Abstract

Objectives

This study aims to review the evidence of sarcopenia as a predictor of all-cause mortality among nursing home residents.

Design

Systematic review and meta-analysis of observational cohort studies.

Data sources

PubMed, EMBASE and the Cochrane Library databases were searched for relevant articles.

Participants

Nursing home residents.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

All-cause mortality.

Data analysis

Summary-adjusted HRs or risk ratios (RRs) were calculated by fixed-effects model. The risk of bias was assessed by Newcastle-Ottawa Scale.

Results

Of 2292 studies identified through the systematic review, six studies (1494 participants) were included in the meta-analysis. Sarcopenia was significantly associated with a higher risk for all-cause mortality among nursing home residents (pooled HR 1.86, 95% CI 1.42 to 2.45, p<0.001, I2=0). In addition, the subgroup analysis demonstrated that sarcopenia was associated with all-cause mortality (pooled HR 1.87,95% CI 1.38 to 2.52, p<0.001) when studies with a follow-up period of 1 year or more were analysed; however, this was not found for studies with the follow-up period less than 1 year. Furthermore, sarcopenia was significantly associated with the risk of mortality among older nursing home residents when using bioelectrical impedance analysis to diagnosis muscle mass (pooled HR 1.88, 95% CI 1.39 to 2.53, p<0.001); whereas, it was not found when anthropometric measures were used to diagnosis muscle mass.

Conclusion

Sarcopenia is a significant predictor of all-cause mortality among older nursing home residents. Therefore, it is important to diagnose and treat sarcopenia to reduce mortality rates among nursing home residents.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42018081668

Keywords: sarcopenia, all-cause mortality, nursing home, meta-analysis, all-cause mortality

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To the best of our knowledge, it is the first meta-analysis to explore the relationship between sarcopenia and all-cause mortality among elderly nursing home residents.

An extensive search process in an electronic database was used and methodological quality was assessed; we also tested the heterogeneity and publication bias and performed sensitivity analysis among the included studies.

This systematic review and meta-analysis assessed the overall quality of the evidence by using Newcastle-Ottawa Scale approach for prospective observational studies and conducted a meta-analysis and subgroup analysis.

The number of studies included in this analysis was insufficient, and the size sample was relatively small.

Different cut-off values for the muscle mass might affect the relationship between sarcopenia and all-cause mortality.

Introduction

Sarcopenia is a common syndrome characterised by a loss of muscle mass and strength with functional impairment and adverse health outcomes due to cumulative deficits of multiple systems.1 Nursing home residents are at a particularly high risk for sarcopenia.2 According to studies, the prevalence of sarcopenia was 1%–29% for community-dwelling older adults, 14%–85.4% in nursing homes2–4 and 10%–24.3% for those in hospitals.5 Sarcopenia leads to a worse outcome in elderly people, including physical disability, falls, fractures, poor quality of life, mortality and hospitalisation.6–8 Among these, mortality might be considered the most important outcome in elderly people. So far, the relationship between mortality and operational criteria that define sarcopenia has been well described in community-dwelling older adults and hospitalised patients. A recent meta-analysis study, Liu et al, 9 analysed sarcopenia and mortality and concluded that sarcopenia is a predictor of all-cause mortality among community-dwelling older people. However, there is no consistent conclusion regarding the relationship between sarcopenia and mortality among nursing home residents. It has been shown that the mortality rate in nursing homes10 is approximately twofold higher than that in the community11–13; therefore, it is very important to confirm the risk factors for mortality among nursing home residents.

Several studies found that elderly people with sarcopenia were predictors of all-cause mortality among nursing home residents.14 15 However, some studies did not find any significant relationship between sarcopenia and all-cause mortality.16–19 Given the observed contradictory relationship between sarcopenia and all-cause mortality among nursing home residents in some studies, further studies are needed. However, no systematic reviews of meta-analysis studies on this topic have been conducted in the literature. Therefore, our study aims to identify and compare prospective cohort studies examining sarcopenia as a predictor of all-cause mortality among nursing home residents according to the Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines.

Materials and methods

This meta-analysis was conducted according to the MOOSE guidelines.20

Search strategy and selection criteria

A systematic literature search was conducted in MEDLINE (via PubMed 1946 to November 2017), EMBASE (via EMBASE November 2017) and Cochrane CENTRAL Library (via Cochrane Library November 2017). The search strategy was tailored according to each database. We used a combination of keywords such as mortality (mortality*), OR death (death*), OR survival (survival*) and sarcopenia (sarcopenia*), as well as MeSH terms. We also used subject terms and truncation symbols in our search strategy. We searched the potential grey studies through Google Scholar. Furthermore, we carried out a manual search on the references of included studies. The full search strategy for three databases has been provided as a supplementary file.

