Abstract

Aims

Sex differences in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) remain unclear. We sought to characterize sex differences in a large HCM referral centre population.

Methods and results

Three thousand six hundred and seventy-three adult patients with HCM underwent evaluation between January 1975 and September 2012 with 1661 (45.2%) female. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were assessed via log-rank test. Cox proportional hazard regression analyses evaluated the relation of sex with survival. At index visit, women were older (59 ± 16 vs. 52 ± 15 years, P < 0.0001) had more symptoms [New York Heart Association (NYHA) Class III–IV 45.0% vs. 35.3%, P < 0.0001], more obstructive physiology (77.4% vs. 71.8%, P = 0.0001), more mitral regurgitation (moderate or greater in 56.1% vs. 43.9%, P < 0.0001), higher E/e′ ratio (n = 1649, 20.6 vs. 15.6, P < 0.0001), higher estimated pulmonary artery systolic pressure (n = 1783, 40.8 ± 15.4 vs. 34.8 ± 10.8 mmHg, P < 0.0001), worse cardiopulmonary exercise performance (n = 1267; percent VO2 predicted 62.8 ± 20% vs. 65.8 ± 19.2%, P = 0.007), and underwent more frequent alcohol septal ablation (4.9% vs. 3.0%, P = 0.004) but similar frequency of myectomy (28% vs. 30%, P = 0.24). Median follow-up was 10.9 (IQR 7.4–16.2) years. Kaplan–Meier analysis demonstrated lower survival in women compared with men (P < 0.0001). In multivariable modelling, female sex remained independently associated with mortality (HR 1.13 [1.03–1.22], P = 0.01) when adjusted for age, NYHA Class III–IV symptoms, and cardiovascular comorbidities.

Conclusion

Women with HCM present at more advanced age, with more symptoms, worse cardiopulmonary exercise tolerance, and different haemodynamics than men. Sex is an important determinant in HCM management as women with HCM have worse survival. Women may require more aggressive diagnostic and therapeutic approaches.

Keywords: Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, Female, Male, Sex, Gender

Introduction

Patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) are characterized by inherited cardiac hypertrophy, as opposed to hypertrophy secondary to another pathologic process.1–3 On an organ level, there is diversity in the extent of myocardial hypertrophy, amount of left ventricular (LV) outflow tract obstruction and degree of diastolic dysfunction. The large phenotypic spectrum accounts for differences in clinical course including asymptomatic with normal lifespan, sudden cardiac death (SCD), and medically refractory heart failure symptoms requiring septal reduction therapy.

Key differences between men and women have been explored in a variety of cardiac conditions spanning heart failure, valvular heart disease, coronary artery disease, dilated cardiomyopathy, and others.4–17 Sex differences in HCM are less well understood. While there have been studies describing demographic and clinical differences in HCM based upon sex, data assessing survival are limited and previously have shown no differences.18,19 However, it is important to clarify sex differences in survival outcomes in order to better address diagnostic and treatment strategies for patients with this condition. We hypothesized that study of a large population of patients with HCM would demonstrate clinical and haemodynamic differences between men and women, and that these differences would affect survival. Therefore, we sought to characterize sex differences in symptoms, phenotypes, treatments, and outcomes in a large, single-centre HCM referral population.

Methods

Patient selection

The studied population comprised adult patients with HCM who underwent index evaluation at Mayo Clinic (Rochester, MN, USA) between January 1975 and September 2012. The diagnosis of HCM was determined both clinically and by echocardiography, on the basis of the presence of myocardial hypertrophy in the absence of local or systemic oetiologies.1,20,21 Informed consent was obtained for use of patient medical records for research purposes in accordance with Minnesota law and an Institutional Review Board approved study.

The diagnosis of atrial fibrillation (AF) was based on a prior history of paroxysmal or chronic AF or demonstration of AF on index electrocardiogram. It was noted if patients had a history of systemic hypertension, although clinical evaluation in all cases determined that hypertension did not obviate the diagnosis of HCM. Survival data were collected from the electronic health records and the national death and location database (Accurint, Lexisnexis for Mayo Clinic patients). Assuming no lag in data, a date of last follow-up of January 2017 was used as the last follow-up in those patients still assumed to be alive. Plasma B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) assessed via fluorescence immunoassay (Biosite Diagnostics, San Diego, CA, USA)22 and plasma N-terminal pro BNP (NT-Pro BNP) measured with electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA)23 were obtained when clinically indicated. Symptom-limited graded exercise testing was performed using an institutionally designed incremental exercise testing protocol as described previously.24,25 Continuous electrocardiographic monitoring (Marquette Electronics, Milwaukee, WI, USA) and breath-to-breath metabolic measurement (Medical Graphics, St. Paul, MN, USA) were utilized as previously described.26

Echocardiographic evaluation

The presence of a transthoracic echocardiographic examination constituted an inclusion criterion. Left ventricular cavity size, LV mass, wall thickness, and ejection fraction were determined in standard fashion.27 Left atrial volume index was calculated by either the prolate ellipse or biplane area-length methods,28 with left atrial enlargement defined as a left atrial volume index ≥34 cm3/m2. Mitral regurgitation was graded as none to mild, moderate, moderately severe or severe after analysing jet area and width, spectral Doppler intensity, as well as regurgitation quantitation with the continuity equation and/or PISA method as appropriate.29 Not all mitral regurgitation could be quantitated given jet eccentricity and LV outflow tract flow turbulence merging with the regurgitant jet flow convergence. Mitral inflow velocity curves [peak early diastolic velocity (E) and peak late diastolic velocity (A)] and annular tissue Doppler signals (medial e′ and lateral e′) were obtained as previously described.30 Right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP) was estimated in a standard fashion per ASE guidelines.31 Right ventricular systolic pressure cutoffs of 35 and 50 mmHg for assessment of pulmonary hypertension (PH) were assessed, as previously.32 LV outflow tract gradients were obtained by continuous-wave Doppler interrogation of the LV outflow tract from an apical window and calculated using the modified Bernoulli equation (i.e. gradient = 4vLVOT2, where vLVOT is peak LV outflow tract velocity). Resting obstruction was defined as a LV outflow tract gradient of ≥30 mmHg. The presence of labile obstruction (provoked gradient ≥50 mmHg) was determined by provocative manoeuvres (Valsalva manoeuvre, amyl nitrite inhalation, and exercise). Because of the long timespan of this study, some patients were evaluated prior to the availability of certain echocardiographic parameters (mainly Doppler-based), which were unavailable for incorporation in this analysis.

