Abstract

Heat stress, an important and damaging abiotic stress, regulates numerous WRKY transcription factors, but their roles in heat stress responses remain largely unexplored. Here, we show that pepper (Capsicum annuum) CaWRKY27 negatively regulates basal thermotolerance mediated by H2O2 signaling. CaWRKY27 expression increased during heat stress and persisted during recovery. CaWRKY27 overexpression impaired basal thermotolerance in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) and Arabidopsis thaliana, CaWRKY27-overexpressing plants had a lower survival rate under heat stress, accompanied by decreased expression of multiple thermotolerance-associated genes. Accordingly, silencing of CaWRKY27 increased basal thermotolerance in pepper plants. Exogenously applied H2O2 induced CaWRKY27 expression, and CaWRKY27 overexpression repressed the scavenging of H2O2 in Arabidopsis, indicating a positive feedback loop between H2O2 accumulation and CaWRKY27 expression. Consistent with this, CaWRKY27 expression was repressed under heat stress in the presence H2O2 scavengers and CaWRKY27 silencing decreased H2O2 accumulation in pepper leaves. These changes may result from changes in levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS)-scavenging enzymes, since the heat stress-challenged CaWRKY27-silenced pepper plants had significantly higher expression of multiple genes encoding ROS-scavenging enzymes, such as CaCAT1, CaAPX1, CaAPX2, CaCSD2, and CaSOD1. Therefore, CaWRKY27 acts as a downstream negative regulator of H2O2-mediated heat stress responses, preventing inappropriate responses during heat stress and recovery.

Keywords: Capsicum annuum, abiotic stress, thermotolerance, CaWRKY27, H2O2

Introduction

High temperatures can damage plants, causing membrane injury, inactivating proteins, increasing production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and damaging key metabolic functions (Quinn, 1988; Iba, 2002; Wahid, 2007). This abiotic stress leads to heavy crop losses, threatens food security, and is of increasing concern due to global climate change. Because of their sessile lifestyles, plants inevitably encounter heat stress (HS) and have evolved defense mechanisms to help them cope with this stress. These mechanisms include perception of HS, initiation and transduction of defense signals, and massive transcriptional reprogramming by various transcription factors (TFs). This transcriptional reprogramming leads to synthesis of heat shock proteins (HSPs) that ameliorate the protein misfolding and aggregation issues caused by HS (Queitsch et al., 2000). A variety of molecules are involved in signaling HS, including Ca2+ (Jia et al., 2014), phytohormones such as salicylic acid (Clarke et al., 2004), jasmonic acid (Clarke et al., 2009), ethylene (Larkindale and Huang, 2004), and abscisic acid (Larkindale and Huang, 2004), and ROS such as H2O2 (Zang et al., 2017; Salvi et al., 2018) and NO (Wang et al., 2014).

Transcription factors play crucial roles in the HS response by responding to upstream defense signals and transcriptionally modulating the expression of thermotolerance-associated genes (Fragkostefanakis et al., 2015; Ohama et al., 2017). For example, HSFA6b plays a role in the HS response by controlling the expression of HSPs in response to abscisic acid signaling (Huang et al., 2016). SPL1 and SPL12 contribute to heat-triggered transcriptional reprogramming (Chao et al., 2017). Upon interacting with phosphatases, the RCF2 and NAC019 transcriptionally regulate the expression of HSFA1b, HSFA6b, HSFA7a, and HSFC1, which encode TFs that transcriptionally regulate the expression of HSPs (Guan et al., 2014). These results demonstrate the important, complex role that TFs play in regulating thermotolerance, however, the roles of TFs in the plant HS response, and how they are connected to the upstream signaling components, has yet to be elucidated.

Reactive oxygen species are produced by NADPH oxidases (termed respiratory burst oxidase homologs, RBOHs) in the apoplast, and by oxidases and peroxidases in the chloroplast, mitochondria, peroxisome, and possibly other cellular compartments (Suzuki et al., 2011; Mignolet-Spruyt et al., 2016). They can also be scavenged by ROS-detoxifying enzymatic proteins such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), ascorbate peroxidase (APX), catalase (CAT), glutathione peroxidase (GPX), and peroxiredoxin (PRX), or by antioxidants such as ascorbic acid and glutathione (Davletova et al., 2005). The synthesis and scavenging of ROS is balanced in healthy plants. However, this balance is frequently upset when plants are challenged by various stressors, resulting in a ROS burst that causes oxidative stress, which includes oxidative damage to membranes, proteins, RNA, and DNA molecules, and potentially the oxidative destruction of the cell (Mittler, 2002). ROS also serve as signal transduction molecules (Choudhury et al., 2017; Salvi et al., 2018). Some TFs such as HsfA1a directly sense H2O2 and modulate the transcription of genes involved in the plant HS response. However, our knowledge of the connection between H2O2 and the various TFs that regulate thermotolerance is very limited.

WRKY TFs are one of the largest TF families in plants and have been implicated as positive or negative regulators of growth, development, and responses to the environment. WRKYs are classified based the presence of one or two highly conserved WRKY domains as well as their specific binding to conserved cognate W-boxes [TTGAC (C/T)]. Significant differences in WRKY gene expression under HS were observed for 30 of the 36 tested WRKYs in radish (Karanja et al., 2017) and 17 of the 22 tested WRKYs enhanced their expression in potato (Zhang et al., 2017), indicating that multiple WRKY TFs participate in the regulation of the plant HS response. Multiple WRKY TFs function in thermotolerance by modulating the expression of heat-inducible and oxidative stress-responsive genes Hsp, Hsf, PR1, and MBF1c (Li et al., 2010, 2011). These characterized WRKY TFs include AtWRKY25 (Li et al., 2009), AtWRKY26, AtWRKY33 (Li et al., 2011), AtWRKY39 (Li et al., 2010), CaWRKY6 (Cai et al., 2015), CaWRKY40 (Dang et al., 2013), TaWRKY1, TaWRKY33 (He et al., 2016), and OsWRKY11 (Wu et al., 2009), which regulate the plant HS response. However, since only a subsets of WRKY TFs that are involved in regulating the HS response have been characterized, the roles of the remaining WRKY TFs remain to be elucidated.

Pepper (Capsicum annuum) is an agriculturally important crop from the Solanaceae. HS not only adversely affects its growth and development, but also increases its susceptibility to disease when grown under high humidity conditions. A better understanding of the mechanism of thermotolerance in pepper has potential applications for the genetic improvement of its heat tolerance. Previously, we showed that CaWRKY6 (Cai et al., 2015), and CaWRKY40 (Dang et al., 2013) act as positive regulators of the HS response in pepper and Ralstonia solanacearum infection (RSI), and that CaWRKY6 regulates the expression of CaWRKY40 in these responses (Cai et al., 2015). CaWRKY27 is induced by RSI as well as exogenously applied salicylic acid, methyl jasmonate, or ethylene, and its overexpression in tobacco conferred resistance to RSI. Virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) of CaWRKY27 in pepper attenuated its resistance to RSI (Dang et al., 2014). In this study, the results from gain-of-function and loss-of-function analyses indicate that CaWRKY27 also acts as a crucial negative regulator of basal thermotolerance in pepper via the H2O2-mediated signaling pathway, and plays a significant role in coordinating disease resistance.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

Seeds from Capsicum annuum #8 (provided by the pepper breeding group of Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University) and tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) cultivar K326 (provided by Tobacco Institute of Fujian Tobacco Company) were soaked in water at 25 ± 2°C°C overnight, and then were sown into a steam-sterilized soil mix (peat moss and vermiculite, 1/1, v/v) in plastic pots. Plants were grown in a growth room that was maintained at 25 ± 2°C with a light intensity of ∼100 μmol photons m−2s−1 and a relative humidity of 70% under a 16-h-light/8-h-dark cycle.

Wild-type (Col-0) and transgenic Arabidopsis seeds were vernalized for 3 days in the dark at 4°C and transferred onto ½-strength MS and 0.8% agar plates that were incubated in a growth chamber (22 ± 2°C, ∼100 μmol photons m−2 s−1, relative humidity 85%, and 16-h light/8-h dark cycle).

Construction of Transgenic Plants

To construct the 35S promoter-driven CaWRKY27-overexpression construct, the coding region of CaWRKY27 was PCR amplified using the primers CaWRKY27-CSDF and CaWRKY27-CDSR, and then cloned into the pK7WG2 vector using the gateway system (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To construct the CaWRKY27 promoter-GUS fusion, fragments upstream of CaWRKY27 were amplified from pepper genomic DNA using PCR and were cloned into the pMDC163 vector (Invitrogen). Each construct was introduced separately into Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101, which was then used to transform Arabidopsis with the floral dip method. Transgenic lines were selected by germinating seeds on 1/2 MS medium containing kanamycin (50 mg/L) or hygromycin (50 mg/L) as required, then selfed, and only lines segregating the transgene in a 3:1 ratio were selected for further analysis. The T3 seeds from CaWRKY27-OE4 and CaWRKY27-OE9 tobacco K326 plants were obtained as described previously (Dang et al., 2013), and then used for phenotypic scoring under HS.

Treatments and Growth Analysis

To investigate CaWRKY27 transcript levels in pepper plants, six-leaf stage pepper plants were treated at 42°C as described previously (Guo et al., 2007; Dang et al., 2013), and pepper leaves were harvested at 0, 0.5, 1, 3, and 6 h, and at 2, 4, 8, and 12 h after recovery at 25°C. For the exogenous H2O2 application, six-leaf stage pepper plants were sprayed with 20 mM H2O2 and plants were collected 0, 1, 3, 6, 12, 24, 36, and 48 h later. To analyze pCaWRKY27::GUS transgenic lines, 7-day-old Arabidopsis seedlings were treated at 37°C for 1 h, H2O2 (10 mM for 2 h). For phenotypic analysis, the CaWRKY27-silenced pepper, Arabidopsis, or tobacco plants were treated with HS at various times and analyzed (detailed methods are described in the figure legends). For qRT-PCR analysis, approximately 50-day-old CaWRKY27-silenced pepper plants, approximately 1-month-old Arabidopsis plants, and 45-day-old tobacco plants were subjected to HS and were harvested at the indicated time points according to the method described in the figure legends. To assay the effect of oxygen species scavengers on H2O2 production during pepper response to HS, the detached pepper leaves were employed and were tiled on 1/2 MS medium with or without 10 mM ascorbic acid, 100 μM DPI and 100 μM quinacrine (Chen et al., 2013; Mellidou et al., 2017). For HS treatment, the treated pepper leaves were put to temperature of 42, 38, 35, or 33°C, it was found that temperature of 42, 38, and 35°C resulted in rapidly leaves death, difficulty in H2O2 detection, and quick RNA degradation. So the treatment under 33°C for 3 h and recover for 1/2 h was finally employed.