Study selection

These studies which were identified by our search strategy were reviewed by teams of two independently blinded investigators (XZ and CW) who evaluated each title and abstract. In case of disagreement (whether to include or exclude studies), the issue was discussed and a third reviewer evaluated the study until the reviewers reached consensus.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The following eligibility and exclusion criteria were prespecified. Studies had to fulfil the following four inclusion criteria: (1) prospective cohort studies, (2) studies investigating whether sarcopenia was a predictor of mortality, (3) studies reporting clear diagnostic criteria for sarcopenia, (4) type of participant: elderly adult in nursing home or nursing care. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) type of participant: community-dwelling older people (aged 65 years or older) or hospitalised older people; (2) article type: only abstract, letters and laboratory research; review articles; (3) insufficient data; (4) other languages of studies, except English; (5) no clear definition of sarcopenia.

Data extraction

Two investigators (XZ, CW) independently abstracted the data from the selected studies using a standardised data abstraction form. The following information was extracted from included papers: author, country, year of publication, demographic characteristics of participants (eg, sample size, male proportion), measurement methods of sarcopenia, follow-up period, adjusted variable and study quality. The reviewers cross-checked all extracted data. Disagreements were resolved by discussion until consensus was reached.

Assessment of risk bias

Assessment of risk of bias was performed by two independent reviewers (XZ, CW) according to the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS)21: (1) representativeness of the exposed cohort, (2) comparability of group, (3) blinding of investigators who measured outcomes, (4) the time and completeness of follow-up, (5) contamination bias and (6) other potential sources of bias. The total score of the scale is 9 points. When the total score is ≥5 points, it is considered as a high-quality research.

Statistical analysis

The STATA V.14.0 was independently used for all analyses by two authors (XZ, QD). HRs, OR and their 95% CIs of mortality for sarcopenia compared with non-sarcopenia were extracted from studies for future meta-analysis. Risk ratio (RR) was considered equivalent to HR in our prospective cohort studies, which was reported in Willi’s22 study and Mahmoud’s study.23 If a study reported the effect size as an OR, it was converted to RR using a previously described formula.24 All the effect of HR or RR was converted to ln(HR) or ln(RR) for ratio in meta-analysis, subgroup analyses were conducted by different diagnosis tools for muscle mass and follow-up period if there was more than one study in the subgroup. The statistical heterogeneity among the included studies was examined with Cochran’s Q statistic using χ2 and I2 statistics, and I2 value of 25%, 50% and 75% represented the cut-off of low, moderate and high heterogeneity, respectively. If heterogeneity was found to be reasonably high between studies, the random-effects model was used. Otherwise, the fixed-effects model was used. Results were illustrated using forest plots, and Begg’s test was done to plot the log HR against its SE for assessment of potential publication bias.

Patient and public involvement

The patients or public were not involved in the study.

Results

Search results

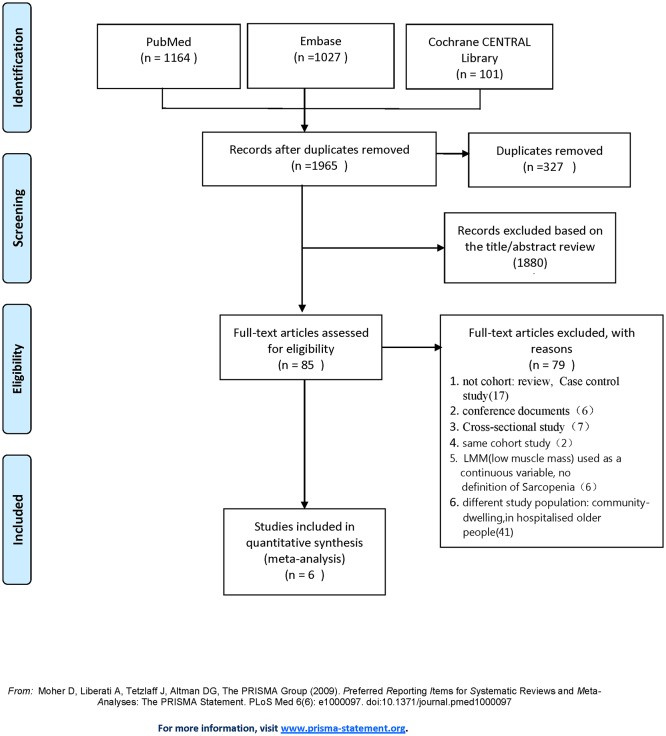

The literature search strategy initially identified 2292 articles. After removal of duplicates, 1965 articles were screened for potential eligibility. A total of 85 publications remained for further consideration. Then we screened titles and abstracts and removed unrelated articles. Of these articles, 30 were removed because of non-cohort studies (eg, review articles, conference documents, cross-sectional study, case–control study), and six were removed because they had no clear definition of sarcopenia; moreover, 41 were removed on account of different study population: community-dwelling older people, patients in hospital and used the same cohorts (n=2). These studies were screened according to the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria for inclusion in the meta-analysis, resulting in a total of six eligible studies (figure 1).

Figure 1.

The flow diagram of studies selection. LMM, low muscle mass.

