Abstract

Background

Severe stressors can induce preterm birth (PTB; gestation <37 weeks), with such stressors including social and economic threats, interpersonal violence, hate crimes and severe sociopolitical stressors (ie, arising from political leaders’ threatening rhetoric or from political legislation). We analysed temporal changes in risk of PTB among immigrant, Hispanic and Muslim populations targeted in the US 2016 presidential election and its aftermath.

Methods

Trend analysis of all singleton births in New York City from 1 September 2015 to 31 August 2017 (n=230 105).

Results

Comparing the period before the US presidential nomination (1 September 2015 to 31 July 2016) to the post-inauguration period (1 January 2017 to 31 August 2017), the overall PTB rate increased from 7.0% to 7.3% (relative risk (RR): 1.04; 95% CI 1.00 to 1.07). Among Hispanic women, the highest post-inauguration versus pre-inauguration increase occurred among foreign-born Hispanic women with Mexican or Central American ancestry (RR: 1.15; 95% CI 1.01 to 1.31). The post-inauguration versus pre-inauguration PTB rate also was higher for women from the Middle East/North Africa and from the travel ban countries, although non-significant due to the small number of events.

Conclusion

Severe sociopolitical stressors may contribute to increases in the risk of PTB among targeted populations.

Keywords: ethnicity, health inequalities, policy, reproductive health, surveillance

Introduction

Severe stress, induced by social and economic threats, interpersonal violence and hate crimes, can increase risk of preterm birth (PTB; gestation <37 weeks), especially spontaneous PTB,1–4 as can severe sociopolitical stressors (ie, stressors that arise from political leaders’ threatening rhetoric or from political legislation3 5). Recent changes in such stressors, as tied to the US 2016 presidential election and its aftermath,5–11 including heightened anti-immigrant, anti-Hispanic and anti-Muslim policies, discrimination and hate crimes,5–11 could potentially constitute severe sociopolitical stressors with adverse impacts on health, including increased PTB rates.3–8 Such stressors could result in greater relative increases in risk among immigrant versus native-born populations, even if the former’s absolute rates remain lower (due to the well-known ‘healthy immigrant’ effect12).

In the USA, several studies have reported increased risk of PTB and, related, low birth weight, among populations exposed to sociopolitical stressors, including heightened profiling and deportation of immigrants, which can both increase psychological distress and decrease access to health services.3–8 An analysis of one of the largest single-site federal immigration raids in the USA, which took place in 2008 in Postville, Iowa, found that Hispanic mothers, both US born and immigrant, uniquely experienced a 1.24-fold increased risk (95% CI 0.98 to 1.57) of having a low birthweight baby during the year after, compared with the year preceding, the raid; no such increase was observed among the non-Hispanic White mothers.3 A recent report by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that immigrant families experienced fear and uncertainty which adversely impacted their children’s health.6

Motivated by the public health responsibility of monitoring trends in population health,8 we accordingly examined PTB rates, given evidence of sensitivity of PTB rates to temporally acute stressors.1–4 We focused on three time periods, defined in relation to phases of the 2016 election cycle and the corresponding escalating political rhetoric, policies and hate crimes.6–11 13–15

Time period 1: during campaign, before US presidential candidate nominations (September 2015 to July 2016)

Examples of this period’s rising rhetoric9 include candidate Trump’s call for a border wall, stating, ‘When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best … They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists’14 and also his call for ‘a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States.’13

Time period 2: nomination to inauguration (August 2016 to December 2016)

Escalation of the threatening anti-immigrant, anti-Hispanic and anti-Muslim rhetoric and policy proposals by nominee Trump8–10 and corresponding hate crimes.11

Time period 3: post-inauguration (January 2017 to August 2017)

President Trump announced the first federal travel ban in January 2017, which targeted Iran, Iraq, Syria, Yemen, Sudan, Libya and Somalia.10 Also in January 2017, the President issued an Executive Order to establish a border wall with Mexico and to freeze federal funding to sanctuary cities; in mid-February Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents intensified raids nationwide; and in February 2017 Homeland Security issued memos that tightened deportation and detention rules, followed by further intensified ICE raids and fear of such raids, including in New York City (NYC).7 8 10

Our hypothesis was that mothers belonging to social groups singled out by anti-immigrant, anti-Hispanic and anti-Muslim rhetoric, policies and violence would be more likely to have a PTB post-inauguration.

