Abstract

Objective

Paediatric heart transplantation (PHTX) comprises 12% of all cardiac transplants and many of the children now survive into adulthood. Only a few studies have investigated the long-term psychosocial well-being of young adult patients after PHTX; no studies have investigated developmental tasks of emerging adulthood in different domains (family, social environment, education and profession, partnership, social environment).

Setting

Specialised heart centre in Germany.

Participants

Thirty-eight young adults aged 22.11 years (SD=4.7) who underwent PHTX and a control group of 46 participants with no known chronic diseases, aged 22.91 years (SD=1.8), participated in the study.

Outcome measures

All participants completed the following questionnaires: sociodemographic, the F-SozU, to measure perceived social support, the Gießener Beschwerde-Bogen to measure subjective complaints experienced by patients, the KIDSCREEN-27 to measure well-being and the SF-36 to measure health-related quality of life (QoL).

Results

‘Family’: the quality of the relationship with the parents was found to be equal in both groups, while PHTX patients stayed in closer spatial proximity to their parents. ‘Social environment’: PHTX patients reported lower social support by peers than the control group. ‘Education and profession’: PHTX patients most often worked full-time (23%), had no job and/or received a pension (21%). In comparison, most of the healthy controls did an apprenticeship (40%) and/or worked part time (32%). ‘Partnership’: fewer of the PHTX patients had a partner than the control group while relationship duration did not differ. In exploratory regression analyses, social support by peers predicted physical QoL, whereas physical complaints and the physical role predicted mental QoL in PHTX patients.

Conclusions

Our exploratory findings highlight important similarities and differences in specific developmental tasks between PHTX patients and healthy controls. Future studies should focus on developmental tasks of PHTX patients in this age group more systematically, investigating their role in physical and mental well-being in a confirmatory manner.

Keywords: heart transplantation, developmental tasks, paediatric cardiology, quality of life, psychosocial

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To our knowledge, this study is one of the first to investigate the developmental tasks in the specific group of emerging adults after paediatric heart transplantation to have theoretical implications and which is relevant to the psychosocial care of these patients.

This is a hypothesis-generating study with the unique approach of using well-established questionnaires for the exploration of developmental domains.

This study is cross-sectional, so no inferences can be made with regard to development over time.

A convenience sample control group was used, which limits generalisability of the results.

As this was an exploratory study, results should be replicated in confirmatory manner, based on carefully developed hypotheses.

Introduction

Paediatric heart transplantation (PHTX) is an established therapy for end-stage cardiac disease1 and has increased worldwide to more than 12 000 reported transplants in children since the first procedure in 1967.2 In 2014, a total of 586 heart transplants in children (aged <18 years) were performed worldwide.3 They comprise 12% of all cardiac transplants reported to the Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation.4 Median survival of children after heart transplantation has increased to about 20 years,5 6 with the lowest 3 year survival rate in children in Europe under the age of 1 (84.0) and the highest in children between the ages 6 and 10 (89.1).7 8 Accordingly, an increasing amount of research focuses on long-term outcomes and quality of life (QoL) after PHTX. Although it is life-saving, it is not curative and children are confronted with chronic health problems.9 Research generally suggests that chronic and/or serious disease in childhood is associated with an increased risk for non-normative physical, psychological and social development.10–12 Serious disease is negatively associated with QoL and identity development of children and adolescents and puts young adults at risk for reduced occupational and social success.13–16 When it comes to PHTX, research shows that it is associated with large improvements in functional status.17 At the same time, a substantial proportion of children and adolescents after PHTX report psychological problems, such as depression, anxiety and behavioural problems.18–22 These psychological problems potentially negatively impact QoL, alongside sociodemographic and medical factors such as renal diseases23 and infections.24 Later in life, the majority of patients achieve important academic and professional milestones and social well-being.25 A study on adult patients after PHTX reports good QoL and good academic and professional achievement, while patients were most satisfied in the family domain and least satisfied in the psychological and spiritual domain. Most respondents had graduated from high school, reported an average annual income and lived independently.26 Another study focused on the population of young adults (aged 18–25) comparing PHTX patients with two other patient groups (patients with congenital heart disease of moderate severity and patients with congenital heart disease of complex severity). Results showed no differences between the groups in terms of psychosocial maturity, parental fostering of autonomy and transition readiness. Higher psychosocial maturity and parental fostering of autonomy were associated with better perceived mental health and QoL.27 While this study has contributed important insights into psychosocial development of young adults after PHTX, more research into the unique developmental tasks of PHTX patients during emerging adulthood are needed in order to discern a multitude of factors that are potentially relevant to their subjective well-being and QoL.

