Abstract

Background/Aims:

Many patients currently seek the Internet for health-related information without discerning the quality or bias of the evidence presented. Biologic agents have become the mainstay of therapy in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and it is important that patients have access to high-quality information when exploring the various available agents to make informed decisions about their therapy. The primary aim of this study was to evaluate the quality of patient-searched Internet websites that describe the biologic agents used as treatment options for IBD. The secondary aim was to compare the quality of patient-searched with physician-recommended websites and to evaluate any differences.

Materials and Methods:

The DISCERN model was used to evaluate the quality of the information content of a total of 110 websites of all the biologic agents used in the treatment of IBD from July to September 2017. The first 10 “Google search” hits meeting the inclusion criteria for each agent were included. There were four additional physician-recommended websites that were evaluated for the purpose of the secondary aim of this study.

Results:

The mean DISCERN score among all websites combined was 3.21 out of a 5-point scale. The highest scoring website was “ema.europa.eu” at 4.13 whereas the lowest scoring website was “https://www.fda.gov” at 1.97 for Entyvio. There was no significant difference between patient-searched and physician-recommended websites, with a mean total score of 3.21 versus 3.63, respectively (P value of 0.158).

Conclusions:

The combined quality of Internet web-based resources used for each drug was fairly consistent in scoring (intermediate to slightly above average). There was no significant advantage in the overall combined scores of the pooled physician-recommended websites when compared with the patient-searched websites.

Keywords: Biologic agents, inflammatory bowel disease, internet, patient education, website

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) consists of ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn's disease (CD) and can present with various symptomatology and degrees of severity. Epidemiology data suggest approximate incidence rates of up to 20 cases per 100,000 person-years in North America alone and a prevalence rate exceeding 200 per 100,000 population in the United States for each entity.[1,2,3] Traditional therapies have included sulfasalazine, 5-aminosalicylates, corticosteroids, and immunosuppressive agents. The development of biologic agents with various mechanisms of action adds to the complexity of treatment of IBD and has revolutionized the management paradigms. In years past, health care professionals were often the primary source of information for patients with regards to diseases and therapies, and may have provided written materials such as handouts or brochures. In the modern era, patients now turn to the most convenient and largest source of information worldwide, the Internet.

The Internet has certainly revolutionized the ease of access to information. “Google” is among the most common search engines used today. Recent estimates approximate that 10 million people had access to the Internet in the mid-1990s and this number exceeds 2 billion people worldwide today.[4] In 2010, 80% of Canadian households had access to the Internet, and this number is much higher today.[5] More specifically, a recent IBD clinic study published in 2014 estimated that approximately 93% of patients use the Internet to acquire health-related information and 33% of patients understand the influence that their searches have on their choice of medication.[6] What is more striking is that 71% of patients indicated confidence in their ability to obtain factual contents on the Internet without having the necessary tools to determine the quality of information on these websites.[6] Similar prior studies found as many as >90% of patients presenting to various outpatient gastroenterology clinics reporting Internet usage for obtaining health-related information, but only a small proportion did so based on advice from their physician.[7,8,9,10,11,12,13] Therefore, searching the Internet without guidance to the websites with high-quality content may leave patients vulnerable to misleading and deceptive information and jeopardize their informed decision-making process.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the quality of the content posted on the websites that are potentially and commonly visited by IBD patients pertaining to the information regarding variously prescribed biologic agents.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We used the validated DISCERN scoring instrument for the purpose of evaluating these websites.[14,15,16,17,18] The DISCERN instrument evaluates 16 items, each on a 1- to 5-point scale (with 1 = “not at all” and 5 = “completely true”).[17] The items are divided into three sections, with the first eight items evaluating the content reliability and the remaining seven items evaluating the treatment information quality, with the last (16th) item giving an overall quality score on the same scale.[17] Therefore, higher scores indicate better content quality of the website. The DISCERN guide should only be used once familiarized with the full DISCERN instrument, but essentially will describe a good quality publication or website related to treatment choices, as one that will:

-

Assess content reliability:

- Have explicit aims

- Achieve its aims

- Be relevant to the consumers

- Make sources of information explicit

- Make date of information explicit

- Be balanced and unbiased

- List the additional sources of information

- Refer to the areas of uncertainty

-

Assess treatment choices information quality:

-

9.Describe how the treatment works

-

10.Describe the benefits of the treatment

-

11.Describe the risks of the treatment

-

12.Describe what would happen without the treatment

-

13.Describe the effects of the treatment choices on overall quality of life

-

14.Make it clear that there may be more than one possible treatment choice

-

15.Provide support for shared decision making

-

9.