Methods

We conducted a trend analysis utilising birth certificates from 1 September 2015 to 31 August 2017 for all singleton births that occurred in NYC (n=230 105). PTB was defined as a birth that occurred before 37 weeks of gestation, using data based on obstetrical estimates as recorded in the birth certificate. We used the self-report data from the birth certificate on maternal ‘race’, ‘ancestry’ and ‘nativity’ to classify mothers in relation to being at risk of anti-immigrant, anti-Hispanic and anti-Muslim discrimination, using the categories delineated in table 1.16–18

Table 1.

Preterm birth rate and rate ratios for each time period by nativity, race/ethnicity and ancestry, New York City, 1 September 2015 to 31 August 2017

| Total births (n) | Preterm births (n) | PTB rate (%) | Time period 1: during campaign, before US presidential nominations | Time period 2: nomination to inauguration | Time period 3: post-inauguration | Rate ratio (time period 2/time period 1) and 95% CI | Rate ratio (time period 3/time period 1) and 95% CI | |||

| Rate (%) | Rate (%) | Rate (%) | Rate ratio | 95% CI | Rate ratio | 95% CI | ||||

| Population (n) | 230 105 | 16 331 | 7.1 | 7.0 | 7.1 | 7.3 | 1.01 | 0.97 to 1.05 | 1.04 | 1.00 to 1.07 |

| Nativity | ||||||||||

| US born | 110 510 | 8164 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 7.2 | 7.5 | 0.98 | 0.93 to 1.04 | 1.02 | 0.97 to 1.07 |

| Foreign born | 119 456 | 8150 | 6.8 | 6.7 | 6.9 | 7.0 | 1.03 | 0.98 to 1.09 | 1.06 | 1.01 to 1.11 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||

| Hispanic | 65 799 | 5126 | 7.8 | 7.7 | 7.5 | 8.2 | 0.97 | 0.91 to 1.04 | 1.07 | 1.01 to 1.13 |

| Asian and Pacific Islander | 40 488 | 2656 | 6.6 | 6.5 | 6.5 | 6.7 | 1.00 | 0.91 to 1.10 | 1.02 | 0.94 to 1.11 |

| White non-Hispanic | 77 874 | 3902 | 5.0 | 4.9 | 5.2 | 5.0 | 1.07 | 0.98 to 1.15 | 1.01 | 0.94 to 1.08 |

| Black non-Hispanic | 42 774 | 4410 | 10.3 | 10.2 | 10.0 | 10.6 | 0.98 | 0.91 to 1.05 | 1.04 | 0.98 to 1.11 |

| Other | 3004 | 218 | 7.3 | 6.8 | 8.1 | 7.4 | 1.18 | 0.85 to 1.64 | 1.08 | 0.80 to 1.45 |

| Ancestry | ||||||||||

| MENA (travel ban+rest of MENA) | 7270 | 344 | 4.7 | 4.5 | 5.1 | 4.8 | 1.12 | 0.86 to 1.47 | 1.07 | 0.85 to 1.36 |

| MENA+Arab+Kurd+Muslim+Sikh | 8058 | 384 | 4.8 | 4.6 | 4.7 | 5.0 | 1.02 | 0.79 to 1.32 | 1.08 | 0.86 to 1.34 |

| Travel ban | 2405 | 113 | 4.7 | 4.6 | 4.7 | 4.8 | 1.01 | 0.61 to 1.65 | 1.03 | 0.69 to 1.54 |

| Rest of MENA | 4865 | 231 | 4.7 | 4.5 | 5.2 | 4.9 | 1.18 | 0.85 to 1.62 | 1.09 | 0.81 to 1.46 |

