Abstract

The current generation of left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) provides continuous flow and has the capacity to reduce aortic pulsatility, which may be related to a range of complications associated with these devices. Pulsed LVAD operation using speed modulation presents a mechanism to restore aortic pulsatility and potentially mitigate complications. We sought to investigate the interaction of axial and centrifugal LVADs with the left ventricle (LV) and quantify the effects of continuous and pulsed LVAD operation on LV generated wave patterns under different physiologic conditions using wave intensity analysis (WIA) method. The axial LVAD created greater wave intensity associated with left ventricular relaxation. In both LVADs, there were only minor and variable differences between the continuous and pulsed operation. The response to physiological stress was preserved with LVAD implantation as wave intensity increased marginally with volume loading and significantly with infusion of norepinephrine. Our findings and a new approach of investigating aortic wave patterns based on WIA is expected to provide useful clinical insights to determine the ideal operation of LVADs.

Keywords: Centrifugal blood pump, Axial blood pump, Heart recovery, Suction events, Physiologic artificial heart response, Pulsatility

Introduction

Phasic ejection from cardiac chambers is ubiquitous in nature across phyla1. The clinical indicator of such a pulsatile flow is pulse pressure. Extreme reductions in pulse pressure due to severe aortic stenosis leads to increased shear stress, acquired von Willebrand factor deficiency, and subsequent gastrointestinal bleeding2 related to arteriovenous malformations. On the other hand, high pulse pressure has been implicated in end organ damage as seen in renal failure3, hypertension4, and aortic insufficiency.

The current generation of left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) offers an important option for patients with end-stage heart failure and provides a distinct survival advantage over other therapeutic options5. There are clear benefits of the centrifugal and axial LVADs which are smaller and last longer compared to previous generations of pneumatically driven pulsatile LVADs. However, the reduction in surplus energy with continuous flow relative to pulsatile pumping6 is one potential drawback of these devices and reduced pulse pressure is hypothesized in the causation of gastrointestinal bleeding due to arterio-venous malformation, stroke, thromboembolic phenomena, hemolysis and aortic insufficiency7. Theoretically, pulsed operation of current rotary LVADs could mitigate these adverse events; however, the optimal quantity of pulse pressure needed is not known. Some degree of pulsatility may be potentially restored with speed modulated changes in pump speed8 but this can be accomplished in many ways, whether it be co-pulsation or counter-pulsation and no consensus has been reached regarding the appropriate pulse width or amplitude of speed modulation to produce the greatest hemodynamic benefit.

With the goal of improving clinical care of people with LVADs, wave intensity analysis (WIA)9 has the potential to: 1) inform clinicians of the strength of left ventricular (LV) contraction and relaxation and 2) precisely differentiate between systolic and diastolic dysfunction. Furthermore, WIA can inform the design of future LVADs by quantifying the interactions that occur with the LV throughout the cardiac cycle. WIA is far superior to other methods used to define the amount of pulsatility in the LV or aorta (e.g., pulse pressure, pulse index, energy equivalent pressure10, or surplus hemodynamic energy11) because it quantifies the fundamental energy of waves that create pressure and flow waveforms. One of the major advantages of WIA is that the accurate timing of waves can be measured and related to events that occur throughout the cardiac cycle. WIA has been used extensively to define physiologic aortic wave patterns12–14 and has also been used to investigate intra-aortic balloon pumps15, para-aortic balloon pumps16, and pulsatile LVADs17. However, there have been no reports of using WIA to characterize the LV generated wave patterns caused by continuous flow rotary LVADs, or the use of speed modulation in these devices to create pulsatile flow. Therefore, the aim of this study is to determine the wave intensity patterns created by LVADs and determine the differences between continuous and pulsed operation using speed modulation.

Methods

Experimental Protocol

Details for Animal Preparation, Sugery & Instrumentation, and Dynamic VAD Control are provided in Supplementary information. Continuous operation is defined by setting the LVAD at a constant speed. This signature has natural fluctuations in pump outflow as a result of the regular cyclical changes in pressure difference between inflow and outflow during the cardiac cycle. Pulsed operation was defined by increasing and decreasing the pump impeller speed cyclically with a custom motor controller.