Histochemical Staining

H2O2 accumulation was detected with DAB staining. Pepper or Arabidopsis leaves were soaked in 1 mg⋅mL−1 diaminobenzidine (DAB, Sigma) for 15 h, and were cleared by boiling in a 1:1:3 mixture of lactic acid:glycerol:absolute ethanol (V:V:V) followed by destaining overnight in absolute ethanol as described previously (Dang et al., 2013). Representative phenotypes were photographed with a light microscope (Leica, Germany). To detect GUS expression, the samples were immersed into GUS staining solution [1 mg⋅mL−1 X-Gluc, 1 mM K3Fe(CN)6, 1 mM K4Fe(CN)6, 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.0, 10 mM Na2EDTA, 0.1% Triton X-100] and incubated overnight at 37°C. The chlorophyll was then removed with several washes with 75% ethanol and phenotypes were observed and documented with a stereoscope (Leica, Germany).

Electrolyte Leakage Measurements

Electrolyte leakage assays in Arabidopsis (Clarke et al., 2004) and pepper (Kim et al., 2010) were performed as described previously. Briefly, leaf disks 4 cm in diameter were washed in sterile double-distilled water for 30 min with slight agitation for 2 h at 25°C, and electrolyte leakage was detected using a conductivity meter (METTLER TOLEDO, Switzerland).

Virus-Induced Gene Silencing

Tobacco rattle virus (TRV) based VIGS was performed to generate CaWRKY27-silenced pepper plants (PYL-279-wrky27, PYL-279-wrky27-3′utr). Fragments of the CaWRKY27 coding sequence or the CaWRKY27 3′ untranslated region (UTR) were cloned from pepper cDNA and inserted into the PYL-279 vector using gateway cloning (Invitrogen) as described previously (Dang et al., 2013). Fully expanded cotyledons from ∼16-day-old pepper seedlings were co-infiltrated with A. tumefaciens strain GV3101 carrying PYL-192 as well as PYL-279-pds (Dang et al., 2013), PYL-279-wrky27, or PYL-279-wrky27-3′utr. About 20 days later, a photobleaching phenotype was observed due to phytoene desaturase (PDS) silencing in the positive control pepper plants (PYL-279-pds), and the transcript levels of CaWRKY27 were measured in PYL-279-wrky27 and PYL-279-wrky27-3′utr pepper plants by qRT-PCR after exposure to HS.

Gene Expression Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from Arabidopsis, pepper, or tobacco plants by using the TaKaRa MiniBEST Universal RNA Extraction Kit (TaKaRa, Japan). RNA (1 μg) was used to synthesize cDNA with the TaKaRa PrimeScript RT-PCR Kit (TaKaRa, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Transcript levels were measured with a CFX96 real-time PCR instrument (Bio-Rad, United States), the SYBR Premix Ex Taq II reagent (TaKaRa Perfect Real Time), and specific primers (Supplementary Table S1). Arabidopsis UBIQUITIN10 (AtUBQ10), tobacco Elongation factor 1 alpha (NtEF1α), and pepper Actin1 (CaActin1) were used for normalization.

Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed using three biological triplicates. All the data are expressed as the mean ± SE. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used on the data sets and tested for significant (P < 0.05 and P < 0.01) treatment differences using Student–Newman–Keuls test.

Results

CaWRKY27 Expression Was Induced in Pepper Plants During Heat Stress and During the Recovery From Heat Stress

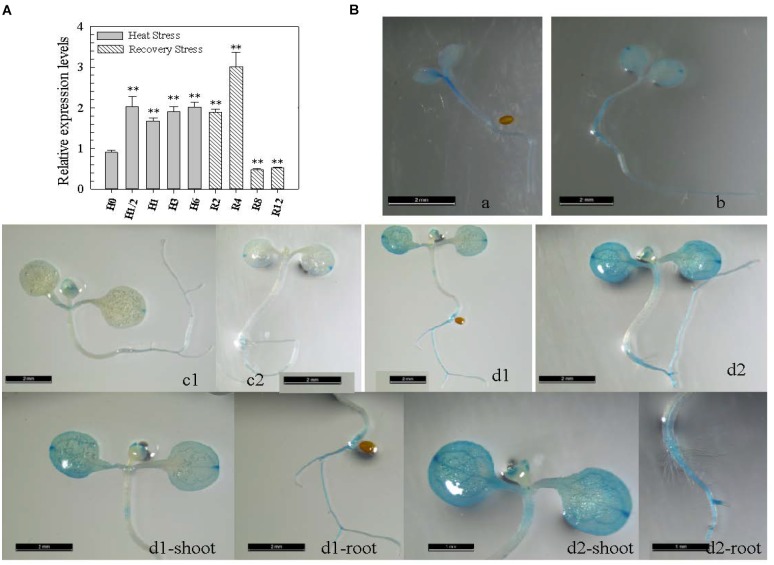

The presence of four HS elements (HSEs) in the CaWRKY27 promoter region implies that it may be involved in the HS response (Supplementary Figure S1A); however, a role for CaWRKY27 in pepper thermotolerance had not been reported. To test this speculation, we measured the transcript level of CaWRKY27 in pepper leaves by qRT-PCR at different time points during or after treatment with HS. We found that the transcript abundance of CaWRKY27 increased after 0.5 to 6 h at 42°C and that this increase persisted for an additional 4 h of recovery at room temperature (25°C). The maximum transcript abundance increase was approximately 3.0-fold compared to control plants and was observed after 4 h of recovery at room temperature (Figure 1A).

FIGURE 1.

CaWRKY27 was transcriptionally induced by heat treatment in pepper plants. (A) CaWRKY27 expression in pepper leaves was determined with qRT-PCR at the indicated time points during or after heat treatment. Relative transcript levels of CaWRKY27 in heat-treated pepper plants were compared to the control, which was set to a relative expression level of ‘1.’ Data represent the mean ± SE of three biological replicates, and asterisks indicate significant difference compared to control plants (SNK-test, ∗P < 0.05 or ∗∗P < 0.01). H, heat; R, recovery. (B) GUS expression in transgenic Arabidopsis plants carrying the pCaWRKY27::GUS construct. Figures a, b, c1, and c2, show a seedling of 3 (a), 5 (b) and 7 (c1 and c2) days after germination (DAG). In figures d1 and d2 transgenic pCaWRKY27::GUS seedlings were heat treated. In figures d1-shoot, d1-root, d2-shoot, and d2-root the shoot or root was magnified from the corresponding d1 or d2 figures, respectively. These seedlings or plants were grown on ½ MS media under 16 h light/8 h dark conditions.

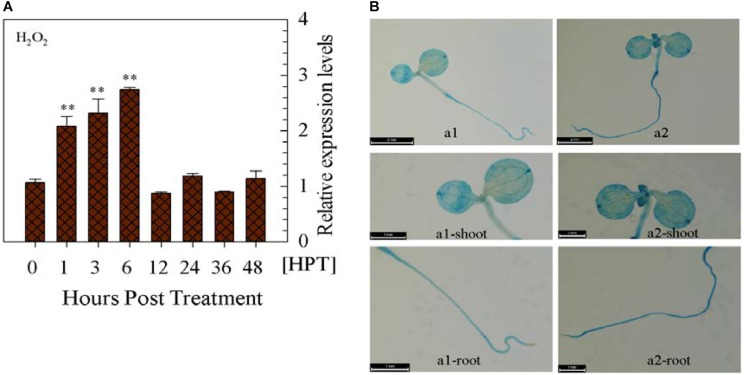

To confirm the increase in CaWRKY27 expression upon exposure to HS, we examined CaWRKY27 expression using a promoter-GUS fusion. To this end, we produced transgenic A. thaliana lines carrying the 2-kb region genomic region upstream of the CaWRKY27 translational start codon fused to a GUS reporter gene. Ten independent homozygous single-copy CaWRKY27 promoter-GUS fusion lines were examined, and representative consensus expression patterns were described (Figure 1B). GUS expression in leaves and roots was extremely low in 7-day-old transgenic Arabidopsis seedlings that were not challenged by stress, and enhanced when plants were challenged with HS at 37°C for 1 h. Together, these results suggest that CaWRKY27 might play a role in pepper thermotolerance. The high consistency between the results from qRT-PCR and GUS expression experiments indicate that the induction of CaWRKY27 by HS.

Silencing of CaWRKY27 Enhanced the Tolerance of Pepper Plants to Heat Stress

The induction of CaWRKY27 expression by HS in pepper plants suggests that CaWRK27 may be involved in the HS response. To test this, we performed a knockdown experiment in which CaWRKY27 gene expression was silenced by VIGS in pepper seedlings, followed by analysis of the physiological and molecular responses of the CaWRKY27-silenced pepper plants to HS. We used two constructs that targeted different regions of the CaWRKY27 transcript, PYL-279-wrky27, which targets the open reading frame, and PYL-279-wrky27-3′utr, which targets the 3′ UTR. The efficiency of CaWRKY27 silencing by VIGS was confirmed by qRT-PCR, which showed that the CaWRK27 transcript level decreased by approximately 3.51-fold and 3.32-fold in the pepper plants inoculated with PYL-279-wrky27 and PYL-279-wrky27-3′utr, respectively, compared to control plants inoculated with empty vector (PYL-279) under normal conditions and by or 3.56-fold and or 3.61-fold under HS (Supplementary Figure S1B).