| Mexico and Central America | 17 156 | 1289 | 7.5 | 7.2 | 7.1 | 8.2 | 0.98 | 0.85 to 1.13 | 1.13 | 1.01 to 1.28 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 5841 | 407 | 7.0 | 6.7 | 7.5 | 7.0 | 1.13 | 0.89 to 1.43 | 1.05 | 0.84 to 1.30 |

| Caribbean | 45 237 | 3892 | 8.6 | 8.5 | 8.3 | 9.0 | 0.98 | 0.90 to 1.06 | 1.05 | 0.98 to 1.13 |

| North America other than USA | 483 | 22 | 4.6 | 3.7 | 5.0 | 5.5 | 1.34 | 0.45 to 4.02 | 1.48 | 0.58 to 3.76 |

| USA | 49 157 | 4084 | 8.3 | 8.3 | 8.2 | 8.5 | 0.99 | 0.92 to 1.07 | 1.02 | 0.96 to 1.09 |

| South America | 14 320 | 1081 | 7.5 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 7.8 | 1.00 | 0.86 to 1.16 | 1.05 | 0.92 to 1.20 |

| Rest of Asia excluding MENA | 41 714 | 2623 | 6.3 | 6.3 | 6.3 | 6.3 | 1.00 | 0.91 to 1.10 | 1.00 | 0.92 to 1.09 |

| Europe | 27 072 | 1323 | 4.9 | 4.7 | 5.2 | 4.9 | 1.10 | 0.96 to 1.26 | 1.02 | 0.91 to 1.16 |

| Oceania | 324 | 18 | 5.6 | 8.1 | 4.3 | 2.8 | 0.53 | 0.15 to 1.83 | 0.35 | 0.10 to 1.21 |

| Jewish or Hebrew | 10 354 | 440 | 4.2 | 4.4 | 4.6 | 3.7 | 1.04 | 0.82 to 1.32 | 0.84 | 0.68 to 1.04 |

| Nativity and ethnicity | ||||||||||

| US born | ||||||||||

| Hispanic | 28 380 | 2451 | 8.6 | 8.5 | 8.4 | 9.0 | 0.98 | 0.89 to 1.09 | 1.06 | 0.97 to 1.15 |

| Asian and Pacific Islander | 4581 | 291 | 6.4 | 6.6 | 6.1 | 6.2 | 0.93 | 0.69 to 1.24 | 0.95 | 0.74 to 1.23 |

| White non-Hispanic | 52 686 | 2700 | 5.1 | 5.2 | 5.2 | 5.0 | 1.02 | 0.92 to 1.12 | 0.97 | 0.89 to 1.05 |

| Black non-Hispanic | 22 975 | 2570 | 11.2 | 11.3 | 10.3 | 11.7 | 0.92 | 0.83 to 1.01 | 1.04 | 0.96 to 1.13 |

| Other | 1800 | 142 | 7.9 | 7.2 | 8.5 | 8.4 | 1.17 | 0.78 to 1.76 | 1.16 | 0.80 to 1.66 |

| Ancestry | ||||||||||

| Travel ban | 350 | 10 | 2.9 | 3.0 | 1.6 | 3.4 | 0.53 | 0.06 to 4.55 | 1.13 | 0.31 to 4.14 |

| Rest of MENA | 527 | 19 | 3.6 | 3.2 | 2.8 | 4.6 | 0.87 | 0.24 to 3.25 | 1.42 | 0.54 to 3.72 |

| Mexico and Central America | 3917 | 283 | 7.2 | 6.9 | 6.8 | 7.9 | 0.99 | 0.73 to 1.34 | 1.14 | 0.88 to 1.46 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 170 | 17 | 10.0 | 5.9 | 16.1 | 11.3 | 2.74 | 0.78 to 9.65 | 1.92 | 0.60 to 6.12 |

| Caribbean | 21 155 | 1899 | 9.0 | 8.9 | 8.5 | 9.4 | 0.96 | 0.85 to 1.07 | 1.05 | 0.95 to 1.16 |