-

Assess overall rating of the publication:

-

16.Overall quality.

-

16.

A total of 11 biologic agent “terms” were included in this study, and for each term used, the first 10 different websites populated into the search engine “Google” were included for the evaluation. This ensures that the highest ranked websites populated in the first 1 to 2 pages and likely most accessible to patients are included. Duplicate website hits were excluded to avoid repetitive evaluation of the same website. All terms were searched on July 25, 2017, and documented into a spreadsheet for future evaluation using the DISCERN model, from July through September 2017. Searched biologic agent terms that were used included the following: “Remicade” (Janssen Canada, Toronto, Ontario), “Inflectra” (Pfizer Canada, Kirkland, Quebec), “Infliximab,” “Humira” (AbbVie Inc., Saint-Laurent, Quebec), “Adalimumab,” “Simponi” (Janssen Canada, Toronto, Ontario), “Golimumab,” “Entyvio” (Takeda Canada, Oakville, Ontario), “Vedolizumab,” “Stelara” (Janssen Canada, Toronto, Ontario), and “Ustekinumab.” These terms included all the Canadian-approved biologic products for IBD including various brands and their generic names of each agent available. We included brand and generic names of the different agents separately because each searched term generated a slightly different list of websites that patients might have visited to obtain drug information.

Inclusion criteria for the website eligibility required each website to include information pertaining to IBD. This was important given that some websites of the biologic agent searched may have focused exclusively on other disease entities they treated such as ankylosing spondylitis or rheumatoid arthritis. Another inclusion criteria was that each website must be written in English or has a “translation to English” tab option on the website's main page visited. Websites were excluded if they were video results (as most were very short commercials and we have not come across any evidence suggesting that the DISCERN model was ever validated to use in evaluating videos as it has been for written information or websites that the patients can navigate through), were duplicated sites, were in other languages without the on-site option to translate to English, or solely included information content limited to other disease entities other than IBD, which would make the contained information irrelevant to IBD patients. The first 10 websites meeting the inclusion criteria were selected to capture the commonly accessed websites that the patients might come across during their Internet search. The quality of the information presented on the website was not assessed at that point until a collection of all the websites were documented into a spreadsheet first.

The quality of the content for each website identified was assessed by two independent assessors using the validated DISCERN scoring model.[14,15,16,17,18] The website used for the DISCERN instrument is “www.discern.org.uk” consisting of 15 questions, as mentioned above, with an overall score given for Component 16 of the scoring model. Each assessor independently scored each question based on a scale of 1 to 5, with a score of 1 indicating an assessment of poor quality and 5 indicating highest quality. The two assessors were the two authors of this article. A trial of 10 websites evaluated independently by each assessor were compared before completing this study to ensure that a comparable approach and similar scoring method of the content of each website was followed. An allowance of 1-point score variation for each question between assessors, including the overall score assessment (Component 16), was allowed for the evaluation of each website. For each greater variation among the scores reviewed, a secondary review and consensus discussion of the DISCERN criterion was conducted between assessors to determine where the overlooked gap may have been before the re-scoring attempt. This was done three times overall throughout the 2 months of this study.

The DISCERN instrument was also used to evaluate four additional reputable websites of IBD-related National Societies and Foundations that physicians typically reference. These included “Crohn's and Colitis Foundation,” “Crohn's and Colitis Canada,” “Gastrointestinal Society,” and “Canadian Digestive Health Foundation.” These websites were evaluated and scored by the same two assessors, and similarly, there was no more than 1-point score variation for each question between both assessors.

