Abstract

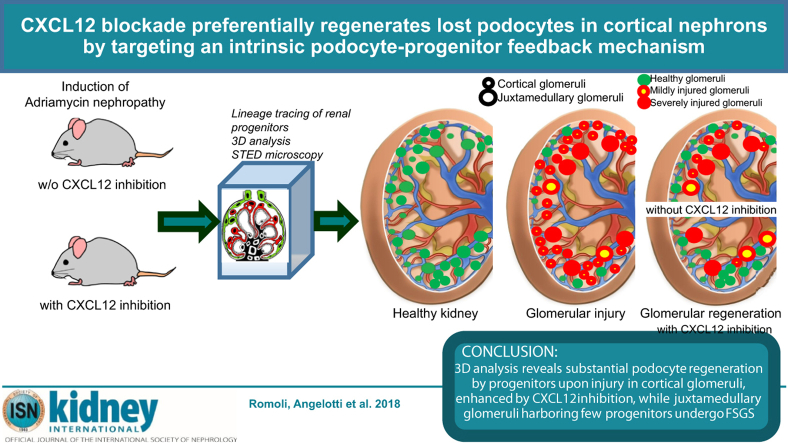

Insufficient podocyte regeneration after injury is a central pathomechanism of glomerulosclerosis and chronic kidney disease. Podocytes constitutively secrete the chemokine CXCL12, which is known to regulate homing and activation of stem cells; hence we hypothesized a similar effect of CXCL12 on podocyte progenitors. CXCL12 blockade increased podocyte numbers and attenuated proteinuria in mice with Adriamycin-induced nephropathy. Similar studies in lineage-tracing mice revealed enhanced de novo podocyte formation from parietal epithelial cells in the setting of CXCL12 blockade. Super-resolution microscopy documented full integration of these progenitor-derived podocytes into the glomerular filtration barrier, interdigitating with tertiary foot processes of neighboring podocytes. Quantitative 3D analysis revealed that conventional 2D analysis underestimated the numbers of progenitor-derived podocytes. The 3D analysis also demonstrated differences between juxtamedullary and cortical nephrons in both progenitor endowment and Adriamycin-induced podocyte loss, with more robust podocyte regeneration in cortical nephrons with CXCL12 blockade. Finally, we found that delayed CXCL12 inhibition still had protective effects. In vitro studies found that CXCL12 inhibition uncoupled Notch signaling in podocyte progenitors. These data suggest that CXCL12-driven podocyte-progenitor feedback maintains progenitor quiescence during homeostasis, but also limits their intrinsic capacity to regenerate lost podocytes, especially in cortical nephrons. CXCL12 inhibition could be an innovative therapeutic strategy in glomerular disorders.

Keywords: FSGS, glomerulosclerosis, progenitor cells, proteinuria, regeneration, STED

Graphical abstract

see commentary on page 1042

Chronic kidney disease is often a consequence of podocyte loss–related glomerulosclerosis, for example, in aging, diabetes, hypertension, and glomerulonephritis.1, 2, 3 In search of a potential cure for progressive glomerulosclerosis, we previously found that blocking the chemokine CXCL12 (CXC chemokine ligand 12; formerly named stromal cell–derived factor-1) protected mice with type 2 diabetes from albuminuria, podocyte loss, progressive glomerulosclerosis, and chronic kidney disease.4, 5 The pathophysiology behind this renoprotective effect remained unclear.

CXCL12 is an extensively studied chemokine with numerous biological functions.6 Reticular stromal cells of the bone marrow secrete CXCL12 as a signal for homing and quiescence of CXC chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4)–positive hematopoietic stem cells in their bone marrow niche.7, 8 This function is already exploited for medical use, as a single dose of a CXCR4 antagonist is sufficient to mobilize hematopoietic stem cells from their bone marrow niche into the blood stream, increasing the efficacy of stem cell apheresis for bone marrow transplantation.9 The capacity of CXCL12 to regulate the behavior of stem cells or immature progenitors has become evident in many organs including the kidney.10, 11, 12

On the basis of the aforementioned biological roles, we speculated on similar regulatory roles of CXCL12 in local progenitor cells during glomerular injury and repair. Indeed, several groups independently reported lineage tracing evidence that local podocyte progenitors can migrate to the glomerular tuft and stain positive with podocyte markers.13, 14, 15, 16 However, these data were largely debated for 4 reasons: undefined cell lineage,14, 17 low numbers of progenitors entering the tuft,13, 14, 15 conflicting evidence that these cells ultimately integrate into the glomerular filtration barrier,13, 14, 15 and absence of new podocytes in injury-unrelated kidney hypertrophy models.14, 16, 17 To overcome these limitations, we used a validated lineage tracing system for podocyte progenitors, 3-dimensional (3D) versus 2-dimensional (2D) tissue analysis, a comparison of juxtamedullary and cortical nephrons, and stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy to unravel the biology underlying the renoprotective effect of CXCL12 inhibition in glomerular disease. We hypothesized that podocyte-derived CXCL12 would be an intrinsic inhibitor of progenitor activation during homeostasis and disease and identified the same as a previously unknown podocyte-progenitor feedback mechanism. In addition, we found a series of explanations for the seemingly low numbers of regenerated podocytes in previous studies.

Results

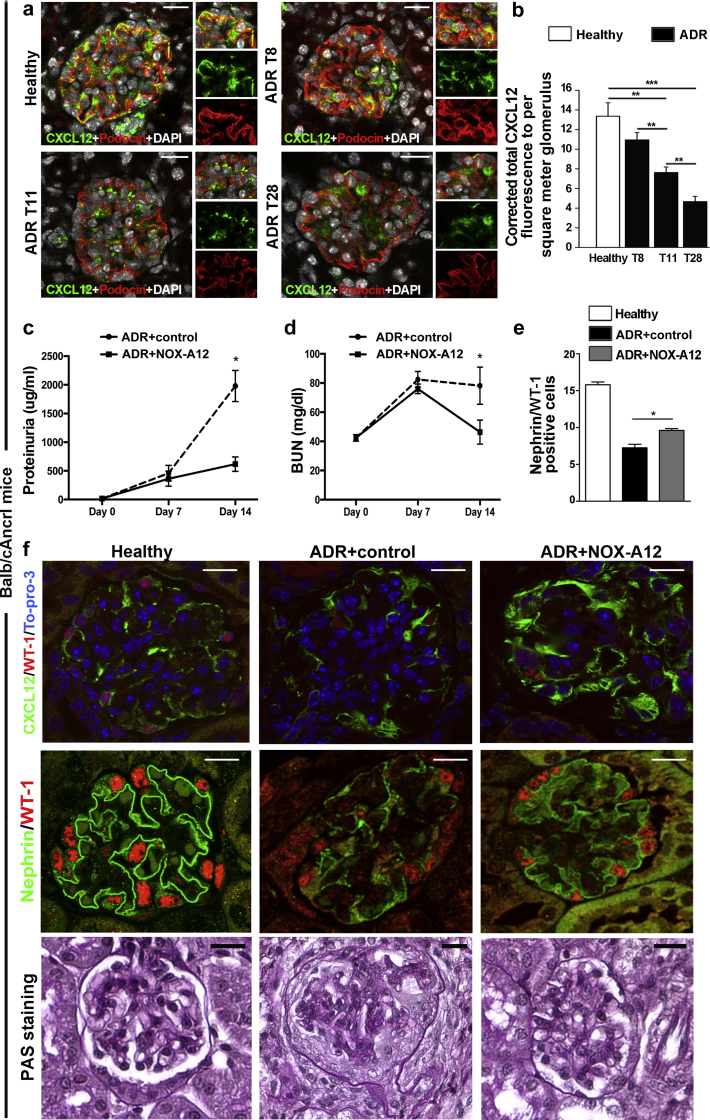

CXCL12 inhibition attenuates glomerulosclerosis in Adriamycin-induced nephropathy

We first sought to test CXCL12 blockade in a model of podocyte injury. We induced Adriamycin (ADR) nephropathy (AN) in male mice of the highly susceptible Balb/cAncrl strain that develops significant proteinuria and glomerulosclerosis within 2 weeks after a single ADR injection.18, 19 Spatial CXCL12 expression localized to the cell bodies of glomerular podocytes as demonstrated by colocalization with podocin (Figure 1a; Supplementary Figure S1A), and podocyte CXCL12 expression significantly declined with progression of AN (Figure 1a and b), revealing some positivity in von Willebrand factor–positive endothelial cells but not in claudin-1–positive parietal epithelial cells (PECs) (data not shown). In contrast, CXCL12 receptors CXCR4 and CXC chemokine receptor 7 (CXCR7) were largely expressed in glomerular cells (Supplementary Figure S1A and B). Next, we used CXCL12 inhibition with NOX-A12, a specific inhibitor that binds to CXCL12 with subnanomolar affinity, inhibits mouse CXCL12 with a half-maximal inhibitory concentration of 300 pmol/l,4 and does not affect the kidney if given to healthy mice (Supplementary Figure S1C and D). At 14 days, CXCL12 blockade had significantly increased podocyte counts and attenuated the increase in proteinuria, glomerular lesions, as well as renal dysfunction as compared with controls treated with an inactive version of the inhibitor (Figure 1c–f; Supplementary Figure S1E). Thus, CXCL12 contributes to glomerular pathology and dysfunction in AN.

Figure 1.

