Abstract

Punica species are medicinally important plants belonging to the family Lythraceae. The pomegranate is widely reported to exhibit antiviral, antioxidant, anticancer, anti-proliferative activities. In the present study the ethanolic extract of the peel seeds of two species of Punica (Punica granatum and Punica protopunica) were subjected to GC–MS analysis. Twenty-one and 14 compounds were identified in P. granatum and P. protopunica peel seeds, respectively. The main chemical constituents in P. granatum-peel seeds were propanoic acid, benzenedicarboxylic acid, methoxypropionic acid and methyl amine. The corresponding constituents of P. protopunica peel seeds were benzenedicarboxylic acid, benzoic acid and propanoic acid. Moreover, the antioxidant effects of the aqueous ethanolic extracts were estimated in vitro. The two tested extracts contained significantly different phenolic and total flavonoid contents in P. granatum than in P. protopunica. Different in vitro methods of antioxidant activity determination produced varying results. In malondialdehyde (MDA), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) scavenging and 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) assays, the two peel seed extracts exhibited very high antioxidant activities, with higher activity observed for the P. granatum extract.

Keywords: Punica species, GC–MS analysis, Bioactive compounds, Antioxidants

1. Introduction

Traditional medicine is the sum total of knowledge, skills and practices based on theories, beliefs and experiences indigenous to different cultures that are used to maintain health and also, to prevent, diagnose, improve or treat physical and mental illness (www.who.int/medicines/areas/traditional/definitions/en/). Various types of traditional medicine and other medical practices referred to as complementary or alternative medicine are increasingly used in both developing and developed countries. Punica sp. (Punicaceae), recently described as nature’s power fruit, are plants used in folkloric medicine for the treatment of various diseases (Abdel Moneim et al., 2011, Ajaikumar et al., 2005) and are widely cultivated in the Mediterranean region. Punica sp. are cultivated in Iran, California, Turkey, Egypt, Italy, India, Chile and Spain. The world pomegranate production amounts to approximately one and a half million tons (FAOSTAT http://www.fao.org), and the peel accounts for approximately 60% of the total weight (Lansky and Newman, 2007).

Punica granatum L. commonly known as the pomegranate is one of the most important and oldest edible fruits of tropical and subtropical regions. It originated in the Middle East and India and has been used for centuries in ancient cultures for its medicinal purposes. Pomegranate has been widely reported to exhibit antiviral, antioxidant, anticancer and anti-proliferative activities (Faria et al., 2006, Faria et al., 2007, Adhami and Mukhtar, 2006, Adhami and Mukhtar, 2007). The pomegranate is a symbol of life, longevity, health, femininity, fecundity, knowledge, morality, immortality and spirituality; if not divinity (Lansky and Newman, 2007).

Punica protopunica commonly known as the pomegranate tree or Socotran pomegranate, is a species of flowering plant in the Lythraceae family that is endemic to the island of Socotra (Yemen). It differs from the pomegranate in having pink (not red), trumpet-shaped flowers and smaller, less sweet fruit. The fruit when ripe is yellow-green or brownish red in color. P. granatum L is considered to have originated in the region of Iran to northern India, and has been cultivated since ancient times. It is widely cultivated throughout the Mediterranean region of southern Europe, the Middle East and Caucasus region, northern Africa and tropical Africa, the Indian subcontinent, Central Asia, and the drier parts of southeast Asia. P. granatum L. has an especially wide variety of activities. Its fruits contain secondary metabolites such as alkaloids, flavonoids, steroids, phenolics, terpenes, volatile oils, mineral elements, amino acids glycosides and sterols (Yoshikazu et al. (2001).

Gas chromatography mass spectroscopy, is the most commonly used technique for identification and quantification of compounds in extracted samples. The unknown organic compounds in a complex mixture can be determined by interpretation from matching the spectrum with reference spectra (Ronald Hites, 1997). The objective of the present study was to compare the phytochemical constituents of the ethanolic extract of P. granatum and P. protopunica peel seeds using the GC–MS technique, particularly antioxidants, which are substances that markedly delay or prevent the oxidation of oxidizable substrate when present in foods or the body at low concentrations.

Antioxidants may help the body to protect itself against various types of oxidative damage caused by reactive oxygen species, which are associated with a variety of diseases including cardiovascular diseases, cancers (Gerber et al., 2002), neurodegenerative diseases and Alzheimer’s disease (Di-Matteo and Exposito, 2003). Natural plant antioxidants can therefore be used as a type of preventive medicine. Dietary phenolic compounds and flavonoids have generally been considered, as non-nutrients and their beneficial effect on human health has only recently been recognized. Flavonoids are known to possess anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antiallergic, hepatoprotective, antithrombotic, neuroprotective, and anticarcinogenic activities (Araceli et al., 2003). Phenolic compounds may contribute directly to antioxidant activity because of the presence of hydroxyl functional groups around the nuclear structure that are potent hydrogen donators. These phenolic compounds of plant origin show antioxidant effects by various mechanisms including the ability to scavenge free radicals, chelate metal ions that serve as catalysts for the production of free radicals, and activate various antioxidant enzymes and inhibit oxidases (Kulkarni et al., 2004).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Collection of plant material

The fresh fruits of the two species of P. granatum and P. protopunica were collected from markets in Riyadh. The selected fruits were identified and authenticated in the Botany and Microbiology Department of Science College at King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

2.2. Chemicals reagents

Thiobarbituric acid, D-catechin, quercetin, DPPH and 1,1,3,3-tetraethoxypropane were obtained from Sigma–Aldrich, UK. All other reagents used in this experiment were obtained from BDH.

