Abstract

Objectives

(1) To assess the levels of impoverishment and catastrophic expenditure due to out-of-pocket (OOP) payments for antenatal care (ANC) and delivery care in Yangon Region, Myanmar; and (2) to explore the determinants of impoverishment and catastrophic expenditure.

Design, setting and participants

A community-based cross-sectional survey among women giving birth within the past 12 months in Yangon, Myanmar, was conducted during October to November 2016 using three-stage cluster sampling procedure.

Outcome measures

Poverty headcount ratio, normalised poverty gap and catastrophic expenditure incidence due to OOP payments in the utilisation of ANC and delivery care as well as the determinants of impoverishment and catastrophic expenditure.

Results

Of 759 women, OOP payments were made by 75% of the women for ANC and 99.6% for delivery care. The poverty headcount ratios after payments increased to 4.3% among women using the ANC services, to 1.3% among those using delivery care and to 6.1% among those using both ANC and delivery care. The incidences of catastrophic expenditure after payments were found to be 12% for ANC, 9.1% for delivery care and 20.9% for both ANC and delivery care. The determinants of impoverishment and catastrophic expenditure were women’s occupation, number of household members, number of ANC visits and utilisation of skilled health personnel and health facilities. The associations of the outcomes with these variables bear both negative and positive signs.

Conclusions

OOP payments for all ANC and delivery care services are a challenge to women, as one of fifteen women become impoverished and a further one-fifth incur catastrophic expenditures after visiting facilities that offer these services.

Keywords: impoverishment, catastrophic expenditure, out-of-pocket payment, antenatal care, delivery care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study measured impacts of out-of-pocket (OOP) payments for antenatal and delivery care on levels of impoverishment and catastrophic expenditure in Myanmar, one of the few studies on this issue in a low-income country. Other determinants of impoverishment and catastrophic expenditure were also analysed using logistic regression and found to be important.

Multistage sampling design and the use of adjusted SEs in the analysis minimised the sampling bias and provided reliable and policy relevant estimates.

The data on social determinants of OOP payments for antenatal and delivery care were also collected and the evidence from their analysis has been incorporated in this study.

The data on expenditures of antenatal and delivery care are based on women’s self-reported experiences during service utilisation, and may thus contain some recall bias.

Household annual incomes as well as OOP payments for healthcare services are self-reported and may suffer from over-reporting or under-reporting.

Introduction

Worldwide, nearly 830 women die during pregnancy and childbirth every day, with most of them living in poor households having limited proper maternal healthcare.1 Increasing utilisation of maternal health services is one of the targets of Sustainable Development Goal 3.2 Poverty or financial problems are the major barrier to accessibility and utilisation of antenatal care (ANC) and delivery by skilled birth attendants.3 Even though the economic indicators of most countries in 2015 were better than in earlier years, there are still some countries which face financial barriers leading to worse health outcomes.2

Low socioeconomic level or high healthcare expenditures can lead to financial burdens, either impoverishment or catastrophic expenditure, which use different analyses and thresholds of burden.4 5 Financial burdens from utilisation of maternal healthcare have been previously reported in some African and Asian countries such as Ghana, Nepal, Bangladesh and India.6–9 In Myanmar, out-of-pocket (OOP) payments for health services were high in public and private health facilities and accounted for more than 80% of total health expenditures of the country in 2012.10 Only one study of OOP payments for maternal healthcare in Myanmar with percentage of catastrophic health expenditures in Myanmar was found11; therefore, the evidence on impoverishment and catastrophic payments of ANC and delivery care and their determinants in Myanmar to date is limited.