Included studies

Six prospective cohort studies were included in our meta-analysis with 1494 total participants. Study characteristics of included papers are displayed in table 1. Two studies were conducted in Turkey,17 18 one study in Italy,15 one study in Australia,16 one study in Belgium14 and one study in Israel19. All the studies selected all-cause mortality as the clinical outcome and five studies used the sarcopenia criteria of European Working Group for Sarcopenia (EWGSOP), the other19 used National Institute of Healt (NIH)-sponsored workshop25 to diagnose sarcopenia. The EWGSOP1 recommends using the presence of both low muscle function (strength or performance) and low muscle mass for the diagnosis of sarcopenia. Thus, diagnosis of sarcopenia in the present study required the documentation of low muscle mass plus the documentation of either low muscle strength or low physical performance. The prevalence of sarcopenia ranged from 32.8% to 73.3%. The largest study consisted of 662 men and women, and the smallest cohort had only 58 individuals. Follow-up periods were no longer varying from 6 months to 24 months, and the adjusted HR was displayed in four studies, and one used OR and the other used RR. Table 2 shows the different tools and cut-off of muscle mass, muscle strength and physical performance. Four studies used bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) as a diagnostic criterion for muscle mass, and the other two studies used anthropometric measures as diagnostic criteria.

Table 1.

Summary of included studies on sarcopenia associated with all-cause mortality

| Author | Country | Year | Male, % | Sample no | Age of patients, years | Prevalence, % | Follow-up period | mortality rate, % | Effect measure |

Adjusted or crude HR/OR |

Quality* |

| Saka et al 17 |

Turkey | 2016 | 51 | 402 | 78.0±7.9 | 73.3 | 12 months | 16.2 | HR | Adjusted | 8 |

| Yalcin et al 18 |

Turkey | 2017 | 54.3 | 141 | 79.17±7.99 | 53.9 | 24 months | 23.4 | HR | Age, sex, BMI, Calf circumference, MMSE, MNA, cerebrovascular diseases, osteoarthritis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, activity of daily living impairment, diabetes, dementia. |

7 |

| Landi et al 15 |

Italy | 2012 | 25 | 122 | 84.1±4.8 | 32.8 | 6 months | 21.3 | HRs | Age, sex, cerebrovascular diseases, osteoarthritis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, activity of daily living impairment |

8 |

| Henwood et al 16 |

Australia | 2017 | 29.3 | 58 | 85.7±8.2 | 51.7 | 18 months | 21.6 | RR | Age, sex, BMI, MNA, physical activity | 6 |

| Buckinx et al 14 |

Belgium | 2018 | 27.5 | 662 | 83.2±8.99 | 36.2 | 12 months | 15.9 | OR | Age, sex, BMI, frailty, waist circumference, calf circumference, arm circumference, wrist circumference, walking support, drugs consumed, medical history, MMSE, Minnesota, MNA, body fat, SF-36, EuroQol five dimensions, EuroQol-Visual Analogue Scale, Katz score, fear of falling, Tinetti test, TUG test, SPPB test, gait speed, grip strength, peak expiratory flow, isometric strength |

7 |

| Kimyagarov et al 19 |

Israel | 2012 | 41.2 | 109 | 84.9±7.4 | 40.3 | 12 months | 61.5 | HR | Age, sex, BMI Charlson Comorbidity Index |

7 |

European Working Group for Sarcopenia in Older Persons defines sarcopenia in men as ALM adjusted for height squared <7.25 kg/m2 combined with low hand grip strength (<30 kg) and/or low gait speed (<0.8 m/s).

*Quality of the studies was assessed with Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS).

BMI, body mass index; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; MNA, Mini-Nutritional Assessment; RR, risk ratio; SF-36, 36-item Short Form Health Survey Questionnaires; SPPB test, short physical performance battery; TUG test, timed up and go.

Table 2.

Study and Sarcopenia criteria

| Study | Sarcopenia criteria | Item, tool, cut-off points | Ref | |||||

| Muscle mass | Muscle strength | Physical performance | ||||||

| Tool | Cut-off points | Tool | Cut-off points | Tool | Cut-off point | |||

| Yalcin et al | EWFSOP | BIA | Men: SMI ≤8.87 kg/m2

Women: SMI ≤6.42 kg/m2 |

Hand grip strength | Men: HGS<30 kg Women: HGS<20 kg |

Gait speed: 4 m | ≤0.8 m/s | 18 |

| Buckinx et al | EWFSOP | BIA | Men: SMI ≤8.87 kg/m2

Women: SMI ≤6.42 kg/m2 |

Hand grip strength | None | SPPB: short physical performance battery |

≤0.8 m/s | 14 |

| Henwood et al | EWFSOP | BIA | Men: SMI <8.87 kg/m2

Women: SMI <6.42 kg/m2 |

Hand grip strength |

Men: HGS<30 kg Women: HGS<20 kg |

SPPB | ≤0.8 m/s | 16 |

| Saka et al | EWFSOP | anthropometric measures | CC <31 cm in men and women MUAMC <23.8 cm in men MUAMC <23.3 cm in women |

Hand grip strength |

Men: HGS<30 kg Women: HGS<20 kg |

Gait speed: 4 m | ≤0.8 m/s | 17 |

| Kimyagarov et al | NIH-sponsored workshop | anthropometric measures | SMM index: (males) <10.5 kg/m2 (females) <8.5 kg/m2 | Manual muscle testing (MMT) | MMT*score <106 | None | None | 19 |

| Landi et al | EWFSOP | BIA | Men: SMI <8.87 kg/m2

Women: SMI <6.42 kg/m2 |

Hand grip strength |

Men: HGS<30 kg Women: HGS<20 kg |

Gait speed: 4 m | ≤0.8 m/s | 15 |

*MMT: an isometric semiquantitative measurement of eight limb muscles groups, in which muscle strength has subjective grades.