2.3. Extraction

All seeds were washed with tap water. A portion of each sample was weighed (300–400 g) and 1500 ml of the extracting solvent (80% ethanol) was added. The extraction was conducted at 80 °C for approximately 30 min, and the extract was filtered through cotton wool. The residue was extracted again using 1000 ml of the same extracting solvent for approximately 5 min in a boiling water bath, left overnight in the refrigerator and filtered through a cotton wool plug in the neck of the filter funnel. The two extracts were combined and evaporated using a rotary evaporator apparatus under vacuum at 40 °C until no more water could be distilled. The obtained heavy extract was weighed and stored at −80 °C to be used for further studies.

2.4. Determination of total phenolic compounds

The amount of total phenolic compounds in the ethanolic extract was expressed as the D-catechin equivalent (mg CE/100 g seed extract). Each extract (5 g) was initially dissolved in distilled water and the volume was then adjusted to 25 ml. The total phenolic contents were measured according to the method described by Singleton and Rossi (1965). Briefly, 0.1 ml of the solution was added to 0.5 ml of Folin–Ciocalteau reagent and mixed for 1 min and then 1 ml sodium carbonate solution (0.08 g/ml) was added. The volume was then adjusted to 2 ml with distilled water and the solution was mixed again. The mixture was left for 1 h at room temperature in a dark place and the absorbance was measured at 760 nm using a UV/VIS spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, UV-1601). Measurements were taken in triplicates. The calibration curve of D-catechin was prepared by using concentrations from 50 to 400 μg/100 ml and the concentration of each sample was calculated from the D-catechin standard curve.

2.5. Determination of total flavonoids

The aluminum chloride colorimetric method was used for flavonoid determination and expressed as quercetin equivalent (mg/100 g seed extract) as described by Chang et al. (2002). 0.1 ml of each extract (10 mg/ml) in methanol was separately mixed with 1.5 ml of methanol, 0.1 ml of 10% AlCl3, 0.1 ml of 1 M CH3COOK and 2.8 ml of distilled water and kept at room temperature for 30 min. The absorbance of the reaction mixture was measured at 415 nm. A calibration curve for quercetin was prepared by using concentrations from 12.5 to 100 μg/ml in methanol, and the total flavonoids were expressed as the quercetin equivalent (mg QE/100 g seed extract).

2.6. Total antioxidant activity of Punica sp. extract determined using the TBARS method

The thiobarbituric acid reactive species method was used as described by Duh et al. (2001) with slight modifications to measure the total antioxidant activity. Briefly, this method was conducted using the homogenate (10%) in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) as a lipid rich medium. A stock solution of each extract in methanol (1 mg/ml) was prepared, different volumes (50, 100, 300, and 500 μl) from each stock solution were transferred into test tubes and the volumes were adjusted to 1 ml using the same solvent. Lipid peroxidation was initiated by adding 4.0 ml of ferric chloride (400 mM) and 40 μl of L-ascorbic acid (200 mM), followed by incubation for 1 h at 37 °C. After incubation, 3 ml of 0.25 N HCl containing 15% trichloro acetic acid and 0.375% thiobarbituric acid was added. The reaction mixture was boiled for 30 min, cooled, and then centrifuged at 2000 g for 5 min. A blank was prepared with the same reagents without a sample extract, and using vitamin C as a positive control (100 μg/ml). The absorbance was measured at 532 nm and a decrease of absorbance indicated an increase in antioxidant activity. The antioxidant activity was expressed as the percentage inhibition of lipid peroxidation as follows:

where Ab is the absorbance of the blank and As is the absorbance of the sample or positive control (Test with a known result. This result is usually what researchers expect from the treatment, so it gives them something to compare).

2.7. Total reducing power ability (TRPA)

The total reducing power of the samples was determined according to the method described by Oyaizu (1986). A stock solution of each extract in methanol (1 mg/ml) was prepared and different volumes (50, 100, 300, and 500 μl) from each stock solution were transferred to test tubes and the volume in each test tube was adjusted to 1 ml with the same solvent. Then, 2.5 ml of 200 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.6), and 2.5 ml of 1% potassium ferricyanide were added to each test tube and incubated at 50 °C for 20 min. After incubation, 2.5 ml of 10% trichloroacetic acid was added and the mixture was centrifuged at 2000g for 10 min. The upper layer in each tube (2.5 ml) was mixed with 2.5 ml of deionized water and 0.5 ml of 0.1% ferric chloride. The absorbance was measured at 700 nm against a blank. The reducing power increases with the increase in absorbance. The total reducing power ability of each extract at different concentrations was compared to vitamin C as a positive control and the results were expressed as the vitamin C equivalent (l M).

2.8. DPPH radical scavenging activity

The antioxidant activities of the extracts were measured in terms of hydrogen donating or radical scavenging ability using the stable radical DPPH (Brand-Williams et al., 1995). A methanolic stock solution of each sample was prepared to a concentration of 1 mg/ml. Different volumes (50, 100, 300, and 500 μl) of the stock solution were transferred to test tubes and the volume was adjusted to 1 ml using the same solvent. DPPH (2 ml; 0.06 M in methanol) was added to each test tube. A positive control (vitamin C, 100 μg/ml) was prepared in the same way as the samples. Finally, a solution containing only 1 ml of methanol and 2 ml of DPPH solution was prepared and used as a blank. All test tubes were incubated in a dark place at room temperature for 1 h. The spectrophotometer was set at 517 nm and the absorbance was adjusted to zero for methanol. The absorbance of the blank, positive control, and samples was recorded. The disappearance of DPPH was recorded and the percent inhibition of the DPPH radical by the samples and the positive control was calculated as follows:

where Ab is the absorbance of blank (has the highest value) and As is the absorbance of a sample or the positive control.