Different countries have introduced different strategies to reduce financial burdens related to accessing necessary healthcare during pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum period.12 Providing free maternal health services has been implemented in some low-income countries, but various studies have found low utilisation of these services as well as high maternal mortality and morbidity.7 13 14 A study in Thailand found improvement of maternal health outcomes 5 years after the implementation of a universal coverage scheme with health finance reform.15 Although some countries have begun to offer free health services or health insurance, the achievements in terms of reducing financial burdens remain limited.12

Similarly, Myanmar has begun a programme providing free essential drugs and healthcare for maternal health services in both public facility-based and primary healthcare settings in recent years, but OOP payments while accessing these services have been reported.10 16 17 In addition, reports on the actual financial burden in terms of impoverishment and catastrophic expenditure due to OOP payments are limited.11 Understanding the determinants of financial burden in using maternal health services is useful to identify the nature of the OOP payment situation and whether any determinants are modifiable or require policy improvement.14 18 19 This study aimed to assess the levels of impoverishment and catastrophic expenditure due to OOP payments for ANC and delivery care in Yangon Region, Myanmar, and explore the determinants of impoverishment and catastrophic expenditure.

Methods

Study design, participants and sampling method

The study was based on a community-based cross-sectional survey conducted in Yangon Region of Myanmar during October and November 2016. According to the 2014 census report, Yangon Region had the largest population among the regions of Myanmar.20 The study recruited women of reproductive age (15–49 years) with a history of birth within the previous 12 months who were residents of the study area. Those who had mental retardation or serious illness were excluded. The required sample size for the first objective was calculated using the one-proportion formula based on a rate of 9% of pregnant women with catastrophic expenditure due to OOP payments in utilisation of delivery care from a previous study.11 21 With a precision of 4%, type I error of 1%, non-response rate of 10% and design effect of 2, at least 750 women were required.

A three-stage cluster sampling was used to select eligible persons. For stage 1, purposive selection of two districts among the four districts of Yangon Region which covered both urban and rural populations was done. There were a total of 235 wards and 610 villages in these two districts. ‘Wards’ and ‘villages’ refer to urban and rural populations, respectively.22 For stage 2, sixteen wards and 16 villages were randomly selected from all of the wards and villages. Households were selected regarding the number of households and the ratio of urban to rural population size in the districts considering proportional probability sampling. For stage 3, we randomly selected women who had delivered within the past 12 months in each household from selected wards and villages. For households with more than one eligible woman, one woman was selected randomly.

Involvement of patients and the general public in the study

Women and household members and the public were not involved in the development of the research questions, in design of the fieldwork or in the recruitment of research assistants. The results reported in the paper were not disseminated to study participants.

Outcome and independent variables

The main outcome measures were the poverty headcount ratio, normalised poverty gap and catastrophic expenditure incidence due to OOP payments in the utilisation of ANC and delivery care. OOP payments included the expenses of all related healthcare services received during ANC and delivery care, namely hospital costs/investigation fees, drugs, consultation fees, food/living/transportation payments and other costs. The OOP payments were calculated for ANC and delivery care and then summed as total OOP payments for care. OOP payments for ANC were counted as the sum of all ANC visits. Impoverishment was defined as a situation where a household fell below the international poverty line (US$1.9 in Purchasing Power Parity-PPP) after paying for maternal healthcare services.23 24 Catastrophic expenditure was defined as OOP payment for maternal healthcare services exceeding a threshold of 10% of a household’s annual income.25

Independent variables included background characteristics of the women and their husbands and household information, accessibility of health services, characteristics of ANC and delivery care and details of services provided. Household annual income was classified into ≤US$1275 or >US$1275 according to gross domestic product per capita of Myanmar from the World Bank 2016 data. The household annual incomes were recorded in Myanmar kyats and converted to US$ using the exchange rate of US$1 equal to 1362.63 kyats. The information pertaining to accessibility to health services included availability of a health centre, distance as measured in walking minutes (number of walking minutes from the woman’s house to a formal health centre) and types of transportation (women who used any transport to visit a health centre). Characteristics of ANC and delivery care included complications during pregnancy and childbirth and number of ANC visits. Details of services provided included health personnel, place of care, affordability and OOP payments.

Data collection

Before the data collection began, 12 research assistants were trained in a 2-day training workshop on how to conduct the interviews and check the information for data completeness. The lists of women were obtained from the township health departments and local authorities. The eligible women were visited at their home by the research team at the woman’s convenience. After the study was explained and a consent form signed, the women were interviewed by the principal investigator and researchers using a pretested structured questionnaire in a private area. Each completed interview was checked promptly for any errors and edited if required. All questionnaires were reviewed at the end of each day for accuracy of the data obtained.

