Abstract

The role of cystathionine-γ-lyase (CSE) derived H2S in the hypoxic and anoxic responses of the carotid body (CB) were examined. Experiments were performed on Sprague-Dawley rats, wild type and CSE knockout mice on C57BL/6J background. Hypoxia (pO2=37±3 mmHg) increased the CB sensory nerve activity and elevated H2S levels in rats. In contrast, anoxia (pO2=5±4 mmHg) produced only a modest CB sensory excitation with no change in H2S levels. DL-propargylglycine (DL-PAG), a blocker of CSE, inhibited hypoxia but not anoxia-evoked CB sensory excitation and [Ca2+]i elevation of glomus cells. The inhibitory effects of DL-PAG on hypoxia were seen: a) when it is dissolved in saline but not in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and in glomus cells cultured for18h but not in cells either soon after isolation or after prolonged culturing (72h) requiring 1–3h of incubation. On the other hand, anoxia-induced [Ca2+]i responses of glomus cell were blocked by high concentration of DL-PAG (300μM) either alone or in combination with aminooxyacetic acid (AOAA; 300μM) with a decreased cell viability. Anoxia produced a weak CB sensory excitation and robust [Ca2+]i elevation in glomus cells of both wild-type and CSE null mice. As compared to wild-type, CSE null mice exhibited impaired CB chemo reflex as evidenced by attenuated efferent phrenic nerve responses to brief hyperoxia (Dejours test), and hypoxia. Inhalation of 100% N2 (anoxia) depressed breathing in both CSE null and wild-type mice. These observations demonstrate that a) hypoxia and anoxia are not analogous stimuli for studying CB physiology and b) CSE-derived H2S contributes to CB response to hypoxia but not to that of anoxia.

Keywords: Cystathionine-γ-lyase, H2S synthesis inhibitors, hypoxic ventilatory response, carotid body chemo reflex

1. Introduction

A decrease in partial pressure of O2 in the arterial blood (hypoxemia) is sensed within seconds by carotid bodies (CBs), and the resulting increase in the sensory nerve activity triggers the CB chemo reflex, which is an important regulator of cardio-respiratory functions (Fidone & Gonzalez, 1986; Gonzalez et al., 1994; Kumar & Prabhakar, 2012; López-Barneo et al., 2016).Various theories have been proposed to explain how hypoxemia stimulates the carotid body sensory nerve activity (Kumar & Prabhakar, 2012; Chang, 2017; Leonard et al., 2018). Emerging evidence suggests that gaseous messenger hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is an important mediator of carotid body sensory nerve activation by hypoxia (Li et al., 2010; Peng et al., 2010; Telezhkin et al., 2010; Yuan et al., 2015; Prabhakar et al., 2018). Glomus cells, the primary O2 sensing cells in the CB, express at least two H2S-synthesizing enzymes, cystathionine-γ-lyase (CSE)(Li et al., 2010; Peng et al., 2010) and cystathionine β-synthase (CBS)(Li et al., 2010). Hypoxia (pO2=~40 mmHg) increases H2S generation in the CB and this effect was lost in CSE null mice. Mice lacking CSE exhibit severely impaired hypoxia-evoked CB sensory nerve excitation and stimulation of breathing (Peng et al., 2010). Exogenous H2S, like hypoxia, increases the CB sensory nerve activity of rats, mice, rabbits and cats (Li et al., 2010; Peng et al., 2010; Jiao et al., 2015), and depolarizes glomus cells (Buckler, 2012). Hypoxia-evoked [Ca2+]i elevation and transmitter secretion from glomus cells are impaired in rats treated with H2S synthesis inhibitor and in CSE null mice (Makarenko et al., 2012). CBs of Brown-Norway rat exhibit markedly attenuated sensory nerve excitation by hypoxia and this effect was associated with reduced H2S generation by low O2 as compared with Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats; whereas spontaneous hypertensive rats CBs have greater H2S generation by hypoxia and augmented hypoxic sensitivity as compared to SD rats (Peng et al., 2014).

The above studies suggest a role for H2S in hypoxic sensing by CB. However, this possibility was questioned in recent studies (Kim et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2017). These studies reported glomus cell responses to anoxia were unaffected by H2S synthesis inhibitors (Kim et al., 2015) and unaltered hypoxic ventilatory response (HVR), which is a hallmark of CB chemo reflex in CSE null mice (Wang et al., 2017). Anoxia, unlike hypoxia, is characterized by a complete lack of oxygen. Unlike hypoxia, little information is available on the effects of anoxia on the CB sensory activity and breathing. In the present study, we examined the role of H2S in the carotid body sensory nerve activity, [Ca2+]i responses of glomus cells, and breathing responses to hypoxia and anoxia.

2. Methods

Experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Chicago. All experiments were performed on adult (6–7 weeks old) male Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories), and 6–8 weeks old male wild-type (WT) and CSE null mice (C57BL/6J and 129sv background, gift from Dr. Solomon. H. Snyder and originally developed by Dr. Rui Wang).

2.1. Recording of CB sensory nerve activity

Sensory nerve activity from CB ex vivo was recorded as previously described (Peng et al., 2003). Briefly, CBs along with the sinus nerves were harvested from anaesthetized rats, placed in a recording chamber (volume, 250μl) and superfused with warm physiological saline (35°C) at a rate of 2 ml/ minute. The composition of the medium was (in mM): NaCl (140), KCl (5.4), CaCl2 (2.5), MgCl2 (0.5), HEPES (5.5), glucose (11), sucrose (5), and the solution was bubbled with 100% O2. To facilitate recording of clearly identifiable action potentials, the sinus nerve was treated with 0.1% collagenase for 5 min. Action potentials (2–5 active units) were recorded from one of the nerve bundles with a suction electrode and stored in a computer via an A/D translation board (PowerLab/8P, AD Instruments Pty Ltd, Australia). ‘Single’ units were selected based on the height and duration of the individual action potentials using a spike discrimination program (Spike Histogram Program, AD Instruments). In each CB, at least two chemoreceptor units were analyzed. pO2, pCO2 and pH of the medium were determined by a blood gas analyzer (ABL 80, Radiometer, Copenhagen, Denmark).

2.2. Primary cultures of glomus cells

Primary cultures of glomus cells were prepared as described previously (Makarenko et al., 2012). Briefly, CBs were harvested from urethane (1.2 g/kg, I.P.) anesthetized rats and mice. Glomus cells were dissociated using a mixture of collagenase P (2 mg/ml; Roche, USA), DNase (15μg/ml; Sigma, USA), and bovine serum albumin (BSA; 3 mg/ml; Sigma, USA) at 37°C for 20 min, followed by a 15 min incubation in medium containing DNase (30μg/ml). Cells were plated on collagen (type VII; Sigma)-coated cover slips and maintained at 37°C in a 7% CO2 + 20% O2 incubator for 3 or 18 or 72h. The growth medium consisted of F-12K medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 1% fetal bovine serum, insulin-transferrin-selenium (ITS-X; Invitrogen), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin/glutamine mixture (Invitrogen).

