Abstract

Objectives

To analyse a potential association between surgical quality and time of day.

Design

A retrospective analysis of complete sets of quality forms filled out by the procuring and accepting surgeon on organs from deceased donors.

Setting

Procurement procedures in the Netherlands are organised per region. All procedures are performed by an independent, dedicated procurement team that is associated with an academic medical centre in the region.

Participants

In 18 months’ time, 771 organs were accepted and procured in The Netherlands. Of these, 17 organs were declined before transport and therefore excluded. For the remaining 754 organs, 591 (78%) sets of forms were completed (procurement and transplantation). Baseline characteristics were comparable in both daytime and evening/night-time with the exception of height (p=0.003).

Primary outcome measure

All complete sets of quality forms were retrospectively analysed for the primary outcome, procurement-related surgical injury. Organs were categorised based on the starting time of the procurement in either daytime (8:00–17:00) or evening/night-time (17:00–8:00).

Results

Out of 591 procured organs, 129 organs (22%) were procured during daytime and 462 organs (78%) during evening/night-time. The incidence of surgical injury was significantly lower during daytime; 22 organs (17%) compared with 126 organs (27%) procured during evening/night-time (p=0.016). This association persists when adjusted for confounders.

Conclusions

This study shows an increased incidence of procurement-related surgical injury in evening/night-time procedures as compared with daytime. Time of day might (in)directly influence surgical performance and should be considered a potential risk factor for injury in organ procurement procedures.

Keywords: surgery, risk management, transplant surgery, quality In health care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Quality of procurement is evaluated by two specialists; once by the procuring and once by the accepting surgeon. (+)

All procedures are performed by a dedicated, certified procurement team. This ensures a high standard of procurement quality. (+)

Selection bias in the timing of procurements is minimal because the planning is mainly logistical rather than medical. (+)

Injury is evaluated in a categorical way (yes/no) to analyse surgical performance in a broad sense. It avoids a loss of detailed information but limits a subanalysis on injuries leading to discarding organs.

Conclusions may be limited by the number of procured organs. (−)

Introduction

Night shifts have been shown to pose a higher risk for errors and self-injuries in several medical settings.1–4 A negative effect of night shifts might be caused by factors associated with fatigue and circadian rhythm5 and could also affect surgical performance. The potential relation between timing of procedures and surgical performance is, however, not clear. Studies have reported conflicting results6–10 and timing of procedures might therefore affect patients’ safety. The discussion on the topic has contributed to reforms in working hours for surgical residents in the USA as well as in Europe.

The lack of evidence for a causative relationship between fatigue-related factors and inferior performance in surgery is interesting considering the extensive amount of evidence in other fields.11 12 Although it might hold true that surgical performance is not affected by fatigue or time of day, it could also be a consequence of an insufficiently sensitive measurement of technical proficiency. To measure surgical performance, a negative clinical outcome in patients would be the most obvious endpoint. However, this has some limitations. First, a clinical endpoint might lead to a loss of detailed information because only severe intraoperative injuries are likely recognised for their clinical impact while minor injuries might be missed. Second, it is difficult to relate a specific surgical injury to a particular negative outcome in a patient because not all intraoperative injuries are noticed and negative outcomes are multifactorial and complex. A potential (minor) effect of time of day on surgical performance might therefore not be noticed when solely focusing on clinical outcome measures.

The Dutch digital feedback system on the quality of organ procurement offers an opportunity to analyse surgical performance in detail. We have previously analysed this dataset on procurement-related surgical injuries and found a high incidence of non-critical injuries. We did not find a significant difference between the non-critically injured and intact organs for 1-year graft survival.13 In this study, surgical injury is considered as a sensitive proxy of surgical performance. We hypothesise that a relationship is present between surgical performance and time of day.

Methods

Data

We obtained data from the Dutch Transplant Foundation on quality forms filled out from March 2012 until September 2013. It comprises two forms on each individual abdominal organ that is procured and accepted in The Netherlands. One form is filled out by the procuring surgeon after procurement and concurred or commented on by the accepting surgeon in the second form. Detailed information is registered on packaging, perfusion (time/volume/fluid), anatomy and possible injury of vessels or organs. In case of a discrepancy between the procuring and accepting surgeons, remarks of the accepting surgeon were considered leading. Pancreata procured for islet isolation and organs that were declined before transportation to the accepting centre were excluded. No ethical statement was required according to national ethical guidelines.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in the development of the research question or in the design of the study.