Emerging adulthood describes a developmental phase of individuals in industrialised countries lasting from the late teens to late 20s, with specific developmental tasks: (1) detachment from the family with spatial (home stay), financial (support from parents) and emotional independence (autonomy experience); (2) apprenticeship, training and entering career with the topics of leaving school and finding a job (professional identity) and (3) entering romantic relationships (partner selection, building an intimate relationship with a partner).28–31 In addition, the social environment, especially the peer group, is crucial for well-being and closely linked to the self-reported QoL in this age group.32 In the present study, these developmental tasks in young adults after PHTX were investigated by using well-established questionnaires and by regrouping subscales and items into developmental domains for exploratory analysis listed in table 1. Furthermore, we looked at subjective physical well-being (specifically, the concept subjective physical complaints comprising the subscales fatigue tendency, gastric complaints, limb pain and heart complaints as well as the concept physical well-being) and at psychological well-being. Finally, we assessed physical QoL (by means of the SF-36 subscales physical functioning, general health, vitality, physical role, pain and the physical summary scale) and psychological QoL (by means of the SF-36 subscales vitality, social functioning, emotional role, mental health and the mental summary scale), in order to gain an impression of the current subjective health status of the sample.

Table 1.

Overview of the instruments we used, clarifying domains and concepts

| Domain | Concept | Instrument | (Sub)scale/item |

| Family | |||

| Current living situation | Demographic questionnaire | Living Situation (Item) | |

| Spatial independence | Demographic questionnaire | Distance from Parents (Item) | |

| Relationship with the parents | Kidscreen-27 | Autonomy & Parent Relation Subscale | |

| Education and profession | |||

| Educational level | Demographic questionnaire | Highest Completed Education (Item) | |

| Repeated school years | Demographic questionnaire | Number of Repeated School Years (Item) | |

| Employment situation | Demographic questionnaire | Current Employment Situation (Item) | |

| Financial situation | Demographic questionnaire | Maintaining Livelihood (Item) | |

| Partnership | |||

| Marital status | Demographic questionnaire | Marital Status (Item) | |

| Partner status | Demographic questionnaire | Partner Status (Item) | |

| Duration of longest relationship | Demographic questionnaire | Duration of Longest Relationship (Item) | |

| Social environment | |||

| Social support in general | F-SozU | F-SozU Total Score | |

| Social support by peers | Kidscreen-27 | Subscale Perceived Social Support & peers | |

| Feelings about school | Kidscreen-27 | Subscale School | |

| Social functioning | SF-36 | Subscale Self-Rated Social Function | |

| Reintegration after PHTX | Demographic questionnaire | Reintegration at School (item) | |

| Subjective physical well-being | |||

| Subjective physical complaints | GBB | Total Score | |

| Fatigue Tendency | GBB | Subscale Fatigue Tendency | |

| Gastric Complaints | GBB | Subscale Gastric Complaints | |

| Limb Pain | GBB | Subscale Limb Pain | |

| Heart Complaints | GBB | Subscale Heart Complaints | |

| Physical well-being | Kidscreen-27 | Subscale Physical Well-Being | |

| Subjective psychological well-being | |||

| Psychological well-being | Kidscreen-27 | Subscale Psychological Well-Being | |

| QOL | |||

| Physical functioning | SF-36 | Subscale Physical Functioning | |

| General health | SF-36 | Subscale General Health | |

| Physical limits in everyday functioning | SF-36 | Subscale Physical Role | |

| Pain | SF-36 | Subscale Bodily Pain | |

| Physical quality of life | SF-36 | Physical Summary Scale | |

| Vitality | SF-36 | Subscale Vitality | |

| Social functioning | SF-36 | Subscale Social Functioning | |

| Emotional limits in everyday functioning | SF-36 | Subscale Emotional Role | |

| Mental health | SF-36 | Subscale Mental Health | |

| Psychological quality of life | SF-36 | Mental Summary Scale | |

GBB, Gießener Beschwerde-Bogen; SF-36, Short-Form-36.

Methods

Participants

Group of PHTX patients

A total of 169 children and adolescents underwent a PHTX at our hospital from 1986 to 2010, of which 101 survived. In this cross-sectional study, young adults between the ages of 16 and 35 years who underwent heart transplantation when they were children (<18 years) at a specialised heart centre were eligible for participation. Patients were recruited during the routine medical checks in the hospital. Participation was voluntary. Fifty-two eligible patients met the inclusion criteria, of whom 38 agreed to participate in the study.

If interested in participation, they received an information letter from the research team about the objectives, design and procedure of the study. Informed consent was obtained from all participants via mail. After that, participants received questionnaires on paper, a stamped envelope and a letter with instructions on how to fill out and return the questionnaires via mail. Patients were instructed to fill out the questionnaires at home and to return the completed questionnaires using the stamped envelope.

Inclusion criteria for PHTX patients:

PHTX at our hospital from 1986 to 2010.

Current age between 16 and 35 years.

Group of healthy controls

A comparison group of 46 young healthy controls between the ages of 19 and 26 years with no known chronic diseases was recruited via social networks and personal contacts. We ensured that the control group had the same mean age and gender distribution as the PHTX group. Eligible participants were recruited via social network and personal contacts and, if interested in participation, were contacted by phone, email or personally. Informed consent of each participant was obtained; participants then received the questionnaires via email, mail (together with a stamped envelope) or in person. Questionnaires were returned via mail or in person.

Outcomes had been determined for all patients who previously asked for results by the end of the data collection (December 2016). Due to the exploratory design, the development of the research question was not informed by patients’ priorities, experience and preferences.

Inclusion criteria for healthy controls:

Young adults between the ages of 16 and 35 years.

