Abstract

In this case report, we describe a young athletic male with a family history of early sudden cardiac death who presented with atypical chest pain and was found to have a positive serum troponin. Although his symptoms resolved without intervention, workup revealed hypertension, hyperlipidemia, mild left ventricular hypertrophy, non-obstructive coronary artery disease, and the presence of serum heterophile antibodies. Ultimately, it was concluded that his rigorous exercise regimen as well as the presence of heterophile antibodies may have contributed to his positive serum troponin. This case serves as a reminder of the nonspecific diagnostic value of modern troponin assays, and that the results of these tests should always be incorporated into the clinical context.

Keywords: Exercise, False positive, Heterophile antibody, Myocardial ischemia, Troponin

Introduction

Myocardial injury occurs when the integrity of the myocyte membrane is compromised, resulting in leakage of intracellular molecules such as creatine kinase, troponin, and lactate dehydrogenase into the extracellular space [1]. Of these various enzymes and structural proteins, only cardiac troponins are highly specific for myocardial cells [2]. Assays that quantify serum cardiac troponin levels have thus become central to the evaluation of patients with possible acute myocardial infarction (AMI).

Over the last several decades, efforts on the troponin assay have largely focused on increasing test sensitivity to ensure that an AMI is not missed. Modern fifth-generation high-sensitivity cardiac troponin (hs-cTn) tests can detect serum troponin concentrations 100 times lower than conventional assays [3]. Indeed, the negative predictive value of hs-cTn for AMI is greater than 95% at presentation and rises to nearly 100% if repeat testing is performed within 3–6 h [4].

However, with the increased sensitivity of modern troponin assays, elevated levels are frequently discovered in a variety of situations apart from AMI [5]. Recognizing if troponin elevations are due to AMI versus another mechanism has important implications for clinical management. In this report, we present an athletic young male whose troponin was positive in the presence of serum heterophile antibodies. Informed consent was obtained from the patient for being included in this case report.

Patient Presentation

A 27-year-old Asian male presented to the emergency department with 1 day of intermittent chest discomfort. During his morning routine, he noticed mild substernal chest pressure lasting a few seconds. While at work, the same sensation returned and continued for a few seconds every 15 min. The discomfort was not associated with activity, jaw or arm discomfort, shortness of breath, palpitations, nausea, diaphoresis, or lightheadedness. There was no history of trauma. Notably, the patient was training for a marathon and ran 3 miles the day before. He had no past medical history, was a non-smoker, and took no medications, illicit drugs, or dietary supplements. Family history was notable for sudden cardiac death in his father at age 40.

Clinical Findings

Initial vital signs were notable for blood pressure of 147/84 mmHg. A complete physical exam and electrocardiogram (ECG) were unremarkable (Fig. 1). Laboratory testing revealed a positive troponin I of 0.123 ng/ml (normal < 0.055 ng/ml) and dyslipidemia with fasting total cholesterol 235 mg/dl, direct low-density lipoprotein (LDL) 170 mg/dl, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) 38 mg/dl, and triglycerides 124 mg/dl. Urine toxicology was unremarkable. His chest pressure resolved in the emergency department without intervention and he was admitted for further work-up. Echocardiography showed normal biventricular function and no valvular abnormalities. Computed tomography coronary angiography (CCTA) showed mild, non-obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD) in the left anterior descending artery (Fig. 2). Serial troponin I measurements were persistently positive (peaking at 0.124 ng/ml) throughout the next day, despite no further episodes of chest pressure. Telemetry monitoring was unremarkable and there were no significant changes to serial ECGs throughout his hospitalization. He was discharged the following day with plans for outpatient follow-up.