Statistical analysis

We accepted the time of cross-clamping the aorta and start of the cold perfusion as starting time of the procedure. For donation after circulatory determination of death (DCD), this is almost at the same time, but for donation after determination of brain death (DBD), this usually is 1–2 hours after skin incision. Vascular anatomy of organs was considered to be ‘normal’ for kidneys when a single artery and vein were observed. For livers and pancreata from the same donor, anatomy was considered normal according to the variable normal arterial anatomy (yes/no) in the liver quality form. In case information on the vascular anatomy was missing, it was considered to be normal (n=3, 0.5%). All organs were categorised in two groups: daytime (when procured between 8:00 and 17:00) or evening/night-time (when procured between 17:00 and 8:00). The incidence of injury was dichotomised (yes/no) and compared between both groups using univariate logistic regression with time of day as sole covariate. The analyses were adjusted for potential confounders, statistically significant in univariate analyses, and for known confounders reported in the literature. These factors include Body Mass Index (BMI) and donor type (DCD or DBD).13–16

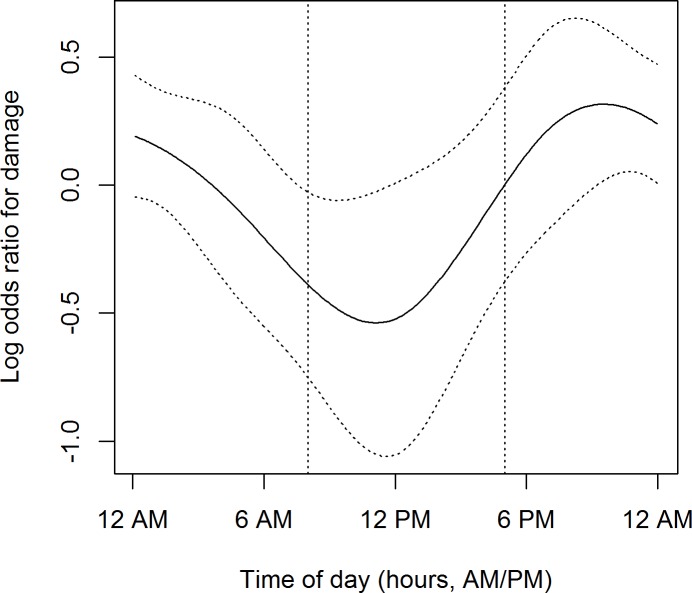

The relationship between injury and starting time of the procedure was visualised as a log OR on a continuous 24 hours’ scale by using splines regression. To correct for a possible correlation of injury within donor procedures, sandwich estimators of the SEs were used. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant and analyses were performed with SPSS V.22.0 and R V.2.3.3.

Results

During the study period, 771 organs were accepted for transplantation, of which 17 (5 livers, 8 pancreata and 4 kidneys) were declined during procurement and subsequently not transported. For all 754 accepted and transported organs, 591 forms were completed (591/754, 78%) on 133 livers (23%), 38 pancreata (6%) and 420 kidneys (71%). Response rates per organ were respectively 87%, 90% and 75%. There were 148 (148/591, 25%) organs with reported injuries; 36 livers (36/133, 27%), 10 pancreata (10/38, 26%) and 102 kidneys (102/420, 24%). Of all injured organs, 12 (2%) were discarded because of this surgical injury; 1/133 (0.8%) liver, 5/38 (13%) pancreata and 6/420 (1.4%) kidneys (p<0.001).

Daytime and night-time operating hours

With the exception of donor height (p=0.003), organs were comparable in demographical characteristics in the daytime and evening/night-time groups in univariate analysis as shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics of the study population (n=591) (only height is different between the two groups (p=0.003))

| Daytime (8:00–17:00), n=129 | Evening and night-time (17:00–8:00), n=462 | P values | |||||

| Mean (SD) | Median | Range | Mean (SD) | Median | Range | ||

| Age | 51.8 (15.3) | 55 | 14–76 | 52.2 (15.6) | 55 | 10–78 | 0.772 |

| Height | 177.4 (7.1) | 180 | 161–198 | 174.8 (9.4) | 175 | 140–200 | 0.003 |

| Weight | 76.6 (13.4) | 78 | 52–120 | 76.6 (15.1) | 77 | 35–150 | 0.996 |

| BMI | 24.3 (3.6) | 24.0 | 17.6–34.7 | 25.0 (4.1) | 24.7 | 12.5–46.3 | 0.080 |

| n (%) | n (%) | ||||||

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 75 (58) | 256 (55) | |||||

| Female | 54 (42) | 206 (45) | 0.581 | ||||

| Donor type | |||||||

| DBD | 69 (53) | 210 (45) | |||||

| DCD | 60 (47) | 252 (55) | 0.106 | ||||

| Aberrant anatomy | 32 (17) | 129 (28) | 0.458 | ||||

BMI, Body Mass Index; DBD, determination of brain death; DCD, determination of death.

n represents the number of procured organs.