Statistical analysis

Graphpad software was used for statistical analysis of the data, using an unpaired t test to calculate the two-tailed P values and confidence interval (CIs) between the patient-searched and the physician-recommended websites.

RESULTS

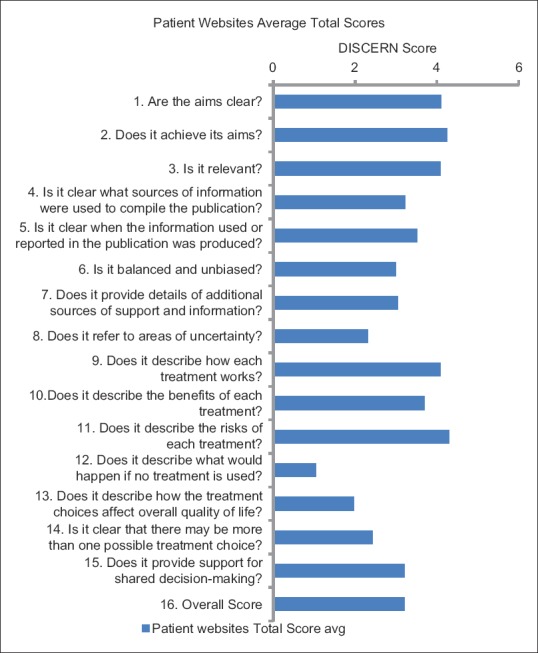

A total of 110 websites were identified and recorded for all combined 11 search terms used. The mean scores of both assessors for each component of the DISCERN model for all 110 combined patient-searched websites are shown in Figure 1. This resulted in a mean total DISCERN score of 3.21 out of a 5-point scale for all 110 websites combined. Figure 2 summarizes the mean total DISCERN score according to each searched biologic agent separately. Total scores of all 10 websites for each searched biologic agent ranged from lowest at 2.93 (for Entyvio) to highest at 3.38 (for Ustekinumab).

Figure 1.

Mean scores between both assessors for each component of the DISCERN model for all patient-searched websites

Figure 2.

Mean total DISCERN score according to each searched biologic agent

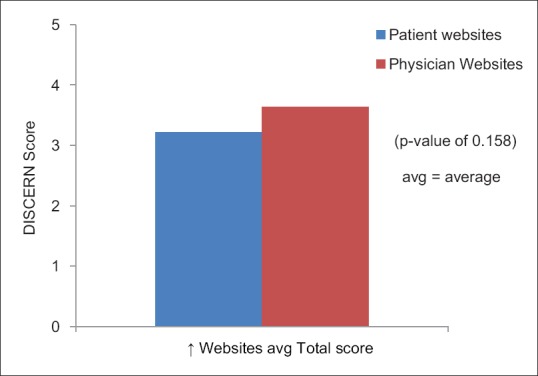

Regarding the secondary objective, which was to compare the total DISCERN scores of websites commonly visited by patients with the physician-referenced reputable websites, the results are summarized in Figure 3. The mean total DISCERN score for all the patient-searched websites was 3.21 compared with a mean score of 3.63 for the physician-referenced websites, which was not statistically significant (P = 0.158; 95% CI = −1.0090 to +0.1661).

Figure 3.

Average total DISCERN scores of patient-searched websites compared with physician-referenced websites

Table 1 summarizes the three highest rated websites for each searched biologic agent, where the mean scores ranged from 3.64 to 4.13. The overall top-rated five categorical website sources from all searched biologic agents are summarized in Table 2, with the mean total DISCERN scores ranging from 3.8 to 4.13 for these websites.

Table 1.

The three highest rated websites for each searched biologic agent

Table 2.