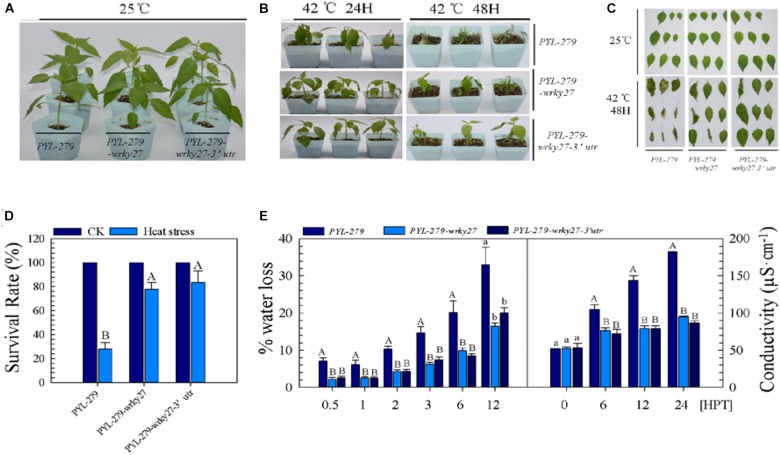

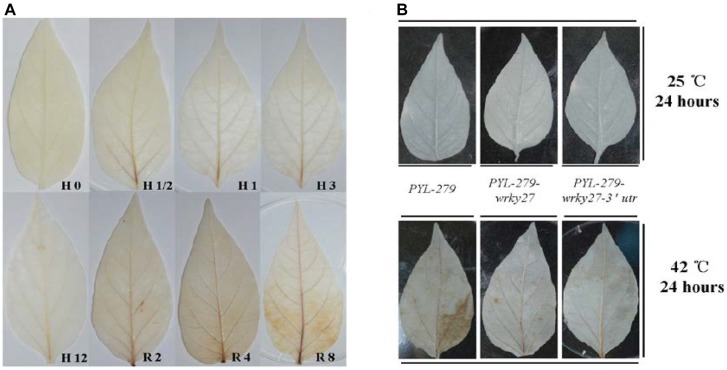

We further examined the effect of CaWRKY27 silencing on thermotolerance in pepper by investigating phenotypic changes in PYL-279, PYL-279-wrky27, and PYL-279-wrky27-3′utr plants in response to HS. No phenotypic differences were observed under normal condition (Figure 2A). However, when plants were challenged with HS (42°C) for 24 h and then returned to room temperature (25°C) to recover for 3 days, PYL-279 plants exhibited a moderate wilted phenotype, while only slightly wilted phenotypes were observed in PYL-279-wrky27 and PYL-279-wrky27-3′utr plants (Figure 2B). When the plants were challenged with HS (42°C) for 48 h and then returned to room temperature to recover for 3 days, PYL-279 plants had a lower survival rate (27%) compared with PYL-279-wrky27 (77%) and PYL-279-wrky27-3′utr (83%) plants (Figures 2B–D). Additionally, we found that the fresh weight loss of leaves due to HS-induced water loss was lower in PYL-279-wrky27 and PYL-279-wrky27-3′utr plants than that in PYL-279 plants. This was accompanied by significantly less electrolyte leakage in the leaves of PYL-279-wrky27 and PYL-279-wrky27-3′utr plants than in the leaves of PYL-279 plants when challenged with HS (Figure 2E). Together, these data suggest that CaWRKY27 silencing enhanced the basal thermotolerance of pepper plants and that CaWRKY27 might act as a negative regulator of basal thermotolerance in pepper.

FIGURE 2.

CaWRKY27 silencing enhanced basal thermotolerance in pepper plants. (A) PYL-279, PYL-279-wrky27, and PYL-279-wrky27-3’utr pepper plants that were grown in pots for 6 weeks under normal conditions. (B) Phenotypes of PYL-279, PYL-279-wrky27, and PYL-279-wrky27-3’utr pepper plants after 3 days recovery following heat treatment at 42°C for 24 or 48 h. (C) Digital photographs of isolated leaves from the corresponding plants. (D) Survival rate were analyzed in PYL-279, PYL-279-wrky27, and PYL-279-wrky27-3’utr plant after 3 days recovery following heat treatment at 42°C for 48 h. Data represent the mean ± SE (n = 3), each replicate consists of six plants. (E) Percentage of water loss and ion leakage (conductivity) were detected in PYL-279, PYL-279-wrky27, and PYL-279-wrky27-3’utr leaves. Data represent the mean ± SE of three biological replicates. Different letters indicate significant differences compared to PYL-279 plant leaves (SNK-test, lowercase letters indicate P < 0.05, and uppercase letters indicate P < 0.01).

Overexpression of CaWRKY27 Reduced Thermotolerance in Tobacco and Arabidopsis

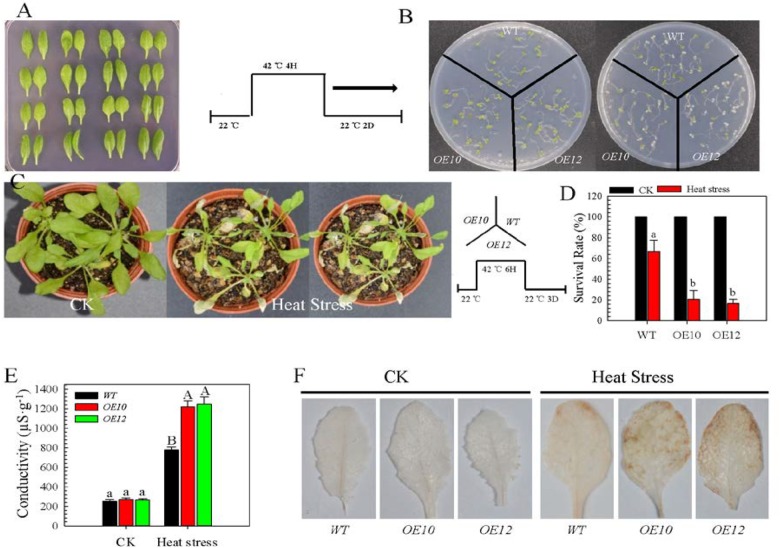

To confirm a role of CaWRKY27 in thermotolerance, we generated transgenic Arabidopsis that overexpression of CaWRKY27 driven by the CaMV 35S promoter and obtained 14 homozygous T4 lines. Semi-quantitative PCR shows that the transcript levels of CaWRKY27 were similar among all 14 T4 lines (Supplementary Figure S1C), although we did not observe any morphological differences between the T4 CaWRKY27-OE lines and wild-type (WT) plants (Figure 3A). Two independent T4 homozygous single-copy lines (CaWRKY27-OE10 and OE12) that had moderate levels of CaWRKY27 expression were used in further analyses. When CaWRKY27-OE10 and OE12 seedlings were grown on ½-strength Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium for 5 days, there was no significant morphological difference compared with the WT under normal conditions. However, upon HS (37°C) for 4 h followed by a 2 days recovery at 22°C, CaWRKY27-OE10 and OE12 displayed a decrease in thermotolerance compared to the WT (Figure 3B).

FIGURE 3.

Overexpression of CaWRKY27 reduced basal thermotolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis plants. (A) Leaves of CaWRKY27-overexpressing Arabidopsis and WT plants that were grown in pots for 5 weeks under normal conditions. (B) Phenotypes of CaWRKY27-OE10, OE12, and WT seedling that were treated at 37°C for 4 h and then returned to 22°C for 2 days of recovery. (C) Phenotypes of 35-day-old CaWRKY27-OE10, OE12, and WT plants that were treated at 37°C for 6 h and then returned to 22°C for 3 days of recovery. (D) Survival rate were analyzed in CaWRKY27-OE10, OE12, and WT plant after 3 days recovery following heat treatment at 37°C for 6 h. Data represent the mean ± SE (n = 3), each replicate consists of eight plants. (E) Electrolyte leakage in 28-day-old heat-treated seedlings was monitored by measuring conductivity. (F) H2O2 accumulation in leaves from heat-treated (37°C) WT, CaWRKY27-OE10, and OE12 plants was measured by DAB staining. Data represent the mean ± SE of three biological replicates. Different letters indicate significant differences compared to WT (SNK-test, lowercase letters indicate P < 0.05, and uppercase letters indicate P < 0.01).

To directly assess the effect of CaWRKY27 overexpression on HS tolerance, we subjected 3-week-old CaWRKY27-OE10, OE12 and WT plants to 37°C for 6 h followed by a 3 days recovery at 22°C in a growth chamber. We observed that the WT plants grew much better under this condition (Figure 3C) and had higher survival rates (67%) compared to the CaWRKY27-OE10 (20%) and OE12 (16%) lines (Figure 3D). Accordingly, remarkably high electrolyte leakages were detected in CaWRKY27-OE10 and OE12 plants compared to the WT upon HS (Figure 3E). In addition, more H2O2 accumulation was detected in CaWRKY27-OE10 and OE12 plants than in WT plants under HS (Figure 3F).

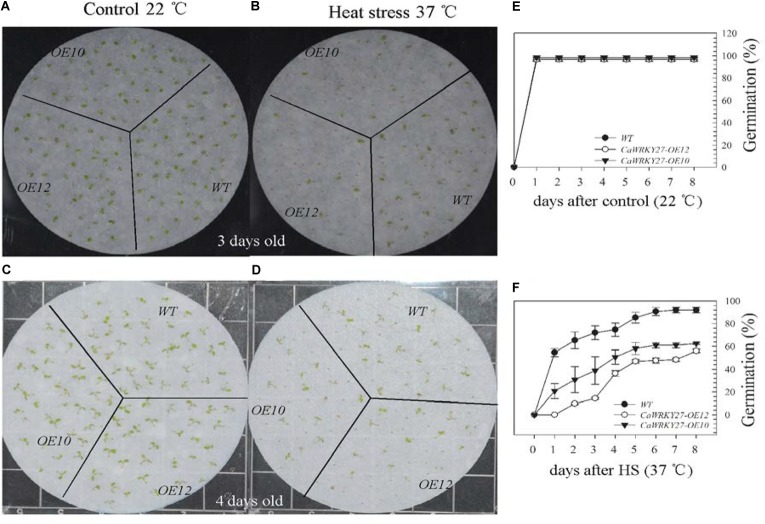

We also examined the seed germination of WT, CaWRKY27-OE10, and OE12 under HS (37°C) after vernalization for 3 days at 4°C, and scored the percentages of radicle emergence daily until no further germination was observed. Two days after HS treatment, lower seed germination ratios were observed for CaWRKY27-OE10 (38%) and OE12 (14%) compared to the WT (72%), while 6 days after HS treatment, the seed germination ratios were 61% and 47% for CaWRKY27-OE10 and OE12, respectively, and 90% for WT plants (Figures 4B,D,F). By contrast, no significant differences in seed germination were observed among WT, CaWRKY27-OE10, and OE12 lines at room temperature (Figures 4A,C,E).

