Abstract

SIGNIFICANCE:

Measured corneal biomechanical properties are driven by intraocular pressure, tissue thickness, and inherent material properties. We demonstrate tissue thickness as an important factor in the measurement of corneal biomechanics that can confound short-term effects due to UV riboflavin cross-linking (CXL) treatment.

PURPOSE:

We isolate the effects of tissue thickness on the measured corneal biomechanical properties using optical coherence elastography by experimentally altering the tissue hydration state and stiffness.

METHODS:

Dynamic optical coherence elastography was performed using phase-sensitive optical coherence tomography imaging to quantify the tissue deformation dynamics resulting from a spatially discrete, low-force air pulse (150-μm spot size; 0.8-millisecond duration; <10 Pa [<0.08 mmHg]). The time-dependent surface deformation is characterized by a viscoelastic tissue recovery response, quantified by an exponential decay constant—relaxation rate. Ex vivo rabbit globes (n = 10) with fixed intraocular pressure (15 mmHg) were topically instilled every 5 minutes with 0.9% saline for 60 minutes and 20% dextran for another 60 minutes. Measurements were made after every 20 minutes to determine the central corneal thickness (CCT) and the relaxation rates. Cross-linking treatment was performed on another 13 eyes, applying isotonic riboflavin (n = 6) and hyper-tonic riboflavin (n = 7) every 5 minutes for 30 minutes, followed by UV irradiation (365 nm, 3 mW/cm2) for 30 minutes while instilling riboflavin. Central corneal thickness and relaxation rates were obtained before and after CXL treatment.

RESULTS:

Corneal thickness was positively correlated (R2 = 0.9) with relaxation rates. In the CXL-treated eyes, iso-tonic riboflavin did not affect CCT and showed a significant increase in relaxation rates (+10%; P = .01) from2.29 ms−1 to 2.53 ms−1. Hypertonic riboflavin showed a significant CCT decrease (−31%; P = .01) from 618 μm to 429 μm but showed little change in relaxation rates after CXL treatment.

CONCLUSIONS:

Corneal thickness and stiffness are correlated positively. A higher relaxation rate implied stiffer material properties after isotonic CXL treatment. Hypertonic CXL treatment results in a stiffness decrease that offsets the stiffness increase with CXL treatment.

Graphical Abstract

Current techniques to derive corneal biomechanical properties, for example, optical coherence elastography,1,2 ultrasound elastography,3 Brillouin spectroscopy,4 extensiometry,5 inflation testing,6 and so on, are largely performed ex vivo and do not consider the influence of tissue hydration on the measured material properties. However, the measured corneal biomechanical properties are driven together by intraocular pressure, total thickness, and inherent material properties. Here, we isolate the effects of tissue thickness on the measured corneal biomechanical properties using optical coherence elastography by experimentally altering the tissue’s hydration state and stiffness, while maintaining constant intraocular pressure.

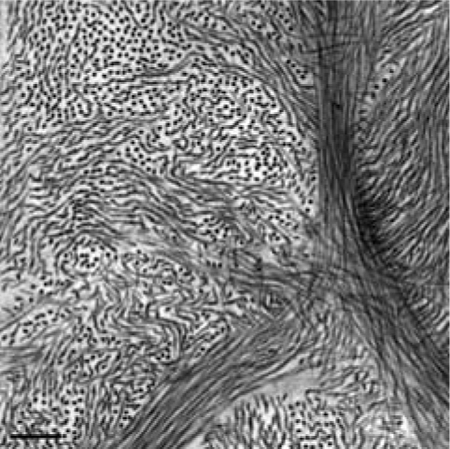

The corneal stroma forms the bulk of the cornea and is ultra-structurally composed of primarily heterotypic collagen fibrils7 (predominantly types I and V) arranged as a pseudohexagonal lattice8 and organized into collagen lamellae with a network of keratocytes interspersed between the lamellae,9 surrounded by ground substance composed mainly of proteoglycans (predominantly dermatan sulfate and keratan sulfate with small amounts of heparin sulfate) with glycosaminoglycan side chains. Epithelial barrier function, stromal imbibition pressure due to the negative charges on proteoglycan-glycosaminoglycan complexes, endothelial pump function, the osmolality of the tears and the aqueous humor, closed-eye (hypoxia) or open-eye, and evaporation due to room environmental conditions (humidity, temperature) are all factors that play a role in influencing in vivo corneal thickness.10–13 However ex vivo, the globe is enucleated; the endothelial pump function slowly declines, while the negative charge on the proteoglycans creates imbibition force driving water into the stroma, altering corneal hydration and generally causing swelling.14

Previous studies show steps taken to preserve or restore physiological corneal thickness prior to the experiments by storing the ocular tissue at 4°C with cotton soaked in 0.9% saline,15 immersing in 20% dextran overnight,16 or using commercial preservative solutions (e.g., Optisol),17 oils,18,19 and so on, to control corneal thickness. However, the effect of these solutions on corneal mechanical properties is not understood. Previous studies show tissue hydration changes affect the measured biomechanical properties. Dias and Ziebarth16 performed atomic force microscopy on ex vivo excised porcine corneas and showed increased Young modulus in swollen corneas immersed in balanced salt solution and 0.9% saline media. A similar increase in hysteresis was shown by Kling and Marcos,20 wherein whole globe inflation testing was performed on ex vivo porcine corneas after treating with Optisol, 8% dextran, 20% dextran, or 0.1% riboflavin dissolved in 20% dextran for 30 minutes. Therefore, the changes in the cor-neal hydration state are known to affect the measured biomechanical properties by influencing the underlying tissue mechanical strength.16,20 Measured corneal stiffness is affected by thickness, which is influenced by tissue hydration, and the elastic modulus. Here, we evaluate the influence of tissue hydration state on the measured corneal biomechanical properties measured by non-contact optical coherence elastography.

In general, 0.1% riboflavin solution dissolved in 20% dextran is used in the UV riboflavin cross-linking treatment performed to slow disease progression by increasing corneal stiffness5,21 for keratoconus22 and post–refractive surgery ectasias.23 However, dextran, which is used in the conventional cross-linking treatment protocol, is a hyperosmotic agent resulting in a tonicity-driven corneal thickness change during treatment.24 Previous histology studies by Hayes et al.25 investigating the short-term effects of UV riboflavin cross-linking treatment question whether the observed changes are due to the treatment alone or due to the hydration state altered by the osmotic effects driven by the presence of dextran. Therefore, the measured corneal material properties after cross-linking are also acutely influenced by corneal hydration. This study evaluates the acute effects of hydration and UV riboflavin cross-linking treatment on measured rabbit corneal biomechanical properties.