No known chronic disease.

Patients and public involvement

The study was designed to understand patients’ experience and to observe developmental tasks of young adults after PHTX. However, patients were not included in the design of the survey, recruitment or conduct of the study. Patients were informed about the option to be debriefed about the study results after completion of the study.

Instruments

Demographics

Demographic information was obtained via a questionnaire developed by the research team with the following items: marital status, partner status, duration of longest relationship, living situation, distance from parents’ home, educational level, number of repeated school years, current employment situation, maintaining livelihood, successful reintegration at school after PHTX. For an overview of items used for the analysis of each developmental domain, see table 1. Additionally, the variables age, sex and date of transplantation were obtained from medical records.

Social Support Questionnaire-Short Form

The German version of the Social Support Questionnaire-Short Form (Fragebogen zur Sozialen Unterstützung; F-SozU, K-14) was used, which is a 14-item self-report of subjectively perceived or anticipated social support. A total score can be computed, which ranges from 1 to 5 and which was used for the analysis of the domain ‘social environment’; see table 1. Psychometric properties are good.33

Giessen Complaints Inventory

The German version of the Giessen Complaints Inventory (Gießener Beschwerde-Bogen, GBB) by Brähler and Scheer (1995) was used. The GBB is an instrument for physical complaints frequently used in Germany which measures subjective limitations experienced by patients due to their physical symptoms. The questionnaire comprises 24 items and contains the following subscales: fatigue tendency, gastric complaints, limb pain and heart complaints. Scores per subscale range from 0 to 24. A total score (general discomfort) can be computed, which ranges from 0 to 96 points. The total score was used for the analysis of the domain ‘subjective physical well-being’. Psychometric properties are good.

KIDSCREEN-27

The KIDSCREEN-27 by Ravens-Sieberer et al34 is a German questionnaire for health-related QoL specifically developed for children. It measures the following five subscales: ‘autonomy and parent relations’, which we used in the domain ‘family’, ‘perceived social support & peers’ and ‘school’, both of which we used in the domain ‘social environment’; ‘physical well-being’ and ‘psychological well-being’, which we used in the domains ‘subjective physical well-being’ and ‘subjective psychological well-being’ (see table 1). Scores per subscale range from 0 to 100, with a higher score indicating a better QoL. A total score can be computed ranging from 0 to 100 points. Psychometric properties are good.34

Short-Form-36-Item Health Survey

The German Version of the Short-Form-36 (SF-36) by Bullinger and Kirchberger35 was used, which is a generic health survey comprising 36 items in eight subscales (physical functioning, role functioning physical, bodily pain, general health perceptions, vitality, social functioning, role functioning emotional and mental health). We subsumed each of the subscales into the domains ‘subjective physical well-being’ and ‘subjective psychological well-being’, as appropriate (see table 1). The subscales can be aggregated into two component summary scores representing the physical summary scale and the mental summary scale, both of which we used in the domain ‘quality of life’ (see table 1). Subscale and summary scores range from 0 to 100, based on transformed z-scores with multiplication of the regression coefficients of the normative sample. A higher score indicates a better QoL. Psychometric properties are good.35

Analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics 23 was used for descriptive and inferential statistics. A p≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. χ² tests for dichotomous variables univariate analyses of variance were performed for exploratory group comparisons in all developmental domains (for an overview of developmental domains, see table 1). Univariate regressions were conducted for exploratory analyses of predictors of physical and psychological QoL.

Results

Sample characteristics

All 38 participants of the PHTX group underwent heart transplantation when they were children, with a mean age at time of transplantation of 10.95 years (SD=3.7). The mean age at time of recruitment was 22.11 years (SD=4.7), ranging from 16 to 35 years. Fifty per cent of the patients were male. The mean waiting time for an organ was 0.47 years (SD=0.5). Number of years between PHTX and assessment was on average 11.16 years (SD=5.3), ranging from 4 to 23 years.

In the control group, mean age at assessment was 22.91 years (SD=1.8), ranging from 19 to 26 years; 45% were male.

Between groups, there are no significant differences in age (F(1,45.67)=1.00, p=0.285) or gender (χ2 (1, n=84)=1.98, p=0.159). Regarding the educational level, the control group was significantly more highly educated than the PHTX patients (F(1,79)=130.39, p<0.001, high school or university in 96% and 8%, respectively). Furthermore, the control group individuals reported being in a partnership more often than the PHTX patients (χ2 (1, n=84)=9.42, p=0.002, 65% and 32%, respectively).