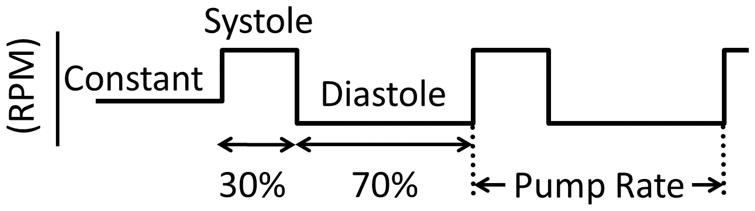

Continuous and pulsed operation are represented in Figure 1 schematically, which shows that pulsed pumping was set to mimic the natural cardiac cycle of systole and diastole by operating faster for 30% of the cycle and slower during the remaining 70%. The pump speeds used during pulsed operation for both the centrifugal and axial LVADs are listed in Table 1. To provide a valid comparison between continuous and pulsed mode, the constant speed set during continuous conditions was designed to be approximately equal to the mean speed during pulsed operation. The rate of pulsed operation was set to be 10% slower than the intrinsic heart rate (as measured during the first 30 seconds of data acquisition). Setting the LVAD to pump asynchronously allowed for the LVAD to pump in phase with the heart (i.e. co-pulsation) and out of phase with the heart (i.e. counter-pulsation). Data were acquired during stable hemodynamic conditions and the LVAD was operated in continuous mode (i.e. constant speed) for 30 seconds and then switched to pulsed operation.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of continuous and pulsed LVAD operation.

The horizontal lines indicate pump speed during continuous (i.e., constant) and pulsed operation (i.e., periods of systole and diastole). The rate of pulsed operation was set to be 10% less than the intrinsic heart rate. RPM: Rotations per minute

Table 1.

Pump speeds during constant and pulsatile pump modes. RPM: Rotations per minute

| Pump Mode | Pump Speed (RPM) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centrifugal 1 | Centrifugal 2 | Axial 1 | Axial 2 | ||

| Continuous | Constant | 2700 | 2700 | 7300 | 7000 |

| Pulsed | Systolic | 3400 | 3400 | 8100 | 7800 |

| Diastolic | 2300 | 2300 | 6800 | 6600 | |

Baseline conditions were measured after the animal reached hemodynamic stability after surgery. Norepinephrine (0.33 – 1.0 μg/kg•min) was used subsequently to increase afterload. After a period of weaning the animal off norepinephrine and a return to baseline conditions, a bolus of approximately 500 mL of Vetastarch (6% hydroxyethyl starch) via a jugular cannula was used to increase preload by raising LV end-diastolic pressure from approximately 5 mmHg (during baseline) to approximately 10 mmHg. This level of volume loading was maintained with further infusions of normal saline. During each intervention (i.e., baseline, increased afterload, and increased preload), pulsed operation of the LVAD was compared to a continuous mode.

Data Analysis

In this study, wave intensity analysis (WIA) was used to calculate the energy associated with waves measured in the ascending aorta.

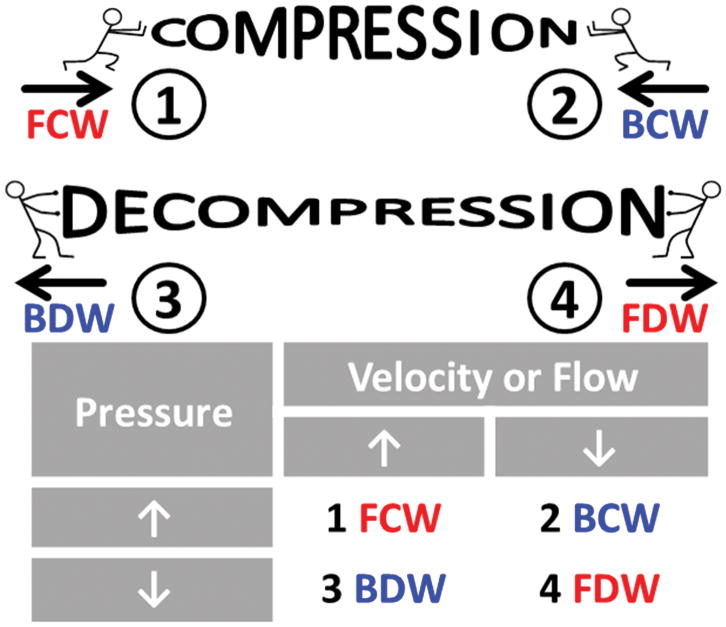

WIA defines four characteristic waves which can be identified by incremental changes in pressure and velocity/flow. Measured at any single location, there are four possible combinations of increasing or decreasing pressure and velocity/flow that allow wave intensity analysis to indicate what type of wave caused these changes, as shown in Figure 2. A forward compression wave (FCW) increases pressure and velocity and a forward decompression wave (FDW) decreases pressure and velocity. A backward compression wave (BCW) increases pressure and decreases flow and a backward decompression wave (BDW) decreased pressure and increases flow. Detailed procedure for WIA is described in Supplementary information.

Figure 2. Wave intensity analysis.

The 4 characteristic waves are: 1) forward compression wave (FCW), 2) backward compression wave (BCW), 3) backward decompression wave (BDW), and 4) forward decompression wave (FDW). Forward-going waves (red font) travel away from the heart and backward-going waves (blue font) travel toward the heart. The table shows the increases (↑) or decreases (↓) of pressure and velocity/flow that are caused by each characteristic wave.