Data analysis

Normality of distribution was determined via histogram visual assessment. Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation ( SD) when normally distributed; non-normally distributed variables are reported as median with IQR. Comparison of sex differences in variables were performed using Student’s t-tests, Fischer exact tests, and Wilcoxon rank sum tests as appropriate. All-cause mortality was the endpoint of interest in this analysis. Survival was assessed using Kaplan–Meier survival curves, with log rank test P-values reported. Survival was also compared with expected survival determined via an age- and sex-matched population derived from US Census data.

Univariate and multivariable Cox proportional hazard regression analyses were performed to determine the relation of sex with study endpoints, with hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) reported. To assess for the influence of date of referral on survival, visit date was added to the multivariable model and assessed as both a linear and non-linear variable. Logistic regression analysis was used to construct a propensity score, which was used as an adjustment variable in the overall survival models. Using sex as the x variable in the model, additional clinical variables were included. The score from this model was used as a potential adjusting variable in the multivariable Cox proportional hazards model with sex.

Any missing data were handled by omission from the respective analyses. Statistical significance was set a priori at P < 0.05. All analyses were performed using JMP version 9.0.2 and SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Study population

A total of 3673 patients were included in the study, with male predominance [2012 men (55%), P < 0.0001 compared with the expected sex distribution of 50% given an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern]. Eight hundred and sixty-eight (23.6%) patients underwent index evaluation at our institution before 1990, 936 (25.5%) patients in the period 1990 to 2000, and 1869 (50.9%) patients after 2000. The average age was 55 ± 16 years. Patient demographics are shown in Table 1. This was primarily a referral population since only 197 of 3673 (5.4%) patients resided in Olmsted County or one of the nearby counties with 559XX zip codes (Mower, Steele, Houston, and Dodge). Reflecting the referral composition of our practice, 40% of patients presented with New York Heart Association (NYHA) Class III–IV symptoms. Compared with men, women were older at index evaluation (59 ± 16 vs. 52 ± 15 years, P < 0.0001), more likely to carry a prior diagnosis of systemic hypertension (49.1% vs. 43.4%, P = 0.0010), and were more symptomatic (NYHA Class III–IV symptoms in 45.0% vs. 35.3%, P < 0.0001). When assessed by age quartiles, systemic hypertension was more common in men in the first age quartile (P = 0.002) and women in the last quartile (P = 0.01). There were no age-dependent trends in other comorbidities across age quartiles. Women were more likely to present NYHA Class III–IV symptoms across all age quartiles (P ≤ 0.01 for all). Women were slightly less likely to be taking beta receptor antagonists but were more likely to be utilizing calcium channel antagonists (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Variables | Women n = 1661 (45%) | Men n = 2012 (55%) | P-value | All patients n = 3673 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 59 ± 16 | 52 ± 15 | <0.0001 | 55 ± 16 |

| Referral patient, n (%) | 1560 (94) | 1916 (95) | 0.09 | 3476 (95) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 123 ± 21 | 124 ± 17 | 0.40 | 123 ± 19 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 70 ± 11 | 73 ± 11 | <0.0001 | 72 ± 11 |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 68 ± 13 | 64 ± 12 | <0.0001 | 66 ± 12 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 28.3 ± 6.7 | 28.9 ± 5.0 | 0.0053 | 28.6 ± 5.8 |

| Body surface area (m2) | 1.78 ± 0.21 | 2.10 ± 0.21 | <0.0001 | 1.95 ± 0.26 |

| NYHA Class III–IV, n (%) | 748 (45) | 710 (35) | <0.0001 | 1458 (40) |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 271 (16) | 336 (17) | 0.89 | 607 (17) |

| Systemic hypertension, n (%) | 816 (49) | 874 (43) | 0.0010 | 1690 (46) |

| Syncope, n (%) | 236 (14) | 309 (15) | 0.24 | 545 (15) |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 283 (17) | 367 (18) | 0.36 | 650 (18) |

| Non-sustained ventricular tachycardia, n (%)a | 41 (21) | 74 (25) | 0.33 | 115 (23) |

| ICD, n (%) | 99 (6) | 149 (7) | 0.086 | 248 (7) |

| Resuscitated SCD, n (%) | 7 (0.4) | 10 (0.5) | 0.63 | 17 (0.5) |

| Family history of HCM, n (%) | 392 (24) | 422 (21) | 0.085 | 814 (22) |

| Family history of SCD, n (%) | 242 (15) | 302 (15) | 0.64 | 544 (15) |

| BNP (pg/mL)b | 250 (IQR 115–526) | 126 (IQR 50–304) | <0.0001 | 173 (IQR 71–383) |

| NT-Pro BNP (pg/mL)c | 1022 (IQR 372–1796) | 476 (IQR 237–994) | <0.0001 | 649 (IQR 276–1340) |

| VO2 (mL/kg/min)d | 16.8 ± 5.2 | 22.2 ± 6.7 | <0.0001 | 20.1 ± 6.7 |

| Percentage VO2 predicted (%)d | 63 ± 20 | 66 ± 19 | 0.0073 | 65 ± 20 |

| Medications, n (%) | ||||

| Beta receptor antagonist | 1088 (66) | 1370 (68) | 0.042 | 2458 (67) |

| Calcium channel blocker | 664 (40) | 706 (35) | 0.0031 | 1370 (37) |

| ACE-inhibitor/ARB | 169 (10) | 251 (12) | 0.76 | 420 (11) |

| Disopyramide | 146 (9) | 156 (8) | 0.27 | 302 (8) |

| Amiodarone | 90 (5) | 104 (5) | 0.77 | 194 (5) |

| Future alcohol septal ablation | 81 (5) | 61 (3) | 0.0044 | 142 (4) |

| Future septal myectomy | 497 (30) | 566 (28) | 0.24 | 1063 (29) |

| Future septal reduction therapy | 572 (34) | 619 (31) | 0.02 | 1191 (32) |

Continuous variables expressed as mean ± SD or median and IQR.

ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; ICD, internal cardiac defibrillator; NT-Pro BNP, Amino-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide; SCD, sudden cardiac death; NYHA, New York Heart Association; IQR, Interquartile range; SD, standard deviation.

Holter data available in n = 491 (13%).

BNP assessed in n = 763 (21%).

NT-Pro BNP assessed in n = 294 (8%).

Cardiopulmonary exercise testing performed in n = 1267 (35%).