FIGURE 4.

Responses of WT and CaWRKY27-overexpressing Arabidopsis lines to heat treatment during seed germination. (A–D) Illustration of representative seeds or seedlings at 3 or 4 days after heat treatment. (E,F) The percent of radicle emergence was recorded daily until no further radicles emerged in seeds of WT, CaWRKY27-OE10, and OE12 plants. Seeds were treated at 37°C or at 22°C for the control. Data represent the mean ± SE (n = 3), each replicate consists of 30 seeds.

In parallel, we generated nine CaWRKY27-overexpressing T2 transgenic tobacco lines and assessed CaWRKY27 transcript levels with qRT-PCR (Supplementary Figure S2A). Two independent lines (OE4 and OE9) with high CaWRKY27 expression levels were selected and used to generate T3 lines that were then used in phenotypic analyses. We first examined the survival rate of 15-day-old CaWRKY27-OE4, OE9, and WT seedlings that had been treated at 42°C for 48 h followed by a 2 days recovery at 25°C. After this treatment, the survival rates of CaWRKY27-OE4 and OE9 seedlings were much lower than the WT seedlings (Supplementary Figure S2B). Second, traits related to thermosensitivity were assessed in 1-month-old CaWRKY27-OE4, OE9, and WT plants that were treated at 42°C for 48 h followed by a 48-h recovery at 25°C. HS-induced necrosis was clearly visible on CaWRKY27-OE4 and OE9 plants, while only minor necrosis was observed on WT plants (Supplementary Figure S2C). The same HS treatment and recovery was performed with 50-day-old WT, CaWRKY27-OE4, and OE9 plants, the survival rates of CaWRKY27-OE4 and OE9 seedlings were much lower than the WT seedlings (Supplementary Figure S2D). We also tested the seed germination of CaWRKY27-OE4, OE9, and WT seeds by exposing them to 42°C for 15 h, and then returning them to 25°C to germinate. No significant difference in the percent seed germination was observed between CaWRKY27-OE4, OE9, and WT seeds at 25°C; however, significant differences were observed between CaWRKY27-OE4 and OE9 plants (26% and 25%, respectively) compared with WT plants (72%) at 8 days after treatment (DAT), as well as at 10 DAT (59% and 58% for CaWRKY27-OE4 and OE9, respectively, and 81% for WT seeds) (Supplementary Figure S2E).

The Expression of Heat Stress Defense Genes Is Induced in Plants Overexpressing CaWRKY27

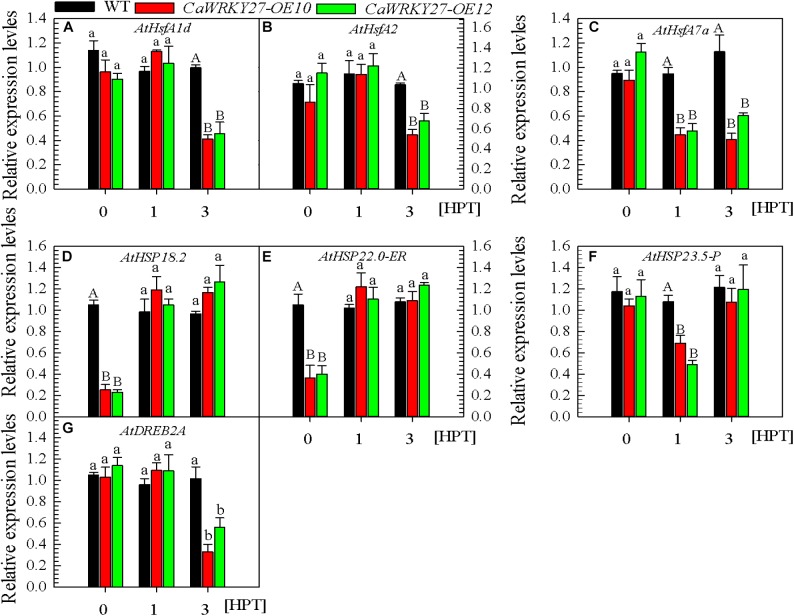

To confirm the indicated role for CaWRKY27 as a negative regulator of thermotolerance and test its possible mode of action, we examined the effect of CaWRKY27 overexpression on the transcript abundance of HS-response marker genes in transgenic tobacco and Arabidopsis under HS. We measured the ROS detoxification-associated genes NtGST1 and NtCAT1 (Takahashi et al., 1997), the ethylene biosynthesis-associated genes NtACC deaminase, NtACS1, NtACS6, NtEFE26, and NtACC Oxidase (Chen et al., 2003), and the thermotolerance-associated genes NtHSF2, NtHSP18, and NtHSP90. Our results showed that, in plants treated at 42°C, transcript levels of these genes were lower at 24 and 48 h post treatment (hpt) in transgenic tobacco than in WT (Supplementary Figure S3). The transcript levels of thermotolerance-associated genes, including the TF genes AtHsfA1d, AtHsfA2 (Nishizawa-Yokoi et al., 2011), AtHsfA7a, and AtDREB2A (Sakuma et al., 2006), and the chaperone genes AtHSP18.2, AtHSP22.0-ER, and AtHSP23.5-P (Kotak et al., 2007; Ohama et al., 2016) were also measured by qRT-PCR in HS challenged or unchallenged plants. AtHSP18.2 and AtHSP22.0-ER (Figures 5D,E) transcript abundances were significantly lower in CaWRKY27-OE lines under normal conditions compared with the WT. However, AtHsfA1d, AtHsfA2, AtHsfA7a, AtDREB2A, and AtHSP23.5-P (Figures 5A–C,F,G) did not exhibit any difference in their transcript abundances compared to that in the WT plants. No significant differences were observed in the transcript abundance of AtHsfA1d, AtHsfA2, and AtDREB2A between WT and CaWRKY27-OE plants at 1 hpt, yet the transcript abundance of these genes, as well as AtHsfA7a (Figure 5C), decreased significantly in CaWRKY27-OE lines at 3 hpt, compared with WT plants. Additionally, the expression of AtHSP23.5-P was significantly repressed in CaWRKY27-OE lines at 1 hpt, compared to WT plants (Figure 5F). Together, these data indicate that the overexpression of CaWRKY27 negatively regulated basal thermotolerance in Arabidopsis plants by modulating the expression of HS response marker genes.

FIGURE 5.

Analysis of thermotolerance-responsive gene expression levels by qRT-PCR in CaWRKY27-OE10, OE12, and WT plants at 1 and 3 h post treatment with heat stress. (A–C) The relative transcript levels of heat stress response genes AtHsfA1d, AtHsfA2, and AtHsfA7a. (D–F) The relative transcript levels of HSP genes AtHSP18.2, AtHSP22.0-ER and AtHSP23.5-P. (G) The relative transcript levels of transcription factor AtDREB2A. The transcript levels of different gene were normalized against AtUBQ10, followed with normalization against the gene in WT at 0 hpt. Data represent the mean ± SE of three biological replicates. Different letters indicate significant difference compared to WT (SNK-test, lowercase difference P < 0.05 or uppercase difference P < 0.01).

H2O2 Accumulated in the Heat Stress Recovery Stage in Pepper

H2O2 is the most stable ROS and acts as a signaling molecule in plant defense responses, including the pathogen response and HS response (Mittler, 2002; Mittler et al., 2004). We speculated that H2O2 might act as a signaling molecule upstream of CaWRKY27, since CaWRKY27 regulates both pepper immunity against R. solanacearum (Dang et al., 2014) and thermotolerance. To test this hypothesis, we measured H2O2 accumulation and CaWRKY27 transcript abundance in pepper plants during heat treatment, or during their recovery at room temperature. No significant increase in the abundance of H2O2 was observed by diaminobenzidine (DAB) staining at 0.5 to 12 hpt (37°C) in pepper leaves, but a significant increase in the abundance of H2O2 was observed after 2, 4, and 8 h recovery at 25°C in pepper leaves (Figure 6A). DAB staining also detected significant H2O2 accumulation in WT pepper leaves (PYL-279) that were challenged with 42°C for 24 h (Figure 6B), but not in WT and CaWRKY27-VIGS pepper leaves at 25°C. This shows that that H2O2 accumulation was triggered by high temperatures and its presence persisted into the recovery phase in pepper plants.

FIGURE 6.

H2O2 accumulated in response to heat treatment. (A) Accumulation of H2O2 was detected in pepper leaves by DAB staining after 0, 0.5, 1, 3, and 12 h at 37°C and after 2, 4, and 8 h of recovery at 25°C. (B) The accumulation of H2O2 detected by DAB staining after 0 and 24 h of heat treatment in PYL-279, PYL-279-wrky27, and PYL-279-wrky27-3’utr pepper leaves.

Upon the exogenous application of H2O2, CaWRKY27 expression gradually increased over time from 1 to 6 hpt (Figure 7A). To further confirm this result, the expression of GUS driven by pCaWRKY27 was enhanced at 3 h post treatment with exogenous H2O2 (Figure 7B). On contrast, CaWRKY27 expression was significantly repressed in pepper isolated leaves when HS-induced ROS accumulation was cleared after 30 min recovery following heat treatment at 33°C for 3 h via 10 mM AsA, 100 μM DPI and 100 μM quinacrine (Supplementary Figures S4A,B). All these data indicate that CaWRKY27 might act downstream of H2O2 in pepper HSR.

FIGURE 7.