2.9. Preparation and extraction for GC–MS analysis

The peeled seeds of the two studied species P. granatum and P. protopunica were shade dried. The dried seeds were then pulverized to a powder using a mechanical grinder and the powders were preserved in an air sealed polythene cover. The powder (100 g for each) was macerated in ethanol for 5 days with occasional stirring and the extracts were filtered using Whatman No. 1 filter paper. The residues obtained after the filtration extraction were again extracted in methanol by the Soxhlet method. The extracts were taken and filtered. The crude extracts obtained were concentrated under reduced pressure in a rotary evaporator at 40 °C and used for GC–MS analysis.

2.10. Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) analysis

GC–MS analysis was conducted on a Perkin Elmer Turbo mass spectrophotometer (Norwalk, CTO6859, and USA) which included a Perkin Elmer XLGC. The column used was a Perkin Elmer Elite-5 capillary column measuring 30 × 0.25 mm with a film thickness of 0.25 mm and composed of 95% dimethyl polysiloxane. The carrier gas used was helium at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. A 1 μl sample injection volume was utilized. The inlet temperature was maintained as 250 °C. The oven temperature was programed initially at 110 °C for 4 min, then increased to 240 °C. Then, the temperature was programed to increase to 280 °C at a rate of 20 °C ending with a 5 min period. The total run time was 90 min. The MS transfer line was maintained at a temperature of 200 °C. The source temperature was maintained at 180 °C. The GC–MS was analyzed using electron impact ionization at 70 eV and the data were evaluated using total ion count (TIC) for compound identification and quantification. The spectra of the components were compared with the database of spectra of known components stored in the GC–MS library. Measurement of peak areas and data processing was conducted by using the database of the WILEY-275 and FAME Libraries. The names, molecular weights and structure of the components of the test materials were thereby ascertained.

3. Results and discussion

The total phenolic contents for P. granatum was 632.5 mg as D-catechin equiv./100 g seed, and the total flavonoids content for the same samples was 361.8 as quercetin equiv./100 g seed. For P. protopunica, the total phenolic compound and flavonoid contents were 409.4 and 201 mg D-catechin equiv./100 g, respectively. The present results (Table 1) show that the P. granatum extract had higher amounts of both total phenolics and total flavonoids. However, the ratio of total flavonoids/total phenolics (0.49–0.57) in the present samples indicates a high content of flavonoids (Table 1).

Table 1.

Total phenolics, total flavonoids and total flavonoids/total phenolics in Punica granatum and Punica protopunica. Values are the mean of 3 replicates ± SD.

| Species | Total phenolic content (mg/100 g) | Total flavonoid content (mg/100 g) | Total flavonoids/phenolics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Punica granatum | 632.5 ± 4.54 | 361.8 ± 4.22 | 0.57 |

| Punica protopunica | 409.4 ± 3.15 | 201 ± 2.10 | 0.49 |

The ratio of the total flavonoids to the total phenolics was in the range of 0.49–0.57%, which means that the flavonoids may be primarily responsible for the biological activity because flavonoids especially those having hydroxyl groups are potent hydrogen donors (•H) and consequently can easily neutralize free radicals.

The total antioxidant activity of the two Punica extracts against lipid peroxidation was expressed as the percent inhibition of TBARS formation (Table 2). The data showed that all extracts had antioxidant activity, as they inhibited lipid peroxidation in a concentration dependent manner. Thus, the results of TBARS obtained from the lowest and the second levels of the extract show that the P. granatum extract had significantly higher activity in preventing lipid peroxidation than the other extract. However, at higher levels all extracts and the positive control showed almost the same ability to prevent lipid peroxidation. All extracts showed almost complete inhibition of lipid peroxidation that was not significantly different from the results of the positive control. These results are in agreement with many studies that attributed the antioxidant activity to the presence of phenolic and polyphenolic compounds in various plants (Gazzani et al., 1998), fruits (Meyer et al., 1998), and medicinal plants (Vinson et al., 1995).

Table 2.

Phytochemicals identified in the ethanolic extracts of P. granatum peel seeds by GC–MS.

| PK | RT | Area | DATABASE/Wiley 275.1 Library/ID/ |

Ref. | CAS | Qual. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.96 | 17.04 | Benznepropanoic acid, .beta.-oxo Silane, fluorotrimethyl-(CAS) $$ 2-methyl-4-methylthio-2,3dihydrot | 75860 | 000094-02-0 | 36 |

| 4514 | 000420-56-4 | 25 | ||||

| 29049 | 000000-00-0 | 17 | ||||

| 2 | 3.26 | 6.49 | 2-propanol, 1-(propylthio)-(CAS) Ethanol (CAS) $$ Ethyl alcohol $$ Methyl ester of 3-methoxypropionic | 22819 | 053957-22-5 | 50 |

| 281 | 000064-17-5 | 40 | ||||

| 13974 | 003852-09-3 | 37 | ||||

| 3 | 3.36 | 5.90 | Ethanol (cas) $$ethyl alcohol $$ Acetic acid, methoxy-, methyl ester Ethanol (CAS) $$ Ethylalcohol $$ | 273 | 000064-17-5 | 47 |

