Abstract

Objective

To understand the gender-specific factors that uniquely contribute to successful ageing in a US population of men and women, 57–85 years of age. This was achieved through the examination of the correlates of subjective well-being defined by health-related quality of life (HRQoL), across several biological and psychosocial determinants of health.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

The National Social Life, Health and Ageing Project (NSHAP), 2010–2011 a representative sample of the US population.

Participants

3377 adults aged 57–85 (1538 men, 1839 women) from the NSHAP.

Main outcome measures

The biopsychosocial factors of biological/physiological function, symptom status, functional status, general health perceptions and HRQoL happiness.

Method

HRQoL was measured using the NSHAP wave 2 multistage, stratified area probability sample of US households (n=3377). Variable selection was guided by the Wilson and Cleary model (WCM) that classifies health outcomes at five main levels and characteristics.

Results

Our findings indicate differences in biopsychosocial factors comprised in the WCM and their relative importance and unique impact on HRQoL by gender. Women reported significantly lower HRQoL than men (t=3.5, df=3366). The most significant contributors to HRQoL in women were mental health (B=0.31; 0.22, 0.39), loneliness (B=−0.26; −0.35, –0.17), urinary incontinence (B=−0.22; −0.40, –0.05) and support from spouse/partner (B=0.27; 0.10, 0.43) and family B=0.12; 0.03, 0.20). Men indicated mental health (B=0.21; 0.14, 0.29), physical health (B=0.17; 0.10, 0.23), functional difficulties (B=0.38; 0.10, 0.65), loneliness (B=−0.20; −0.26, –0.12), depression (B=−0.36; −0.58, –0.15) and support from friends (B=0.06; 0.10, 0.11) as significant contributors. Those with greater social support had better HRQoL (F=4.22, df=4). Lack of companionship and reliance on spouse/partner were significant HRQoL contributors in both groups.

Conclusion

Our findings offer insight into ageing, gender and subjective well-being. The results provide an opportunity to identify biopsychosocial factors to inform interventions to support successful ageing.

Keywords: aging, well-being, gender differences, health-related quality of life

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A variety of biopsychosocial factors that contribute to well-being by gender were compared, where prior studies have not used gender as an independent variable.

Effect sizes were used to summarise our regression analyses for a manageable and clinically interpretable picture of the unique contribution of gender across the comprehensive Wilson and Cleary model (WCM), linking biopsychosocial factors to overall well-being defined as health-related quality of life (HRQoL) happiness.

We were unable to establishing a cause–effect relationship or to determine changes in perceptions over time based on our cross-sectional analysis.

We were limited to define the WCM levels based on variables in the National Social Life, Health and Aging Project (NSHAP); yet with the variety of indicators captured in the NSHAP, this was a minor limitation.

Beyond identified limitations, results mirrored prior research and contributed to the understanding of HRQoL gender-based differences, while controlling for potential confounders including age, race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status.

Introduction

Successful ageing was traditionally defined as the absence of disease and associated functional limitations.1 However, the definition has shifted to a multidimensional view that accounts for psychosocial and cultural aspects of health and health-related quality of life (HRQoL).1 2 This shift in definition is driven by patient-centred care, patient empowerment and shared decision-making with providers in the healthcare setting.2 In fact, HRQoL is now viewed as an important complement to biomedical measures of health.3 An important indicator of successful ageing is subjective well-being, an aspect of HRQoL. Subjective well-being is a direct predictor of health outcomes affecting biological, physical and psychosocial changes in older adults.4 5 Improvement in population-level well-being is an aspiration of society, sparking policy and economic debates.6 Studies of life satisfaction have shown that subjective well-being is affected by a multitude of additional factors, including social and familial relationships. These additional factors may be protective, potentially decreasing or eliminating the chronic disease and symptom burden.6

Three approaches exist to capture subjective well-being; these are life evaluation (eg, life satisfaction); hedonic well-being (eg, experienced happiness, anger) and eudemonic well-being (eg, life meaning and purpose.6 Researchers suggest subjective well-being as a measure for healthcare resources allocation. Therefore, the need exists to further identify and understand the factors associated with successful ageing.2 7 It is also essential to compare these factors between men and women to determine the unique contribution of gender.2 Evidence to date remains unclear as prior studies of gender differences have focused on specific chronic diseases or on socioeconomic and demographic factors, usually controlling for gender as a potential confounder and not as an independent variable.8 Therefore, we sought to identify the correlates and aetiological factors associated with hedonic well-being, specifically feelings of happiness, through a biopsychosocial lens, accounting for gender variability, in an ageing population of US adults. Happiness served as a proxy for HRQoL. It is a measure of life satisfaction, the absence or presence of desirable or undesirable feelings or experiences. It is proven useful in the analysis of HRQoL.9

