Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Cumulative sum (CuSum) is a real-time proficiency-monitoring tool adapted for simulation-based training. This study’s objective was to investigate long-term outcomes of a double blinded, randomized control trial conducted with medical students assessing CuSum-guided curriculum against volume-based standards. The trial found a nearly 20% reduction in practice time to reach proficiency using the CuSum curriculum but long-term effects of decreased practice volume on proficiency is unknown.

DESIGN

Prior participants completed a survey assessing confidence, exposure, and feedback at 12 to 18 months following trial completion. They underwent retention testing of suturing, intubation, and central venous catheter placement (CVC), which was video-recorded and assessed by an expert evaluator. Baseline characteristics among repeat subjects were compared using chi-squared tests. Retention and initial trial outcome were compared using paired parametric statistical methods.

SETTING

The study was conducted at a major tertiary care center and training hospital.

PARTICIPANTS

Medical students, which completed the initial randomized control trial were eligible for enrollment. A total of 30/46(65%) responded to the survey, whereas 33/46(72%) completed retention testing.

RESULTS

Average scores and decay in procedural tasks over time for suturing, intubation and CVC were 91.6% (−4.7%), 86.1% (−4.1%), and 76.2% (−14.8%), respectively. Compared to the control group, the CuSum group mean difference in retention evaluation scores was −5.6% (p = 0.12). Confidence was not associated with initial or retention testing performance in any procedural task. Higher confidence was associated with additional exposure to the procedural task in suturing and intubation (p = 0.03 and p = 0.02, respectively). For intubation, higher confidence was reported by participants who received positive feedback (p = 0.01), and those assigned to the volume-based training arm (p = 0.03).

CONCLUSION

CuSum-guided training was equivalent to conventional training for suturing, intubation, and CVC. These findings importantly suggest medical students can retain competency in invasive surgical tasks with modest decay in proficiency over time regardless of initial training method.

Keywords: simulation training, competency-based curriculum, cumulative sum, surgical education, medical student education

INTRODUCTION

Improving resident preparedness for invasive procedures has received increasing attention following resident work-hour restrictions. Focus on patient outcomes has increased as performance is increasingly linked to reimbursement and quality reporting.1,2 Evidence of the un intentional effect of these policy changes resides within a recent survey of fellowship directors, which reported concern in operative decision-making and skill of recent general surgery residency graduates.3 Though multifactorial, this is likely a contributing factor for the increase in the number of fellowship applicants in the past decade. Following the 2003 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) work-hour restrictions, performance on certification examinations has decreased.4 To address these pressures, training programs have expanded the role of simulation training and have developed competency-based curriculum to assess progress and facilitate skills acquisition.5–7

We previously undertook a 2-year, double-blinded, randomized control trial, which assessed the effectiveness of a curriculum developed to teach medical students 3 procedural tasks: suturing and knot tying, intubation, and central venous catheterization (CVC). The initial trial compared proficiency rates and practice patterns between traditional volume-based training standards vs an objective and adaptive measure called cumulative sum (CuSum). The initial trial observed a nearly 20% reduction in practice time needed to reach proficiency in the CuSum arm. Additionally, high rates of technical proficiency were attained across the various procedural arms in both study arms.8

This study’s purpose was to investigate the long-term outcomes of this randomized study. We hypothesized that there would be no significant difference in long-term performance between participants trained using CuSum-based method and those trained using volume-based metrics. Our secondary objective was to characterize whether these simulation experiences affected participants’ confidence level in performance of the targeted skills.