2.3. Measurements of [Ca 2+]i

Glomus cells were incubated in Hanks Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) with 2μM fura-2-AM and 1 mg/ml albumin for 30 min and then washed in a fura-2-free solution for 30 min at 37°C. The cover slip was transferred to an experimental chamber for determining the changes in [Ca2+]i. Background fluorescence at 340nm and 380 nm wavelengths was obtained from an area of the cover slip that was devoid of cells. On each cover slip, up to thirty glomus cells were selected (identified by their characteristic clustering) and individual cells were imaged. Image pairs (one at 340nm and the other at 380nm wavelength, respectively) were obtained every 2 s by averaging 16 frames at each wavelength. Data were continuously collected throughout the experiment. Background fluorescence was subtracted from the cell data obtained at the individual wavelengths. The image obtained at 340 nm was divided by the 380 nm image to obtain ratiometric image. Ratios were converted to free [Ca2+]i using calibration curves constructed in vitro by adding fura-2 (50μM free acid) to solutions containing known concentrations of Ca2+ (0 –2000 nM). The recording chamber was continually superfused with solution from gravity-fed reservoirs.

2.4. Preparation of hypoxia and anoxia medium

For challenging with hypoxia, solutions were degassed for three hours and were bubbled with 100% N2 continuously that resulted in a medium pO2 of 37± 3 mmHg as measured by a blood gas analyzer (ABL 80). Anoxic medium was prepared by adding either 0.5mM of Na2S2O4 (Sodium dithionite) or 2 units/ml of glucose oxidase and 100units/ml of catalase to the medium bubbled with 100% N2 as described (Kim et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2017), which resulted in a medium pO2 of 5±4 mmHg as measured by a blood gas analyzer.

2.5. Measurements of H2S

H2S levels in the glomus cells (isolated from ten rat CBs) or CBs (eight CBs were pooled) were determined as described previously (Peng et al., 2010; Makarenko et al., 2012). Briefly, either glomus cell or CB homogenates were prepared in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). The enzyme reaction was carried out in sealed tubes flushed with either room air or 1% O2-99% N2 gas mixture. The pO2 of the reaction medium was determined by blood gas analyzer (ABL80). The assay mixture in a total volume of 500μl contained (in final concentration) 800μM L-cysteine, 80μM pyridoxal 5′-phosphate, 100mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), and cell homogenate (2μg of protein). The reaction mixture was incubated at 37°C for 1 h and at the end of the reaction, alkaline zinc acetate (1% wt/vol; 250μl) and trichloroacetic acid (10% vol/vol) were added sequentially to trap H2S generated and to stop the reaction, respectively. The zinc sulfide formed was reacted sequentially with acidic N,N-dimethyl-p-phenylenediamine sulfate (20μM) and ferric chloride (30μM) and the absorbance was measured at 670 nm using a micro plate reader. A standard curve relating the concentration of Na2S and absorbance was used to calculate H2S concentration and expressed as nanomoles of H2S formed per hour per milligram protein.

2.6. Cell viability assay

Glomus cells were cultured in six-well plates for 18 h and then treated with either 300μM DL-PAG or a mixture of 300μM DL-PAG and 300μM AOAA for 3 hours followed by mixing cell suspension with 0.4% trypan blue solution in 9:1 ratio. After three minutes of incubation, the counting plate containing the live cells and dead cells were counted. Cell viability was measured using the following formula: living cell rate (%) = living cell / (number of living cells + dead cells) ×100.

2.7. Measurements of efferent phrenic nerve activity

Mice were anaesthetized with intraperitoneal injections of urethane (1.2g/kg). Supplemental doses (10% of the initial dose of anesthetic) were given when corneal reflexes or responses to toe pinch were observed. Animals were placed on a warm surgical board and a tracheotomy was performed through a middle neck skin incision. The trachea was cannulated and mice were allowed to breathe spontaneously. Core body temperature was monitored by a rectal thermistor probe and maintained at 37±1°C by a heating pad. The phrenic nerve was isolated unilaterally at the level of the C3 and C4 spinal segments, cut distally, and placed on bipolar stainless steel electrodes. Integrated efferent phrenic nerve activity was monitored as an index of central respiratory neuronal output. The electrical activity was filtered (band pass 0.3– 1.0 kHz), amplified, and passed through Paynter filters (time constant of 100 ms; CWE Inc.) to obtain a moving average signal. Data were stored in the computer for further analysis. At the end of the experiment, mice were killed by overdose of urethane (>3.6 g/kg). The effects of brief hyperoxic challenge on respiration(DEJOURS, 1962) were examined. Baseline phrenic nerve activity was recorded for 5 min, while the mice breathed room air. 100 % O2 was added to the inspired air for 30 seconds. Oxygen was administered through a needle placed in the tracheal cannula and gas flow was controlled by a flow meter. Respiration (respiratory rate and tidal phrenic nerve activity) was analyzed for one minute during breathing room air and the last 15s of 30s of hyperoxia challenge. Breathing during the initial 10s of hyperoxia was excluded for analysis because of the dead space of the tubing. The effects of hypoxia (12% O2 balanced nitrogen) and hypercapnia (10% CO2 balanced 21% O2 and 79% N2) on efferent phrenic nerve activity were also determined. Baseline phrenic nerve activity was monitored while the animals breathed room air. Subsequently, inspired gas was switched to either 12% O2 or 10% CO2 for 3min. The duration of 3min for hypoxia was chosen because longer duration of hypoxic exposure (> 5min) results in lowering of body temperature and respiratory depression in wild type mice (Kline et al., 1998). In another series of experiments, the effects of 100% N2 (anoxia) for 10s on efferent phrenic nerve responses were examined in age matched wild-type and CSE null mice. Extending the duration of 100% N2 inhalation resulted in irreversible respiratory depression followed by death of mice.

2.8. Drugs and Chemicals

All stock solutions were made fresh before the experiments. Aminooxyacetic acid (AOAA), Catalase, Sodium dithionite, DL-propargylglycine (DL-PAG), Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and Glucose Oxidase were obtained from commercial sources (Sigma Aldrich). Stock solutions were made in saline and pH of final solutions was adjusted to ~7.4. Stock solutions were prepared fresh and stored on ice before use unless otherwise specified. Desired concentrations of drugs were added to culture plates containing glomus cells.

2.9. Analysis of data

CB sensory nerve activity (discharge from ‘single’ units) was averaged during 3 min of baseline and during the 3min of gas challenge and expressed as impulses/second unless otherwise stated The following respiratory variables were analyzed in anesthetized mice: respiratory rate (RR, number of phrenic bursts/min), amplitude of the integrated tidal phrenic nerve activity (a.u., arbitrary units) and minute neural respiration (arbitrary units /min; RR × amplitude of the integrated phrenic nerve activity). Average data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was assessed by Student’s t-test for statistical comparisons between two groups and one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test for multiple groups’ comparison. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Role of H2S in the rat carotid body sensory nerve responses to hypoxia and anoxia