CaWRKY27 gene expression was induced by exogenously applied H2O2 in pepper plants. (A) CaWRKY27 expression in the leaves of WT pepper plants treated with H2O2 as determined by qRT-PCR. Relative CaWRKY27 expression levels were compared between H2O2-treated pepper plants and mock-treated control plants, which were set to a relative expression level of ‘1.’ Data represent the mean ± SE of three biological replicates, and asterisks indicate significant differences compared to control plants (SNK-test, ∗P < 0.05 or ∗∗P < 0.01). HPT, hours post treatment. (B) Seedlings carrying the pCaWRKY27::GUS construct were treated with H2O2 (10 mM) for 3 h. The a1-shoot, a1-root, a2-shoot, and a2-root, photographs are magnified images of the shoot or root of the corresponding a1 or a2 seedlings.

Expression of ROS-Scavenging Enzymes and H2O2 Accumulation Were Affected by CaWRKY27 Silencing in Pepper Plants

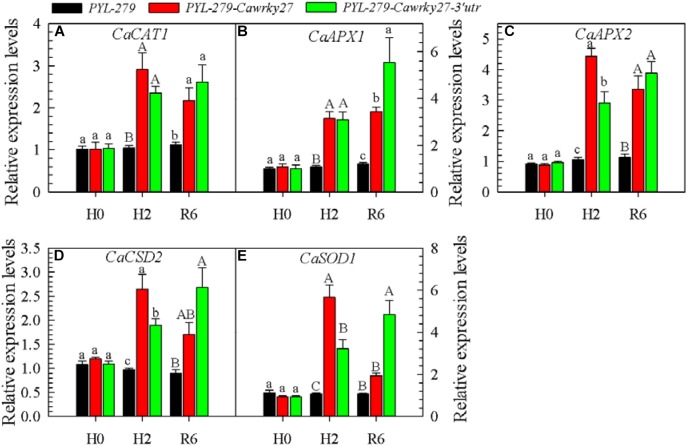

To further confirm the relationship between CaWRKY27 and ROS accumulation, we investigated the expression of ROS-scavenging enzymes, including CaCAT1, CaAPX1, CaAPX2, CaCSD2, and CaSOD1, in CaWRKY27-silenced pepper plants. The results show that the expression levels of CaCAT1, CaAPX1, CaAPX2, CaCSD2 and CaSOD1 (Figures 8A–E) were significantly higher in CaWRKY27-silenced pepper plants than that in the WT exposed to 37°C for 2 h, and also at 6 hpt. No significant differences in the expression of these genes were detected under normal growth conditions (Figure 8). In accordance with this finding, H2O2 accumulation was significantly higher in the control plant (PYL-279) leaves than that in the CaWRKY27-silenced pepper leaves when the plants were challenged with 42°C for 24 h. This suggests that CaWRKY27 silencing induces the expression of ROS-scavenging enzyme genes that in turn reduces the accumulation of ROS, including H2O2.

FIGURE 8.

Analysis of defense-associated gene expression in CaWRKY27-silenced plants. The silenced (PYL-279-wrky27 and PYL-279-wrky27-3’utr) and control (PYL-279) pepper plant leaves were harvested after 0 and 2 h at 37°C, and after 6 h of recovery at 25°C (after 2 h of heat treatment). (A–E) Relative transcript levels of genes encoding the ROS-scavenging enzymes CaCAT1, (A); CaAPX1, (B); CaAPX2, (C); CaCSD2, (D); and CaSOD1, (E). The transcript level of each gene was determined by qRT-PCR and normalized against CaActin, followed by normalization against the transcript level of the gene in PYL-279. Data represent the mean ± SE of three biological replicates. Different letters indicate significant differences compared to the control (SNK-test, lowercase letters indicate P < 0.05 and uppercase letters indicate P < 0.01).

Discussion

The HS caused by global climate change adversely affects plant growth and development, damaging crop yields and threatening food security. Transcriptome analyses identified a subset of WRKY TFs that were transcriptionally modulated in response to HS (Karanja et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2017), implying that they might participate in the regulation of the plant HS response. However, information on the roles of WRKY TFs in regulating plant thermotolerance remains limited. We have previously shown that CaWRKY27 acts as a positive regulator of the pepper response to RSI (Dang et al., 2014); in the present study we provide new evidence that CaWRKY27 also acts as a negative regulator of basal thermotolerance in pepper, and that this regulation is mediated by H2O2 signaling.

Our qRT-PCR and GUS-promoter fusion analysis showed that CaWRKY27 expression was induced by HS in Arabidopsis, suggesting that CaWRKY27 might be involved in the HS response in pepper. This was further confirmed by VIGS-mediated silencing of CaWRKY27 expression in pepper and ectopic overexpression of CaWRKY27 in tobacco and Arabidopsis. The CaWRKY27-silenced pepper plants exhibited enhanced thermotolerance that manifested as reduced leaf wilting, water loss, and ion leakage, compared with the control plants. By contrast, the Arabidopsis plants overexpressing CaWRKY27 exhibited decreased thermotolerance, as shown by their lower survival rates and seed germination ratio, as well as higher leaf ion leakage compared to the control plants. Similar phenotypes were also observed in tobacco plants that overexpress CaWRKY27. These results were further supported by our assessment of the expression of thermotolerance-associated genes, including AtHsfA1d (Nishizawa-Yokoi et al., 2011), AtHsfA2 (Nover et al., 1996), AtHsfA7a (Larkindale and Vierling, 2008), AtHSP18.2 (Liu et al., 2005), AtHSP22.0-ER (Wang et al., 2016), AtHSP23.5-P (Kirschner et al., 2000), and AtDREB2A (Reis et al., 2014) in CaWRKY27-overexpressing Arabidopsis plants. All of these genes displayed a decrease in expression during at least one tested time point during or after HS treatment compared to the control plants. Accordingly, thermotolerance-associated genes, including NtHSP18 (Park et al., 2015), NtHSP90 (Rizhsky et al., 2002), and NtHSF2 (Shoji et al., 2000), decreased in expression in the CaWRKY27-overexpressing tobacco plants under heat treatment compared to WT plants.

Since the plant defense response to various stresses is generally resource intensive, activated at the expense of other biological processes, or highly deleterious to the host, defense responses need be tightly regulated to prevent inappropriate stress responses during stress, depress unnecessary defense in the absence of stress, or to inhibit the response after the stress has passed. Therefore, plants require both positive and negative regulators of their stress responses. Since CaWRKY27 was induced during HS and remained elevated throughout the recovery from HS, CaWRKY27 might act as a negative regulator of HS responses in pepper to block inappropriate HS responses, and importantly, to block these responses in pepper plants during their recovery from HS at room temperature. Similarly, a NAC TF (SlJA2) from tomato was also found to act as a negative regulator of basal thermotolerance (Liu et al., 2017).

Extensive crosstalk has been identified within or between plant responses to biotic and abiotic stresses and is believed to provide great regulatory potential that coordinates the various responses to different stresses (Fujita et al., 2006). Multiple studies suggest that a single WRKY TF might be involved in regulating several seemingly disparate processes (Rushton et al., 2010; Dang et al., 2013; Cai et al., 2015). The results from our present and previous studies show that CaWRKY27 is upregulated by RSI and acts as a positive regulator of resistance to RSI in pepper (Dang et al., 2014). This suggests that CaWRKY27 plays a role in the crosstalk between the pathogen and HS responses in pepper. So far, WRKY TFs from various plant species such as CaWRKY6 (Cai et al., 2015), CaWRKY40 (Dang et al., 2013), and AtWRKY33 (Zheng et al., 2006; Li et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2015) have been found to act as a positive regulators of both plant immunity and thermotolerance. Unlike these WRKY TFs, CaWRKY27 acts as a negative regulator of thermotolerance, but as a positive regulator of immunity against R. solanacearum in pepper. CaWRKY27 upregulation upon pathogen attack might enable pepper to activate the immune response against infection by the pathogen, and to recruit more resources for immunity by blocking unnecessary HS responses.

In plants, ROS have been implicated as crucial signaling components in the crosstalk between the biotic and abiotic stress responses (Fujita et al., 2006). H2O2 is the most stable ROS and acts as a signaling molecule in defense responses, including responses to pathogens (Levine et al., 1994; Alvarez et al., 1998; Morales et al., 2016) and abiotic stresses such as heat (Dat et al., 1998). Accordingly, we observed significant H2O2 accumulation in WT pepper leaves at 42°C for 24 h, but no H2O2 accumulation was detected in WT pepper leaves or CaWRKY27-VIGS pepper plants under non-stressed conditions. However, HS rapidly enhanced intracellular production of H2O2, approximately 2.3-fold at 37°C and 2.5-fold at 42°C within a 1-h treatment in Arabidopsis, suggesting different HS response mechanisms between pepper and Arabidopsis. This difference may be due to the heightened temperature sensitivity in Arabidopsis, evident by its inability to survive prolonged HS, a trait that may be due to local adaptation of the genus (Volkov et al., 2006).

The data in the present study established a close relationship between the transcriptional expression of CaWRKY27 with ROS accumulation during pepper’s HS response. ROS accumulation and transcriptional expression of CaWRKY27 triggered by HS were significantly blocked by application of inhibitors of NADPH-oxidase, PA-Oxidase or ascorbic acid at 30 min of recover from HS, since NADPH-oxidase and PA-Oxidase are responsible for ROS accumulation during plant response to biotic or abiotic stress (Moller, 2001; Yoda et al., 2006; Andronis et al., 2014; Ben Rejeb et al., 2015; Karkonen and Kuchitsu, 2015; Gemes et al., 2016), and ascorbic acid is a ROS scavenger, it can be speculated that that both the ROS accumulation and transcription of CaWRKY27 were conferred by ROS production or the inhibition of ROS degradation. More importantly, exogenous application of H2O2 significantly triggered the transcription of CaWRKY27. All these results placed H2O2 upstream CaWRKY27 as a signaling components during pepper response to HS. Similarly, HsfA1a has been found to be regulated by H2O2 that accumulates in response to various stresses (Zhou et al., 2018). Given the existence of multiple HS sensors in plant cells (Mittler et al., 2012; Srivastava et al., 2014), the multiple H2O2 biosynthesis sites [apoplast and chloroplasts, mitochondria and peroxisome (Pellinen et al., 1999; Ozgur et al., 2015; Saxena et al., 2016)] and close relationship between H2O2 accumulation and Ca2+ signaling cascades (Larkindale and Huang, 2004; Qiao et al., 2015), phytohormones [SA, JA, ET, and ABA (Larkindale and Huang, 2004; Oh et al., 2005)] or MAPK cascade (Song et al., 2015), the transduction of H2O2 mediated HS signaling into the nuclei might be performed via complicated signaling networks. In addition, it is also possible that H2O2 might modulate TFs through direct oxidation, since it was recently found that the oxidation of BRASSINAZOLE-RESISTANT1 (BZR1) TF can be induced via H2O2, and played a major role in regulating gene expression (Tian et al., 2018). To elucidate the complicated molecular link between H2O2 accumulation and CaWRKY27 transcription, further investigation is required.