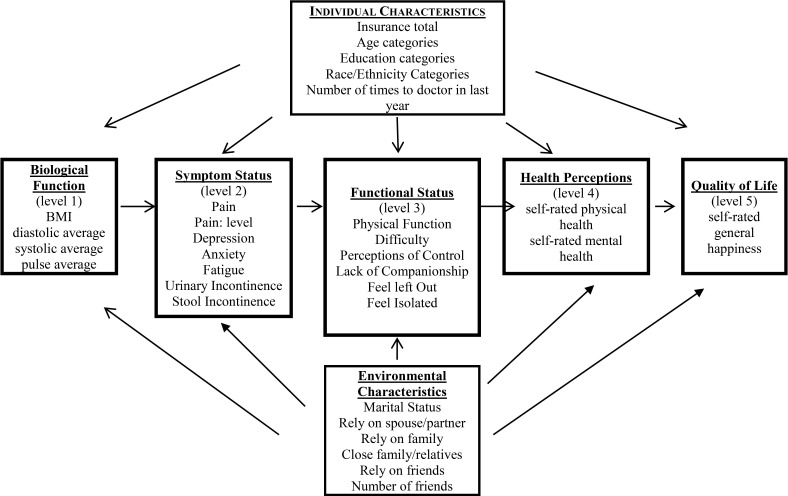

Guided by the Wilson and Cleary conceptual model (WCM) figure 1, we analysed the National Social Life, Health and Aging Project (NSHAP), second wave data. We examined whether objective (eg, biological/physiological) and self-perceived measures (eg, functional status) of health explain gender differences in HRQoL (ie, happiness). Self-rated perceptions of health have been observed to correlate with other health indicators including morbidity.10 We determined the models predicting the HRQoL of male and female US adults ages 57–85.11 We explored the extent to which the WCM levels interact to predict HRQoL and provide greater insight into ageing. The biopsychosocial WCM was selected for our analysis as it considers health outcomes on a continuum of increasing complexity and health trajectories associated with ageing. It is also shown to enhance knowledge about HRQoL in diverse populations.11 The model classifies health outcomes at five main levels.11 The first level biological/physiological function examines the individual as a whole. Symptoms (level 2) are the perceptions of physical, emotional and cognitive states. Symptoms are considered significant determinants of functional status (level 3), with biological and symptom variables evidenced to be correlated with functional status. General health perceptions (level 4) are subjective appraisals of health and overall quality of life (level 5) as a whole.11 Variables that comprise each level interact in complex ways to determine HRQoL. Arrows linking the five main levels indicate dominant causal relationships. In addition, the five main levels are influenced by individual (eg, age, education) and environmental characteristics (eg, social support).11 Studies of hedonic states, including happiness, have predicted morbidity and mortality. However, confounding factors indicate that well-being is coupled with additional factors such as education.10 The WCM controls for potential confounding. Additionally, different than prior studies that compared the quantified HRQoL scores across gender, we identified the hierarchical differences of each WCM level and their weighted contribution to HRQoL (happiness).

Figure 1.

Operationalised Wilson and Cleary model with study-specific biopsychosocial measures. BMI, body mass index.

Methods

Participants

The second wave of the NSHAP survey, a national sample of US adults ages 57–85, was used in our analysis, was conducted from 2010 to 2011.12 The survey focused on exploring interpersonal connections and overall health outcomes as they relate to: culture, gender and socioeconomic status; health behaviours; healthcare utilisation, social support and well-being.12 Our current study used wave 2 data to explore the relationship between the WCM constructs for both men and women. Wave 2, with its large sample size (n=3377) and strong methodology, allowed us to systematically investigate important aspects of HRQoL and ageing.

Measures

NSHAP variables used in our analysis were selected based on best fit with the WCM constructs. Thirty variables were selected. We categorised the five main levels and characteristics of the WCM under two overarching categories of objective and subjective health indicators, figure 1. The objective indicators of the first main level of biological/physiological function were categorical: body mass index and continuous: average pulse rate and average blood pressure (systolic and diastolic). The last four main levels of the WCM comprised subjective health indicators. These included the assessment of participant perceptions of health outcomes on both individual and societal levels. Variables that comprised symptom status were categorical: pain, pain level, fatigue, urinary incontinence, stool incontinence and continuous: depression, anxiety. Variables that comprised functional status were categorical: physical function difficulty, companionship and feeling left out or isolated and continuous: perceptions of control. Variables that comprised general health perceptions were continuous self-rated physical and mental health.