Statistical analysis

After the data collection was completed, EpiData V.3.1 was used to record the data in a double entry system, and R V.3.4.2 was used for data analysis.26 27

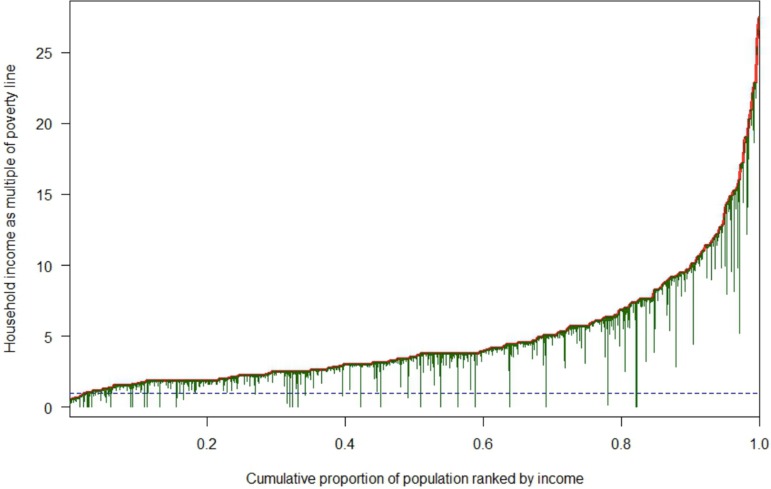

We considered the maternal healthcare services from ANC to delivery care and the prepayment period was counted at one point before using the ANC, thus the prepayment headcount ratio and normalised poverty gap for ANC and delivery care were the same. Prepayment and postpayment headcount ratios were measured by the proportion of households having household annual income below the poverty line before and after the women used the ANC and delivery care, respectively. The average of the relative income shortfall of the poor from the poverty line is the normalised poverty gap. A Pen’s parade graph between household incomes as a multiple of the poverty line (y axis) with the cumulative proportion of the population ranked by household income (x axis) was plotted to show the number of non-poor households which became poor after OOP for pregnancy expenses as indicated by the vertical lines below the poverty line. Catastrophic expenditure was measured by the incidence and intensity. Incidence was calculated by the proportion of households who faced catastrophic expenditure due to OOP payments for ANC or delivery care. Intensity was calculated by the proportion of OOP payments for ANC and delivery care exceeding the 10% threshold of the household’s annual income.25 28

Data on dependent variables (impoverishment and catastrophic expenditures) and on independent variables (the determinants) were collected and analysed using multiple logistic regression, with sampling weights being applied to adjust for the cluster sampling design. The first-stage adjustment weight was calculated by dividing the total number of wards and villages in each district by the selected number of wards and villages. The second-stage weight was calculated by dividing the total number of women by the selected number of women in each ward and village. The final-stage weight was calculated by multiplying the first-stage and second-stage weights.29 The adjusted ORs and 95% CIs were used for presenting the final estimates. A p value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

A total of 759 women were included in the study. More than two-thirds of the women lived in an urban area. Half of the women were aged 25-34 years and 71% were housewives. More than two-thirds of their husbands had above primary school-level education and 60% of them worked as daily wage earners. Most of the households had less than five household members and 89% of them had an annual household income above US$1275, and 60.3% of the households had debt. More than 80% of the women said that a health centre was available for them to get ANC services within 30 min walking distance. Only 21.2% of the women had less than four ANC visits and 15% and 23% of them faced complications during pregnancy and childbirth, respectively (table 1).

Table 1.