Statistical Methods

Three pump modes (continuous, counter-pulsation, and co-pulsation) were compared using oneway ANOVA (SPSS, version 21). Representative samples from the data were collected by using 30 consecutive cardiac cycles selected from constant speed operation and 30 cardiac cycles selected when the LVAD was in phase (i.e. co-pulsation) and out of phase (i.e. counterpulsation) with the heart (as shown in Figure 4). For all statistical tests, the significance level was set at 0.05 and if the results from one-way ANOVA were significant (i.e. p < 0.05), then multiple comparisons between each group were made with the Bonferroni post-hoc test.

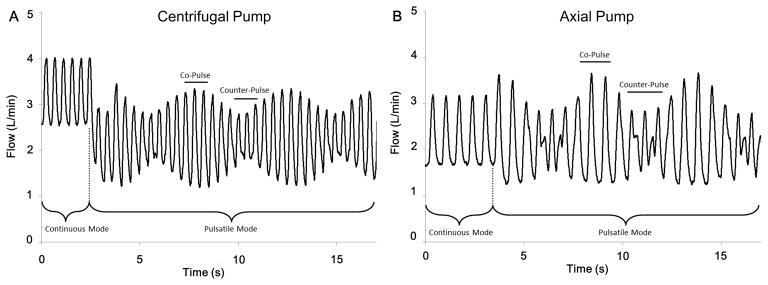

Figure 4. LVAD outflow patterns during continuous flow and asynchronous pulsed operation conditions.

The different LVAD outflow patterns for the centrifugal pump (A) and the axial pump (B) are shown during the transition between continuous and pulsed LVAD operation. The difference between the intrinsic heart rate and LVAD pulse rate result in the amplitude changes of LVAD outflow. Co-pulse is identified by the individual cardiac cycles with high amplitude and counter-pulse is identified by the individual cardiac cycles with low amplitude fluctuations in measured LVAD outflow.

Results

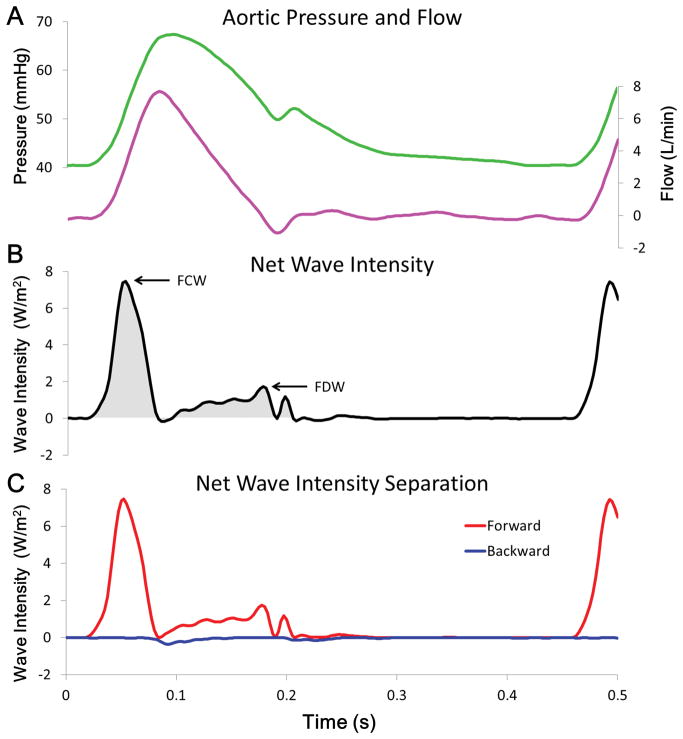

Applying WIA to measurements made in the ascending aorta is shown in Figure 3. The positive net wave intensity throughout the cardiac cycle indicates that forward-going waves (generated by the LV) are the major source of waves measured at this location. The two major hallmark waves, occurring in sequence are: 1) the FCW and 2) the FDW. At the start of the cardiac cycle, net wave intensity increases rapidly to a peak value (~8 W/m2) and the wave can be labeled as a FCW because pressure and flow are increasing. This FCW ends at the zenith of flow and the shaded area underneath the net wave intensity waveform shows the duration of the FCW from start to finish. After the FCW, net wave intensity becomes slightly negative for a few milliseconds, indicating that a backward-going wave is the dominate wave. This backward wave is a BCW (pressure is increasing while flow is decreasing; not labeled) and its weak magnitude has an effect on net wave intensity because the FCW has just ended and the FDW has just started. The FDW begins after the zenith of pressure and it has a slow rise in intensity before reaching a maximum (~2 W/m2) before ending at the same time the dicrotic notch occurs. The last wave that can be identified is another small magnitude FCW (not labeled) that causes pressure and flow to increase for a short period briefly after the dicrotic notch.

Figure 3. Wave intensity analysis of representative waveforms.