CXC chemokine ligand 12 (CXCL12) expression and inhibition in Adriamycin (ADR)-induced nephropathy of Balb/cAncrl mice. (a) ADR nephropathy was induced in Balb/cAncrl mice, and glomerular CXCL12 expression was assessed by immunostaining and confocal microscopy. CXCL12 is shown in green, costaining for podocin/NPHS2 in red, and cell nuclei with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) in white. Healthy control mice are shown for comparison. Insets show a detail as merged and split images for green and red colors. Bar = 20 μm. (b) Glomerular CXCL12 positivity was quantified by digital morphometry at several time points: day 8, 11, and 28 after ADR nephropathy induction (T8, T11, and T28). Data are from at least 15 glomeruli of 5 mice per group. (c–f) CXCL12 was blocked for 14 days by NOX-A12. (c) Proteinuria was determined as the urinary albumin/creatinine ratio. (d) Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) was determined as a marker of renal excretory function. (e,f) Podocytes were identified as Nephrin/WT-1+ cells by immunostaining and counted per glomerular cross section. CXCL12 expression was localized to podocytes by CXCL12 (green)/WT-1 (red)/TO-PRO-3 (blue) staining. Glomerular lesions were identified in periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)–stained sections. Bar = 20 μm. Data are mean ± SEM from at least 5 mice per group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. To optimize viewing of this image, please see the online version of this article at www.kidney-international.org.

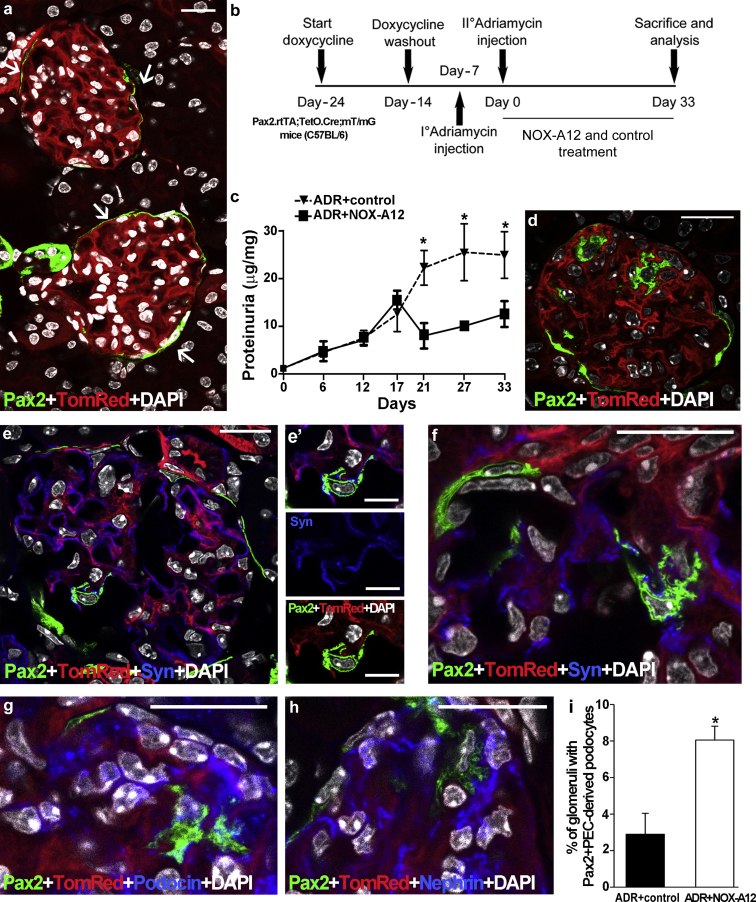

CXCL12 inhibition promotes de novo podocyte formation from Pax2+ PECs in AN

Testing for a specific role of CXCL12 in progenitor-driven podocyte regeneration in vivo requires a lineage tracing approach with specific and irreversible labeling of progenitors before the onset of injury. For this we used Pax2.rtTA;TetO.Cre;mT/mG, a transgenic mouse strain allowing lineage tracing of podocyte progenitors as well as quantifying the effects of drugs to modulate their capacity to replace podocytes lost during glomerular injury, for example, in AN.13, 20 Hence, we first induced the mT/mG transgene switch in Pax2+ cells with doxycycline, which resulted in selective green fluorescent protein (GFP) labeling of the Pax2+ subset of PECs in glomeruli (Figure 2a). Neither podocytes nor any other cell type of the glomerular tuft were labeled with GFP before injury (Figure 2a). After a doxycycline washout of 1 week, fate mapping of these cells became possible (Figure 2b). Potential Cre leakage and subsequent GFP positivity of cells in the absence of doxycycline was excluded by appropriate long-term control experiments as previously reported in detail (Supplementary Figure S2).13 Only then we induced AN by 2 subsequent injections, because the less susceptible genetic background of transgenic mice required a different protocol for AN induction (Figure 2b). CXCL12 inhibition significantly reduced proteinuria, whereas the inactive compound displayed a progressive increase in proteinuria with time (Figure 2c). These readouts were associated with the appearance of Pax2+PEC-derived green cells within the glomerular tuft (Figure 2d) that costained with the podocyte markers synaptopodin, podocin, and nephrin (Figure 2e–h), as well as with podocyte morphology (Figure 2g). Quantitative 2D analysis revealed a significant increase in glomeruli with Pax2+PEC-derived new podocytes in mice treated with the CXCL12 inhibitor (Figure 2i) (ADR+control: 1.07 ± 0.06; ADR+NOX-A12: 1.66 ± 0.25 Pax2+PEC-derived new podocytes per glomerulus) (data not shown). We conclude that CXCL12 inhibition promotes de novo podocyte formation from Pax2+PECs in AN.

Figure 2.

CXC chemokine ligand 12 inhibition drives de novo podocyte generation from Pax2+ progenitor cells in mice of the C57BL/6 background. (a) Representative glomeruli with Pax2+ cells (green) in Bowman’s capsule (arrows) in the cortex of a healthy Pax2.rtTA;TetO.Cre;mT/mG mouse kidney (Pax2+TomRed). (b) Experimental scheme of control- and NOX-A12–treated Pax2+TomRed mice with Adriamycin (ADR)-induced nephropathy. I° and II°, first and second injections, respectively, of doxorubicin hydrochloride. (c) Albumin/creatinine ratio in control- and NOX-A12–treated Pax2+TomRed mice with ADR-induced nephropathy; day 0 corresponds to the time of second doxorubicin injection. *P < 0.05. (d) Representative glomerulus of a NOX-A12–treated Pax2+TomRed mouse with ADR-induced nephropathy. Pax2+PEC–derived cells (green) are now also observed inside the glomerular tuft. (e–h) Such intraglomerular Pax2+PEC–derived cells colabel with the podocyte markers synaptopodin (Syn; e and f: blue), podocin (g: blue), and nephrin (h: blue) and present a podocyte-like appearance with primary and secondary foot processes. Split images of Pax2+PEC–derived Syn+ cell inside the glomerulus is shown. 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) counterstains nuclei (white). (i) Percentage of glomeruli with Pax2+PEC–derived podocytes over total number of glomeruli in control- and NOX-A12–treated Pax2+TomRed mice with ADR-induced nephropathy. n = 4 for each group. *P < 0.05. PEC, parietal epithelial cell. (a,d,e,f,g,h) Bar = 20 μm. (e′) Bar = 10 μm. To optimize viewing of this image, please see the online version of this article at www.kidney-international.org.

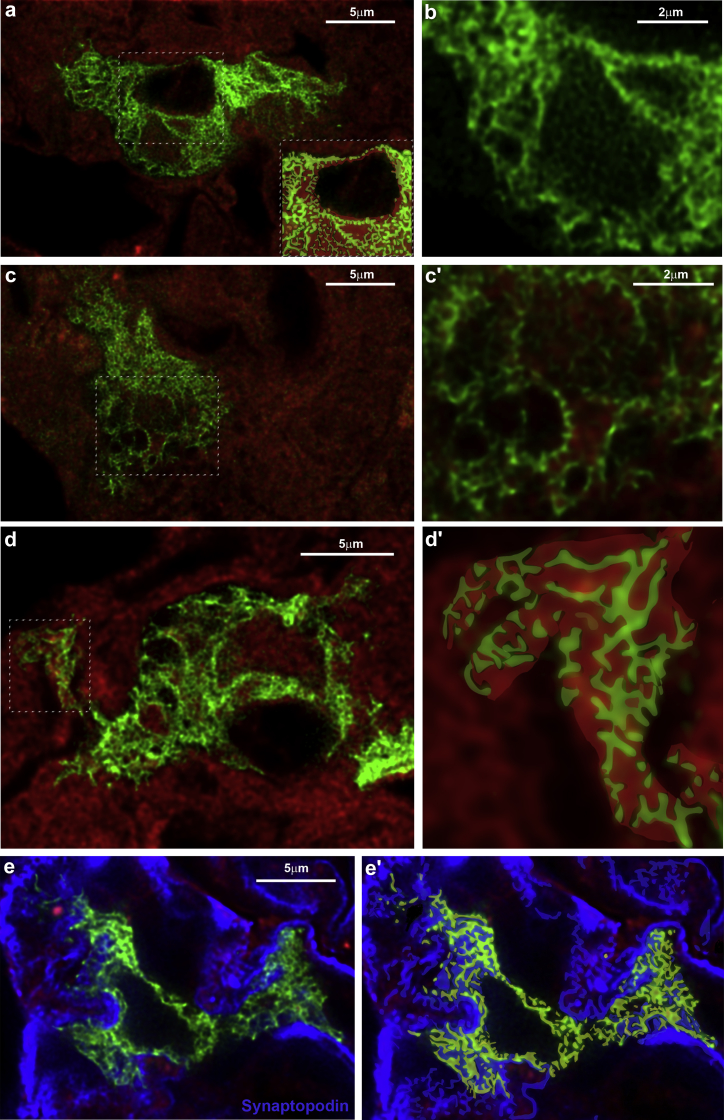

STED super-resolution microscopy reveals new podocytes to fully integrate into the glomerular filtration barrier

To evaluate the ultrastructural phenotypic features of Pax2+PEC-derived cells within the tuft, we performed STED super-resolution microscopy. The mutually exclusive expression of GFP or tdTomato in new versus preexisting podocytes allowed us to image areas where alternating foot processes are expressing GFP or tdTomato, respectively (Figure 3; Movie S1). Morphometric analyses revealed that the width of individual tertiary foot processes of regenerated podocytes was comparable to that determined by transmission electron microscopy, with dimensions ranging from 0.1 to 0.2 μm (Figure 3). Interdigitating tertiary foot processes between new and preexisting podocytes also presented at the expected distance of 0.04 μm (Figure 3). Indeed, secondary and tertiary foot processes interdigitating between regenerated and preexisting podocytes both expressing synaptopodin (Figure 3e) surrounded the entire glomerular capillaries by forming a whole net revealing slit diaphragms (Figure 3). Thus, the Pax2+PEC-derived cells display all structural features of fully differentiated podocytes and fully integrate into the injured glomerular filtration barrier.