The overall five top-rated websites from all searched biologic agents

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the quality of information of websites that may be used by patients in obtaining information related to the biologic agents used in the treatment of IBD. Most of the DISCERN model overall scores of the websites were judged to be either average or above average. Examining the DISCERN model more closely, most of the lowest scored areas (scoring 2.5 and less overall) were regarding the lack of discussion of uncertainty, not describing what would happen if no treatment is used, failing to describe the effect on the quality of life, and failing to describe that more than one possible treatment choice exists. The first and last points are likely due to the fact that many of the websites were manufacturer-based, and thus, biased toward one specific agent or brand. These results are similar to those from a recently published study that reported that private companies with commercial interest and investment authored more than 65% of searched websites.[19] It is important to note that this was evidently the opposite for physician-recommended unbiased websites with these two areas scoring above average to excellent. It was surprising, however, to see that the overall scores were not significantly different between the commonly patient-searched websites and the physician-recommended sites. This gap narrows further and may in fact favor some of the patient-searched over physician-recommended websites when considering the five highest scoring websites from the collectively pooled data. The highest ranked patient-searched website was “ema.europa.eu” scoring 4.13. This was only second overall to the highest ranked physician-recommended website, which was “Crohn's and Colitis Foundation” scoring 4.7. Previously published studies have estimated that more than 90% of patients use the Internet for health-related information, which is why it is important to ensure that high-quality websites are available for patients to explore.[6] Similar to this study, many other publications evaluated the quality of the information of various IBD websites using the DISCERN model and found a wide-range of score variability. One study published in 2009 showed that 43% of websites that were evaluated had scores that were above average, while 57% were evaluated as fair or poor.[20] Similar to the results of our study, the quality of the information varied widely among the different websites evaluated.[20] This was again re-demonstrated in a systematic review in 2010 with marked variation in the assessment of the quality of information available to patients on the Internet pertaining to IBD treatment options.[21] Some of these studies used other models to evaluate websites in addition to the DISCERN model, including Data Quality Score, Global Quality Score, and Drug Category Quality Score.[21] Given the variability among scoring models, it is not clear which model is most accurate in assessing the quality of information-based websites on the Internet.[21]

Results of various published studies reported that two thirds of patients trust the Internet for medical information.[6,7] It is almost unavoidable having patients explore the Internet and attempting to seek information pertaining to their medical condition or treatment, which may influence their decision making. One benefit of this study is the use of a validated method to highlight some of the higher quality websites (consistent among both assessors) that physicians should choose to direct patients to, when exploring the Internet.

However, this study has a few limitations that are crucial to this discussion. Although we looked at the first 10 websites for each agent meeting the inclusion criteria on a Google search, this website “rank” changes from day to day based on “popularity” on the search engine and the type of search engine used. Therefore, it may not capture or reflect the true sense of the “most commonly” visited websites by patients. In addition to that, given that Internet websites are very dynamic and are modified quiet frequently, the DISCERN score conclusions we made are only based on the quality of the site at the time of our search and evaluation. Similarly, the four physician-recommended websites evaluated here may not reflect the complete list of recommended websites by various other physicians or IBD institutions.

The DISCERN model used in this study has been validated and has some key points to consider as guidance when evaluating each question in the model. Although it may not be overtly significant for the overall score, evaluating each section remains partially subjective. This is evident by the minor evaluator variability we allowed (a variability score of ± 1 on the DISCERN scoring model) in scoring each question of the model for each of the websites. Considering this interevaluator variability as an agreement may not be a valid process in evaluating websites and may have impacted our results.

CONCLUSIONS

The Internet as a source of information for commonly prescribed biologic agents in the treatment of IBD can sometimes provide educational opportunities, but can also misguide patients. The combined quality of Internet web-based resources used for each drug was fairly consistent in scoring intermediate to slightly above average with no significant superiority of the combined overall scores of the physician-recommended websites. However, physicians can direct and guide patients toward certain higher quality websites that consistently scored slightly better overall, in order to reduce the risk of misguidance of patients while exploring poor quality websites on the Internet. These higher quality websites include “ema.europa.eu” and “Crohn's and Colitis Foundation.” The Internet in today's information age is a broadly variable resource available at the click of a finger. It is crucial that physicians take this resource access opportunity in directing and guiding their patients accordingly so that they are not misinformed. Targeting those websites with high overall quality may help in educating patients and empowering them to make appropriate informed decisions with respect to their IBD treatment. However, we still need further studies to develop more standardized methods in evaluating resources used in the effective education of our patients.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

Nilesh Chande has received consulting or speaking fees from AbbVie, Janssen, Takeda, Lupin, Ferring, Pendopharm, Allergan, Pfizer, and Shire.