| 8140 | 006290-49-9 | 43 | ||||

| 283 | 000079-17-5 | 38 | ||||

| 4 | 6.28 | 2.15 | Acetic acid, chloro-, ethyl ester 4,4-Di-trideuteromethyl-2-allylcyc Acetamide,2-chloro-, (CAS) $$Micr | 15399 | 000105-39-5 | 12 |

| 51693 | 000000-00-0 | 10 | ||||

| 4624 | 000079-07-2 | 9 | ||||

| 5 | 6.66 | 5.27 | Norepinephrine-pentatms $$ Silanam 1-propene,3,3-dichloro-(CAS) $$ 1,3-Isobenzofurandione, 4-nitro-( | 263121 | O56114-59-5 | 10 |

| 9571 | 000000-00-0 | 9 | ||||

| 76903 | 000079-07-2 | 9 | ||||

| 6 | 9.46 | 0.80 | Methyl ester of tri-o-methylisopho Trans-1,3-Bis(trideuterioacetamido Cis-1-nitro-1-propene | 248558 | 071295-04-0 | 22 |

| 112131 | 070925-27-8 | 10 | ||||

| 3615 | 027675-36-1 | 9 | ||||

| 7 | 9.78 | 1.70 | 17.beta.-acetoxy-4-oxo-4-propyl-3,17.beta.-acetoxy-1.alpha.-carboeth 1OH-phenoxazine,2,4,6,8-tetrakis( | 241520 | 000000-00-0 | 9 |

| 241521 | 000000-00-0 | 7 | ||||

| 237561 | 055649-30-4 | 5 | ||||

| 8 | 9.91 | 2.34 | 2-Furanmethanol (CAS) $$ furfuryl 2-Furanmethanol (CAS) $$ furfuryl Sulfuric acid , diethyl ester (CAS) | 5545 | 000098-00-0 | 22 |

| 5544 | 000098-00-0 | 10 | ||||

| 39149 | 000064-67-5 | 10 | ||||

| 9 | 12.22 | 3.83 | 2(3H)-Benzofuranone, 3-(3-methoxy- Estr-5(10)-en-17-ol,3-fluoro-,ac 1-Bromo-4,4-dimethyl-5-methylen-2, | 193019 | 023670-24-8 | 11 |

| 193161 | 022034-57-7 | 11 | ||||

| 243790 | 078366-42-4 | 10 | ||||

| 10 | 12.69 | 5.66 | 1H-pyrrole-2,5-dione, 3-methyl-4-(Mitomycin B $$ Azirino(2’,3’:3,4) p 2-(n-benzyl-n-methylamino)-5(4)-T- | 211057 | 055268-59-2 | 9 |

| 210881 | 004055-40-7 | 9 | ||||

| 211055 | 057053-60-8 | 7 | ||||

| 11 | 13.79 | 3.98 | (6E,2R,3S,5RS)-5-(phenylsulfonyl)- Bis(z)-but-2-en-1,4-diol(1,1,1,5 Decafluorobis (trifluoromethyl)-cyc | 226436 | 128329-34-0 | 1 |

| 257457 | 091030-20-5 | 1 | ||||

| 234539 | 000000-00-0 | 1 | ||||

| 12 | 14.01 | 2.84 | 8,10-cyclo-2,5,12,18-tetramethyl-3 (3-(Benxoyloxy)-1,4-diphenyl-2-nap 3,4,17-tris (trimethylsilyloxy)-est | 260223 | 000000-00-0 | 49 |

| 260230 | 092012-83-4 | 38 | ||||

| 260146 | 000000-00-0 | 25 | ||||

| 13 | 15.16 | 5.45 | 1-propene,1,1-dichloro-(CAS) $$ 1,2,3,6-Tetrahydro-2-pyridone Hexaachlorobenzene | 9553 | 000563-58-6 | 12 |

| 5374 | 000000-00-0 | 10 | ||||

| 168006 | 000000-00-0 | 10 | ||||

| 14 | 17.38 | 4.65 | 8-(Acetoxymethyl)-6,9-dichloro-5-hy Trans-1-(3S,2,2-Trimethyl-1-indany 11-(N-acetyl)piperidin-4-ylidene | 190014 | 078076-81-0 | 9 |

| 190672 | 096144-93-3 | 9 | ||||

| 190441 | 000000-00-0 | 9 | ||||

| 15 | 17.87 | 4.73 | 4,4-Dimethyl-5-ethylcyclopent-2-en (−)-(3aR,6aS)-3,3a,6,6a-Tetrahydro 2-Aminopyrazine $$ Aminopyrazine $ | 26394 | 081825-20-9 | 38 |

| 16574 | 043119-93-4 | 14 | ||||

| 4926 | 005049-61-6 | 9 | ||||

| 16 | 18.32 | 2.68 | 18.alpha.,24-Dihydroxy-A(1)-norlup Fluorene-2-carbonitrile, 9-(triphe (acetaldoximato-N,o) carbonylbis(di | 256919 | 075808-76-3 | 10 |

| 250537 | 007293-78-9 | 9 | ||||

| 260785 | 124402-11-5 | 7 | ||||

| 17 | 19.13 | 6.12 | 1,3-dibutylurea | 57175 | 000000-00-0 | 5 |

| 18 | 21.01 | 1.57 | No matches found | |||

| 19 | 24.94 | 11.32 | 1,2-benzenedicarboxylic acid, bis(Di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate 1,2-benzenedicarboxylic acid, bis( | 230979 | 000117-81-7 | 80 |