Figure 3.

Stimulated emission depletion (STED) analysis reveals that Pax2-derived podocytes are fully differentiated and integrated into the glomerular filtration barrier. (a) Representative STED image of a Pax2-derived podocyte (enhanced green fluorescent protein [EGFP+], green) inside the glomerular tuft of an Adriamycin (ADR) Pax2.rtTA;TetO.Cre;mT/mG mouse treated with NOX-A12. Gated STED microscopy was applied to EGFP. The image was deconvolved using Huygens Professional software. The inset shows a drawing of the boxed area to better visualize tertiary foot processes interdigitating with those of preexisting podocytes. Bar = 5 μm. (b) Higher magnification of the ultrastructure of the Pax2-derived podocyte in (a). Bar = 2 μm. (c) Representative deconvolved STED image of a Pax2-derived podocyte. Bar = 5 μm. (c′) Higher magnification of the boxed area in (c). Bar = 2 μm. (d) Representative deconvolved STED image of a Pax2-derived podocyte. Bar = 5 μm. (d′) Drawing of the boxed area in (d) to better visualize the foot processes wrapping the capillaries. (e) Representative deconvolved STED image of a Pax2-derived podocyte stained with anti-Synaptopodin antibody (blue). Gated pulsed STED was applied to EGFP and Alexa Fluor 647 fluorophore. Bar = 5 μm. (e′) Drawing of (e) showing the foot processes (green) interdigitating with those of preexisting podocytes (blue). To optimize viewing of this image, please see the online version of this article at www.kidney-international.org.

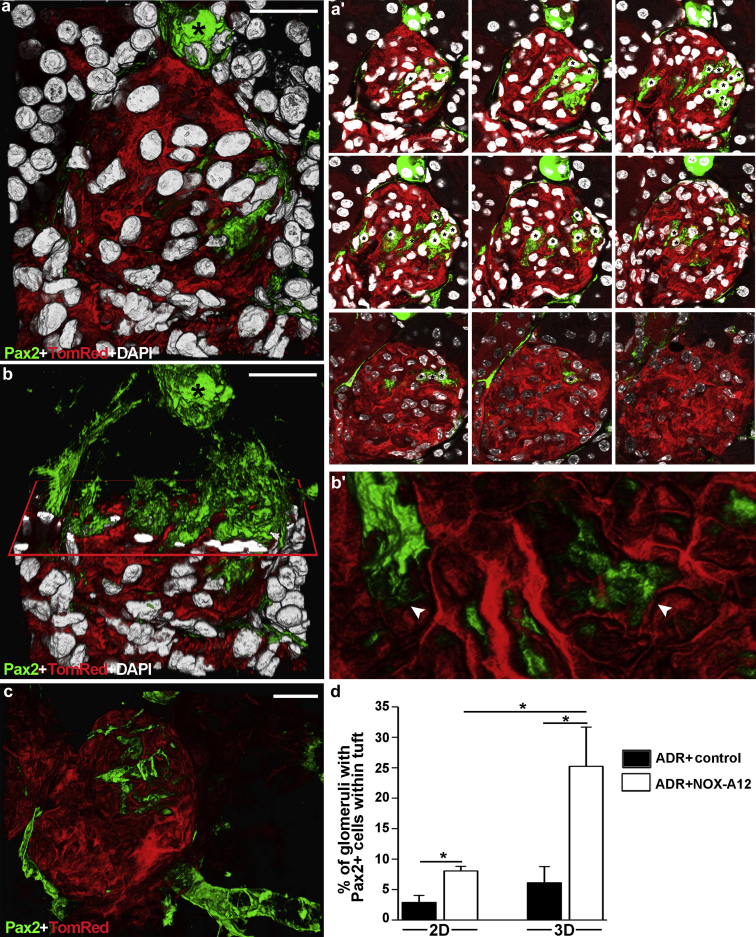

Quantitative 3D analysis shows more podocyte regeneration than what can be revealed by conventional 2D tissue analysis

The percentage of glomeruli displaying novel Pax2+PEC-derived podocytes appeared a bit less to explain the profound effects of CXCL12 inhibition on proteinuria and glomerulosclerosis. Upon speculating on a low sensitivity of conventional 2D tissue analysis, we also performed 3D analysis on the same kidneys that revealed approximately 3-fold higher numbers of glomeruli with de novo Pax2+PEC-derived podocytes and that CXCL12 blockade induced podocyte regeneration in as many as 25% of all glomeruli in this model of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (Figure 4). The z-stack analysis used to perform the 3D reconstruction of the glomerulus showed that the detection of regenerated podocytes was highly dependent on which section was used for 2D analysis and its thickness (Figure 4a′; Movie S2). Indeed, the possibility to detect regenerated podocytes with 10-μm sections used for histology was quite low. In particular, 2D analysis had a low probability of detecting the regenerated podocytes localized inside the tuft and their intricate foot processes interaction, which could instead be appreciated with 3D analysis (Figure 4b, b′, and c). Thus, quantitative 3D analysis overts substantially more podocyte regeneration than what can be revealed by conventional 2D analysis.

Figure 4.

Quantitative 3-dimensional (3D) analysis overts substantially more podocyte regeneration than what can be detected by conventional 2-dimensional (2D) analysis. (a) 3D reconstruction of a glomerulus showing Pax2+PEC–derived podocytes inside the glomerular tuft in NOX-A12–treated Pax2.rtTA;TetO.Cre;mT/mG mouse (Pax2+TomRed). (a′) Representative 2D z-section stacks of the 3D reconstruction shown in (a). Images were taken from a 50-μm-thick kidney slice, acquired at 1-μm interval. Asterisks indicate the different number of Pax2+PEC-derived podocytes counted inside the glomerular tuft in each 2D image. (b) 3D reconstruction of the same glomerulus shown in (a) with an x-plane (red) added to virtually dissect the glomerulus in 2 parts. In the upper part, only green signal is shown; in the lower part, all 3 colors are shown. (b′) Higher magnification of foot processes from Pax2+PEC–derived podocytes in (b) (arrowheads). (c) 3D reconstruction of a glomerulus showing Pax2+ cells in the epithelium of Bowman’s capsule and Pax2+PEC–derived podocytes inside the tuft. 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) counterstains nuclei (white). (d) Percentage of glomeruli with Pax2+ cells within the tuft over total number of glomeruli. Quantitative analysis was performed in 10-μm-thick slices (2D analysis) and in 50-μm-thick slices (3D analysis) in control- and NOX-A12–treated Pax2+TomRed mice with Adriamycin (ADR)-induced nephropathy. *P < 0.05. (a,a′,b,c) Bar = 20 μm. (b′) Bar = 10 μm. To optimize viewing of this image, please see the online version of this article at www.kidney-international.org.

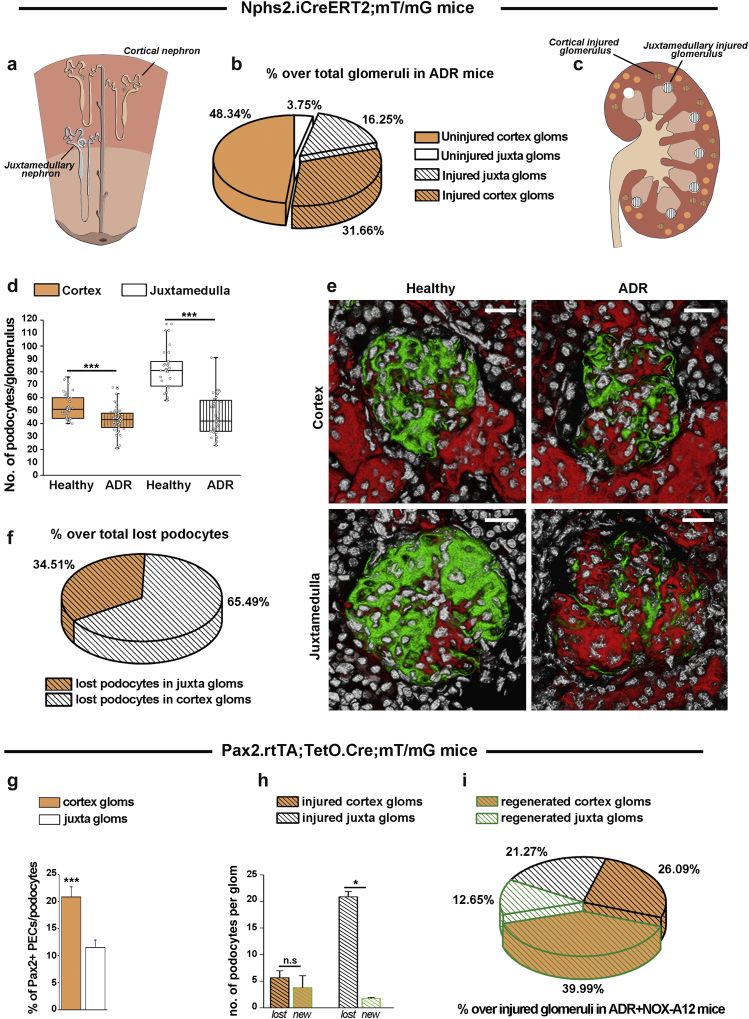

Juxtamedullary and cortical nephrons differ in terms of podocyte loss and podocyte regeneration