(A) Representative pressure (green line) and flow (pink line) waveforms. (B) Calculated net wave intensity (black line), with labels indicating the 2 major waves created by left ventricle (LV); a forward compression wave (FCW) caused by LV contraction and a forward decompression wave (FDW) caused by the start of LV relaxation. The positive magnitude indicating that forward-going waves dominate throughout the cycle. Net positive wave energy is represented by the grey shaded area. (C) Contribution of forward- (red line) and backward-going (blue line) waves, the sum of which equals net wave intensity. Negligible backward waves indicate that the peak values of net wave intensity (i.e. labeled waves) represent the intensity of waves created by the heart.

As net wave intensity is only the sum of forward and backward wave intensity, it is possible that equal magnitude waves cancel each other or a large forward wave disguises smaller but significant backward waves. Determining the decomposition of net wave intensity shown in Figure 3C is made possible by calculating the local wave speed but this requires extra analysis. The important result is that backward-going waves have a minimal impact compared to forward-going waves and net wave intensity (which does not require the extra calculation of wave speed) accurately represents the forward waves created by the LV. The phasic effects of pulsed LVAD operation on measured LVAD outflow are shown in Figure 4, where counter-pulsation causes a decrease and co-pulsation causes an increase of pump flow amplitude.

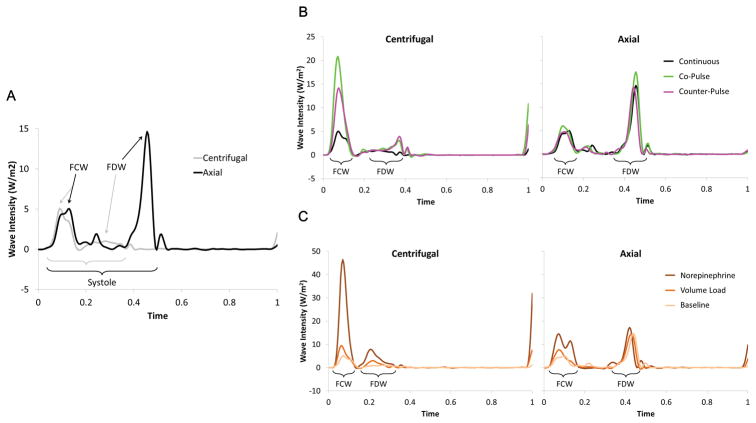

Representative examples of ascending aortic wave intensity for both centrifugal and axial LVADs are shown in Figure 5. Each representative waveform is a single beat that was chosen because it had the smallest mean-squared error compared to an ensemble averaged beat during each pump mode and hemodynamic condition. To account for differences in heart rate between different representative beats, the time axis is normalized to represent a single cardiac cycle.

Figure 5. Representative examples of ascending aortic wave intensity for both centrifugal and axial LVADs.

(A) Comparison of centrifugal and axial pump wave intensity patterns. The net wave intensity for each representative beat is shown during baseline physiologic conditions and continuous LVAD operation. The peak net intensity of the forward compression wave (FCW) and forward decompression wave (FDW) are labeled and the brackets indicate the systolic period of each waveform. The time domain is normalized (0 = start; 1 = end) to compare the different heart rates of each cardiac cycle. (B) Effects of pulsed LVAD operation on wave intensity patterns. The net wave intensity for representative beats is shown during baseline physiologic conditions. Continuous flow, co-pulse, and counter-pulse modes are indicated by the colored lines. The general locations of the forward compression waves (FCW) and forward decompression waves (FDW) are labeled with the brackets. The time domain is normalized (0 = start; 1 = end) to compare the different heart rates of each cardiac cycle. (C) Effects of physiological interventions on wave intensity patterns. The net wave intensity for representative beats is shown during continuous LVAD flow. Each physiologic condition is indicated by the colored lines. The general locations of the forward compression waves (FCW) and forward decompression waves (FDW) are labeled with the brackets. The time domain is normalized (0 = start; 1 = end) to compare the different heart rates of each cardiac cycle.

Tables 2 and 3 summarize basic hemodynamic data when the LVAD was in continuous and pulsed mode during each intervention (i.e., baseline, increased preload, and increased afterload). Average values for systolic, diastolic aortic pressures, and the average heart rate are shown in Table 2, and the cardiac output (i.e., average aortic flow) and LVAD flow (i.e., average pump flow) are shown in Table 3. In general, increasing preload had minimal effect on raising systolic pressure and the decrease in diastolic pressure is likely related to the decreased heart rate that resulted in the volume infusion used to increase preload. Increasing afterload with the infusion of norepinephrine raised both systolic and diastolic pressures and the inotropic effect increased heart rate. The most interesting result shown in Table 3 is the effect that pulsed operation had on the centrifugal pumps. In pulsed mode, the centrifugal pump produced significantly less flow (as illustrated in Figure 4A) and since the total flow provided by the LV and LVAD (i.e., aortic plus pump) was essentially constant, the cardiac output increased when then centrifugal pump was operated in pulsed mode. This pattern was not observed with the axial pump.