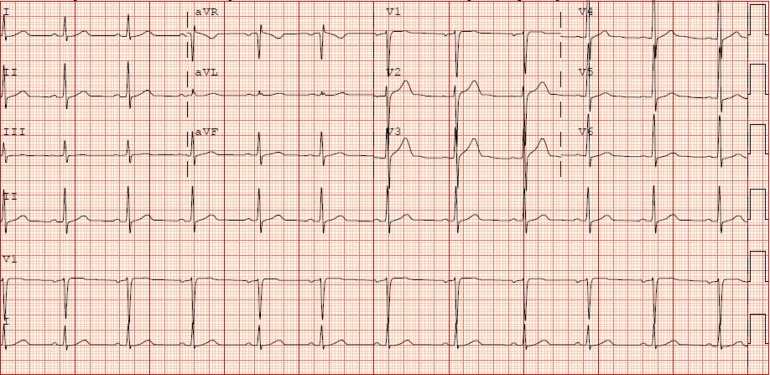

Fig. 1.

ECG on presentation showed sinus rhythm at 66 beats per minute, with normal axis and intervals. There were no ST or T-wave changes

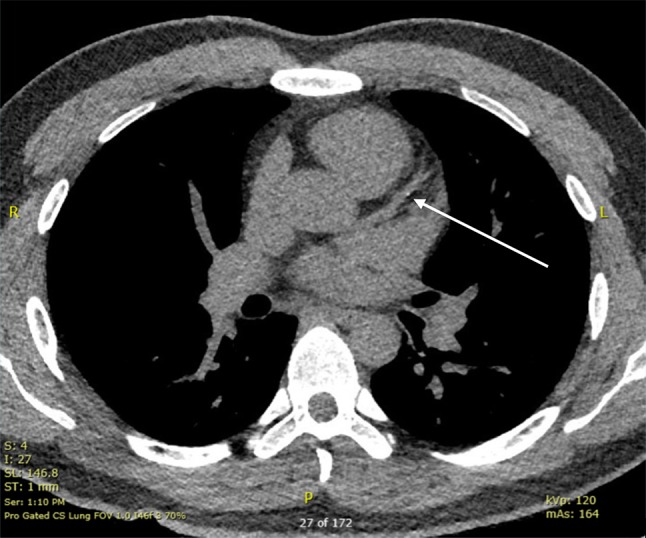

Fig. 2.

CCTA showed mild non-obstructive CAD in the left anterior descending artery as labeled

Two months later he was seen in cardiology clinic to establish care, where he was asymptomatic and reported that he was still training for a marathon. A repeat ECG was similar to the prior one. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (cMRI) showed normal biventricular function without late gadolinium enhancement suggestive of infiltrative disease, myocarditis, or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (Fig. 3). Laboratory testing at this time revealed a serum troponin I of 0.213 ng/ml and total creatine kinase (CK) of 453 U/l (normal < 300 U/l), though creatine kinase-muscle/brain (CK-MB) was only 1.5 ng/ml and relative index was 0.3%. He was started on aspirin (81 mg daily) and rosuvastatin (20 mg daily) and instructed to refrain from exercise for 1 week. Laboratory testing at the end of an exercise-free week showed troponin I and CK within normal limits, as well as an improved lipid profile (total cholesterol 123 mg/dl, LDL 72 mg/dl, HDL 38 mg/dl, triglycerides 67 mg/dl). Follow-up testing of the serum sample from the initial clinic visit revealed the presence of a heterophile antibody.

Timeline of events

| Time | Events |

|---|---|

| Prior to November 2017 | The patient participated in moderate to intense aerobic activity several times per week |

| November 2017: Day 1 | He presented with chest pressure to the emergency room and was found to have an elevated serum troponin I of 0.123 ng/ml and evidence of dyslipidemia with a fasting total cholesterol 235 mg/dl, direct LDL 170 mg/dl, HDL 38 mg/dl, and triglycerides 124 mg/dl. These findings, in conjunction with a family history of sudden cardiac death, led to an admission to the cardiology service for further evaluation |

| Day 2 | CCTA showed mild, non-obstructive CAD in the left anterior descending artery. TTE showed mild LVH. Telemetry and serial ECG monitoring was unremarkable. The patient’s chest pressure resolved and he was discharged from the hospital |

| December 2017 through January 2018 | The patient continued to participate in aerobic activity multiple times per week |

| Late January 2018 | The patient presented for follow-up in clinic and was asymptomatic. Repeat laboratory values showed a serum troponin I level of 0.213 ng/ml, CK of 453 U/l (normal < 300 U/l). cMRI was unremarkable. He was started on aspirin (81 mg daily) and rosuvastatin (20 mg daily) and instructed to refrain from exercise until the next clinic visit in 1 week |

| Early February 2018 | The patient presented to his second clinic visit and was again asymptomatic. Testing on serum from the prior clinic visit revealed the presence of a heterophile antibody. Repeat testing of his serum showed an improved lipid profile and a negative troponin I |