As a second possible reason, we speculated that in AN not all nephrons would be injured and indeed require podocyte regeneration. To address this issue, we used Nphs2.iCreERT2;mT/mG mice that, upon transgene induction, allow us to specifically irreversibly label preexisting podocytes in green and to define podocyte endowment and quantitative loss during AN by 3D analysis. We found that only 47.91% of nephrons were injured. Interstingly, 3D analysis revealed large differences in podocyte numbers and injury in cortical and juxtamedullary nephrons (Figure 5a–f). Higher percentages of juxtamedullary nephrons than of cortical nephrons faced injury (81.25% of juxtamedullary nephrons vs. 39.58% of cortical nephrons), but as juxtamedullary nephrons constituted only 20% of all nephrons, the absolute number of injured cortical nephrons was twice as high (Figure 5a–c). In addition, juxtamedullary nephrons were endowed with significantly more podocytes at baseline of which they lost ∼35% whereas cortical nephrons had less podocytes and lost only ∼15% during AN (Figure 5d). Thus, the few juxtamedullary nephrons injured lost 4 times more podocytes per nephron than did cortical nephrons (Figure 5h) and altogether lost almost twice as many podocytes than did cortical nephrons (Figures 5f). Next, we used Pax2.rtTA;TetO.Cre;mT/mG mice that allow us to irreversibly label Pax2+ progenitors and define progenitor endowment before as well as de novo podocyte generation during AN in the 2 types of nephrons by 3D analysis. Cortical nephrons were endowed with twice as many Pax2+ progenitors per glomerular podocyte count at baseline (Figure 5g). Pax2+ progenitors regenerated virtually all podocytes lost in cortical nephrons but <10% of podocytes lost in juxtamedullary nephrons (Figure 5h). Thus, the 25% of glomeruli involving Pax2+ cells for podocyte regeneration over total number of glomeruli actually represented the 52.64% of all injured glomeruli and were in large part completely regenerated, limiting the residual podocyte loss to a small subset of highly injured juxtamedullary glomeruli (Figure 5i). In summary, our 3D analysis revealed that juxtamedullary and cortical nephrons differ in terms of progenitor and podocyte endowment, podocyte loss during AN, and their capacity to replace lost podocytes and to repair filtration barrier injury.

Figure 5.

Adriamycin (ADR)-induced glomerular injury and regeneration in cortical versus juxtamedullary glomeruli.Nphs2.iCreERT2;mT/mG mice were induced with tamoxifen, which labeled all cells expressing Nphs2, that is, the podocytes, at the moment of induction in green. All other cells remain red, including all cells upregulating Nphs2 at any later time point. After a washout period, ADR nephropathy was induced in some mice (ADR group). At 4 weeks after injury, animals were killed. (a) Schematic representation of the different localization of cortical (orange) and juxtamedullary (white) nephrons. (b) Percentage of uninjured and injured glomeruli (black dashes) in the cortex and juxtamedulla over the total number of glomeruli in ADR mice. Injured glomeruli in each region were defined as glomeruli with a podocyte number lower than the mean-3SD value in healthy mice (41 for cortical glomeruli and 61.2 for juxtamedullary glomeruli). Data are mean from 20 glomeruli per mouse. (c) Schematic representation of the different position, dimension, and injury in cortical versus juxtamedullary glomeruli in mice at 4 weeks after ADR. (d) Number of podocytes per glomerulus in the cortex (orange boxes) and juxtamedulla (white boxes). The analysis was performed on healthy controls to compare the number of podocytes in each type of glomerulus and in ADR mice (dashed boxes) to determine the number of lost podocytes in each type of glomerulus. Data are mean ± SEM from at least 15 glomeruli per mouse. n = 4 healthy mice, and n = 4 ADR mice. ***P < 0.001 versus healthy mice. (e) Representative 3-dimensional images for each group. Bar = 20 μm. (f) Percentage of podocytes lost in cortical and juxtamedullary glomeruli over the total number of lost podocytes in ADR mice. Data are mean from at least 15 glomeruli per mouse. n = 4 mice. (g) Percentage of Pax2+PECs in Bowman’s capsule over podocytes in cortical (orange) and juxtamedullary (white) glomeruli of Pax2.rtTA;TetO.Cre;mT/mG mice. Data are mean ± SEM from at least 15 glomeruli per mouse. n = 3 mice. (h) Number of lost (black dashed columns) and new (green dashed columns) podocytes per glomerulus in the cortex (orange columns) and juxtamedulla (white columns) in ADR+NOX-A12 mice (n = 4). Lost podocytes were calculated, as in (d), in ADR Nphs2.iCreERT2;mT/mG mice, and new podocytes were defined as Pax2-derived podocytes inside the tuft in ADR+NOX-A12 Pax2.rtTA;TetO.Cre;mT/mG mice. Data are mean ± SEM. n = 4 mice per group. (i) Percentage of regenerated glomeruli (green dashes) over total number of injured glomeruli in ADR mice treated with NOX-A12. Regenerated glomeruli were defined as glomeruli with Pax2-derived podocytes (green) inside the tuft in Pax2.rtTA;TetO.Cre;mT/mG mice. All quantitative analyses were performed in 50-μm-thick slices (3D analysis). Cortex glom, cortical glomerulus; Juxta glom, juxtamedullary glomerulus; PEC, parietal epithelial cell. To optimize viewing of this image, please see the online version of this article at www.kidney-international.org.

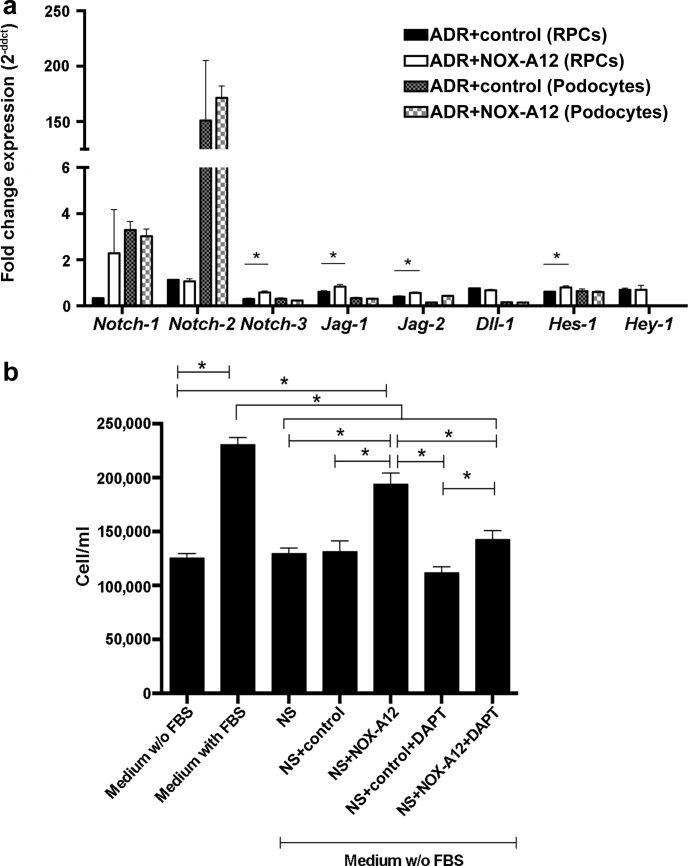

CXCL12 suppresses the activation of podocyte progenitors by suppressing Notch signaling

We have previously shown that CXCL12 suppresses renal progenitor cells (RPCs) to differentiate into podocytes in vitro.5 As Notch is an important regulator of the progenitor-podocyte axis,21 we explored the possibility that intrinsic CXCL12 is a regulator of Notch signaling in these cells by performing further in vitro studies. CXCL12 inhibition upregulated Notch-related genes in ADR-stimulated RPCs but not in differentiated podocytes (Figure 6a). In addition, podocyte supernatants alone did not elicit mitogenic effects on RPCs but adding CXCL12 inhibitor did—an effect that was completely neutralized by the Notch inhibitor N-[N-(3,5-difluorophenacetyl)-1-alanyl]-S-phenylglycine t-butyl ester (Figure 6b). Thus, intrinsic CXCL12 suppresses Notch whereas CXCL12 inhibition recovers Notch signaling in Pax2+PECs and promotes their activation. We previously reported that RPCs selectively express Notch-3 proteins during AN.21 On the basis of this observation, we performed immunostaining for the Notch-3 intracellular domain. Our results confimed that Notch-3 localized mostly to RPCs of injured glomeruli. Interestingly, Notch-3 protein expression in RPCs was also markedly increased with CXCL12 inhibition in Balb/cAncrl mice (Supplementary Figure S3). Together, these results show that CXCL12 inhibition induces Notch expression in RPCs during glomerular injury, promoting their activation.

Figure 6.

