D | 67 | 2:1 | 75/38 |

| 5 | A | Mg(OtBu)2 | E | 76 | 3:1 | 41/16 |

| 6 | A | Mg(OtBu)2 | F | 32 | 3:1 | 15/7 |

| 7 | B | Mg(OtBu)2 | D | 80 | 2:1 | 88/94 |

| 8 | C | Mg(OtBu)2 | D | 66 | 2:1 | 4/6 |

| 9 | B | Ca(OMe)2 | D | 75 | 2:1 | 92/91 |

| 10 | B | – | – | quant. | 1:1 | 81/84 |

| 11 | B | Ca(OMe)2 | – | 56 | 1:1 | 46/40 |

| 12 | B | – | D | 15 | 1:1 | 9/6 |

|

| ||||||

| ||||||

Conditions: 1a (0.08 mmol, 1 equiv), 2a (1 equiv), NHC azolium (0.10 equiv), LA (0.15 equiv), HBD (0.15 equiv), DBU (0.15 equiv) in PhMe (0.15 M) at 23 °C for 16 h.

Determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy with trimethoxybenzene as internal standard.

Determined by HPLC analysis.

The optimization of the lactonization was continued by surveying a library of HBDs, NHC catalysts, and bases (Table 1 and SI). Contrary to most HBD-catalyzed transformations, electron-rich aromatic thioureas produced higher enantioselectivities than electron-deficient urea derivatives.[14] The use of sterically congested, electron-rich aromatic thioureas was attempted to improve the diastereoselectivity, but long reaction times and diminished diastereomeric ratios were observed (See SI). A screen of NHC catalysts revealed that triazolium B, first independently reported by Enders and Ye,[15] improved both the yield and %ee of the reaction (entry 7 and SI). When the silyl ether on B was replaced with an alkyl substituent (entry 8 and SI), the observed %ee was significantly diminished, implying that the Lewis basic site on the NHC catalyst may create a key stabilizing interaction (See SI for computational support of the proposed interaction). Employing B with calcium methoxide and HBD D (entry 9) resulted in increased %ee’s for both diastereomeric products compared to lactonizations run with other or in the absence of co-catalysts (entries 7, 9–12). The best %ee and yield was observed using DBU as the base. Importantly, control reactions with no DBU resulted in no observed product, indicating that the metal alkoxide is not acting as a base but that it is more likely involved in organizing the transition state.

After optimization of the reaction conditions, the scope of the lactonization was explored (Table 2). Initially, different ester substituents were investigated (3a–d), and the observed %ee’s (73–94) were higher than those previously reported. Aromatic ortho-, meta-, and para-substituted enals (3e–3k) effectively formed lactones with moderate to high levels of %ee (75–99). While alkyl enals expectedly afforded lower yields (35% of 3l, 57% of 3m),[6b, 9b, 16] they provided lactone products with good %ee’s (up to 87%). Ortho-substituted aromatic α-ketoesters did not react, as reported previously,[10c, 10e] but other aromatic α-ketoesters (3o–3q) gave lactones with moderate to high enantioselectivities (89–98% ee). Although all of the lactonizations proceeded with modest to no diastereoselectivity (3:1–1:1), the products could be separated using column chromatography.

Table 2.