METHODS

CuSum is a quality-control tool adapted to facilitate real-time proficiency monitoring for simulation-based training and individualized training curricula. Notable advantages to using CuSum in medical school education and surgical training is its ability to depict individual participant learning curves and its high sensitivity to detect variations in performance including relapses in proficiency over time.9–11

A detailed description of the methodology for the initial randomized control trial has been published.8 In brief, preclinical medical students were randomized into CuSum-based vs volume-based arms. Participants underwent simulation training on suturing, intubation, and CVC skills. Volume-based participants were required to complete a defined number of hours per skill while Cusum participants practiced until proficiency was attained according to a CuSum computerized algorithm. Performance was assessed against a checklist of a priori objective measures for each procedural task and scored via expert evaluation.8

Modification of the institutional internal review board approval to conduct the follow up study was obtained (2013-0246-00) and verbal and written consent of voluntary participation in the study was received from all participants. Prior participants were contacted following completion of their surgical clerkship rotations. Time lapse from trial completion ranged between 12 and 18 months. Gender, initial study arm designation, and initial trial scores were collected for each participant. A 7-item survey was administered to participants to assess the participants’ perceived confidence, extent and type (either patient-based or simulation-based) of subsequent interval exposure, and rotation feedback for each procedural task (Appendix A). Survey responses pertaining to confidence were based on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1: very confident – participant can comfortably perform independently to 5: not confident at all. High confidence level was defined as a 1 to 2 on the Likert scale, whereas 3 to 5 was interpreted as a lack of meaningful confidence for the purposes of analysis.

The definition for substantial subsequent experience following the initial trial varied by procedural task. For suturing, substantial experience was considered extensive patient-based experience; whereas for intubation, substantial experience could be either extensive patient-based or simulation-based experience. Substantial experience level for CVC was defined as any subsequent hands-on exposure after completion of the initial trial. Feedback was classified as either positive or negative and limited to suturing and intubation based on scarcity of practical opportunities for performance of CVC during surgical clerkships.

Additionally, participants underwent triplicate retention testing of suturing, intubation, and CVC. The first attempt was performed as a practice run. Before the subsequent 2 attempts, participants were allowed to review the procedural checklist for each respective task (Appendix B). This review of the checklists was allowed in order to better reflect real-world practice/behavior. Each participant attempt was video-recorded and de-identified for assessment by a blinded expert surgical faculty. For each procedural task, the evaluator’s scores were averaged combining the practice run and latter 2 attempts following checklist review.

Survey and retention testing results were merged with available participant sex, initial study arm designation, and the initial trial scores. Chi-squared and 1-way ANOVA tests were performed to compare gender, study arm composition, and initial trial performance scores to assess similarities between the initial trial participants and participants completing the survey and retention testing. Initial trial scores and retention testing scores were compared using paired parametric statistical methods. Associations between confidence level and potentially impactful variables such as study arm designation, extent of subsequent interval exposure, rotation feedback, and performance scores either from the initial study or retention testing were assessed using univariate analyses. All analyses were performed using Stata/SE 15.0 (StataCorp 2017, College Station, TX). Significance was defined as a p value of less than 0.05.

RESULTS

Of the 46 participants that participated in the initial trial and met our inclusion criteria, 30/46 (65%) responded to the survey, whereas 33/46 (71.7%) completed retention testing. Four participants were excluded from the follow up study based on academic withdrawal or leave, or because they did not complete the original trial. We compared the distribution of gender and study designation to determine whether a representative cohort was achieved in the survey responses and retention testing. Table 1 shows the number and percentage of participants by gender and initial study arm. We found no difference in gender or study arm designation between the initial trial and either the survey follow-up cohort or retention testing cohort, (p = 0.93 and p = 0.89, respectively). Overall initial trial performance scores did not differ between the cohorts. This remained true even when initial trail performance scores were stratified by procedural task.

TABLE 1.

Participant Characteristics From the Initial Trial, Follow Up Survey, and Retention Testing

| Initial Trial | Follow Up Survey | Retention Testing | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total, # (%) | 46 | 30 (65%) | 33 (71.7%) | – |

| Study arm | 0.89 | |||

| Volume based, # (%) | 23 (53.5%) | 17 (58.6%) | 18 (58.1%) | |

| CuSum based, # (%) | 20 (46.5%) | 12 (41.4%) | 13 (41.9%) | |

| Gender, male, # (%) | 32 (71.1%) | 22 (73.3%) | 24 (75%) | 0.93 |

| Overall initial trial score, % (SD) | 92.5 (4.9) | 93.7 (4.0) | 92.3 (5.0) | 0.47 |

| Suturing, # (SD) | 96.3 (4.5) | 97.5 (3.0) | 96.2 (5.0) | 0.39 |

| Intubation, # (SD) | 90.2 (9.6) | 91.5 (8.6) | 89.3 (9.8) | 0.66 |

| CVL placement, # (SD) | 91.0 (7.2) | 92.0 (6.2) | 91.5 (7.0) | 0.82 |

SD, standard deviation.