Our continuous outcome variable of interest for HRQoL in this study was defined by hedonic well-being: self-rated happiness, asked participants thoughts and feelings about their life overall. The WCM also accounts for important individual and environment influences directly impacting objective and subjective indicators. Variables that comprise individual characteristics were categorical: insurance coverage, age group, education, race/ethnicity and provider visits. Variables that comprise environmental characteristics were categorical: marital status, reliance on spouse/partner, relatives and friends, and number of close family/relatives and friends.

Statistical analysis

The association between HRQoL (ie, happiness) and the constructs of the WCM were examined in separate analyses for male and female participants. Descriptive statistics were conducted to characterise the sample and variable distributions. Participant characteristics were summarised with means and SDs for continuous variables and percentages and frequencies for categorical variables. Individual and environmental characteristics were also examined for potential confounding. Correlations were calculated to determine the relationship between the WCM construct and characteristic variables and reported HRQoL by participants. Bivariate analysis was conducted. X2 analyses were used to assess differences in categorical variables and t-tests in continuous variables, by gender. Linear regression analyses were performed to assess the relevant importance of significantly correlated variables that potentially contribute to HRQoL. For model validation, our dataset was randomly divided, using a split-sample technique, into a developmental: n=1689 and validation: n=1688 group before identifying final model variables.13 The development model was selected through a stepwise multiple regression to identify the model of best fit. To determine the accuracy of the developmental model, a regression model was calculated with the validation dataset for the retained variables. To choose the final model, adjusted R2 values, Standardised βs and unstandardised slopes (B) were observed between the developmental and validation models to ensure analytical comparability. Variables with significant differences (p<0.05) were retained for additional analysis.

Two independent stepwise multiple regressions were then performed based on gender (ie, men and women) to identify variables, by gender, best associated with HRQoL. Retained variables were ranked by partial R2 order to determine their relative contribution. Effect sizes were also estimated for each retained variable with t values corresponding to the coefficient estimates divided by the associated standard errors. To identify constructs with the most consistent associations with HRQoL, effect sizes and R2 rankings were averaged per WCM construct for men and women. Data analysis was conducted with use of SPSS V.22.0. The stepwise approach allows for the prevention of bias in the selection of variables in the final model.14 15

Patient involvement

As an analysis of secondary data, no participants were not involved in the development of our research questions or with the analysis of the outcome measures. Additionally, participants were not involved with the interpretation of data or the writing of our analytical findings. Dissemination of analytical findings to study participants or members of their associated communities will not be accomplished.

Results

A total of 3377 participants were included in the analysis. The majority of participants (54.5%) were women. The largest percentage of men were in the 70–79 age group (39.7%) with the largest percentage of women in the 69 and under age group (44.2%). The sample was predominantly non-black, non-Hispanic (73.8%, n=2493). Most participants had at least a high school education (56.2%, n=1899). More than two-thirds were married (67.7%, n=2286). Of those who indicated they were unmarried, 88.5% (n=890) were not in any romantic, intimate or sexual partnerships. More than two-thirds had healthcare coverage in the form of Medicaid, Medicare or a combination of both (81.3%, n=2307). Tables 1 and 2 provide a breakdown of the demographic characteristics and significant differences for variables that comprise the WCM constructs for men and women. Table 3 describes the baseline characteristics of the development and validation cohorts.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants (n=3377)

| N | (%) | |

| Gender | ||

| Men | 1538 | 45.5 |

| 69 or under | 585 | 38.0 |

| 70–79 | 610 | 39.7 |

| 80 or older | 343 | 22.3 |

| Women | 1839 | 54.5 |

| 69 or under | 812 | 44.2 |

| 70–79 | 633 | 34.4 |

| 80 or older | 394 | 21.4 |

| Race | ||

| Men | ||

| Non-black, non-Hispanic | 1147 | 74.6 |

| Black or African-American | 217 | 14.1 |

| Non-black Hispanics | 174 | 11.3 |

| Women | ||

| Non-black, non-Hispanic | 1346 | 73.2 |

| Black or African-American | 300 | 16.3 |

| Non-black Hispanics | 193 | 10.5 |

| Education | ||

| Men | ||

| More than high school | 884 | 57.5 |

| High school or less | 654 | 42.5 |

| Women | ||

| More than high school | 1015 | 55.2 |

| High School or less | 824 | 44.8 |

| Insurance coverage | ||

| Men | ||

| Medicaid–Medicare | 1080 | 83.9 |

| Private | 161 | 12.5 |

| None | 46 | 3.6 |

| Women | ||

| Medicaid–Medicare | 1227 | 79.1 |

| Private | 250 | 16.1 |

| None | 75 | 4.8 |

| Marital status | ||

| Men | ||

| Married | 1201 | 78.1 |

| Not currently married | 337 | 21.9 |

| Women | ||

| Married | 1085 | 59.0 |

| Not currently married | 754 | 41.0 |

| Partnership if non-married | ||

| Men | ||

| No | 231 | 77.5 |

| Women | ||

| No | 659 | 93.1 |

Table 2.

