Abstract

Down syndrome (DS) predisposes individuals to early Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Using [11C]PiB, a pattern of striatal amyloid-beta (Aβ) that is elevated relative to neocortical binding has been reported, similar to that of non-demented autosomal dominant AD mutation carriers. However, it is not known if changes in striatal and neocortical [11C]PiB retention differ over time in a non-demented DS population when compared to changes in a non-demented elderly (NDE) population. The purpose of this work was to assess longitudinal changes in trajectories of Aβ in a non-demented DS compared to an NDE cohort. The regional trajectories for anterior ventral striatum (AVS), frontal cortex (FRC) and precuneus (PRC) [11C]PiB retention were explored over time using linear mixed effects models with fixed effects of time, cohort and time-by-cohort interactions and subject as random effects. Significant differences between DS and NDE cohort trajectories for all three ROIs were observed (p<0.05), with the DS cohort showing a faster accumulation in AVS and slower accumulation in FRC and PRC compared to the NDE cohort. These data add to the previously reported distinct pattern of early striatal deposition not commonly seen in sporadic AD by demonstrationg that individuals with DS may also accumulate Aβ at a rate faster in AVS when compared to NDE subjects.

Keywords: Down syndrome, Amyloid, Alzheimer’s disease

1. Introduction

Definitive diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) relies on the demonstration of amyloid-beta (Aβ) plaques and neurofibrillary tangles at autopsy(Hyman et al., 2012). The time course and cause of Aβ deposition in AD remains unclear but two main hypotheses are currently proposed: 1) impaired clearance, like that observed in later-life Aβ deposition seen in preclinical AD, Mild Cognitive Impairment and late-onset AD (Mawuenyega et al., 2010); and 2) altered processing or overproduction of amyloid precursor protein (APP), like that observed in autosomal dominant AD or Down syndrome (DS) (Scheuner et al., 1996). From a large body of data, it is clear that overproduction or altered enzymatic processing of APP are associated with a high risk of AD in autosomal dominant AD and DS and the appearance of clinical AD at an earlier age (Head et al., 2016; Price and Sisodia, 1998).

Aβ PET studies in autosomal dominant AD (ADAD) and DS have identified a distinct pattern of early striatal deposition not commonly seen in late-onset AD (Handen et al., 2012; Klunk et al., 2007), which was confirmed in an autopsy study of ADAD (Shinohara et al., 2014) and DS (Braak and Braak, 1990; Mann and Iwatsubo, 1996). While significant Aβ deposition is observed in an age- and APOEe4-dependent fashion in some non-demented elderly (NDE), a similar pattern of early striatal Aβ is not observed in NDE (Aizenstein et al., 2008) and, in fact, it has been recently suggested that Aβ deposition in neocortex precedes that of striatum in NDE (Hanseeuw et al.). We have previously demonstrated significant differences in striatal PiB retention between NDE and non-demented DS subjects (Cohen et al., 2018) and these data would suggest differences in rates of striatal and neocortical Aβ deposition between non-demented DS and NDE, there is no longitudinal data to directly support this hypothesis.

Therefore, we evaluated the longitudinal rates in early Aβ deposition in a nondemented DS population when compared to rates in an NDE population. We compared the regional trajectories over time for three regions: 1) anterior ventral striatum (AVS), 2) frontal cortex (FRC) and 3) precuneus (PRC), chosen a priori based on areas of known early Aβ deposition from previous studies of DS and NDE (Aizenstein et al., 2008; Handen et al., 2012; Hanseeuw et al.). It was hypothesized that a DS population would differ significantly from an NDE population in terms trajectory rates of Aβ deposition in AVS and neocortical brain regions.

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects

2.1.1. DS Cohort

A total of 83 adults with confirmed DS were recruited from two sites, University of Wisconsin-Madison and University of Pittsburgh, as previously described (Lao et al., 2016). Briefly, exclusion criteria included having a prior diagnosis of dementia, conditions that might contraindicate magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (e.g., claustrophobia, metal in the body), and having a medical or psychiatric condition that impaired cognitive functioning. Participants were assessed for dementia using the Down syndrome Dementia Scale (DSDS) (Gedye, 1995). Three individuals who received a Cognitive Cut-off Score (CCS)>3 (indicating dementia) were removed from this analysis. One individual had a CCS of 3 at entry, but was included based on low Early and Middle Tally score on the DSDS, suggesting dementia was not present. Thus, 80 subjects underwent the image processing described below. All study procedures were approved by the the University of Pittsburgh and the University of Wisconsin- Madison Institutional Review Boards.