| 231010 | 000117-81-7 | 80 | ||||

| 230983 | 000117-81-7 | 80 | ||||

| 20 | 26.17 | 3.24 | 4′methyl-2 phenylindole N-methyl-2-iodo-pyrrole 1,4-benzendiol,2,5-bis(1,1-dimet | 92601 | 000000-00-0 | 10 |

| 92072 | 000000-00-0 | 10 | ||||

| 107904 | 000088-58-4 | 10 | ||||

| 21 | 33.10 | 2.23 | Progesterone bis-t-boms oxime 1,3,4,6,7-pentaphenythieno (3,4-c) 4,5-Dihydroxy-7-methoxyanthraquino | 266946 | 000000-00-0 | 9 |

| 261586 | 087612-94-0 | 7 | ||||

| 263212 | 000000-00-0 | 4 |

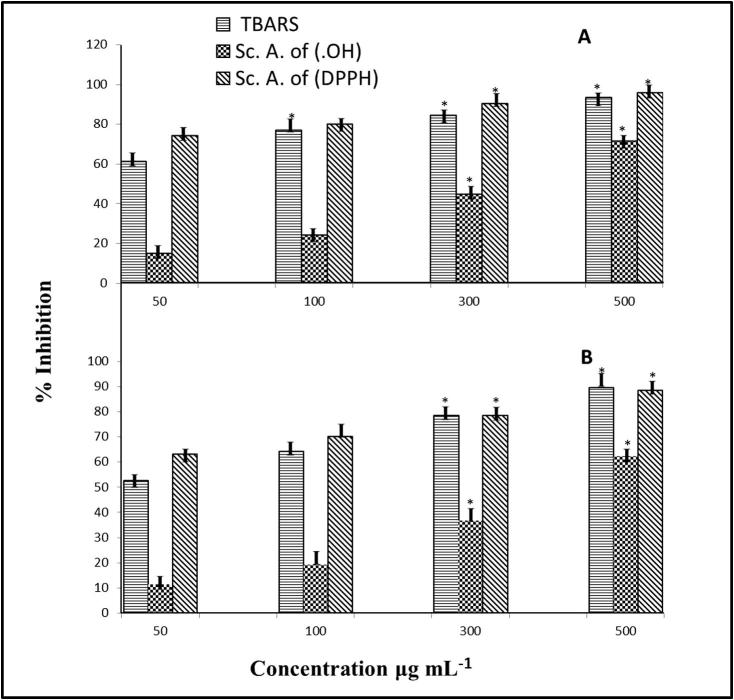

The hydroxyl radical scavenging activities of both ethanolic Punica sp. extracts were noted as low to intermediate and increased in a concentration dependent manner (Fig. 1). This study therefore confirmed that Punica extracts are active scavengers of hydroxyl radicals, which cause damage to DNA. All extracts had significantly lower •OH radical scavenging activity than the positive control, but at the highest concentrations, the P. granatum extract showed significantly higher •OH radical scavenging activity than the P. protopunica extract. In this study, all extracts had significantly lower •OH radical scavenging activity than the positive control, but at the highest concentrations, the P. granatum extract showed significantly higher •OH radical scavenging activity than the P. protopunica extract. Hydroxyl radicals (•OH) is an extremely reactive free radical formed in biological systems that may cause serious damage by damaging the biomolecules of living cells. •OH has the capacity to break DNA strands, which contributes to carcinogenesis, mutagenesis, and cytotoxicity. In addition, this radical species is thought to be one of most rapid initiators of the lipid peroxidation process, abstracting hydrogen atoms from unsaturated fatty acids (Bloknina et al., 2003).

Figure 1.

Antioxidant capabilities [TBARS, Thiobarbituric acid reactive species method; Sc.A. of (NO), nitric oxide (NO) scavenging activity and Sc.A. of (DPPH), radical scavenging effects of the extract on DPPH free radical] of Punica granatum (A) and Punica protopunica extracts. Data are presented as the mean ± SE (n = 3). *Significantly correlated (p ⩽ 0.05).

The present study has shown that the extract from the two Punica sp. exhibited strong DPPH scavenging activity (Fig. 1), where an increase in the extract concentration resulted in a significant decrease in the concentration of DPPH because of the free radical scavenging effect of the extract. Because the hydrogen donation of the tested extract was comparable to that of vitamin C, it is evident that the extract could serve as a hydrogen donor and consequently terminate the radical chain reaction. The tests to evaluate the reducing ability of the Punica extracts were conducted on the basis of the oxidizability of their chemical constituents, such as phenolic and polyphenolic compounds, which could reduce Fe3+ to Fe2+ ions.

Data can be explained on the bases of other studies (Conforti et al., 2005) that relate the hydrogen donation ability using the DPPH method to the presence of phenolic and polyphenolic compounds. In the presence of hydrogen donors, DPPH• is oxidized, and a stable free radical is formed from the scavenger.

Gas chromatography mass spectroscopy analysis was conducted on the crude ethanolic extract of the peel seeds from two Punica species. The peaks in the chromatogram were integrated and compared with the database of spectra of known components (Wily-275) stored in the GC–MS library. Detailed tabulations of the GC–MS analysis of the extracts are given in Table 2, Table 3. Phytochemical by GC–MS analysis of the studied Punica species revealed the presence of different fatty acids, heterocyclic compounds etc.

Table 3.