P-values <0.05 are in bold.

Volume-related regional effects that may also impact the risk of surgical injury13 were not significantly different between both groups (data not shown). During daytime, 129 of 591 organs (22%) were procured and 462 organs (78%) were procured during evening/night-time. There were fewer organ injuries during daytime procurements compared with evening/night-time, respectively; 22 organs (17%) and 126 organs (27%) (p=0.016). In the full adjusted model, evening/night-time procedures remained an independent factor associated with injury (p=0.029). Of all critically injured organs, 7 out of 12 (60%) were procured in evening/night-time as compared with 5 out of 12 organs in daytime. The distribution of critical injuries (online supplementary table S1) seems therefore to correspond with the distribution of procurements (online supplementary figure S1).

bmjopen-2018-022182supp001.pdf (24.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-022182supp002.pdf (16.4KB, pdf)

Circadian points

Figure 1 shows the increased risk of injury for procedures that start in evening/night-time. The highest risk of organ injury was for procedures starting around 21:00, the lowest risk for procedures starting around 12:00 (noon).

Figure 1.

Relationship between starting time of the cold perfusion of the aorta and risk of injury.

Discussion

This study shows a relationship between surgical performance and the starting time of the procurement procedure. A higher incidence of surgical injury is observed during evening/night-time procedures as compared with daytime procedures. This association persists when adjusted for important confounders.

The relation between surgical performance and timing of surgical procedures is often highly confounded. Patients have more complicated and/or acute problems during the night.17 Also, access to imaging and laboratory testing as well as specialised operating room (OR) nurses and anaesthesiologists might be less available during night-time.13 The study population of this study, abdominal organs from deceased donors, eliminates several of these confounders. Most procedures can generally be scheduled within 6–24 hours regardless of the cause of brain death because these patients are usually haemodynamically stable. A higher number of procurement procedures during evening/night-time therefore seem to reflect issues with OR availability during the day rather than an abundance of emergency procedures. Second, abdominal organ procurement is well organised in The Netherlands; each subregion has a 24/7 availability of a self-supporting, certified organ procurement team. Such a team includes, both during daytime and evening/night-time procedures, two dedicated nurses, a dedicated anaesthesiologist and two surgeons, of whom at least one is certified for procurement procedures according to the national guidelines. This includes the European Society for Organ Transplantation procurement e-course, a minimum of 10 multiorgan procurement procedures followed by an examination by a non-regional procurement surgeon. The certified surgeons are then members of the regional dedicated procurement teams that operate on a 24-hour basis and are not involved in other clinical activities while on duty. The extensive training to become certified and the absence of other clinical activities when on call ensure a high quality of organ procurement and eliminates a major variance in operating staff. In addition, differences in hospital facilities (local vs academical) should be minimal because the teams are self-reliant and bring own standard supplies for the procedure. In our opinion, this offers a unique setting.

Another strength of this study is the very small difference in baseline characteristics of the daytime and evening/night-time groups. Donor characteristics described to be associated with procurement-related injury in kidney,14 liver16 and pancreas15 procurement procedures (such as donor age, DCD donor type, BMI, aberrant anatomy and male gender) were not significantly different. Only donor height was different between both groups, and so far this factor has not been described to influence the risk of organ injury. The similarity between both groups is likely associated with the planning of procedures, independent of donor characteristics and solely dependent of OR availability. Other relevant variables can therefore be assumed to be equal in both groups since they do not affect or are not affected by the starting time of procedures. This includes non-measured donor-associated characteristics, for example previous abdominal surgery, as well as potential differences in reporting injuries when organs were procured by surgeons from the same transplant unit as the transplanting team. Factors that might have been different and might have influenced our results include volume-related regional effects as previously described.13 The ratio between regions for daytime and evening/night-time procedures was however not different (data not shown).

In this study, we evaluated all surgical injury in a strict dichotomous way (yes/no) to analyse surgical performance in a broad sense and to avoid a loss of detailed information. In further studies, it could be of relevance to further specify the definition, type and impact of injury. In the current data for example, the number of critical injuries—leading to discarding of the organ (n=12)—is insufficient for an adequate comparison in daytime and evening/night-time groups.

A limitation of this study is the response rate for complete sets of forms of 80%; a higher response rate might have led to a higher reported number of (critical) injuries. Although the response rate could have been better, it is to be noted that the current response rate concerns organs on which two forms are digitally filled out by two independent surgeons. This two-way registration can be considered to be precise and objective.