2.1.2. NDE cohort

Ninety-eight individuals recruited from the University of Pittsburgh for a longitudinal study of cognitively normal adults (NA) were included in this work. Inclusion criteria were normal cognition and age 65 years or older. Normal cognition was classified according to consensus cognitive diagnosis, which closely follows the approach and structure Alzheimer’s Disease Research center (ADRC) Consensus Conference (Lopez et al., 2000). Exclusion criteria included contraindications for neuroimaging, and history of neurologic, psychiatric, or other medical conditions or treatment associated with potentially significant cognitive symptoms. All participants provided written informed consent and all study procedures were approved by the institutional review board of the University of Pittsburgh.

2.2. Image Acquisition

2.2.1. DS study

PET Scans:

Approximately 15 mCi of Pittsburgh Compound B ([11C]PiB) was delivered intravenously as a slow bolus injection (over 20–30 sec) in the antecubital vein. [11C]PiB PET data were acquired on Siemens ECAT HR+ PET scanners at both sites. A 68Ge/68Ga transmission scan was acquired for 6–10min to correct for photon attenuation, followed by a 20-minute emission scan (4×5-minute frames) beginning 50 minutes after injection. Standard data corrections were applied including those for detector dead time, scanner normalization, scatter, and radioactive decay. Dynamic PET data were reconstructed using a filtered back-projection algorithm (Direct Inverse Fourier Transform [DIFT]) into a 128×128×63 matrix with voxel sizes of 2.06×2.06×2.43 mm3. Images were filtered with a 3mm Hann window.

MRI Scans:

T1-weighted MRIs were acquired on a 3T GE SIGNA 750 at the University of Wisconsin-Madison site and on a 3T Siemens Magnetom Trio at the University of Pittsburgh site. The SIGNA 750 acquisition used high resolution volumetric spoiled gradient sequence (TI/TE/TR=450/3.2/8.2ms, flip angle=12°, slice thickness=1mm no gap, matrix size=256×256×156), while the Magnetom Trio acquisition used a magnetization prepared rapid acquisition gradient echo (MPRAGE) sequence (TI/TE/TR=900/2.98/2300ms, flip angle=9°, slice thickness=1.2 mm, matrix size=160×240×256).

2.2.2. NDE study

PET Scans:

[11C]PiB scans were acquired at the University of Pittsburgh on a Siemens ECAT HR+ scanner as described above.

MRI Scans:

MRI data were collected at the University of Pittsburgh on a 3T Siemens Magnetom Trio scanner as described above.

2.3. Image Processing

MRI and [11C]PiB PET images were processed as previously described (Cohen 2009, Rosario 2011). Dynamic PET images were visually assessed for frame-to-frame motion by generating a whole brain contour on a mid-time point frame in ROITool software (CTI PET Systems Knoxville, TN, USA) and inspecting this contour across all other frames. If interframe motion was observed, a set of stable frames was averaged and used as reference for frame-to-frame registration as previously described (Price et al., 2005). PET data were then averaged over 50–70 min post-injection. MRI images were manually skull-stripped and reoriented so that axial image planes were parallel to the anteriorposterior commissure line. [11C]PiB images were registered to skull-stripped MRIs using rigid body registration in AIR version 3.0, and MRIs were resliced to PET resolution.

Manual region of interest (ROI) drawing was performed on skull-stripped MRIs in PET resolution using ROITool software (Siemens Medical Systems, Knoxville, TN, USA). ROIs drawn included the anterior ventral striatum (AVS), frontal cortex (FRC), precuneus (PRC), and cerebellar grey matter (CER). Standardized uptake value ratios (SUVR) were calculated for the AVS, FRC, and PRC using CER as reference.

2.3. Statistical methods

Descriptive statistics such as mean and standard deviation are presented for age and frequency percentages for sex and APOEe4 allele status (Table 1). Also, means and standard deviations were computed for each cohort and time assesment for the continuous outcomes (AVS, FRC and PRC) (Table 2). It is important to note that the decreasing number of participants over time is not due to attrition but rather the continuing enrollment of new participants in both studies, creating more participants with baseline and Time 2 data, than partipants with data at later timepoints. In Table 2, for descriptive purposes, data is presented as five time points that ranged ± 6 months for each of the 5 time assessments. We refer to baseline or time 0 as first measurement, time 2 as second measurement that was assessed at 24 months± 6, time 3 as 3rd measurement at 36 months± 6, time 4 was 48 months± 6, etc. Time was used as continuous variable in our models to account for the fact that subject measurements were not equally spaced between time assessments.