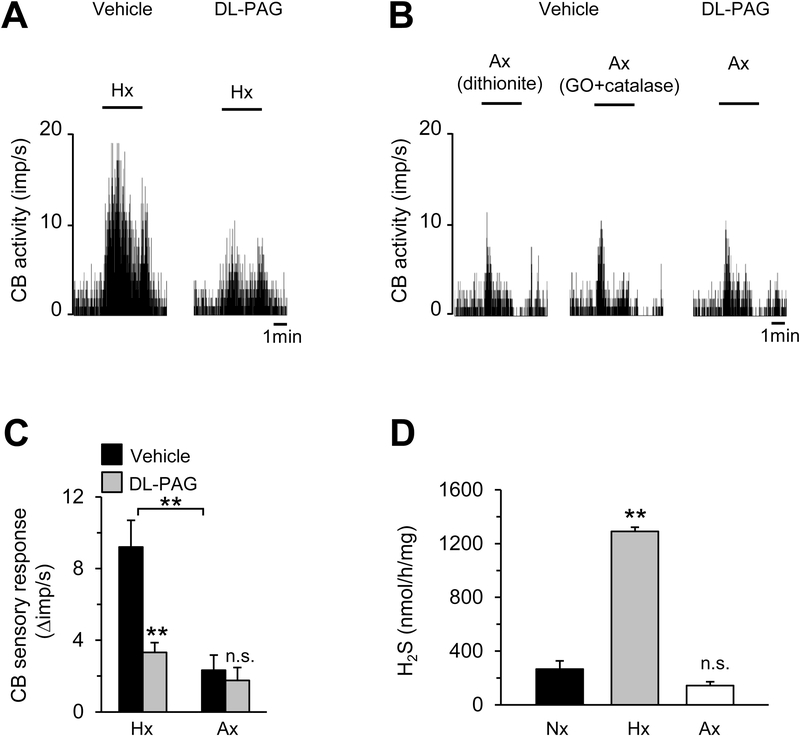

Sensory nerve activity was recorded from ex vivo rat CBs to exclude confounding influence from cardiovascular changes in intact animals. Hypoxia (Hx; pO2 37± 3mmHg) increased CB sensory nerve activity, and this effect was attenuated in rats treated with DL-PAG, an inhibitor CSE (Fig. 1A). Unlike hypoxia, anoxia (Ax) induced either by sodium dithionite or with glucose oxidase combined with catalase (pO2 5±4 mmHg) produced a brief and modest stimulation of the CB sensory nerve activity followed by return to baseline in the continued presence of the stimulus and this effect was unaltered by DL-PAG (Fig. 1B). The magnitude of CB sensory excitation produced by anoxia induced either by sodium dithionite or by glucose oxidase combined with catalase was comparable. Therefore, the data from both approaches were combined for further analysis. Average data showed that DL-PAG inhibited only hypoxia-evoked but not anoxia-induced CB sensory excitation (Fig. 1C). Hypoxia but not anoxia increased H2S levels in the CB as compared to normoxia (Nx) (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1. Effect of DL-PAG on CB sensory nerve response to hypoxia and anoxia.

A & B. Examples of CB sensory activity in response to hypoxia (Hx; pO2 = 37± 3mmHg; A) or anoxia (Ax; pO2 = 5±4 mmHg; B) in rats treated with either vehicle (saline) or DL-PAG (30mg/kg). Anoxia was induced by adding either sodium dithionite (0.5mM), or glucose oxidase (GO; 2 units/ml) combined with catalase (100units/ml) to the N2 equilibrated medium. Horizontal bars represent the duration of the hypoxia (Hx), or anoxia (Ax). C. Average data (mean ± SEM) of CB sensory responses to hypoxia or anoxia in rats treated with vehicle or DL-PAG and presented as stimulus-evoked response minus baseline levels (Δ impulse/sec), n=21 fibers from 10 CBs (vehicle), and 18 fibers from 8 CBs (DL-PAG). D. Average data (mean ± SEM) of H2S levels in the rat CBs treated with normoxia (Nx), hypoxia (Hx) or anoxia (Ax) for five minutes (n= 5 measurements in triplicate for each group).. **, P < 0.01; n.s, not significant (P > 0.05).

3.2. Low concentration of DL-PAG selectively inhibits glomus cell responses to hypoxia

We next assessed whether H2S is required for glomus cell [Ca2+]i responses to hypoxia and anoxia. Studies were conducted on glomus cells isolated from adult rat carotid bodies, and were maintained overnight (~18 hours) in a growth medium. To assess the role of H2S, cells were treated with 50μM DL-PAG for 3h prior to measuring [Ca2+]i. The choice of 50μM DL-PAG was based on our earlier study (Makarenko et al., 2012).

Hypoxia increased [Ca2+]i and this effect was attenuated by DL-PAG (Fig. 2A). Anoxia, induced either by sodium dithionite or by glucose oxidase plus catalase produced a more pronounced [Ca2+]i elevation than hypoxia, but this effect was unaltered by DL-PAG (Fig. 2B). The data from sodium dithionite and glucose oxidase plus catalase were combined for further analysis. Average results showed that 50μM DL-PAG inhibited the [Ca2+]i response of glomus cells to hypoxia, whereas it had no effect on glomus cell response to anoxia (Figs. 2 C-D). [Ca2+]i elevation caused by 40 mM KCl was also unaffected by 50μM of DL-PAG (Figs. 2 E-F).

Figure 2. Low concentration of DL-PAG inhibits [Ca2+]i responses of glomus cells to hypoxia but not to anoxia.

A & B. Examples of [Ca2+]i responses to hypoxia (Hx; pO2 = 37± 3mmHg; A) or anoxia (Ax; pO2 = 5±4 mmHg; B) in rat glomus cells treated with either vehicle or 50μM DL-PAG, n = 9~15 cells for each treatment. C. Average data (mean ± SEM) of hypoxia-induced [Ca2+]i responses of glomus cells treated with either vehicle (n=29–42 cells) or 50 μM DL-PAG (n = 30–54 cells), and presented as stimulus-evoked response minus baseline levels (Δ[Ca2+]i, nM), D. Average data (mean ± SEM) of anoxia-induced [Ca2+]i responses treated with either vehicle (n=53 cells) or 50 μM DL-PAG (n = 40 cells). E. Examples of [Ca2+]iresponses to 40 mM KCl of glomus cells treated with either vehicle (n = 13 cells) or 50 μM DL-PAG (n = 11 cells). F. Average data (mean ± SEM) of KCl-induced [Ca2+]i responses treated with either vehicle (n = 47 cells) or 50 μM DL-PAG (n = 40 cells). Horizontal bars in A, B and E represent the duration of the hypoxic, anoxia or high K+ challenges, respectively. **, P < 0.01; n.s., not significant (P > 0.05).

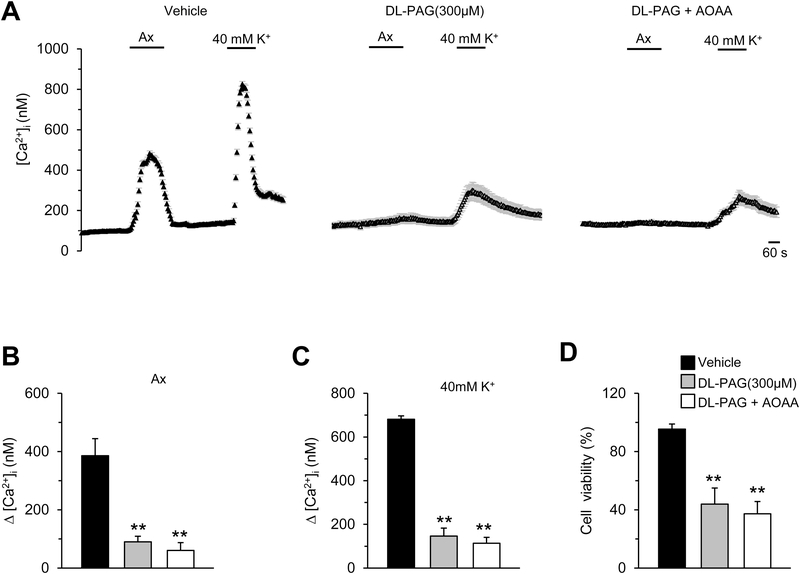

3.3. High concentration of DL-PAG non-selectively inhibits glomus cell response to anoxia

Kim et al., (2015) used 300μM of DL-PAG either alone or in combination with AOAA, another H2S synthesis inhibitor in their study. Therefore, we determined whether higher concentration of DL-PAG alone or in combination with AOAA is required to inhibit glomus cell response to anoxia. DL-PAG at 300μM concentration markedly reduced anoxia-evoked [Ca2+]i elevation (Figs. 3A-B). However, at this high concentration, DL-PAG also reduced [Ca2+]i elevation by 40mM KCl (Figs. 3A-C). Combined application of DL-PAG and AOAA (300μM each) further reduced [Ca2+]i elevation by anoxia and KCl (Figs. 3A-C). DL-PAG either alone or in combination with AOAA (300 μM each) also reduced glomus cell viability by ~60% (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3. High concentration of DL-PAG non-selectively inhibits [Ca2+]i responses of glomus cells to anoxia.