A composite score off all 3 tasks showed that the overall average (standard deviation) following retention testing was 84.4% (9.8) compared to 92.3% (5.0) after the initial trial, (a −7.9 percentage point difference, p < 0.001). When stratified by procedural tasks, significant decreases in average scores (standard deviation) were observed for suturing and CVC placement, 96.2 (5.0) initial suturing score vs 91.3 (8.3) suturing retention score, p = 0.006, and 91.5 (7.0) initial CVC score vs 76.0 (21.4) CVC retention score, p < 0.001 (Table 2). Additionally, we observed significant differences between the initial trial mean scores and retention testing scores by study arm, 91.3% initial vs 87.0% retention (p = 0.011) for the volume-based training arm, and 94.5% initial vs 81.4% retention (p = 0.002) for the CuSum-based training arm (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Participant Mean Scores From the Initial Trial vs Retention Testing by Procedural Task and Study Arm

| Initial Trial Score | Retention Score | Mean Score Difference | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall score, % (SD) | 92.3 (5.0) | 84.4 (9.8) | −7.9 (9.9) | <0.001 |

| Suturing, % (SD) | 96.2 (5.0) | 91.3 (8.3) | −4.9 (9.5) | 0.006 |

| Intubation, % (SD) | 89.3 (9.8) | 86.0 (9.9) | −3.3 (11.5) | 0.113 |

| CVC placement, % (SD) | 91.5 (7.0) | 76.0 (21.4) | −15.6 (20.3) | <0.001 |

| Study arm | ||||

| Volume based, % (SD) | 91.3 (4.9) | 87.0 (6.7) | −4.4 (1.5) | 0.011 |

| CuSum based, % (SD) | 94.5 (4.0) | 81.4 (12.6) | −13.0 (3.4) | 0.002 |

SD, standard deviation.

Table 3 shows mean the retention scores by study arm and by procedural task. For suturing, intubation, and CVC by study arm, the mean differences in scores were 91.0% CuSum-based training arm vs 91.5% volume-based training arm (p = 0.89), 84.2% CuSum-based training arm vs 88.0% volume-based training arm (p = 0.30), and 69.1% Cusum-based training arm vs 81.5% volume-based training arm (p = 0.12), respectively. There was no statistically significant difference between the overall composite score from retention testing by initial training method, 81.4% CuSum-based training arm vs 87.0% volume-based training arm (p = 0.12).

TABLE 3.

Overall Mean Retention Scores by Study Arm and Stratified by Procedural Task

| Overall Score | Suturing | Intubation | CVC Placement | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study arm | ||||

| CuSum based, % (SD) | 81.4 (12.6) | 91.0 (9.5) | 84.2 (7.4) | 69.1 (25.8) |

| Volume based, % (SD) | 87.0 (6.7) | 91.5 (7.9) | 88.0 (11.2) | 81.5 (17.0) |

| Mean difference, % | −5.6 | −0.5 | −3.8 | −12.4 |

| p value | 0.12 | 0.89 | 0.30 | 0.12 |

SD, standard deviation.

From the survey, 22/30 (73.3%) of participants reported high confidence levels with suturing and knot tying, 18/30 (60.0%) with intubation, and 7/30 (23.3%) with CVC (Table 4). For suturing, 10/30 (33.3%) reported extensive patient-based exposure and 26/30 (86.7%) received positive feedback. For intubation, 11/30 (36.7%) reported extensive patient-based or simulation based exposure following the trial completion and 14/30 (46.7%) received positive feedback.