Phytochemicals identified in the ethanolic extracts of P. protopunica peel seeds by GC–MS.

| PK | RT | Area | DATABASE/Wiley 275.1 Library/ID |

Ref. | CAS | Qual. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.98 | 24.05 | Benzoic acid (CAS) $$ Retardex $$ | 15541 | 000065-85-0 | 36 |

| Propanoic acid, 2-hydroxy-,ethyl | 13968 | 000097-64-3 | 25 | |||

| Formic acid, ethyl ester (CAS) $$ | 1698 | 000109-94-4 | 25 | |||

| 2 | 3.29 | 6.62 | Silane,diethoxydimethyl-(CAS) $$ | 33589 | 000078-62-6 | 42 |

| Propanoic acid, 2-hydroxy-2-indenone | 13970 | 000097-64-3 | 38 | |||

| 3-phenyl-6,7-dicarboxy-2-indenone | 173210 | 092241-98-0 | 23 | |||

| 3 | 3.38 | 6.98 | Dimethlamine – D1 | 238 | 000917-72-6 | 47 |

| Propanoic acid,2-hydroxy-,ethyl | 13970 | 000097-64-3 | 47 | |||

| Benzoic acid,3,5dimethyl-,(3,5- | 151791 | 055000-47-0 | 43 | |||

| 4 | 6.66 | 1.87 | Sulfonium, dimethyl(4-nitropheny | 145423 | 031657-43-9 | 10 |

| Benzonitrile,4-methoxy- (CAS) $$ | 22457 | 000874-90-8 | 9 | |||

| 2-oxo-2,4-dithiapentane | 16319 | 000000-00-0 | 9 | |||

| 5 | 9.91 | 3.06 | N,N′-Dithiobissuccinimide $$2,5-p | 143603 | 034251-41-7 | 47 |

| Propanoic acid ,2-chloro- (CAS) $$ | 8914 | 000598-78-7 | 9 | |||

| 3-methylsulfinyl-3-methylbutan-1-0 | 35043 | 000000-00-0 | 9 | |||

| 6 | 12.69 | 3.04 | 4-Methoxy-N-(2-methoxyphenyl)-7-me | 240338 | 106911-45-9 | 10 |

| 5.alpha.-Cholestan -7.beta.-amine, | 240489 | 001254-01-9 | 9 | |||

| Cholestan-7-amine, N,N-dimethyl-( | 240488 | 055331-89-0 | 9 | |||

| 7 | 15.16 | 2.33 | 2-Nonadecanone 2,4-dinitrophenyhy | 253076 | 000000-00-0 | 9 |

| 2-Nonadecanone 2,4-dinitrophenylhy | 253075 | 000000-00-0 | 9 | |||

| 2-Nonadecanone 2,4-D.N.P.H. | 253074 | 000000-00-0 | 9 | |||

| 8 | 17.40 | 3.51 | 1,3,5-Triazine, 2- (2-methoxypheny | 250424 | 024478-02-2 | 16 |

| Ankorine | 202820 | 056816-22-9 | 14 | |||

| Strychnine $$ strychnidin-10-one | 202380 | 000057-24-9 | 10 | |||

| 9 | 17.87 | 6.77 | Bicyclo (4.1.o) heptane, 7- butyl- (c | 38520 | 018645-10-8 | 32 |

| 1-isopropenyl-4-methylcyclohexanec | 51635 | 116927-18-5 | 22 | |||

| (12z)-7.beta.-acetoxy.- acetoxy-8-hydroxy-6. | 250271 | 111554-91-7 | 22 | |||

| 10 | 18.32 | 4.04 | 1-Butyl-1-hydridotetrachlorocyclot | 201338 | 071982-87-1 | 10 |

| PHOSPHORAMIDOTHIOIC ACID ,T-BUTYL- | 172308 | 000000-00-0 | 10 | |||

| Methylenetanshinquinone | 160393 | 067656-29-5 | 10 | |||

| 11 | 19.13 | 3.51 | 1,3,2-dioxaphospholane,2,4,5-trim | 22747 | 000000-00-0 | 27 |

| 1,3-Propanediol, 2-methyl-2-propyl | 102759 | 000057-53-4 | 12 | |||

| Cyclopentanone, 2-chloro- (CAS) $$ | 13884 | 000694-28-0 | 12 | |||

| 12 | 19.42 | 4.09 | Tris (5-methyl-1,3,2-benzodithiabor | 260782 | 053484-09-6 | 18 |

| N-N-dimethylaetioporphyrin I $$ 2 | 260710 | 056630-99-0 | 9 | |||

| N-N-dimethylaetioporphyrin I $$ 2 | 260709 | 056630-99-0 | 9 | |||

| 13 | 24.94 | 27.71 | Di-2 (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate | 231010 | 000117-81-7 | 86 |

| 1,2-Benzenedicarboxylic acid, bis ( | 230983 | 000117-81-7 | 86 | |||

| 1,2-Benzenedicarboxylic acid, diis | 230990 | 027554-26-3 | 86 | |||

| 14 | 31.84 | 2.42 | Dimethyl ester of 3,4,7-triphenyl- | 256382 | 061164-99-6 | 7 |

| 3.alpha.-chloro-4,4-dimethyl-3.bet | 256390 | 104461-25-8 | 3 | |||

| 6″,7″-Dimethyl-2′″ –phenyltrispi | 256393 | 072553-51-6 | 3 |

The comparison of the mass spectra with the database gave a match higher than 85% and a confirmatory compound structure match. The GC–MS analysis of the concentrated ethanol extract identified many compounds.