Ford and colleagues26 first applied optical coherence elastography methods to the cornea as a nondestructive way to determine corneal biomechanical properties using static mechanical compression as the tissue stimulation method and demonstrated the technique’s capability to resolve submicron displacements in corneal tissue. Recent optical coherence tomography imaging techniques to quantify corneal biomechanical properties include dynamic corneal imaging by indentation,27 air-puff applanation obtained from a modified noncontact tonometer,28,29 and resonant acoustic techniques.30,31 However, the vast majority of investigations have relied on imaging and analyzing the propagation of an elastic wave in the cornea induced by various methods, such as focused micro–air-pulse stimulation,32 acoustic techniques,33 or photothermal excitation.34 The reader is pointed to more comprehensive reviews of optical coherence elastography, which provide additional detail on the progress in the field for corneal applications.1,35,36

In this study, we will implement dynamic optical coherence elastography methods that allow us to nondestructively quantify stiffness in the cornea in an in vivo–like setting wherein an intact cornea without any incisions or excisions is used with a controlled intraocular pressure inside the enucleated globe. We developed a micro–air-pulse stimulator that creates a localized short-duration focal stimulation. This approach is noncontact and provides the capability to obtain spatially localized corneal material properties. Our optical coherence elastography technique involves dynamically loading the tissue using an air pulse to create a focused mechanical stimulation and imaging the induced microscopic tissue motion using phase-sensitive optical coherence tomography to derive the tissue material properties.37–40 The purpose of this study is twofold: (1) develop a way to control and maintain corneal thickness over a period of 200 minutes in controlled environmental conditions in ex vivo rabbit corneas and then apply optical coherence elastography methods to quantify the influence of corneal hydration state on the measured tissue biomechanical properties and (2) evaluate the influence of hydration on the treatment effects due to UV riboflavin cross-linking treatment using optical coherence elastography.

METHODS

Freshly enucleated mature albino whole rabbit eyes (aged >6 months) were obtained from Pel-Freeze Biologicals (Rogers, AR) within 12 hours and were stored in Dulbecco modified eagle medium and used within 36 hours after enucleation.

Altering Tissue Hydration State

Effect of Tonicity on Corneal Thickness

Preliminary experiments with 0.9% saline and 20% dextran solutions showed swelling and shrinkage, respectively. Following that, we instilled five solutions of different osmolalities within that range: 0.9% saline solution (pH 7.4), 2.5% dextran, 5% dextran, 10% dextran, and 20% dextran solutions (all diluted in 0.9% saline) on a total of five groups (each group n = 3 eyes) to obtain the best solution that can maintain corneal thickness in the room’s environmental conditions for 200 minutes. Each cornea was deepithelialized using a blunt spatula. One drop of the solution was applied every 5 minutes for 200 minutes to the de-epithelialized, exposed stromal surface. Central corneal thickness was measured every 5 minutes for 200 minutes in room environmental conditions (temperature ~23°C, relative humidity ~60%). The piecewise comparison from baseline per minute for each group was calculated as the average change in total thickness from baseline over total time. Measured osmolality was obtained for all the solutions using a vapor pressure osmometer (Vapro 5520; Wescor, Inc., Logan, UT). An initial calibration of the osmometer was performed by applying 10 μL of 290 mmol/kg osmolality standard solution (Optimol: OA-029; Wescor, Inc.) onto a solute-free paper disc in the sample holder. Osmolalities of each solution (10 μL) were then measured five times separately and averaged, each time on fresh solute-free paper discs.

Effect of Tissue Thickness on Measured Corneal Biomechanical Properties

Anatomical orientation of the fresh whole rabbit globes (n = 10) was identified; the globes were placed in a holder, and the globes were cannulated at the equator to control the intraocular pressure using two 19-mm gauge needles placed perpendicular to each other to prevent eye globe rotation. One needle was connected to a pressure sensor (Model 41X; Keller Instruments, Newport News, VA) to continuously monitor the intraocular pressure, and the pressure sensor was connected to a computer. The other needle was attached to an automated computer-controlled microinfusion/withdrawal syringe (filled with 0.9% saline solution) pump (NE-500 programmable syringe pump; New Era Pump Systems, Inc., Farmingdale, NY) that adjusted the pressure in a closed feedback loop to maintain the desired intraocular pressure inside the eye globes throughout the experiments. During the optical coherence elastography measurements, the intraocular pressure was set at 15 mmHg. The corneal epithelium was manually debrided using a blunt spatula.

Baseline structural optical coherence tomography imaging of the debrided cornea was performed to obtain the central corneal thickness prior to optical coherence elastography measurements. The baseline central corneal thickness was acquired from a two-dimensional structural image (B-mode) of the rabbit corneal apex comprising 500 A-scans over 6 mm captured by the optical coherence tomography system. The central 50 A-scans over a 0.5-mm lateral displacement across the corneal apex were averaged. The depth-wise image intensity profile showed spiked peaks corresponding to the anterior and posterior corneal surfaces, which were identified manually from the 50 averaged A-scans. The distance between the peaks was measured as the central corneal thickness after correcting for the corneal refractive index (ncornea = 1.376).41

Optical Coherence Elastography Instrument Setup

Optical coherence elastography was performed using a custom-designed phase-stabilized swept source optical coherence tomography imaging system and a micro–air-pulse stimulator that produced focal tissue surface displacements. Fig. 1 shows the schematic of the optical coherence elastography setup. Our previous publications40,42,43 provide a detailed description of the imaging system. Briefly, the imaging system utilizes a swept source laser (HSL2000; Santec, Inc., Torrance, CA) with a central wavelength of 1310 ± 75 nm, A-scan rate of 30 kHz, and an output power of 36 mW. The system has an axial spatial resolution of ~11 μm, lateral spatial resolution of ~16 μm, and high phase stability of ~16 milliradians, corresponding to a displacement sensitivity of ~3 nm in air.43 The home-built air-pulse stimulator gives a focal controlled air pulse with a localized spatiotemporal Gaussian profile having a pressure amplitude ranging from 2 to 10 Pa(0.02 to 0.08 mmHg) delivered over 0.8-millisecond duration through a 150-μm diameter port at an angle of incidence of 45° to the apical surface. The distance between the air-pulse stimulator and the cornea was maintained constant (~200 μm) by manually controlling the z-axis stage.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic of the phase stabilized swept source optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging system (left half), micro–air-pulse stimulator (right top), and intraocular pressure (IOP) control system (right bottom). The OCT imaging beam was coincident with the air pulse stimulator’s port to obtain a colocalized response during ex vivo measurements of rabbit corneal tissue material properties. Intraocular pressure was maintained at 15 mmHg throughout the experiment using a closed-loop microinfusion syringe pump.