Interestingly, leaves from CaWRKY27-overexpressing Arabidopsis plants exhibited more H2O2 accumulation than control plants, and no significant H2O2 accumulation was observed CaWRKY27-silenced pepper leaves under HS, reflecting a difference in H2O2 accumulation between the response of Arabidopsis and pepper to heat, which might be due to their evolution under different ecological conditions. The positive feedback regulation of H2O2 by CaWRKY27 in pepper plants might be due to the CaWRK27-dependent derepression of ROS-scavenging enzyme genes, including CaCAT1, CaAPX1, CaAPX2, CaCSD2, and CaSOD1. Derepression was evident since the transcript levels of these genes were significantly lower in heat-challenged CaWRKY27-silenced pepper plants than in control plants. This result is consistent with our previous study that found a higher level of H2O2 accumulation in CaWRKY27-overexpressing tobacco plants challenged with RSI (Dang et al., 2014). Similarly, overexpression of tomato SlJA2, a negative regulator of the HS response, in tobacco also represses expression of ROS-scavenging genes (Liu et al., 2017). The positive feedback between H2O2 accumulation and CaWRKY27 expression further supports the speculation that H2O2 might act as a signaling component upstream of CaWRKY27.

Some of the thermotolerance-associated marker genes such as AtHsfA1d, AtHsfA2, AtHsfA7a, AtDREB2A, and AtHSP23.5-P exhibited different expression in unchallenged and heat-treated plants at 1 and 3 hpt. More interestingly, CaCAT1, which was activated by overexpression of CaWRKY27 in transgenic tobacco plants that were inoculated with R. solanacearum (Dang et al., 2014), was downregulated by overexpression of CaWRKY27 in heat-treated transgenic tobacco plants in the present study. One possible explanation for these contradictory results might be that CaWRKY27 function may be modulated by protein–protein interactions that are governed by other signaling inputs that are activated by different stresses. In support of this, some WRKY TFs were found to be functionally modulated by physically interacting with a wide range of proteins with roles in signaling, transcription, and chromatin remodeling (Chi et al., 2013; Alves et al., 2014; Tripathi et al., 2015). Further isolation and functional characterization of potential protein interactors of CaWRKY27 in pepper plants challenged with various stimuli will provide insight into the role of CaWRKY27 in various stress responses.

Collectively, the data in the present study, together with those of our previous study, suggest that CaWRKY27 is a positive regulator of the RSI response and a negative regulator of the HS response in pepper. CaWRKY27-dependent regulation of the HS response is mediated by H2O2-associated signaling, and blocks unnecessary responses during the RSI response, during recovery from HS, and prevents an inappropriate response during HS challenge in pepper.

Author Contributions

SH and YW designed the experiments. FD and JL performed most of experiments and analyzed the data. The other authors assisted in experiments and discussed the results. FD and SH wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31372061 and 31572136).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2018.01633/full#supplementary-material

CaWRKY27 promoter motifs and expression in silenced and overexpression lines. (A) Nucleotide sequences from the CaWRKY27 5’ flanking promoter region. The four heat stress response elements (HSEs) that may act as cis/trans motifs are marked by arrows. (B) Relative expression of CaWRKY27 in PYL-279, PYL-279-wrky27, and PYL-279-wrky27-3’utr pepper plants that had been either unchallenged or challenged with heat stress. CaWRKY27 relative expression was normalized against CaActin, followed by normalization against the CaWRKY27 expression in the PYL-279 control. Data represent the mean ± SE of three biological replicates. (C) Transcription of CaWRKY27 in CaWRKY27-overexpressing Arabidopsis plant lines was determined via semi-quantitative PCR, and normalized against AtUBQ10 expression.

Phenotypes of CaWRKY27-overexpressing tobacco lines. (A) Relative expression of CaWRKY27 was analyzed in nine CaWRKY27-overexpressing lines and WT (K326) plants with qRT-PCR. CaWRKY27 expression was normalized against NtEF1α, followed by normalization against the CaWRKY27 expression in the WT. Data represent the mean ± SE of three biological replicates. (B–D) Phenotypes of 15-, 30-, and 55-day-old CaWRKY27-overexpressing lines and WT plants that were treated at 42°C for 48 h, then returned to 25°C to recover for 48 h. (E) Effect of heat on seed germination rate (percent of radicle emergence) was recorded daily until no further germination occurred. Seeds of WT, CaWRKY27-OE4, and OE9 lines were treated at 42°C for 15 h and then returned to 25°C for germination. Data represent the mean (n = 8 at 25°C, n = 5 at 42°C) ± SE, and each replicate consisted of 32-34 seeds.

Expression of thermotolerance-associated genes were monitored by qRT-PCR in wild type (K326) and CaWRKY27-OE4 plants at 24 and 48 h after heat stress (42°C). (A,B), Relative expression of the ROS-scavenging enzyme genes NtGST1 and NtCAT1 in heat-treated CaWRKY27-OE4 and WT plants. (C–G) Expression of the ethylene biosynthesis associated genes NtACC deaminase, NtACS1, NtACS6, NtEFE26, and NtACC Oxidase, in heat-treated CaWRKY27-OE4 and WT plants. (H) Expression of the heat-shock factor NtHSF2 in heat-treated CaWRKY27-OE4 and WT plants. (I,J) Expression of the heat-shock proteins NtHSP18 and NtHSP90 in heat-treated CaWRKY27-OE4 and WT plants. The transcript level of each gene was normalized against CaActin, followed by normalization against the transcript level of the gene in heat-treated WT plants. Data represent the mean ± SE of three biological replicates. Asterisks indicate significant differences compared with WT plants (SNK-test, ∗P < 0.05 or ∗∗P < 0.01).

CaWRKY27 expression was repressed in isolated pepper leaves under heat stress with ROS scavenging reagent. (A) Accumulation of H2O2 were detected via DAB staining at 3 h after heat stress (33°C) and 30 min after recovery (25°C) with or without 10 mm AsA (ascorbic acid), 100 μM DPI (diphenyleneiodonium chloride) and 100 μM quinacrine in isolated pepper leaves. (B) CaWRKY27 expression was determined via qRT-PCR at 3 h after heat stress (33°C) and 30 min after recovery (25°C) with or without 10 mm AsA (ascorbic acid) in isolated pepper leaves. Data represent the mean ± SE of three biological replicates.

Sequences of primers used in this study.