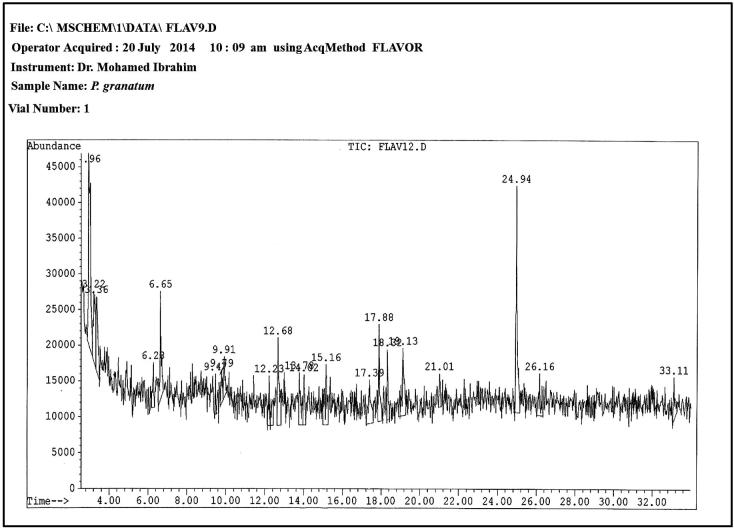

The GC–MS chromatogram of the ethanolic extract of P. granatum peel (Fig. 2) showed 21 peaks indicating the presence of twenty-six phytochemical constituents. Via comparison of the mass spectra of the constituents with the WILEY275 library, the twenty-one phytoconstituents were characterized and identified (Table 3). The major phytochemical constituents were benzenepropanoic acid, beta-oxo silane, 1,2-benzenedicarboxylic acid, bis (Di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate 1,2-benzenedicarboxylic acid, 2-propanol, 1-(propylthio)-(CAS) ethanol (CAS) ethyl alcohol methyl ester of 3-methoxypropionic; 1,3-dibutyl urea and 1H-pyrrole-2,5-dione, 3-methyl-4-(mitomycin B – azirino (2′,3′:3,4) p2-(N-benzyl-N-methyl amino).

Figure 2.

GC–MS chromatogram of ethanolic extract of Punica granatum seeds.

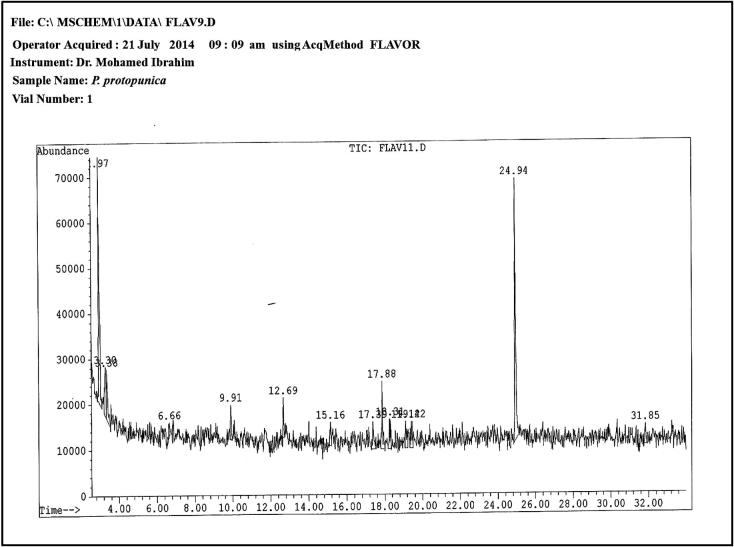

The P. protopunica seed extract showed 14 peaks in (Fig. 3) the GC–MS chromatogram indicating the presence of 14 phytochemical constituents. Through comparison with mass spectra 14 phytoconstituents were characterized and identified (Table 2). The major phytochemical constituents were Di-2 (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate 1,2-benzenedicarboxylic acid, bis (1,2-benzenedicarboxylic acid, benzoic acid (CAS) propanoic acid, 2-hydroxy-ethyl formic acid and benzoic acid (CAS) propanoic acid, and 2-hydroxy-formic acid.

Figure 3.

GC–MS chromatogram of ethanolic extract of Punica protopunica seeds.

Our results indicated that peel seeds of pomegranate could be considered as a highly valuable source of the antioxidants displaying higher activity as compared with ascorbic acid which was used as a positive control. The difference in the antioxidant activity of the two peel seeds in the two species may be attributed to their different phenolic and flavonoid compositions. It was mentioned that peels contained more phenolics than did flesh tissues (Negi and Jayaprakasha, 2003). Reddy et al. (2007) stated that total tannins and purified constituents (e.g., ellagic acid and punica lagins) of crude pomogranate possessed antioxidant activity and strongly inhibited ROS generation with IC50 of 0.33–11 μg/ml.