Substrate Scopea

|

To gain a deeper insight into the role of each catalyst in our unique catalytic system, 1H NMR and NOESY 1D spectroscopy and ESI mass spectrometry were used to study the interactions of the electrophile, nucleophile, and additives (Figure 2).[18] The results of the 1H NMR spectroscopy studies showed an unexpected upfield shift (δ 0.12–0.14 ppm) of all of the nucleophile and electrophile protons when each substrate was mixed with the co-catalysts, implying a shielding effect of the aromatic rings of the HBD to the substrates (Figure 2A).[19] The interaction of the aromatic ring of the HBD with the ester was also detected by NOESY 1D experiments, but the signal was diminished when calcium methoxide was added (Figure 2B). This is likely evidence for the binding of calcium between the carbonyls of the α-ketoester.[20] Consistent with this proposed mode of binding, no change by 1H NMR spectroscopy was observed when calcium methoxide and 1,3-diphenylthiourea were mixed alone in toluene-d8, implying that calcium is likely not activating the HBD.[21] ESI mass spectrometry revealed a mass corresponding to the catalyst–substrate complex (NHC B + enal), but no mass corresponding to any co-catalyst adducts.[18b, 22] Observation of this intermediate also suggests that the pendent silyl ether of NHC B remains silylated under the reaction conditions. Due to the heterogeneity of the reaction, kinetic studies to determine the bond order of each catalyst were problematic and DOSY experiments were unsuccessful. Based on the data, we postulate that the combination of catalysts likely forms a network, mimicking the metals and hydrogen bonds present in an enzyme pocket.[14d, 23]

Figure 2. NMR Studies of the Lactonization.

(A) 1H NMR spectra (CDCl3) of solutions of (1) catalyst D, (2) α-ketoester 2c, (3) 2c + D + Ca(OMe)2, (4) enal 1l, and (5) 1l + D + Ca(OMe)2. (B) NOESY 1D spectra of solutions of (2) α-ketoester 2c + D and (3) 2c + D + Ca(OMe)2.

We next sought to enhance our model for enantioinduction in the lactonization. Experiments with modified HBDs were performed to investigate the interactions of N–H bonds and aryl substituents with the other reaction partners (Figure 3A). Parameters of the transition state that we investigated were (1) π-stacking (G), (2) conformation of the thiourea (H, I),[24] and (3) bridging of the nucleophile and electrophile (H, I).[25] Each modification of the optimal HBD D resulted in decreased selectivity, leading us to hypothesize that the H-bonding ability of the donor N–H bonds and π-stacking of the Z,Z-1,3-diphenylthiourea HBD may play crucial roles in the selectivity (see below for integrated DFT analysis).

Figure 3.

(A) Mechanistic studies through modifications of the HBD catalyst. (B) Computed stereodetermining TSs with catalyst B, HBD D, and Ca(OMe)2 (Table 1, Entry 9). adr was determined by unpurified 1H NMR spectroscopy, and %ee was determined by HPLC analysis. NHC catalyst highlighted in green. Light green lines indicate electrostatic interactions and dashed lines show coordination to the Ca2+ ion. Distances are in Å and energies (ΔΔG‡) in kcal/mol.

DFT computations provided further insight into the complexation motif that may be operative in the stereodetermining C–C bond-forming transition structures (TSs). The TSs leading to the major (TS-(Re,Re)-Major) and minor (TS-(Si,Si)-Minor) enantiomers of the lactone products are shown in Figure 3B. Geometry optimizations were completed using PBE/6-31G*[26] with the energy of solvation modeled in toluene with PBE[27]/6-311+G**/SMD.[28] Dispersion corrections were also completed using the PBE D3BJ model.[29] The computed energies were further refined using PBE/6-311++G(2df,p). The computed enantioselectivity of 1.7 kcal/mol (90% ee) is in excellent agreement with experiment (1.8 kcal/mol, 92% ee, Table 1, Entry 9). Both TSs feature a Ca2+ ion chelated to the carbonyl groups of the α-ketoester electrophile and the oxygen atom of the anionic homoenolate nucleophile. The methoxide counterion binds to Ca2+, forming a distorted tetrahedral metal center. The negative charge of the methoxide ion is further stabilized by H-bonding with the thiourea N–H groups. This binding mode corroborates the LCMS results in which the thiourea preferentially binds to methoxide rather than the substrate (See SI). Thiourea HBDs are known to interact with halides,[30] but are less frequently reported with alkoxides.[31] The formation of the thiourea–methoxide complex is critical to induce the high enantioselectivity of the reaction. The thiourea acts as a relay auxiliary, with the phenyl groups transferring the chiral information of the catalyst to the distal reactive center.[32] In TS-(Re,Re)-Major, the HBD phenyl group engages in a C–H–π interaction,[33] which is strengthened by the developing positive charge of the catalyst. This interaction is absent in the minor TS shown in Figure 3B, due to the catalyst NMes group and the pendent stereodirecting group blocking the planar azolium. Removing the HBD aryl groups (Figure 3A, G) eliminates the favored C–H–π interaction in TS-(Re,Re)-Major and decreases the selectivity. Methylating the thiourea (H) reduces the selectivity by disfavoring complexation to methoxide, thus interfering with the formation of the chiral relay ion complex. Full methylation (I) completely eliminates the ability of the HBD to form the complex, and correspondingly low selectivity was observed (49% ee) in comparison to the reaction run with no HBD present (46% ee, Table 1, entry 11).