Background characteristics of women and their husbands, household information, accessibility of health services and characteristics of ANC and delivery care (n=759)

| Characteristic | n (%) |

| Women’s characteristics | |

| Place of residence | |

| Urban | 542 (72.4) |

| Rural | 217 (28.6) |

| Age (years) | |

| 15–24 | 215 (28.3) |

| 25–34 | 376 (49.5) |

| 35–49 | 168 (22.1) |

| Occupation | |

| Housework | 539 (71) |

| Any job | 220 (29) |

| Husbands’ characteristics | |

| Education | |

| Primary school and lower | 242 (31.9) |

| More than primary school | 517 (68.1) |

| Occupation | |

| Daily wage earner | 455 (59.9) |

| Other | 304 (40.1) |

| Household characteristics | |

| Number of household members | |

| >5 | 276 (38.4) |

| 3–5 | 483 (63.6) |

| Household annual income | |

| ≤US$1275 | 83 (10.9) |

| >US$1275 | 676 (89.1) |

| Household debt | |

| No | 301 (39.7) |

| Yes | 458 (60.3) |

| Accessibility of health services | |

| Availability of health centre | |

| No | 123 (16.2) |

| Yes | 636 (83.8) |

| Walking distance (min) | |

| >30 | 76 (10) |

| ≤30 | 683 (90) |

| Type of transportation | |

| Car | 79 (10.4) |

| Motorcycle | 172 (22.7) |

| Walking | 406 (53.3) |

| Other | 102 (13.4) |

| Characteristics of ANC and delivery care | |

| Number of ANC visits | |

| 1–3 | 161 (21.2) |

| 4–6 | 262 (34.5) |

| >6 | 336 (44.3) |

| Complication during pregnancy | |

| No | 645 (85.0) |

| Yes | 114 (15.0) |

| Complication during birth | |

| No | 584 (76.9) |

| Yes | 175 (23.1) |

ANC, antenatal care.

Table 2 shows the details of the services used and payments of the women for ANC and delivery care. More than half (56.4%) met community health personnel for ANC followed by specialists (22.5%) and doctors/nurses (21.1%). Similar numbers had delivery by community health personnel (35.4%) or doctors/nurses (35.2%), with the rest by specialists (29.4%). Most of the women used public facilities for ANC (78%) and delivery care (65%). Almost all of the women said they could afford the cost of each ANC visit and half could afford the cost of delivery care. OOP payments were made by 75% of the women for ANC and by 99.6% for delivery care. Hospital costs/investigation fees were highest for ANC and delivery care. Cost per each ANC visit was lower, but the total cost for all ANC visits was higher than the total cost of delivery care.

Table 2.

Details of services used and payments of the women for ANC and delivery care (n=759)

| Antenatal care | Delivery care | |

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Health personnel | ||

| Community health personnel | 428 (56.4) | 269 (35.4) |

| Specialists | 171 (22.5) | 223 (29.4) |

| Doctors/nurses | 160 (21.1) | 267 (35.2) |

| Place of care | ||

| Public facilities | 592 (78) | 493 (65) |

| Private facilities | 167 (22) | 266 (35) |

| Affordability (per visit/delivery) | ||

| No | 26 (3.4) | 338 (44.5) |

| Yes | 733 (96.6) | 421 (55.5) |

| Out-of-pocket payments | ||

| No | 186 (24.5) | 3 (0.4) |

| Yes | 573 (75.5) | 756 (99.6) |

| (n=573) | (n=756) | |

| Total costs of care | 31.7 (0–12072.2) | 84.4 (0–2305.1) |

| Total out-of-pocket payments of care | 31.7 (0–10633.8) | 73.4 (0–1541.1) |

| Categories of out-of-pocket payments (per visit/delivery) | ||

| Hospital cost/investigation fees | 0.73 (0–80.8) | 7.34 (0–1247.6) |

| Drugs | 0 (0–40.4) | 0 (0–587.1) |

| Consultation fees | 0 (0–23.9) | 0 (0–440.3) |

| Food/travel/living cost | 0.57 (0–73.4) | 2.94 (0–1027.4) |

| Other expenses | 0 (0–29.4) | 0 (0–220.2) |

| Sum of costs | 4.8 (0–759.6) | 73.4 (0–1541.1) |

ANC, antenatal care.