Air-pulse stimulation at the corneal apex was used to produce localized mechanical waves, which dispersed internally as an axial compressive force and had tangential lateral propagation (elastic waves). The strain in this study ranged from 0.06 to 3% (4- to 12-μm deformations for a total sample thickness of 400 to 650 μm). This low-amplitude (micrometer-scale) localized tissue displacement was a complex viscoelastic response to the air-pulse stimulation. The optical coherence tomography system was used to record the time-dependent surface response at the corneal apex.42 This measured response is the product of tissue stiffness and thickness where measured stiffness is a measure of elastic (Young) modulus and geometry (thickness in this case), where a faster rebound rate corresponds to a stiffer material.39 For thicker corneas, when the relaxation rate is higher, it takes less time for the corneal surface to recover back to its original position; this shows more resistance to loading and decreased deflection, consistent with greater material stiffness. For thinner corneas, the relaxation rate is lower; this implies the corneal surface recovers back to its original position more slowly and therefore shows less resistance to loading consistent with a less stiff material, hence increased deflection in response to the same deformation force.

The optical coherence tomography system was placed such that the optical coherence tomography imaging axis was coincident with the air pulse stimulator’s port to obtain a colocalized response.39 The phase signal of the tissue response to air-pulse stimulation was captured at the corneal apex in M-mode using the optical coherence tomography. The phase profile of the recorded-localized point response was made up of an initial negative deformation to maximal displacement of the corneal surface, followed by a time-dependent corneal surface recovery back to its original position. This phase profile was unwrapped in time and converted from phase to displacement using the following equation:

| (1) |

where d is the displacement (μm), λ is the central wavelength of the optical coherence tomography system (μm), n is refractive index (nair = 1), and φ is phase (radians) (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2.

Optical coherence elastography of a rabbit eye shows the cor-neal surface displacement (A) as measured by the displacement change from the point response during dynamic corneal surface stimulation and an exponential fit to the observed tissue deformation recovery response. A typical displacement signal recorded at the corneal apex demonstrates an initial negative surface deformation response to the air-pulse force, peak deformation amplitude, and a prolonged viscoelastic recovery response. The relaxation rate (b) is obtained from an exponential fit, starting at the point of maximum deformation amplitude until the end of the observed phase response (~10 milliseconds). Interference spectrums are recorded and transformed via Fourier transform from the wavenumber domain to the distance (depth) domain. Structural image (B) is formed from the real component (intensity) of the transformed signal. The y axis is the depth position in pixels, which can be converted to microns. The phase image (C) is generated by analyzing the complex component of the transformed signal. The y axis of the phase image is the depth position. The gray scale in this image represents the log plot of the intensity or reflectivity, and brighter pixels show the sample’s structural boundaries. Phase is represented by color and ranges ± Pi (2 Pi total). The phase signal was expanded over the 2-Pi limit in postacquisition data processing. The x axis represents time, for this A-scan of a single position over time, in this case, during a deformation stimulus. The conversion factor for pixels to microns in the depth plane: 1 pixel = 3.3 μm; for time (x axis): 1 pixel = 15 microseconds.

The rate at which the corneal anterior surface recovered back to its initial position from the point of maximum displacement captured the complex viscoelastic behavior displayed by the cornea in response to mechanical stimulation. The exponential decay function was calculated by fitting an exponential function to quantify the tissue rebound rate using39

| (2) |

where a is amplitude (μm), and b is decay constant (ms−1) starting at the point of maximum displacement amplitude until the surface recovers back to its original position. The primary outcome measure was the exponential decay constant (b) quantifying the tissue rebound rate termed relaxation rate. Relaxation rate represents the rate at which the air-pulse perturbed corneal surface rebounds from the position of maximal displacement back to its original position.

Following the baseline optical coherence elastography measurements, a hypotonic solution (0.9% saline) was instilled on the corneal surface every 5 minutes for 60 minutes to induce corneal swelling, and then a hypertonic solution (20% dextran solution diluted in 0.9% saline) was instilled every 5 minutes for another 60 minutes to induce corneal thinning. Structural images and point responses were captured every 20 minutes for 120 minutes at a fixed intraocular pressure of 15 mmHg. At each time point, central corneal thickness was determined from structural optical coherence tomography images, and relaxation rates were determined from the optical coherence elastography–recorded viscoelastic recovery responses.

The relationship between the corneal thickness and the relaxation rates were assessed by calculating the correlation coefficient while instilling 0.9% saline and 20% dextran over a period of 120 minutes in rabbit corneas. Two-tailed paired t tests were conducted to assess the change in corneal thickness and relaxation rates before and after instilling 0.9% saline and 20% dextran.

Effect of Isotonic Cross-linking on Measured Corneal Biomechanical Properties

Ex vivo rabbit globes (n = 6) were prepared as described above. After epithelial debridement, baseline structural optical coherence tomography and dynamic optical coherence elastography measurements were obtained with fixed intraocular pressure (15 mmHg). The UV riboflavin cross-linking treatment was performed by instilling isotonic riboflavin solution (0.1% riboflavin dissolved in2.5% dextran) every 5 minutes for 30 minutes on the exposed stromal surface, followed by UV irradiation (365 nm, 3 mW/cm2) for 30 minutes while instilling riboflavin solution. Structural and point responses were measured again posttreatment.

Effect of Hypertonic Cross-linking on Measured Corneal Biomechanical Properties

Ex vivo rabbit globes (n = 7) were prepared and treated as described previously. However, instead of isotonic riboflavin solution, hypertonic riboflavin solution (0.1% riboflavin in 20% dextran [T500] dissolved in 0.9% saline; Dresden protocol)21 was used for the UV riboflavin cross-linking treatment. Central corneal thickness was determined from structural optical coherence tomography imaging, and relaxation rates were determined from the optical coherence elastography–recorded viscoelastic recovery responses before and after UV riboflavin cross-linking treatment. Two-tailed paired t tests were performed to compare the corneal thickness and relaxation rates before and after UV riboflavin cross-linking treatment.