CXC chemokine ligand 12 (CXCL12) modulates Notch signaling in renal progenitor cells in vitro and in adriamycin (ADR)-induced nephropathy in vivo. (a) CXCL12 inhibition induced Notch-related transcripts in renal progenitor cells (RPCs), but not in podocytes in vitro. All samples were treated with CXCL12 (100 nM), doxorubicin (2.5 μM), and revNOX-A12 (1 mg/ml; control) or NOX-A12 (1 mg/ml). Data are expressed as fold change expression compared to the cells treated with CXCL12 and doxorubicin in 3 independent experiments, each performed in quintuplicate. *P < 0.05. (b) RPCs were cultured in normal medium with or without fetal bovine serum (FBS) and addition of necrotic podocyte supernatant (NS), CXCL12 inhibitor (NOX-A12), control (revNOX-A12), and the γ-secretase and Notch inhibitor DAPT (N-[N-(3,5-difluorophenacetyl)-1-alanyl]-S-phenylglycine t-butyl ester). Cells were counted to quantify RPC proliferation. Data are mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments, each performed in quintuplicate. Statistical testing was done as indicated. *P < 0.05.

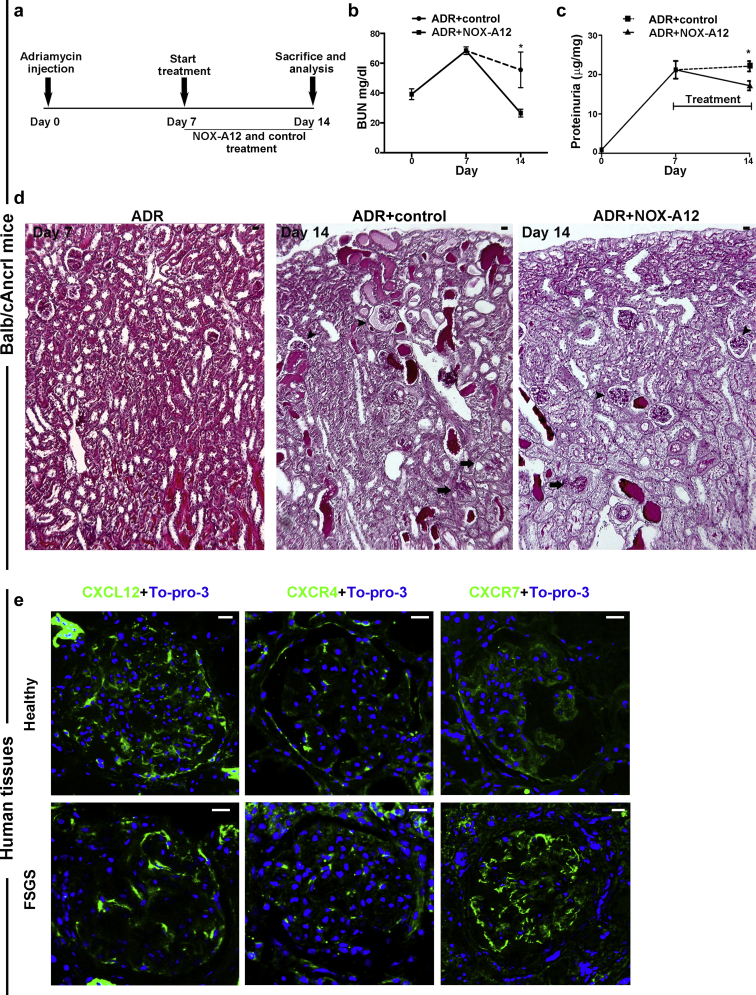

Delayed onset of CXCL12 inhibition is still therapeutic

Based on the above discussion, selective CXCL12 inhibition should improve outcomes of glomerular injury, mainly by modulating the healing phase of glomerular injury. This characteristic could potentially offer the opportunity for delayed intervention, which is important from a clinical perspective, as diagnosis is mostly made late in the disease process. To test this concept, we repeated identical AN experiments in Balb/cAncrl mice as before but initiated CXCL12 inhibition only from day 7, a time point where proteinuria was already present but structural injury was not yet as obvious as compared to later time points (Figure 7a–d). Also, delayed onset of CXCL12 inhibition significantly improved blood urea nitrogen levels, proteinuria, and reduced cortical glomerular lesions (Figure 7b–d). Together, even delayed onset of CXCL12 blockade has the capacity to improve outcomes of glomerular injury.

Figure 7.

Delayed onset of CXC chemokine ligand 12 (CXCL12) inhibition improves functional and structural outcomes in adriamycin (ADR)-induced nephropathy of Balb/cAncrl mice—CXCL12, CXC chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4), and CXC chemokine receptor 7 (CXCR7) expression in human kidney. (a) ADR nephropathy was induced in Balb/cAncrl mice and CXCL12 was blocked by NOX-A12 from day 7 to day 14. (b) Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) was determined as a marker of renal excretory function. (c) Proteinuria was determined as the urinary albumin/creatinine ratio. Data are mean ± SEM from at least 5 mice per group. (d) Periodic acid-Schiff–stained sections of ADR mice at day 7 before treatments and of ADR mice treated with control or NOXA-A12 from day 7 to day 14. Control mice with ADR-induced nephropathy revealed severe lesions in juxtamedullary glomeruli (arrows) and also in some cortical glomeruli (arrowheads). CXCL12 inhibition with NOX-A12 reduced lesions, especially in cortical glomeruli (arrowheads) but less in juxtamedullary glomeruli (arrows). (e) Healthy human kidney tissues and diagnostic biopsies of patients with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) were stained for CXCL12, CXCR4, or CXCR7 (green) and nuclear DNA (TO-PRO-3, blue). Images of representative glomeruli were obtained by confocal microscopy. Bar = 20 μm. ∗P < 0.05 versus ADR inhibitor control group. To optimize viewing of this image, please see the online version of this article at www.kidney-international.org.

CXCL12 in human focal segmental glomerulosclerosis

To examine the expression of CXCL12 and its receptors in human kidneys, we stained tissue samples of healthy kidneys obtained from tumor-free nephrectomy samples and diagnostic biopsies from patients found to be affected by focal segmental glomerulosclerosis with antibodies specific for CXCL12, CXCR4, and CXCR7. In healthy kidneys, CXCL12 was expressed by all glomerular epithelial cells, cells of the glomerular tuft, and PECs along Bowman’s capsule (Figure 7e). CXCR4 was mostly expressed in PECs, and CXCR7 was found in all cells of the tuft as well as in PECs. In focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, CXCL12 showed the same distribution pattern to parietal and visceral epithelia as far these were maintained outside lesions. CXCR4 staining intensity of the capsule had declined, whereas staining intensity of CXCR7 in podocytes was strongly induced as compared to respective healthy human tissues (Figure 7e). We conclude that CXCL12 and its receptors are expressed in both types of glomerular epithelia in human kidneys, that is, podocytes and PECs.

Discussion

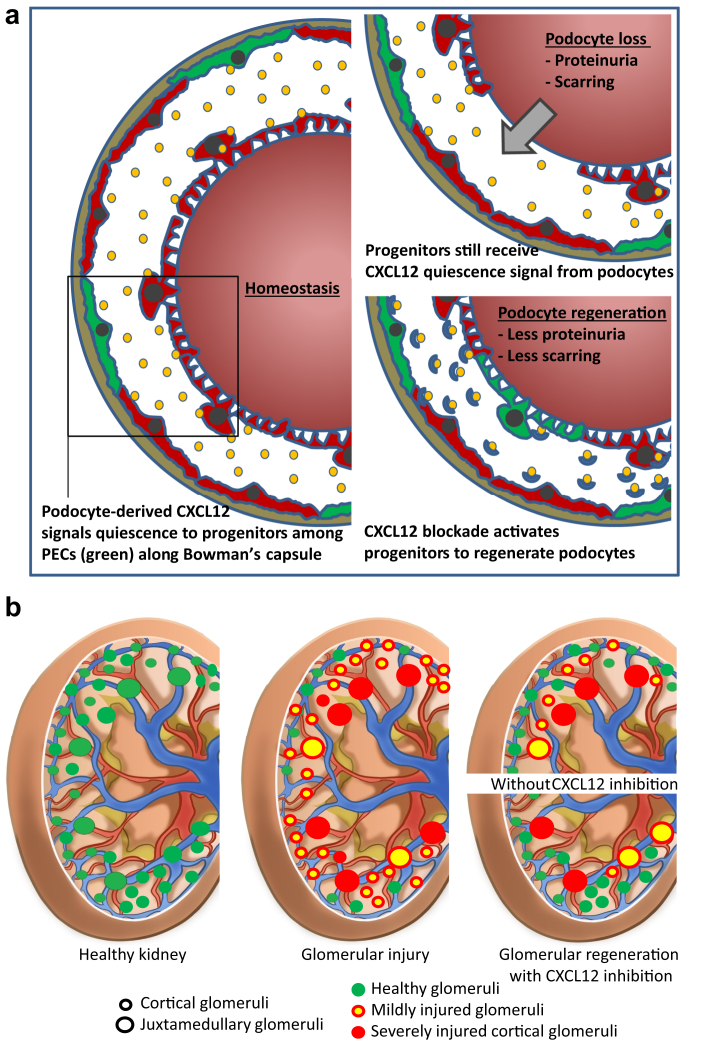

We had hypothesized that the constitutive expression of CXCL12 by podocytes has a homeostatic effect on their local progenitors conceptually similar to its role in the bone marrow and in other stem cell niches7 and that this podocyte-progenitor feedback also suppresses the intrinsic capacity of progenitors for podocyte regeneration upon injury-related podocyte loss. Our data confirm this concept and further demonstrate that CXCL12 inhibition can improve outcomes of AN by stimulating Pax2+ progenitors along Bowman’s capsule to migrate in relevant numbers to the glomerular tuft, differentiate into podocytes that fully integrate into the glomerular filtration barrier, and attenuate proteinuria and chronic kidney disease progression (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

CXC chemokine ligand 12 (CXCL12)–driven podocyte-progenitor feedback mechanism for regenerating injury in cortical glomeruli. (a) Note that focal podocyte injury does not necessarily abrogate the exposure of progenitors within the parietal epithelial cell (PEC) layer to CXCL12 secreted by other podocytes, a process that sustains the inhibition of Notch signaling and progenitor activation that would be needed for podocyte regeneration. CXCL12 blockade can overcome this intrinsic negative feedback and enforce podocyte regeneration, repair glomerular filtration barrier injury, reduce proteinuria, and prevent from glomerulosclerosis. (b) Toxic glomerular injury (red glomeruli) affects predominately glomeruli of juxtamedullary nephrons (large circles) that are also less endowed with podocyte progenitors and therefore frequently end in irreversible glomerular scarring and persistent proteinuria. In contrast, glomeruli of cortical nephrons (smaller circles), that is, 80% of all nephrons, face rather mild podocyte injury (yellow glomeruli) and are equipped with more podocyte progenitors and thus frequently completely recover from filtration barrier injury by podocyte regeneration (green glomeruli); therapeutic CXCL12 inhibition can stimulate progenitor-driven podocyte regeneration according to the predominant distribution of progenitors in cortical nephrons, which improves renal function and reduces proteinuria, with remaining proteinuria from nonregenerated juxtamedullary nephrons.