Table 1:

Demographic information for each cohort:

| Down Syndrome (N=80) | Normal Aging (N=98) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Category | Mean (SD) or N (%) | Mean (SD) or N (%) | Test statistic, p-value |

| Age at baseline | 37.2 (6.9) | 73.5 (5.6) | T(176)=−38.88, p<0.0001 | |

| Sex | Female | 38 (47.5%) | 65 (66.3%) | X(1)=6.40, p=0.011 |

| Male | 42 (52.5%) | 33 (33.7%) | ||

| APOEe4 | Negative | 63 (78.8%) | 63 (64.3%) | X(1)=0.70, p=0.402 |

| Positive | 12 (15.0%) | 17 (17.3%) | ||

| Missing | 5 (6.3%) | 18 (18.4%) |

Table 2:

Descriptive statistics for each ROI by cohort for each time point:

| Baseline | Time 2 | Time 3 | Time 4 | Time 5 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | |

| Normal Aging | ||||||||||

| AVS | 98 | 1.34 (0.29) | 71 | 1.39 (0.31) | 17 | 1.36 (0.35) | 32 | 1.46 (0.37) | 12 | 1.50 (0.40) |

| FRC | 98 | 1.39 (0.32) | 71 | 1.48 (0.35) | 17 | 1.50 (0.42) | 32 | 1.58 (0.41) | 12 | 1.58 (0.44) |

| PRC | 98 | 1.41 (0.35) | 71 | 1.51 (0.39) | 17 | 1.61 (0.54) | 32 | 1.60 (0.42) | 12 | 1.62 (0.44) |

| Down Syndrome | ||||||||||

| AVS | 80 | 1.45 (0.50) | 14 | 1.42 (0.58) | 31 | 1.60 (0.62) | 10 | 1.54 (0.33) | 14 | 1.68 (0.74) |

| FRC | 80 | 1.26 (0.27) | 14 | 1.28 (0.38) | 31 | 1.31 (0.33) | 10 | 1.23 (0.16) | 14 | 1.43 (0.58) |

| PRC | 80 | 1.37 (0.30) | 14 | 1.40 (0.44) | 31 | 1.42 (0.35) | 10 | 1.37 (0.19) | 14 | 1.52 (0.54) |

Data is presented as mean (standard deviation).

To assess the differences in the trajectories of Aβ deposition over time between the NDE and DS cohort, for each of the three ROI’s SUVR a repeated measures model was used. The model was fit for each ROI separately. Best fits were determined via Wald t-tests for the fixed effects and by minimizing the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) for determining the best fitting random effects parameters. The fixed effect parameters were included if the Wald t-tests had p-values ≤ 0.05. Each of the best models included a fixed factor of cohort, a fixed effect of time, age at baseline as well as a fixed interaction term between time and cohort, cohort and age, and a random intercept and slope to account for within-subject correlation. The interaction effect between time and cohort was used to explore the differences in the Aβ trajectories between the DS and NDE cohorts and the interaction term between cohort and age was used to explore the differences between the two groups with respect to age. The Kenward-Rogers method (Kenward and Roger, 1997) was used for computing the degrees of freedom. The following statistical model was fit for each ROI SUVR (y):

where:

β0 represents the intercept (average SUVR value for the reference group (NA) at baseline);

Cohorti is the dummy variable for cohort factor for subject Cohorti =1 if cohort is DS, 0 if NA;

Timeij represents the effect of time, fitted as continuous;

Agei represents age for subject i at baseline;

V0i is the subject-specific variation from average intercept effect, and V1i is the subject specific variation from the average slope with the following variance/covariance matrix: and is the random error term at the jth time point for subject i.

The term β3 represents the difference in the trajectories over time between DS and NDE cohorts, the term β5 represents the age difference between the cohorts and the β2 and β1 represents the estimates of main effects of cohort and time.