A. Examples of [Ca2+]i responses to anoxia (Ax; pO2 = 5±4 mmHg) or KCl (40mM) in rat glomus cells treated with either vehicle, DL-PAG alone (300 μM), or DL-PAG combined with AOAA (300 μM each), n=10~15 cells for each treatment. B. & C. Average data (mean ± SEM) of [Ca2+]i responses to anoxia (B) or 40 mM KCl (C), and presented as stimulus-evoked response minus baseline levels (Δ[Ca2+]i, nM), n=53~75 cells for each treatment. D. Cell viability of glomus cells treated with vehicle or DL-PAG alone (300μM), or DL-PAG combined with AOAA (300μM each) for 3 hours. Data was presented as mean ± SEM from five experiments in triplicate. **, P < 0.01, compared with responses (B and C) or viability (D) of cells treated with vehicle.

3.4. Experimental conditions influencing the efficacy of DL-PAG

Thus far our results showed that low concentration of DL-PAG (50μM) selectively inhibits [Ca2+]i responses of glomus cell to hypoxia. We then assessed experimental conditions influencing the inhibitory effects of DL-PAG on glomus cell [Ca2+]i response to hypoxia.

3.4.1. Effects of solvents

DL-PAG is a water soluble compound. Accordingly above described studies were performed on DL-PAG dissolved in saline. However, Kim and co-workers studied the effects of DL-PAG dissolved in 0.1% DMSO (Kim et al., 2015)page 33 and legend of Fig. 2). Therefore, we compared the efficacy of DL-PAG dissolved in saline versus DMSO inhibiting H2S levels in the rat CB. DL-PAG dissolved in saline inhibited H2S production in the CB in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 4A). In contrast, DL-PAG dissolved in DMSO modestly inhibited H2S generation (Fig. 4B). Similarly, DL-PAG reduced [Ca2+]i responses to hypoxia when dissolved in saline but not DMSO (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4. Comparison of DL-PAG efficacy dissolved in saline versus DMSO.

Average data (mean ± SEM; n=5 run in triplicate) of the effects of DL-PAG dissolved in saline (A) or DMSO (B) on CB H2S levels. C. Average data (mean ± SEM) of hypoxia (Hx; pO2 = 37± 3mmHg)-evoked [Ca2+]i responses of glomus cells treated with DL-PAG (50μM) dissolved either in saline (n=40 cells) or DMSO (n=37 cells), and presented as stimulus-evoked response minus baseline levels (Δ[Ca2+]i, nM). *, P< 0.05, **, P < 0.01; n.s., not significant (P > 0.05).

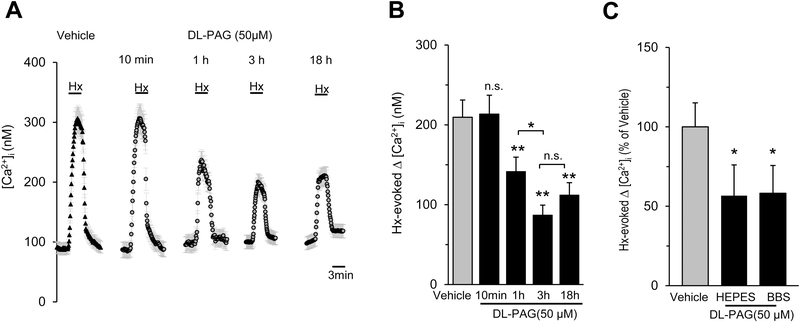

3.4.2. Effect of duration of pre-treatment with DL-PAG

To assess whether the effects of DL-PAG depend on the duration of pre-incubation, glomus cells were treated with 50μM DL-PAG for 10min, 1h, 3h and 18h prior to measuring the [Ca2+]i response to hypoxia. In cells treated with DL-PAG for 10 minutes, glomus cell [Ca2+]i responses to hypoxia were unaltered, whereas cells incubated with 1h or 3 h showed reduced [Ca2+]i response to hypoxia (Figs. 5A-B). Extending DL-PAG treatment for 18h had no further effect on the hypoxic response of glomus cells as compared to a 3h pre-treatment (Figs. 5A-B).

Figure 5. Effect of duration of pre-treatment with DL-PAG and buffering with either HEPES or bicarbonate buffered solutions (BBS) on [Ca2+]i responses to hypoxia.

A. Examples of hypoxia (Hx; pO2 = 37± 3mmHg)-induced [Ca2+]i responses of rat glomus cells treated with vehicle alone or pre-incubated with 50μM DL-PAG for different duration (10min, 1h, 3h, or 18h; n = 11–17 cells for each treatment). B. Average data (mean ± SEM) of hypoxia - induced [Ca2+]i responses of glomus cells pre-incubated with DL-PAG (50μM) for different duration and presented as stimulus-evoked response minus baseline levels (Δ[Ca2+]i, nM), n=45–63 cells for each treatment. C. Average data (mean ± SEM) showing the effect of DL-PAG (50μM) pre-incubated for 3h on hypoxia-induced [Ca2+]i responses of glomus cells superfused with either HEPES or bicarbonate buffered solutions (BBS), n=45–53 cells for each buffered solution. Horizontal bars in A represent the duration of the hypoxic challenge. *, P < 0.05 and **, P < 0.01. n.s., not significant (P > 0.05), compared with responses without DL-PAG treatment.

3.4.3. Effect of HEPES and bicarbonate buffered solutions

The effects of DL-PAG on hypoxia response were determined in cells superfused with either bicarbonate buffered solution bubbled with 5% CO2 or HEPES buffered solution. As shown in the figure 5C, the magnitude of DL-PAG induced inhibition of [Ca2+]i response to hypoxia was the same either by superfusing with HEPES or bicarbonate buffered solution.

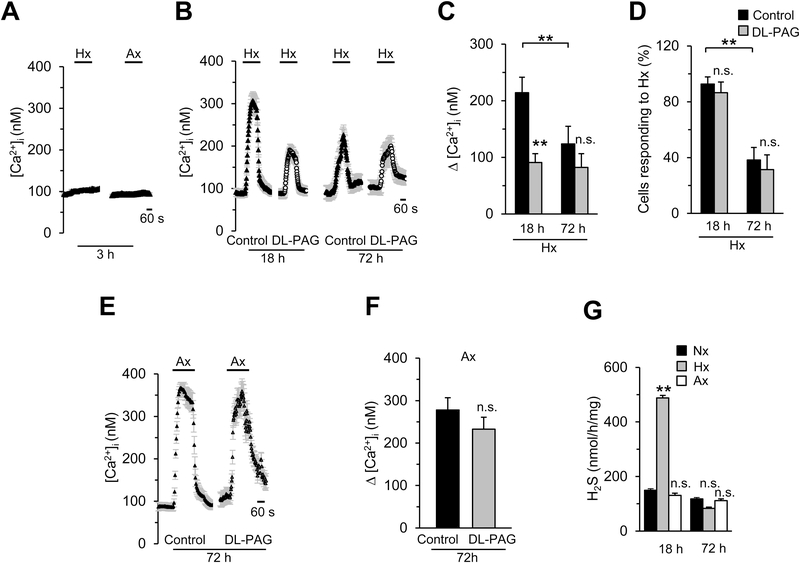

3.4.4. Effect of glomus cell culturing

The studies described thus far were conducted on glomus cells cultured overnight (~18 hours) after isolation from CBs. We then asked whether the duration of cell culturing affects the efficacy of DL-PAG on glomus cell response to hypoxia and anoxia. To this end, we compared [Ca2+]i responses to hypoxia and anoxia in glomus cells soon after isolation (3h) and cultured either overnight (~18h) or for 72h.

