We developed a stretchable organic optoelectronic sensorimotor synapse to mimic a biological optical sensory nervous system.

Abstract

Emulation of human sensory and motor functions becomes a core technology in bioinspired electronics for next-generation electronic prosthetics and neurologically inspired robotics. An electronic synapse functionalized with an artificial sensory receptor and an artificial motor unit can be a fundamental element of bioinspired soft electronics. Here, we report an organic optoelectronic sensorimotor synapse that uses an organic optoelectronic synapse and a neuromuscular system based on a stretchable organic nanowire synaptic transistor (s-ONWST). The voltage pulses of a self-powered photodetector triggered by optical signals drive the s-ONWST, and resultant informative synaptic outputs are used not only for optical wireless communication of human-machine interfaces but also for light-interactive actuation of an artificial muscle actuator in the same way that a biological muscle fiber contracts. Our organic optoelectronic sensorimotor synapse suggests a promising strategy toward developing bioinspired soft electronics, neurologically inspired robotics, and electronic prostheses.

INTRODUCTION

Our human body performs not only myriads of sensing functions including external stimuli (light, pressure, temperature, and humidity) (1–5) and biological signals (pulse pressure, cardiac signals, and brainwaves) (4–7) but also both neural signal processing and motor responses. All signals involved in these processes are transferred through synapses and synergistically combined to complete the complicated human neural system. By mimicking biological synapses in the human sensorimotor nervous system, a neurologically inspired electronic synapse that processes neural signals received from artificial sensory organs and produces informative synaptic responses and motor outputs can be a critical element for an artificial sensorimotor nervous system of bioinspired soft electronics and neurorobotics (8).

Organic artificial synapses represent a viable approach to developing neurologically inspired electronic devices by emulating biological synapses (8–11) with the distinctive advantages of (i) extremely low energy consumption and (ii) high robustness in their mechanical flexibility (8–10). To date, however, the development of organic artificial synapses remains rudimentary because most research has focused only on the development of materials and individual devices to emulate synaptic responses and memory properties in a brain (8–11). Mimicking complicated biological sensory and motor synapses in the human body has remained a daunting challenge.

Light cognition is an important sensory function for bioinspired electronics (12–15), for example, an artificial visualization system. In addition, light-driven operation of an artificial sensory system combined with motor control enables the development of optical wireless control of bioinspired soft electronics. Moreover, this light cognition by artificial sensorimotor synapses facilitates optical wireless operation, communication, and information transmission of soft robotics in the future ubiquitous environment. In particular, a self-powered light sensory synapse will enable low-energy operation of neurologically inspired electronics.

Here, we aim to demonstrate an organic optoelectronic sensorimotor artificial synapse that is based on a stretchable organic nanowire synaptic transistor (s-ONWST) to perceive and propagate optical sensory inputs and to generate informative synaptic responses and subsequent motor outputs. Specifically, this sensorimotor synapse combined with a photodetector converts patterned optical stimuli into potentiated synaptic responses through the s-ONWST to conduct optical wireless communication of light fidelity and forms an artificial neuromuscular junction to activate artificial muscle actuator with biomimetic muscular contraction mechanism, which cannot be achieved by conventional direct operation of the artificial muscle actuator (16, 17). We believe that our organic optoelectronic sensorimotor synapse would open a new era of bioinspired electronics for next-generation prosthetics and neurorobotics.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Design of organic optoelectronic synapse and neuromuscular system

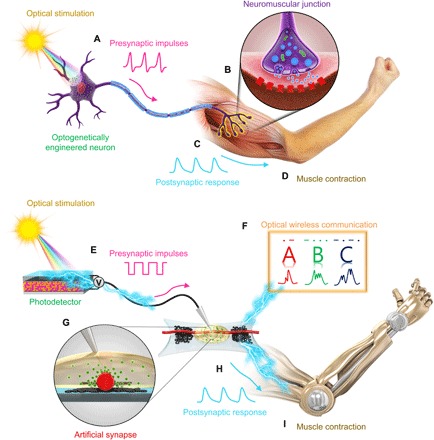

In optogenetics, the contraction of biological muscle fibers can be controlled by optical stimulation of motor neurons that are genetically modified to be photosensitive (Fig. 1A); this approach is promising to restore the motor function of defective neuromuscular systems (18–20). A biological neuromuscular junction (Fig. 1B) is a chemical synapse that transmits presynaptic action potentials from lower motor neurons (α-motor neurons) to the adjacent skeletal muscle fibers by delivering the neurotransmitter acetylcholine to generate excitatory postsynaptic potentials (Fig. 1C), ultimately resulting in muscle contraction (Fig. 1D). To realize a bioinspired movement system like that of humans, development of a neuromuscular electronic system is necessary.