| North America other than USA | 30 | 1 | 3.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 10.0 | – | – | – | – |

| USA | 44 147 | 3614 | 8.2 | 8.2 | 8.0 | 8.3 | 0.97 | 0.89 to 1.05 | 1.01 | 0.94 to 1.09 |

| South America | 2566 | 186 | 7.2 | 6.3 | 7.1 | 8.8 | 1.13 | 0.78 to 1.62 | 1.40 | 1.02 to 1.92 |

| Rest of Asia excluding MENA | 4367 | 269 | 6.2 | 6.4 | 5.9 | 5.9 | 0.92 | 0.68 to 1.25 | 0.93 | 0.71 to 1.21 |

| Europe | 15 456 | 818 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 1.00 | 0.83 to 1.19 | 1.01 | 0.86 to 1.17 |

| Oceania | 46 | 4 | 8.7 | 14.3 | 0.0 | 6.7 | 0 | – | 0.47 | 0.05 to 4.36 |

| Jewish or Hebrew | 8977 | 383 | 4.3 | 4.7 | 4.6 | 3.5 | 0.98 | 0.76 to 1.26 | 0.75 | 0.59 to 0.94 |

| MENA+Arab+Kurd+Muslim+Sikh | 1012 | 34 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 2.0 | 4.5 | 0.64 | 0.22 to 1.91 | 1.43 | 0.71 to 2.90 |

| Foreign born | ||||||||||

| Hispanic | 37 405 | 2673 | 7.1 | 7.0 | 6.7 | 7.6 | 0.96 | 0.87 to 1.06 | 1.08 | 0.99 to 1.17 |

| Asian and Pacific Islander | 35 899 | 2364 | 6.6 | 6.5 | 6.6 | 6.7 | 1.01 | 0.91 to 1.12 | 1.03 | 0.94 to 1.13 |

| White non-Hispanic | 25 132 | 1200 | 4.8 | 4.4 | 5.3 | 4.9 | 1.18 | 1.03 to 1.37 | 1.12 | 0.98 to 1.27 |

| Black non-Hispanic | 19 778 | 1835 | 9.3 | 9.0 | 9.6 | 9.4 | 1.07 | 0.96 to 1.20 | 1.04 | 0.94 to 1.15 |

| Other | 1204 | 76 | 6.3 | 6.2 | 7.4 | 5.7 | 1.19 | 0.69 to 2.05 | 0.91 | 0.54 to 1.54 |

| MENA | 7995 | 417 | 5.2 | 5.0 | 5.4 | 5.4 | 1.09 | 0.85 to 1.39 | 1.10 | 0.89 to 1.36 |

| Seven countries in travel ban | 2495 | 131 | 5.3 | 5.0 | 5.3 | 5.5 | 1.06 | 0.67 to 1.68 | 1.12 | 0.77 to 1.63 |

| Rest of MENA | 5500 | 286 | 5.2 | 5.0 | 5.4 | 5.4 | 1.10 | 0.82 to 1.47 | 1.08 | 0.83 to 1.40 |

| Mexico + Central America | 13 414 | 1022 | 7.6 | 7.3 | 7.2 | 8.4 | 0.99 | 0.85 to 1.16 | 1.15 | 1.01 to 1.31 |

| Caribbean | 26 293 | 2227 | 8.5 | 8.2 | 8.4 | 8.9 | 1.02 | 0.92 to 1.13 | 1.08 | 0.98 to 1.18 |

| South America | 12 845 | 1014 | 7.9 | 7.8 | 7.9 | 8.0 | 1.01 | 0.86 to 1.17 | 1.03 | 0.90 to 1.18 |

| North America other than USA and Mexico and Central America | 1270 | 66 | 5.2 | 4.3 | 8.2 | 4.5 | 1.90 | 1.09 to 3.31 | 1.04 | 0.58 to 1.86 |