Glomus cells (n =78 cells) studied soon after isolation (3h) did not respond to either to hypoxia or anoxia with elevation of [Ca2+]i (Fig. 6A). Therefore, we did not further pursue assessing the role of H2S in these cells. The magnitude of [Ca2+]i response without DL-PAG and the number of cells responding to hypoxia both were markedly reduced in cells cultured for 72h as compared to cells cultured for ~18h (Figs. 6B-D). DL-PAG inhibited hypoxia-evoked [Ca2+]i elevation in glomus cells cultured for ~18h, whereas it had no effect in cells cultured for 72h (Figs. 6B-C). However, anoxia still produced a robust elevation of [Ca2+]i in cells cultured for 72h and this effect was unaffected by DL-PAG (Figs. 6 E-F). H2S generation by hypoxia was monitored in cells cultured for ~18h and 72h. Hypoxia markedly elevated H2S levels in cells cultured for 18h but not in cells cultured for 72h (Fig. 6G). In contrast, anoxia had no effect on H2S levels in cells cultured for either 18h or 72h (Fig. 6G).

Figure 6. Effect of culture condition of glomus cells on the efficacy of DL-PAG on [Ca2+]i responses to hypoxia and anoxia.

A. Examples of hypoxia (Hx; pO2 = 37± 3mmHg)- and anoxia (Ax; pO2 = 5±4 mmHg)-induced [Ca2+]i responses of rat glomus cells cultured for 3h. n = 78 cells. B. Examples of Hx-induced [Ca2+]i responses of rat glomus cells cultured for either 18h or 72h with and without 50μM DL-PAG, n = 13–21 cells for each treatment. C. Average data (mean ± SEM) of Hx-induced [Ca2+]i responses of glomus cells cultured for either 18h or 72h with and without 50μM DL-PAG, n =40–61 cells for each culture condition, and presented as stimulus-evoked response minus baseline levels (Δ[Ca2+]i, nM). D. Percentage of glomus cells responding to Hx after culturing for either 18h or 72h in the absence (control) and presence of 50 μM DL-PAG. Data were presented as mean ± SEM from 6 experiments. E. Examples of Ax-induced [Ca2+]i responses of rat glomus cells cultured for 72h with and without 50μM DL-PAG, n = 16 cells for each treatment. F. Average data (mean ± SEM) of Ax-induced [Ca2+]i responses of glomus cells cultured for 72h with and without 50μM DL-PAG (n =67 cells each), and presented as stimulus-evoked response minus baseline levels (Δ[Ca2+]i, nM). G. Average data (mean ± SEM) of H2S levels in the glomus cells cultured for either 18h or 72h and treated with either normoxia (Nx), Hx or Ax. Values were obtained from five experiments run in triplicate. **, P < 0.01 and n.s, not significant (P > 0.05), compared with control (in C, D & F) or Nx (in G).

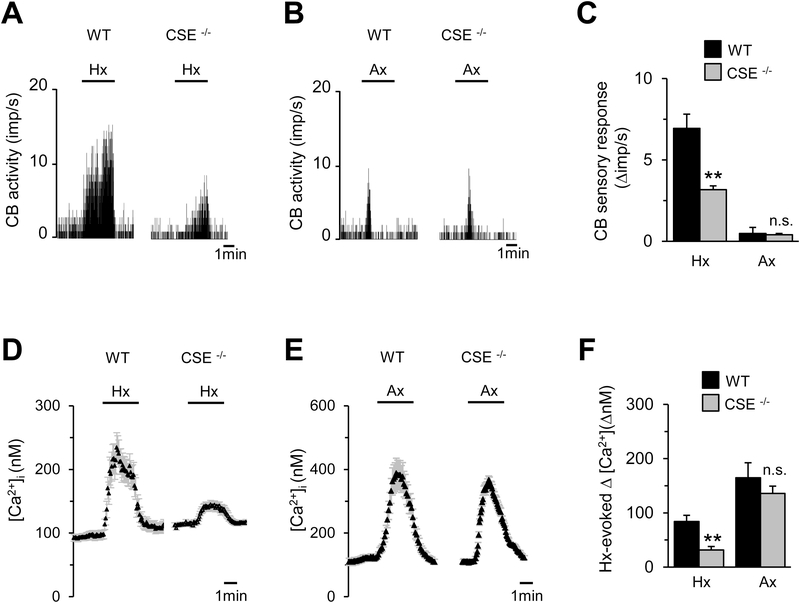

3.5. CB sensory nerve and glomus cell responses to hypoxia and anoxia in CSE null mice

To further determine the role of CSE-derived H2S in the CB responses to hypoxia and anoxia, studies were performed on wild-type and CSE null mice. Consistent with a previous study (Peng et al., 2010), the magnitude of CB sensory nerve excitation by hypoxia was markedly reduced in CSE null as compared to wild-type mice (Figs. 7A and C). Similar to the responses in rats, anoxia produced brief but modest excitation of the CB sensory nerve activity in both wild-type and CSE null mice (Figs. 7B and C ).

Figure 7. Carotid body sensory nerve and glomus cells responses to hypoxia and anoxia in CSE null mice.

A & B. Examples of carotid body sensory activity in response to hypoxia (Hx; pO2 = 37± 3mmHg) (A) or anoxia (Ax; pO2 = 5±4 mmHg) (B) in wild-type (WT) and CSE null mice. C. Average data (mean ± SEM) of carotid body sensory responses to Hx and Ax in mice and presented as stimulus-evoked response minus baseline levels (Δ impulse/sec), n=18 fibers each from 8 carotid bodies (each for WT and CSE null mice). D-E. Examples of [Ca2+]i responses to Hx (D) and Ax (E) of glomus cells from wild-type (WT, n= 5 cells) and CSE null (n=6 cells) mice. E. Average data (mean ± SEM) of Hx and Ax-evoked [Ca2+]i responses of glomus cells from wild-type (WT, n= 10 cells) and CSE null (n=14 cells) mice, and presented as stimulus-evoked response minus baseline levels (Δ[Ca2+]i, nM). Horizontal bars in A, B, D and E represent the duration of Hx and Ax. **, P < 0.01; and n.s., not significant (P > 0.05).

Consistent with a previous study (Makarenko et al., 2012), hypoxia increased [Ca2+]i in wild-type glomus cells and this response was attenuated in CSE null glomus cells (Figs. 7D and F). Anoxia evoked robust [Ca2+]i elevation in glomus cells of wild-type mice and this response was unaltered in CSE null mice (Figs. 7E-F).