Independent samples t-tests and X2 for Wilson and Cleary model construct-specific variables with men and women (n=3377)

| Men | Women | X2/t-test | df | |

| Biological/physiological function | ||||

| BMI (normal) | 36.5% | 63.5% | 29.0** | 2 |

| Diastolic average | 79.0±12.0 | 81.0±11.5 | −6.4** | 3255 |

| Systolic average | 138.0±0.20.7 | 137.0±21.0 | 1.6 | 3255 |

| Pulse average | 67.7±12.1 | 69.8±11.2 | −5.1** | 3035 |

| Symptom status | ||||

| Pain | 43.8% | 56.2% | 8.9** | 1 |

| Pain: level (no pain) | 50.0% | 50.0% | 11.2 | 6 |

| Depression (CESD total)† | 1.8±0.3 | 2.0±0.4 | −6.6** | 3312 |

| Anxiety (HADS total)† | 1.8±0.5 | 1.8±0.4 | −0.8 | 2627 |

| Fatigue | 54.7% | 45.3% | 3.1 | 3 |

| Urinary incontinence† | 30.2% | 69.8% | 94.7** | 1 |

| Stool incontinence | 30.4% | 69.6% | 15.5** | 1 |

| Functional status | ||||

| No physical function difficulty† | 46.1% | 53.9% | 27.1 | 16 |

| Perceptions of control | 2.3±0.5 | 2.2±0.6 | 2.7** | 2665 |

| Companionship | 49.8% | 50.2% | 21.0** | 3 |

| Feel left out | 54.0% | 46.0% | 3.1 | 3 |

| Feel isolated | 55.8% | 44.2% | 1.5 | 3 |

| General health perceptions | ||||

| Self-rated physical health† | 3.2±1.1 | 3.2±1.0 | −0.7 | 3370 |

| Self-rated mental health† | 3.7±1.0 | 3.6±1.0 | 3.2** | 3372 |

| Individual characteristics | ||||

| Insurance | 96.4% | 95.2% | 10.95** | 1 |

| Age category (≥70) | 62% | 55.8% | 14.1** | 1 |

| Education (> high school) | 57.5% | 55.2% | 1.78 | 1 |

| Race/ethnicity (non-black non-Hispanic) | 74.6% | 73.2% | 3.39 | 1 |

| Seen the doctor in last year† | 3.0±1.5 | 3.04±1.5 | −1.28 | 3367 |

| Environmental characteristics | ||||

| Rely on family | 36.9% | 63.1% | 42.14** | 3 |

| Has close family/relatives† | 38.6% | 61.4% | 52.05** | 5 |

| Rely on friends | 44.3% | 55.7% | 71.78** | 3 |

| Has friends† | 44.9% | 55.1% | 13.12* | 5 |

| Rely on spouse/partner† | 63.3% | 36.70% | 26.92** | 3 |

*P<0.05, **P<0.01.

†Variables that comprise the validated regression model and retained for subsequent gender-related regression analysis.

BMI, body mass index; CESD, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the developmental and validation models Wilson and Cleary model construct-specific variables

| Construct-specific variables | Developmental cohort (n=1689) | Validation cohort (n=1688) | |||||

| Descriptives | β | 95% CI | Descriptives | β | 95% CI | ||

| Symptom status | Depression (CESD total) | 1.9 ±0.34 | −0.111* | −0.537 to −0.061 | 1.9 ±0.35 | −0.099** | −0.447 to −0.094 |

| Anxiety (HADS total) | 1.8 ±0.45 | −0.201** | −0.499 to −0.291 | 1.8 ±0.45 | −0.212** | −0.563 to −0.270 | |

| Urinary incontinence | 0.42 | −0.070* | −0.112 to 0.076 | 0.43 | −0.059* | −0.238 to 0.028 | |

| Functional status | No physical function difficulty | 0.72 | −0.102** | −0.288 to −0.118 | 0.72 | −0.107** | −0.181 to −0.045 |

| Companionship | 0.39 | −0.168** | −0.238 to −0.075 | 0.40 | −0.166** | −0.207 to −0.129 | |

| Feel isolated | 0.27 | −0.146** | −0.240 to −0.060 | 0.26 | −0.148** | −0.229 to −0.113 | |

| General health perceptions | Self-rated physical health | 3.22±1.05 | 0.121* | 0.021 to 0.175 | 3.19±1.07 | 0.123** | 0.061 to 0. 110 |

| Self-rated mental health | 3.62 ±0.96 | 0.244** | 0.126 to 0.283 | 3.62 ±0.99 | 0.240** | 0.153 to 0.272 | |