Table 2.

Measured aortic blood pressure (BP; units of mmHg and represented as systolic/diastolic) and heart rate (HR; units of beats/minute). All numbers are average values determined by selecting a range of cardiac cycles that correspond to the physiologic interventions (i.e., baseline, increased preload, and increased afterload) and pumping mode (i.e., continuous and pulsed).

| Baseline | Increased Preload | Increased Afterload | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||

| Continuous | Pulsed | Continuous | Pulsed | Continuous | Pulsed | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| BP | HR | BP | HR | BP | HR | BP | HR | BP | HR | BP | HR | ||

|

| |||||||||||||

| Centrifugal | 1 | 63/38 | 136 | 72-35 | 136 | 67/37 | 145 | 77/34 | 146 | 90/44 | 153 | 96/40 | 154 |

| 2 | 69/35 | 96 | 69/27 | 98 | 68/25 | 86 | 72/19 | 77 | 84/41 | 140 | 87/34 | 142 | |

|

|

|||||||||||||

| Axial | 1 | 59/43 | 89 | 50/40 | 89 | 64/38 | 138 | 64/38 | 138 | 73/46 | 149 | 71/45 | 149 |

| 2 | 76/42 | 132 | 76/41 | 132 | 76/28 | 115 | 75/28 | 115 | 86/44 | 149 | 85/43 | 148 | |

Table 3.

Mean aortic flow (i.e., essentially cardiac output) and mean flow provided by the LVAD (units of L/min). All numbers are average values determined by selecting a range of cardiac cycles that correspond to the physiologic interventions (i.e., baseline, increased preload, and increased afterload) and pumping mode (i.e., continuous and pulsed).

| Baseline (flow in L/min) | Increased Preload (flow in L/min) | Increased Afterload (flow in L/min) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||

| Continuous | Pulsed | Continuous | Pulsed | Continuous | Pulsed | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| Aortic | Pump | Aortic | Pump | Aortic | Pump | Aortic | Pump | Aortic | Pump | Aortic | Pump | ||

|

| |||||||||||||

| Centrifugal | 1 | 1.06 | 3.20 | 1.86 | 2.20 | 0.95 | 3.15 | 1.81 | 2.15 | 1.85 | 2.85 | 2.50 | 1.80 |

| 2 | 1.04 | 2.79 | 1.66 | 1.91 | 1.19 | 3.05 | 1.57 | 2.24 | 1.76 | 2.34 | 2.57 | 1.24 | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Axial | 1 | 0.63 | 2.06 | 0.61 | 2.15 | 1.08 | 2.63 | 1.10 | 2.59 | 1.02 | 2.24 | 0.81 | 2.27 |

| 2 | 0.87 | 3.06 | 1.01 | 2.94 | 1.10 | 3.53 | 1.05 | 3.50 | 1.65 | 3.22 | 1.73 | 3.14 | |

Table 4 summarizes the metrics used to measure the waves created by the LV. Data are listed for each experiment and the differences among continuous, co-pulsation, and counter-pulsation are compared during each intervention. In Table 4, the peak intensity of the FCW and FDW that occur at the beginning and end of systole respectively (as labeled in Figure 3B) are shown to provide a measure of how quickly pressure and flow change in response to these waves. Waves can also be quantified by how energetic they are, for example: very intense but short acting waves may carry less energy than less intense but long acting waves (wave energy is shown by the shaded area beneath the waveform shown in Figure 3B). Therefore, Table 4 also displays the energy contributed by all forward-going waves (i.e., FCW plus FDW) to provide a measure of the wave energy provided by the LV under different conditions.

Table 4.

Peak forward compression, decompression wave intensity (units of W/m2), and forward wave energy (units of J/m2). Data are mean values ± standard error of the mean. Statistical results are from one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni comparisons between continuous (C), counter-pulse (CtP), and co-pulse (CoP) within each condition.

| Baseline | Increased Preload | Increased Afterload | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| C | CtP | CoP | C | CtP | CoP | C | CtP | CoP | |||

|

| |||||||||||

| Centrifugal | Peak forward compression wave intensity | 1 | 6.9±0.4 | 18.1±0.6* | 20.8±0.7*† | 11.7±0.6 | 31±0.9* | 33.8±0.6*† | 53.5±1.2 | 82.9±1.0* | 86.3±0.9* |

| 2 | 4.2±0.1 | 6.1±0.1* | 6.4±0.1*† | 28.7±0.3 | 41.6±0.3* | 39.7±0.3*† | 32.6±0.5 | 50.9±0.7* | 51.2±0.3* | ||

|

| |||||||||||

| Peak forward decompression wave intensity | 1 | 1.2±0.0 | 4.1±0.1* | 3.6±0.1*† | 2.5±0.1 | 4.4±0.1* | 4.1±0.0*† | 6.8±0.1 | 7.4±0.1* | 7.6±0.1* | |