3. Results

Mean ages at baseline were 37.2 for the DS (minimum age was 30 years old and maximum was 53) and 73.5 for the NDE (minimum age of 65 and maximum of 88 yeasr old) cohorts, respectively (Table 1). There were significant differences in terms of age between the 2 cohorts (Table 1, p<0.0001). The DS cohort had a nearly equal proportions of males and females, whereas the NDE cohort had more female subjects. There were significant differences with respect to the proportion of males and females between the 2 cohorts (Table 1, p=0.006), however when we tested the addition of the variable sex in the model, it was not significant. There was a comparable incidence of APOEe4 positivity between the DS (12/75 subjects, or 16%) and NDE cohorts (17/80 subjects, or 22%) for whom data on APOEe4 status was available (Table 1). There were no statistically significant differences with respect to APOEe4 between the cohorts.

The baseline SUVR AVS value (starting point) was computed by substituting the parameters from Table 3 into the statistical model equation above. For an average age NDE subject (73.5 years) the baseline SUVR AVS is 1.328 (0.813+0.007*73.5), while the baseline SUVR AVS for an average age DS subject (37.2 years) is equal to 1.450 (0.813 – 1.038+0.007×37.2+ 0.038×37.2).

Table 3:

Repeated measures analysis estimates adjusted for age at entry:

| Effect | β (SE) | t (DF) | p-value | 95% CI for β |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AVS | ||||

| Intercept | 0.813 (0.448) | 1.801(175) | <0.0001 | (−0.071, 1.697) |

| Cohort | −1.037 (0.494) | −2.10 (175) | 0.037 | (−2.013, −0.062) |

| Time | 0.025 (0.006) | 4.09 (112) | <0.0001 | (0.013, 0.038) |

| Time X Cohort | 0.025 (0.009) | 2.63 (120) | 0.009 | (0.006, 0.044) |

| Age | 0.007 (0.006) | 1.18 (175) | 0.238 | (−0.004, 0.019) |

| Age × Cohort | 0.040 (0.008) | 4.62 (176) | <0.0001 | (0.022, 0.054) |

| FRC | ||||

| Intercept | 0.746 (0.366) | 2.04 (178) | 0.043 | (0.023, 1.470) |

| Cohort | −0.330 (0.404) | −0.82 (179) | 0.416 | (−1.127, 0.468) |

| Time | 0.046 (0.006) | 8.21 (112) | <0.0001 | (0.035, 0.057) |

| Time × Cohort | −0.020 (0.008) | −2.29 (120) | 0.024 | (−0.037, −0.003) |

| Age | 0.009 (0.005) | 1.74 (178) | 0.083 | (−0.001, 0.018) |

| Age × Cohort | 0.014 (0.007) | 2.06 (180) | 0.040 | (0.001, 0.027) |

| PRC | ||||

| Intercept | 0.782 (0.406) | 1.92 (177) | 0.057 | (−0.020, 1.584) |

| Cohort | −0.322 (0.446) | −0.72 (178) | 0.507 | (−1.82, 0.587) |

| Time | 0.049 (0.006) | 8.44 (117) | <0.0001 | (0.037, 0.060) |

| Time × Cohort | −0.018 (0.006) | −2.05 (125) | 0.049 | (−0.035, −0.0002) |

| Age | 0.009 (0.006) | 1.56 (177) | 0.123 | (−0.002, 0.019) |

| Age × Cohort | 0.016 (0.007) | 2.17 (178) | 0.043 | (0.0004, 0.030) |

The slope for the NDE AVS (the parameter corresponding to the time effect from Table 3) is 0.025 SUVR units while for DS the slope of the AVS is the sum of the parameters corresponding to the time and time x cohort interaction, 0.050 SUVR units (0.025+0.025). The interaction effect between time and cohort was statistically significant (F (1,120)=7.02, p=0.009), Table 3), suggesting that trajectory rates over time are different between the two groups (the DS have a steeper slope equal to 0.050 SUVRs, compared to 0.025SUVRs for the NDE cohort), suggesting faster striatal Aβ deposition over time as compared to the NDE population. Similarly, the interaction effect between age and cohort was also statistically significant (F (1,176)=21.39, p<0.0001), Table 3) suggesting that the relationship between striatal Aβ deposition and age is different between the DS and NDE cohorts.