RESULTS

Altering Tissue Hydration State

Effect of Tonicity on Corneal Thickness

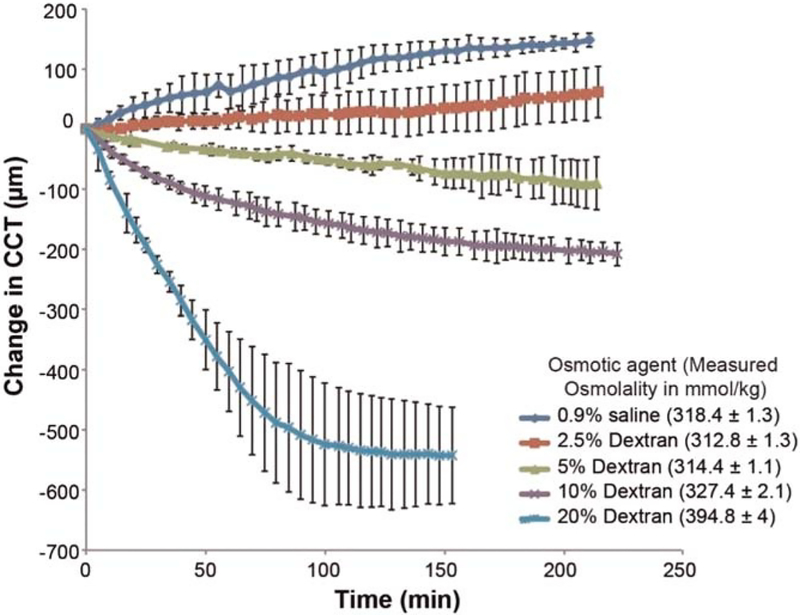

The baseline mean central corneal thickness measured by optical coherence tomography imaging was 749 ± 108 μm (n = 15 eyes, 3 eyes in each group). Fig. 3 shows the central corneal thickness change in ex vivo rabbit eyes with the application of different osmolality solutions over a period of 200 minutes along with their measured osmolality applied on de-epithelialized corneas. Corneal swelling was observed with the application of 0.9% saline and2.5% dextran, whereas corneal deswelling was seen with 5% dextran, 10% dextran, and 20% dextran. Piecewise comparisons from baseline thickness per minute for each group were 0.9% saline: +0.70 ± 0.06 μm/min, 2.5% dextran: +0.29 ± 0.20 μm/min, 5% dextran: −0.42 ± 0.20 μm/min, 10% dextran: −0.94 ± 0.08 μm/min, and 20% dextran: −3.54 ± 0.60 μm/min. Piecewise comparison from baseline thickness per minute showed minimal change in thickness per minute with 2.5% dextran application and maximal thickness change with 20% dextran application.

FIGURE 3.

Central corneal thickness (CCT) change in ex vivo rabbit eyes (n = 15) with the application of different osmolality solutions over 200 minutes measured using optical coherence tomography along with their measured osmolality. Error bars indicate intrameasurement SD. Corneal thickness of rabbit corneas is best controlled by 2.5% dextran solution when used ex vivo within 36 hours after enucleation and epithelial debridement.

Effect of Tissue Thickness on Measured Corneal Biomechanical Properties

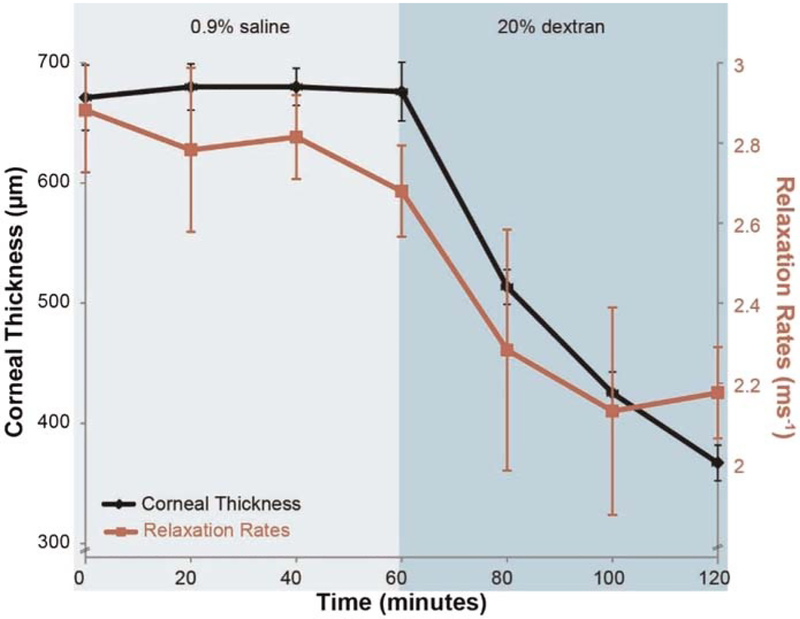

The baseline mean central corneal thickness of the rabbit corneas measured by structural optical coherence tomography imaging was 671 ± 54 μm (n = 10 eyes) at 15 mmHg, and the baseline mean relaxation rate measured by optical coherence elastography imaging was 2.88 ± 0.31 ms−1. Fig. 4 shows the relationship between relaxation rates and corneal thickness in a typical sample obtained using optical coherence elastography while instilling0.9% saline and 20% dextran over a period of 120 minutes in rabbit corneas. After 60 minutes of instilling phosphate-buffered saline on the stromal surface, no significant change was noted in central corneal thickness (−1%; mean difference, −5 μm; 95% confidence interval, −35 to +25 μm; P = .7) and relaxation rates (−6%; −0.18 ms−1; 95% confidence interval, −0.03 to −0.4 ms−1; P = .08). After treatment with 20% dextran for the next 60 minutes, a significant decrease in central corneal thickness (−44%; −303 μm; 95% confidence interval, −269 to −336 μm; P = .01) and relaxation rate (−21%; −0.57 ms−1; 95% confidence interval, −0.37 to −0.76 ms−1; P = .01) was observed. A significant positive correlation (R2 = 0.91; P = .01) was observed between corneal thickness and relaxation rates. There was a decrease in relaxation rates, which is consistent with decreased stiffness, along with a decrease in corneal thickness.

FIGURE 4.