Fig. 1. Biological and organic optoelectronic synapse and neuromuscular electronic system.

(A to D) In a biological system, (A) light stimulates a biological motor neuron that has photosensitive protein expression, and an action potential is thus generated. (B and C) A chemical synapse of a neuromuscular junction transmits the potentials to a muscle fiber, (D) which causes the muscle to contract. Analogously, (E to I) in an organic artificial system, (E) light triggers a photodetector to generate output voltage spikes. (H and G) The voltage spikes produce electrical postsynaptic signals from an s-ONWST to activate an artificial muscle actuator, (I) which the artificial muscle then contracts. (F) Optical wireless communication via organic optoelectronic synapse with patterned light signals representing the International Morse code of “ABC.”

Our organic optoelectronic synapse generates typical excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) when triggered by various patterns of optical signals as presynaptic impulses. A photodetector is stimulated by optical pulses of various wavelengths in infrared, visible, and ultraviolet regions (Fig. 1E). The optical wireless signals subsequently generate output voltage pulses that are applied to s-ONWSTs as presynaptic spikes to trigger EPSCs. By converting optical signals of the International Morse code to distinct EPSC signals, the organic optoelectronic synapse provides an optical wireless communication method for human-machine interfaces (Fig. 1F).

The s-ONWST also constitutes a neuromuscular electronic system, along with an artificial muscle actuator, to realize an artificial motor nervous system by mimicking a biological neuromuscular system. A presynaptic electrical impulse was similarly transmitted from a gate electrode to organic nanowires (ONWs; Fig. 1E). This transmission is a consequence of ion migration in the electrolyte (Fig. 1G) that generates postsynaptic electrical responses (Fig. 1H) that can control our artificial muscles (Fig. 1I). The artificial optical sensorimotor system is composed of components that correspond to each component of the biological system (Table 1). The artificial synaptic cleft of the ion gel electrolyte is ionically conducting and electronically insulating, so the ions can migrate to the ONW channel upon presynaptic gate voltage spikes to result in an increase in postsynaptic drain current (fig. S1). Thus, our optical sensory neuromuscular electronic system enables wireless activation of artificial muscle and thereby facilitates optical wireless control of soft electronic devices.

Table 1. Comparison of biological and optical neuromuscular electronic systems.

| Biological system | Artificial system | |

| Sensorimotor neuron | Presynaptic membrane | Gate electrode |

| Presynaptic potential | Gate voltage | |

| Photosensitive protein | Photodetector | |

| Neuromuscular junction |

Synaptic cleft | Ion gel electrolyte |

| Neurotransmitter | Anion | |

| Skeletal muscle | Postsynaptic membrane | ONW |

| Postsynaptic potential | Drain current | |

| Muscle fiber | Polymer actuator |

Fabrication and electrical characteristics of s-ONWST

We hypothesize that biomimetic soft electronics that are both flexible and stretchable should be a viable approach for “soft” neurorobotic applications. Specifically, we aim to develop organic artificial synaptic devices that (i) can mimic the “flexible and winding” fibril morphology of biological neurons and (ii) are mechanically stretchable and durable under various motions related to bending, folding, twisting, and stretching of soft electronics. These two attributes have been difficult to achieve using conventional rigid inorganic artificial synapses (21–24).

ONWs can be readily fabricated by electrospinning with parallel electrodes (fig. S2A). The ONW was composed of a homogeneous mixture of fused thiophene diketopyrrolopyrrole (FT4-DPP)–based conjugated polymer and polyethylene oxide [PEO (7:3, w/w); fig. S2, B and C] and had an average diameter of 664 nm (SD = 47 nm; fig. S2, D and E). Inclusion of a small amount of high–molecular weight polymer PEO (MW: 400,000 g/mol) prevents wire breakage, generates continuous ONWs (25), and improves ion transportation in the ONW. A single nanowire (NW) was transferred onto 100% prestrained styrene ethylene butylene styrene (SEBS) rubbery substrate on which carbon nanotube (CNT) source and drain (S/D) electrodes (Fig. 2A) had been patterned. After the strain was released, the elastic substrate contracted and the ONW became wavy; it retained this configuration after repeated stretching to 100% strain (Fig. 2B). With a high-capacitance ion gel electrolyte, s-ONWSTs were fabricated (see Materials and Methods). In current-voltage (I-V) curves, the transistor showed the typical behavior of ion gel–based electrochemical transistors (Fig. 2C) (26–28). The formation of an electric double layer at the gate-electrolyte interface and the electrolyte-semiconductor interface resulted in a behavior similar to biological synaptic plasticity. The FT4-DPP–based polymer NW displayed both small hysteresis and short memory retention and is therefore a suitable candidate to mimic the short build and decay times (<1 s) of biological sensorimotor synapses. Our previously reported poly(3-hexylthiophene-2,5-diyl) (P3HT) NW had large hysteresis and relatively long memory retention (10) and was therefore not suitable to emulate biological sensorimotor synapses.