References

- Alvarez M. E., Pennell R. I., Meijer P. J., Ishikawa A., Dixon R. A., Lamb C. (1998). Reactive oxygen intermediates mediate a systemic signal network in the establishment of plant immunity. Cell 92 773–784. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81405-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alves M. S., Dadalto S. P., Goncalves A. B., de Souza G. B., Barros V. A., Fietto L. G. (2014). Transcription factor functional protein-protein interactions in plant defense responses. Proteomes 2 85–106. 10.3390/proteomes2010085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andronis E. A., Moschou P. N., Toumi I., Roubelakis-Angelakis K. A. (2014). Peroxisomal polyamine oxidase and NADPH-oxidase cross-talk for ROS homeostasis which affects respiration rate in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 5:132. 10.3389/fpls.2014.00132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Rejeb K., Benzarti M., Debez A., Bailly C., Savoure A., Abdelly C. (2015). NADPH oxidase-dependent H2O2 production is required for salt-induced antioxidant defense in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Plant Physiol. 174 5–15. 10.1016/j.jplph.2014.08.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai H., Yang S., Yan Y., Xiao Z., Cheng J., Wu J., et al. (2015). CaWRKY6 transcriptionally activates CaWRKY40, regulates Ralstonia solanacearum resistance, and confers high-temperature and high-humidity tolerance in pepper. J. Exp. Bot. 66 3163–3174. 10.1093/jxb/erv125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao L. M., Liu Y. Q., Chen D. Y., Xue X. Y., Mao Y. B., Chen X. Y. (2017). Arabidopsis transcription factors SPL1 and SPL12 confer plant thermotolerance at reproductive stage. Mol. Plant 10 735–748. 10.1016/j.molp.2017.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H. J., Huang C. S., Huang G. J., Chow T. J., Lin Y. H. (2013). NADPH oxidase inhibitor diphenyleneiodonium and reduced glutathione mitigate ethephon-mediated leaf senescence, H2O2 elevation and senescence-associated gene expression in sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas). J. Plant Physiol. 170 1471–1483. 10.1016/j.jplph.2013.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N., Goodwin P. H., Hsiang T. (2003). The role of ethylene during the infection of Nicotiana tabacum by Colletotrichum destructivum. J. Exp. Bot. 54 2449–2456. 10.1093/jxb/erg28954/392/2449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi Y., Yang Y., Zhou Y., Zhou J., Fan B., Yu J. Q., et al. (2013). Protein-protein interactions in the regulation of WRKY transcription factors. Mol. Plant 6 287–300. 10.1093/mp/sst026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury F. K., Rivero R. M., Blumwald E., Mittler R. (2017). Reactive oxygen species, abiotic stress and stress combination. Plant J. 90 856–867. 10.1111/tpj.13299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke S. M., Cristescu S. M., Miersch O., Harren F. J., Wasternack C., Mur L. A. (2009). Jasmonates act with salicylic acid to confer basal thermotolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 182 175–187. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02735.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke S. M., Mur L. A. J., Wood J. E., Scott I. M. (2004). Salicylic acid dependent signaling promotes basal thermotolerance but is not essential for acquired thermotolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 38 432–447. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02054.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang F. F., Wang Y. N., She J. J., Lei Y. F., Liu Z. Q., Eulgem T., et al. (2014). Overexpression of CaWRKY27, a subgroup IIe WRKY transcription factor of Capsicum annuum, positively regulates tobacco resistance to Ralstonia solanacearum infection. Physiol. Plant. 150 397–411. 10.1111/ppl.12093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang F. F., Wang Y. N., Yu L., Eulgem T., Lai Y., Liu Z. Q., et al. (2013). CaWRKY40, a WRKY protein of pepper, plays an important role in the regulation of tolerance to heat stress and resistance to Ralstonia solanacearum infection. Plant Cell Environ. 36 757–774. 10.1111/pce.12011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dat J. F., Lopez-Delgado H., Foyer C. H., Scott I. M. (1998). Parallel changes in H2O2 and catalase during thermotolerance induced by salicylic acid or heat acclimation in mustard seedlings. Plant Physiol. 116 1351–1357. 10.1104/pp.116.4.1351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davletova S., Rizhsky L., Liang H., Shengqiang Z., Oliver D. J., Coutu J., et al. (2005). Cytosolic ascorbate peroxidase 1 is a central component of the reactive oxygen gene network of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 17 268–281. 10.1105/tpc.104.026971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fragkostefanakis S., Roth S., Schleiff E., Scharf K. D. (2015). Prospects of engineering thermotolerance in crops through modulation of heat stress transcription factor and heat shock protein networks. Plant Cell Environ. 38 1881–1895. 10.1111/pce.12396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita M., Fujita Y., Noutoshi Y., Takahashi F., Narusaka Y., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K., et al. (2006). Crosstalk between abiotic and biotic stress responses: a current view from the points of convergence in the stress signaling networks. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 9 436–442. 10.1016/j.pbi.2006.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gemes K., Kim Y. J., Park K. Y., Moschou P. N., Andronis E., Valassaki C., et al. (2016). An NADPH-Oxidase/Polyamine Oxidase feedback loop controls oxidative burst under salinity. Plant Physiol. 172 1418–1431. 10.1104/pp.16.01118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan Q., Yue X., Zeng H., Zhu J. (2014). The protein phosphatase RCF2 and its interacting partner NAC019 are critical for heat stress-responsive gene regulation and thermotolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 26 438–453. 10.1105/tpc.113.118927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S. J., Zhou H. Y., Zhang X. S., Li X. G., Meng Q. W. (2007). Overexpression of CaHSP26 in transgenic tobacco alleviates photoinhibition of PSII and PSI during chilling stress under low irradiance. J. Plant Physiol. 164 126–136. 10.1016/j.jplph.2006.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He G. H., Xu J. Y., Wang Y. X., Liu J. M., Li P. S., Chen M., et al. (2016). Drought-responsive WRKY transcription factor genes TaWRKY1 and TaWRKY33 from wheat confer drought and/or heat resistance in Arabidopsis. BMC Plant Biol. 16:116. 10.1186/s12870-016-0806-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y. C., Niu C. Y., Yang C. R., Jinn T. L. (2016). The heat stress factor HSFA6b connects ABA signaling and ABA-mediated heat responses. Plant Physiol. 172 1182–1199. 10.1104/pp.16.00860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iba K. (2002). Acclimative response to temperature stress in higher plants: approaches of gene engineering for temperature tolerance. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 53 225–245. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.53.100201.160729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia L., Chu H., Wu D., Feng M., Zhao L. (2014). Role of calmodulin in thermotolerance. Plant Signal. Behav. 9:e28887 10.4161/psb.28887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karanja B. K., Fan L., Xu L., Wang Y., Zhu X., Tang M., et al. (2017). Genome-wide characterization of the WRKY gene family in radish (Raphanus sativus L.) reveals its critical functions under different abiotic stresses. Plant Cell Rep. 36 1757–1773. 10.1007/s00299-017-2190-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karkonen A., Kuchitsu K. (2015). Reactive oxygen species in cell wall metabolism and development in plants. Phytochemistry 112 22–32. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2014.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim N. H., Choi H. W., Hwang B. K. (2010). Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria effector AvrBsT induces cell death in pepper, but suppresses defense responses in tomato. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 23 1069–1082. 10.1094/Mpmi-23-8-1069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschner M., Winkelhaus S., Thierfelder J. M., Nover L. (2000). Transient expression and heat-stress-induced co-aggregation of endogenous and heterologous small heat-stress proteins in tobacco protoplasts. Plant J. 24 397–411. 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00887.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotak S., Larkindale J., Lee U., von Koskull-Doring P., Vierling E., Scharf K. D. (2007). Complexity of the heat stress response in plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 10 310–316. 10.1016/j.pbi.2007.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkindale J., Huang B. (2004). Thermotolerance and antioxidant systems in Agrostis stolonifera: involvement of salicylic acid, abscisic acid, calcium, hydrogen peroxide, and ethylene. J. Plant Physiol. 161 405–413. 10.1078/0176-1617-01239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkindale J., Vierling E. (2008). Core genome responses involved in acclimation to high temperature. Plant Physiol. 146 748–761. 10.1104/pp.107.112060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine A., Tenhaken R., Dixon R., Lamb C. (1994). H2O2 from the oxidative burst orchestrates the plant hypersensitive disease resistance response. Cell 79 583–593. 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90544-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Fu Q., Huang W., Yu D. (2009). Functional analysis of an Arabidopsis transcription factor WRKY25 in heat stress. Plant Cell Rep. 28 683–693. 10.1007/s00299-008-0666-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S. J., Fu Q. T., Chen L. G., Huang W. D., Yu D. Q. (2011). Arabidopsis thaliana WRKY25, WRKY26, and WRKY33 coordinate induction of plant thermotolerance. Planta 233 1237–1252. 10.1007/s00425-011-1375-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S. J., Zhou X., Chen L. G., Huang W. D., Yu D. Q. (2010). Functional characterization of Arabidopsis thaliana WRKY39 in heat stress. Mol. Cells 29 475–483. 10.1007/s10059-010-0059-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H. T., Sun D. Y., Zhou R. G. (2005). Ca2 + and AtCaM3 are involved in the expression of heat shock protein gene in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Environ. 28 1276–1284. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01365.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Kracher B., Ziegler J., Birkenbihl R. P., Somssich I. E. (2015). Negative regulation of ABA signaling by WRKY33 is critical for Arabidopsis immunity towards Botrytis cinerea 2100. eLife 4:e07295. 10.7554/eLife.07295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z. M., Yue M. M., Yang D. Y., Zhu S. B., Ma N. N., Meng Q. W. (2017). Over-expression of SlJA2 decreased heat tolerance of transgenic tobacco plants via salicylic acid pathway. Plant Cell Rep. 36 529–542. 10.1007/s00299-017-2100-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellidou I., Karamanoli K., Beris D., Haralampidis K., Constantinidou H. I. A., Roubelakis-Angelakis K. A. (2017). Underexpression of apoplastic polyamine oxidase improves thermotolerance in Nicotiana tabacum. J. Plant Physiol. 218 171–174. 10.1016/j.jplph.2017.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mignolet-Spruyt L., Xu E., Idanheimo N., Hoeberichts F. A., Muhlenbock P., Brosche M., et al. (2016). Spreading the news: subcellular and organellar reactive oxygen species production and signalling. J. Exp. Bot. 67 3831–3844. 10.1093/jxb/erw080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittler R. (2002). Oxidative stress, antioxidants and stress tolerance. Trends Plant Sci. 7 405–410. 10.1016/S1360-1385(02)02312-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittler R., Finka A., Goloubinoff P. (2012). How do plants feel the heat? Trends Biochem. Sci. 37 118–125. 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittler R., Vanderauwera S., Gollery M., Van Breusegem F. (2004). Reactive oxygen gene network of plants. Trends Plant Sci. 9 490–498. 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller I. M. (2001). Plant mitochondria and oxidative stress: electron transport, NADPH turnover, and metabolism of reactive oxygen species. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. 52 561–591. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.52.1.561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales J., Kadota Y., Zipfel C., Molina A., Torres M. A. (2016). The Arabidopsis NADPH oxidases RbohD and RbohF display differential expression patterns and contributions during plant immunity. J. Exp. Bot. 67 1663–1676. 10.1093/jxb/erv558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishizawa-Yokoi A., Nosaka R., Hayashi H., Tainaka H., Maruta T., Tamoi M., et al. (2011). HsfA1d and HsfA1e involved in the transcriptional regulation of HsfA2 function as key regulators for the Hsf signaling network in response to environmental stress. Plant Cell Physiol. 52 933–945. 10.1093/pcp/pcr045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nover L., Scharf K. D., Gagliardi D., Vergne P., Czarnecka-Verner E., Gurley W. B. (1996). The Hsf world: classification and properties of plant heat stress transcription factors. Cell Stress Chaperones 1 215–223. 10.1379/1466-12681996001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh S. Y., Kim J. H., Park M. J., Kim S. M., Yoon C. S., Joo Y. M., et al. (2005). Induction of heat shock protein 72 in C6 glioma cells by methyl jasmonate through ROS-dependent heat shock factor 1 activation. Int. J. Mol. Med. 16 833–839. 10.3892/ijmm.16.5.833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohama N., Kusakabe K., Mizoi J., Zhao H. M., Kidokoro S., Koizumi S., et al. (2016). The transcriptional cascade in the heat stress response of Arabidopsis is strictly regulated at the level of transcription factor expression. Plant Cell 28 181–201. 10.1105/tpc.15.00435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohama N., Sato H., Shinozaki K., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. (2017). Transcriptional regulatory network of plant heat stress response. Trends Plant Sci. 22 53–65. 10.1016/j.tplants.2016.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozgur R., Uzilday B., Sekmen A. H., Turkan I. (2015). The effects of induced production of reactive oxygen species in organelles on endoplasmic reticulum stress and on the unfolded protein response in Arabidopsis. Ann. Bot. 116 541–553. 10.1093/aob/mcv072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S. M., Kim K. P., Joe M. K., Lee M. O., Koo H. J., Hong C. B. (2015). Tobacco class I cytosolic small heat shock proteins are under transcriptional and translational regulations in expression and heterocomplex prevails under the high-temperature stress condition in vitro. Plant Cell Environ. 38 767–776. 10.1111/pce.12436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellinen R., Palva T., Kangasjarvi J. (1999). Subcellular localization of ozone-induced hydrogen peroxide production in birch (Betula pendula) leaf cells. Plant J. 20 349–356. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1999.00613.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao B., Zhang Q., Liu D., Wang H., Yin J., Wang R., et al. (2015). A calcium-binding protein, rice annexin OsANN1, enhances heat stress tolerance by modulating the production of H2O2. J. Exp. Bot. 66 5853–5866. 10.1093/jxb/erv294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Queitsch C., Hong S. W., Vierling E., Lindquist S. (2000). Heat shock protein 101 plays a crucial role in thermotolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 12 479–492. 10.1105/tpc.12.4.479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn P. J. (1988). Effects of temperature on cell membranes. Symp. Soc. Exp. Biol. 42 237–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis R. R., da Cunha B. A., Martins P. K., Martins M. T., Alekcevetch J. C., Chalfun A., et al. (2014). Induced over-expression of AtDREB2A CA improves drought tolerance in sugarcane. Plant Sci. 22 59–68. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2014.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizhsky L., Liang H. J., Mittler R. (2002). The combined effect of drought stress and heat shock on gene expression in tobacco. Plant Physiol. 130 1143–1151. 10.1104/pp.006858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushton P. J., Somssich I. E., Ringler P., Shen Q. J. (2010). WRKY transcription factors. Trends Plant Sci. 15 247–258. 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakuma Y., Maruyama K., Qin F., Osakabe Y., Shinozaki K., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. (2006). Dual function of an Arabidopsis transcription factor DREB2A in water-stress-responsive and heat-stress-responsive gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103 18822–18827. 10.1073/pnas.0605639103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvi P., Kamble N. U., Majee M. (2018). Stress-Inducible Galactinol Synthase of Chickpea (CaGolS) is implicated in heat and oxidative stress tolerance through reducing stress-induced excessive reactive oxygen species accumulation. Plant Cell Physiol. 59 155–166. 10.1093/pcp/pcx170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena I., Srikanth S., Chen Z. (2016). Cross talk between H2O2 and interacting signal molecules under plant stress response. Front. Plant Sci. 7:570. 10.3389/fpls.2016.00570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoji T., Kato K., Sekine M., Yoshida K., Shinmyo A. (2000). Two types of heat shock factors in cultured tobacco cells. Plant Cell Rep. 19 414–420. 10.1007/s002990050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Q., Li D., Dai Y., Liu S., Huang L., Hong Y., et al. (2015). Characterization, expression patterns and functional analysis of the MAPK and MAPKK genes in watermelon (Citrullus lanatus). BMC Plant Biol. 15:298. 10.1186/s12870-015-0681-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava R., Deng Y., Howell S. H. (2014). Stress sensing in plants by an ER stress sensor/transducer, bZIP28. Front. Plant Sci. 5:59. 10.3389/fpls.2014.00059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki N., Miller G., Morales J., Shulaev V., Torres M. A., Mittler R. (2011). Respiratory burst oxidases: the engines of ROS signaling. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 14 691–699. 10.1016/j.pbi.2011.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H., Chen Z., Du H., Liu Y., Klessig D. F. (1997). Development of necrosis and activation of disease resistance in transgenic tobacco plants with severely reduced catalase levels. Plant J. 11 993–1005. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1997.11050993.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Y. C., Fan M., Qin Z. X., Lv H. J., Wang M. M., Zhang Z., et al. (2018). Hydrogen peroxide positively regulates brassinosteroid signaling through oxidation of the BRASSINAZOLE-RESISTANT1 transcription factor. Nat. Commun. 9:1063. 10.1038/s41467-018-03463-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi P., Rabara R. C., Choudhary M. K., Miller M. A., Huang Y. S., Shen Q. J., et al. (2015). The interactome of soybean GmWRKY53 using yeast 2-hybrid library screening to saturation. Plant Signal. Behav. 10:e1028705. 10.1080/15592324.2015.1028705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkov R. A., Panchuk I. I., Mullineaux P. M., Schoffl F. (2006). Heat stress-induced H2O2 is required for effective expression of heat shock genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Biol. 61 733–746. 10.1007/s11103-006-0045-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahid A. (2007). Physiological implications of metabolite biosynthesis for net assimilation and heat-stress tolerance of sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum) sprouts. J. Plant Res. 120 219–228. 10.1007/s10265-006-0040-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Guo Y., Jia L., Chu H., Zhou S., Chen K., et al. (2014). Hydrogen peroxide acts upstream of nitric oxide in the heat shock pathway in Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant Physiol. 164 2184–2196. 10.1104/pp.113.229369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Huang W., Yang Z., Liu J., Huang B. (2016). Transcriptional regulation of heat shock proteins and ascorbate peroxidase by CtHsfA2b from African bermudagrass conferring heat tolerance in Arabidopsis. Sci. Rep. 6:28021. 10.1038/srep28021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X., Shiroto Y., Kishitani S., Ito Y., Toriyama K. (2009). Enhanced heat and drought tolerance in transgenic rice seedlings overexpressing OsWRKY11 under the control of HSP101 promoter. Plant Cell Rep. 28 21–30. 10.1007/s00299-008-0614-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoda H., Hiroi Y., Sano H. (2006). Polyamine oxidase is one of the key elements for oxidative burst to induce programmed cell death in tobacco cultured cells. Plant Physiol. 142 193–206. 10.1104/pp.106.080515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zang X. S., Geng X. L., Wang F., Liu Z. S., Zhang L. Y., Zhao Y., et al. (2017). Overexpression of wheat ferritin gene TaFER-5B enhances tolerance to heat stress and other abiotic stresses associated with the ROS scavenging. BMC Plant Biol. 17:14. 10.1186/s12870-016-0958-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C., Wang D. D., Yang C. H., Kong N., Shi Z., Zhao P., et al. (2017). Genome-wide identification of the potato WRKY transcription factor family. PLoS One 12:e0181573. 10.1371/journal.pone.0181573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Z., Qamar S. A., Chen Z., Mengiste T. (2006). Arabidopsis WRKY33 transcription factor is required for resistance to necrotrophic fungal pathogens. Plant J. 48 592–605. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02901.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J., Xu X. C., Cao J. J., Yin L. L., Xia X. J., Shi K., et al. (2018). Heat shock factor HsfA1a Is essential for R gene-mediated nematode resistance and triggers H2O2 production. Plant Physiol. 176 2456–2471. 10.1104/pp.17.01281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