Table 3 shows the changes in impoverishment due to OOP payments for ANC and delivery care. The poverty headcount ratio at prepayment was 2.4%. The poverty headcount ratio considering the postpayment and prepayment for women using both ANC and delivery care showed that poverty increased to 6.1% after service utilisation with the decomposition of 4.3% for ANC and 1.3% for delivery care. The increase in the normalised poverty gap showed a similar trend, with 1.25% for ANC and 0.49% for delivery care services. The individual prepayment and postpayment incomes associated with OOP of both ANC and delivery care are shown in the Pen’s parade (figure 1). Overall, the OOP payments for ANC and delivery care lead to poverty regardless of household income levels. Table 4 presents the evidence on catastrophic expenditures due to OOP payments for ANC and delivery care. The incidences for households incurring catastrophic expenditure due to OOP payments for ANC, delivery care and overall for ANC and delivery care combined were 12%, 9.1% and 20.9%, respectively. Intensities of catastrophic expenditures were greater among women using ANC services than for those using delivery care.

Table 3.

Impoverishment due to OOP payments for ANC and delivery care (n=757)

| Before using ANC or delivery care | Impoverishment due to OOP payments (%) | ||||||

| Antenatal care | Delivery care | Overall antenatal and delivery care | |||||

| Prepayment | Postpayment | Change | Postpayment | Change | Postpayment | Change | |

| Poverty headcount ratio | 2.4 | 6.7 | 4.3 | 3.7 | 1.3 | 8.5 | 6.1 |

| Normalised poverty gap | 0.01 | 1.26 | 1.25 | 0.50 | 0.49 | 1.40 | 1.39 |

ANC, antenatal care; OOP, out-of-pocket.

Figure 1.

Pen’s parade of prepayment and postpayment incomes of overall antenatal and delivery care.  prepayment income;

prepayment income;  postpayment income;

postpayment income;  income-based poverty line.

income-based poverty line.

Table 4.

Catastrophic expenditures due to OOP payments for ANC and delivery care (n=757)

| Catastrophic expenditures due to OOP payments | Antenatal care | Delivery care | Overall antenatal and delivery care |

| Incidence (%) | 12.0 | 9.1 | 20.9 |

| Intensity (%) | 6.1 | 1.7 | 9.2 |

ANC, antenatal care; OOP, out-of-pocket.

The determinants of impoverishment and catastrophic expenditure due to OOP payments for ANC and delivery care are shown in table 5. Housewives, women who had lower numbers of household members, and those who used more ANC services and those who were delivered by specialists or had ANC at private health facilities were more likely than their counterparts to face impoverishment and/or catastrophic expenditures due to OOP payments. Women who used delivery care at private facilities had elevated ORs for impoverishment, but notably not for incurring catastrophic expenditures.

Table 5.

Determinants of impoverishment and catastrophic expenditure due to OOP payments for overall ANC and delivery care (n=757)

| Characteristic | Impoverishment | Catastrophic expenditure |

| Adjusted OR (95% Cl) | Adjusted OR (95% Cl) | |

| Woman’s occupation | ||

| Other (ref) | 1 | 1 |

| Housewife | 4.81 (1.91 to 12.12)*** | 2.18 (1.16 to 4.10)* |

| Number of household members | ||

| >5 (ref) | 1 | 1 |

| 3–5 | 7.13 (2.77 to 18.33)*** | 7.82 (4.41 to 13.89)*** |

| Number of ANC visits | ||

| 1–3 (ref) | 1 | 1 |

| 4–6 | 1.26 (0.35 to 4.52) | 2.06 (0.99 to 4.31) |

| >6 | 5.73 (1.90 to 17.26)** | 5.63 (2.96 to 10.70)*** |

| Health personnel for delivery care | ||

| Community health personnel (ref) | 1 | 1 |

| Specialists | 2.97 (1.14 to 7.76)* | 4.83 (2.24 to 10.44)*** |

| Doctors/nurses | 2.22 (0.78 to 6.33) | 3.45 (1.64 to 7.27)** |

| Place of antenatal care | ||

| Public facilities (ref) | 1 | 1 |

| Private facilities | 2.46 (1.14 to 5.32)* | 2.42 (1.40 to 4.17)** |

| Place of delivery care | ||

| Public facilities (ref) | 1 | |

| Private facilities | 3.29 (1.41 to 7.70)** |

*P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

ANC, antenatal care; OOP, out-of-pocket.