On the classic 0–5 point scale, the lowest grade (0) indicates no contractility or muscle activation, and the highest possible grade (160 points) represents full resistance.

BIA, bioelectrical impedance analysis; CC, calf circumference; EWFSOP, European Working Group for Sarcopenia; HGS, handgrip strength; MUAMC: mid upper arm muscle circumference SMI: Skeletal Muscle Index obtained by absolute skeletal muscle mass divided by height by meters squared (kg/m2).

Quality assessment

The methodological quality evaluation using NOS of all items is shown in table 3. The score of each study ranged from 6 to 8. The scores of five studies were more than 7.

Table 3.

Result of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale quality assessment

| Newcastle-Ottawa Scale | Saka et al | Yalcin et al | Landi et al |

Kimyagarov et al | Henwood et al | Buckinx et al | |

| Selection (4) | Representativeness of the exposed cohort | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Selection of the non-exposed cohort | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Ascertainment of exposure | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at start of study | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Comparability (2) | Comparability of cohorts on the basis of the design or analysis | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Outcome (3) | Assessment of outcome | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Was follow-up long enough for outcome to occur | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Adequacy of follow-up of cohorts | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Quality (9) | Total | 8 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 7 |

Sarcopenia as a predictor of mortality

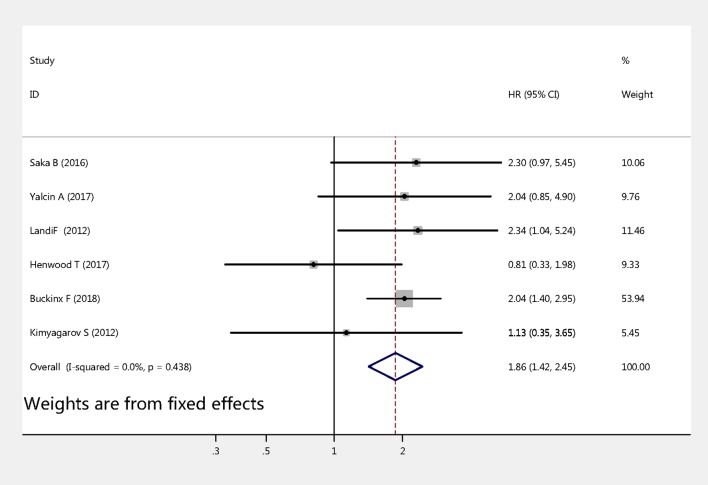

Meta-analysis of studies

Six studies examined the association between sarcopenia and mortality among nursing home residents. The pooled HRs values were calculated by fixed-effects models. As shown in figure 2, the HR of all-cause mortality for sarcopenia versus non-sarcopenia was 1.86 (95% CI 1.42 to 2.45, p<0.001). No significant heterogeneity was observed across these studies (Q-value=4.82, df=5, I2=0%, p=0.438).

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis of the association between sarcopenia and mortality among older nursing home residents.