Our results are in accordance with (non-surgical) medical studies that report a negative relation between evening/night-time or fatigue-related factors and performance, a higher rate of self-injuries among residents3 and a decreased proficiency in surgical simulations after night shifts.8 These results are conflicting with large surgical database studies that show no difference in conversion rates during cholecystectomy or outcome in patients like the occurrence of serious adverse events.6 18 Rothschild et al, on the other hand, found an increased rate of complications during post night-time surgical procedures performed by physicians with sleep opportunities of less than 6 hours.10 A study on liver transplantation found that surgical procedures during night-time took longer and were associated with a higher risk of early death, although without any effect on perioperative complications or long-term survival.19 Also in kidney transplantation, more perioperative complications20 but less technical graft failure21 were seen in night-time procedures. The latter did not take into account a difference in surgical experience between daytime and night-time procedures; night-time procedures are rather performed by consulting surgeons as compared with daytime procedures that are usually performed by (supervised) surgical residents. In the current study, however, all procedures were performed by the same group of dedicated surgeons and teams.

These studies seem to report contradictory findings between short-term or non-patient outcomes on the one hand and long-term outcome in patients. This observation is reflected in our data; we noticed a higher incidence of surgical injuries during night-time (this study) but no difference in 1-year graft survival between injured and intact organs in a previous analysis of the same cohort.13 This indicates that the pathway leading to a negative outcome in surgical patients is complex and multifactorial, and only the most severe surgical injuries might result in clinically measurable negative outcome. To find a significant difference in outcome in patients that can be related to the timing of procedures or ‘fitness’ of surgeons, higher numbers are probably needed. This study can therefore only assess (technical) surgical performance.

The increased injury rates during evening/night-time operating hours may indicate that surgical performance is affected by time of day. The aetiology of this association is however not yet clear. The negative effect of evening/night-time procedures suggests an effect of fatigue-related factors. Fatigue was however not measured in this study and should theoretically play a smaller role because procurement teams can rest between procedures and do not participate in other clinical activities when on call. Other mechanisms might however contribute; the surgical injury pattern in this study shows, for example, a remarkable resemblance with circadian rhythm and associated biological hormone levels as observed in chronobiology.22 To further identify the mechanism behind the higher injury rate during evening/night-time, it will be essential to objectively measure the surgeon’s fitness before and after procurement. Current research on the validation and clinical application of such a ‘Fit to Perform’ test is ongoing.23 It might give an objective tool to evaluate the relation between the fitness of a surgeon and his surgical performance.

We believe this study shows that evening/night-time procedures might present a suboptimal setting for organ procurement. Although the causal pathway is not yet clear, our results do suggest that time of day should be taken into account to optimise the quality of organ procurement. Theoretically, transplantations in the evening/night-time may also be related to a higher risk of complications. If so, this poses a dilemma because the timing of the procurement also affects the timing of the transplantation. Although a higher risk of complications in transplantations during the evening/night-time has not been described, it seems best to perform the procurement early in the morning. In such a way, it is still possible to subsequently start the transplantation operation that same afternoon. Timing may even be of relevance for other surgical procedures. This would mean that, in the absence of acute pathology, surgeries should be preferably performed during daytime.

Conclusion

This study shows an increased incidence of surgical injury in organ procurement procedures during evening/night-time, as compared with daytime. Time of day might (in)directly influence surgical performance and should be considered a potential risk factor for injury in organ procurements.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge Cynthia Konijn, Dilesh Kishoendajal and Steffen de Groot (Dutch Organ Transplant Registry) for their efforts in collecting the data.

Footnotes

Contributors: JdB, KvdB and DB hypothesised that a relationship may be present between time of day and the incidence of surgical injury. KvdB is involved in the Fit to Perform trial currently performed in The Netherlands. Data on procured organs are provided by all six transplanting centres in the Netherlands to the Dutch Transplant Foundation. Permission to use these was granted by delegates from all centres: RP (Groningen), JdJ (Rotterdam), KD (Maastricht), MN (Leiden) and DvdV (Nijmegen). Data were then obtained via the Dutch Transplant Foundation where KO-dV and BH-K were involved. Data were analysed and statistical analysis was performed and interpreted by JdB, KvdB, DB and HP of the Statistical Department. The manuscript was then drafted by JdB, KvdB, DB and HP. The draft manuscript was critically revised by all involved.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data are available on request at the Dutch Transplant Foundation. Permission for this analysis was granted by the national competent authority, the Dutch Transplant Foundation, on 6 April 2017.