| Individual characteristics | Education (>high school) | 0.58 | 0.074* | −0.003 to 0.281 | 0.58 | 0.068* | −0.025 to 0.180 |

| Seen the doctor in last year | 3.06±1.5 | −0.099** | −0.093 to −0.027 | 2.97±1.5 | −0.105** | −0.081 to −0.042 | |

| Environmental characteristics | Has close family/relatives | 0.98 | 0.122** | 0.059 to 0.150 | 0.98 | 0.123** | 0.061 to 0.110 |

| Has friends | 0.97 | 0.079* | −0.001 to 0.105 | 0.97 | 0.066* | −0.010 to 0.136 | |

| Rely on spouse/partner | 0.96 | 0.130** | 0.094 to 0.357 | 0.97 | 0.134* | 0.138 to 0.330 | |

*P<0.05, **P<0.01.

CESD, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

Bivariate correlation analyses were initially conducted to examine the associations between the outcome HRQoL variable and those that comprised the WCM constructs. For men, of the original 30 variables, bivariate correlation analysis led to the elimination of six variables (24 remaining), for women the elimination of seven variables (23 remaining). All significantly correlated variables that comprised the WCM constructs and characteristics were then validated by linear regression, reducing the variable list from 24 to 13 (table 2), for final model development by gender. HRQoL happiness scores were compared by the total scores for men, women and participants combined across the categorised age groups (69 or younger, 70–79, 80 or older). Significant results were observed across age groups for combined participants (X2=18.6, p=0.017) and for women (X2=20.1, p=0.010), both having significantly lower HRQoL score with increasing age.

Separate linear regression analyses were conducted for men and women. Partial R2 were ranked from 1 (most important) to 5 (least important) for men and women separately, with significant variables identified. Additionally, the last two columns on table 4 contain the average of the R2 ranking and the average effect sizes. The highest ranking variable for overall HRQoL happiness for men was general health perceptions (self-rated: mental health and physical health), symptom status (Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CESD) score) and functional status (lack companionship) both ranked second based on R2 ranks, with symptom status having a greater average effect size. Physical function difficulty and environmental characteristics (rely on spouse/partner) were last. Our regression analyses identified variables that, in the presence of all others, make a unique and direct contribution to HRQoL happiness.10 The highest ranking variable for overall HRQoL for women was general health perceptions (mental health), followed by functional status (lack of companionship), environmental characteristics (rely on spouse/partner and number of close family members) and symptom status (urinary incontinence). The hierarchy of contributing WCM constructs to overall HRQoL are ranked for men and women, table 5.

Table 4.

Wilson and Cleary Model constructs and health-related quality of life outcomes

| Partial R2 | Partial R2 rank | Effect size (t values) |

Average R2 ranks | Average effect sizes (t values) | |

| Men | |||||

| General health perceptions | 0.24, 1.8 | 1, 3 | 8.3, 5.9 | 2 | 7.1 |

| Functional status | 0.21, 0.07 | 2, 6 | 7.2, 2.2 | 4 | 4.7 |

| Symptom status | 0.14 | 4 | 4.8 | 4 | 4.8 |

| Environmental characteristics | 0.09 | 5 | 3.0 | 5 | 3.0 |

| Women | |||||

| General health perceptions | 0.39 | 1 | 9.4 | 1 | 9.4 |

| Functional status | 0.33 | 2 | 7.9 | 2 | 7.9 |

| Symptom status | 0.03 | 5 | 0.68 | 5 | 0.68 |

| Environmental characteristics | 0.16, 0.12 | 3, 4 | 3.6, 2.6 | 3.5 | 3.09 |

Table 5.

Hierarchy of health-related quality of life contributors based on average effect sizes

| Rank | Item descriptions | |

| Men | ||

| 1st | General health perceptions | Self-rated: mental health and physical health |

| 2nd | Symptom status | Depression |

| 3rd | Functional status | Lack companionship, physical function difficulty |

| 4th | Environmental characteristics | No of close friends |

| Women | ||

| 1st | General health perceptions | Self-rated: mental health |

| 2nd | Functional status | Lack companionship |

| 3rd | Environmental characteristics | Rely on spouse/partner and no of close family |

| 4th | Symptom status | Urinary incontinence |

Discussion

Understanding subjective well-being and its association with health in older adults is still in its early stages. Consequently, the extent to which a variety of biopsychosocial factors attribute to well-being and account for gender-related differences remain unclear. To explore this further, we used the WCM which offers the most comprehensive view of pathways linking the most relevant biopsychosocial variables to overall well-being defined as HRQoL happiness.2 11 16 17 Epidemiological studies of happiness have predicted long-term morbidity and mortality. Previous studies have shown that subjective well-being is not universal across populations, yet individual characteristics including, education and race/ethnicity, did not significantly contribute to HRQoL happiness in our population.10 Our results did, however, identify significant differences between men and women in the type and contribution of biopsychosocial factors to HRQoL happiness. The overall models allowed for us to observe the interplay between various aspects of ageing by gender.11