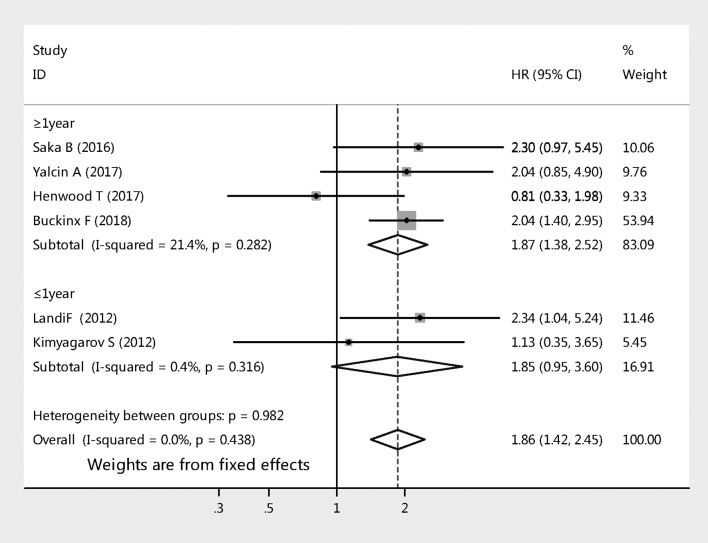

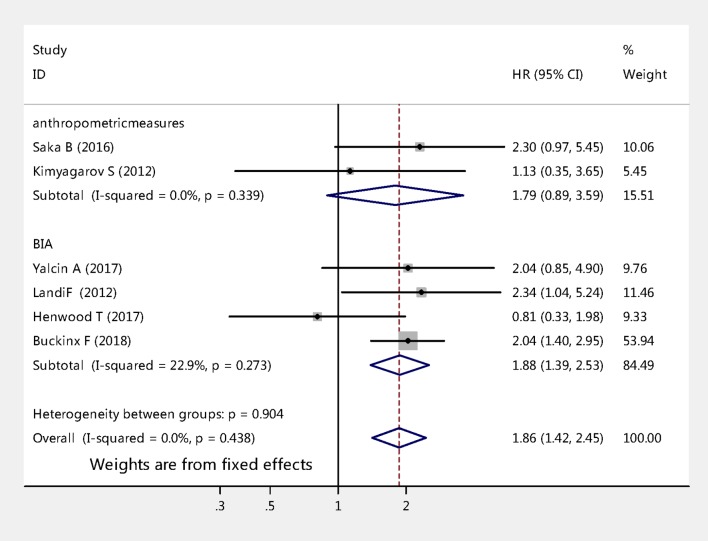

Subgroup analysis

The six studies with HR of all-cause mortality risks for sarcopenia among nursing home residents were further analysed by subgroup. Figure 3 compares all-cause mortality risk stratified by length of follow-up for sarcopenia. Two studies that followed up 231 cases for a period of less than 1 year (pooled HR 1.85, 95% CI 0.95 to 3.60, p=0.070); whereas the analysis of other four studies that followed up 1263 cases for a period of 1 year or more (pooled HR 1.87, 95% CI 1.38 to 2.52, p<0.001). Figure 4 shows sarcopenia was significantly associated with the risk of mortality among nursing home residents when using BIA to diagnose muscle mass (pooled effect size=1.88, 95% CI 1.39 to 2.53, p<0.001), whereas it was not associated when using anthropometric measures to diagnosis muscle mass (pooled effect size=1.79, 95% CI 0.89 to 3.59, p=0.100).

Figure 3.

Subgroup analyses of the meta-analysis according to length of follow-up.

Figure 4.

Subgroup analyses of the meta-analysis according to different diagnosis tools for muscle mass.

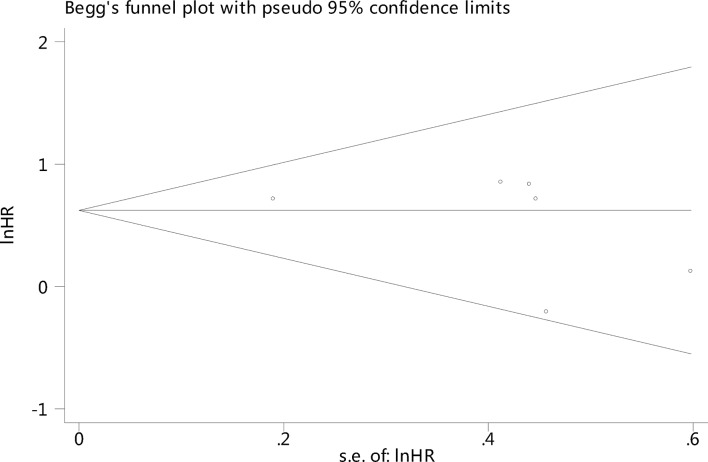

Publication bias assessment

There was no significant publication bias among the studies using Begg’s test: p=0.386 (figure 5).

Figure 5.

Funnel plot of sarcopenia and all-cause mortality among older nursing home residents.

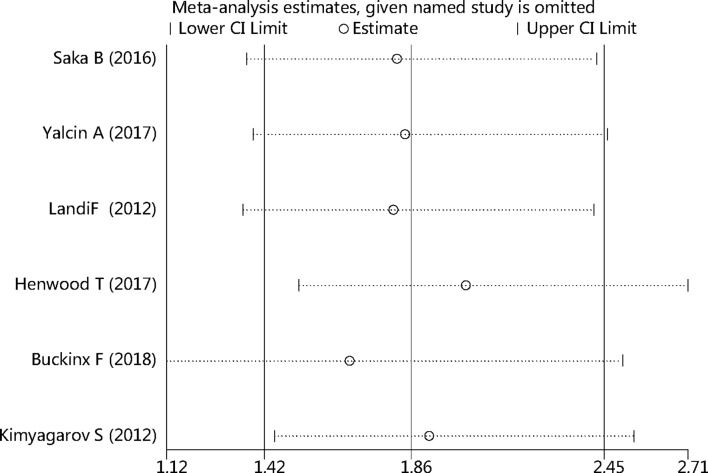

Sensitivity analysis of all studies

We conducted a sensitivity analysis of sarcopenia and mortality by omitting one of the included studies each time, and pooling the others together to find which study would influence the main pooled HR. No statistically significant changes were found, as shown in figure 6.

Figure 6.

Sensitivity analysis of all studies.

Discussion

In this meta-analysis, we found evidence suggesting the risk of all-cause mortality among nursing home residents with sarcopenia was higher than that among nursing home residents without sarcopenia. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis to explore the relationship between sarcopenia and all-cause mortality among nursing home residents. Our study indicated assessing sarcopenia is really important among the elderly that live in nursing homes.