TABLE 4.

High Reported Confidence Level Compared by Trial Arm, Additional Exposure, Feedback, Initial Scores, and Retention Testing Scores by Procedural Task

| Suturing | Intubation | CVC Placement | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Confidence level, # (%) | 22/30 (73.3) | 18/30 (60.0) | 7/30 (23.3) |

| Trial arm | |||

| Volume based, # (%) | 14/17 (82.4) | 13/17 (76.5) | 2/17 (11.8) |

| CuSum based, # (%) | 8/12 (66.7) | 4/12 (33.3) | 5/12 (41.7) |

| p value | 0.40 | 0.03 | 0.09 |

| Additional exposure | |||

| Yes, # (%) | 10/10 (100) | 10/11 (91) | 3/16 (18.8) |

| No, # (%) | 12//20 (60) | 8/19 (42.1) | 4/14 (28.6) |

| p value | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.68 |

| Feedback | |||

| Positive, # (%) | 20/26 (76.9) | 12/14 (85.7) | NA |

| Negative/none, # (%) | 2/4 (50) | 6/16 (37.5) | NA |

| p value | 0.28 | 0.01 | NA |

| Retention scores | |||

| Yes, % (SD) | 91.0 (8.6) | 84.6 (10.1) | 76.3 (26.0) |

| No, % (SD) | 92.8 (9.2) | 90.1 (8.6) | 75.2 (22.9) |

| p value | 0.63 | 0.16 | 0.92 |

| Initial RCT scores | |||

| Yes, % (SD) | 97.9 (3.0) | 90.7 (9.7) | 93.7 (7.6) |

| No, % (SD) | 96.5 (2.8) | 92.6 (6.8) | 91.5 (5.8) |

| p value | 0.27 | 0.57 | 0.43 |

SD, standard deviation.

Although for CVC, 16/30 (53.3%) reported some degree of additional exposure, either patient-based or simulation-based. No participants reported receiving any feedback, either positive or negative for CVC placement.

A high reported confidence level was not associated with performance scores either from the initial trial or retention testing for any of the procedural tasks. There existed a positive association between high reported confidence and additional exposure/experience with suturing and knot tying (p = 0.03) and intubation (p = 0.02). Additionally, confidence with intubation was associated with receiving positive feedback during clerkship rotations (p = 0.01) and being in the volume-based study arm (p = 0.03). There was no other significant difference seen in rates of high reported confidence, additional exposure, or positive feedback obtained during their clerkship rotations between the CuSum-based training and volume-based training arm (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

This study captures the long-term results of a comparison between an adaptive, proficiency-based curriculum and a traditional volume-based protocol. We found that it is possible to effectively train medical students to perform invasive tasks and that competency may be retained with minimal exposure, provided that initial training was meaningfully monitored and thoroughly evaluated. After more than a year since training, medical students experienced a slight decrease in skill proficiency. Proficiency did not depend on initial training method, which supports continued exploration of CuSum for real-time monitoring and objective feedback to guide the training of technical skills, as the CuSum method demonstrated a significant reduction in time required to learn complex tasks.8 Specific to medical students, these findings suggest a value in training students before graduation in certain technical skills needed during internship through a longitudinal simulation curriculum throughout medical school education vs targeted clinical electives such as surgery boot camp or surgical clerkships.12

Increasingly, CuSum is being applied in simulation training scenarios and skill evaluations in the clinical setting. CuSum has been used to calculate the average practice time needed to attain proficiency in technical procedures such as endoscopy and laparoscopic fundamentals.11,13,14 In all cases, CuSum captures variability in learning curves and relapses in proficiency on an individual basis in a manner that is not resource intensive. Additionally, risk-adjusted CuSum has been used to monitor surgical performance for clinical outcomes including mortality. In such instances, CuSum has again shown earlier detection of lapses in performance but also quantitative responses to quality improvement interventions.15

The optimum maintenance training regimen for long-term surgical skill retention remains unclear.16 Doumouras and Engels17 noted no decay in early crisis nontechnical skills following a 2-year high-fidelity simulation experience 12 months following course completion. Hubert et al.18 also did not find deterioration in performance levels of cricothyrotomy in anesthesiology residents at 3-, 6-, or 12-months. Although CuSum does not inform the intersession spacing period, it may be used to determine the number of training sessions needed based on the individual’s learning curve.