Fig. 3.

cMRI did not show any abnormalities

Discussion

In this report, we describe the case of a young athletic male with hyperlipidemia and family history of early cardiac death, who presented with atypical chest pain and an elevated serum troponin. The initial differential diagnosis was broad and reflected the common causes of troponinemia.

In addition to acute coronary syndromes (ACS), cardiac troponin elevations above a 99th percentile cutoff occur in many conditions (Table 1). In most cases, myocyte necrosis occurs from either mismatch between oxygen supply and demand within the heart or direct injury from trauma or toxins [6–11]. Impaired renal clearance also contributes to troponin elevation despite the lack of detectability in urine [10]. Lastly, analytical errors in the assay and interfering substances such as heterophile antibodies from a patient’s serum can lead to elevated measured troponins that do not reflect myocardial injury (i.e., “false positives”) [12].

Table 1.

Causes of serum cardiac troponin elevations including false-positive troponinemia

| Ischemic | Non-ischemic | False-positive troponin | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac | Acute coronary syndrome | Myocarditis/pericarditis | High alkaline phosphatase levels |

| Oxygen supply/demand mismatch | Infectious | Heterophile antibody | |

| Hypertension | Non-infectious/autoimmune | Troponin-specific autoantibody | |

| Tachycardia/arrhythmia | Infiltrative disease | Rheumatoid factor | |

| Anemia | Trauma (cardiac contusion) | Fibrin clots | |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | Electric shock (cardioversion) | Endogenous substances | |

| Drugs (cocaine, methamphetamines) | Ablation procedures | Hemoglobin, bilirubin, lipids | |

| Non-atherosclerotic coronary disease | Congestive heart failure | Biotin | |

| Coronary vasospasm | Drug-induced (trastuzumab, anthracyclines) | Instrument malfunction | |

| Coronary embolus | Machine calibration error | ||

| Coronary artery vasculitis | |||

| Aortic dissection | |||

| Post-revascularization | |||

| Non-cardiac | Pulmonary embolism | Renal failure | |

| Sepsis/shock/hypoperfusion | Stroke/intracranial hemorrhage | ||

| Hypoxia | Significant burns | ||

| Critical illness | |||

| Cardiothoracic surgery |

In this patient’s workup, ACS was deemed as an unlikely cause for this patient’s troponinemia given the atypical nature of his symptoms, the lack of any ischemic changes on ECG, and the lack of a significant change in the serum troponin level on serial measurements during his hospital stay [13]. In addition, obstructive coronary disease was excluded with CCTA. Acute pulmonary embolism was briefly entertained but was not formally evaluated with CT angiography due to extremely low pre-test probability (WELLS score of 0). Echocardiography did show evidence of mild LVH, but his normal cMRI likely excluded hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and additionally excluded myocarditis and infiltrative disease. Importantly, however, with the history of his father’s early sudden cardiac death, combined with his premature non-obstructive coronary disease and elevated serum LDL, the patient meets criteria for possible familial hypercholesterolemia by the Dutch Lipid Clinic Network [14].

After the work-up, two diagnoses seemed plausible: heterophile antibody mediated false-positive troponinemia and/or exercise-mediated troponinemia. The presence of heterophile antibody in his serum suggested that his troponin assay might have been falsely positive. On the other hand, his serum troponin seemed to be elevated only in the context of rigorous aerobic exercise, and normalized when he refrained from activity.