Liu et al 9 implemented a systematic review and meta-analysis regarding the association of sarcopenia with mortality in 2016, published in 2017. However, this review included a population entirely of community-dwelling older people. So far, Chang and Lin26 and Beaudart et al 27 both performed a systematic review to evaluate the link between sarcopenia and all-cause mortality; however, there were some methodological shortcomings, such as various diagnostic criteria of sarcopenia, crude ORs as effect, various population involving community-dwelling older people and hospitalised patients. Although a subgroup of nursing home residents was analysed in Beaudart’s study, there are only two studies that were assessed, which may be underestimated or overestimated their result. Our review included six studies which focus only on the association of mortality and sarcopenia in nursing home residents. The results were stable and reliable after we tested the heterogeneity and publication bias and performed sensitivity analysis among the included studies.

This meta-analysis of six cohort studies shows sarcopenia is an important predictor of all-cause mortality among nursing home residents. The pooled HR value of all-cause mortality was 1.86 (95% CI 1.41 to 2.45, p<0.001, I2=0%). The small I2 suggesting no significant heterogeneity was shown across these studies. In addition, our study’s pooled HR value is higher than that of Liu et al 9 (1.60, 95% CI 1.24 to 2.06); the primary reason was the different type of population. Those living in a nursing home usually had worse heath conditions and more comorbidities, more disability and more geriatric syndromes, such as cognitive dysfunction and malnutrition.17 28–30 This comprehensive risk factor may aggravate the process of sarcopenia.

In our present study, the prevalence of sarcopenia varied from 32.8% to 73.3%. The difference was mainly due to the mean age, various population and different diagnostic tools, particularly the ways that researchers measured muscle mass. A previous study showed that sarcopenia was associated with mortality when BIA was used to diagnose muscle mass.31 In this present study, we confirmed that sarcopenia was associated with all-cause mortality using BIA to diagnose muscle mass; however, the association was not found when using anthropometric measures. According to the EWGSOP,1 BIA is the most common tool for diagnosing muscle mass; moreover, the test is inexpensive, easy to use, readily reproducible and appropriate for both ambulatory and bedridden patients, which may be considered a portable alternative to dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry in nursing homes. However, the method of anthropometric measures was based on mid-upper-arm circumference and skin fold thickness26 32; therefore, age-related changes in fat deposits and loss of skin elasticity contribute to errors of estimation in older nursing home residents, which are prone to produce errors.33 Furthermore, anthropometric measures were not recommended for routine use in the diagnosis of sarcopenia.

It has been demonstrated that length follow-up could influence the association between sarcopenia and mortality.9 Our study showed that the subgroup of length of follow-up analysis demonstrated that follow-up period of 1 year or more was associated with all-cause mortality (pooled HR 1.87, 95% CI 1.38 to 2.52, p<0.001); however, it was not found with the follow-up period of less than 1 year (pooled HR 1.85, 95% CI 0.95 to 3.60, p=0.070). It is noticed that there were only 231 cases in the two studies with the follow-up period of less than 1 year and it is likely that the numbers of studies and included cases for short-term analysis were too small to have a significant result. Therefore, more perspective cohort studies about this issue must be conducted in the future.

The underlying mechanisms between sarcopenia and a higher risk of all-cause mortality were unable to draw a conclusion; some aspects should be mentioned at least. First, the association between sarcopenia and mortality may be explained by the hypothesised adverse effects of a low muscle mass in older people. Several studies showed that low muscle mass is highly associated with increased mortality.34–36 In addition, elderly people in nursing homes are at high risk of malnutrition,37 which aggravates low muscle mass, resulting in an increased mortality rate. Second, sarcopenia is linked to multiple factors ranging from ageing process,38 multiple chronic health conditions, unhealthy lifestyle, 39 hormonal factors, 40 inflammation41 and so on.42 Meanwhile, the above factors are considered to be linked with mortality and the development of multifactor worsened the situation of sarcopenia, leading to a passive adaptation to adversity or external stressors which in turn generate increased poor adverse outcomes.43 Third, according to the study of Fried et al,44 sarcopenia played a critical aetiologic role in the frailty process, which is related, through frailty, to pernicious consequences, for instance, recurrent falls, bone fracture, disability, multiple emergency room visits and hospital admissions and eventually death.45 46 Moreover, sarcopenia is considered to increase the risk of falls among the elderly,47 and falls were the major causes of death in nursing home residents.48 Sarcopenia is a geriatric syndrome rather than a disease; the mechanism of sarcopenia is very complex, which needs more research to explore.

Our meta-analysis review has multiple strengths and some limitations. One strength was that we used an extensive search process in electronic databases and assessed methodological quality and tested the heterogeneity and publication bias among the included studies. Another strength was that the included original studies were all of prospective design, which minimised the possibility of recall bias and selection bias. However, our study also has some limitations. First, two included studies did not directly report the HR in the sarcopenia group versus the non-sarcopenia group, but used an approximation of OR to RR, and from RR to HR in the sarcopenia group, which might not show an accurate HR value. Therefore, this approach may lead to method heterogeneity. Another concern was that the cut-off for the muscle mass was different in some studies, which caused the prevalence of sarcopenia to be various, thus potentially influenced the result. Third, the number of included studies in this analysis was insufficient, and the sample size was relatively small. Fourth, we ignored the different adjusted confounding factors of the derived HR from different studies. Fifth, the language of studies was limited to English, and consequently some data from important studies published in other languages have been ignored, which may result in potential language bias. In addition, the follow-up was relatively short for the necessary latency, which may underestimate the results.