Mechanisms and implications

Women reported significantly lower HRQoL than men. Our findings also indicated a significant decrease in HRQoL as age increased for the entire sample and for women. A decrease in HRQoL was also observed for men, but the results were not significant. Previous studies have identified lower HRQoL in populations of older women. It is hypothesised that gender-related differences in HRQoL of older adults may be in their perceptions of symptoms and illness progression, with men being less focused on symptom recognition until they are severe.8 Interestingly, although there were no significant differences in perceptions of physical health between men and women in our analysis, it was the greatest contributor of HRQoL in men. Similarly, the third greatest contributor to HRQoL in men was the functional status level factor physical function difficulty, also not observed in women. Prior studies have indicated that functional difficulty generally comprise the majority of an individual’s functional health status, which in our study again was only associated with men. This is an interesting finding and may be attributed to the increased likelihood of men suffering from more severe and life-threatening chronic conditions than women.8 Instead, women are more likely to suffer from non-life-threatening diseases including autoimmune disorders.8 Social support significantly contributed to HRQoL in both men and women. The lack of companionship under the functional status level was significant in both groups. These findings align with the literature on loneliness in older ages and its adverse effects on HRQoL.18 19 The reduction of intergenerational living and greater geographical expansion has increased the report of loneliness in populations of older adults. Loneliness directly increases the likelihood of chronic diseases and all-cause mortality.18 19 In our sample, the number of close family members was seen a significant contributor to HRQoL for women only. Having close family members may be more important to women, with 41% of the female sample reported being unmarried, only 21.9% of men. Additionally, HRQoL scores were significantly higher for married women. For those who reported being unmarried with a romantic, intimate or sexual partner, men were significantly higher at 22.5% and women at 6.9%. Participants who reported greater social support from partners and relatives had higher HRQoL. Unhealthy familial relationships were predictors of loneliness in a prior study, particularly for the unmarried.18 19 Their findings identify family ties as the most significant contributor to loneliness.18 19 This aligns with our findings as women who reported a greater number of reliable family members had significantly higher HRQoL scores. Therefore, the need exists for the consideration of social networks20 21 and their impact on HRQoL in risk assessment and intervention development to improve ageing-related outcomes. Previous studies have also shown that men and women who were satisfied with their family relationship had 1.8 and 3.0 times higher odds of good HRQoL, respectively. Frequent contacts and visits with friends or family motivate the participation in activities and increase HRQoL.21 22

The highest level significant contributor to HRQoL in both men and women was the general health perceptions level which both comprised mental health. In fact, those who reported better mental health outcomes reported higher HRQoL. Men reported better mental health at a significantly higher level than women. Yet, depression was the only significant factor for the symptom status level in men alone and was the second highest contributor to their HRQoL. Other studies have shown that mental health concerns and symptoms of depression significantly impact HRQoL.2 11 23 Our findings align with the literature on depression, with depression in women reported to be higher.2 11 16 24–28 In fact, in our sample, depression scores for women were significantly higher than for men. Yet, depression was a major contributor to HRQoL only in men. Studies have shown that unmarried men have lower HRQoL compared with married men. Our findings show significantly higher depression scores for married men in our sample. Those who reported having demanding or critical spouses or did not spend much time with their spouses had significantly higher depression scores. Though not significant in the hierarchical model, women with demanding and critical spouses also reported significantly higher depression scores. These results further reinforce our findings that relationship quality is a major contributor to HRQoL. Urinary incontinence was the only significant factor in the symptom status level for women. Those with urinary incontinence had significantly lower HRQoL scores. Our findings align with the literature, with recent studies indicating that women were more likely to report urinary incontinence and impaired HRQoL.29 30 Additionally, pelvic organ prolapse (POP), which often peaks for women in their seventies, include the symptoms of urinary incontinence. Studies have shown significantly impaired quality for women with POP over the age of 50.31 Symptomatic POP is evidenced to have a tremendous impact on general HRQoL and similar to disabilities, it can contribute to physical immobility, pain, diminished energy, sleep disturbance, emotional instability and social isolation.31 Studies have also shown that self-image is considered to be more important to women than men. In fact, in a study comparing HRQoL indicators between older men and women, a positive attitude about oneself was ranked in the top 10 only for women.32 33 Urinary incontinence may impact self-image, increasing the likelihood of depression and social isolation. Our findings indicate women who report urinary incontinence had significantly higher depression scores; consistent with the higher likelihood of depression and anxiety disorders in women compared with men.8

Strengths and limitations

Our analysis was based on a cross-sectional, single wave (wave 2) of the NSHAP data and does not allow for establishing a cause–effect relationship or the determination of changes in perceptions over time. Our analysis is also limited to define the WCM levels based on variables included in the NSHAP, a limitation inherent to secondary data analysis. However, with the variety of indicators that comprise the NSHAP, this was a minor limitation.