Starting from our first description of RPCs differentiating into podocytes, the concept of an intrinsic source of podocyte regeneration has been much debated. Here we provide further data to resolve this issue using a lineage tracing tool validated for fate mapping of renal progenitors during kidney development and regeneration after glomerular and tubular injury,13 3D analysis, and STED super-resolution microscopy. The last, for the first time, ultimately proves that Pax2+ progenitor-derived cells replace lost podocytes by fully integrating into the glomerular filtration barrier. In addition, we provide 2 novel explanations for the apparently low number of regenerated podocytes, a source of doubts that intrinsic podocyte regeneration could be meaningful in terms of clinical outcomes. First, quantitative 3D analysis revealed that the traditional 2D tissue analysis largely underestimates the true amount of regenerated podocytes, completely missing those glomeruli where few regenerated podocytes are present. Second, we performed a separate analysis of cortical versus juxtamedullary nephrons, stimulated by the observation that the latter are more severely injured in many disorders including AN22, 23, 24 and are more frequently and more severely affected by glomerulosclerosis.25, 26 Our data suggest that juxtamedullary nephrons, which represent only 20% of glomeruli, harbor more podocytes because they are larger,27, 28, 29 face substantially more ADR-induced podocyte loss, and recover less from injury because they are endowed with less Pax2+ progenitors per podocyte. In contrast, cortical nephrons are smaller but much more numerous,27, 28 have less podocytes, and lose only few podocytes during AN, which they can recover more easily because cortical nephrons have more Pax2+ progenitors per podocyte. Therefore, with CXCL12 blockade the vast majority of injured cortical nephrons fully recover from injury upon ADR exposure. This may explain the strong reduction of proteinuria observed with CXCL12 blockade. In contrast, juxtamedullary nephrons show limited regeneration, but because they represent only a small subset of glomeruli, they have a limited effect, which justifies mild residual proteinuria. Interestingly, previous studies showed that angiotensin II receptor blockers reduce proteinuria by promoting glomerular regeneration selectively on cortical nephrons in rats with diabetic nephropathy.30, 31 Our findings on nephron diversity in terms of injury and intrinsic regenerative capacity may resolve several of the debates in the field and ultimately identify podocyte progenitors as a cellular target for innovative treatments for the prevention of chronic kidney disease progression in glomerular disorders.

As another innovative aspect of our study, we identify CXCL12 as a critical element of a podocyte-progenitor feedback axis, which unravels the previously unknown mechanism of action of the podocyte-protective effect of the CXCL12 inhibitor NOX-A12 in type 2 diabetic db/db mice.4, 5 We had already reported that NOX-A12 reverted CXCL12-related suppression of RPC differentiaton into podocytes in vitro, but the relevance of this phenomenon in vivo remained unknown.5 By using progenitor lineage tracing with Pax2.rtTA;TetO.Cre;mT/mG mice, we show that CXCL12 inhibition significantly enhances podocyte regeneration from their local Pax2+ progenitors. These results become particularly obvious using 3D tissue analysis. Consistently, CXCL12 inhibition substantially reduced proteinuria.

Mechanistically, CXCL12 inhibition seems to reverse the suppressive effect of podocyte-derived CXCL12 on Notch signaling and on progenitor differentation into podocytes, but other mechanism may also apply. This finding would be in line with the role of CXCL12 and Notch signaling in other stem cell niches,6, 32, 33 including the role of CXCL12 on stem cell and progenitor cell survival.6, 21, 34 CXCL12 signaling creates complex interactions with numerous other signaling pathways including Notch on stem cell functions, but the level of CXCL12 and Notch signaling has not yet been identified.35 In addition, the ability of angiotensin inhibition to suppress glomerular crescent formation through the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis might relate to enhanced progenitor differentiation into podocytes.36, 37 In addition, ADR injures endothelial cells and it is likely that endothelial cell injury inside and outside the kidney modulated some of the effects we observed, including the stimulatory effect of CXCL12 blockade on Pax2+ cell migration and differention.38, 39, 40 Indeed, podocyte injury is often a secondary effect to glomerular endothelial cell damage.38 As another limitation of our study, the mechanism of action was demonstrated only in a single injury model (ADR), albeit in 3 mouse strains and confirming our previous results obtained from a genetic model of diabetic nephropathy.4, 5

CXCL12 is also secreted by podocytes in the healthy human kidney and as human PECs in situ express both CXCL12 receptors, that is, CXCR4 and CXCR7. As in mice and humans podocyte CXCL12 expression declines with progression of glomerulosclerosis, it is likely that this mechanism described in mice also works the same way in humans. Obviously, functional proof in humans is difficult. CXCR4 antagonists should disrupt the podocyte-progenitor feedback but currently CXCR4 inhibition is approved only as one time exposure to mobilize hematopoietic stem cells from the bone marrow for allogenic stem cell transplantation. NOX-A12 is currently being tested in clinical trials as adjunctive therapy for multiple myeloma. Up to now no renal adverse events have been reported.41 Interestingly, Spiegelmers tend to increase plasma concentrations of their target, probably by retaining the inactive protein from degradation for some time.5 This may explain the more intense CXCL12 staining of mice with AN treated with NOX-A12.

In summary, podocytes constitutively express CXCL12, which maintains quiescence of Pax2+ podocyte progenitor cells within the PEC layer along Bowman’s capsule, probably via suppressing Notch signaling (Figure 8). This process limits the progenitor’s potential to regenerate lost podocytes during glomerular injury (Figure 8). Finally, 3D tissue analysis is needed to correctly quantify regeneration inside the glomerulus and STED microscopy to confirm podocyte differentiation. These analytical methods set new standards for study the effect of podocyte regeneration in response to injury and in the progression of glomerular disease as well as for analyzing the effect of potential new drugs to target podocyte regeneration (Figure 8). We conclude that the CXCL12-mediated podocyte-progenitor feedback is another in a series of previously identified mechanisms how chemokines critically determine the resolution or progression of kidney diseases.42 CXCL12 inhibition could be a novel therapeutic strategy to promote podocyte regeneration upon injury and to prevent progressive glomerulosclerosis, one of the most common causes of end-stage renal disease.

Methods

Animal studies

Balb/cAncrl mice were procured from Charles River Laboratories (Sulzfeld, Germany). Pax2.rtTA;TetO.Cre;mT/mG and Nphs2.iCreERT2;mT/mG mice of the C57BL/6 background were generated and genotyped as described previously.13 Further information is given in Supplementary Procedures.

AN induction in transgenic mice and Balb/cAncrl mice

Seven- to 8-weeks-old transgenic mice received 2 successive retro-orbital injections of 18 mg/kg of doxorubicin hydrochloride (Sigma, Darmstadt, Germany) on day 7 and day 0. Balb/cAncrl mice received a single tail vein injection of 13.4 mg/kg of doxorubicin hydrochloride as described previously.13

CXCL12 blockade

The anti-CXCL12 Spiegelmer NOX-A12 (NOXXON Pharma AG, Berlin, Germany) and a control Spiegelmer of the same length but with the reverse RNA sequence of NOX-A12 were used as described previously.4, 5 NOX-A12 binds to CXCL12 with subnanomolar affinity and inhibits mouse CXCL12 with a half-maximal inhibitory concentration of 300 pmol/l.4 For further details, see Supplementary Procedures.

Assessment of kidney injury

Detailed procedures for proteinuria and blood urea nitrogen assessment are reported in Supplementary Procedures.

Kidney tissues were fixed in 4% neutral buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin as described previously.43, 44, 45 For routine histology and morphometric analysis, 4-μm sections were stained with periodic acid-Schiff reagent.

Immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy

Confocal microscopy was performed on 10-μm frozen sections by using an SP5 AOBS confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems, Mannheim, Germany) equipped with a Chameleon Ultra II 2-photon laser (Coherent, Santa Clara, CA). Detailed procedures are given in Supplementary Procedures.

Podocyte quantification and analysis of injury and regeneration

Podocyte quantification in Nphs2.iCreERT2;mT/mG mice was performed on 3D reconstructions and the percentage of glomeruli with Pax2+PEC-derived podocytes was performed in Pax2.rtTA;TetO.Cre;mT/mG mice, both on 3D and 2D sections.

For detailed calculations, see Supplementary Procedures.

Quantification of total CXCL12 fluorescence in the glomerulus

Glomerular CXCL12 positivity was quantified as corrected total fluorescence by digital morphometry at several time points using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).45 For detailed calculations, see Supplementary Procedures.