| 2 | 3.9±0.1 | 6.3±0.1* | 5.6±0.1*† | 3.4±0.1 | 6.4±0.0* | 5.4±0.1*† | 5.1±0.1 | 11.4±0.2* | 10.2±0.1*† | ||

|

| |||||||||||

| Forward wave energy | 1 | 0.27±0.01 | 0.61±0.01* | 0.66±0.01*† | 0.38±0.01 | 0.86±0.02* | 0.92±0.01*† | 1.24±0.02 | 1.85±0.02* | 1.92±0.02* | |

| 2 | 0.21±0.00 | 0.34±0.00* | 0.34±0.00* | 0.84±0.00 | 1.22±0.01* | 1.15±0.01*† | 0.90±0.01 | 1.34±0.01* | 1.33±0.01* | ||

|

| |||||||||||

| Axial | Peak forward compression wave intensity | 1 | 0.7±0.0 | 0.6±0.0 | 0.7±0.1 | 2.7±0.1 | 2.6±0.1 | 2.9±0.1 | 3.2±0.1 | 1.5±0.0* | 2.4±0.1*† |

| 2 | 5.3±0.2 | 5.4±0.1 | 5.6±0.2 | 8.5±0.1 | 8.2±0.1 | 8.4±0.1 | 15.8±0.4 | 15.8±0.3 | 17.1±0.4*† | ||

|

| |||||||||||

| Peak forward decompression wave intensity | 1 | 4.7±0.1 | 4.7±0.2 | 4.8±0.2 | 3.4±0.1 | 3.6±0.1 | 3.3±0.1 | 4.8±0.1 | 2.9±0.0* | 3.2±0.1*† | |

| 2 | 15.4±0.4 | 15.4±0.4 | 15.3±0.4 | 14.6±0.1 | 15.4±0.2* | 14.8±0.2† | 18.8±0.3 | 19.4±0.4 | 19.2±0.4 | ||

|

| |||||||||||

| Forward wave energy | 1 | 0.18±0.00 | 0.17±0.01 | 0.18±0.01 | 0.19±0.00 | 0.18±0.01 | 0.19±0.00 | 0.22±0.01 | 0.13±0.00* | 0.17±0.00*† | |

| 2 | 0.61±0.01 | 0.61±0.01 | 0.62±0.01 | 0.76±0.00 | 0.77±0.00 | 0.76±0.00† | 0.96±0.01 | 0.97±0.01 | 1.00±0.01 | ||

(p < 0.05) indicates a comparison to continuous and

(p < 0.05) indicates a comparison to counter-pulse.

Discussion

Our findings are as follows: 1) That centrifugal and axial pumps cause fundamentally different aortic wave characteristics. The data show a pattern of axial pumps producing larger FDWs (i.e., LV relaxation) compared to variable FCWs (i.e., LV contraction) and centrifugal pumps producing larger FCWs compared to FDWs. 2) For centrifugal pumps, both co- and counter-pulsation resulted in increases to peak forward wave intensity compared to continuous speed. 3) For axial pumps, there were minimal effects of co- or counter-pulsation compared to continuous speed. 4) Changes in preload and afterload caused increases in wave intensity consistent with existing literature. These findings are important to elucidate the ideal pumping strategy that would allow LV function (as measured by the strength of waves it creates) to be modulated selectively.

Comparative WIA between pump types: centrifugal vs axial pump

LVAD induced ventricular suction increases the risk that ventricular arrhythmias will occur23 and deformational changes to the interventricular septum can alter right ventricular function24. Clinically, the magnitude of the FDW should be related to possible LV suction events and could potentially offer another diagnostic tool to identify and avoid suction events and right ventricular dysfunction over time. The magnitude of the FDW is considered to be an indication of LV function during late systole and isovolumic relaxation20. As shown in Figure 5A, the characteristic wave pattern created by the axial LVAD has a relatively large magnitude FDW (indicating a quick drop in LV pressure and deceleration of aortic flow, which is rarely seen in the literature) which suggests that the axial pump provides greater suction compared to the centrifugal pump design. This behavior would match the expectations of using an axial pump design, as this type of design has been noted to have a greater potential to create ventricular suction compared to a centrifugal pump design22.

Comparative WIA between flow characteristics: continuous vs pulsatile flow

Theoretically, recovery of the LV may be possible if LVADs are implemented earlier in the disease progression and a normal range of pulsatility is restored. In this study, the data show different responses of centrifugal and axial LVADs to pulsed operation. Pulsation appears to increase the intensity of waves consistently with the centrifugal pump, while pulsation had variable and relatively small effects with an axial pump. The behavior of the centrifugal pump may be related to the drop in average flow observed during pulsed operation (Figure 4), implying that the heart produced more work, as the total sum of mean aortic root flow plus mean pump flow did not change.