Fig. 2. Fabrication and electrical characteristics of s-ONWST.

(A) Fabrication procedure of s-ONWST based on a single ONW. An electrospun single ONW was first transferred onto prestretched rubbery SEBS substrate and subsequently buckled when the film contracted after the strain was released. (B) Optical microscopy image of a wavy NW stretched from 0 to 100% strain. (C) I-V characteristics of s-ONWST at 0, 50, and 100% strains. Blue arrows: clockwise hysteresis. (D) Maximum drain current and mobility as a function of various strains along the channel length and width directions.

In our s-ONWSTs, the maximum drain current (~1 μA) and the carrier mobility were maintained up to 100% strain along both the channel length and width directions (Fig. 2D and table S1). These electrical properties were unaffected even after 50 cycles at 100% strain in both directions (fig. S3 and table S2).

Synaptic characteristics of s-ONWST

Our artificial synapse based on ion gel–gated electrochemical transistor emulates a biological synapse in a sensorimotor nervous system (Fig. 3A). In biological synapses, action potentials from the presynaptic neuron are transferred to the postsynaptic neuron by migration of neurotransmitters across the synaptic cleft. These neurotransmitters at the receptors on postsynaptic membrane then induce postsynaptic signals. Similarly, in our device, the negative presynaptic voltage spikes attract temporary accumulation of anions near the surface of the ONW; this anion accumulation subsequently induces a hole-transporting channel in the ONW and results in an EPSC with the needed driving voltage (fig. S1). A single presynaptic spike (−1 V, 120 ms) triggered an EPSC of −6.43 nA and was observed to decay to a resting current Iresting ≈ −0.2 nA within a few seconds because of the back diffusion of anions through the electrolyte (Fig. 3B). In a biological synapse, neural facilitation, that is, paired-pulse facilitation (PPF), evoked by a consecutively applied pair of pulse separated by a short interspike interval Δt potentiates postsynaptic signals. Reduction in Δt amplifies the postsynaptic potentiation (this response is a common property of biological synapses), leading to a short-term synaptic enhancement, for example, strengthening of temporal postsynaptic plasticity in sensory and motor nervous systems (9, 21, 29). In the artificial synapse, paired pulses with Δt = 120 ms amplified the second EPSC peak (A2) ~1.34 times compared to the first EPSC peak (A1) (Fig. 3B); this phenomenon is due to the additional anion accumulation as induced by the second pulse, even before the anions accumulated during the first pulse have completely diffused away. Hence, as the net anion concentration near the NW increased, the EPSC increased correspondingly. As Δt increased, the number of residual anions accumulated by the first peak decreased, so PPF (A2/A1) decreased (Fig. 3C). Again, this response is similar to the PPF of biological synapses (29).

Fig. 3. Synaptic characteristics of s-ONWST.

(A) Neural signal transmission from preneuron to postneuron through a biological synapse (top) and an artificial synapse (bottom). (B) EPSCs triggered by single and double spikes (each spike: −1 V, 120 ms). A1 and A2 are EPSCs of the first and second spikes, respectively, separated by Δt = 120 ms. (C to E) Postsynaptic characteristics of stretched artificial synapse from 0 to 100% strains; (C) PPF (A2/A1) as a function of 120 ≤ Δt ≤ 920 ms, (D) spike voltage–dependent plasticity (SVDP) with various gate voltages from −0.3 to −1 V, and (E) spike number–dependent plasticity (SNDP) with 1 to 50 spikes. (F and G) Spike frequency–dependent plasticity (SFDP) characteristics with spike frequency from 0.3 to 5 Hz; (F) maximum EPSCs and (G) EPSC gain (A10/A1) of stretched artificial synapse from 0 to 100% strains.

s-ONWSTs operated stably with various synaptic properties, for example, PPF (A2/A1), SVDP, SNDP, SFDP, and EPSC gain (A10/A1), at 100% strain. These postsynaptic responses are triggered by different presynaptic spike patterns (for example, Δt, strength of spikes, number of spikes, and spike frequency) and present features that can be exploited to develop neuroinspired electronics by mimicking the biological synapse. EPSC gain (A10/A1) related to a functional dynamic filtering behavior of a biological synapse was determined by the ratio of the 10th EPSC peak (A10) to the first EPSC peak (A1) (21, 22, 30). Depending on the applied presynaptic spike voltage (−0.3 to −1 V in increments of −0.1 V), the magnitude of EPSC increased from −1.96 to −6.66 nA; this trend occurred because the increase in voltage subsequently increases the amount of accumulated ions (Fig. 3D). As the number of applied presynaptic spikes nSPIKE increased from 1 to 50, EPSC increased as a consequence of the growing accumulation of anions (Fig. 3E). The frequency of presynaptic signals fSPIKE is responsible for firing postsynaptic signals in the biological synapse. In our fabricated artificial synapse, EPSC increased steadily as fSPIKE increased (Fig. 3F and fig. S4). As fSPIKE increased and Δt decreased, the EPSC gain (A10/A1) increased gradually from 1.07 to 1.55; this change is again similar to the dynamic high-pass filtering of signal transmission that occurs in biological synapses (Fig. 3G) (21, 22, 30).