| Europe | 12 546 | 568 | 4.5 | 4.3 | 5.2 | 4.3 | 1.17 | 0.96 to 1.43 | 0.97 | 0.80 to 1.17 |

| Oceania | 491 | 22 | 4.5 | 4.4 | 4.3 | 4.6 | 0.97 | 0.31 to 3.02 | 1.04 | 0.42 to 2.59 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 7380 | 513 | 7.0 | 6.7 | 7.2 | 7.1 | 1.07 | 0.87 to 1.33 | 1.05 | 0.87 to 1.28 |

| Asia (not including MENA) | 37 079 | 2285 | 6.2 | 6.1 | 6.2 | 6.3 | 1.02 | 0.92 to 1.13 | 1.04 | 0.95 to 1.14 |

| MENA+Arab+Kurd+Muslim+Sikh | 8030 | 418 | 5.2 | 4.9 | 5.4 | 5.5 | 1.08 | 0.85 to 1.39 | 1.10 | 0.89 to 1.36 |

Categories employed for maternal nativity, race/ethnicity and ancestry:

– Maternal race/ethnicity, ancestry and nativity data were reported at the time of birth by the mother. Maternal race/ethnicity was categorised using race and ancestry, categorised as White, Black, Asian/Pacific Islander and Hispanic.16 Hispanic ethnicity includes persons of Hispanic origin based on ancestry reported on the birth certificate, regardless of reported race. Black, White and Asian/Pacific Islander race categories do not include persons of Hispanic origin. For the ancestry question, mothers are able to specify the ancestry group in an open text field. Maternal nativity is categorised as born in the USA (US born) and born outside the USA. If mothers indicate that they were born outside the USA, they can specify their country of birth in a text field.

– Women who may be at risk for anti-Muslim discrimination were categorised based on ancestry and/or country of birth. The travel ban group captured any women whose reported country of birth or ancestry was included in the original seven-country travel ban (Iran, Iraq, Syria, Yemen, Sudan, Libya and Somalia). MENA group captured women whose reported country of birth or ancestry included any country belonging to the MENA region as designated by the United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner (Algeria, Bahrain, Egypt, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, Occupied Palestinian Territory, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syrian Arab Republic, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates, Yemen).17 MENA+Arab+Kurd+Muslim+Sikh group attempts to capture those women who were born in MENA countries or identified a MENA ancestry or specified an ancestry of Arab, Kurd, Muslim or Sikh (with this last group included because even though Sikhs are not Muslims, they have experienced anti-Muslim attacks on account of their appearance).18

MENA, Middle Eastern and North African; PTB, preterm birth.

Statistical analysis

PTB rates were calculated (number of preterm births×100/number of live births) city-wide and by maternal race/ethnicity, ancestry and nativity groupings. Rate ratios were calculated to determine if there was a significant change in the rates between time periods (ie, time period 3 rate/time period 1 rate). This analysis received Institutional Review Board exemption due to the use of deidentified data. Data analyses were conducted with SAS V.9.4.