STED microscopy

STED xyz images (i.e., z-stacks acquired along 3 directions: x, y, and z axes) were acquired by using an SP8 STED 3X confocal microscope (Leica). Collected images were deconvolved using Huygens Professional software version 18.04 (Scientific Volume Imaging B.V., Hilversum, The Netherlands) and analyzed using Imaris 7.4.2 software (Bitplane, Zurich, Switzerland). Details are given in Supplementary Procedures.

Human tissues

A total of 3 healthy kidneys and 4 renal biopsies from patients found to be affected by focal segmental glomerulosclerosis were analyzed in agreement with the Ethical Committee on Human Experimentation of the Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria Careggi, Florence, Italy. Normal kidney fragments were obtained from the pole opposite to the tumor of patients who underwent nephrectomy for localized renal tumors.

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Real-time polymerase chain reaction was performed as described previously.46 Details are given in Supplementary Procedures.

Cell culture studies

Human RPCs and podocytes were obtained as described previously.12, 21, 47, 48 Details are given in Supplementary Procedures.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 5 software (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA). Significance of differences was determined using the appropriate 2-sided t test, Mann-Whitney U test, or 1-way analysis of variance with post hoc Bonferroni correction used for multiple comparisons. A P value of <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Disclosure

DE and SK are employees of NOXXON Pharma AG, Berlin, Germany. All the other authors declared no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

Analyses of stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy were conducted in the Unit of Advanced Optical Microscopy at Clinical and Research Hospital Humanitas, Rozzano (MI), Italy. We thank Tilo Schorn, Unit of Advanced Optical Microscopy at Clinical and Research Hospital Humanitas, Rozzano (MI), for STED analysis. We gratefully acknowledged the expert technical support of Dan Draganovici and Jana Mandelbaum, Renal Division, Department of Medicine IV, University Hospital, Munich, Germany. This project has received funding from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement no. 648274). SR and HJA were supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (GRK1202 and AN372/24-1). LAG was supported by the ERA-EDTA and a postdoctoral research fellowship from the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich.

Footnotes

Figure S1. (A) Immunostaining for secondary antibodies as control for the double staining of Figure 1a (CXCL-12+Podocin+DAPI). Goat anti-mouse IgG1 (the secondary antibody of CXCL-12) in green, goat anti-rabbit IgG (the secondary antibody of Podocin) in red, and DAPI in white. Scale bar = 20 μm. (B) Immunostaining for CXCR4 and CXCR7 in Adriamycin nephropathy of Balb/cAncrl mice. Representative images are shown of healthy and injured glomeruli at different time points as indicated. Arrows point to positive cells on Bowman’s capsule. Scale bar = 25 μm. (C) CXCL12 inhibition in healthy animals showed no significant variation in the albumin/creatinine urinary ratio after 2 weeks of treatment. n = 6 per group. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. (D) No major glomerular lesions were found in the endpoint day 14 after treatment with the inhibitor compared with the control (representative pictures). n = 6 for group. Scale bars = 20 μm. (E) PAS-stained sections of Balb/cAncrl mice with Adriamycin-induced nephropathy treated with control or NOX-A12. Scale bars = 100 μm.

Figure S2. Pax2 immunostaining on mouse sections. (A,B) Pax2 immunostaining (blue) was performed on sections of healthy (A) and ADR+NOX-A12 (B) Pax2.rtTA;TetO.Cre;mT/mG mice. DAPI counterstains nuclei. Arrows point to EGFP+ cells that were also positive for Pax2-antibody (green/blue cells) in the glomerulus. Arrowheads point to cells inside the tuft that are positive for Pax2-antibody but EGFP-. Asterisk points to a Pax2-derived podocyte inside the tuft that is negative for Pax2-antibody. Bars = 20 μm.

Figure S3. Immunostaining for Notch in Balb/cAncrl mice. The Notch intracellular domain (NICD)-3 is stained in green, nephrin in red, and To-pro-3 in blue in mice with adriamycin (ADR)-induced nephropathy treated with the CXCL12 inhibitor NOX-A12 or inactive control. Note that CXCL12 inhibition induces Notch also inside the glomerulus, namely in PECs. Representative images are shown. Scale bar = 20 μm.

Supplementary Procedures.

Movie S1. STED super-resolution microscopy reveals Pax2+PEC–derived cells (EGFP+, green) within the tuft (tdTomato, red) of an Adriamycin Pax2.rtTA;TetO.Cre;mT/mG mouse treated with NOX-A12. These cells displayed all structural features of fully differentiated podocytes and fully integrated into the glomerular filtration barrier.

Movie S2. Pax2+PECs of the Bowman’s capsule generate new podocytes (green) in the injured tuft (red) of an Adriamycin Pax2.rtTA;TetO.Cre;mT/mG mouse treated with NOX-A12. Red and white signals (td Tomato and DAPI, respectively) are virtually removed along the y axis in order to better show the Pax2+PEC–derived cells (green) inside the tuft.

Supplementary material is linked to the online version of the article at www.kidney-international.org.

Contributor Information

Hans-Joachim Anders, Email: hjanders@med.uni-muenchen.de.

Paola Romagnani, Email: paola.romagnani@unifi.it.

Supplementary Material

(A) Immunostaining for secondary antibodies as control for the double staining of Figure 1A (CXCL-12+Podocin+DAPI). Goat anti mouse IgG1 (the secondary antibody of CXCL-12) in green, goat anti-rabbit IgG (the secondary antibody of Podocin) in red and DAPI in white. Scale bar= 20 μm. (B) Immunostaining for CXCR4 and CXCR7 in Adriamycin nephropathy of Balb/cAncrl mice. Representative images are shown of healthy and injured glomeruli at different time points as indicated. Arrows point positive cells on Bowman’s capsule. Scale bar = 25 μm. (C) CXCL12 inhibition in healthy animals showed no significant variation in the albumin/creatinine urinary ratio after 2 weeks of treatment. n = 6 per group. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. (D) No major glomerular lesions were found in the endpoint day 14 after treatment with the inhibitor compared with the control (representative pictures). n = 6 for group. Scale bars = 20 μm. (E) PAS-stained sections of Balb/cAncrl mice with Adriamycin-induced nephropathy treated with control or NOX-A12. Scale bars = 100 μm.

Pax2 immunostaining on mouse sections. (A,B) Pax2 immunostaining (blue) was performed on sections of healthy (A) and ADR+NOX-A12 (B) Pax2.rtTA;TetO.Cre;mT/mG mice. DAPI counterstains nuclei. Arrows point EGFP+ cells that were also positive for Pax2-antibody (green/blue cells) in the glomerulus. Arrowheads point to cells inside the tuft that are positive for Pax2-antibody but EGFP-. Asterisk points a Pax2-derived podocyte inside the tuft that is negative for Pax2-antibody. Bars = 20 μm.

Immunostaining for Notch in Balb/cAncrl mice. The Notch intracellular domain (NICD)-3 is stained in green, nephrin in red, and To-pro-3 in blue in mice with adriamycin (ADR)-induced nephropathy treated with the CXCL12 inhibitor NOX-A12 or inactive control. Note that CXCL12 inhibition induces Notch also inside the glomerulus, namely in PECs. Representative images are shown. Scale bar = 20 μm.

STED super-resolution microscopy reveals Pax2+PEC–derived cells (EGFP+, green) within the tuft (tdTomato, red) of an Adriamycin Pax2.rtTA;TetO.Cre;mT/mG mouse treated with NOX-A12. These cells displayed all structural features of fully differentiated podocytes and fully integrated into the glomerular filtration barrier.

Pax2+PECs of the Bowman’s capsule generate new podocytes (green) in the injured tuft (red) of an Adriamycin Pax2.rtTA;TetO.Cre;mT/mG mouse treated with NOX-A12. Red and white signals (td Tomato and DAPI, respectively) are virtually removed along the y axis in order to better show the Pax2+PEC–derived cells (green) inside the tuft.