Variables that may indirectly impact HRQoL are not identified, yet our analytical approach provides a minimum collection of variables necessary to begin the development of structural equation models to observe directional relationships. In fact, our regression approach identified the variables that make a distinct and direct contribution to HRQoL. Furthermore, our model validation increased our confidence in the predictive validity of the models.

HRQoL was measured with one item of self-reported happiness in the NSHAP. Our single item analysis may be considered less sensitive than the use of other HRQoL measures or validated tools. Yet, beyond the identified limitations, our study findings mirrored and reinforce prior research and further contributed to understanding HRQoL differences between older men and women while adjusting for confounders including age, race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status.

Conclusions and implications

The current analysis provides additional evidence to support insight into subjective well-being as it relates to successful ageing. The findings of our analysis enhance our understanding of the biopsychosocial factors that impact the HRQoL of older men and women. Our results add to the literature on successful ageing in addition to the utility of the WCM in understanding the impact of HRQoL based on a variety of associated factors that comprise the models levels. We observed both similarities and differences between men and women based on the levels that best contribute to HRQoL. Further investigation is needed to determine the causal factors of the identified relationships between WCM levels and HRQoL. Other indicators of subjective well-being (eg, life evaluations and eudemonic well-being) must also be assessed for collaborative care informed by mental and physical health.10 In addition to informing the development of effective interventions to improve well-being independent of morbidity, income and other ageing related factors that have adversely contributed to poor health outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: The first author (MO) designed the work and analysed the data. All authors assisted substantially in the data interpretation (MO, ND, OO, MP and RB), manuscript drafting (MO), revising for important intellectual content (MO, ND, OO, MP, RB and DB), final manuscript approval (MO, ND, OO, MP, RB and DB) and agreed accountability for all aspects of this work (MO, ND, OO, MP, RB and DB).

Funding: The National Social Life, Health and Aging Project is supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health (R37AG030481; R01AG033903).

Disclaimer: The content is the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Wave 2 Public Use File V.1 data for the National Social Life Health and Aging Project are available at http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/NACDA/studies/34921.