4. Conclusion

In all tested methods, the antioxidant activity of all Punica sp. was compared with that of vitamin C, which is a well-known potent antioxidant. In general, Punica sp. appear to be a good source of natural antioxidants. In the present study, 21 and 14 constituents were identified from the ethanolic extract of P. granatum peel and P. protopunica by GC–MS analysis, respectively. Many fatty acids were present in both extracts. The presence of various bioactive compounds justifies their use for the treatment of various ailments by traditional practitioners. Propanoic and benzoic acids were present in high amounts in seeds of both Punica species. Moreover, Punica sp. could be considered a powerful source of natural antioxidants.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to extend their sincere appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University for its funding of this research through the Research Group Project no RGP-VPP-231.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

References

- Abdel Moneim A.E., Mohamed A.D., Al-Quraishy S. Studies on the effect of pomegranate (Punica granatum) juice and peel on liver and kidney in adult male rats. J. Med. Plants Res. 2011;5(20):5083–5088. [Google Scholar]

- Adhami V.M., Mukhtar H. Polyphenols from green tea and pomegranate for prevention of prostate cancer. Free Radical Res. 2006;40(10):1095–1104. doi: 10.1080/10715760600796498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adhami V.M., Mukhtar H. Anti-oxidants from green tea and pomegranate for chemoprevention of prostate cancer. Mol. Biotechnol. 2007;37:52–57. doi: 10.1007/s12033-007-0047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajaikumar K.B., Asheef M., Babu B.H., Padikkala J. The inhibition of gastric mucosal injury by Punica granatum L. (pomegranate) methanolic extract. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005;96:171–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araceli S., Camen R.M., Guillermo R.S. Assessment of the anti-inflammatory activity and free radical scavenger activity of tiliroside. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2003;461(2003):53–61. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)02953-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloknina O., Virolainen E., Fagerstedt K.V. Antioxidants, oxidative damage, and oxygen deprivation stress. Ann. Bot. 2003;91:179–194. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcf118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand-Williams W., Cuvelier M.E., Berset C. Use of free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. Lebensm. Wiss. Technol. 1995;28:25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Chang C., Yang M., Wen H., Chern J. Estimation of total flavonoid content in propolis by two complementary colorimetric methods. J. Food Drug Anal. 2002;10:178–182. [Google Scholar]

- Conforti F., Loizzo M.R., Satti G.A., Menichini F. Comparative radical scavenging and antidiabetic activities of methanolic extract and fractions from Achillea ligustica. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2005;28(Suppl. 9):1791–1794. doi: 10.1248/bpb.28.1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di-Matteo V., Exposito E. Biochemical and therapeutic effects of antioxidants in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Curr. Drug Target CNS Neurol. Disord. 2003;2:95–107. doi: 10.2174/1568007033482959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duh P.D., Yen G.C., Yen W.J., Chang L.W. Antioxidant effects of water extracts from barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) prepared under different roasting temperatures. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001;49:1455–1463. doi: 10.1021/jf000882l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAOSTATFAO. Statistical database. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Codex Alimentarius Commision: Tunis, Tunesia. http://www.fao.org.

- Faria A., Calhau C., de Freitas V., Mateus N. Procyanidins as antioxidants and tumor cell growth modulators. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006;54(6):2392–2397. doi: 10.1021/jf0526487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faria A., Monteiro R., Mateus N., Azevedo I., Calhau C. Effect of pomegranate (Punica granatum) juice intake on hepatic oxidative stress. Eur. J. Nutr. 2007;46:271–278. doi: 10.1007/s00394-007-0661-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzani G., Papeti A., Massolini G., Daglia M. Anti- and pro-oxidant activity of water soluble components of some common diet vegetables and the effect of thermal treatment. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1998;46:4118–4122. [Google Scholar]

- Gerber M., Boutron-Ruault M.C., Hercberg S., Riboli E., Scalbelt A., Siess M.H. Food and cancer: state of the art about the protective effect of fruits and vegetables. Bull. Cancer. 2002;89:293–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni A.P., Aradhya S.M., Divakar S. Isolation and identification of radical scavenging antioxidant – punicalagin from the pith and capillary membrane of pomegranate fruit. Food Chem. 2004;87:551–557. [Google Scholar]

- Lansky E.P., Newman R.A. Punica granatum (pomegranate) and its potential for prevention and treatment of inflammation and cancer. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007;109:177–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer A.S., Donovan J.L., Pearson D.A. Fruit hydroxycinnamic acids inhibit human low-density lipoprotein oxidation in vitro. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1998;46:1783–1787. [Google Scholar]

- Negi P., Jayaprakasha J. Antioxidant and antibacterial activities of Punica granatum peel extracts. J. Food Sci. 2003;68(4):1473–1477. [Google Scholar]

- Oyaizu M. Studies on product of browning reaction prepared from glucose amine. Jpn. J. Nutr. 1986;44:307–315. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy M., Gupta S., Jacob M., Khan S., Ferreira D. Antioxidant, antimalarial and antimicrobial activities of tannin-rich fractions, ellagi tannins and phenolic acids from Punica granatum L. Planta Med. 2007;73(5):461–467. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-967167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronald Hites, A., 1997. Gas Chromatography Mass Spectroscopy: Handbook of Instrumental Techniques for Analytical Chemistry. pp. 609–611.

- Singleton V.L., Rossi J.A. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic–phosphotungstic acid reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1965;16:144–158. [Google Scholar]

- Vinson J.A., Dabbag Y.A., Serry M.M., Jang J. Plant flavonoids, especially tea flavonols, are powerful antioxidants using an vitro oxidation model for heart disease. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1995;43:2800–2802. [Google Scholar]

- WHO, World Health Organization, available from URL http://www.who.int/medicines/areas/traditional/definitions/en/.

- Yoshikazu S., Hiroko M., Tsutomu N., Inatomi Yuka, Kazuhito W., Munekazu I., Toshiyuki T., Murata, Frank A.L. Inhibitory effect of plant extracts on production of verotoxin by enterohemorrhagic escherichia coli O157: H7. J. Health Sci. 2001;47(5):473. [Google Scholar]