Conclusion

This study provides evidence that sarcopenia is a significant predictor of all-cause mortality among nursing home residents based on the comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Further studies need to be provided with evidence for specific interventions to prevent and treat sarcopenia, which can reduce mortality in people living in a nursing home Supplementary file 1.

bmjopen-2017-021252supp001.pdf (159.2KB, pdf)

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staffs of the Department of Emergency Medicine, people’s hospital of Baoan, Shenzhen for their guidance and support.

Footnotes

XZ and CW contributed equally.

Contributors: XZ was responsible for producing the initial draft of the manuscript. CW was responsible for data extraction and for producing the initial draft of the manuscript. QD was responsible for data extraction. WZ was responsible for screening the papers and quality assessment. XX was responsible for screening the papers. YY was responsible for quality assessment, statistical analysis and revision of the manuscript. All the authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All the data can obtain in the electronic databases (PubMed, EMBASE and the Cochrane Library).

References

- 1. Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Baeyens JP, Bauer JM, et al. . Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: report of the European Working Group on sarcopenia in older people. Age Ageing 2010;39:412–23. 10.1093/ageing/afq034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Landi F, Liperoti R, Fusco D, et al. . Prevalence and risk factors of sarcopenia among nursing home older residents. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2012;67:48–55. 10.1093/gerona/glr035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Senior HE, Henwood TR, Beller EM, et al. . Prevalence and risk factors of sarcopenia among adults living in nursing homes. Maturitas 2015;82:418–23. 10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bahat G, Saka B, Tufan F, et al. . Prevalence of sarcopenia and its association with functional and nutritional status among male residents in a nursing home in Turkey. Aging Male 2010;13:211–4. 10.3109/13685538.2010.489130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Landi F, Schneider SM, et al. . Prevalence of and interventions for sarcopenia in ageing adults: a systematic review. Report of the International Sarcopenia Initiative (EWGSOP and IWGS). Age Ageing 2014;43:748–59. 10.1093/ageing/afu115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Beaudart C, McCloskey E, Bruyère O, et al. . Sarcopenia in daily practice: assessment and management. BMC Geriatr 2016;16:170 10.1186/s12877-016-0349-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Woo J. Sarcopenia. Clin Geriatr Med 2017;33:305–14. 10.1016/j.cger.2017.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Landi F, Liperoti R, Russo A, et al. . Sarcopenia as a risk factor for falls in elderly individuals: results from the ilSIRENTE study. Clin Nutr 2012;31:652–8. 10.1016/j.clnu.2012.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Liu P, Hao Q, Hai S, et al. . Sarcopenia as a predictor of all-cause mortality among community-dwelling older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Maturitas 2017;103:16–22. 10.1016/j.maturitas.2017.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Goldberg TH, Botero A. Causes of death in elderly nursing home residents. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2008;9:565–7. 10.1016/j.jamda.2008.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kim JH, Lim S, Choi SH, et al. . Sarcopenia: an independent predictor of mortality in community-dwelling older Korean men. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2014;69:1244–52. 10.1093/gerona/glu050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wauters M, Elseviers M, Vaes B, et al. . Mortality, hospitalisation, institutionalisation in community-dwelling oldest old: the impact of medication. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2016;65:9–16. 10.1016/j.archger.2016.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Arango-Lopera VE, Arroyo P, Gutiérrez-Robledo LM, et al. . Mortality as an adverse outcome of sarcopenia. J Nutr Health Aging 2013;17:259–62. 10.1007/s12603-012-0434-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Buckinx F, Croisier JL, Reginster JY, et al. . Prediction of the incidence of falls and deaths among elderly nursing home residents: the SENIOR study. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2018;19:18–24. 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Landi F, Liperoti R, Fusco D, et al. . Sarcopenia and mortality among older nursing home residents. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2012;13:121–6. 10.1016/j.jamda.2011.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Henwood T, Hassan B, Swinton P, et al. . Consequences of sarcopenia among nursing home residents at long-term follow-up. Geriatr Nurs 2017;38:406–11. 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2017.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Saka B, Ozkaya H, Karisik E, et al. . Malnutrition and sarcopenia are associated with increased mortality rate in nursing home residents: A prospective study. Eur Geriatr Med 2016;7:232–8. 10.1016/j.eurger.2015.12.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yalcin A, Aras S, Atmis V, et al. . Sarcopenia and mortality in older people living in a nursing home in Turkey. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2017;17:1118–24. 10.1111/ggi.12840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kimyagarov S, Klid R, Fleissig Y, et al. . Skeletal muscle mass abnormalities are associated with survival rates of institutionalized elderly nursing home residents. J Nutr Health Aging 2012;16:432–6. 10.1007/s12603-012-0005-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. . Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 2000;283:2008–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol 2010;25:603–5. 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Willi C, Bodenmann P, Ghali WA, et al. . Active smoking and the risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2007;298:2654–64. 