Family

In this domain, we focused on the current living situation, spatial independence and relationship with the parents, with the following results: The living situation differs significantly between the PHTX and control group, F(1,82)=4.10, p=0.046. Twenty-one of the PHTX patients (55%) lived with their parents, while the remaining 45% had moved out. Of those 45%, 18% lived with their partner, 11% lived alone, 11% lived next to their parents in a separate apartment and 5% shared a flat. By contrast, only 22% of the control group lived with their parents, while 78% had moved out, see table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics and metrics of family variables in the PHTX group and control group

| Characteristic | Assessed by | Value | PHTX (n=38) | Control group (n=46) | P values |

| Living situation | Social demographic questionnaire | With parents | 21 (55%) | 10 (22%) | 0.046 |

| With partner | 7 (18%) | 9 (20%) | |||

| Alone | 4 (11%) | 10 (21%) | |||

| Next to parents | 4 (11%) | 0 | |||

| Flat share | 2 (5%) | 17 (37%) | |||

| Distance to parents’ home in km | Social demographic questionnaire | Mean | 1.66 | 213.37 | <0.001 |

| SD | 1.26 | 280.99 | |||

| Relation to parents and autonomy | KIDSCREEN-27 | Mean | 59.15 | 53.49 | 0.020 |

| SD | 9.27 | 7.78 |

PHTX, paediatric heart transplantation.

In the subgroup of participants who no longer live with their parents, the distance to the parents’ home in km differs significantly between the groups (F(1,26.0)=45.57, p<0.001). The PHTX stay closer to their parents’ house (M=1.66 km, SD=1.26 km), while the healthy controls move further away (M=213.37 km, SD=280.99 km).

The perceived quality of the relationship with their parents and self-estimated autonomy are reported differently in the two groups (F(1,57)=5.72, p=0.02), with higher scores reported by the PHTX group than by the control group, indicating higher perceived quality of the relationship and perceived autonomy in the PHTX group, see table 2.

Education and profession

In this domain, we focused on the number of repeated school years, the educational level, employment situation and financial situation. The educational level differs significantly between the two groups (F(1,79)=130.4, p<0.001): the PHTX patients less often completed high school education than healthy controls (52% and 96%, respectively), fewer of them were currently studying (3% and 62%, respectively) and a smaller percentage achieved an academic degree (5% and 33%, respectively). Three PHTX patients (8%) had dropped out of school, as opposed to no participants from the healthy control group. At school, the PHTX group had to repeat a grade significantly more often than the control group (χ2 (1, n=80)=20.53, p<0.001). Ten PHTX patients (26%) repeated one school year and three PHTX patients (8%) repeated two school years, while none of the control group repeated a school year.

The type of the current job also differs between the two groups (χ2 (1, n=79)=26.36, p<0.001), with PHTX patients having part-time jobs less often than the control group (9% and 34%, respectively). The PHTX group’s occupations are distributed between jobs in full time (23%), training (11%), apprenticeship (17%), unemployed (23%), retired (11%), half time jobs (3%) or part time jobs (6%) and other (6%). The control group reported the following occupations: full time (5%), training (2%), apprenticeship (40%), unemployed (5%), half time jobs (2%), part time jobs (32%) and other (14%). Finally, sources of financial support differ between the groups (F(1,78)=13.44, p<0.001): sources of income are more widely distributed in PHTX patients, in comparison with the control group (see table 3). Thirty-four per cent of the PHTX group reported being financially independent because of a paid job, as opposed to 64% of the control group. Furthermore, PHTX patients less often receive financial support from their parents than the control group (χ2 (1, n=80)=11.75, p=0.001).

Table 3.

Characteristics and metrics of school, apprenticeship and financial variables in PHTX and control group

| Characteristics | Value | PHTX (n=38) | Control group (n=46) | P values |

| Repeated years at school | Yes | 14 (37%) | 0 | <0.001 |

| No | 21 (55%) | 46 | ||

| Number of repeated years at school | 0 | 20 (53%) | 46 | <0.001 |

| 1 | 10 (26%) | 0 | ||

| 2 | 3 (8%) | 0 | ||

| Education level | Still attending school | 4 (10%) | 0 | <0.001 |

| No examination | 3 (8%) | 0 | ||

| School for children with learning difficulties | 5 (13%) | 0 | ||

| Secondary school level | 22 (58%) | 1 (2%) | ||

| A-level | 1 (3%) | 27 (59%) | ||

| College | 1 (3%) | 0 | ||

| University | 1 (3%) | 15 (33%) | ||

| Current job | Full time | 8 (21%) | 2 (4%) | <0.001 |

| Half time | 1 (3%) | 1 (2%) | ||

| Part time | 2 (5%) | 14 (30%) | ||

| Training | 4 (11%) | 1 (2%) | ||

| Apprenticeship | 6 (16%) | 18 (39%) | ||

| Unemployed | 8 (21%) | 2 (4%) | ||

| Retired | 4 (11%) | 0 | ||

| Other | 2 (5%) | 6 (13%) | ||

| Financial life (multiple choice) | Own money via job | 13 (34%) | 30 (65%) | <0.001 |

| Parents/family members | 15 (39%) | 37 (80%) | ||

| Dole | 5 (13%) | 0 | ||

| Pension | 8 (21%) | 0 | ||

| Welfare | 4 (11%) | 0 | ||

| Others | 4 (11%) | 8 (17%) |

PHTX, paediatric heart transplantation.

Partnership

In this domain, we focused on marital status, partner status and the duration of the longest relationship. The marital status differs significantly between the two groups (χ2 (1, n=84)=14.34, p=0.002): 92% of the PHTX patients reported being single, 5% were married and 3% divorced. In comparison, 100% of the control group were single and none were married or divorced. In the subgroup of single participants, 65% of the PHTX patients and 32% of the control group reported having a partner (χ2 (1, n=84)=9.42, p=0.002). The duration of the longest relationship does not differ between groups (F(1,75)=1.52, p=0.222); see table 4 for an overview.