Natriuretic peptide assessment was performed in a minority of patients (29%). Plasma B-type natriuretic peptide was higher in women compared with men [n = 763, 250 (IQR 115–526) vs. 126 (IQR 50–304) pg/mL, P < 0.0001] as was NT-Pro BNP [n = 294, 1022 (IQR 372–1796) vs. 476 (IQR 237–994) pg/mL, P < 0.0001]. It should be acknowledged, however, that BNP and NT-pro BNP tend to be higher in women and with increasing age, even in the absence of cardiac disease.22,33 In patients with clinically driven cardiopulmonary exercise testing, women had worse exercise capacity, both with regards to VO2 (n = 1267, 16.8 ± 5.2 vs. 22.2 ± 6.7 mL/kg/min, P < 0.0001) and percent VO2 predicted (63 ± 20 vs. 66 ± 19%, P = 0.0031). Men were more likely to undergo cardiopulmonary exercise assessment compared with women (40.5% vs. 31.7%, P < 0.0001).

Echocardiographic assessment

Index echocardiographic evaluation is shown in Table 2. The median LV outflow tract gradient at rest was 29 (IQR 8–70) mmHg. There was evidence of resting obstruction in 1830 patients (50%), with an additional 900 patients (25%) demonstrating labile obstruction. Women had a higher LV outflow tract gradient when compared with men [36 (IQR 10–81) vs. 23 (IQR 0–61) mmHg] and were more likely to demonstrate resting obstruction when compared with men (54% vs. 46%, P < 0.0001). Consistent with these results, women had more mitral regurgitation (moderate or greater in 28% vs. 18%, P < 0.0001).

Table 2.

Pre-septal reduction echocardiographic characteristics

| Variables | Women n = 1661 (45%) | Men n = 2012 (55%) | P-value | All patients n = 3673 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LV outflow tract gradient (mmHg) | 36 (IQR 10–81) | 23 (IQR 0–61) | <0.0001 | 29 (IQR 8–70) |

| Resting obstruction, n (%) | 905 (54) | 925 (46) | <0.0001 | 1830 (50) |

| Labile obstruction, n (%) | 380 (23) | 520 (26) | 0.038 | 900 (25) |

| Non-obstructive, n (%) | 376 (23) | 567 (28) | 0.0001 | 943 (25) |

| LV ejection fraction (%) | 71 ± 8 | 69 ± 9 | <0.0001 | 70 ± 9 |

| LV end diastolic dimension (mm) | 43 ± 6 | 47 ± 6 | <0.0001 | 45 ± 6 |

| Anteroseptal wall thickness (mm) | 17.8 ± 5.5 | 18.3 ± 5.5 | 0.016 | 18 ± 6 |

| Wall thickness >30 mm, n (%) | 41 (2) | 50 (2) | 0.83 | 91 (2) |

| Posterior wall thickness (mm) | 12.6 ± 3.1 | 13.2 ± 3.1 | <0.0001 | 13 ± 3 |

| LV mass (g) | 265 ± 101 | 319 ± 110 | <0.0001 | 295 ± 109 |

| LV mass index (g/m2) | 150 ± 57 | 152 ± 51 | 0.16 | 151 ± 54 |

| Moderate or greater mitral regurgitation, n (%)a | 329 (28) | 257 (18) | <0.0001 | 586 (22) |

| Mitral E velocity (cm/s)b | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 0.8 ± 0.3 | <0.0001 | 0.9 ± 0.3 |

| Mitral A velocity (cm/s)b | 0.9 ± 0.4 | 0.7 ± 0.3 | <0.0001 | 0.8 ± 0.3 |

| E/A ratiob | 1.2 ± 0.8 | 1.4 ± 0.7 | 0.0002 | 1.3 ± 0.7 |

| Medial e’ (cm/s)c | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 0.06 ± 0.02 | <0.0001 | 0.05 ± 0.02 |

| Lateral e’ (cm/s)c | 0.06 ± 0.03 | 0.07 ± 0.03 | <0.0001 | 0.07 ± 0.03 |

| Medial E/e’ ratioc | 21 ± 10 | 16 ± 7 | <0.0001 | 17.7 ± 8.4 |

| Lateral E/e’ ratioc | 16 ± 8 | 12 ± 6 | <0.0001 | 13.9 ± 7.3 |

| Left atrial volume index (cm3/m2)d | 48 ± 18 | 49 ± 25 | 0.23 | 48 ± 23 |

| Left atrial enlargement, n (%)d | 537 (76) | 733 (73) | 0.18 | 1270 (75) |

| Estimated RVSP (mmHg)e | 36 (IQR 30–48) | 32 (IQR 28–39) | <0.0001 | 34 (IQR 28–43) |

| RVSP ≥35 mmHg, n (%)e | 472 (56) | 364 (39) | <0.0001 | 836 (47) |

| RVSP ≥50 mmHg, n (%)e | 175 (21) | 87 (9) | <0.0001 | 262 (15) |

Continuous variables expressed as mean ± SD or median and IQR.

LV, left ventricular; RVSP, pulmonary artery systolic pressure; IQR, Interquartile range; SD, standard deviation; E, peak early diastolic velocity; A, peak late diastolic velocity.

Semi-quantitative assessment of mitral regurgitation severity available in n = 2606 (71%).

Mitral inflow assessment available in n = 2757 (75%).

Mitral annular tissue Doppler assessment available in n = 1671 (46%).

Left atrial volume index available in n = 1706 (46%).

RVSP available in n = 1783 (49%).

While measurement of maximal LV wall thickness was statistically different between women and men, there was little practical difference (17.8 ± 5.5 vs. 18.3 ± 5.5 mm, P = 0.016) and no difference in indexed LV mass (150 ± 57 vs. 152 ± 51, P = 0.16). Owing to evolution of echocardiographic diastolic function assessment over time, mitral inflow, tissue Doppler, and left atrial volume assessments were available in many but not all patients (Table 2). Both medial and lateral E/e′ ratios were higher in women (21 ± 10 vs. 16 ± 7 and 16 ± 8 vs. 12 ± 6, respectively, P < 0.0001 for both). In patients with RVSP assessment at echocardiography (n = 1783, 49%), women demonstrated higher estimated RVSP (36 [IQR 30–48] vs. 32 [IQR 28–39] mmHg, P < 0.0001). Women more frequently exceeded RVSP thresholds of 35 and 50 mmHg compared with men (56 vs. 39% and 21 vs. 9%, respectively, P < 0.0001 for both). There was no difference in indexed left atrial volume or presence of left atrial enlargement.