Results

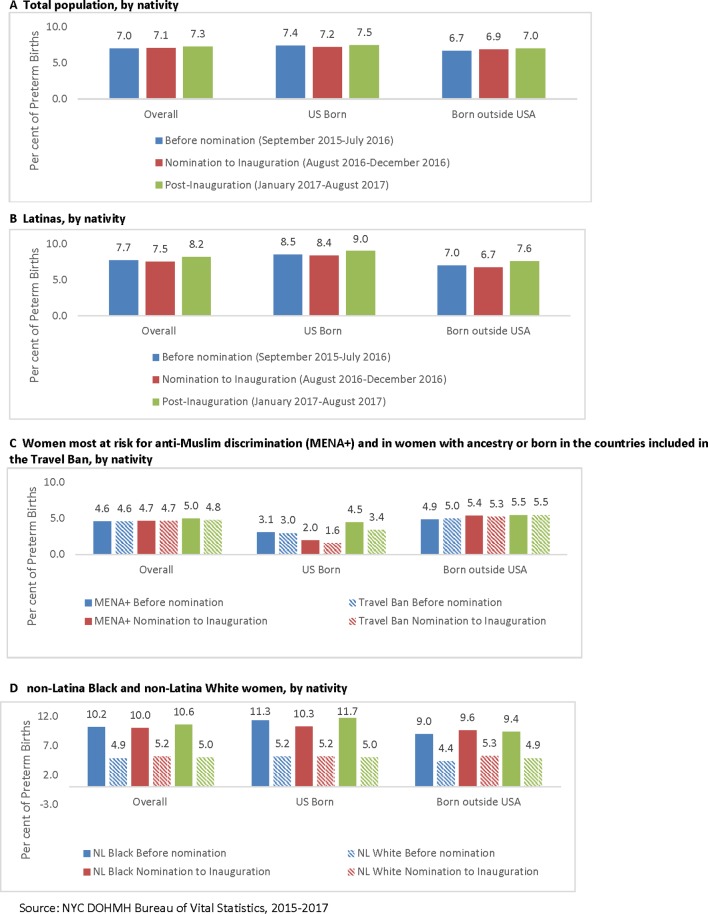

Table 1 presents the total number of births, PTBs and PTB rates during the study time periods, overall and by race/ethnicity, ancestry and nativity. Between 1 September 2015 and 31 August 2017, the overall PTB rate in NYC was 7.1% (n=230 105 births and 16 331 PTBs) (figure 1), with the highest PTB rates (≥9%) observed among the non-Hispanic Black women (US born: 11.2%; foreign born: 9.3%) and among US-born women with sub-Saharan African or Caribbean ancestry (10% and 9%, respectively).

Figure 1.

Preterm births before, during and after the 2016 US presidential election, New York City, by nativity, for: (A) total population; (B) Latinas; (C) women most at risk of anti-Muslim discrimination (MENA+) or with ancestry or born in countries included in the travel ban; and (D) non-Latina White and non-Latina Black population. MENA, Middle Eastern and North African; NL, non-Latina.

When PTB rates were compared between the period before the US presidential nomination (1 September 2015 to 31 July 2016) and post-inauguration (1 January 2017 to 31 August 2017), the overall PTB rate significantly increased from 7.0% to 7.3% (relative risk (RR)=1.04; 95% CI 1.00 to 1.07) (figure 1). Although the rate of PTB was, as expected,12 lower among mothers who were born outside the USA compared with US born in both time periods, it was only among the foreign-born mothers that the PTB rate increased (from 6.7% to 7.0%; RR: 1.06 (95% CI 1.01 to 1.11) vs no change for the US-born women: from 7.4% to 7.5%; RR: 1.02 (95% CI 0.97 to 1.07)).

Significant increases in PTB rates were especially evident for births to Hispanic women. The Hispanic PTB rate was higher post-inauguration versus pre-inauguration (RR=1.07; 95% CI 1.01 to 1.13). This pattern was driven by births to Hispanic women born outside of the USA (RR=1.08; 95% CI 0.99 to 1.17), with the increase greatest among foreign-born Hispanic women with Mexican or Central American ancestry (RR=1.15; 95% CI 1.01 to 1.31).

Non-significant post-election versus pre-election rises in PTB rates occurred among both Middle Eastern and North African women, and women affected by the travel ban, with precision of estimates limited by the small number of events. PTB rates among non-Hispanic Black women did not significantly differ across time periods, but these women consistently had the highest rates of PTB for all women, by nativity, and in each time period as compared with other women.