Optical coherence elastography measurements of average corneal thickness and relaxation rates over 120 minutes while instilling 0.9% saline and 20% dextran solutions on de-epithelialized ex vivo rabbit corneas (n = 10). Error bars in the figure represent intrameasurement SD. No significant change (P > .05) in corneal thickness or relaxation rates is noted with 0.9% saline in the first 60 minutes across all samples, whereas instilling 20% dextran caused a significant decrease in corneal thickness (−44%; P = .01) and relaxation rates (−21%; P = .01). A positive correlation (R2 = 0.91; P = .01) is observed between corneal thickness and relaxation rates. There is a decrease in relaxation rates indicating reduced corneal stiffness, with a decrease in corneal thickness.

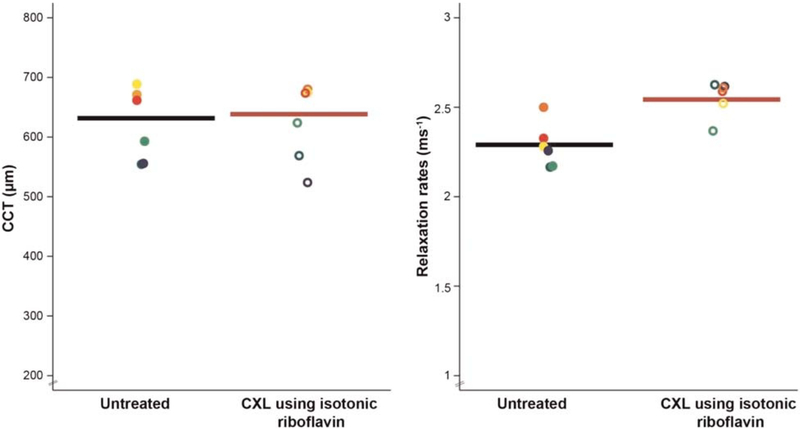

Effect of Isotonic Cross-linking on Measured Corneal Biomechanical Properties

The baseline mean central corneal thickness of the rabbit corneas measured by structural optical coherence tomography imaging was 624 ± 62 μm (n = 6 eyes) at 15 mmHg, and the baseline mean relaxation rates measured by optical coherence elastography imaging was 2.29 ± 0.13 ms−1. Isotonic riboflavin(0.1% riboflavin dissolved in 2.5% dextran) did not affect central corneal thickness (−1%; −5 μm; 95% confidence interval, −21 to +32 μm; P = .62), but showed significantly greater relaxation rates (+10%; +0.24 ms−1; 95% confidence interval, +0.08 to +0.4 ms−1; P = .01) after cross-linking treatment(2.53 ± 0.1 ms−1) after 60 minutes (Fig. 5).

FIGURE 5.

Optical coherence elastography measurements of central corneal thickness (CCT) and relaxation rates measured ex vivo in rabbit eyes (n = 6) before and after UV riboflavin cross-linking (CXL) treatment using isotonic riboflavin solution. Each color denotes the measurement from the same eye before and after treatment (paired analysis). Isotonic riboflavin (0.1% riboflavin dissolved in 2.5% dextran dissolved in 0.9% saline) did not affect CCT (−1%; mean difference, −5 μm; 95% confidence interval [CI], −21 to +32 μm; P = .62) but showed significantly greater relaxation rates (+10%; +0.24 ms−1; 95% CI, +0.08 to +0.4 ms−1; P = .01) after cross-linking treatment, indicating stiffer tissue biomechanical properties posttreatment.

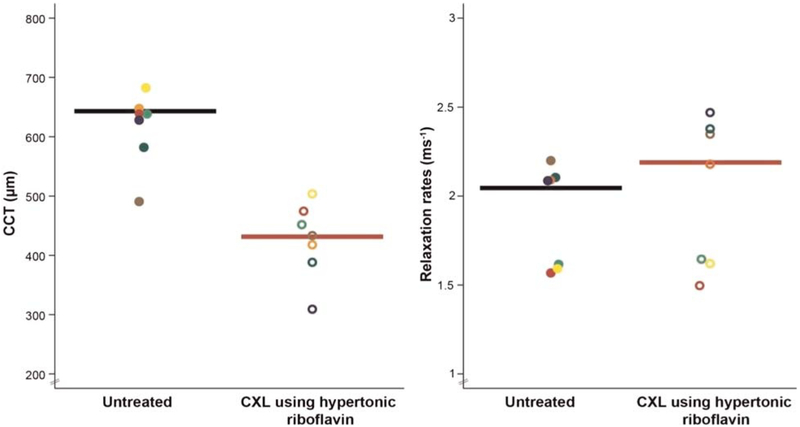

Effect of Hypertonic Cross-linking on Measured Corneal Biomechanical Properties

The baseline mean central corneal thickness of the rabbit corneas measured by structural optical coherence tomography imaging was 618 ± 57 μm (n = 7 eyes) at 15 mmHg, and the baseline mean relaxation rate measured by optical coherence elastography imaging was 1.91 ± 0.29 ms−1. Hypertonic riboflavin (0.1% riboflavin dissolved in 20% dextran) caused a significant central cor-neal thickness decrease (−31%; −189 μμm; 95% confidence interval, −127 to −252 μm; P = .01) after cross-linking treatment (429 ± 62 μm). UV riboflavin cross-linking treatment using hypertonic riboflavin showed no significant change in relaxation rates (+6%; +0.11 ms−1; 95% confidence interval, +0.04 to +0.27 ms−1; P = .12) (Fig. 6).

FIGURE 6.

Optical coherence elastography (OCE) measurements of central corneal thickness (CCT) and relaxation rates (RRs) measured in ex vivo rabbit eyes before and after UV riboflavin cross-linking (CXL) treatment using hypertonic riboflavin solution. Each color denotes the measurement from the same eye before and after treatment (paired analysis). Hypertonic riboflavin (0.1% riboflavin in 20% dextran dissolved in 0.9% saline) caused a significant tonicity-driven CCT decrease (n = 7; −31%; mean difference, −189 μm; 95% confidence interval [CI], −127 to −252; P = .01), causing a corresponding corneal stiffness decrease (Fig. 4) that offset the expected stiffer material properties due to CXL treatment, resulting in no net change in corneal material properties by OCE (RR, +6%; +0.11 ms−1; 95% CI, +0.04 to +0.2; P = .12) after CXL treatment using hypertonic riboflavin.