Discussion

Approximately one-fifteenth and one-fifth of women using both ANC and delivery care in the study area faced impoverishment or catastrophic expenditure due to OOP payments. Women with a higher number of household members or increased use of ANC visits or who accessed specialists or private services were more likely to face impoverishment or catastrophic expenditure.

Even though free maternal healthcare services are nationally available, at least three-fourths of the women incurred OOP payments, which was the same as a previous study in Myanmar conducted in 2015.11 This finding was also similar to previous studies from India in 200418 and Nigeria in 2010,13 although the maternal health services considered and the methods of OOP measurement were different. Similarly, a study of three African countries where free delivery care was available found that 90% of the women still paid some amount of OOP for their direct medical expenses.30 A possible explanation might be due to the existence of high informal payments or some expenses not being covered by health insurance.10 11 13 18 30 The need to turn to OOP payments has been shown to influence the utilisation of maternal health services and maternal mortality.31 Importantly, another study reported that high OOP payments for maternal healthcare also lead households to impoverishment and catastrophic expenditure.4

The impoverishment rates in published studies vary depending on the methods used to measure healthcare expenditures and the poverty line thresholds used for calculating impoverishment. Our study used the international poverty line in 2011 of US$1.9 per day, but a study from Nepal used the international poverty line in 2005 of US$1 per day and reported the poverty headcount ratio of 17% after the use of institutional delivery8 which was higher than that of our study. In contrast, a study in India used the local poverty line and found higher impoverishment due to maternal healthcare expenditure than the findings of our study.32 Although Yangon Region is the most developed region in Myanmar, a lot of non-poor households face impoverishment and deep poverty which could be explained by high maternal healthcare payments without a compensation scheme.10 20 Two studies from India using data from 2004 and 2015 found that the poverty headcount ratio for maternal healthcare expenditures declined after introducing free services for delivery care in 2015.32 33

Likewise, variations in the incidence of catastrophic expenditure due to maternal healthcare expenditures depend on the different maternal services measured, whether household income or capacity to pay is considered, and the catastrophic expenditure threshold used. One-fifth of women faced catastrophic expenditure due to OOP payments for ANC and delivery care in our study, which was higher than an earlier study from Myanmar in 2015. This may be because the previous study measured catastrophic expenditure based only on OOP payments for delivery care, not ANC, and also only direct and indirect medical costs, not other costs or productivity loss.11 Higher incidences of catastrophic expenditure due to OOP payments were reported in India and Ethiopia because poorer women were included and all ANC, delivery and postnatal care services were considered.32 34 Prior studies from Africa and Bangladesh concluded that more than one-third of women faced catastrophic expenditure due to OOP payments for emergency obstetric care because they were poor and were required to pay for drugs.35–37

Woman’s occupation was associated with impoverishment and catastrophic expenditure due to OOP payments but a previous study could not identify a direct association between occupation and impoverishment and catastrophic expenditure. The significant association between woman’s occupation, impoverishment and catastrophic expenditure found in our study could be explained by woman’s low levels of employment. Lower number of household members was also associated with the impoverishment and catastrophic expenditure in our study. This finding was different from a previous study from India,19 which could be explained by the lower sharing of financial resources among household members of the study participants. The finding of higher rates of catastrophic expenditures in women with a higher number of ANC visits was also similar to a study in India which included women with low economic status.38 Other previous studies have found that women who used a nearby health centre or facilities having specialists and private facilities for ANC and delivery care where health insurance was not available were more likely to have impoverishment and catastrophic expenditures.14 18 19 31 38 39

Only one previous study from Myanmar in rural areas of a township in Ayeyarwady Region measured catastrophic health expenditures resulting from maternal healthcare.11 Our study included both rural and urban areas of Yangon Region, and provides important information on these factors for policymakers to help them consider financial burdens leading to impoverishment or catastrophic expenditures.