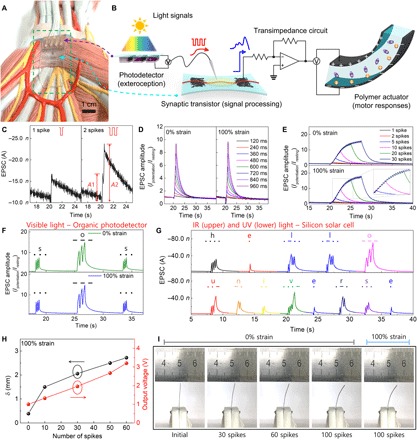

Organic optoelectronic synapse and neuromuscular electronic system

Next, an organic optoelectronic synapse was fabricated with a photodetector and s-ONWST (Fig. 4, A and B). Exposure to light signal sources causes the photodetector to generate voltage spikes that stimulate the s-ONWST to emit EPSCs. nSPIKE was controlled from 1 to 50, and their duration dSPIKE was varied from 120 to 960 ms. The response time of an organic photodetector is <1 ms (31), which is much smaller than dSPIKE = 120 ms. Therefore, temporal mismatch between light signals and presynaptic voltage generation is not a problem. Each visible light pulse induced an output spike voltage of −1.1 V from the organic photodetector (fig. S5 and fig. S6A). A single light spike stimulated an EPSC of −16.7 nA, and double light spikes yielded PPF (A2/A1) of 1.42 (A2 = −23.8 nA; A1 = −16.7 nA; Fig. 4C). Spike duration–dependent plasticity (SDDP) and SNDP characteristics were similar in the device at 100% strain to those in the device at 0% strain. As dSPIKE was increased from 120 to 960 ms, EPSC amplitude Ipotentiation/Iresting increased from 1.2 to 9.7 (Fig. 4D). As nSPIKE increased, EPSC amplitude increased linearly until nSPIKE = 10 (Fig. 4E); at nSPIKE > 10, the increase gradually slowed to an asymptote (Fig. 4E). These behaviors are analogous to biological muscle tension responses during contractions of twitch, summation, and incomplete tetanus (fig. S7) (32, 33).

Fig. 4. Organic optoelectronic synapse and neuromuscular electronic system.

(A) Photograph of organic optoelectronic synapse on an internal human structure model. (B) Configuration of organic optoelectronic synapse (photodetector and artificial synapse) and neuromuscular electronic system (artificial synapse, transimpedance circuit, and artificial muscle actuator). (C) EPSCs triggered by single and double visible light spikes (each spike generated presynaptic voltage of −1.1 V for 120 ms). PPF (A2/A1) = 1.42. (D and E) Visible light–triggered EPSC amplitudes of s-ONWST from 0 to 100% strains; (D) SDDP from 120 to 960 ms and (E) SNDP with 1 to 30 spikes. (F) Visible light–triggered EPSC amplitudes of s-ONWST with the International Morse code of “SOS,” which is the most common distress signal. (G) Infrared (IR) and ultraviolet (UV) light–triggered EPSC amplitudes of s-ONWST with the International Morse code of “HELLO UNIVERSE.” (H) Maximum δ of polymer actuator and output voltage generated by s-ONWST according to 0 ≤ nSPIKE ≤ 60 and (I) digital images of the polymer actuator according to 0 ≤ nSPIKE ≤ 100 with 0 or 100% strain.

To demonstrate the potential of our organic optoelectronic synapse as an optical wireless communication method for human-machine interfaces, we showed that the s-ONWST can react to patterns of visible light that represent the International Morse code, in which every letter of the English alphabet can induce a distinct EPSC amplitude response (fig. S8). Every letter was linearly correlated with the sum of EPSC amplitude peak values (fig. S9). “SOS,” representing the standard emergency signal, was expressed with EPSC amplitude of an artificial synapse at both 0 and 100% strains (Fig. 4F); stretching the device did not result in any notable changes in its response. In addition to visible light, we input short messages (“HELLO” and “UNIVERSE”) by using invisible infrared (940 nm) and ultraviolet (365 nm) light and a silicon solar cell (Fig. 4G and fig. S6B). These EPSC responses showed that our system can be applied to light fidelity in the future. We are now applying this communication method toward remote control of a bioinspired artificial muscle.