Heterophile antibodies are among the many substances that can potentially interfere with a troponin assay (Table 1). These antibodies are produced against poorly defined antigens, weakly bind with immunoglobulins from two or more non-human animal species, and can act like a rheumatoid factor (bind to the Fc portion of human immunoglobulin) [15]. Their multi-specific binding potential can crosslink assay antibodies in the absence of the antigen of interest, causing inconsistent false-positive results. Test manufacturers typically add blocking antibodies to reduce the chance of interference, but a high serum concentration of heterophile antibody may overcome this protection (which was the case in our patient) [16]. While a dynamic rise and/or fall in troponin levels in the appropriate clinical setting suggests true myocardial damage, a sustained, relatively fixed increase in troponin levels in the absence of other evidence of cardiac injury raises the likelihood of assay false-positivity [13].

In contrast to the benign implication of heterophile antibody-mediated troponinemia, the prognosis of exercise-mediated troponinemia remains unclear. Many studies report rises in cardiac troponin levels after exercise [17, 18], while others have published a lack of this relationship [19, 20]. A meta-analysis examining 26 studies on exercise and troponin levels found that post-exercise levels rose above the lower limit of detection in approximately 50% of subjects, with higher likelihoods of positivity after running events (as opposed to cycling or a triathlon) and with shorter events (rather than longer events), suggesting a correlation with higher intensity exercise [21]. In marathon runners, troponin can be detected as early as 60 min into exercise and as late as 24 h from the event [22]. Imaging studies suggest against a correlation between post-exercise troponin elevation and radiographic evidence of permanent myocardial damage, but long-term data examining this question are sparse [23]. Moreover, recent data published by Roos et al. suggest that patients with chest pain and elevated troponin not due to myocardial infarction or other causes are at increased risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality [24]. In light of this evidence, and in conjunction with a family history of sudden cardiac death and possible familial hyperlipidemia, this patient’s troponinemia should not be prematurely dismissed as benign, regardless of the presence of a serum heterophile antibody.

Conclusions

This case serves as an important reminder regarding the adjunctive value of laboratory testing to clinical judgment. Although cardiac troponins are highly sensitive and specific for myocardial injury, serum levels rise in numerous conditions apart from AMI. Thus, their utility as a diagnostic tool for acute coronary syndromes largely depends on the history and careful interpretation of the ECG. Hasty interpretation of a positive serum troponin can lead to inappropriate and potentially harmful management. This case additionally highlights the possibility of a false-positive troponin assay result due to the presence of serum heterophile antibodies or troponinemia from vigorous physical activity. Ultimately, all patients with positive serum troponins should undergo a thorough evaluation for a mechanism of myocardial injury. In those patients whose workup is unrevealing, clinicians should keep in mind the possibility of interfering substances in the assay.

Management

The patient was started on high-intensity rosuvastatin (20 mg daily) and low-dose aspirin (81 mg daily) therapies to treat his hyperlipidemia and non-obstructive CAD. Follow-up lipid panel testing showed an excellent reduction in serum LDL levels. He has not had recurrence of anginal symptoms and continues to exercise regularly. He will require ongoing follow-up for aggressive primary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Raffick Bowen, Ph.D., MHA, MLT, for his assistance with the interpretation of laboratory results described in this case report.

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility of the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Lakshman Manjunath, Apurva Yeluru, and Fatima Rodriguez have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Written informed consent for publication of the patient’s clinical details was obtained and a copy of the consent form is available for review by the Editor.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Footnotes

Enhanced digital features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.7145852.