DISCUSSION

Although several techniques exist to determine corneal biomechanical properties, most require contact, and all but a few techniques are limited to ex vivo use. The Ocular Response Analyzer44 (Reichert Technologies, Depew, NY) and the Corneal Visualization Scheimpflug Technology (CorVis ST; OCULUS, Inc., Arlington, WA)45 are current in vivo devices that utilize air-puff stimulation to derive corneal material properties. However, they create global cor-neal deformation by utilizing an air puff of high volume, large amplitude, and long duration (8 and 35 milliseconds, respectively). To address the issues of contact and global characterization of corneal material properties with the existing techniques, we built a custom micro–air-pulse stimulator that dynamically perturbs the cornea at a focal location noninvasively for a short period (<1 millisecond) and combined it with a phase-sensitive optical coherence elastography.40 Previously, we have evaluated the effect of intraocular pressure on the measured corneal biomechanical properties using air-pulse optical coherence elastography methods and showed a linear increase in corneal stiffness with an increase in intraocular pressure.46,47 In this study, we evaluated the effect of tissue thickness on the measured corneal biomechanical properties using dynamic optical coherence elastography.

After the globe is enucleated and the cornea is de-epithelialized in ex vivo conditions, the endothelial pumps slowly cease to function. The best way to control and maintain ex vivo corneal thickness is to alter stromal tonicity dynamics in controlled environmental conditions. Our results show that 0.9% saline and 2.5% dextran solutions were hypotonic to the corneal stroma, whereas the other solutions (5% dextran, 10% dextran, and 20% dextran solutions) were hypertonic for 200 minutes in de-epithelialized ex vivo corneas under controlled room environmental conditions, where temperature is ~23°C, and relative humidity is ~60%, and used within 36 hours after enucleation. In this study, a solution with osmolality between 312.8 (2.5% dextran) and 314.4 mmol/kg (5% dextran) would be isotonic to the corneal stroma, and 2.5% dextran solution best controlled and maintained ex vivo corneal thickness for more than 200 minutes in controlled environmental conditions. The osmolality of 2.5% dextran solution (312.8 mmol/kg) obtained in this study is higher in comparison with Brubaker and Kupfer’s48 stromal osmolality (304 mOsm ~ mmol/kg) measured from the interstitial fluid (extracellular matrix) in living rabbit corneal stroma. The difference in the osmolality measures could be attributed to the method used to measure the osmolalities, wherein Brubaker and Kupfer48 used the freezing point depression method, whereas we used the vapor pressure depression method (built into the Wescor vapor osmometer). Stahl and colleagues49 suggest the freezing point depression method is not suitable for measuring viscous solutions and can result in a significant change from the actual value.

We used tonicity to quantify the influence of hydration on corneal biomechanical properties using optical coherence elastography. We applied 0.9% saline (hypotonic solution) and showed swollen corneas are stiffer. Application of 20% dextran (hypertonic solution) showed a decrease in relaxation rate, indicating reduced stiffness (−21%), with the decrease in corneal thickness (−44%).50 The changes in corneal stiffness could be a result of two factors: changes in the thickness and changes in the elastic modulus of the cornea. These results are consistent with previous studies. Dias and Ziebarth16 immersed ex vivo porcine corneas with intact sclera rims in balanced salt solution and 0.9% saline medium and showed 115% and 212% increase in Young modulus, respectively, which correlated with 76% and 82% increase in cor-neal thickness driven by the tonicity of the solutions, using atomic force microscopy. Kling and Marcos20 performed whole globe inflation testing on ex vivo porcine corneas after treating with Optisol, 8% dextran, 20% dextran, and 0.1% riboflavin dissolved in 20% dextran for 30 minutes and showed that the cornea became less stiff (higher hysteresis) with decreases in corneal thickness (−57%) using any of the dextran solutions, whereas corneas treated with Optisol showed no significant change in thickness or stiffness.

The increase in stiffness of swollen thick corneas may be due the accumulation of fluid in the stromal extra cellular matrix. In ex vivo corneas, reduced endothelial pump function creates an imbalance in the pump-leak mechanism, resulting in corneal swelling with slow fluid accumulation in the stroma. Driven by the negative swelling pressure of the glycosaminoglycans in the stromal extracellular matrix, the cornea swells and saturates to a greater steady-state thickness as compared with physiologically normal values (from ~400 μm in vivo51 to 600 to 750 μm in ex vivo conditions). We hypothesize that there is an increased amount of tension acting on the cornea surface when excess fluid accumulates within the corneal stroma, resulting in increased stiffness. Following the instillation of a hypertonic agent (20% dextran solution), the excess fluid leaves the corneal tissue, and the cornea is no longer swollen, which decreased the stiffness.

However, these results are limited only to intact ex vivo corneas wherein the corneal endothelial pump function was not optimum and the epithelium was also debrided. We applied 0.9% saline (hypotonic solution) to induce corneal swelling; however, the starting thickness of each ex vivo cornea individually can influence the way it is impacted by the osmotic agents. If the cornea was thin to begin with, applying a hypotonic solution, such as 0.9% saline, will cause further swelling as observed in Fig. 3; however, if the starting corneal thickness was already relatively high, it might not swell as much and remain stable, as observed in Fig. 4. This could be the reason for the difference in results with 0.9% saline application in Fig. 3 and Fig. 4 in the first 60 minutes. Further in vivo studies are needed to better understand the influence of hydration on corneal stiffness in physiologically normal ranges.

Following UV riboflavin cross-linking treatment using isotonic riboflavin solution (riboflavin dissolved in 2.5% dextran solution), the higher relaxation rate implies increased stiffness (10%) as measured by optical coherence elastography. We previously showed significant increase in corneal stiffness after UV riboflavin cross-linking by imaging and subsequently analyzing elastic wave propagation in rabbit corneas after cross-linking treatments using optical coherence elastography.38,52 Ford et al.53 performed optical coherence elastography using mechanical stimulation (gonioscope lens) on human donor eyes and found increased resistance to deformation due to increased corneal stiffness after UV riboflavin cross-linking treatment without dextran.

However, UV riboflavin cross-linking treatment using hypertonic riboflavin (riboflavin dissolved in 20% dextran) showed a tonicity driven corneal thinning with hypertonic riboflavin, resulting in a stiffness decrease that offset the expected stiffer material properties due to UV riboflavin cross-linking treatment, resulting in little change in corneal stiffness after hypertonic UV riboflavin cross-linking treatment. The magnitude of the effect of hydration on cor-neal stiffness was approximately equal and opposite to that of the UV riboflavin cross-linking treatment. Thus, hydration needs to be accounted for during corneal cross-linking.