Conclusion

These descriptive results suggest acute increases in severe stressors, including sociopolitical stressors and hate crimes tied to the 2016 US presidential election and its aftermath,5–11 and may contribute to increases in the risk of PTB among targeted populations, particularly among Hispanic women. Although this study lacked data on potential confounders, the risk increases observed in this study are unlikely to be due to changes in other sociodemographic or medical factors, given the short time frame of observation.2–4 The impact of these acute increases in sociopolitical stressors and related rises in hate crimes, moreover, was observed in a context of persistent social inequities affecting PTB rates, as reflected by the highest rates of PTB occurring among the non-Hispanic Black women, pointing to the ongoing embodied impact of racism, via politically and socially structured material and psychosocial pathways.1 4 19

Providing context for our findings, provisional US birth data for 2017, newly released by the National Center for Health Statistics, indicated that the US PTB rate ‘rose for the third year in a row to 9.93% in 2017.’20 This rise, however, was not uniform across either weeks of gestation or race/ethnicity of the mother. Whereas the early PTB rate (<34 weeks) remained unchanged between 2016 and 2017 (at 2.76%), it increased for the late PTB rate (34–36 weeks’ completed gestation), from 7.09% in 2016 to 7.17% in 2017.20 Additionally, whereas the PTB rate, comparing 2016 to 2017, was ‘essentially unchanged among births to non-Hispanic white women (9.04% to 9.06%),’ these rates increased ‘for births to non-Hispanic blacks (13.77% to 13.92%) and Hispanic (9.45% to 9.61%) women.’20

Although a local health department has limited ability to counteract the public health impact of federal policies, the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene is committed to implementing local health strategies to protect vulnerable populations, collaborating with others to advance health equity and contributing to local and national conversation about the health impacts of adverse policies and conditions, including structural racism.19 A unique vital role going forward is to monitor PTB trends over time, as well as track federal policies that are detrimental to these populations, such as the attempts to repeal the Affordable Care Act, deportation of Deferred Action Childhood Arrivals (DACA) recipients and the enacted tax reform bill.8 10 Our PTB results, combined with national trends,20 suggest comparable activities should be carried out by additional local, state and federal health agencies, to monitor—and bring to public attention—the health impacts of political campaigns and policies that affect both population health and health inequities.

What is already known on this subject.

Robust evidence indicates risk of preterm birth (PTB; gestation <37 weeks) can be raised by exposure to severe stressors, including economic and social threats and interpersonal violence. Severe sociopolitical stressors (ie, stressors that arise from political leaders’ threatening rhetoric or from political legislation) may also elevate PTB risk. Evidence additionally indicates that in the USA, exposure to severe sociopolitical stressors for targeted racial/ethnic, immigrant and Muslim populations, and also hate crimes, has been on the rise since the fall 2015 start of the US presidential campaigns and as reflected in the policies and rhetoric of the Trump Administration, which assumed office on 20 January 2017.

What this study adds.

This is the first study to look at the impact of the most recent US presidential campaign and election on rates of PTB (gestation <37 weeks), with analysis focused on singleton births (n=230 105) in New York City for the period 1 September 2015 to 31 August 2017. The overall rise of PTB rates during this time period (from 7.0% to 7.3%; relative risk (RR) 1.04; 95% CI 1.00 to 1.07) was most pronounced for post-inauguration versus pre-inauguration period births among Hispanic women with Mexican or Central American ancestry who were born outside of the USA (RR=1.15; 95% CI 1.01 to 1.31). The results suggest changes in the severity of sociopolitical stressors may be adversely impacting health of the targeted populations and these health impacts warrant public health monitoring.

Footnotes

Contributors: NK conceived the study and led writing of the manuscript. NK, PDW, MH, WL and GVW jointly designed the study’s analytic approach. PDW created the ICE variable. MH, WL and GVW accessed, cleaned and categorised the NYC DOHMH data. MH and WL ran the statistical analysis. NK, PDW, MH, WL and GVW interpreted the results. All authors provided critical feedback on the manuscript and reviewed and approved the final version prior to submission.

Funding: This work was supported by the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study was approved as exempt by both the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health IRB (protocol IRB15-2304; 25 June 2015) and the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene IRB (protocol 18-053; 23 April 2018).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data can be obtained only from the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, following their protocols for data sharing.