References

- 1.Weil BR, Young RF, Shen X, et al. Brief myocardial ischemia produces cardiac troponin I release and focal myocyte apoptosis in the absence of pathological infarction in swine. J Am Coll Cardiol Basic Transl Sci. 2017;2(2):105–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2017.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams JE, III, Bodor GS, Dávila-Román VG, et al. Cardiac troponin I. A marker with high specificity for cardiac injury. Circulation. 1993;88(1):101–106. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.88.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garg P, Morris P, Fazlanie AL, et al. Cardiac biomarkers of acute coronary syndrome: from history to high-sensitivity cardiac troponin. Intern Emerg Med. 2017;12(2):147–155. doi: 10.1007/s11739-017-1612-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weber M, Bazzino O, Navarro Estrada JL, et al. Improved diagnostic and prognostic performance of a new high-sensitive troponin T assay in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Am Heart J. 2011;162(1):81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Higgins JP, Higgins JA. Elevation of cardiac troponin I indicates more than myocardial ischemia. Clin Investig Med. 2003;26(3):133–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ammann P, Fehr T, Minder EI, et al. Elevation of troponin I in sepsis and septic shock. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27(6):965–969. doi: 10.1007/s001340100920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bakshi TK, Choo MK, Edwards CC, et al. Causes of elevated troponin I with a normal coronary angiogram. Intern Med J. 2002;32(11):520–525. doi: 10.1046/j.1445-5994.2002.00270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hijazi Z, Wallentin L, Siegbahn A, et al. High-sensitivity troponin T and risk stratification in patients with atrial fibrillation during treatment with apixaban or warfarin. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(1):52–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.07.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horwich TB, Patel J, MacLellan WR, et al. Cardiac troponin I is associated with impaired hemodynamics, progressive left ventricular dysfunction, and increased mortality rates in advanced heart failure. Circulation. 2003;108(7):833–838. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000084543.79097.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hassan HC, Howlin K, Jefferys A, et al. High-sensitivity troponin as a predictor of cardiac events and mortality in the stable dialysis population. Clin Chem. 2014;60(2):389–398. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2013.207142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friden V, Starnberg K, Muslimovic A, et al. Clearance of cardiac troponin T with and without kidney function. Clin Biochem. 2017;50(9):468–474. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2017.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lum G, Solarz DE, Farney L. False positive cardiac troponin results in patients without acute myocardial infarction. Lab Med. 2006;37(9):546–550. doi: 10.1309/T94UUXTJ3TX5Y9W2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okyay K, Yıldırır A. The preanalytical and analytical factors responsible for false-positive cardiac troponins. Anatol J Cardiol. 2015;15(3):264–265. doi: 10.5152/akd.2015.6006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nordestgaard BG, Chapman MJ, Humphries SE, et al. Familial hypercholesterolaemia is underdiagnosed and undertreated in the general population: guidance for clinicians to prevent coronary heart disease: consensus statement of the European Atherosclerosis Society. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(45):3478–3490a. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaplan IV, Levinson SS. When is a heterophile antibody not a heterophile antibody? When it is an antibody against a specific immunogen. Clin Chem. 1999;45(5):616–618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kricka LJ, Schmerfeld-Pruss D, Senior M, et al. Interference by human anti-mouse antibody in two-site immunoassays. Clin Chem. 1990;36(6):892–894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fortescue EB, Shin AY, Greenes DS, et al. Cardiac troponin increases among runners in the Boston Marathon. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49(2):137–143e1. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tulloh L, Robinson D, Patel A, et al. Raised troponin T and echocardiographic abnormalities after prolonged strenuous exercise—the Australian Ironman Triathlon. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40(7):605–609. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2005.022319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siegel AJ, Stec JJ, Lipinska I, et al. Effect of marathon running on inflammatory and hemostatic markers. Am J Cardiol. 2001;88(8):918–920a9. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(01)01909-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lippi G, Schena F, Salvagno GL, et al. Influence of a half-marathon run on NT-proBNP and troponin T. Clin Lab. 2008;54(7–8):251–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shave R, George KP, Atkinson G, et al. Exercise-induced cardiac troponin T release: a meta-analysis. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(12):2099–2106. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e318153ff78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Middleton N, George K, Whyte G, et al. Cardiac troponin T release is stimulated by endurance exercise in healthy humans. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(22):1813–1814. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.03.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siegel AJ, Lewandrowski KB, Strauss HW, et al. Normal post-race antimyosin myocardial scintigraphy in asymptomatic marathon runners with elevated serum creatine kinase MB isoenzyme and troponin T levels. Evidence against silent myocardial cell necrosis. Cardiology. 1995;86(6):451–456. doi: 10.1159/000176922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roos A, Bandstein N, Lundback M, et al. Stable high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T levels and outcomes in patients with chest pain. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(18):2226–2236. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.08.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.