REFERENCES

- 1.Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, Ghali WA, Ferris M, Chernoff G, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:46–54. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shivashankar R, Tremaine WJ, Harmsen WS, Loftus EV., Jr Incidence and Prevalence of Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis in Olmsted County, Minnesota From 1970 Through 2010. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:857–63. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.10.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kappelman MD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Kleinman K, Ollendorf D, Bousvaros A, Grand RJ, et al. The prevalence and geographic distribution of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1424–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.ITU World Telecommunication/ICT Indicators [database online] International Telecommunications Union. World Telecommunication/ICT Indicators database 2013 17th Ed. Updated July 5. 2013. [Last accessed on 2017 Sep 16]. Available at: http://www.itu.int/en/ITU.D/Statistics/Documents/statistics/2013/ITU_Key_ 2005-2013_ICT_data.xls .

- 5.Veenhof B, McKeown L. 2010 Canadian Internet use survey [Statistics Canada Web site]. January 9. 2013. [Last accessed on 2017 Sep 18]. Available at: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/110525/dq110525b-eng.htm .

- 6.Greveson K, Shepherd T, Hamilton M, Murray CD. PTH-044 A Single-centre Pilot Study Examining Internet Use For Health Related Information Among Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gut. 2014;63:A228. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alarcón O, Baudet JS, Sánchez Del Río A, Dorta MC, De ML, Socas MR, et al. Internet use to obtain health information among patients attending a digestive diseases office. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;29:286–90. doi: 10.1157/13087467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Angelucci E, Orlando A, Ardizzone S. Internet use among inflammatory bowel disease patients: An Italian multicenter survey. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:1036–41. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328321b112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cima RR, Anderson KJ, Larson DW, Dozois EJ, Hassan I, Sandborn WJ, et al. Internet use by patients in an inflammatory bowel disease specialty clinic. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:1266–70. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Panes J, Sans M, Soriano A, Piqué JM. Frequent Internet use among Catalan patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;25:306–309. doi: 10.1016/s0210-5705(02)79024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halpert A, Dalton CB, Palsson O, Morris C, Hu Y, Bangdiwala S, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome patients' ideal expectations and recent experiences with healthcare providers: A national survey. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:375–83. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0855-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Connor JB, Johanson JF. Use of the Web for medical information by a gastroenterology clinic population. JAMA. 2000;284:1962–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.15.1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teriaky A, Tangri V, Chande N. Use of internet resources by patients awaiting gastroenterology consultation. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2015;26:49–52. doi: 10.5152/tjg.2015.6043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Charnock D, Shepperd S, Needham G, Gann R. DISCERN: An instrument for judging the quality of written consumer health information on treatment choices. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53:105–11. doi: 10.1136/jech.53.2.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Griffiths KM, Christensen H. Website quality indicators for consumers. J Med Internet Res. 2005;7:e55. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7.5.e55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rees CE, Ford JE, Sheard CE. Evaluating the reliability of DISCERN: A tool for assessing the quality of written patient information on treatment choices. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;47:273–5. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(01)00225-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charnock D, Shepperd S. Quick reference guide to the DISCERN criteria [DISCERN online Web site]. June. 2008. [Last accessed on 2017 Jul 10]. Available at: http://www.discern.org.uk .

- 18.Streiner DL, Norman GR, Cairney J. Health measurement scales: A practical guide to their development and use. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sacchi M, Yeung TM, Spinelli A, Mortensen NJ. Assessment of the quality of patient-orientated internet information on surgery for ulcerative colitis. Colorectal Dis. 2015;17:511–4. doi: 10.1111/codi.12870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van der Marel S, Duijvestein M, Hardwick JC, van den Brink GR, Veenendaal R, Hommes DW, et al. Quality of web-based information on inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1891–6. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Langille M, Bernard A, Rodgers C, Hughes S, Leddin D, van Zanten SV. Systematic review of the quality of patient information on the internet regarding inflammatory bowel disease treatments. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:322–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]