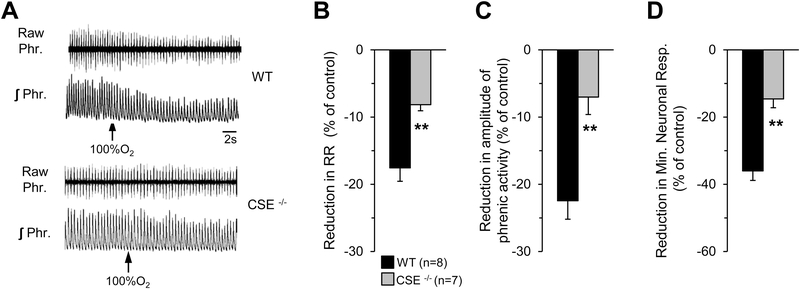

3.6. Impaired peripheral chemo receptor drive to breathing in CSE deficient mice

Brief (∼30 s) inhalation of 100% O2 decreases breathing, which was attributed to reduced sensory drive from the CB (DEJOURS, 1962). If CB sensitivity to O2 is altered in CSE-deficient mice, it should reflect in the breathing response to hyperoxia. This possibility was tested in age (6–8 weeks) and body weight matched wild-type (23.3±0.8 g; n=8) and CSE null mice (23.8±1.2g; n=7; wild-type vs CSE null mice P >0.05). Studies were performed on anesthetized, spontaneously breathing mice and efferent phrenic nerve activity was monitored as an index of neural respiratory drive. Baseline phrenic nerve activity was recorded while mice breathed room air and then 100% O2 was added for 30 seconds to the inspired air. In response to hyperoxia, neural respiration promptly reduced in wild-type mice and this effect was absent in CSE null mice (Fig. 8A). Average results showed that CSE null mice exhibited markedly attenuated neural breathing response to hyperoxia as compared to wild-type mice (Figs. 8B-D).

Figure 8. Efferent phrenic nerve responses to brief hyperoxia in CSE null mice.

A. Examples of efferent phrenic nerve responses to brief (30sec) exposure to 100%O2 (at arrow) in anesthetized, spontaneously breathing wild-type (WT) (Upper panel) and CSE null (Lower panel) mice. Raw Phr., action potentials of the phrenic nerve activity. ʃPhr., integrated efferent phrenic nerve activity. B-D. Average data (mean ± SEM) of hyperoxia-induced reduction in respiratory rate (RR; B), tidal amplitude of phrenic activity (C), and minute neuronal respiration (D) of WT (n=8) and CSE null (n=7) mice, expressed as percent of pre-hyperoxia controls **, P < 0.01.

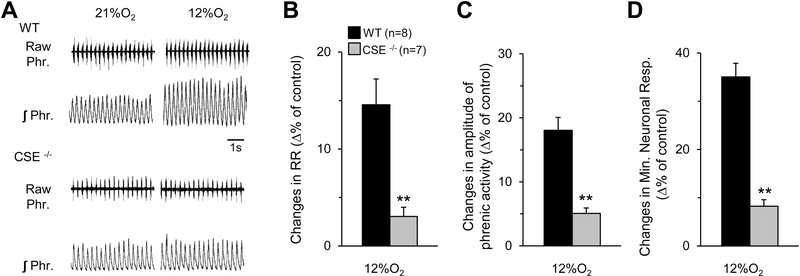

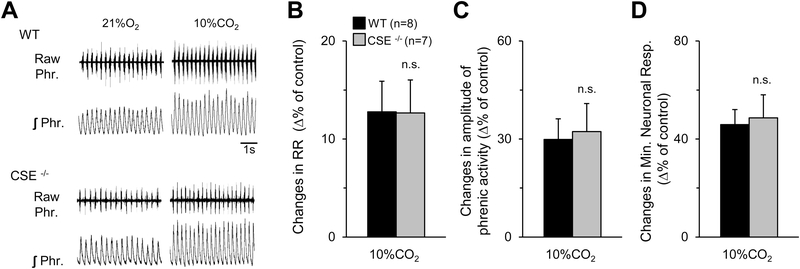

Stimulation of breathing by hypoxia is a hallmark manifestation of the CB chemo reflex (Kumar & Prabhakar, 2012). We determined the neural respiratory responses to hypoxia (FiO2 12% O2) and hypercapnia (FiCO2 10% CO2) in wild-type and CSE null mice. Hypoxia increased neural respiration (respiratory rate, tidal phrenic nerve activity, and minute neural respiration) in wild-type mice, and this response was nearly absent in CSE null mice (Figs. 9A-D). In contrast, both wild-type and CSE null mice responded to 10% CO2 with comparable stimulation of neural respiration (Figs. 10A-D).

Figure 9. Phrenic nerve responses to hypoxia in CSE null mice.

A. Example of efferent phrenic nerve activity during 21 and 12% inspired O2 in anesthetized, spontaneously breathing wild-type (WT) (Upper panel) and CSE null (Lower panel) mice. Raw Phr., action potentials of the phrenic nerve activity. ʃ Phr., integrated phrenic nerve activity. B-D. Average data (mean ± SEM) of changes in respiratory rate (RR; B), tidal amplitude of phrenic activity (C), and minute neuronal respiration (D) of WT (n=8) and CSE null (n=7) mice, presented as percent of 21% O2 breathing. **, P < 0.01.

Figure 10. Phrenic nerve responses to hypercapnia of WT and CSE null mice.

A. Example of efferent phrenic nerve activities during 21% O2 and 10% CO2 breathing in anesthetized, spontaneously breathing wild-type (WT) (Upper panel) and CSE null (Lower panel) mice. Raw Phr., action potentials of the phrenic nerve activity. ʃ Phr., integrated phrenic nerve activity. B-D. Average data (mean ± SEM) of respiratory rate (RR; B), amplitude of phrenic activity (C), and minute neuronal respiration (D) from WT (n=8) and CSE null (n=7) mice, presented as percent of 21% O2 breathing. n.s., not significant (P > 0.05).

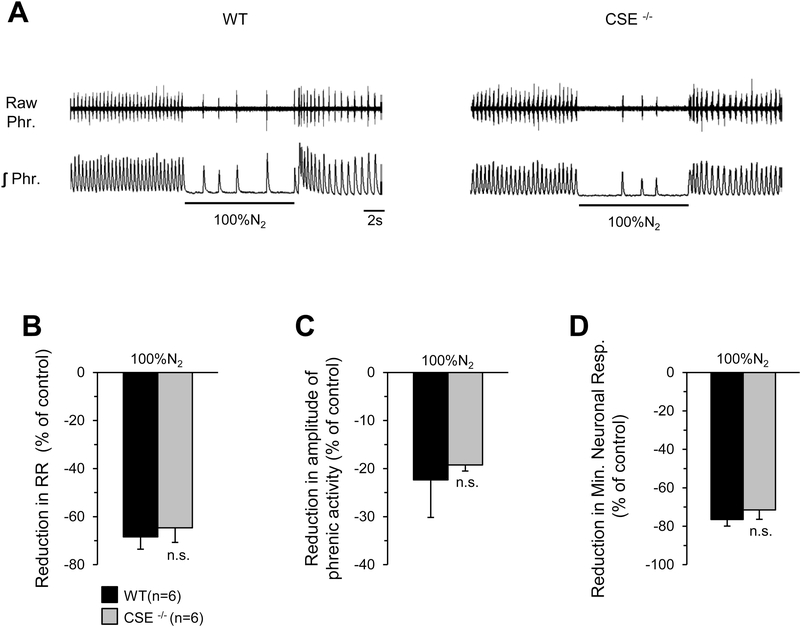

3.7. Depression of breathing by 100% N2 in Wild-type (WT) and CSE null mice

To determine the effect of “anoxia” on breathing, we examined efferent phrenic nerve activity in response to brief (10s) inhalation of 100% N2 in anesthetized, spontaneously breathing WT and CSE null mice. We chose 10s of inspired N2 because extending the duration to 1min resulted in irreversible respiratory depression and death of all mice studied. Anoxia with 100% N2 depressed neural respiration (respiratory rate, tidal phrenic nerve activity, and minute neural respiration) in both wild-type and CSE null mice and the magnitude of respiratory depression was comparable between both genotypes (Figs. 11 B-D).