References

- 1. Topaz M, Troutman-Jordan M, MacKenzie M. Construction, deconstruction, and reconstruction: The roots of successful aging theories. Nurs Sci Q 2014;27:226–33. 10.1177/0894318414534484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zubritsky C, Abbott KM, Hirschman KB, et al. . Health-related quality of life: expanding a conceptual framework to include older adults who receive long-term services and supports. Gerontologist 2013;53:205–10. 10.1093/geront/gns093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Haraldstad K, Rohde G, Stea TH, et al. . Changes in health-related quality of life in elderly men after 12 weeks of strength training. Eur Rev Aging Phys Act 2017;14:8 10.1186/s11556-017-0177-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chambers LA, Wilson MG, Rueda S, et al. . Evidence informing the intersection of HIV, aging and health: a scoping review. AIDS Behav 2014;18:661–75. 10.1007/s10461-013-0627-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lim JW, Gonzalez P, Wang-Letzkus MF, et al. . Understanding the cultural health belief model influencing health behaviors and health-related quality of life between Latina and Asian-American breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 2009;17:1137–47. 10.1007/s00520-008-0547-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Banerjee S. Multimorbidity-older adults need health care that can count past one. Lancet 2015;385:587–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61596-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. López-Otín C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, et al. . The hallmarks of aging. Cell 2013;153:1194–217. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cherepanov D, Palta M, Fryback DG, et al. . Gender differences in health-related quality-of-life are partly explained by sociodemographic and socioeconomic variation between adult men and women in the US: evidence from four US nationally representative data sets. Qual Life Res 2010;19:1115–24. 10.1007/s11136-010-9673-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Michalos AC. Social Indicators Research and Health-Related Quality of Life Research Connecting the Quality of Life Theory to Health, Well-being and Education: The Selected Works of Alex C. Michalos Cham: Springer International Publishing: The Selected Works of Alex C, 2017:25–58. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Steptoe A, Deaton A, Stone AA. Subjective wellbeing, health, and ageing. The Lancet 2015;385:640–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61489-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sousa KH, Kwok OM. Putting Wilson and Cleary to the test: analysis of a HRQOL conceptual model using structural equation modeling. Qual Life Res 2006;15:725–37. 10.1007/s11136-005-3975-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Waite LJ, Laumann EO, Das A, et al. . Sexuality: measures of partnerships, practices, attitudes, and problems in the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2009;64 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):i56–i66. 10.1093/geronb/gbp038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Han K, Song K, Choi BW. How to develop, validate, and compare clinical prediction models involving radiological parameters: Study design and statistical methods. Korean J Radiol 2016;17:339–50. 10.3348/kjr.2016.17.3.339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rodríguez AM, Mayo NE, Gagnon B. Independent contributors to overall quality of life in people with advanced cancer. Br J Cancer 2013;108:1790–800. 10.1038/bjc.2013.146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schildcrout JS, Basford MA, Pulley JM, et al. . An analytical approach to characterize morbidity profile dissimilarity between distinct cohorts using electronic medical records. J Biomed Inform 2010;43:914–23. 10.1016/j.jbi.2010.07.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shiu AT, Choi KC, Lee DT, et al. . Application of a health-related quality of life conceptual model in community-dwelling older Chinese people with diabetes to understand the relationships among clinical and psychological outcomes. J Diabetes Investig 2014;5:677–86. 10.1111/jdi.12198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rizzo VM, Kintner E. Understanding the impact of racial self-identification on perceptions of health-related quality of life: a multi-group analysis. Qual Life Res 2013;22:2105–12. 10.1007/s11136-013-0349-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chen Y, Feeley TH. Social support, social strain, loneliness, and well-being among older adults. J Soc Pers Relat 2014;31:141–61. 10.1177/0265407513488728 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shiovitz-Ezra S, Leitsch SA. The role of social relationships in predicting loneliness: The national social life, health, and aging project. Soc Work Res 2010;34:157–67. 10.1093/swr/34.3.157 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rogers A, Brooks H, Vassilev I, et al. . Why less may be more: a mixed methods study of the work and relatedness of ’weak ties' in supporting long-term condition self-management. Implement Sci 2014;9:19 10.1186/1748-5908-9-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gesell SB, Barkin SL, Valente TW. Social network diagnostics: a tool for monitoring group interventions. Implement Sci 2013;8:116 10.1186/1748-5908-8-116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Crookes DM, Shelton RC, Tehranifar P, et al. . Social networks and social support for healthy eating among Latina breast cancer survivors: implications for social and behavioral interventions. J Cancer Surviv 2016;10 10.1007/s11764-015-0475-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Uchino BN, Ruiz JM, Smith TW, et al. . The strength of family ties: Perceptions of network relationship quality and levels of c-reactive proteins in the north texas heart study. Ann Behav Med 2015;49:776–81. 10.1007/s12160-015-9699-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Druss BG, Zhao L, von Esenwein SA, et al. . The Health and Recovery Peer (HARP) Program: a peer-led intervention to improve medical self-management for persons with serious mental illness. Schizophr Res 2010;118(1-3):264–70. 10.1016/j.schres.2010.01.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Brito K, Edirimanne S, Eslick GD. The extent of improvement of health-related quality of life as assessed by the SF36 and Paseika scales after parathyroidectomy in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg 2015;13:245–9. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bekelman DB, Hooker S, Nowels CT, et al. . Feasibility and acceptability of a collaborative care intervention to improve symptoms and quality of life in chronic heart failure: mixed methods pilot trial. J Palliat Med 2014;17:145–51. 10.1089/jpm.2013.0143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chan R, Brooks R, Erlich J, et al. . How do clinical and psychological variables relate to quality of life in end-stage renal disease? Validating a proximal-distal model. Qual Life Res 2014;23:677–86. 10.1007/s11136-013-0499-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bakas T, McLennon SM, Carpenter JS, et al. . Systematic review of health-related quality of life models. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2012;10:134 10.1186/1477-7525-10-134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Phillips VL, Bonakdar Tehrani A, Langmuir H, et al. . Treating urge incontinence in older women: A cost-effective investment in Quality-Adjusted Life-Years (QALY). J Geriatr 2015;2015:1–7. 10.1155/2015/703425 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dumoulin C, Hay-Smith J, Habée-Séguin GM, et al. . Pelvic floor muscle training versus no treatment, or inactive control treatments, for urinary incontinence in women: a short version Cochrane systematic review with meta-analysis. Neurourol Urodyn 2015;34:300–8. 10.1002/nau.22700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fritel X, Varnoux N, Zins M, et al. . Symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse at midlife, quality of life, and risk factors. Obstet Gynecol 2009;113:609–16. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181985312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kirchengast S, Haslinger B. Gender differences in health-related quality of life among healthy aged and old-aged Austrians: cross-sectional analysis. Gend Med 2008;5:270–8. 10.1016/j.genm.2008.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mundet L, Ribas Y, Arco S, et al. . Quality of life differences in female and male patients with fecal incontinence. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2016;22:94–101. 10.5056/jnm15088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.