References

- 1.Reiser J., Sever S. Podocyte biology and pathogenesis of kidney disease. Annu Rev Med. 2013;64:357–366. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-050311-163340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kriz W., Lemley K.V. A potential role for mechanical forces in the detachment of podocytes and the progression of CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:258–269. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014030278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Romagnani P., Remuzzi G., Glassock R. Chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17088. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sayyed S.G., Hagele H., Kulkarni O.P. Podocytes produce homeostatic chemokine stromal cell-derived factor-1/CXCL12, which contributes to glomerulosclerosis, podocyte loss and albuminuria in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2009;52:2445–2454. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1493-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Darisipudi M.N., Kulkarni O.P., Sayyed S.G. Dual blockade of the homeostatic chemokine CXCL12 and the proinflammatory chemokine CCL2 has additive protective effects on diabetic kidney disease. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:116–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anders H.J., Romagnani P., Mantovani A. Pathomechanisms: homeostatic chemokines in health, tissue regeneration, and progressive diseases. Trends Mol Med. 2014;20:154–165. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sugiyama T., Kohara H., Noda M. Maintenance of the hematopoietic stem cell pool by CXCL12-CXCR4 chemokine signaling in bone marrow stromal cell niches. Immunity. 2006;25:977–988. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nie Y., Han Y.C., Zou Y.R. CXCR4 is required for the quiescence of primitive hematopoietic cells. J Exp Med. 2008;205:777–783. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Broxmeyer H.E., Orschell C.M., Clapp D.W. Rapid mobilization of murine and human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells with AMD3100, a CXCR4 antagonist. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1307–1318. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takabatake Y., Sugiyama T., Kohara H. The CXCL12 (SDF-1)/CXCR4 axis is essential for the development of renal vasculature. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:1714–1723. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008060640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haege S., Einer C., Thiele S. CXC chemokine receptor 7 (CXCR7) regulates CXCR4 protein expression and capillary tuft development in mouse kidney. PLoS One. 2012;7:e42814. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mazzinghi B., Ronconi E., Lazzeri E. Essential but differential role for CXCR4 and CXCR7 in the therapeutic homing of human renal progenitor cells. J Exp Med. 2008;205:479–490. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lasagni L., Angelotti M.L., Ronconi E. Podocyte regeneration driven by renal progenitors determines glomerular disease remission and can be pharmacologically enhanced. Stem Cell Rep. 2015;5:248–263. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Appel D., Kershaw D.B., Smeets B. Recruitment of podocytes from glomerular parietal epithelial cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:333–343. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008070795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pippin J.W., Sparks M.A., Glenn S.T. Cells of renin lineage are progenitors of podocytes and parietal epithelial cells in experimental glomerular disease. Am J Pathol. 2013;183:542–557. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wanner N., Hartleben B., Herbach N. Unraveling the role of podocyte turnover in glomerular aging and injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:707–716. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013050452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berger K., Schulte K., Boor P. The regenerative potential of parietal epithelial cells in adult mice. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:693–705. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013050481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee V.W., Harris D.C. Adriamycin nephropathy: a model of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nephrology (Carlton) 2011;16:30–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2010.01383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teixeira Vde P., Blattner S.M., Li M. Functional consequences of integrin-linked kinase activation in podocyte damage. Kidney Int. 2005;67:514–523. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.67108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burger A., Koesters R., Schafer B.W. Generation of a novel rtTA transgenic mouse to induce time-controlled, tissue-specific alterations in Pax2-expressing cells. Genesis. 2011;49:797–802. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lasagni L., Ballerini L., Angelotti M.L. Notch activation differentially regulates renal progenitors proliferation and differentiation toward the podocyte lineage in glomerular disorders. Stem Cells. 2010;28:1674–1685. doi: 10.1002/stem.492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen A., Sheu L.F., Ho Y.S. Experimental focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in mice. Nephron. 1998;78:440–452. doi: 10.1159/000044974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kastner S., Wilks M.F., Gwinner W. Metabolic heterogeneity of isolated cortical and juxtamedullary glomeruli in adriamycin nephrotoxicity. Ren Physiol Biochem. 1991;14:48–54. doi: 10.1159/000173387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soose M., Haberstroh U., Rovira-Halbach G. Heterogeneity of glomerular barrier function in early adriamycin nephrosis of MWF rats. Clin Physiol Biochem. 1988;6:310–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iversen B.M., Amann K., Kvam F.I. Increased glomerular capillary pressure and size mediate glomerulosclerosis in SHR juxtamedullary cortex. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:F365–F373. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1998.274.2.F365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Verani R.R., Hawkins E.P. Recurrent focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: a pathological study of the early lesion. Am J Nephrol. 1986;6:263–270. doi: 10.1159/000167173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hann B.D., Baldelomar E.J., Charlton J.R. Measuring the intrarenal distribution of glomerular volumes from histological sections. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016;310:F1328–F1336. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00382.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baldelomar E.J., Charlton J.R., Beeman S.C. Phenotyping by magnetic resonance imaging nondestructively measures glomerular number and volume distribution in mice with and without nephron reduction. Kidney Int. 2016;89:498–505. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roeder S.S., Stefanska A., Eng D.G. Changes in glomerular parietal epithelial cells in mouse kidneys with advanced age. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2015;309:F164–F178. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00144.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ihara G., Kiyomoto H., Kobori H. Regression of superficial glomerular podocyte injury in type 2 diabetic rats with overt albuminuria: effect of angiotensin II blockade. J Hypertens. 2010;28:2289–2298. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32833dfcda. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sofue T., Kiyomoto H., Kobori H. Early treatment with olmesartan prevents juxtamedullary glomerular podocyte injury and the onset of microalbuminuria in type 2 diabetic rats. Am J Hypertens. 2012;25:604–611. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2012.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mirandola L., Apicella L., Colombo M. Anti-Notch treatment prevents multiple myeloma cells localization to the bone marrow via the chemokine system CXCR4/SDF-1. Leukemia. 2013;27:1558–1566. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xie J., Wang W., Si J.W. Notch signaling regulates CXCR4 expression and the migration of mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Immunol. 2013;281:68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anders H.J. Immune system modulation of kidney regeneration—mechanisms and implications. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2014;10:347–358. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2014.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kosan C., Godmann M. Genetic and epigenetic mechanisms that maintain hematopoietic stem cell function. Stem Cells Int. 2016;2016:5178965. doi: 10.1155/2016/5178965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rizzo P., Novelli R., Benigni A. Inhibiting angiotensin-converting enzyme promotes renal repair by modulating progenitor cell activation. Pharmacol Res. 2016;108:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rizzo P., Perico N., Gagliardini E. Nature and mediators of parietal epithelial cell activation in glomerulonephritides of human and rat. Am J Pathol. 2013;183:1769–1778. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun Y.B., Qu X., Zhang X. Glomerular endothelial cell injury and damage precedes that of podocytes in adriamycin-induced nephropathy. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55027. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jeansson M., Bjorck K., Tenstad O. Adriamycin alters glomerular endothelium to induce proteinuria. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:114–122. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007111205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu S., Ko Y.S., Teng M.S. Adriamycin-induced cardiomyocyte and endothelial cell apoptosis: in vitro and in vivo studies. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34:1595–1607. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2002.2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Waldschmidt J.M., Simon A., Wider D. CXCL12 and CXCR7 are relevant targets to reverse cell adhesion-mediated drug resistance in multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2017;179:36–49. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anders H.J., Vielhauer V., Schlondorff D. Chemokines and chemokine receptors are involved in the resolution or progression of renal disease. Kidney Int. 2003;63:401–415. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sayyed S.G., Gaikwad A.B., Lichtnekert J. Progressive glomerulosclerosis in type 2 diabetes is associated with renal histone H3K9 and H3K23 acetylation, H3K4 dimethylation and phosphorylation at serine 10. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:1811–1817. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Allam R., Pawar R.D., Kulkarni O.P. Viral 5′-triphosphate RNA and non-CpG DNA aggravate autoimmunity and lupus nephritis via distinct TLR-independent immune responses. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:3487–3498. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McCloy R.A., Rogers S., Caldon C.E. Partial inhibition of Cdk1 in G2 phase overrides the SAC and decouples mitotic events. Cell Cycle. 2014;13:1400–1412. doi: 10.4161/cc.28401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mulay S.R., Thomasova D., Ryu M. Podocyte loss involves MDM2-driven mitotic catastrophe. J Pathol. 2013;230:322–335. doi: 10.1002/path.4193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ronconi E., Sagrinati C., Angelotti M.L. Regeneration of glomerular podocytes by human renal progenitors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:322–332. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008070709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sagrinati C., Netti G.S., Mazzinghi B. Isolation and characterization of multipotent progenitor cells from the Bowman’s capsule of adult human kidneys. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2443–2456. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006010089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(A) Immunostaining for secondary antibodies as control for the double staining of Figure 1A (CXCL-12+Podocin+DAPI). Goat anti mouse IgG1 (the secondary antibody of CXCL-12) in green, goat anti-rabbit IgG (the secondary antibody of Podocin) in red and DAPI in white. Scale bar= 20 μm. (B) Immunostaining for CXCR4 and CXCR7 in Adriamycin nephropathy of Balb/cAncrl mice. Representative images are shown of healthy and injured glomeruli at different time points as indicated. Arrows point positive cells on Bowman’s capsule. Scale bar = 25 μm. (C) CXCL12 inhibition in healthy animals showed no significant variation in the albumin/creatinine urinary ratio after 2 weeks of treatment. n = 6 per group. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. (D) No major glomerular lesions were found in the endpoint day 14 after treatment with the inhibitor compared with the control (representative pictures). n = 6 for group. Scale bars = 20 μm. (E) PAS-stained sections of Balb/cAncrl mice with Adriamycin-induced nephropathy treated with control or NOX-A12. Scale bars = 100 μm.

Pax2 immunostaining on mouse sections. (A,B) Pax2 immunostaining (blue) was performed on sections of healthy (A) and ADR+NOX-A12 (B) Pax2.rtTA;TetO.Cre;mT/mG mice. DAPI counterstains nuclei. Arrows point EGFP+ cells that were also positive for Pax2-antibody (green/blue cells) in the glomerulus. Arrowheads point to cells inside the tuft that are positive for Pax2-antibody but EGFP-. Asterisk points a Pax2-derived podocyte inside the tuft that is negative for Pax2-antibody. Bars = 20 μm.

Immunostaining for Notch in Balb/cAncrl mice. The Notch intracellular domain (NICD)-3 is stained in green, nephrin in red, and To-pro-3 in blue in mice with adriamycin (ADR)-induced nephropathy treated with the CXCL12 inhibitor NOX-A12 or inactive control. Note that CXCL12 inhibition induces Notch also inside the glomerulus, namely in PECs. Representative images are shown. Scale bar = 20 μm.

STED super-resolution microscopy reveals Pax2+PEC–derived cells (EGFP+, green) within the tuft (tdTomato, red) of an Adriamycin Pax2.rtTA;TetO.Cre;mT/mG mouse treated with NOX-A12. These cells displayed all structural features of fully differentiated podocytes and fully integrated into the glomerular filtration barrier.

Pax2+PECs of the Bowman’s capsule generate new podocytes (green) in the injured tuft (red) of an Adriamycin Pax2.rtTA;TetO.Cre;mT/mG mouse treated with NOX-A12. Red and white signals (td Tomato and DAPI, respectively) are virtually removed along the y axis in order to better show the Pax2+PEC–derived cells (green) inside the tuft.