The FRC SUVR trajectories are distinct from what we observed for the AVS SUVR, starting with a higher intercept value for the FRC SUVR baseline measurement for the NDE, equal to 1.41 and a lower one for the Down syndrome, 1.27, computed as described above for the AVS ROI. The slope for the NDE FRC was 0.046 SUVR units while for the DS FRC was 0.026 SUVR units. For this particular brain area, NDE demonstrated faster accumulation rates over time compared to DS. The interaction effect between cohort and time was statistically significant, (F(1, 120)=5.23, p=0.024)) suggesting that FRC Aβ deposition rates are different between the DS versus the NDE cohorts, with the NDE cohort having faster Aβ deposition over time in the FRC area as compared to DS. Similarly, the interaction effect between age and cohort was also statistically significant (F (1,180)=4.25, p=0.040)) suggesting that the relationship between PRC Aβ deposition and age is different between the DS and NDE. The PRC area of the brain behaved in a very similar matter as the FRC (Table 3).

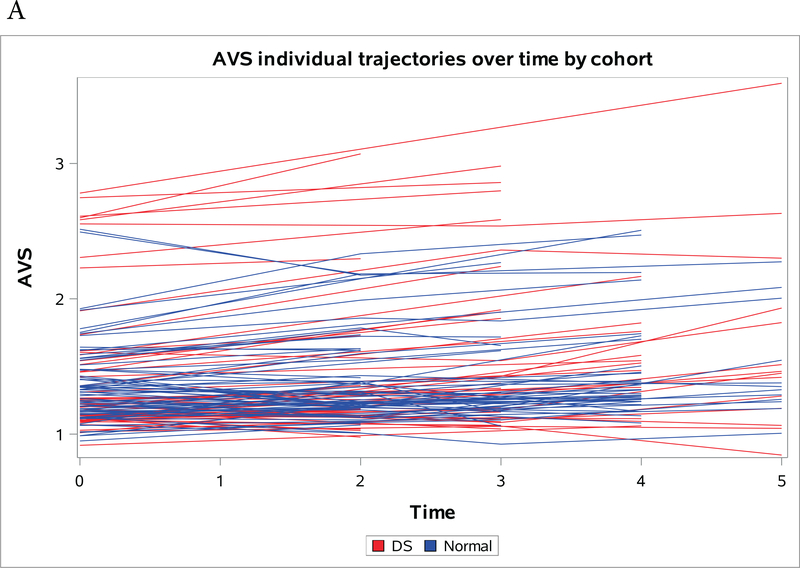

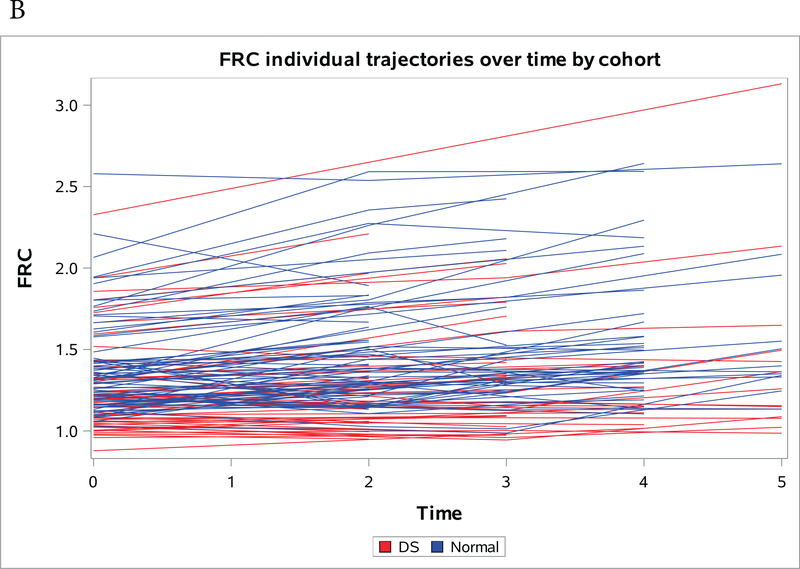

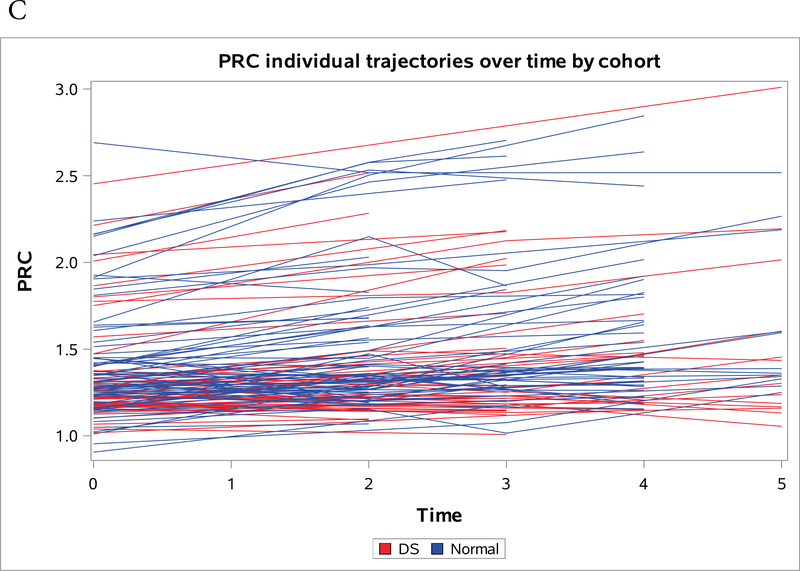

Figures 1a-1c present spaghetti plots of individual trajectories of Aβ deposition values over time for AVS (Figure 1a), FRC (Figure 1b) and PRC (Figure 1c).

Figure 1a-c:

Individual trajectories of change in amyloid over time by region, red denotes NDE and blue denotes DS. (A) Striatum (B) Frontal Cortex (C) Precuneus

4. Discussion

Consistent with our hypothesis, we demonstrated that there were significant differences between DS and NDE cohort Aβ deposition trajectories in the striatum and neocortex. DS and NDE participants differed significantly in longitudinal change in [11C]PiB in both AVS and neocortical ROIs, with faster accumulation of Aβ in DS relative to NDE in AVS and slower accumulation in neocortical regions. This work extends the findings of disproportionately high, early striatal Aβ deposition in DS relative to NDE by exploring the pattern of longitudinal change in Aβ deposition in DS and NDE. These data further highlight the unique characteristic of Aβ deposition that appears to be related to a lifelong alteration of the dynamics of APP