Septal reduction therapy

Myectomy was performed in 1063 patients (29%) at median of 6 (IQR 2–49) days after index evaluation. Although patients who underwent myectomy were younger than those who did not (51.1 ± 14.9 vs. 57.2 ± 15.9 years, P < 0.0001), women (n = 497, 29.9% of all women) and men (n = 566, 28.9% of all men) were equally likely to undergo myectomy (P = 0.24). Women who underwent myectomy were older (53 ± 16 vs. 49 ± 14 years), had higher estimated RVSP (43 ± 16 vs. 35 ± 11 mmHg) and higher resting gradient (67 ± 45 vs. 52 ± 38 mmHg) compared with men who underwent myectomy, but did not differ with regards to septal thickness or provoked gradient. Alcohol septal ablation was performed with greater frequency in women (n = 81, 4.9% of all women) compared with men (n = 61, 3.0% of all men; P = 0.0044), although overall it was utilized less frequently than myectomy. Patients undergoing alcohol septal ablation were older than those undergoing myectomy (62 ± 14 vs. 51 ± 15 years). Women who underwent alcohol septal ablation were significantly older compared with men (66 ± 12 vs. 55 ± 12 years, P < 0.0001) and had higher estimated RVSP (46 ± 22 vs. 34 ± 13 mmHg) but did not differ with regards to septal thickness, resting gradient, or provoked gradient. Fourteen patients (0.4%) underwent both alcohol septal ablation and myectomy. In looking at all septal reduction therapies following referral, women were more likely to undergo intervention (34.4% vs. 30.8%, P = 0.02).

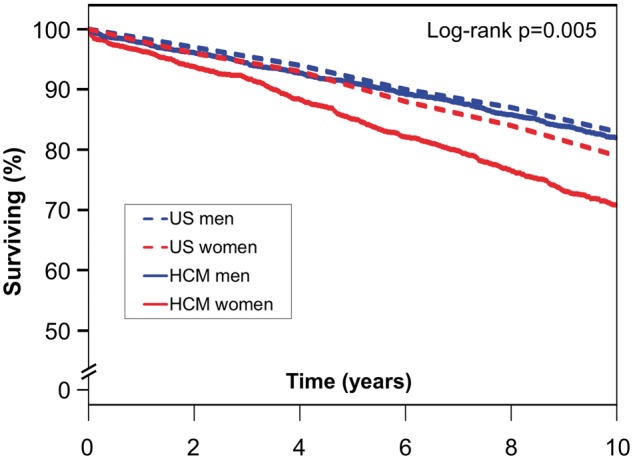

Survival analysis

Median follow-up was 10.9 (IQR 7.4–16.2) years (mean 12.7 ± 8.1 years), encompassing 46 647 patient-years, with 3569 patients (97%) followed beyond 1 year. During follow-up, 1477 deaths occurred. Median survival in patients who died was 9.0 (IQR 4.3–15.0) years after index evaluation. Women had worse survival than men (Figure 1, P < 0.0001). Five- and 10-year survival estimates of women vs. men were 85.1% (CI 83.4%–86.8%) vs. 91.1% (CI 89.9%–92.4%) and 70.8% (CI 68.6%–73.1%) vs. 82.0% (CI 80.3%–83.8%), respectively.

Figure 1.

Survival in all patients stratified by sex. Kaplan–Meier survival curves grouped by sex demonstrate worse survival in women (red) as opposed to men (blue).

When stratified by subjective criteria of symptoms (NYHA class at time of referral), women had worse survival both when more symptomatic (NYHA Class III–IV, n = 1458, P < 0.0001) and less symptomatic (NYHA Class I–II, P < 0.0001). When stratified by objective cardiopulmonary exercise performance (n = 1176, using a cutoff of 75% VO2 predicted), there was no difference in survival between men and women in either group, although only n = 224 deaths were noted within this cohort. Women had worse survival than men following septal reduction therapy (P < 0.0001).

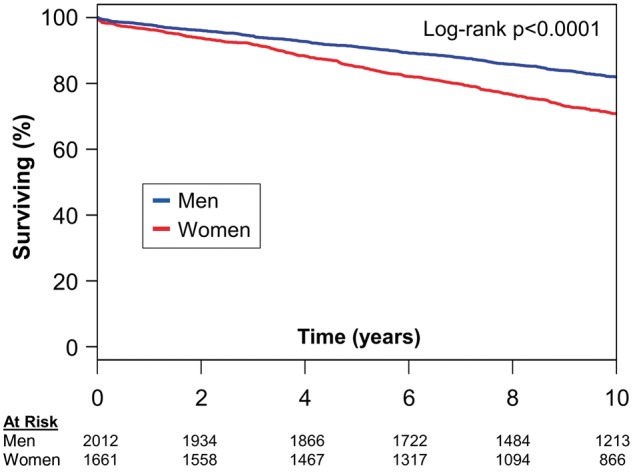

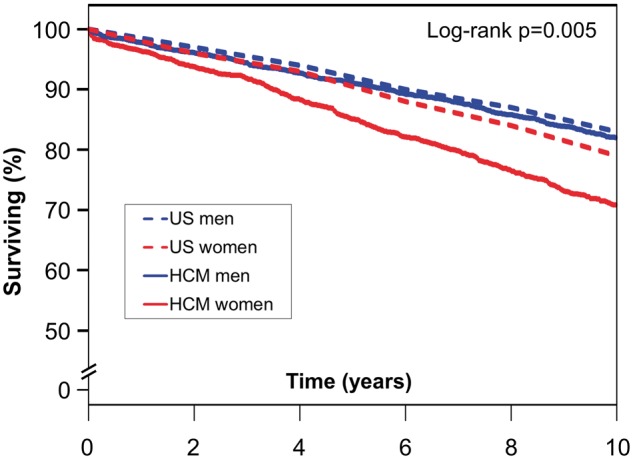

Comparison of HCM patients with an age and sex-matched US population (Take home figure) demonstrated worse survival than expected for both men and women (P = 0.005). Five-year survival estimates demonstrated a difference between expected and observed survival of 5.4% in women (90.5% vs. 85.1%), as compared with 0.9% in men (92.0% vs. 91.1%); 10-year survival estimates revealed a difference of 8.1% in women (78.9% vs. 70.8%), as compared with 0.7% in men (82.7% vs. 82.0%).

Take home figure 2.