In conclusion, an efficient asymmetric lactonization of unsaturated aldehydes with α-ketoesters using NHC/Ca2+/HBD cooperative catalysis has been developed. Enals can be transformed into the corresponding enantiomerically enriched substituted γ-butyrolactones in high yield and enantioselectivity. This solution to a challenging reaction employs a new mode of cooperative catalysis. In harnessing an ensemble effect of three distinct entities with low entropic penalties, this new mode of NHC catalysis moves the efficiency of organocatalysis closer to nature’s catalysis. This process broadens the scope of NHC cooperative catalysis that address less reactive substrate classes and should find applications in complex synthesis.

Experimental Section

General Procedure for the Synthesis of Lactones

In a nitrogen filled dry box, a screw-capped 1 dram vial equipped with a magnetic stirbar was charged with an α-ketoester (1 equiv), triazolium precatalyst B (10 mol %), HBD D (15 mol %), and Ca(OMe)2 (15 mol %). Aldehydes (1 equiv) that are solid were also added to this same vial in the dry box. The vial was capped with a septum cap, removed from the dry box, and fitted with an argon balloon. The heterogeneous mixture was then diluted with PhMe (0.15 M), and to this mixture was added aldehyde (1 equiv), followed by DBU (15 mol %) via syringe. The reaction mixture was stirred at 23 °C for 12–16 h. After complete conversion of the aldehyde as determined by TLC, the reaction mixture was concentrated in vacuo, loaded directly onto a column of silica gel, and the crude products were isolated by flash column chromatography (2–10 % EtOAc/hexanes, UV and ceric ammonium nitrate stain visualization).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank NIGMS (GM073072) for financial support of this work. PHYC is the Vicki & Patrick F. Stone Scholar of Oregon State University and gratefully acknowledges financial support from the Stone Family and the NSF (CHE-1352663). DMW also acknowledges financial support from the Johnson Research Fellowship.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/adsc.201######.