CaWRKY27 promoter motifs and expression in silenced and overexpression lines. (A) Nucleotide sequences from the CaWRKY27 5’ flanking promoter region. The four heat stress response elements (HSEs) that may act as cis/trans motifs are marked by arrows. (B) Relative expression of CaWRKY27 in PYL-279, PYL-279-wrky27, and PYL-279-wrky27-3’utr pepper plants that had been either unchallenged or challenged with heat stress. CaWRKY27 relative expression was normalized against CaActin, followed by normalization against the CaWRKY27 expression in the PYL-279 control. Data represent the mean ± SE of three biological replicates. (C) Transcription of CaWRKY27 in CaWRKY27-overexpressing Arabidopsis plant lines was determined via semi-quantitative PCR, and normalized against AtUBQ10 expression.

Phenotypes of CaWRKY27-overexpressing tobacco lines. (A) Relative expression of CaWRKY27 was analyzed in nine CaWRKY27-overexpressing lines and WT (K326) plants with qRT-PCR. CaWRKY27 expression was normalized against NtEF1α, followed by normalization against the CaWRKY27 expression in the WT. Data represent the mean ± SE of three biological replicates. (B–D) Phenotypes of 15-, 30-, and 55-day-old CaWRKY27-overexpressing lines and WT plants that were treated at 42°C for 48 h, then returned to 25°C to recover for 48 h. (E) Effect of heat on seed germination rate (percent of radicle emergence) was recorded daily until no further germination occurred. Seeds of WT, CaWRKY27-OE4, and OE9 lines were treated at 42°C for 15 h and then returned to 25°C for germination. Data represent the mean (n = 8 at 25°C, n = 5 at 42°C) ± SE, and each replicate consisted of 32-34 seeds.

Expression of thermotolerance-associated genes were monitored by qRT-PCR in wild type (K326) and CaWRKY27-OE4 plants at 24 and 48 h after heat stress (42°C). (A,B), Relative expression of the ROS-scavenging enzyme genes NtGST1 and NtCAT1 in heat-treated CaWRKY27-OE4 and WT plants. (C–G) Expression of the ethylene biosynthesis associated genes NtACC deaminase, NtACS1, NtACS6, NtEFE26, and NtACC Oxidase, in heat-treated CaWRKY27-OE4 and WT plants. (H) Expression of the heat-shock factor NtHSF2 in heat-treated CaWRKY27-OE4 and WT plants. (I,J) Expression of the heat-shock proteins NtHSP18 and NtHSP90 in heat-treated CaWRKY27-OE4 and WT plants. The transcript level of each gene was normalized against CaActin, followed by normalization against the transcript level of the gene in heat-treated WT plants. Data represent the mean ± SE of three biological replicates. Asterisks indicate significant differences compared with WT plants (SNK-test, ∗P < 0.05 or ∗∗P < 0.01).

CaWRKY27 expression was repressed in isolated pepper leaves under heat stress with ROS scavenging reagent. (A) Accumulation of H2O2 were detected via DAB staining at 3 h after heat stress (33°C) and 30 min after recovery (25°C) with or without 10 mm AsA (ascorbic acid), 100 μM DPI (diphenyleneiodonium chloride) and 100 μM quinacrine in isolated pepper leaves. (B) CaWRKY27 expression was determined via qRT-PCR at 3 h after heat stress (33°C) and 30 min after recovery (25°C) with or without 10 mm AsA (ascorbic acid) in isolated pepper leaves. Data represent the mean ± SE of three biological replicates.

Sequences of primers used in this study.