Survival comparison of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy to an age- and sex-matched US population. Kaplan–Meier assessment of men with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (solid blue line) compared with an age- and sex-matched US population (dashed blue line). Women with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (solid red line) compared with an age- and sex-matched US population (dashed red line). HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

Hazard modelling

Female sex was a strong univariate predictor of mortality (Table 3). Age, NYHA Class III–IV symptoms, history of AF, coronary artery disease, and systemic hypertension were also predictors of mortality, with ICD implantation and beta receptor antagonist use predictors of lower mortality. Echocardiographic predictors of mortality were LV outflow tract gradient and moderate or greater mitral regurgitation. Female sex remained independently associated with mortality using multivariable modelling inclusive of all statistically significant univariate predictors other than echocardiographic variables: age, NYHA Class III/IV symptoms, and history of AF, coronary artery disease, hypertension, ICD implantation, and beta receptor antagonist use (Table 4). Echocardiographic variables were excluded from main multivariable analysis given reduction of sample size. However, the inclusion of LV outflow tract gradient, LV ejection fraction, and moderate or greater mitral regurgitation to multivariable modelling did not significantly alter the relationship of female sex to mortality. When a propensity score including age, NYHA Class III–IV, ICD implantation, medical therapies, history of AF, coronary artery disease, and hypertension was used to adjust the multivariable Cox proportional hazards model, female sex continued to be associated with mortality; HR 1.17 (95% CI 1.07–1.25), P = 0.0009.

Table 3.

Univariate predictors of mortality

| Variables | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female sex | 1.40 | 1.34–1.46 | <0.0001 |

| Age (per year) | 1.05 | 1.05–1.06 | <0.0001 |

| NYHA Class III–IV | 1.14 | 1.02–1.27 | 0.02 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.79 | 1.59–2.03 | <0.0001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 1.26 | 1.09–1.44 | 0.0001 |

| Hypertension | 1.31 | 1.19–1.46 | <0.0001 |

| ICD implantation | 0.57 | 0.41–0.79 | 0.0006 |

| Beta receptor antagonist use | 0.75 | 0.68–0.83 | <0.0001 |

| Calcium channel antagonist use | 0.94 | 0.85–1.05 | 0.3 |

| Resting LV outflow tract gradient (per mmHg) | 1.002 | 1.000–1.003 | 0.04 |

| Obstructive physiology | 0.98 | 0.87–1.10 | 0.7 |

| Moderate or greater mitral regurgitation | 1.35 | 1.15–1.59 | 0.0003 |

| Maximal wall thickness (per mm) | 0.99 | 0.98–1.00 | 0.2 |

| LV ejection fraction (per %) | 0.99 | 0.99–1.00 | 0.04 |

| Estimated RVSP (per mmHg) | 1.03 | 1.03–1.04 | <0.0001 |

Univariate predictors of all-cause mortality in a large referral HCM population.

HR, hazard ratio; ICD, internal cardioverter-defibrillator; LV, left ventricular; RVSP, right ventricular systolic pressure; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; NYHA, New York Heart Association; CI, confidence interval.

Table 4.

Multivariable predictors of mortality

| Variables | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female sex | 1.13 | 1.03–1.22 | 0.01 |

| Age (per year) | 1.05 | 1.05–1.06 | <0.0001 |

| NYHA Class III–IV | 1.21 | 1.08–1.35 | 0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.57 | 1.38–1.78 | <0.0001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 0.95 | 0.83–1.10 | 0.5 |

| Hypertension | 0.92 | 0.83–1.02 | 0.1 |

| ICD implantation | 0.93 | 0.67–1.30 | 0.7 |

| Beta receptor antagonist use | 0.83 | 0.74–0.92 | 0.0007 |

Multivariable predictors of all-cause mortality.

HR, hazard ratio; ICD, internal cardioverter-defibrillator; NYHA, New York Heart Association; CI, confidence interval.

To assess for the influence of date of referral on survival, visit date as a continuous linear variable was added to the multivariable model shown in Table 4. When adjusted for referral date, female sex remained an independent predictor of mortality [HR 1.13 (1.03–1.22), P = 0.01]. Utilizing a non-linear time adjustment did not alter statistical significance.

In patients with NYHA Class I–II symptoms, the HR for female sex was 1.72 (95% CI 1.52–1.96, P < 0.0001) and after adjustment for age was still borderline significant (HR 1.15, 95% CI 1.00–1.31, P = 0.05), suggesting that age differences within this cohort may account for differences in survival.

Discussion

This large study of patients with HCM from a single tertiary referral centre helps to clarify sex differences in HCM and demonstrates that women with HCM have worse all-cause mortality when compared with men. Women with HCM were referred at an older age with more symptoms, more LV outflow tract obstruction, more PH, higher natriuretic peptides, and worse measures of cardiopulmonary exercise tolerance compared with men. Compared to an age and sex-matched US population, women with HCM had worse relative survival than men. Sex remained predictive of mortality in multivariable modelling.

Male predominance was seen within the study population. Skewing of study populations towards men is a consistent finding amongst studies of HCM.18,34–40 Whether this finding represents decreased disease penetrance in women or reflects clinical recognition/referral practices remains unclear.

Despite similar degrees of hypertrophy, women were more likely to demonstrate obstructive physiology, a finding also consistent with prior studies.18,41,42 This may have contributed to symptomatic differences at presentation, although symptoms may also have been influenced by abnormalities of diastolic function. Women had higher E/e′ ratios, which is known to correlate modestly with higher filling pressures in HCM.43 Women demonstrated more PH, a finding noted in general populations44,45 and in HCM patients undergoing myectomy,32 which may reflect elevated filling pressures, more obstruction, or more reactive pulmonary vasculature. Accordingly, women were more symptomatic in the present study, both on the basis of NYHA class and objective measures of cardiopulmonary exercise tolerance, consistent with other recently reported findings.46

Why do women present with such a different phenotype? This phenomenon may relate to the genetic and endocrine differences between males and females. In experimental models of hypertrophy47 and HCM,48 there are differences in gene expression and associated phenotype between males and females. There is also evidence in humans and experimental animals that sex hormones may modulate the disease phenotype in HCM.49,50 We have previously studied sex differences in patterns of hypertrophy in HCM, albeit in a much smaller cohort, with no significant differences demonstrated.41

Beyond sex differences, gender differences, referring to the psychosocial context in which men and women interface with the healthcare system, are critical.17,51 Women are less aware of their risk of cardiovascular disease and frequently do not have cardiovascular disease discussed with them by their physician.52 In addition, populations of young athletes subjected to cardiovascular disease screening are predominantly male.53–55 It is plausible that women with HCM are under-recognized and their diagnosis delayed until an advanced phenotype is present. This may be in part because of a lack of patient and physician suspicion for the condition and in part because of decreased incidental diagnosis through cardiovascular screening tests.