production and/or processing in DS (Cohen et al., 2018; Handen et al., 2012; Lao et al., 2016; Lao et al., 2017). Unlike the non-specific retention of many tau-PET ligands in striatum (Pontecorvo et al., 2017) and the nonspecific retention of amyloid-PET ligands in white matter (Rowe et al., 2010; Villemagne et al., 2012), the retention of PiB in striatum specifically represents Abeta deposition (Klunk et al., 2007) that differs from NDE subjects with significant abeta deposition (Cohen et al., 2018). While early striatal predominance in DS has now been well established, to our knowledge this is the first study to demonstrate differences in the longitudinal trajectory of [11C]PiB retention (i.e., Aβ deposition) between individuals with DS and NDE.

The mechanism behind the phenomenon of increased striatal Aβ deposition and accumulation in DS is not well understood. Pathological studies demonstrated increased Aβ−42 relative to Aβ−40 and increased diffuse sub-cortical plaques in DS compared to late onset AD (Fukuoka et al., 1990; Kida et al., 1995; Shinohara et al., 2014). Additionally, it has been demonstrated that Aβ−42 plaques are the first to develop (Lemere et al., 1996). The phenomenon of increased Aβ−42 plaques has also been demonstrated in autosomal dominant AD, which like DS, is associated with overproduction of Aβ and early striatal Aβ predominance (Klunk et al., 2007; Potter et al., 2013). It has been suggested that perhaps the anatomical and Aβ−42 differences observed between genetic disorders associated with overproduction of Aβ (autosomal dominant AD and DS) and disorders of Aβ clearance (late-onset AD) might be due to different processes contributing to plaque development in each disorder (13). In this scenario, late-onset AD is associated more with an increased dependence of APP processing on synaptic activity; thereby increasing the cortical deposition. In autosomal dominant AD or DS, increased Aβ−42 levels might relate to alterations in APP metabolism that result in early increases in APP products. This increased production then eventually overwhelms mechanisms for Aβ clearance (Shinohara et al., 2014). It may be that the production/clearance ratios in DS and autosomal dominant AD are highest in the striatum.