Figure 11. Inhibition of phrenic nerve activity in response to anoxia (100%N2) in WT and CSE null mice.

A. Examples of efferent phrenic nerve responses to 100%N2 in anesthetized, spontaneously breathing wild-type (WT) (Left panel) and CSE null mice (Right panel). Raw Phr., action potentials of the phrenic nerve activity. ʃ Phr., integrated phrenic nerve activity. Horizontal bars represent the duration of the 100%N2 challenge. B-D. Average data (mean ± SEM) of respiratory rate (RR; B), tidal amplitude of the phrenic nerve activity (C), and minute neuronal respiration (D) in response to 100% N2 breathing of WT (n=6) and CSE null (n=6) mice, presented as percent of room air breathing n.s., not significant (P > 0.05) as compared to WT mice.

4. Discussion

Previous studies suggested a role for CSE-derived H2S in the CB response to hypoxia (Li et al., 2010; Peng et al., 2010; Telezhkin et al., 2010; Makarenko et al., 2012; Jiao et al., 2015; Yuan et al., 2015), a possibility that was recently questioned in two studies (Kim et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2017). While studies supporting a role for H2S in the CB used hypoxia as a stimulus (Peng et al., 2010; Makarenko et al., 2012; Yuan et al., 2015), investigations refusing this possibility utilized anoxia (0% O2) (Kim et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2017). We tested the hypothesis that the role of CSE-derived H2S in the CB depends on the severity of hypoxia. Our results demonstrate that the effects of hypoxia and anoxia on CB and breathing are distinctly different and CSE-derived H2S is involved in the chemoreceptor responses to hypoxia but not to the effects caused by anoxia.

4.1. CSE-derived H2S is important for CB sensory nerve excitation by hypoxia but not anoxia

Consistent with previous studies (Li et al., 2010; Peng et al., 2010), hypoxia-evoked CB sensory nerve excitation was markedly attenuated by DL-PAG, an inhibitor of CSE, and in CSE knockout mice. In contrast, anoxia despite producing much greater reduction in pO2 than hypoxia, produced only a modest CB sensory nerve excitation and this response was unaffected either by DL-PAG in rats and in CSE null mice. Furthermore, hypoxia but not anoxia increased H2S levels in the glomus tissue. These findings suggest that CSE-derived H2S plays an important role in CB sensory nerve excitation by hypoxia but not anoxia. The weak sensory excitation caused by anoxia is reminiscent of earlier studies on intact cat CBs (Hornbein et al., 1961; Hornbein & Ross, 1963; Fidone & Gonzalez, 1986). These studies reported that graded hypoxia up to arterial pO2 of ~30 mmHg leads to a progressive increase in the CB sensory nerve activity, and lowering arterial blood pO2 below 30 mmHg reduces the sensory nerve excitation.

4.2. CSE-derived H2S in CB glomus cell responses to hypoxia and anoxia

Low concentration of DL-PAG (50μM) markedly attenuated hypoxia-evoked [Ca2+]i elevation in rat glomus cells, a finding consistent with a previous study (Makarenko et al., 2012). The effects of 50μM DL-PAG were selective to hypoxia because at this concentration DL-PAG had no effect on [Ca2+]i responses to KCl, a non-selective depolarizing stimulus and cell viability was unaffected. Furthermore, the efficacy of DL-PAG depended on the solvent in which it was dissolved, required pre-incubation and duration of glomus cell culturing. Unlike the saline as a solvent, when dissolved in DMSO, DL-PAG was found to be remarkably ineffective in blocking H2S generation and [Ca2+]i elevation by hypoxia. It is likely that DMSO being a sulfur containing compound, might have acted as H2S and thereby masking the inhibitory effects of DL-PAG. The inhibitory effects of DL-PAG required pre-incubation of glomus cells for 1–3h. Why the pre-incubation is needed? DL-PAG is a propargyl derivative of the amino acid glycine. Since transporters are required for amino acid entry into cells, which might explain the need for pre-incubation. Kim et al.(2015) studied glomus cells 3h after isolation. However, under our experimental conditions, cells studied 3h after isolation neither responded to hypoxia nor anoxia. On the other hand, glomus cells cultured for 18h responded to hypoxia with increased H2S levels and [Ca2+]i elevation and these effects were inhibited by DL-PAG. In contrast, cells cultured 72h as compared to cells 18h in culture showed: a) markedly attenuated hypoxia-evoked [Ca2+]i elevation, b) no change in H2S levels in response to hypoxia, and c) no effect of DL-PAG on [Ca2+]i elevation by hypoxia. It is likely that prolonged culturing down regulated CSE in glomus cells, a possibility that requires further studies. Nonetheless, these findings suggest that glomus cells either too soon after isolation or after prolonged culturing are not appropriate for studying the effects of H2S synthesis inhibitors on response to hypoxia. Consistent with a previous study (Makarenko et al., 2012), hypoxia-evoked [Ca2+]i elevation was also markedly attenuated in CSE null glomus cells (Fig. 7). Together these findings demonstrate that CSE-derived H2S plays a role in glomus cell [Ca2+]i responses to hypoxia.

In contrast to hypoxia, anoxia-evoked greater [Ca2+]i elevation and this response was unaffected by 50μM DL-PAG. On the other hand, higher concentration of DL-PAG (300μM) either alone or in combination with 300μM AOAA, another H2S synthesis inhibitor consistently blocked anoxia-evoked [Ca2+]i elevation in glomus cells. However, the effects of high concentration of H2S synthesis inhibitors were non-specific as they also blocked [Ca2+]i elevation by KCl and were cytotoxic as evidenced by decreased cell viability. Our results with high concentration of H2S synthesis inhibitors differ from the report by Kim et al. (2015), who found no effects of either 300μM of DL-PAG alone or in combination with 300μM AOAA. The ineffectiveness of DL-PAG reported by Kim et al (2015) is conceivably due to the fact that it was dissolved in DMSO, which we found reduces its efficacy in inhibiting H2S synthesis. These findings taken together with the observation that [Ca2+]i response to anoxia was unaltered in CSE null glomus cells suggest that CSE-derived H2S do not contribute to glomus cells response to anoxia.

It is intriguing that anoxia although caused greater [Ca2+]i elevation than hypoxia in glomus cells, yet produced only a weak stimulation of the sensory nerve activity. It may be that pronounced [Ca2+]i elevation by anoxia may have resulted in greater release of inhibitory chemical messengers than hypoxia, causing suppression of the sensory discharge. Alternatively, dithionite and glucose oxidase combined with catalase, which were used for generating anoxia, might have directly affected the excitability of the sensory nerve. Assessing these possibilities is beyond the scope of current study and requires further investigation.

4.3. CSE-derived H2S contributes to HVR but not to respiratory depression by anoxia

Hypoxic ventilatory response (HVR) is a hallmark of the CB chemo reflex. Wang et al. (2017) reported unaltered HVR in CSE null as compared to wild-type mice, a finding opposite to that reported by Peng et al. (2010). Since both groups (Peng et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2017) studied CSE null mice developed by Dr. Rui Wang, the conflicting results are unlikely due to differences in the back ground strains of the mutant mice. Both studies (Peng et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2017) monitored breathing by whole body plethysmograph, which requires normalization of the data with body weights. The CSE null mice studied by Wang et al (Wang et al., 2017) had remarkably lower body weights than wild-type mice, a phenotype that was neither seen by Peng et al (2010) nor by Rui Wang and his co-workers ((Yang et al., 2018); see Fig. 6A), who developed these mice. Although after normalization with body weights, Wang et al (2017) found no difference in HVR between CSE null and Wild-type mice, but without normalization, the HVR data of CSE null mice reported by Wang et al (2017, Table 1) is similar to that reported by Peng et al. (2010).