The strength of forward-going waves created by the LV will indicate if the force of LV contraction is altered during co-pulsation or counterpulsation (Figure 5B). There is evidence that pump speed modulation of continuous flow LVADs will influence the unloading of the LV7 and the amount of energy expended by the LV is related to co- or counter-pulsation of a pulsatile LVAD25. It can be hypothesized that co-pulsation would strengthen the intensity of LV generated waves as the heart is assisted during systole and the Frank-Starling mechanism is engaged with greater filling during diastole. Alternatively, it can be hypothesized that counterpulsation would depress the intensity of LV generated waves as the heart is assisted less during systole and blood volume is diverted during diastole that would otherwise promote a more forceful contraction. The results of this study are inconclusive as there are minimal and inconsistent differences between co-pulsation and counter-pulsation. To prove whether speed modulation of LVADs has the potential to restore natural wave patterns generated by the LV further in vivo testing is necessary.

Limitations

The small number of experimental trials used in this study and the variable responses to pump perturbations (i.e., continuous vs pulsatile flow) and physiologic interventions (i.e., increased preload and afterload) present major limitations to generalizing these results.

Further wave analysis using the excess pressure defined by the reservoir-wave model30, 31 was not performed as the increases in heart rate and the perturbations caused by pulsed pumping did not allow the reservoir pressure to be calculated consistently.

The wave patterns created by the LV were not measured prior to LVAD implantation. This was due to the extreme irritability posed by porcine hearts when handled and any such manipulation would have affected subsequent results. Once the LVAD was implanted, the heart could be manipulated with more ease. Therefore, the major limitation of this study is that changes in the characteristic LV wave pattern before and after LVAD surgery were not measured. Heart function with the LVAD turned off (and the inflow/outflow cannulas clamped) could have been measured but concerns related to the stasis of blood in the pump and the formation of blood clots dictated the decision to not test this option. While the comparisons between the ability of centrifugal and axial pumps to influence LV generated wave patterns are still valid, further studies could be designed to quantify the characteristic wave patterns before and after LVAD implantation.

As shown in Figure 4A the average flow provided by the centrifugal pump in continuous mode decreases when pulsed mode is used to investigate periods of co-pulsation and counter-pulsation (e.g., in Figure 4A from ~3.5 to ~2.25 L/min). This study did not have access to centrifugal pump design specifications that would allow us to generate a testable hypothesis regarding fluid dynamic inefficiencies related to the impeller or housing design to explain this phenomenon. Therefore, this reduction in average flow remains a confounding factor in the specific comparison between continuous to pulsatile mode comparisons with a centrifugal pump. Further study is necessary to confirm this behaviour and validate the difference between wave intensity patterns measured in the centrifugal pump; specifically, the increase in peak FCW intensity that is observed when co-pulse or counter-pulse is compared to continuous mode (i.e., Figure 5B).

The absolute magnitude of the FCWs and FDWs was somewhat variable between the Axial 1 and 2 experiments as shown in Table 4. This is likely a result of each animal responding differently. Despite the fact that waves recorded in Axial 1 are much lower in magnitude, the relative pattern of larger FDWs compared to FCWs still holds and supports the illustration shown in Figure 5.

Clinical implications and limitations of current study are further discussed in Supplementary information.

Conclusions

WIA enabled to quantify waves that can be used to determine which type of pulsed LVAD operation offers the greatest benefit to heart failure patients. Centrifugal and axial pumps interacted with the LV in different and important ways. The starkest difference was that the axial pump design appeared to cause a relatively strong FDW related to ventricular relaxation. This is the first study to show an instance where the wave caused by LV relaxation is relatively greater than the wave caused by LV contraction. Augmenting the ability of the LV to relax could encourage increased coronary blood flow and may help LV recovery. The identification of this characteristic wave pattern is important because it could be used to determine the ideal operation of LVADs and avoid the possibility of suction events and right ventricular dysfunction.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding: The project described was supported by NIH/NHLBI grant# R21HL118611.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: No relationships with industry to report. Part of this work was presented at American Heart Association Scientific Sessions in Anaheim, CA, Nov 2017.