An important consideration in the present study was difference in age between the two groups. The differences in mean age between the two groups is a consequence of the biological question being explored, that is, are there early differences in Aβ accumulation over time between a population known to over-produce Aβ (DS) and one that is believed to have reduced Aβ clearance (NDE). As age is one of the most significant risk factors for Aβ deposition, in both DS (Lao et al., 2016) and normal aging (Jack et al., 2017; Rowe et al., 2010), it was important to consider the relative impact of age on longitudinal change of Aβ. Interestingly, we found a significant cohort x age interaction in each of the regions explored, suggesting that in DS, aging produces a greater relative increase of Aβ in the striatum than in NDE, with the opposite being true in the cortical regions explored (Table 3).

Another consideration in the present study is the use of the cerebellum as a reference region. We acknowledge the findings reported in the literature of improved sensitivity using the white matter reference region within the context of longitudinal studies(Brendel et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2015; Schwarz et al., 2017), particularly related to addressing the shortcomings of technical variability introduced by differences in scanner slice sensitivity and noise. However, we feel strongly that cerebellar grey matter reference region provides a more accurate physiological representation of amyloid burden. Considering the SUVR metric serves as a proxy for the distribution volume ratio (DVR) or binding potential (BPND), the nondisplaceable distribution volume (V_ND = K1/k2’) should be close to equal in these grey matter tissue regions (and thus cancel out in the ratio), and that the overall findings would be expected to be compatible.

A limitation of the present study was the variation in follow-up time between the DS cohort and the NDE cohort. In order to address the differences in follow-up time between the two cohorts, we treated time as a continuous variable in the models to explore the relationship between group and time. However, as can be seen in Table 2, for descriptive purposes, we presented the data as five time points that ranged ± 6 months for each of the 5 timepoints. For instance baseline (or time 0 as presented in the plots) represents the first measurement and time 2 represents the second measurement which was at 24 months± 6, time 3 was 36 months± 6, time 4 was 48 months± 6, etc. Additionally, another limitation of the present study is the small number of participants, particularly in the DS group at the later time points (Table 2). Because of these small group sizes, we are not powered to investigate the effect of APOEe4 on accumulation of Aβ over time.

An important question related to the differences in striatal Aβ predominance in DS (and autosomal dominant AD), is if this phenomenon has any clinical or therapeutic implications. Currently, there are no clear clinical manifestations related to striatal Aβ deposition (e.g., extrapyramidal symptoms), however, a significant association between the striatal [11C]PiB retention and executive cognitive function has been demonstrated in autosomal dominant AD (McDade et al., 2014). It remains to be seen if similar relationships will be detected in DS – although this will be difficult to disentangle from the highly correlated increases in Aβ deposition across all affected brain areas.

What is most striking is the apparent resistance of striatal neurons to very high levels of local Aβ deposition based on the lack of significant striatal atrophy, hypometabolism, or striatal-related behavioral or motor dysfunction in either DS or ADAD. Understanding this cellular resilience could lead to novel therapeutic strategies directed at the protection of neocortical and limbic neurons. Another important consideration is whether the uniquely early striatal Aβ predominance could be used as an early marker in AD treatment trials targeting Aβ in non-demented DS in the future.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

The Down syndrome cohort showed a faster accumulation of amyloid in striatum compared to a not demented elderly cohort.

The Down syndrome cohort showed slower accumulation in cortical regions compared to a not demented elderly cohort.

This is the first report suggesting that individuals with Down syndrome accumulate Aβ at a rate faster in striatum than that seen in not-demented elderly subjects.

Acknowledgements

Supported by The National Institutes of Health grants: P50 AG005133, RF1 AG025516, R01AG031110, U01AG051406.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aizenstein HJ, et al. , 2008. Amyloid deposition is frequent and often is not associated with significant cognitive impairment in the elderly. Archives of Neurology. 65, 1509–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Braak E, 1990. Alzheimer’s disease: striatal amyloid deposits and neurofibrillary changes. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 49, 215–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brendel M, et al. , 2015. Improved longitudinal [(18)F]-AV45 amyloid PET by white matter reference and VOI-based partial volume effect correction. Neuroimage. 108, 450–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, et al. , 2015. Improved power for characterizing longitudinal amyloid-beta PET changes and evaluating amyloid-modifying treatments with a cerebral white matter reference region. J Nucl Med. 56, 560–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AD, et al. , 2018. Early striatal amyloid deposition distinguishes Down syndrome and autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease from late-onset amyloid deposition. Alzheimers Dement. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuoka Y, et al. , 1990. Histopathological studies on senile plaques in brains of patients with Down’s syndrome. Kobe J Med Sci. 36, 153–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gedye, A., 1995. Dementia Scale for Down Syndrome.