Last, a complete neuromuscular electronic system was assembled by connecting an s-ONWST to a polymer actuator through a transimpedance circuit (fig. S10). EPSCs from the organic optoelectronic synapse were converted to voltage signals to operate our fabricated polymer actuator. The low voltage–driven polymer actuator was composed of imidazole (Im)–doped poly(styrenesulfonate-b-methylbutylene) (PSS-b-PMB) block copolymers, a zwitterion of 3-(1-methyl-3-imidazolium) propanesulfonate, and CNT electrodes that had been fabricated as reported previously (16). S/D voltage was applied to the source electrode of the artificial synapse, rather than to the drain electrode (fig. S11). This connection was necessary because the drain electrode was connected to the circuit to convert currents to output voltages, such that the polymer actuator can be operated. We used the organic photodetector and visible light in this system. Before the device was illuminated, the Iresting of the artificial synapse generated a small voltage (~1 V), which resulted in a slight contraction of the artificial muscle (Fig. 4, H and I). When short pulses of light were applied, the EPSCs were converted to voltages to operate the actuator. The output voltage and displacement δ of the actuator all increased as nSPIKE increased (Fig. 4, H and I). Specifically, δ with 10 spikes at 1.5 mm was increased to 2.7 mm with 60 spikes as the output voltage was increased from 1.3 to 3.2 V (Fig. 4H and table S3). The polymer actuator operated stably with s-ONWST at both 0 and 100% strains; it had δ = 5.3 and 5.4 mm, respectively, after 100 spikes (Fig. 4I and movie S1). Direct connection of the polymer actuator and the voltage source without the artificial synapse can produce constantly very small δ (<100 μm) in the actuator at low voltages, but not a gradual increase of actuation upon repeated voltage pulses (16, 17). These results collectively demonstrated that our fabricated organic optoelectronic sensorimotor synapse is a viable platform for optical stimulation to actuate artificial muscle remotely, which mimics the biological muscle tension response during contraction with action potentials.

CONCLUSION

We have demonstrated the first neurologically inspired organic optoelectronic sensorimotor synapse using an organic optoelectronic synapse and a neuromuscular system based on s-ONWST. This synapse has potential to be an element in an artificial sensorimotor nervous system of soft electronics and neurorobotics. Our highly robust s-ONWSTs showed stable I-V characteristics and various typical postsynaptic behaviors, including EPSC, PPF, SVDP, SNDP, SFDP, and high-pass filtering at both 0 and 100% strains. Our s-ONWSTs can be further used as organic optoelectronic synapses that exploit the output voltage of a photodetector by converting light signals to presynaptic spikes to trigger postsynaptic potentiation of the artificial synapse. This organic optoelectronic synapse then actuated an artificial muscle; this motor response in our neuromuscular system is analogous to the biological muscle tension responses during contraction. Patterned light signals can successfully convey Morse code onto the s-ONWST; this ability suggests a novel potential optical wireless communication of light fidelity for human-machine interfaces. This combination of relevant functionalities of optics, electronics, and biological technology demonstrates that our organic optoelectronic sensorimotor synapse represents a promising strategy for the development of next-generation biomimetic soft electronics, soft robotics, neurorobotics, and electronic prostheses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Electrospinning of single FT4-DPP–based polymer NW

An FT4-DPP–based polymer poly[(3,7-bis(heptadecyl)thieno[3,2-b]thieno[2′,3′:4,5]thieno[2,3-d]thiophene-5,5′-diyl)(2,5-bis(8-octyloctadecyl)-3,6-di(thiophen-2-yl)pyrrolo[3,4-c]pyrrole-1,4(2H,5H)-dione-5,5′-diyl)] (Mw: 33,000 g/mol; PDI: 2, Corning Inc.) and PEO [MW = 400,000 g/mol (7:3, w/w); (Sigma-Aldrich)] were dissolved in chloroform. A homogeneous and viscous solution was achieved after magnetic stirring for 2 hours at 500 rpm and 50°C. Electrospinning was conducted at an applied voltage of 3 kV, tip-to-collector distance of 15 cm, and a solution feeding rate of 1 μl/min. During electrospinning, single NWs were aligned between parallel electrodes.

Fabrication of stretchable synaptic transistor

S/D electrodes of single-wall CNTs (SWCNTs) were spray-coated on SiO2/Si substrate and transferred on SEBS substrate. The single aligned NW was transferred onto a prestretched SEBS substrate, and then, the tension on the substrate was released slowly. Ion gel gate dielectric composed of poly(styrene-b-methyl methacrylate-b-styrene) (PS-PMMA-PS) triblock copolymer and 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide ([EMIM][TFSI]) ionic liquid dissolved in ethyl acetate (0.7:9.3:90, w/w) was drop-cast on the FT4-DPP–based polymer NW. The device was dried under vacuum for 6 hours to remove the solvent, and then, the device’s electrical characteristics were measured in a glove box filled with N2.