References

- 1.Landrigan CP, Rothschild JM, Cronin JW, et al. Effect of reducing interns' work hours on serious medical errors in intensive care units. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1838–48. 10.1056/NEJMoa041406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodriguez-Jareño MC, Demou E, Vargas-Prada S, et al. European working time directive and doctors' health: a systematic review of the available epidemiological evidence. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004916 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-004916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ayas NT, Barger LK, Cade BE, et al. Extended work duration and the risk of self-reported percutaneous injuries in interns. JAMA 2006;296:1055–62. 10.1001/jama.296.9.1055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnedt JT, Owens J, Crouch M, et al. Neurobehavioral performance of residents after heavy night call vs after alcohol ingestion. JAMA 2005;294:1025–33. 10.1001/jama.294.9.1025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Griffith C, Mahadevan S. Sleep-deprivation effect on human performance: a meta-analysis approach. J Sleep Res Sleep Med 2006;19:318–26. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vinden C, Nash DM, Rangrej J, et al. Complications of daytime elective laparoscopic cholecystectomies performed by surgeons who operated the night before. JAMA 2013;310:1837–41. 10.1001/jama.2013.280372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grantcharov TP, Bardram L, Funch-Jensen P, et al. Laparoscopic performance after one night on call in a surgical department: prospective study. BMJ 2001;323:1222–3. 10.1136/bmj.323.7323.1222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brandenberger J, Kahol K, Feinstein AJ, et al. Effects of duty hours and time of day on surgery resident proficiency. Am J Surg 2010;200:814–9. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wiesner R, Edwards E, Freeman R, et al. Model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) and allocation of donor livers. Gastroenterology 2003;124:91–6. 10.1053/gast.2003.50016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rothschild JM, Keohane CA, Rogers S, et al. Risks of complications by attending physicians after performing nighttime procedures. JAMA 2009;302:1565–72. 10.1001/jama.2009.1423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Connor J, Norton R, Ameratunga S, et al. Driver sleepiness and risk of serious injury to car occupants: population based case control study. BMJ 2002;324:1125 10.1136/bmj.324.7346.1125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horne JA, Reyner LA. Sleep related vehicle accidents. BMJ 1995;310:565–7. 10.1136/bmj.310.6979.565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Boer JD, Kopp WH, Ooms K, et al. Abdominal organ procurement in the Netherlands—an analysis of quality and clinical impact. Transpl Int 2017;30:288–94. 10.1111/tri.12906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ausania F, White SA, Pocock P, et al. Kidney damage during organ recovery in donation after circulatory death donors: data from UK national transplant database. Am J Transplant 2012;12:932–6. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03882.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ausania F, Drage M, Manas D, et al. A registry analysis of damage to the deceased donor pancreas during procurement. Am J Transplant 2015;15:2955–62. 10.1111/ajt.13419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ausania F, White SA, Coates R, et al. Liver damage during organ donor procurement in donation after circulatory death compared with donation after brain death. Br J Surg 2013;100:381–6. 10.1002/bjs.9009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anselmi L, Meacock R, Kristensen SR, et al. Arrival by ambulance explains variation in mortality by time of admission: retrospective study of admissions to hospital following emergency department attendance in England. BMJ Qual Saf 2017;26:613–21. 10.1136/bmjqs-2016-005680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Govindarajan A, Urbach DR, Kumar M, et al. Outcomes of daytime procedures performed by attending surgeons after night work. N Engl J Med 2015;373:845–53. 10.1056/NEJMsa1415994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lonze BE, Parsikia A, Feyssa EL, et al. Operative start times and complications after liver transplantation. Am J Transplant 2010;10:1842–9. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03177.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fechner G, Pezold C, Hauser S, et al. Kidney’s nightshift, kidney’s nightmare? Comparison of daylight and nighttime kidney transplantation: impact on complications and graft survival. Transplant Proc 2008;40:1341–4. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.02.072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brunschot DM, Hoitsma AJ, van der Jagt MF, et al. Nighttime kidney transplantation is associated with less pure technical graft failure. World J Urol 2016;34:955–61. 10.1007/s00345-015-1679-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jasper I, Roenneberg T, Häussler A, et al. Circadian rhythm in force tracking and in dual task costs. Chronobiol Int 2010;27:653–73. 10.3109/07420521003663793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huizinga CRH, de Kam ML, Stockmann H, et al. Evaluating fitness to perform in surgical residents after night shifts and alcohol intoxication: the development of a "fit-to-perform" test. J Surg Educ 2018;75:968–77. 10.1016/j.jsurg.2018.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-022182supp001.pdf (24.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-022182supp002.pdf (16.4KB, pdf)