Self-guided learning may be enhanced through the setting of process goals. Brydges et al.19 demonstrated better acquisition of technical skills during self-directed learning when process goals were made explicitly available compared with outcomes goals. Prior research has shown CuSum is adept as a performance monitoring tool using clinical outcomes.15 The procedure checklists generated for our study contained a mixture of both process and outcome goals. Thus, our findings suggest the ability for CuSum to assess proficiency in self-guided learning using process goals if it is incorporated into a prescribed checklist.14

The surgical education literature including applications of CuSum-based learning assessments has focused on initial proficiency rather than long-term retention. Similar to our findings, Madani et al.20 found that a self-guided, goal-directed curriculum can improve knowledge retention up to 1-year following training. Additionally, we demonstrated the added feasibility of using CuSum to assess for skill decay. In a systematic review on surgical skill decay, Cecilio-Fernandes et al.16 found spaced practice to improve surgical skill retention in a variety of skills ranging from laparoscopic transfers to suturing end-to-end anastomoses. As such, the distribution of skill learning over a 6-week period in the initial study with multiple sessions may have contributed to the degree of retention observed in our study.

High variability was found among the procedural tasks with regard to subsequent experience, confidence levels, and rotation feedback. We found no correlation between confidence level and objective performance of the procedural task as assessed by a blinded independent expert reviewer. Instead, for suturing and endotracheal intubation, high self-reported confidence was associated with further patient-based or simulation-based experience. Dehmer et al.21 reported similar findings on a medical student survey with a variety of invasive procedural skills, which included suturing, intubation, and CVC placement.

The current gold standard for skill evaluation requires trained or expert personnel and is therefore resource intensive. Opportunities for feedback during monitored practice or clinical care are dictated largely by the availability of the instructor. Thus, it is necessary for students and trainees to employ objective methods either in simulation training or in clinical practice that facilitates skill acquisition and retention. Particularly for relatively common procedures or advanced, but rare procedures, a CuSum-based curriculum could be completed independently through self-directed learning and a graph of the trainee’s learning curve used as feedback of mastery or as we have demonstrated, to review proficiency months to years after initial training. A similar algorithm used by Stefanidis et al.22 showed that simulation learning can translate into improved operative performance for laparoscopic skills. An added benefit of CuSum would be an appropriate allocation of time for simulation practice as dictated by an objective measure in real-time.

LIMITATIONS

There are several important limitations to our study. The randomized control trial was not powered to determine differences in long-term skills retention. To mitigate an attrition rate of approximately 30 percentage, we assessed the comparability of the follow up cohorts and original study participants and found similar gender, study arm distributions, and initial performance scores. However, the sample size prohibited multivariable logistic regression modeling to further characterize significant findings. Regarding measures of experience, reliance on subjective measures from survey questions is vulnerable to well-established biases such as recall bias and testing threat. Attempts to define the varying degrees of exposures found in the survey were not made upfront and could not be applied retroactively. The expert evaluator was blinded to the identity and initial training method of the participants to provide consistency in the performance scoring method between the initial trial and retention testing. The working hypothesis was that there was no difference in the long-term performance of the procedural tasks by training method, a result that could introduce evaluator bias even with a blinded evaluator.

Finally, it is not possible to compare the levels of technical skill degradation noted in our study to prior cohorts that have completed the proficiency-based curriculum as this is first cohort to complete the curriculum and first to have long-term retention assessed. An extensive literature review to assess average degradation rates of basic surgical skills was undertaken and the relevant literature mentioned above. The time elapsed between retention testing and closure of the initial trial or completion of their surgical clerkship was not collected. It is possible that the performance scores observed in retention testing may vary to some extent by time. As participants were also exposed to a variable degree of subsequent exposures to each procedural task, it is difficult to tease out the effect of elapsed time vs additional experience on the retention performance scores.