Fabrication of organic photodetector

Bulk heterojunction inverted organic photovoltaic was fabricated. ZnO layer (30 nm) was formed by spin-coating of ZnO precursor solution of zinc acetate dihydrate (Zn(CH3COO)2·2H2O) (Sigma-Aldrich) and 2-methoxyethanol (CH3OCH2CH2OH) (Sigma-Aldrich) on the indium tin oxide substrate. The mixture solution of P3HT (Sigma-Aldrich) and [6,6]-phenyl-C(61)-butyric acid methyl ester (PC60BM) (Sigma-Aldrich) in chlorobenzene was spin coated (150 nm) on the ZnO layer. Then, poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) doped with poly(4-styrenesulfonate) (CLEVIOS AI4083) was coated (40 nm) as a hole extraction layer and then annealed at 150°C for 10 min. Ag (100 nm) was thermally deposited as an anode under high vacuum. To achieve large output presynaptic voltage with magnitude greater than −1 V, three subpixels (total area, ~0.48 cm2) were connected in series; the combination generated VOC = −1.1 V when photostimulation was applied from a commercial white light-emitting diode (LED) bulb (Solarzen T10 5450 3 chip 4P) connected to a semiconductor parameter analyzer (Keysight B1500) that makes patterned voltage spikes. A commercial silicon solar cell was used to detect light from commercial infrared (940 nm) and ultraviolet (365 nm) LEDs.

Fabrication of polymer actuator

A sulfonated block copolymer and zwitterion were synthesized, and the polymer actuator was fabricated as described previously (16). To prepare PSS-b-PMB block copolymer doped with Im, 5 weight % (wt %) Im and PSS-b-PMB block copolymer mixture was dissolved in methanol. Im-doped polymers were achieved by solution casting and vacuum drying. Im-doped polymers were redissolved in a solvent mixture (4:1, v/v) of methanol and tetrahydrofuran, and then, zwitterions were added to the mixed solution. An aluminum mold (1 cm by 1.5 cm) was used to prepare polymer membranes by solution casting in Ar atmosphere for 2 days at room temperature, and then, polymer films were dried in vacuum at 70°C for a week. The polymer membranes were pressed at 200 kgf cm−2 at 25°C for 1 hour. SWCNT electrodes contain 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate ([EMIM][BF4]) (Sigma-Aldrich), poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropropylene) (Kynar Flex 2801, Arkema Chemical Inc.), and SWCNTs (Sigma-Aldrich) (2.5:1.5:1.0, w/w). To achieve the polymer actuators, the polymer membrane was sandwiched with 10-μm-thick SWCNT electrodes by hot pressing. The actuators measured 19 mm by 1 mm by 90 μm.

Characterization

The electrical characteristics of s-ONWST were measured using a semiconductor parameter analyzer (Keithley 4200 and Keysight B1500) under N2 in a glove box, and the response for the International Morse code was measured under ambient conditions. The morphology of ONW was measured using an optical microscope (Leica DM4000M), a scanning electron microscope (FEI XL30 Sirion), and a transmission electron microscope (FEI Tecnai F20 at 200 kV). The chemical composition of ONW was determined using an energy-dispersive x-ray spectroscope (FEI Tecnai F20 at 200 kV).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Corning Cooperation for supporting FT4-DPP–based conjugated polymer. Funding: This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (Ministry of Science and ICT) (NRF-2016R1A3B1908431). This work was also supported by Creative-Pioneering Researchers Program through Seoul National University (SNU). Author contributions: Y.L., J.Y.O., Z.B., and T.-W.L. conceived and designed the experiments. Y.L. and J.Y.O. performed the experiments. Y.L., J.Y.O., W.X., O.K., T.R.K., J.K., Y.K., D.S., J.B.-H.T., M.J.P., Z.B., and T.-W.L. analyzed the data. Y.L., J.Y.O., J.B.-H.T., Z.B., and T.-W.L. co-wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript. Competing interests: Y.L., Y.K., Z.B., and T.-W.L. are co-inventors of patent applications filed by Seoul National University and Stanford University (KR patent application no. 10-2018-0062069, filed 30 May 2018; U.S. patent application no. 62/678,158, filed 30 May 2018) related to this work. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/4/11/eaat7387/DC1

Additional supporting information

Fig. S1. Working mechanism of s-ONWST.

Fig. S2. Fabrication and morphology of ONW.

Fig. S3. Electrical characteristics of s-ONWST.

Fig. S4. SFDP of s-ONWST.

Fig. S5. Current density-voltage (J-V) characteristics of organic photodetector.