References

- 1.For recent NHC reviews, see:; a) Nair V, Menon RS, Biju AT, Sinu CR, Paul RR, Jose A, Sreekumar V. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:5336–5346. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15139h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Bugaut X, Glorius F. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:3511–3522. doi: 10.1039/c2cs15333e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Hopkinson MN, Richter C, Schedler M, Glorius F. Nature. 2014;510:485–496. doi: 10.1038/nature13384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Menon RS, Biju AT, Nair V. Chem Soc Rev. 2015;44:5040–5052. doi: 10.1039/c5cs00162e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Flanigan DM, Romanov-Michailidis F, White NA, Rovis T. Chem Rev. 2015;115:9307–9387. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.For manipulations of γ-butyrolactones and their appearance in natural or bioactive products, see:; a) S’kof M, Svete J, Kmetič M, Golič-Grdadolnik S, Stanovnik B. Eur J Org Chem. 1999:1581–1584. [Google Scholar]; b) Pirc S, Rečnik S, Škof M, Svete J, Golič L, Meden A, Stanovnik B. J Heterocyclic Chem. 2002;39:411–416. [Google Scholar]; c) Miranda PO, Estévez F, Quintana J, García CI, Brouard I, Padrón JI, Pivel JP, Bermejo J. J Med Chem. 2004;47:292–295. doi: 10.1021/jm034216y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Chimenti F, Cottiglia F, Bonsignore L, Casu L, Casu M, Floris C, Secci D, Bolasco A, Chimenti P, Granese A, Befani O, Turini P, Alcaro S, Ortuso F, Trombetta G, Loizzo A, Guarino I. J Nat Prod. 2006;69:945–949. doi: 10.1021/np060015w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Xu HC, Brandt JD, Moeller KD. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:3868–3871. [Google Scholar]; f) Nickerson LA, Huynh V, Balmond EI, Cramer SP, Shaw JT. J Org Chem. 2016;81:11404–11408. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.6b01997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Suh H, Wilcox CS. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:470–481. [Google Scholar]; b) Reissig HU, Holzinger H, Glomsda G. Tetrahedron. 1989;45:3139–3150. [Google Scholar]; c) Murata Y, Kamino T, Aoki T, Hosokawa S, Kobayashi S. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:3175–3177. doi: 10.1002/anie.200454212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Zhu Y, Zhai C, Yang L, Hu W. Chem Commun. 2010;46:2865–2867. doi: 10.1039/b924845e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Lee A, Scheidt KA. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:7594–7598. doi: 10.1002/anie.201403446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dean FM. In: Adv Heterocycl Chem. Katritzky AR, editor. Vol. 30. Academic Press; 1982. pp. 167–238. [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Jõgi A, Ilves M, Paju A, Pehk T, Kailas T, Müürisepp A-M, Lopp M. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2008;19:628–634. [Google Scholar]; b) Nakatsuji H, Sawamura Y, Sakakura A, Ishihara K. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:6974–6977. doi: 10.1002/anie.201400946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Sun LH, Shen LT, Ye S. Chem Commun. 2011;47:10136–10138. doi: 10.1039/c1cc13860j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Dugal-Tessier J, O’Bryan EA, Schroeder TBH, Cohen DT, Scheidt KA. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:4963–4967. doi: 10.1002/anie.201201643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Li JL, Sahoo B, Daniliuc CG, Glorius F. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:10515–10519. doi: 10.1002/anie.201405178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Lin Y, Yang L, Deng Y, Zhong G. Chem Commun. 2015;51:8330–8333. doi: 10.1039/c5cc02096d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jang KP, Hutson GE, Johnston RC, McCusker EO, Cheong PHY, Scheidt KA. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:76–79. doi: 10.1021/ja410932t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.a) Matsuoka Y, Ishida Y, Sasaki D, Saigo K. Chem Eur J. 2008;14:9215–9222. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Fu Z, Xu J, Zhu T, Leong WWY, Chi YR. Nat Chem. 2013;5:835–839. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a) Burstein C, Glorius F. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:6205–6208. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Sohn SS, Rosen EL, Bode JW. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:14370–14371. doi: 10.1021/ja044714b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Cardinal-David B, Raup DEA, Scheidt KA. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:5345–5347. doi: 10.1021/ja910666n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Cohen DT, Scheidt KA. Chem Sci. 2012;3:53–57. doi: 10.1039/C1SC00621E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.a) Burstein C, Tschan S, Xie X, Glorius F. Synthesis. 2006:2418–2439. [Google Scholar]; b) Tewes F, Schlecker A, Harms K, Glorius F. J Organomet Chem. 2007;692:4593–4602. [Google Scholar]; c) Li Y, Zhao ZA, He H, You SL. Adv Synth Catal. 