Table 4.

Characteristics and metrics of partnership in PHTX and control group

| Characteristics | PHTX (n=38) |

Control group (n=46) |

P values |

| Marital status | 0.002 | ||

| Single | 35 (92%) | 46 (100%) | |

| Divorced | 1 (3%) | 0 | |

| Married | 2 (5%) | 0 | |

| Having a partner | 0.002 | ||

| Yes | 12 (32%) | 30 (65%) | |

| No | 26 (68%) | 16 (35%) | |

| Duration of longest relationship (in months) | 0.222 | ||

| Mean | 23.45 | 31.67 | |

| SD | 25.81 | 29.36 |

PHTX, paediatric heart transplantation.

Social environment

In this domain, we focused on social support in general, social support by peers, feelings about school, reintegration after PHTX as well as the self-rated social function, with the following results. The PHTX group was asked if reintegration at school after HTX was ‘successful or not’ (dichotomous variable) as part of the demographic questionnaire. Fifty-eight per cent reported the re-entry into school as not successful. The total score of the F-SozU differs between the groups (F(1,44.92)=23.39, p<0.001), with the control group reporting higher perceived social support than the PHTX group. On the KIDSCREEN-27 subscale ‘social support by peers’, the PHTX group scored lower than the control group (F(1,75)=1.52, p=0.22), indicating less perceived support by their peer group. On the SF-36 subscale ‘social functioning’, the PHTX group also scored lower than healthy controls (F(1,82)=6.11, p=0.015), indicating poorer social functioning, see table 5.

Table 5.

Social support of PHTX patients and control group

| Characteristics | Assessed by | Value | PHTX (n=46) | control group (n=38) | P values |

| Integration in school | Social demographic questionnaire | Successful | 16 (42%) | ||

| Not successful | 22 (58%) | ||||

| Social support | F-SozU | Mean | 4.31 | 4.77 | <0.001 |

| SD | 0.65 | 0.28 | |||

| Social support by peers | KIDSCREEN-27 | Mean | 45.5 | 50.38 | 0.046 |

| SD | 10.98 | 7.39 | |||

| Feelings about school | KIDSCREEN-27 | Mean | 50.90 | 51.19 | 0.901 |

| SD | 9.47 | 6.37 | |||

| Social functioning | SF-36 | Mean | 80.59 | 91.03 | 0.022 |

| SD | 24.26 | 13.86 |

PHTX, paediatric heart transplantation.

Subjective well-being and quality of life

In this domain, we focused on different aspects of subjective physical well-being (subjective physical complaints, physical functioning, general health, physical limits in everyday functioning, pain and physical well-being), psychological well-being (psychological well-being, vitality, social functioning and emotional limits in everyday functioning) as well as the physical and psychological QoL.

Subjective physical well-being

Subjective physical complaints, as assessed with the GBB total score, do not differ between the two groups (F(1,83)=0.78, p=0.379). On a subscale level, a significant difference was found on the subscale fatigue tendency (F(1,83)=4.39, p=0.039), with PHTX patients reporting more fatigue symptoms than the control group (M=3.0, SD=2.79 and M=1.91, SD=1.95, respectively). No differences were found on the subscales of gastric complaints, limb pain or heart complaints. On the subscale physical well-being of the Kidscreen-27, no significant difference was observed between groups (F(1,60)=3.67, p=0.06).

Subjective psychological well-being

No significant difference on the Kidscreen-27 subscale ‘psychological well-being’ was observed between groups (F(1,60)=3.93, p=0.052).

QoL

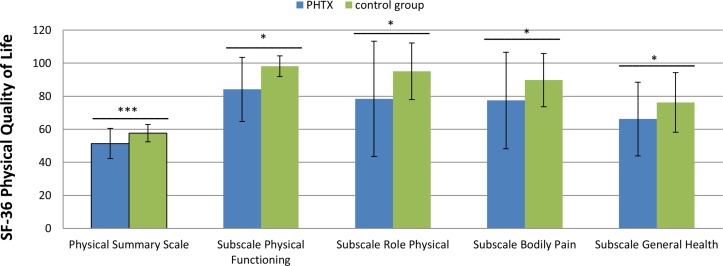

The PHTX patients reported a lower level of physical QoL based on the physical summary scale of the SF-36 than the control group (F(1,43.54)=14.51, p<0.001). Also, the PHTX patients scored lower in all physical subscales than the control group (physical functioning: F(1,82)=21.69, p<0.001; role physical: F(1,78)=7.92, p=0.006; bodily pain: F(1,82)=6.04, p=0.016; general health: F(1,78)=4.9, p=0.03) (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

Means of z-transformed scores of the SF-36 physical summary scale and all physical subscales raw values 0–100 of PHTX and control group. PHTX, paediatric heart transplantation; SF-36, Short-Form-36.