To circumvent the limitations of the plethysmography approach, efferent phrenic nerve activity was monitored as an index of neural respiration in wild-type and CSE null mice. The magnitude of reduction in breathing by hyperoxia is often considered as an indirect measure of CB sensitivity to O2 (DEJOURS, 1962). Breathing responses to hyperoxia were attenuated in CSE null mice as compared to wild-type control mice indicating blunted CB sensitivity to O2. Moreover, HVR, which is an index of the CB chemo reflex, was also markedly reduced in CSE null mice. However, breathing response to CO2 was unaltered in CSE null mice, suggesting that genetic deletion of CSE selectively impaired contribution of the CB to stimulation of breathing by hypoxia. In striking contrast to hypoxia, mimicking anoxia with brief inhalation of 100% N2 markedly inhibited breathing in both wild-type and CSE null mice, indicating CSE-derived H2S do not contribute to anoxia-evoked depression of breathing.

In summary, the present results demonstrate strikingly different effects of hypoxia and anoxia on CB sensory nerve, glomus cells and breathing and further show that CSE-derived H2S plays a role in CB and CB chemo-reflex responses to hypoxia but not anoxia.

Highlights.

Hypoxia (pO2 ~37 mmHg) increased H2S levels in the carotid body (CB), sensory nerve activity, and elevated [Ca2+]i in glomus cells, and these responses were inhibited by DL-propargylglycine (DL-PAG), an inhibitor of H2S synthesis and in mice lacking cystathionine-γ-lyase (CSE), a major H2S synthesizing enzyme in the CB.

In striking contrast, anoxia (pO2~5 mmHg) had no effect on H2S levels in the CB, and produced only weak sensory excitation of the CB, but robust elevation of [Ca2+]i in glomus cells. The responses to anoxia were unaffected by DL-PAG and in CSE knockout mice.

Hypoxia stimulated and anoxia inhibited breathing. The effects of hypoxia on breathing were absent, whereas depressed breathing were unaffected in CSE knockout mice.

These results demonstrate hypoxia and anoxia are not similar stimuli for studying CB physiology and suggest that H2S contributes to CB response to hypoxia but not to anoxia.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants P01-HL-90554.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Buckler KJ. (2012). Effects of exogenous hydrogen sulphide on calcium signalling, background (TASK) K channel activity and mitochondrial function in chemoreceptor cells. Pflugers Arch 463, 743–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang AJ. (2017). Acute oxygen sensing by the carotid body: from mitochondria to plasma membrane. J Appl Physiol (1985) 123, 1335–1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEJOURS P (1962). Chemoreflexes in breathing. Physiol Rev 42, 335–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidone SJ & Gonzalez C. (1986). Initiation and control of chemoreceptor activity in the carotid body In Handbook of Physiology- The Respiratory System- Control of Breathing, pp. 247–312. American Physiological Society, Bethesda, MD, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez C, Almaraz L, Obeso A & Rigual R. (1994). Carotid body chemoreceptors: from natural stimuli to sensory discharges. Physiol Rev 74, 829–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornbein TF, Griffo ZJ & Roos A. (1961). Quantitation of chemoreceptor activity: interrelation of hypoxia and hypercapnia. J Neurophysiol 24, 561–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornbein TF & Ross A. (1963). Specificity of H ion concentration as a carotid chemoreceptor stimulus. Journal of Applied Physiology 18, 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao Y, Li Q, Sun B, Zhang G & Rong W. (2015). Hydrogen sulfide activates the carotid body chemoreceptors in cat, rabbit and rat ex vivo preparations. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 208, 15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Kim I, Wang J, White C & Carroll JL. (2015). Hydrogen sulfide and hypoxia-induced changes in TASK (K2P3/9) activity and intracellular Ca(2+) concentration in rat carotid body glomus cells. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 215, 30–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline DD, Yang T, Huang PL & Prabhakar NR. (1998). Altered respiratory responses to hypoxia in mutant mice deficient in neuronal nitric oxide synthase. J Physiol 511 ( Pt 1), 273–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P & Prabhakar NR. (2012). Peripheral chemoreceptors: function and plasticity of the carotid body. Comprehensive Physiology 2, 141–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard EM, Salman S & Nurse CA. (2018). Sensory Processing and Integration at the Carotid Body Tripartite Synapse: Neurotransmitter Functions and Effects of Chronic Hypoxia. Front Physiol 9, 225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Sun B, Wang X, Jin Z, Zhou Y, Dong L, Jiang LH & Rong W. (2010). A crucial role for hydrogen sulfide in oxygen sensing via modulating large conductance calcium-activated potassium channels. Antioxid Redox Signal 12, 1179–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Barneo J, González-Rodríguez P, Gao L, Fernández-Agüera MC, Pardal R & Ortega-Sáenz P. (2016). Oxygen sensing by the carotid body: mechanisms and role in adaptation to hypoxia. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 310, C629–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarenko VV, Nanduri J, Raghuraman G, Fox AP, Gadalla MM, Kumar GK, Snyder SH & Prabhakar NR. (2012). Endogenous H2S is required for hypoxic sensing by carotid body glomus cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 303, C916–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Y-J, Nanduri J, Raghuraman G, Souvannakitti D, Gadalla MM, Kumar GK, Snyder SH & Prabhakar NR. (2010). H2S mediates O-2 sensing in the carotid body. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107, 10719–10724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng YJ, Makarenko VV, Nanduri J, Vasavda C, Raghuraman G, Yuan G, Gadalla MM, Kumar GK, Snyder SH & Prabhakar NR. (2014). Inherent variations in CO-H2S-mediated carotid body O2 sensing mediate hypertension and pulmonary edema. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S A 111, 1174–1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng YJ, Overholt JL, Kline D, Kumar GK & Prabhakar NR. (2003). Induction of sensory long-term facilitation in the carotid body by intermittent hypoxia: implications for recurrent apneas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100, 10073–10078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakar NR, Peng YJ, Yuan G & Nanduri J. (2018). Reactive oxygen radicals and gaseous transmitters in carotid body activation by intermittent hypoxia. Cell Tissue Res 372, 427–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telezhkin V, Brazier SP, Cayzac SH, Wilkinson WJ, Riccardi D & Kemp PJ. (2010). Mechanism of inhibition by hydrogen sulfide of native and recombinant BKCa channels. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 172, 169–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Hogan JO, Wang R, White C & Kim D. (2017). Role of cystathionine-γ-lyase in hypoxia-induced changes in TASK activity, intracellular [Ca2+] and ventilation in mice. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 246, 98–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G, Ju Y, Fu M, Zhang Y, Pei Y, Racine M, Baath S, Merritt TJS, Wang R & Wu L. (2018). Cystathionine gamma-lyase/hydrogen sulfide system is essential for adipogenesis and fat mass accumulation in mice. Biochim Biophys Acta 1863, 165–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan G, Vasavda C, Peng YJ, Makarenko VV, Raghuraman G, Nanduri J, Gadalla MM, Semenza GL, Kumar GK, Snyder SH & Prabhakar NR. (2015). Protein kinase G-regulated production of H2S governs oxygen sensing. Sci Signal 8, ra37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]