CONCLUSIONS

It is possible to train medical students to perform invasive clinical tasks that are normally not part of their preclinical curriculum in a manner that assures a high level of competency across learners. Furthermore, students will retain proficiency in these tasks over long periods of time, suggesting a place for simulation training in the preclinical curriculum. Procedural skills acquired through an adaptive, competency-driven curriculum have equivalent durability as those acquired through a volume-based training regimen. In an era with increasing need for self-guided, goal-directed learning, implementing CuSum for psychomotor skill acquisition and monitoring for skill decay can serve as an important objective adjunct in simulated or patient scenarios.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health [Grant T32HL007849] (to AGR) and institutional support from the Academy of Distinguished Educators, University of Virginia (to SKR).

APPENDIX A. ONLINE SURVEY TOOL

Name:

Original study ID number:

Email:

-

How confident are you with regards to figure-of-eight suturing and knot-tying?

-

How confident are you with regards to intubation via direct laryngoscopy?

-

How confident are you with regards to central venous catheterization?

-

Have you received comments feedback from others regarding any of the BMIST (name of original trial) skills?

Under ‘other’, please comment on the feedback you received, Be specific/subjective!

Multiple answer options include:-

–Suturing: positive feedback

-

–Suturing: negative feedback

-

–Intubation: positive feedback

-

–Intubation: negative feedback

-

–CVC: positive feedback

-

–CVC: negative feedback

-

–Other

-

–

-

How much exposure have had in Suturing since participating in the study?

Select all that apply.

Multiple answer options include:-

–Extensive patient-based experience

-

–Occasional patient-based experience

-

–Extensive simulation-based experience

-

–Occasional simulation-based experience

-

–Little to no additional experience

-

–

-

How much exposure have you had in Intubation since participating in the study?

Select all that apply.

Multiple answer options include:-

–Extensive patient-based experience

-

–Occasional patient-based experience

-

–Extensive simulation-based experience

-

–Occasional simulation-based experience

-

–Little to no additional experience

-

–

-

7: How much exposure have in central venous catheterization since participating in the study?

Select all that apply.