2008;350:1885–1890. [Google Scholar]; d) Check CT, Jang KP, Schwamb CB, Wong AS, Wang MH, Scheidt KA. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54:4264–4268. doi: 10.1002/anie.201410118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For less general but selective variants, see:; e) Goodman CG, Walker MM, Johnson JS. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:122–125. doi: 10.1021/ja511701j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Jin Z, Jiang K, Fu Z, Torres J, Zheng P, Yang S, Song BA, Chi YR. Chem Eur J. 2015;21:9360–9363. doi: 10.1002/chem.201501481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.For select reviews on cooperative catalysis, see:; a) Shao Z, Zhang H. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38:2745–2755. doi: 10.1039/b901258n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Allen AE, MacMillan DWC. Chem Sci. 2012;3:633–658. doi: 10.1039/C2SC00907B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For a recent example of cooperative catalysis, see:; (c) Shimoda Y, Yamamoto H. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:6855–6858. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b03592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.For relevant select examples of NHC cooperative catalysis, see:; a) Raup DEA, Cardinal-David B, Holte D, Scheidt KA. Nat Chem. 2010;2:766–771. doi: 10.1038/nchem.727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Brand JP, Siles JIO, Waser J. Synlett. 2010:881–884. [Google Scholar]; c) Hirano K, Piel I, Glorius F. Chem Lett. 2011;40:786–791. [Google Scholar]; d) DiRocco DA, Rovis T. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:8094–8097. doi: 10.1021/ja3030164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Mo J, Chen X, Chi YR. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:8810–8813. doi: 10.1021/ja303618z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Nawaz F, Zaghouani M, Bonne D, Chuzel O, Rodriguez J, Coquerel Y. Eur J Org Chem. 2013:8253–8264. [Google Scholar]; g) Jin Z, Xu J, Yang S, Song BA, Chi YR. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:12354–12358. doi: 10.1002/anie.201305023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Du Z, Shao Z. Chem Soc Rev. 2013;42:1337–1378. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35258c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Youn SW, Song HS, Park JH. Org Lett. 2014;16:1028–1031. doi: 10.1021/ol5000617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j) Namitharan K, Zhu T, Cheng J, Zheng P, Li X, Yang S, Song BA, Chi YR. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3982. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k) Wang MH, Cohen DT, Schwamb CB, Mishra RK, Scheidt KA. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:5891–5894. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b02887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; l) Wang MH, Scheidt KA. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;55:14912–14922. doi: 10.1002/anie.201605319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.For recent ternary or synergistic catalysis systems, see:; a) Xiang Y, Barbosa R, Li X, Kruse N. ACS Catalysis. 2015;5:2929–2934. [Google Scholar]; b) Shaw MH, Shurtleff VW, Terrett JA, Cuthbertson JD, MacMillan DWC. Science. 2016;352:1304–1308. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf6635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Kato S, Saga Y, Kojima M, Fuse H, Matsunaga S, Fukatsu A, Kondo M, Masaoka S, Kanai M. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:2204–2207. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b00253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Yang Q, Zhang L, Ye C, Luo S, Wu LZ, Tung CH. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2017;56:3694–3698. doi: 10.1002/anie.201700572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.For reviews and pertinent studies of HBDs, see:; a) Auvil TJ, Schafer AG, Mattson AE. Eur J Org Chem. 2014:2633–2646. [Google Scholar]; b) Okino T, Hoashi Y, Takemoto Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:12672–12673. doi: 10.1021/ja036972z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Wittkopp A, Schreiner PR. Chem Eur J. 2003;9:407–414. doi: 10.1002/chem.200390042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Taylor MS, Jacobsen EN. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:1520–1543. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.a) Enders D, Han J. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2008;19:1367–1371. [Google Scholar]; b) Zhang YR, He L, Wu X, Shao PL, Ye S. Org Lett. 2008;10:277–280. doi: 10.1021/ol702759b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Huang XL, He L, Shao PL, Ye S. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:192–195. doi: 10.1002/anie.200804487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Z, Yu X, Wu J. Chem Commun. 2010;46:6356–6358. doi: 10.1039/c0cc01207f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.CCDC 1548340 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for 3k. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