Dorronsoro et al.29 utilized air-puff stimulation for dynamic optical coherence elastography and showed reduced deformation amplitudes, reduced displaced volumes, and reduced deformation speeds, all of which are consistent with increased corneal stiffness after UV riboflavin cross-linking treatment using riboflavin dissolved in 20% dextran. Nguyen and colleagues3 performed supersonic shear wave imaging and showed a 56% increase in shear wave speed in porcine corneas after cross-linking treatment using riboflavin in 20% dextran. Previous studies using other biomechanical testing techniques have also shown stiffer corneal properties with cross-linking treatment. Wollensak and Iomdina54 performed strip extensiometry on rabbit corneas and showed an increase (78 to 87%) in Young modulus after UV riboflavin cross-linking treatment using riboflavin with 20% dextran. Kling et al.6 conducted inflation testing on porcine corneas and showed an increase (37%) in Young modulus after treatment using riboflavin dissolved in 20% dextran. Brillouin spectroscopy implemented by Scarcelli et al.4 on porcine corneas showed a 39% increase in the Brillouin shift after standard cross-linking procedure. Although all of these studies used hypertonic riboflavin, they still reported an increase in stiffness. Variability in the stiffness increases observed in these studies can be a function of the different regimens and type of mechanical testing performed and the different measured mechanical properties. However, the important point to be noted is that these studies have not evaluated the thickness decrease after treatment and taken into account the influence of thickness on the measured biomechanical properties. The effects of stiffening would be considerably greater in all these studies, if the decrease due to tissue thinning had been accounted for. This demonstrates corneal hydration is an important factor in the measurement of corneal biomechanics that can confound short-term effects due to UV riboflavin cross-linking treatment.

All the results observed in this study were acute changes limited to intact ex vivo corneas. Neither the long-term changes nor the effects of wound healing were accounted for in these experiments. These are important limitations of ex vivo studies that can also be confounded by other variables, for example, the effect of hydration, condition of the tissue (health at the time of death, time of death/excision time, storage conditions, preservation techniques, etc.), boundary conditions, and the method of testing. All these issues can be addressed by measuring corneal biomechanical properties in vivo.

To conclude, this study demonstrates the influence of tissue thickness in the measurement of the corneal biomechanical properties by altering hydration and cross-linking treatments individually and together. Corneal thickness and stiffness are positively correlated. The UV riboflavin cross-linking treatment induces an increase in stiffness; application of hypertonic riboflavin during the UV riboflavin cross-linking treatment results in a decrease in stiffness that offsets the stiffness increase due to the UV riboflavin cross-linking treatment. This is a short-term effect due to the altered corneal hydration. The measured changes in corneal stiffness are the combined effects of thickness, hydration, and Young modulus of the tissue. Because we cannot say for sure what influence hydration may have on Young modulus, we cannot fully distinguish the individual effects of thickness, hydration, and Young modulus on measured corneal stiffness.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: NIH/NEI R01-EY022362 (to KVL) and National Eye Institute P30 EY07551.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: Patent to MDT, KVL, and JL.