Fig. S6. Output characteristics of the photodetectors with different light spike frequency.

Fig. S7. Frequency-dependent biological muscle contraction and EPSCs of s-ONWST.

Fig. S8. A novel optical wireless communication method of human-machine interface.

Fig. S9. Correlation between EPSC amplitude response and the International Morse code of English letters.

Fig. S10. Full circuit diagram of transimpedance circuit.

Fig. S11. Operating voltage shift of s-ONWST to connect the transimpedance circuit.

Table S1. Summary of electrical characteristics of s-ONWST as function of strain in channel length and width directions.

Table S2. Summary of electrical characteristics of s-ONWST after stretching cycles at 100% strain in channel length and width directions.

Table S3. Maximum δ of polymer actuator and output voltage generated by s-ONWST according to the number of light spikes.

Movie S1. Operation of an artificial muscle actuator by an optical sensory neuromuscular electronic system.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Kaltenbrunner M., Sekitani T., Reeder J., Yokota T., Kuribara K., Tokuhara T., Drack M., Schwödiauer R., Graz I., Bauer-Gogonea S., Bauer S., Someya T., An ultra-lightweight design for imperceptible plastic electronics. Nature 499, 458–463 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tee B. C.-K., Chortos A., Berndt A., Nguyen A. K., Tom A., McGuire A., Lin Z. C., Tien K., Bae W.-G., Wang H., Mei P., Chou H.-H., Cui B., Deisseroth K., Ng T. N., Bao Z., A skin-inspired organic digital mechanoreceptor. Science 350, 313–316 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lipomi D. J., Vosgueritchian M., Tee B. C.-K., Hellstrom S. L., Lee J. A., Fox C. H., Bao Z., Skin-like pressure and strain sensors based on transparent elastic films of carbon nanotubes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 6, 788–792 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Someya T., Bao Z., Malliaras G. G., The rise of plastic bioelectronics. Nature 540, 379–385 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chortos A., Liu J., Bao Z., Pursuing prosthetic electronic skin. Nat. Mater. 15, 937–950 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee S., Reuveny A., Reeder J., Lee S., Jin H., Liu Q., Yokota T., Sekitani T., Isoyama T., Abe Y., Suo Z., Someya T., A transparent bending-insensitive pressure sensor. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 472–478 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sekitani T., Yokota T., Kuribara K., Kaltenbrunner M., Fukushima T., Inoue Y., Sekino M., Isoyama T., Abe Y., Onodera H., Someya T., Ultraflexible organic amplifier with biocompatible gel electrodes. Nat. Commun. 7, 11425 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim Y., Chortos A., Xu W., Liu Y., Oh J. Y., Son D., Kang J., Foudeh A. M., Zhu C., Lee Y., Niu S., Liu J., Pfattner R., Bao Z., Lee T.-W., A bioinspired flexible organic artificial afferent nerve. Science 360, 998–1003 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu W., Min S.-Y., Hwang H., Lee T.-W., Organic core-sheath nanowire artificial synapses with femtojoule energy consumption. Sci. Adv. 2, e1501326 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van de Burgt Y., Lubberman E., Fuller E. J., Keene S. T., Faria G. C., Agarwal S., Marinella M. J., Alec Talin A., Salleo A., A non-volatile organic electrochemical device as a low-voltage artificial synapse for neuromorphic computing. Nat. Mater. 16, 414–418 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gkoupidenis P., Schaefer N., Garlan B., Malliaras G. G., Neuromorphic functions in PEDOT:PSS organic electrochemical transistors. Adv. Mater. 27, 7176–7180 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Song Y. M., Xie Y., Malyarchuk V., Xiao J., Jung I., Choi K.-J., Liu Z., Park H., Lu C., Kim R.-H., Li R., Crozier K. B., Huang Y., Rogers J. A., Digital cameras with designs inspired by the arthropod eye. Nature 497, 95–99 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu X., Lu W. D., Optogenetics-inspired tunable synaptic functions in memristors. ACS Nano 12, 1242–1249 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qin S., Wang F., Liu Y., Wan Q., Wang X., Xu Y., Shi Y., Wang X., Zhang R., A light-stimulated synaptic device based on graphene hybrid phototransistor. 2D Mater. 4, 035022 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gkoupidenis P., Rezaei-Mazinani S., Proctor C. M., Ismailova E., Malliaras G. G., Orientation selectivity with organic photodetectors and an organic electrochemical transistor. AIP Adv. 6, 111307 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim O., Kim H., Choi U. H., Park M. J., One-volt-driven superfast polymer actuators based on single-ion conductors. Nat. Commun. 7, 13576 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim O., Shin T. J., Park M. J., Fast low-voltage electroactive actuators using nanostructured polymer electrolytes. Nat. Commun. 