Multiple answer options include:-

–Extensive patient-based experience

-

–Occasional patient-based experience

-

–Extensive simulation-based experience

-

–Occasional simulation-based experience

-

–Little to no additional experience

-

–

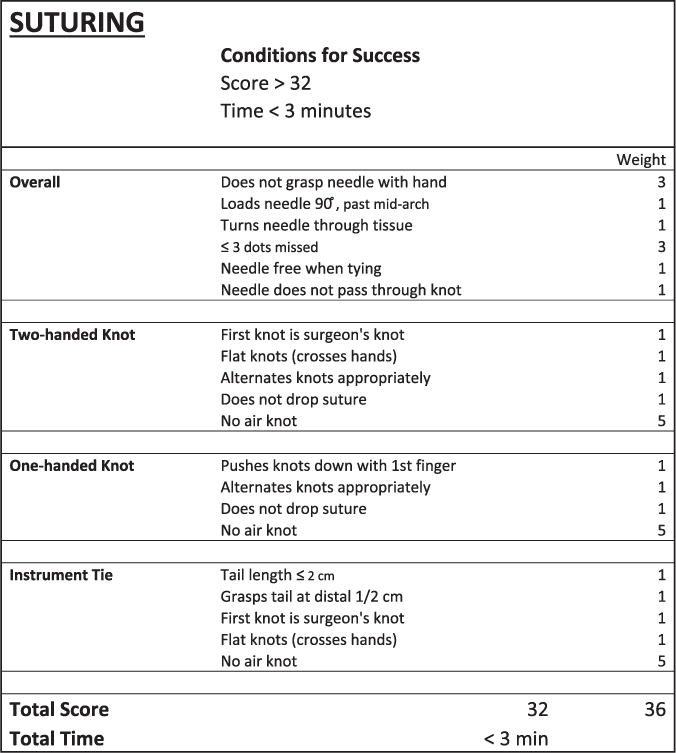

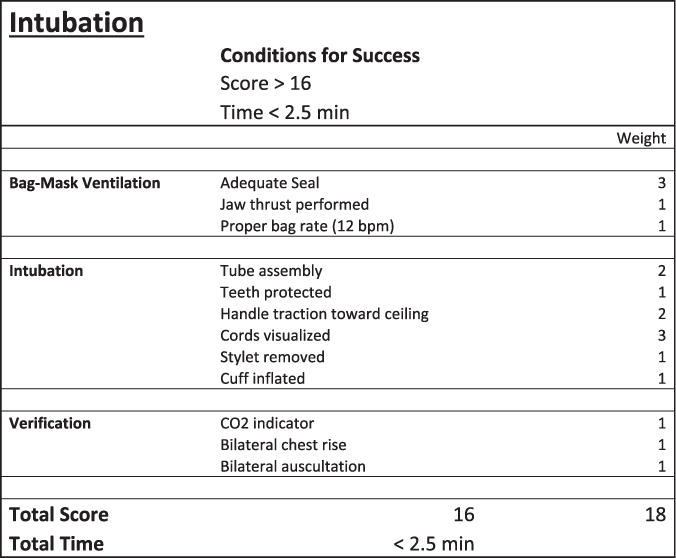

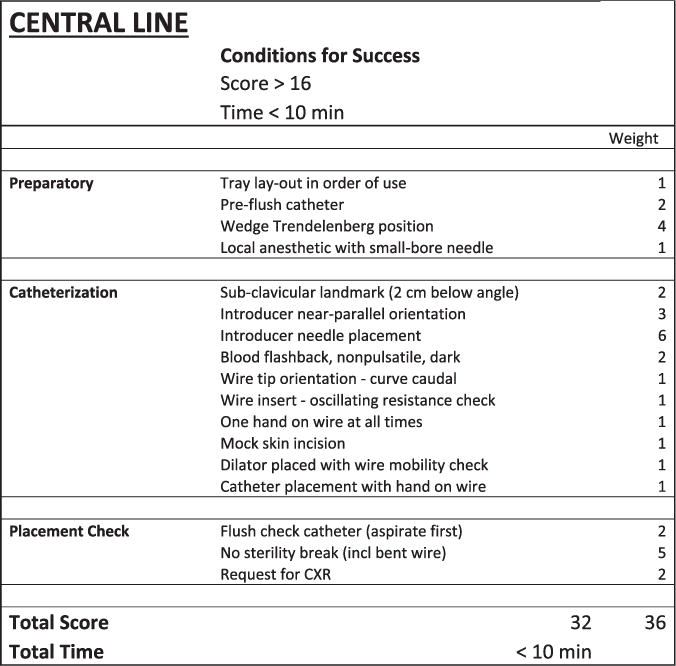

APPENDIX B. PROCEDURAL TASK CHECKLIST

FIGURE B1.

Suturing and knot tying checklist.

FIGURE B2.

Intubation checklist.

FIGURE B3.

CVC checklist.

Footnotes

Meeting presentations: results related to this project were presented at the American College of Surgeons Annual Clinical Congress in San Diego, CA, as an oral presentation in October 2017 and at the Association of Surgical Education Annual Meeting in Boston, MA, as an oral presentation in April 2016.