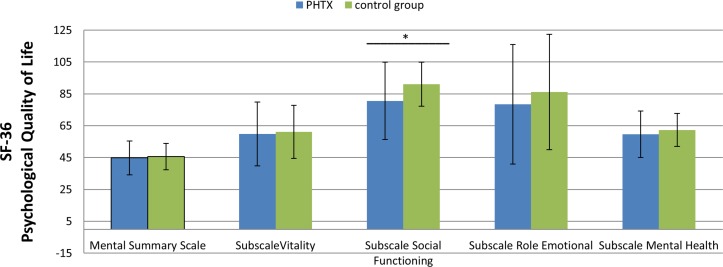

However, the PHTX patients showed no differences in psychological QoL, based on the mental summary scale of the SF-36 (F(1,76)=0.15, p=0.70). On the subscale-level, only ‘social functioning’ differed between the groups (F(1,82)=6.11, p=0.015), with a lower score reported by the PHTX patients (see figure 2).

Figure 2.

Means of z-transformed scores of the SF-36 mental summary scale and all psychological subscales raw values 0–100 of PHTX and control group. PHTX, paediatric heart transplantation; SF-36, Short-Form-36.

Predictors of physical and mental quality of life in PHTX patients

To explore which factors predict QoL (psychological and physical) in PHTX patients, we correlated all variables (from the domains family, education and profession, partnership, social environment and subjective well-being) with the physical and psychological component summary scores of the SF-36 as a first step. Based on significant exploratory correlations, variables were then selected as predictors for each of the two scales. Regression assumptions were checked and met for both regressions. Next, we calculated two stepwise univariate regression models (one for each summary scale of the SF-36). Variables were included stepwise as independent variables in the regression model. In order to avoid overfitting the model, all SF-36 subscales comprising the physical QoL component were excluded from the regression analysis, with the physical summary scale as criterion. All SF-36 subscales comprising psychological QoL were excluded from the analysis, with the mental summary scale as criterion.

Predictors of physical quality of life

The following predictors were entered in the first regression model, with physical QoL entered as criterion: (1) school reintegration (r=0.497, p=0.01); (2) physical complaints (r=−0.381, p=0.035); (3) vitality (r=0.369, p=0.041); (4) social support by peers (r=0.771, p<0.001) and (5) subjective physical and psychological well-being (r=0.595, p=0.012, respectively, r=0.520, p=0.033). The analyses revealed that better social support by peers (comprising, for instance, the items ‘have you spent time with your friends?’ or ‘have you and your friends helped each other’) predicts a higher physical QoL in PHTX patients, explaining 58.9% of variance (p=0.001). See table 6 for the full regression model.

Table 6.

Stepwise linear univariate regression model: predictors of QoL (n=38)

| Criterion | Predictor | B | SE | P values | 95% CI for B | |

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Physical QoL | Peers (KIDSCREEN-27) | 0.77 | 0.15 | 0.001 | 0.34 | 0.96 |

| Constant | 6.95 | 0.01 | 5.81 | 35.64 | ||

| Mental QoL | Physical complaints (GBB) | 0.4 | 0.09 | 0.005 | −0.45 | −0.53 |

| Role physical (physical subscale SF-36) | 0.68 | 0.07 | <0.0001 | 0.15 | 0.45 | |

| Constant | 6.5 | 0.008 | 5.53 | 32.55 | ||

GBB, Gießener Beschwerde-Bogen; PHTX, paediatric heart transplantation; QoL, quality of life.

Predictors of psychological QoL

The following predictors were entered in the second regression model, with psychological QoL as criterion: (1) duration of longest relationship (r=−0.455, p=0.022); (2) distance from parents’ home (r=−0.443, p=0.013); physical complaints (r=−0.491, p=0.005); (3) role physical (r=0.498, p=0.005) and (4) subjective psychological well-being (r=0.683, p=0.003). The analysis revealed two significant predictors: fewer physical complaints and a better role functioning predicted better psychological QoL in PHTX patients, explaining 89.0% of variance (p<0.001). See table 6 for the best fitting model.

Discussion

In this study, we explored developmental tasks of emerging adulthood in a sample of young adults after PHTX in an exploratory manner. The following categories were examined: (1) family (current living situation, spatial independence, relationship with the parents), (2) education and profession (educational level, repeated school years, employment situation, financial situation), (3) partnership (marital status, partner status and duration of longest relationship) and (4) social environment (perceived social support in general, by peers, feelings about school, social functioning and reintegration at school after PHTX). Additionally, subjective physical well-being, subjective psychological well-being and QoL (physical and psychological) were assessed. Finally, we investigated which of the variables from domains (1)–(4) as well as variables from the domains subjective physical and psychological well-being predict self-reported QoL.

In comparison to our control group, PHTX patients more often live with their parents and when they move out, they stay in closer proximity to their parents. We found no differences in the perceived quality of the relationship with the parents.