References

- 1.Bishopric NH. Evolution of the heart from bacteria to man. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1047:13–29. doi: 10.1196/annals.1341.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caspar T, Jesel L, Desprez D, et al. Effects of transcutaneous aortic valve implantation on aortic valve disease-related hemostatic disorders involving von Willebrand factor. Can J Cardiol. 2015;31:738–43. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2015.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malone AF, Reddan DN. Pulse pressure. Why is it important? Perit Dial Int. 2010;30:265–8. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2010.00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benetos A, Safar M, Rudnichi A, et al. Pulse pressure: a predictor of long-term cardiovascular mortality in a French male population. Hypertension. 1997;30:1410–5. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.30.6.1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirklin JK, Naftel DC, Pagani FD, et al. Sixth INTERMACS annual report: a 10,000patient database. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33:555–64. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Travis AR, Giridharan GA, Pantalos GM, et al. Vascular pulsatility in patients with a pulsatile- or continuous-flow ventricular assist device. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;133:517–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soucy KG, Koenig SC, Giridharan GA, Sobieski MA, Slaughter MS. Rotary pumps and diminished pulsatility: do we need a pulse? ASAIO J. 2013;59:355–66. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0b013e31829f9bb3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asgari SS, Bonde P. Implantable physiologic controller for left ventricular assist devices with telemetry capability. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;147:192–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parker KH. An introduction to wave intensity analysis. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2009;47:175–188. doi: 10.1007/s11517-009-0439-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shepard RB, Simpson DC, Sharp JF. Energy equivalent pressure. ArchSurg. 1966;93:730–740. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1966.01330050034005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bouwmeester JC, Waters B, Naderiparizi MS, Letzen B, Smith JR, Bonde P. Aortic surplus hemodynamic energy accurately reflects physiological functioning of continuous flow LVADs in an ECG gated operation. 22nd Annual Congress of the International Society for Rotary Blood Pumps; San Francisco, CA. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones CJ, Sugawara M, Kondoh Y, Uchida K, Parker KH. Compression and expansion wavefront travel in canine ascending aortic flow: wave intensity analysis. Heart Vessels. 2002;16:91–98. doi: 10.1007/s003800200002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khir AW, Parker KH. Wave intensity in the ascending aorta: effects of arterial occlusion. J Biomech. 2005;38:647–655. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang JJ, Bouwmeester JC, Belenkie I, Shrive NG, Tyberg JV. Alterations in aortic wave reflection with vasodilation and vasoconstriction in anaesthetized dogs. Can J Cardiol. 2013;29:243–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lu PJ, Yang CF, Wu MY, Hung CH, Chan MY, Hsu TC. Wave energy patterns of counterpulsation: a novel approach with wave intensity analysis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;142:1205–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu PJ, Yang CF, Wu MY, Hung CH, Chan MY, Hsu TC. Wave intensity analysis of para-aortic counterpulsation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H1481–91. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00551.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khir AW, Swalen MJ, Segers P, Verdonck P, Pepper JR. Hemodynamics of a pulsatile left ventricular assist device driven by a counterpulsation pump in a mock circulation. Artif Organs. 2006;30:308–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2006.00218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goodrich JA, Bouwmeester C, Letzen B, Waters B, Smith J, Bonde P. Refinement of an anesthesia protocol fora porcine model for a FREE-D powered ventricular assist device. J Invest Surg. 2015;28:60. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khir AW, O’Brien A, Gibbs JSB, Parker KH. Determination of wave speed and wave separation in the arteries. J Biomech. 2001;34:1145–1155. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(01)00076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohte N, Narita H, Sugawara M, et al. Clinical usefulness of carotid arterial wave intensity in assessing left ventricular systolic and early diastolic performance. Heart Vessels. 2003;18:107–111. doi: 10.1007/s00380-003-0700-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Penny DJ, Mynard JP, Smolich JJ. Aortic wave intensity analysis of ventricular-vascular interaction during incremental dobutamine infusion in adult sheep. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H481–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00962.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giridharan GA, Koenig SC, Soucy KG, et al. Left ventricular volume unloading with axial and centrifugal rotary blood pumps. ASAIO J. 2015;61:292–300. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000000201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vollkron M, Voitl P, Ta J, Wieselthaler G, Schima H. Suction events during left ventricular support and ventricular arrhythmias. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2007;26:819–25. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwarz K, Singh S, Dawson D, Frenneaux MP. Right ventricular function in left ventricular disease: pathophysiology and implications. Heart Lung Circ. 2013;22:507–11. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2013.03.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amacher R, Weber A, Brinks H, et al. Control of ventricular unloading using an electrocardiogram-synchronized Thoratec paracorporeal ventricular assist device. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;146:710–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berne RM, Levy MN. Cardiovascular Physiology. 8. St. Louis: Mosby; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tuttle RR, Mills J. Dobutamine: development of a new catecholamine to selectively increase cardiac contractility. Circ Res. 1975;36:185–96. doi: 10.1161/01.res.36.1.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Belenkie I, Smith ER, Tyberg JV. Ventricular interaction: from bench to bedside. AnnMed. 2001;33:236–241. doi: 10.3109/07853890108998751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moore TD, Frenneaux MP, Sas R, et al. Ventricular interaction and external constraint account for decreased stroke work during volume loading in CHF. AmJPhysiolHeart CircPhysiol. 2001;281:H2385–H2391. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.6.H2385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tyberg JV, Bouwmeester JC, Parker KH, Shrive NG, Wang JJ. The case for the reservoir-wave approach. Int J Cardiol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.12.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang JJ, O’Brien AB, Shrive NG, Parker KH, Tyberg JV. Time-domain representation of ventricular-arterial coupling as a windkessel and wave system. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H1358–H1368. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00175.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.