References

- 1. Alhusen JL, Bower KM, Epstein E, et al. . Racial discrimination and adverse birth outcomes: an integrative review. J Midwifery Womens Health 2016;61:707–20. 10.1111/jmwh.12490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Eskenazi B, Marks AR, Catalano R, et al. . Low birthweight in New York City and upstate New York following the events of September 11th. Hum Reprod 2007;22:3013–20. 10.1093/humrep/dem301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Novak NL, Geronimus AT, Martinez-Cardoso AM. Change in birth outcomes among infants born to Latina mothers after a major immigration raid. Int J Epidemiol 2017;46:839–49. 10.1093/ije/dyw346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mutambudzi M, Meyer JD, Reisine S, et al. . A review of recent literature on materialist and psychosocial models for racial and ethnic disparities in birth outcomes in the US, 2000-2014. Ethn Health 2017;22:311–32. 10.1080/13557858.2016.1247150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Philbin MM, Flake M, Hatzenbuehler ML, et al. . State-level immigration and immigrant-focused policies as drivers of Latino health disparities in the United States. Soc Sci Med 2018;199:29–38. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Artiga S, Ubri P, 2017. Living in an immigrant family in america: how fear and toxic stress are affecting daily life, well-being, & health. Kaiser Family Foundation issue brief https://www.blueshieldcafoundation.org/sites/default/files/covers/Issue-Brief-Living-in-an-Immigrant-Family-in-America.pdf (accessed 18 Jul 2018).

- 7. Nichols VC, LeBrón AMW, Pedraza FI. Policing us sick: the health of latinos in an era of heightened deportations and racialized policing. PS 2018;51:293–7. 10.1017/S1049096517002384 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Williams DR, Medlock MM. Health effects of dramatic societal events - ramifications of the recent presidential election. N Engl J Med 2017;376:2295–9. 10.1056/NEJMms1702111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. AOL.com, 2016. Presidential campaign timeline https://www.aol.com/2016-election/timeline/ (accessed 18 Jul 2018).

- 10. AOL.com. Timeline: Trump’s first 100 days. https://www.aol.com/news/trump-first-100-days/ (accessed 18 Jul 2018).

- 11. Levin B, Nolan JJ, Reitzel JD. Crimesider/CBS News. New data shows hate crimes continued to rise in 2017. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/new-data-shows-us-hate-crimes-continued-to-rise-in-2017/ (accessed 18 Jul 2018).

- 12. Villalonga-Olives E, Kawachi I, von Steinbüchel N. Pregnancy and birth outcomes among immigrant women in the US and Europe: a systematic review. J Immigr Minor Health 2017;19:1469–87. 10.1007/s10903-016-0483-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Berenson T, 2015. Donald Trump calls for ‘complete shutdown’ of Muslim entries to US http://time.com/4139476/donale-trum-shutdown-muslin-immigration/ (accessed 18 Jul 2018).

- 14. Finnegan M, Barabak M. Los Angeles Times, 2018. ‘Shithole’ and other racist things Trump has said – so far http://www.latimes.com/politics/la-na-trump-racism-remarks-20180111-htmlstory.html (accessed 18 Jul 2018).

- 15. Collins E. USA Today. The Trump-Kahn Feud: how we got here. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/onpolitics/2016/08/01/trump-kahn-feud-timeline/87914108 (accessed 18 Jul 2018).

- 16. Office of Management and Budget. Revisions to the standards for the classification of federal data on race and ethnicity. Federal Registrar 1997;62:58782–90. [Google Scholar]

- 17. United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner. MENA Region (Middle Eastern and Northern Africa Region). http://www.ohchr.org/EN/Countries/MenaRegion/Pages/MenaRegionIndex.aspx (accessed 19 May 2018).

- 18. Suri M, Wu H. CNN News. Sikhs: religious minority target of hate crimes. https://www.cnn.com/2017/03/06/asia/sikh-hate-crimes-us-muslims/index.html (accessed 18 Jul 2018).

- 19. Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, et al. . Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet 2017;389:1453–63. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Osterman MJK, et al. . Births: Provisional data for 2017. Vital Statistics Rapid Release. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/vsrr/report004.pdf (accessed 18 Jul 2018). [Google Scholar]