When it comes to financial independence, the PHTX patients rely less on their family for financial support than the control group. PHTX patients held full-time positions more frequently than the control group, while healthy controls more often chose part time work. Importantly, a significant percentage of PHTX patients had no job and/or received a pension. These findings are similar to those of a recent study by Grady and colleagues, who examined 88 young adults after PHTX in their early 20s.36 About 50% of the patients reported working for income, compared with 51% in our study (part time work, full time work and apprenticeship taken together). As in our study, PHTX patients more frequently had to repeat at least one school year, probably due to health problems and hospital stays, the choice of full-time work, which might reflect the choice for non-academic career paths, might be related to more academic difficulties related to their disease. Future studies should focus on this issue, systematically investigating academic disadvantages and choices due to underlying disease and the challenges that come with PHTX.

When it comes to partnership, more PHTX patients reported being single than healthy individuals from the control group, even though the groups did not differ in age. However, the duration of the longest relationship did not differ between groups. The results differ somewhat from those of the study by Grady and colleagues,36 in which only 9% of the patients reported having a partner, compared with the 32% in our study. This finding might be due to difficulties in initiating partnership, while partnership stability might not be compromised in PHTX patients once they have found a partner. Furthermore, PHTX patients in our sample reported less perceived social support in general and by their peers. Social contacts are of great importance for teenagers and young adults. Facilitating social relationships in order to increase well-being and QoL of this vulnerable group might be an important goal for psychosocial reintegration in patients after PHTX. Future studies should take a closer look at social relationships in this group, focusing on number of social relationships as well as quality and stability of their social networks.

PHTX patients reported a higher fatigue tendency than the control group, while no differences were found in other areas of physical complaints. Symptoms of fatigue might limit PHTX patients’ activities in daily life and hinder participation in social life, leisure activities and so on. This finding also warrants further investigation.

PHTX patients reported equal psychological well-being to the control group, which is a favourable result. However, they did report lower a physical QoL. In our exploratory regression models, we found that better perceived social support by peers predicts a better physical QoL, with a high proportion of explained variance. While these results further emphasise the importance of peer relations in this age group, the relationship between physical well-being and peer relations should be investigated further. Finally, we found that fewer physical complaints predict a better mental QoL, also with a large proportion of explained variance. In sum, PHTX patients fare well when it comes to their financial autonomy, relationship with their parents and profession, while they only rarely choose an academic career. They report lower social support in general and from peers and have more physical complaints (fatigue tendency) as well as reduced physical QoL, which both seem to be intertwined with social support from peers. While, on average, their mental well-being is comparable to that of the control group, fewer physical complaints predict higher scores on the mental well-being scale, also pointing to the key role of their physical health for other domains of functioning.

Limitations

Importantly, this study is cross-sectional, exploratory and comprised a small sample of PHTX patients. Accordingly, the results should be cautiously interpreted. Future studies investigating developmental challenges of PHTX patients during emerging adulthood should be longitudinal, in order to shed light on psychosocial adjustment after PHTX across time. Control groups should be carefully matched according to key variables. No correction for multiple testing was applied, as this study is exploratory and hypothesis-generating. Our results need to be interpreted accordingly and replicated in a confirmatory manner.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all participants for being a part of this study. The authors thank Anne Gale for editorial assistance, Hannah Tame for native speaker correction, Julia Stein and the Institute for Biometry and Clinical Epidemiology of the Charité Berlin for statistical advice and the ethics committee and the data protection registrar of the Charité Berlin for ethical and data protection advices. We acknowledge support from the German ResearchFoundation (DFG) and the Open Access Publication Fund of Charité –Universitätsmedizin Berlin.

Footnotes

Contributors: MS and WA made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work. MS and HF contributed to manuscript drafting and editing. MS, HF, VSUD and WA reviewed the protocol manuscript and made amendments. All authors critically reviewed and approved the final version. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Medical Ethics Committee Charité Mitte, Berlin, Germany (Nr. EA2/002/10).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

References

- 1.Kirklin JK. Current challenges in pediatric heart transplantation for congenital heart disease. Curr Opin Organ Transplant 2015;20:577–83. 10.1097/MOT.0000000000000238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rossano JW, Cherikh WS, Chambers DC, et al. . The registry of the international society for heart and lung transplantation: twentieth pediatric heart transplantation report-2017; focus theme: allograft ischemic time. J Heart Lung Transplant 2017;36:1060–9. 10.1016/j.healun.2017.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rossano JW, Dipchand AI, Edwards LB, et al. . The registry of the international society for heart and lung transplantation: nineteenth pediatric heart transplantation report-2016; focus theme: primary diagnostic indications for transplant. J Heart Lung Transplant 2016;35:1185–95. 10.1016/j.healun.2016.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.ISHLT. 2017; www.ishlt.org/registries/

- 5.Dipchand AI, Kirk R, Edwards LB, et al. . The registry of the international society for heart and lung transplantation: sixteenth official pediatric heart transplantation report–2013; focus theme: age. J Heart Lung Transplant 2013;32:979–88. 10.1016/j.healun.2013.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thrush PT, Hoffman TM. Pediatric heart transplantation-indications and outcomes in the current era. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:1080–96. 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.06.16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dipchand AI, Edwards LB, Kucheryavaya AY, et al. . The registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: seventeenth official pediatric heart transplantation report–2014; focus theme: retransplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 2014;33:985–95. 10.1016/j.healun.2014.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.ISHLT. ISHLT transplant registry quarterly reports for heart in Europe. 2018. http://www.ishlt.org/registries/quarterlyDataReportResults.asp?organ=HR&rptType=recip_p_surv&continent=3.