REFERENCES

- 1.Larin KV, Sampson DD. Optical Coherence Elastography–OCT at Work in Tissue Biomechanics [Invited]. Biomed Opt Express 2017;8:1172–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmitt J OCT Elastography: Imaging Microscopic Deformation and Strain of Tissue. Opt Express 1998;3: 199–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nguyen TM, Aubry JF, Touboul D, et al. Monitoring of Cornea Elastic Properties Changes during UV-A/Riboflavin-induced Corneal Collagen Cross-linking Using Supersonic Shear Wave Imaging: A Pilot Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2012;53:5948–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scarcelli G, Kling S, Quijano E, et al. Brillouin Microscopy of Collagen Crosslinking: Noncontact Depth-dependent Analysis of Corneal Elastic Modulus. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2013;54:1418–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wollensak G, Spoerl E, Seiler T. Stress-strain Measurements of Human and Porcine Corneas After Riboflavin–Ultraviolet-A–induced Cross-linking. J Cataract Refract Surg 2003;29:1780–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kling S, Remon L, Perez-Escudero A, et al. Corneal Biomechanical Changes After Collagen Cross-linking from Porcine Eye Inflation Experiments. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2010;51:3961–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Michelacci YM. Collagens and Proteoglycans of the Corneal Extracellular Matrix. Braz J Med Biol Res 2003;36:1037–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maurice DM. The Structure and Transparency of the Cornea. J Physiol 1957;136:263–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meek KM, Quantock AJ. The Use of X-ray Scattering Techniques to Determine Corneal Ultrastructure. Prog Retin Eye Res 2001;20:95–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mishima S, Maurice DM. The Effect of Normal Evaporation on the Eye. Exp Eye Res 1961;1:46–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen SR, Polse KA, Brand RJ, et al. Humidity Effects on Corneal Hydration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1990;31:1282–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Metha AB, Crane AM, Rylander HG 3rd, et al. Maintaining the Cornea and the General Physiological Environment in Visual Neurophysiology Experiments. J Neurosci Methods 2001;109:153–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bonanno JA. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying the Corneal Endothelial Pump. Exp Eye Res 2012; 95:2–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bourne WM. Biology of the Corneal Endothelium in Health and Disease. Eye (Lond) 2003;17:912–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bueno JM, Gualda EJ, Giakoumaki A, et al. Multi-photon Microscopy of Ex Vivo Corneas After Collagen Cross-linking. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011;52: 5325–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dias J, Ziebarth NM. Impact of Hydration Media on Ex Vivo Corneal Elasticity Measurements. Eye Contact Lens 2015;41:281–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elsheikh A, Wang D, Brown M, et al. Assessment of Corneal Biomechanical Properties and Their Variation with Age. Curr Eye Res 2007;32:11–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nash IS, Greene PR, Foster CS. Comparison of Mechanical Properties of Keratoconus and Normal Corneas. Exp Eye Res 1982;35:413–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Winkler M, Chai D, Kriling S, et al. Nonlinear Optical Macroscopic Assessment of 3-D Corneal Collagen Organization and Axial Biomechanics. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011;52:8818–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kling S, Marcos S. Effect of Hydration State and Storage Media on Corneal Biomechanical Response from in Vitro Inflation Tests. J Refract Surg 2013;29:490–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wollensak G, Spoerl E, Seiler T. Riboflavin/Ultraviolet-A–induced Collagen Crosslinking for the Treatment of Keratoconus. Am J Ophthalmol 2003;135: 620–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hersh PS, Greenstein SA, Fry KL. Corneal Collagen Crosslinking for Keratoconus and Corneal Ectasia: One-year Results. J Cataract Refract Surg 2011;37: 149–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hafezi F, Kanellopoulos J, Wiltfang R, et al. Corneal Collagen Crosslinking with Riboflavin and Ultraviolet a to Treat Induced Keratectasia After Laser in Situ Keratomileusis. J Cataract Refract Surg 2007;33: 2035–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kling S, Marcos S. Contributing Factors to Corneal Deformation in Air Puff Measurements. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2013;54:5078–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayes S, Boote C, Kamma-Lorger CS, et al. Riboflavin/UVA Collagen Cross-linking–induced Changes in Normal and Keratoconus Corneal Stroma. PLoS One 2011;6:e22405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ford MR, Dupps WJ Jr., Rollins AM, et al. Method for Optical Coherence Elastography of the Cornea. J Biomed Opt 2011;16:016005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grabner G, Eilmsteiner R, Steindl C, et al. Dynamic Corneal Imaging. J Cataract Refract Surg 2005;31: 163–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alonso-Caneiro D, Karnowski K, Kaluzny BJ, et al. Assessment of Corneal Dynamics with High-speed Swept Source Optical Coherence Tomography Combined with an Air Puff System. Opt Express 2011; 19:14188–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dorronsoro C, Pascual D, Perez-Merino P, et al. Dynamic OCT Measurement of Corneal Deformation by an Air Puff in Normal and Cross-linked Corneas. Biomed Opt Express 2012;3:473–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akca BI, Chang EW, Kling S, et al. Observation of Sound-induced Corneal Vibrational Modes by Optical Coherence Tomography. Biomed Opt Express 2015;6: 3313–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qu Y, Ma T, He Y, et al. Acoustic Radiation Force Optical Coherence Elastography of Corneal Tissue. IEEE J Sel Top Quantum Electron 2016;22:6803507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang S, Larin KV. Shear Wave Imaging Optical Coherence Tomography (SWI-OCT) for Ocular Tissue Bio-mechanics. Opt Lett 2014;39:41–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ambrozinski L, Song S, Yoon SJ, et al. Acoustic Micro-tapping for Non-contact 4D Imaging of Tissue Elasticity. Sci Rep 2016;6:38967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li C, Guan G, Huang Z, et al. Noncontact All-optical Measurement of Corneal Elasticity. Opt Lett 2012;37: 1625–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liang X, Crecea V, Boppart SA. Dynamic Optical Coherence Elastography: A Review. J Innov Opt Health Sci 2010;3:221–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang S, Larin KV. Optical Coherence Elastography for Tissue Characterization: A Review. J Biophotonics 2015;8:279–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Twa MD, Li J, Vantipalli S, et al. Spatial Characterization of Corneal Biomechanical Properties with Optical Coherence Elastography after UV Cross-Linking. Biomed Opt Express 2014;5:1419–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li J, Han Z, Singh M, et al. Differentiating Untreated and Cross-linked Porcine Corneas of the Same Measured Stiffness with Optical Coherence Elastography. J Biomed Opt 2014;19:110502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li J, Wang S, Singh M, et al. Air-pulse OCE for Assessment of Age-related Changes in Mouse Cornea in Vivo. Laser Phys Lett 2014;11:065601. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang S, Larin KV, Li J, et al. A Focused Air-pulse System for Optical-Coherence-Tomography–based Measurements of Tissue Elasticity. Laser Phys Lett 2013; 10:075605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mandell RB. Corneal Power Correction Factor for Photorefractive Keratectomy. J Refract Surg 1994;10: 125–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li J, Wang S, Manapuram RK, et al. Dynamic Optical Coherence Tomography Measurements of Elastic Wave Propagation in Tissue-mimicking Phantoms and Mouse Cornea in Vivo. J Biomed Opt 2013; 18:121503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Manapuram RK, Manne VGR, Larin KV. Development of Phase-stabilized Swept-source OCT for the Ultrasensitive Quantification of Microbubbles. Laser Phys Lett 2008;18:1080–6. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kotecha A, Elsheikh A, Roberts CR, et al. Corneal Thickness- and Age-related Biomechanical Properties of the Cornea Measured with the Ocular Response Analyzer. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2006; 47:5337–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kling S, Bekesi N, Dorronsoro C, et al. Corneal Viscoelastic Properties from Finite-element Analysis of in Vivo Air-puff Deformation. PLoS One 2014; 9:e104904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Han Z, Li J, Singh M, et al. Assessing Corneal Visco-elasticity After Crosslinking at Different IOP by Noncon-tact OCE and a Modified Lamb Wave Model. Proc SPIE 2017:1004502–1. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Singh M, Li JS, Han ZL, et al. Investigating Elastic Anisotropy of the Porcine Cornea as a Function of Intraocular Pressure with Optical Coherence Elastography. J Refract Surg 2016;32:562–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brubaker RF, Kupfer C. Microcryoscopic Determination of the Osmolality of Interstitial Fluid in the Living Rabbit Cornea. Invest Ophthalmol 1962;1:653–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stahl U, Willcox M, Stapleton F. Osmolality and Tear Film Dynamics. Clin Exp Optom 2012;95:3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Twa MD, Vantipalli S, Sing M, et al. Influence of Cor-neal Hydration on Optical Coherence Elastography. Proc SPIE 2016;9693. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chan T, Payor S, Holden BA. Corneal Thickness Profiles in Rabbits Using an Ultrasonic Pachometer. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1983;24:1408–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Singh M, Li J, Han Z, et al. Evaluating the Effects of Riboflavin/UV-A and Rose-bengal/Green Light Cross-linking of the Rabbit Cornea by Noncontact Optical Coherence Elastography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2016; 57:October112–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ford MR, Roy AS, Rollins AM, et al. Serial Biomechanical Comparison of Edematous, Normal, and Collagen Crosslinked Human Donor Corneas Using Optical Coherence Elastography. J Cataract Refract Surg 2014;40:1041–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wollensak G, Iomdina E. Long-term Biomechanical Properties of Rabbit Cornea After Photodynamic Collagen Crosslinking. Acta Ophthalmol 2009;87:48–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]