COMPETENCIES: Practice-Based Learning and Improvement

References

- 1.Shih T, Nicholas LH, Thumma JR, Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB. Does pay-for-performance improve surgical outcomes? An evaluation of phase 2 of the Premier Hospital Quality Incentive Demonstration. Ann Surg. 2014;259(4):677–681. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calderwood MS, Kleinman K, Huang SS, Murphy MV, Yokoe DS, Platt R. Surgical site infections: volume-outcome relationship and year-to-year stability of performance rankings. Med Care. 2017;55(1):79–85. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mattar SG, Alseidi AA, Jones DB, et al. General surgery residency inadequately prepares trainees for fellowship: results of a survey of fellowship program directors. Ann Surg. 2013;258(3):440–449. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182a191ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahmed N, Devitt KS, Keshet I, et al. A systematic review of the effects of resident duty hour restrictions in surgery: impact on resident wellness, training, and patient outcomes. Ann Surg. 2014;259(6):1041–1053. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schaverien MV. Development of expertise in surgical training. J Surg Educ. 2010;67(1):37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cook DA, Brydges R, Zendejas B, Hamstra SJ, Hatala R. Mastery learning for health professionals using technology-enhanced simulation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Med. 2013;88(8):1178–1186. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31829a365d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dietl CA, Russell JC. Effect of process changes in surgical training on quantitative outcomes from surgery residency programs. J Surg Educ. 2016;73(5):807–818. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2016.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu Y, Brooks KD, Kim H, et al. Adaptive simulation training using cumulative sum: a randomized prospective trial. Am J Surg. 2016;211(2):377–383. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loukas C, Nikiteas N, Kanakis M, Moutsatsos A, Leandros E, Georgiou E. A virtual reality simulation curriculum for intravenous cannulation training. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(10):1142–1145. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Leval MR, François K, Bull C, Brawn W, Spiegelhalter D. Analysis of a cluster of surgical failures. Application to a series of neonatal arterial switch operations. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;107(3):914–923. [discussion 923–4] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu Y, Jolissaint JS, Ramirez AG, Gordon R, Yang Z, Sawyer RG. Cumulative sum: a proficiency metric for basic endoscopic training. J Surg Res. 2014;192(1):62–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2014.05.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gershuni V, Woodhouse J, Brunt LM. Retention of suturing and knot-tying skills in senior medical students after proficiency-based training: results of a prospective, randomized trial. Surgery. 2013;154(4):823–829. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.07.016. [discussion 829–30] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu Y, Warren HL, McMurry TL, et al. Cumulative sum: an individualized proficiency metric for laparoscopic fundamentals. J Pediatr Surg. 2016;51(4):598–602. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2015.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu Y, Puri V, Crabtree TD, et al. Attaining proficiency with endobronchial ultrasound-guided trans-bronchial needle aspiration. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;146(6):1387–1392 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.07.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steiner SH, Woodall WH. Debate: what is the best method to monitor surgical performance? BMC Surgery. 2016;16(1):15. doi: 10.1186/s12893-016-0131-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cecilio-Fernandes D, Cnossen F, Jaarsma DADC, Tio RA. Avoiding surgical skill decay: a systematic review on the spacing of training sessions. J Surg Educ. 2018;75(2):471–480. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2017.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doumouras AG, Engels PT. Early crisis nontechnical skill teaching in residency leads to long-term skill retention and improved performance during crises: a prospective, nonrandomized controlled study. Surgery. 2017;162(1):174–181. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2016.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hubert V, Duwat A, Deransy R, Mahjoub Y, Dupont H. Effect of simulation training on compliance with difficult airway management algorithms, technical ability, and skills retention for emergency cricothyrotomy. Anesthesiology. 2014;120(4):999–1008. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brydges R, Carnahan H, Safir O, Dubrowski A. How effective is self-guided learning of clinical technical skills? It′s all about process. Med Educ. 2009;43(6):507–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Madani A, Watanabe Y, Vassiliou MC, et al. Long-term knowledge retention following simulation-based training for electrosurgical safety: 1-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Surg Endosc. 2016;30(3):1156–1163. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4320-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dehmer JJ, Amos KD, Farrell TM, Meyer AA, Newton WP, Meyers MO. Competence and confidence with basic procedural skills: the experience and opinions of fourth-year medical students at a single institution. Acad Med. 2013;88(5):682–687. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31828b0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stefanidis D, Acker C, Heniford BT. Proficiency-based laparoscopic simulator training leads to improved operating room skill that is resistant to decay. Surg Innov. 2008;15(1):69–73. doi: 10.1177/1553350608316683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]