The study had some limitations. First, this was a cross-sectional study, thus the causal relationship between the determinants and level of impoverishment and catastrophic expenditures due to OOP payments for ANC and delivery care could not be firmly identified. Second, household annual income and payments for healthcare services were self-reported, therefore there may have been over-reporting or under-reporting. Third, the payment of total ANC used the payment of last ANC visit and then multiplied by the total number of all visits. Fourth, recall bias might have occurred due to data gathering through retrospective interviews. However, we included only women within 12 months of delivery to minimise the recall bias. Finally, the socioeconomic status of the people in the Yangon Region is better than in other regions; therefore, the findings of this study are not likely representative of the entire country.

Conclusions

High OOP payments for utilisation of ANC and delivery care in the Yangon Region of Myanmar resulted in one-fifteenth of the women becoming impoverished and one-fifth suffering a catastrophic expenditure. Women with few household members, or with a large number of ANC visits, or who had been attended by specialists or had used private services were more likely than other women to face impoverishment or catastrophic expenditures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was part of a doctoral thesis in Epidemiology of the first author at Prince of Songkla University in Thailand. We thank the Ministry of Health and Sports and Regional Department of Yangon for their permission and support during the data collection phase of this work.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the concept and design of the study. ANMM and TL participated in data collection, data analysis, interpretation of data and preparation of the draft manuscript. TTH, MMW, JS and EB also assisted with interpretation of data and commented on the draft manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad) funded the project ‘Health and Sustainable Development in Myanmar–Competence building in public health and medical research and education, MY-NORTH’, through the NORHED programme: Norad: 1300650, MMR-13/0049 NORHED, UiO: 211782.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Ethical clearances for the study were obtained from the Ethics Review Committee of Prince of Songkla University, Thailand, the Department of Medical Research, Myanmar, and the Norwegian National Research Ethics Committee (NSD), Norway.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available. Original data without identity can be provided on request after the Ethics Review Committee of Prince of Songkla University is informed and provides their approval.