10.1001/jama.298.22.2654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mahmoud AN, Mentias A, Elgendy AY, et al. . Migraine and the risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events: a meta-analysis of 16 cohort studies including 1 152 407 subjects. BMJ Open 2018;8:e020498 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Grant RL. Converting an odds ratio to a range of plausible relative risks for better communication of research findings. BMJ 2014;348:f7450 10.1136/bmj.f7450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Roubenoff R. The pathophysiology of wasting in the elderly. J Nutr 1999;129:256S–9. 10.1093/jn/129.1.256S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chang SF, Lin PL. Systematic literature review and meta-analysis of the association of sarcopenia with mortality. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2016;13:153–62. 10.1111/wvn.12147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Beaudart C, Zaaria M, Pasleau F, et al. . Health outcomes of sarcopenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2017;12:e0169548 10.1371/journal.pone.0169548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hoffmann F, Kaduszkiewicz H, Glaeske G, et al. . Prevalence of dementia in nursing home and community-dwelling older adults in Germany. Aging Clin Exp Res 2014;26:555–9. 10.1007/s40520-014-0210-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ronald LA, McGregor MJ, McGrail KM, et al. . Hospitalization rates of nursing home residents and community-dwelling seniors in British Columbia. Can J Aging 2008;27:109–15. 10.3138/cja.27.1.109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Benzinger P, Becker C, Kerse N, et al. . Pelvic fracture rates in community-living people with and without disability and in residents of nursing homes. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2013;14:673–8. 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Brown JC, Harhay MO, Harhay MN. Sarcopenia and mortality among a population-based sample of community-dwelling older adults. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2016;7:290–8. 10.1002/jcsm.12073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rolland Y, Lauwers-Cances V, Cournot M, et al. . Sarcopenia, calf circumference, and physical function of elderly women: a cross-sectional study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51:1120–4. 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51362.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rolland Y, Czerwinski S, Abellan Van Kan G, et al. . Sarcopenia: its assessment, etiology, pathogenesis, consequences and future perspectives. J Nutr Health Aging 2008;12:433–50. 10.1007/BF02982704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Brown JC, Harhay MO, Harhay MN. Appendicular lean mass and mortality among prefrail and frail older adults. J Nutr Health Aging 2017;21:342–5. 10.1007/s12603-016-0753-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cesari M, Pahor M, Lauretani F, et al. . Skeletal muscle and mortality results from the InCHIANTI Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2009;64:377–84. 10.1093/gerona/gln031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wijnhoven HA, van Bokhorst-de van der Schueren MA, Heymans MW, et al. . Low mid-upper arm circumference, calf circumference, and body mass index and mortality in older persons. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2010;65:1107–14. 10.1093/gerona/glq100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Vandewoude MF, Alish CJ, Sauer AC, et al. . Malnutrition-sarcopenia syndrome: is this the future of nutrition screening and assessment for older adults? J Aging Res 2012;2012:1–8. 10.1155/2012/651570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Marzetti E, Lees HA, Wohlgemuth SE, et al. . Sarcopenia of aging: underlying cellular mechanisms and protection by calorie restriction. Biofactors 2009;35:28–35. 10.1002/biof.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Kiesswetter E, Drey M, et al. . Nutrition, frailty, and sarcopenia. Aging Clin Exp Res 2017;29:43–8. 10.1007/s40520-016-0709-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Martone AM, Lattanzio F, Abbatecola AM, et al. . Treating sarcopenia in older and oldest old. Curr Pharm Des 2015;21:1715–22. 10.2174/1381612821666150130122032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Westbury LD, Fuggle NR, Syddall HE, et al. . Relationships between markers of inflammation and muscle mass, strength and function: findings from the hertfordshire cohort study. Calcif Tissue Int 2018;102:287–95. 10.1007/s00223-017-0354-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Malafarina V, Uriz-Otano F, Iniesta R, et al. . Sarcopenia in the elderly: diagnosis, physiopathology and treatment. Maturitas 2012;71:109–14. 10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Landi F, Topinková E, et al. . Understanding sarcopenia as a geriatric syndrome. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2010;13:1–7. 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328333c1c1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. . Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001;56:M146–M157. 10.1093/gerona/56.3.M146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wick JY. Understanding frailty in the geriatric population. Consult Pharm 2011;26:634–45. 10.4140/TCP.n.2011.634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bernabei R, Martone AM, Vetrano DL, et al. . Frailty, physical frailty, sarcopenia: a new conceptual model. Stud Health Technol Inform 2014;203:78–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Matsumoto H, Tanimura C, Tanishima S, et al. . Sarcopenia is a risk factor for falling in independently living Japanese older adults: A 2-year prospective cohort study of the GAINA study. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2017;17:2124–30. 10.1111/ggi.13047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ibrahim JE, Bugeja L, Willoughby M, et al. . Premature deaths of nursing home residents: an epidemiological analysis. Med J Aust 2017;206:442–7. 10.5694/mja16.00873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-021252supp001.pdf (159.2KB, pdf)