Previous studies have shown that women with HCM have more major cardiovascular events56 and greater progression to NYHA Class III/IV symptoms,18 but unlike this study have not shown a sex discrepancy in survival.18,19 Our study demonstrates that women with HCM have worse survival than men, a relationship which remained significant in multivariable analyses and propensity score analyses. We believe that these results are not discordant with prior studies, but rather are a clarification of the relationship between sex and survival in a larger, sicker cohort. In comparison to the largest prior study with focus on sex differences within HCM, our population was nearly four times greater in size, included over eight times as many deaths, demonstrated more obstructive physiology, and had a much larger proportion of NYHA Class III or IV patients.18 Our findings are in accord with a prior study of patients undergoing surgical myectomy which demonstrated that female sex was an independent predictor of mortality in long-term post-operative follow-up.57

Women are less likely to be diagnosed with HCM at routine medical examination.18 Furthermore, when diagnosed, women are more likely to carry a diagnosis of system hypertension,41,58 a finding reflected in our data. Despite this, objective measures of systolic blood pressure did not differ at the time of referral evaluation. This may suggest that women with HCM have LV hypertrophy misattributed to systemic hypertension preceding determination of their true underlying pathology. Supporting a hypothesis of misdiagnosis, women with HCM are more likely to be on non-cardiac medications as compared with men,59 which could imply treatment of alternative causes of non-specific symptoms such as dyspnoea. Consistent with prior studies, women were older than men at the time of referral.60,61 Furthermore, women with HCM have been repeatedly shown to be more symptomatic than men,18,59 a finding confirmed in our investigation, which would also support persistent, progressive symptoms eventually unmasking the correct diagnosis.

Beyond symptom assessment, since women have worse survival, is a more aggressive therapeutic approach needed? Beta receptor antagonist at time of referral correlated with improved survival; however, women were less likely to be on beta receptor antagonists. Women were slightly more likely to undergo future reduction therapies, driven by a higher rate of alcohol septal ablation in women, a finding we have previously shown62 but which has not present in all series.63 The 2014 European Society of Cardiology guidelines on diagnosis and management of HCM discuss management of HCM in specific clinical cohorts (athletes, hypertensive patients, and patients with concomitant valvular heart disease) but, apart from discussion of reproduction, do not specifically comment on sex or gender specific approaches to HCM.3 Data herein highlight the clinical importance of differences between men and women with HCM, which we hope future guidelines will emphasize. Our data suggest the need for a different approach to women with HCM: a higher index of diagnostic suspicion and lower threshold for referral for advanced therapies are warranted.

Study limitations

This is a retrospective, single-centre study and is subject to inherent limitations associated with retrospective analyses. All-cause mortality is reported, as the specific cause of death was often unavailable. Whether women have differing rates of cardiac mortality (including SCD) could not be determined by this study and requires further investigation. While a prior study did not find any sex differences in cardiac death, the study population was significantly smaller and a difference in all-cause mortality was not demonstrated,18 unlike the present study.

Our practice represents a high-volume referral centre with long-standing experience in the care of patients with HCM, as demonstrated by both the highly symptomatic patient population and high rate of surgical myectomy. Accordingly, the study may demonstrate referral bias. However, the large patient population herein also includes many patients with less symptomatic status on index evaluation, which provides applicability across HCM. Changes in medication therapy following referral were not quantitatively assessed and have potential to confound results; however the fact that women more frequently underwent septal reduction therapy may imply that less aggressive therapeutic strategies are unlikely to be the major determinant of worse outcomes in women compared with men. Finally, similar to any other HCM cohort, this study may have included patients with hypertrophic heart disease that is difficult to distinguish from hypertrophic changes of the elderly. However, this population had a mean age of 55 years and all included patients were deemed most likely to have true HCM at the time of the comprehensive index evaluation at our institution.

Conclusions

This large HCM cohort revealed significant demographic, haemodynamic, and prognostic differences between men and women with HCM. Women present at an older age and with more symptoms, a phenomenon that may represent delayed diagnosis. Women also demonstrate more echocardiographic evidence of diastolic dysfunction and obstructive physiology despite similar LV mass index. Women with HCM have worse survival compared with men. These numerous significant clinical differences underscore a need for recognition of the sex and gender differences in the diagnosis and care of patients with HCM. Women with HCM may benefit from more intensive surveillance and medical therapies, as well as earlier consideration of septal reduction therapies.

Conflict of interest: J.B.G—consultant (moderate): MyoKardia. B.J.G.—consultant (moderate): MyoKardia. M.J.A.—consultant (moderate): Audentes Therapeutics, Boston Scientific, Giliead Sciences, Medtronic, MyoKardia, and St Jude Medical; other/royalty/intellectual property (significant): AliveCor and Transgenomic (FAMILION). All other authors have no disclosures, financial or otherwise.