4, 2208 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bryson J. B., Machado C. B., Crossley M., Stevenson D., Bros-Facer V., Burrone J., Greensmith L., Lieberam I., Optical control of muscle function by transplantation of stem cell–derived motor neurons in mice. Science 344, 94–97 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Llewellyn M. E., Thompson K. R., Deisseroth K., Delp S. L., Orderly recruitment of motor units under optical control in vivo. Nat. Med. 16, 1161–1165 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Magown P., Shettar B., Zhang Y., Rafuse V. F., Direct optical activation of skeletal muscle fibres efficiently controls muscle contraction and attenuates denervation atrophy. Nat. Commun. 6, 8506 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu G., Zhang J., Wan X., Yang Y., Jiang S., Chitosan-based biopolysaccharide proton conductors for synaptic transistors on paper substrates. J. Mater. Chem. C 2, 6249–6255 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu R., Zhu L. Q., Wang W., Hui X., Liu Z. P., Wan Q., Biodegradable oxide synaptic transistors gated by a biopolymer electrolyte. J. Mater. Chem. C 4, 7744–7750 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ohno T., Hasegawa T., Tsuruoka T., Terabe K., Gimzewski J. K., Aono M., Short-term plasticity and long-term potentiation mimicked in single inorganic synapses. Nat. Mater. 10, 591–595 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee D., Moon K., Park J., Park S., Hwang H., Trade-off between number of conductance states and variability of conductance change in Pr0.7Ca0.3MnO3-based synapse device. Appl. Phys. Lett. 106, 113701 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee Y., Oh J. Y., Kim T. R., Gu X., Kim Y., Wang G.-J. N., Wu H.-C., Pfattner R., To J. W. F., Katsumata T., Son D., Kang J., Matthews J. R., Niu W., He M., Sinclair R., Cui Y., Tok J. B.-H., Lee T.-W., Bao Z., Deformable organic nanowire field-effect transistors. Adv. Mater. 30, 1704401 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shin M., Song J. H., Lim G.-H., Lim B., Park J.-J., Jeong U., Highly stretchable polymer transistors consisting entirely of stretchable device components. Adv. Mater. 26, 3706–3711 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cho J. H., Lee J., Xia Y., Kim B., He Y., Renn M. J., Lodge T. P., Frisbie C. D., Printable ion-gel gate dielectrics for low-voltage polymer thin-film transistors on plastic. Nat. Mater. 7, 900–906 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Min S.-Y., Kim T.-S., Kim B. J., Cho H., Noh Y.-Y., Yang H., Cho J. H., Lee T.-W., Large-scale organic nanowire lithography and electronics. Nat. Commun. 4, 1773 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walters B. J., Hallengren J. J., Theile C. S., Ploegh H. L., Wilson S. M., Dobrunz L. E., A catalytic independent function of the deubiquitinating enzyme USP14 regulates hippocampal synaptic short-term plasticity and vesicle number. J. Physiol. 592, 571–586 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abbott L. F., Regehr W. G., Synaptic computation. Nature 431, 796–803 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shrotriya V., Li G., Yao Y., Moriarty T., Emery K., Yang Y., Accurate masurement and caracterization of organic solar cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 16, 2016–2023 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Head S. I., Arber M. B., An active learning mammalian skeletal muscle lab demonstrating contractile and kinetic properties of fast- and slow-twitch muscle. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 37, 405–414 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cleworth D., Edman K. A. P., Laser diffraction studies on single skeletal muscle fibers. Science 163, 296–298 (1969). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/4/11/eaat7387/DC1

Additional supporting information

Fig. S1. Working mechanism of s-ONWST.

Fig. S2. Fabrication and morphology of ONW.

Fig. S3. Electrical characteristics of s-ONWST.

Fig. S4. SFDP of s-ONWST.

Fig. S5. Current density-voltage (J-V) characteristics of organic photodetector.

Fig. S6. Output characteristics of the photodetectors with different light spike frequency.

Fig. S7. Frequency-dependent biological muscle contraction and EPSCs of s-ONWST.

Fig. S8. A novel optical wireless communication method of human-machine interface.

Fig. S9. Correlation between EPSC amplitude response and the International Morse code of English letters.

Fig. S10. Full circuit diagram of transimpedance circuit.

Fig. S11. Operating voltage shift of s-ONWST to connect the transimpedance circuit.

Table S1. Summary of electrical characteristics of s-ONWST as function of strain in channel length and width directions.

Table S2. Summary of electrical characteristics of s-ONWST after stretching cycles at 100% strain in channel length and width directions.

Table S3. Maximum δ of polymer actuator and output voltage generated by s-ONWST according to the number of light spikes.

Movie S1. Operation of an artificial muscle actuator by an optical sensory neuromuscular electronic system.