- 18.For relevant mechanistic studies of catalytic systems and characterization, see:; a) Lippert KM, Hof K, Gerbig D, Ley D, Hausmann H, Guenther S, Schreiner PR. Eur J Org Chem. 2012:5919–5927. [Google Scholar]; b) Bastida D, Liu Y, Tian X, Escudero-Adán E, Melchiorre P. Org Lett. 2013;15:220–223. doi: 10.1021/ol303312p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Noda H, Furutachi M, Asada Y, Shibasaki M, Kumagai N. Nat Chem. 2017;9:571–577. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Su H, Huang W, Yang Z, Lin H, Lin H. J Incl Phenom Macrocycl Chem. 2012;72:221–225. [Google Scholar]

- 20.For select examples of calcium ions activating carbonyls, see:; a) Robl C, Weiss A. Mater Res Bull. 1987;22:373–380. [Google Scholar]; b) Tsubogo T, Yamashita Y, Kobayashi S. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:9117–9120. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Abrahams BF, Grannas MJ, Hudson TA, Hughes SA, Pranoto NH, Robson R. Dalton T. 2011;40:12242–12247. doi: 10.1039/c1dt10962f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.For LA activation of HBDs, see:; a) So SS, Burkett JA, Mattson AE. Org Lett. 2011;13:716–719. doi: 10.1021/ol102899y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Marqués-López E, Alcaine A, Tejero T, Herrera RP. Eur J Org Chem. 2011:3700–3705. doi: 10.1039/c0ob01059f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.For relevant NHC mechanistic studies, see:; a) Schrader W, Handayani PP, Burstein C, Glorius F. Chem Commun. 2007:716–718. doi: 10.1039/b613862d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Corilo YE, Nachtigall FM, Abdelnur PV, Ebeling G, Dupont J, Eberlin MN. RSC Advances. 2011;1:73–78. [Google Scholar]; c) Bortolini O, Chiappe C, Fogagnolo M, Giovannini PP, Massi A, Pomelli CS, Ragno D. Chem Commun. 2014;50:2008–2011. doi: 10.1039/c3cc48929a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.For studies on metals in enzymes, see:; Sträter N, Lipscomb WN, Klabunde T, Krebs B. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1996;35:2024–2055. [Google Scholar]

- 24.For HBD properties and reactivities, see:; a) Bryantsev VS, Hay BP. J Phys Chem A. 2006;110:4678–4688. doi: 10.1021/jp056906e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Clayden J, Hennecke U, Vincent MA, Hillier IH, Helliwell M. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2010;12:15056–15064. doi: 10.1039/c0cp00571a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Jakab G, Tancon C, Zhang Z, Lippert KM, Schreiner PR. Org Lett. 2012;14:1724–1727. doi: 10.1021/ol300307c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Madarász Á, Dósa Z, Varga S, Soós T, Csámpai A, Pápai I. ACS Catal. 2016;6:4379–4387. [Google Scholar]

- 25.For anionic thiourea intereactions, see:; Lin B, Waymouth RM. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:1645–1652. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b11864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frisch MJ, et al. Gaussian 09. Gaussian, Inc.; Wallingford, CT: 2009. [Google Scholar]; See SI for full citation.

- 27.Perdew JP, Burke K, Ernzerhof M. Phys Rev Lett. 1996;77:3865–3868. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marenich AV, Cramer CJ, Truhlar DG. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113:6378–6396. doi: 10.1021/jp810292n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grimme S, Ehrlich S, Goerigk L. J Comput Chem. 2011;32:1456–1465. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.For select examples of HBD-halide interactions, see:; a) Kennedy CR, Lehnherr D, Rajapaksa NS, Ford DD, Park Y, Jacobsen EN. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:13525. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b09205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Doyle AG, Jacobsen EN. Chem Rev. 2007;107:5713–5743. doi: 10.1021/cr068373r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.For a different HBD-alkoxide interaction, see:; Zhang X, Jones GO, Hedrick JL, Waymouth RM. Nat Chem. 2016;8:1047–1053. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Corminboeuf O, Quaranta L, Renaud P, Liu M, Jasperse CP, Sibi MP. Chem Eur J. 2003;9:28–35. doi: 10.1002/chem.200390000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wheeler SE, Bloom JWG. J Phys Chem A. 2014;118:6133–6147. doi: 10.1021/jp504415p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.