References

- 1. Maron BJ, Epstein SE.. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a discussion of nomenclature. Am J Cardiol 1979;43:1242–1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sorajja P, Nishimura RA, Ommen SR, Ackerman MJ, Tajik AJ, Gersh BJ.. Use of echocardiography in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: clinical implications of massive hypertrophy. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2006;19:788–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Authors/Task Force members, Elliott PM, Anastasakis A, Borger MA, Borggrefe M, Cecchi F, Charron P, Hagege AA, Lafont A, Limongelli G, Mahrholdt H, McKenna WJ, Mogensen J, Nihoyannopoulos P, Nistri S, Pieper PG, Pieske B, Rapezzi C, Rutten FH, Tillmanns C, Watkins H.. 2014 ESC Guidelines on diagnosis and management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2014;35:2733–2779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Williams M, Kodali SK, Hahn RT, Humphries KH, Nkomo V, Cohen DJ, Douglas PS, Mack M, McAndrew TC, Svensson L, Thourani VH, Tuzcu EM, Weissman NJ, Kirtane AJ, Leon MB.. Sex-related differences in outcomes following transcatheter or surgical aortic valve replacement in patients with severe aortic stenosis: insights from the PARTNER trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:1522–1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhao ZG, Liao YB, Peng Y, Chai H, Liu W, Li Q, Ren X, Wang XQ, Luo XL, Zhang C, Lu LH, Meng QT, Chen C, Chen M, Feng Y, Huang DJ.. Sex-related differences in outcomes after transcatheter aortic valve implantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2013;6:543–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shapiro S, Traiger GL, Turner M, McGoon MD, Wason P, Barst RJ.. Sex differences in the diagnosis, treatment, and outcome of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension enrolled in the registry to evaluate early and long-term pulmonary arterial hypertension disease management. Chest 2012;141:363–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hsich EM, Grau-Sepulveda MV, Hernandez AF, Peterson ED, Schwamm LH, Bhatt DL, Fonarow GC.. Sex differences in in-hospital mortality in acute decompensated heart failure with reduced and preserved ejection fraction. Am Heart J 2012;163:430–437, 437.e1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dey S, Flather MD, Devlin G, Brieger D, Gurfinkel EP, Steg PG, Fitzgerald G, Jackson EA, Eagle KA.. Sex-related differences in the presentation, treatment and outcomes among patients with acute coronary syndromes: the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events. Heart 2009;95:20–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Warnes CA. Sex differences in congenital heart disease: should a woman be more like a man? Circulation 2008;118:3–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jneid H, Fonarow GC, Cannon CP, Hernandez AF, Palacios IF, Maree AO, Wells Q, Bozkurt B, Labresh KA, Liang L, Hong Y, Newby LK, Fletcher G, Peterson E, Wexler L.. Sex differences in medical care and early death after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 2008;118:2803–2810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Avierinos JF, Inamo J, Grigioni F, Gersh B, Shub C, Enriquez-Sarano M.. Sex differences in morphology and outcomes of mitral valve prolapse. Ann Intern Med 2008;149:787–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. O'Meara E, Clayton T, McEntegart MB, McMurray JJ, Pina IL, Granger CB, Ostergren J, Michelson EL, Solomon SD, Pocock S, Yusuf S, Swedberg K, Pfeffer MA.. Sex differences in clinical characteristics and prognosis in a broad spectrum of patients with heart failure: results of the Candesartan in Heart failure: Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and morbidity (CHARM) program. Circulation 2007;115:3111–3120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. King KM, Ghali WA, Faris PD, Curtis MJ, Galbraith PD, Graham MM, Knudtson ML.. Sex differences in outcomes after cardiac catheterization: effect modification by treatment strategy and time. JAMA 2004;291:1220–1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Habib RH, Zacharias A, Schwann TA, Riordan CJ, Durham SJ, Shah A.. Sex differences in mortality after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. JAMA 2004;292:40–41; author reply 41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Simon T, Mary-Krause M, Funck-Brentano C, Jaillon P.. Sex differences in the prognosis of congestive heart failure: results from the Cardiac Insufficiency Bisoprolol Study (CIBIS II). Circulation 2001;103:375–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Humphries KH, Kerr CR, Connolly SJ, Klein G, Boone JA, Green M, Sheldon R, Talajic M, Dorian P, Newman D.. New-onset atrial fibrillation: sex differences in presentation, treatment, and outcome. Circulation 2001;103:2365–2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fairweather D, Cooper LT Jr, Blauwet LA.. Sex and gender differences in myocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy. Curr Probl Cardiol 2013;38:7–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Olivotto I, Maron MS, Adabag AS, Casey SA, Vargiu D, Link MS, Udelson JE, Cecchi F, Maron BJ.. Gender-related differences in the clinical presentation and outcome of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;46:480–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dimitrow PP, Czarnecka D, Kawecka-Jaszcz K, Dubiel JS.. Sex-based comparison of survival in referred patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Med 2004;117:65–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Richardson P, McKenna W, Bristow M, Maisch B, Mautner B, O'Connell J, Olsen E, Thiene G, Goodwin J, Gyarfas I, Martin I, Nordet P.. Report of the 1995 World Health Organization/International Society and Federation of Cardiology Task Force on the Definition and Classification of cardiomyopathies. Circulation 1996;93:841–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shapiro LM, McKenna WJ.. Distribution of left ventricular hypertrophy in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a two-dimensional echocardiographic study. J Am Coll Cardiol 1983;2:437–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Redfield MM, Rodeheffer RJ, Jacobsen SJ, Mahoney DW, Bailey KR, Burnett JC Jr.. Plasma brain natriuretic peptide concentration: impact of age and gender. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;40:976–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Costello-Boerrigter LC, Boerrigter G, Redfield MM, Rodeheffer RJ, Urban LH, Mahoney DW, Jacobsen SJ, Heublein DM, Burnett JC Jr.. Amino-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide and B-type natriuretic peptide in the general community: determinants and detection of left ventricular dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:345–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Finocchiaro G, Haddad F, Knowles JW, Caleshu C, Pavlovic A, Homburger J, Shmargad Y, Sinagra G, Magavern E, Wong M, Perez M, Schnittger I, Myers J, Froelicher V, Ashley EA.. Cardiopulmonary responses and prognosis in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a potential role for comprehensive noninvasive hemodynamic assessment. JACC Heart Fail 2015;3:408–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Squires RW, Allison TG, Johnson BD, Gau GT.. Non-physician supervision of cardiopulmonary exercise testing in chronic heart failure: safety and results of a preliminary investigation. J Cardiopulm Rehabil 1999;19:249–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Daida H, Allison TG, Squires RW, Miller TD, Gau GT.. Peak exercise blood pressure stratified by age and gender in apparently healthy subjects. Mayo Clin Proc 1996;71:445–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Pellikka PA, Picard MH, Roman MJ, Seward J, Shanewise JS, Solomon SD, Spencer KT, Sutton MS, Stewart WJ.. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2005;18:1440–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tsang TS, Barnes ME, Gersh BJ, Bailey KR, Seward JB.. Left atrial volume as a morphophysiologic expression of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction and relation to cardiovascular risk burden. Am J Cardiol 2002;90:1284–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zoghbi WA, Enriquez-Sarano M, Foster E, Grayburn PA, Kraft CD, Levine RA, Nihoyannopoulos P, Otto CM, Quinones MA, Rakowski H, Stewart WJ, Waggoner A, Weissman NJ.. Recommendations for evaluation of the severity of native valvular regurgitation with two-dimensional and Doppler echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2003;16:777–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Oh JK, Appleton CP, Hatle LK, Nishimura RA, Seward JB, Tajik AJ.. The noninvasive assessment of left ventricular diastolic function with two-dimensional and Doppler echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 1997;10:246–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rudski LG, Lai WW, Afilalo J, Hua L, Handschumacher MD, Chandrasekaran K, Solomon SD, Louie EK, Schiller NB.. Guidelines for the echocardiographic assessment of the right heart in adults: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography endorsed by the European Association of Echocardiography, a registered branch of the European Society of Cardiology, and the Canadian Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2010;23:685–713; quiz 786–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Geske JB, Konecny T, Ommen SR, Nishimura RA, Sorajja P, Schaff HV, Ackerman MJ, Gersh BJ.. Surgical myectomy improves pulmonary hypertension in obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J 2014;35:2032–2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Galasko GI, Lahiri A, Barnes SC, Collinson P, Senior R.. What is the normal range for N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide? How well does this normal range screen for cardiovascular disease? Eur Heart J 2005;26:2269–2276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Autore C, Bernabo P, Barilla CS, Bruzzi P, Spirito P.. The prognostic importance of left ventricular outflow obstruction in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy varies in relation to the severity of symptoms. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;45:1076–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Braunwald E, Lambrew CT, Rockoff SD, Ross J Jr, Morrow AG.. Idiopathic hypertrophic subaortic stenosis. I. A description of the disease based upon an analysis of 64 patients. Circulation 1964;30(Suppl 4):3–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hardarson T, De la Calzada CS, Curiel R, Goodwin JF.. Prognosis and mortality of hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Lancet 1973;2:1462–1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Maron BJ, Casey SA, Poliac LC, Gohman TE, Almquist AK, Aeppli DM.. Clinical course of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a regional United States cohort. JAMA 1999;281:650-5.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Maron BJ, Olivotto I, Spirito P, Casey SA, Bellone P, Gohman TE, Graham KJ, Burton DA, Cecchi F.. Epidemiology of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy-related death: revisited in a large non-referral-based patient population. Circulation 2000;102:858–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Shah PM, Adelman AG, Wigle ED, Gobel FL, Burchell HB, Hardarson T, Curiel R, D, La Calzada C, Oakley CM, Goodwin JF.. The natural (and unnatural) history of hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Circ Res 1974;35(Suppl II):179–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Spirito P, Chiarella F, Carratino L, Berisso MZ, Bellotti P, Vecchio C.. Clinical course and prognosis of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in an outpatient population. N Engl J Med 1989;320:749–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bos JM, Theis JL, Tajik AJ, Gersh BJ, Ommen SR, Ackerman MJ.. Relationship between sex, shape, and substrate in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am Heart J 2008;155:1128–1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dimitrow PP, Czarnecka D, Strojny JA, Kawecka-Jaszcz K, Dubiel JS.. Impact of gender on the left ventricular cavity size and contractility in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol 2001;77:43–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Geske JB, Sorajja P, Nishimura RA, Ommen SR.. Evaluation of left ventricular filling pressures by Doppler echocardiography in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: correlation with direct left atrial pressure measurement at cardiac catheterization. Circulation 2007;116:2702–2708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Badesch DB, Raskob GE, Elliott CG, Krichman AM, Farber HW, Frost AE, Barst RJ, Benza RL, Liou TG, Turner M, Giles S, Feldkircher K, Miller DP, McGoon MD.. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: baseline characteristics from the REVEAL Registry. Chest 2010;137:376–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pugh ME, Hemnes AR.. Pulmonary hypertension in women. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 2010;8:1549–1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Critoph CH, Patel V, Mist B, Elliott PM.. Cardiac output response and peripheral oxygen extraction during exercise among symptomatic hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients with and without left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. Heart 2014;100:639–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. O'Connell TD, Ishizaka S, Nakamura A, Swigart PM, Rodrigo MC, Simpson GL, Cotecchia S, Rokosh DG, Grossman W, Foster E, Simpson PC.. The alpha(1A/C)- and alpha(1B)-adrenergic receptors are required for physiological cardiac hypertrophy in the double-knockout mouse. J Clin Invest 2003;111:1783–1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Maass AH, Ikeda K, Oberdorf-Maass S, Maier SK, Leinwand LA.. Hypertrophy, fibrosis, and sudden cardiac death in response to pathological stimuli in mice with mutations in cardiac troponin T. Circulation 2004;110:2102–2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Haines CD, Harvey PA, Luczak ED, Barthel KK, Konhilas JP, Watson PA, Stauffer BL, Leinwand LA.. Estrogenic compounds are not always cardioprotective and can be lethal in males with genetic heart disease. Endocrinology 2012;153:4470–4479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lind JM, Chiu C, Ingles J, Yeates L, Humphries SE, Heather AK, Semsarian C.. Sex hormone receptor gene variation associated with phenotype in male hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2008;45:217–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Arain FA, Kuniyoshi FH, Abdalrhim AD, Miller VM.. Sex/gender medicine. The biological basis for personalized care in cardiovascular medicine. Circ J 2009;73:1774–1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Mosca L, Ferris A, Fabunmi R, Robertson RM.. Tracking women's awareness of heart disease: an American Heart Association national study. Circulation 2004;109:573–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Corrado D, Basso C, Schiavon M, Thiene G.. Screening for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in young athletes. N Engl J Med 1998;339:364–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Price DE, McWilliams A, Asif IM, Martin A, Elliott SD, Dulin M, Drezner JA.. Electrocardiography-inclusive screening strategies for detection of cardiovascular abnormalities in high school athletes. Heart Rhythm 2014;11:442–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Rowin EJ, Maron BJ, Appelbaum E, Link MS, Gibson CM, Lesser JR, Haas TS, Udelson JE, Manning WJ, Maron MS.. Significance of false negative electrocardiograms in preparticipation screening of athletes for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 2012;110:1027–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ho HH, Lee KL, Lau CP, Tse HF.. Clinical characteristics of and long-term outcome in Chinese patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Med 2004;116:19–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Woo A, Williams WG, Choi R, Wigle ED, Rozenblyum E, Fedwick K, Siu S, Ralph-Edwards A, Rakowski H.. Clinical and echocardiographic determinants of long-term survival after surgical myectomy in obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2005;111:2033–2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lin CL, Chiang CW, Shaw CK, Chu PH, Chang CJ, Ko YL.. Gender differences in the presentation of adult obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with resting gradient: a study of 122 patients. Jpn Circ J 1999;63:859–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Brimacombe M, Walter D, Salberg L.. Gender disparity in a large nonreferral-based cohort of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2008;17:1629–1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Cannan CR, Reeder GS, Bailey KR, Melton LJ 3rd, Gersh BJ.. Natural history of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. A population-based study, 1976 through 1990. Circulation 1995;92:2488–2495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Maron BJ, Casey SA, Haas TS, Kitner CL, Garberich RF, Lesser JR.. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with longevity to 90 years or older. Am J Cardiol 2012;109:1341–1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sorajja P, Valeti U, Nishimura RA, Ommen SR, Rihal CS, Gersh BJ, Hodge DO, Schaff HV, Holmes DR Jr.. Outcome of alcohol septal ablation for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2008;118:131–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Veselka J, Krejci J, Tomasov P, Zemanek D.. Long-term survival after alcohol septal ablation for hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy: a comparison with general population. Eur Heart J 2014;35:2040–2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]