- 9.Tonsho M, Michel S, Ahmed Z, et al. . Heart transplantation: challenges facing the field. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2014;4:a015636 10.1101/cshperspect.a015636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pinquart M, Shen Y. Behavior problems in children and adolescents with chronic physical illness: a meta-analysis. J Pediatr Psychol 2011;36:1003–16. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsr042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pinquart M, Shen Y. Anxiety in children and adolescents with chronic physical illnesses: a meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr 2011;100:1069–76. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02223.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pinquart M, Shen Y. Depressive symptoms in children and adolescents with chronic physical illness: an updated meta-analysis. J Pediatr Psychol 2011;36:375–84. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsq104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calsbeek H, Rijken M, Bekkers MJ, et al. . Social position of adolescents with chronic digestive disorders. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2002;14:543–9. 10.1097/00042737-200205000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lindsay S. Employment status and work characteristics among adolescents with disabilities. Disabil Rehabil 2011;33:843–54. 10.3109/09638288.2010.514018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maslow GR, Haydon A, McRee AL, et al. . Growing up with a chronic illness: social success, educational/vocational distress. J Adolesc Health 2011;49:206–12. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stam H, Hartman EE, Deurloo JA, et al. . Young adult patients with a history of pediatric disease: impact on course of life and transition into adulthood. J Adolesc Health 2006;39:4–13. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peng DM, Zhang Y, Rosenthal DN, et al. . Impact of heart transplantation on the functional status of us children with end-stage heart failure. Circulation 2017;135:939–50. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeMaso DR, Twente AW, Spratt EG, et al. . Impact of psychologic functioning, medical severity, and family functioning in pediatric heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 199514():1102–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uzark KC, Sauer SN, Lawrence KS, et al. . The psychosocial impact of pediatric heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 199211:1160–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wray J, Radley-Smith R. Longitudinal assessment of psychological functioning in children after heart or heart-lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 2006;25:345–52. 10.1016/j.healun.2005.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Köllner V, Einsle F, Schade I, et al. . [The influence of anxiety, depression and post traumatic stress disorder on quality of life after thoracic organ transplantation]. Z Psychosom Med Psychother 2003;49:262–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wray J, Radley-Smith R. Beyond the first year after pediatric heart or heart-lung transplantation: Changes in cognitive function and behaviour. Pediatr Transplant 2005;9:170–7. 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2005.00265.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choudhry S, Dharnidharka VR, Castleberry CD, et al. . End-stage renal disease after pediatric heart transplantation: A 25-year national cohort study. J Heart Lung Transplant 2017. 10.1016/j.healun.2017.09.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rostad CA, Wehrheim K, Kirklin JK, et al. . Bacterial infections after pediatric heart transplantation: Epidemiology, risk factors and outcomes. J Heart Lung Transplant 2017;36:996–1003. 10.1016/j.healun.2017.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Copeland H, Razzouk A, Beckham A, et al. . Social framework of pediatric heart recipients who have survived more than 15 post-transplant years: A single-center experience. Pediatr Transplant 2017;21:e12853 10.1111/petr.12853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hollander SA, Chen S, Luikart H, et al. . Quality of life and metrics of achievement in long-term adult survivors of pediatric heart transplant. Pediatr Transplant 2015;19:76–81. 10.1111/petr.12384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mackie AS, Rempel GR, Islam S, et al. . Psychosocial maturity, autonomy, and transition readiness among young adults with congenital heart disease or a heart transplant. Congenit Heart Dis 201611:136–43. 10.1111/chd.12300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol 2000;55:469–80. 10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Havighurst RJ, Developmental tasks and education. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rauer AJ, Pettit GS, Lansford JE, et al. . Romantic relationship patterns in young adulthood and their developmental antecedents. Dev Psychol 2013;49:2159–71. 10.1037/a0031845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taylor SJ, Barker LA, Heavey L, et al. . The typical developmental trajectory of social and executive functions in late adolescence and early adulthood. Dev Psychol 2013;49:1253–65. 10.1037/a0029871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.White-Williams C, Grady KL, Naftel DC, et al. . The relationship of socio-demographic factors and satisfaction with social support at five and 10 yr after heart transplantation. Clin Transplant 201327:267–73. 10.1111/ctr.12057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fydrich T, Sommer G, Brähler E, et al. : Brähler E, Strauß B, F-SozU - Social support questionnaire. Göttingen: Hogrefe, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ravens-Sieberer U, Gosch A, Rajmil L, et al. . KIDSCREEN-52 quality-of-life measure for children and adolescents. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2005;5:353–64. 10.1586/14737167.5.3.353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bullinger M, Kirchberger I. SF-36 Fragebogen zum Gesundheitszustand Handanweisung. Göttingen: Hogrefe, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grady KL, Hof KV, Andrei AC, et al. . Pediatric Heart Transplantation: Transitioning to Adult Care (TRANSIT): baseline findings. Pediatr Cardiol 2018;39:354–64. 10.1007/s00246-017-1763-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.