- Handen BL, et al. , 2012. Imaging brain amyloid in nondemented young adults with Down syndrome using Pittsburgh compound B. Alzheimers Dement. 8, 496–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanseeuw BJ, et al. , PET STAGING OF AMYLOIDOSIS: EVIDENCE THAT AMYLOID OCCURS FIRST IN NEOCORTEX AND LATER IN STRIATUM. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 12, P20–P21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Head E, et al. , 2016. Aging in Down Syndrome and the Development of Alzheimer’s Disease Neuropathology. Curr Alzheimer Res. 13, 18–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman BT, et al. , 2012. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 8, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR Jr., et al. , 2017. Age-specific and sex-specific prevalence of cerebral betaamyloidosis, tauopathy, and neurodegeneration in cognitively unimpaired individuals aged 50–95 years: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Neurol. 16, 435–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenward MG, Roger JH, 1997. Small sample inference for fixed effects from restricted maximum likelihood. Biometrics. 53, 983–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kida E, et al. , 1995. Early amyloid-beta deposits show different immunoreactivity to the amino- and carboxy-terminal regions of beta-peptide in Alzheimer’s disease and Down’s syndrome brain. Neurosci Lett. 193, 105–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klunk WE, et al. , 2007. Amyloid deposition begins in the striatum of presenilin-1 mutation carriers from two unrelated pedigrees. J Neurosci. 27, 6174–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lao PJ, et al. , 2016. The effects of normal aging on amyloid-beta deposition in nondemented adults with Down syndrome as imaged by carbon 11-labeled Pittsburgh compound B. Alzheimers Dement. 12, 380–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lao PJ, et al. , 2017. Longitudinal changes in amyloid positron emission tomography and volumetric magnetic resonance imaging in the nondemented Down syndrome population. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 9, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemere CA, et al. , 1996. Sequence of Deposition of Heterogeneous AmyloidÎ2-Peptides and APO E in Down Syndrome: Implications for Initial Events in Amyloid Plaque Formation. Neurobiology of Disease. 3, 16–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez OL, et al. , 2000. Research evaluation and diagnosis of probable Alzheimer’s disease over the last two decades. I. Neurology. 55, 1854–1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann DM, Iwatsubo T, 1996. Diffuse plaques in the cerebellum and corpus striatum in Down’s syndrome contain amyloid beta protein (A beta) only in the form of A beta 42(43). Neurodegeneration. 5, 115–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mawuenyega KG, et al. , 2010. Decreased clearance of CNS beta-amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease. Science. 330, 1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDade E, et al. , 2014. Cerebral perfusion alterations and cerebral amyloid in autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 83, 710–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontecorvo MJ, et al. , 2017. Relationships between flortaucipir PET tau binding and amyloid burden, clinical diagnosis, age and cognition. Brain. 140, 748–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter R, et al. , 2013. Increased in Vivo Amyloid-Beta 42 Production, Exchange, and Loss in Presenilin Mutation Carriers. Science Translational Medicine. 5, 189ra77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price DL, Sisodia SS, 1998. Mutant genes in familial Alzheimer’s disease and transgenic models. Annu Rev Neurosci. 21, 479–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price JC, et al. , 2005. Kinetic modeling of amyloid binding in humans using PET imaging and Pittsburgh Compound-B. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 25, 1528–1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe CC, et al. , 2010. Amyloid imaging results from the Australian Imaging, Biomarkers and Lifestyle (AIBL) study of aging. Neurobiol Aging. 31, 1275–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheuner D, et al. , 1996. Secreted amyloid beta-protein similar to that in the senile plaques of Alzheimer’s disease is increased in vivo by the presenilin 1 and 2 and APP mutations linked to familial Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Med. 2, 864–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz CG, et al. , 2017. Optimizing PiB-PET SUVR change-over-time measurement by a large-scale analysis of longitudinal reliability, plausibility, separability, and correlation with MMSE. Neuroimage. 144, 113–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara M, et al. , 2014. Regional distribution of synaptic markers and APP correlate with distinct clinicopathological features in sporadic and familial Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 137, 1533–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villemagne VL, et al. , 2012. Comparison of 11C-PiB and 18F-florbetaben for Abeta imaging in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 39, 983–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.