References

- 1. WHO. WHO fact sheet on maternal mortality. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2. WHO. Health in 2015: from MDGs, millennium development goals to SDGs, sustainable development goals. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3. UNICEF. Monitoring and situation of children and women. New York: United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Saksena P, Hsu J, Evans DB. Financial risk protection and universal health coverage: evidence and measurement challenges. PLoS Med 2014;11:e1001701 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. WHO, World Bank. Tracking universal health coverage. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Skordis-Worrall J, Pace N, Bapat U, et al. . Maternal and neonatal health expenditure in Mumbai slums (India): a cross sectional study. BMC Public Health 2011;11:150 10.1186/1471-2458-11-150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dalaba MA, Akweongo P, Aborigo RA, et al. . Cost to households in treating maternal complications in northern Ghana: a cross sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:34 10.1186/s12913-014-0659-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gartoulla P, Liabsuetrakul T, Chongsuvivatwong V, et al. . Ability to pay and impoverishment among women who give birth at a University Hospital in Kathmandu, Nepal. Glob Public Health 2012;7:1145–56. 10.1080/17441692.2012.733719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rahman M, Rob U, Noor FR, et al. . Out-of-pocket expenses for maternity care in rural Bangladesh: a public-private comparison. Int Q Community Health Educ 2012;33:143–57. 10.2190/IQ.33.2.d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. World Bank. Myanmar: public expenditure review 2015. Washington D.C: World Bank, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Han WW, Saw S, Einda HMT, et al. . Out of pocket expenditure on maternal and child health care services among rural households in Dedaye township, Myanmar. Myanmar Med J 2017;59:37–49. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Borghi J, Ensor T, Somanathan A, et al. . Mobilising financial resources for maternal health. Lancet 2006;368:1457–65. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69383-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kalu-Umeh NN, Sambo MN, Idris SH, et al. . Costs and patterns of financing maternal health care services in rural communities in Northern Nigeria: Evidence for designing national fee exemption policy. Int J MCH AIDS 2013;2:163–72. 10.21106/ijma.21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Goli S, Pradhan J, Rammohan A, et al. . High spending on maternity care in India: what are the factors explaining it? PLoS One 2016;11:e0156437 10.1371/journal.pone.0156437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Limwattananon S, Tangcharoensathien V, Prakongsai P. Equity in maternal and child health in Thailand. Bull World Health Organ 2010;88:420–7. 10.2471/BLT.09.068791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Latt NN, Myat C S, Htun NM, et al. . Healthcare in Myanmar. Nagoya J Med Sci 2016;78:123–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Myanmar Ministry of Health and Sports. Myanmar national health plan 2017 - 2021. Nay Pyi Taw: Ministry of Health and Sports, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kerketta S. Out of pocket expenditure on utilization of ante-natal and delivery care services in India: analysis based on NSSO 60th round. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol 2015;4:1704–9. 10.18203/2320-1770.ijrcog20151126 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Leone T, James KS, Padmadas SS. The burden of maternal health care expenditure in India: multilevel analysis of national data. Matern Child Health J 2013;17:1622–30. 10.1007/s10995-012-1174-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Myanmar Ministry of Immigration and Population. Yangon region census report. Nay Pyi Taw: Ministry of Immigration and Population, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 21. WHO. Sample size determination in health studies, a practical manual. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Myanmar Ministry of Home Affairs. Myanmar administrative structure. Nay Pyi Taw: Ministry of Home Affairs, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 23. WHO. Distribution of health payments and catastrophic expenditures methodology. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bank W. Country poverty brief, Myanmar. Washington, D.C: World Bank, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 25. O’Donnell O, Ev D, Wagstaff A, et al. . Analyzing health equity using household survey data: a guide to techniques and their implementation. Washington, D.C: World Bank, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R foundation for statistical computing. 1.0.153 version. Vienna, Austria, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 27. EpiData entry. 3.1 version. Odense, Denmark, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wagstaff A, van Doorslaer E. Catastrophe and impoverishment in paying for health care: with applications to Vietnam 1993-1998. Health Econ 2003;12:921–33. 10.1002/hec.776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lumley T. Complex sampling. Washington, D.C: R. A John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Perkins M, Brazier E, Themmen E, et al. . Out-of-pocket costs for facility-based maternity care in three African countries. Health Policy Plan 2009;24:289–300. 10.1093/heapol/czp013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mohanty SK, Kastor A. Out-of-pocket expenditure and catastrophic health spending on maternal care in public and private health centres in India: a comparative study of pre and post national health mission period. Health Econ Rev 2017;7:31 10.1186/s13561-017-0167-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mukherjee S, Singh A, Chandra R. Maternity or catastrophe: a study of household expenditure on maternal health care in India. Health 2013;05:109–18. 10.4236/health.2013.51015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Prinja S, Bahuguna P, Gupta R, et al. . Coverage and financial risk protection for institutional delivery: how universal is provision of maternal health care in India? PLoS One 2015;10:e0137315 10.1371/journal.pone.0137315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Akalu T, Guda A, Tamiru M, et al. . Examining out of pocket payments for maternal health in rural Ethiopia: paradox of free health care un-affordability. Ethiop J Health Dev 2012;26:251–7. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shukla M, Kumar A, Agarwal M, et al. . Out-of-pocket expenditure on institutional delivery in rural Lucknow. Indian J Comm Health 2015;27:241–6. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Honda A, Randaoharison PG, Matsui M. Affordability of emergency obstetric and neonatal care at public hospitals in Madagascar. Reprod Health Matters 2011;19:10–20. 10.1016/S0968-8080(11)37559-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hoque ME, Dasgupta SK, Naznin E, et al. . Household coping strategies for delivery and related healthcare cost: findings from rural Bangladesh. Trop Med Int Health 2015;20:1368–75. 10.1111/tmi.12546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Goli S, Rammohan A, Out-of-pocket expenditure on maternity care for hospital births in Uttar Pradesh, India. Health Econ Rev 2018;8:5 10.1186/s13561-018-0189-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bonu S, Bhushan I, Rani M, et al. . Incidence and correlates of ’catastrophic' maternal health care expenditure in India. Health Policy Plan 2009;24:445–56. 10.1093/heapol/czp032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.