Abstract

Objective

To assess the association of eczema with a patient’s subsequent risk of death from suicide. We hypothesised that persistent eczema would be associated with an increased risk for death from suicide.

Design

Double matched case–control study.

Setting

General population of Ontario, Canada.

Participants

Patients 15–55 years old. We identified cases of suicide from coroners’ reports between 1 January 1994 and 31 December 2014 and matched 1:2 with alive controls based on age, sex and socioeconomic status.

Exposure

The primary predictor was a history of persistent eczema, defined as five or more physician visits for the diagnosis over the preceding 5 years.

Main outcome and measure

Logistic regression to estimate the association between eczema and death from suicide.

Results

We identified 18 441 cases of suicide matched to 36 882 controls over the 21-year accrual period. Persistent eczema occurred in 174 (0.94%) suicide cases and 285 (0.77%) controls yielding a 22% increased risk of suicide associated with persistent eczema (OR 1.22, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.48, p=0.037). In mediation analyses, this association was largely explained through major suicide risk factors. Two-thirds of patients with eczema who died from suicide had visited a physician in the month before their death and one in eight had visited for eczema in the month before their death. Among patients who died by suicide, jumping and poisoning were relatively more frequent mechanisms among patients with eczema.

Conclusions

Patients with persistent eczema have a modestly increased subsequent risk of death from suicide, but this is not independent of overall mental health and the absolute risk is low. Physicians caring for these patients have opportunities to intervene for suicide prevention.

Keywords: dermatological epidemiology, eczema, epidemiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We conducted a large case–control study adequately powered to detect an association between eczema and suicide.

Universal insurance coverage for physician visits provide comprehensive data on physician visits preceding death from suicide.

We conducted several sensitivity analyses and tracer analyses with negative controls to test the robustness of results.

Our case definition of persistent eczema has not been validated so misclassification is a possibility.

Introduction

Eczema is a common skin disease associated with decreased quality of life comparable to many other chronic medical conditions.1 2 Eczema affects approximately 1 in 9 children and 1 in 14 adults, most of whom have mild disease.2–4 For patients with severe persistent eczema, however, the disease can be debilitating with severe itch, social embarrassment and impaired quality of life.5 Patients with eczema can also experience financial hardships due to direct medical costs, missed days from employment and decreased work productivity.5 6 Sleep loss related to itch can be especially debilitating2 7 and nearly half of US adults who have eczema with fatigue rate their health as poor or fair.2

Past research has linked eczema to mental illness. In a claims-based study from Taiwan, patients had a sevenfold increased risk of a major depressive disorder and fourfold increased risk of an anxiety disorder.8 In two American cross-sectional studies, eczema was associated with twice the risk of depression compared with the general population.9 One study from Denmark found no significant association between eczema and subsequent suicide.10 Whereas a prior study found a suicide risk twice the population norm for patients with eczema.11 The risk of suicide associated with eczema has not been assessed in North America; moreover, most studies have excluded youth despite eczema being distinctly common and suicide being a leading cause of death in this age group.2 4 12

The objective of this case–control study was to assess the association of eczema with a patient’s subsequent risk of death from suicide. A secondary aim was to assess the recency of physician visits prior to suicide among patients with eczema. A randomised controlled trial was deemed impossible because patients cannot be assigned a diagnosis of eczema; therefore, we conducted a large-scale multiyear observational analysis of longitudinal individual patient data. We hypothesised that persistent eczema would increase a patient’s risk of death from suicide and that many deaths would be preceded by a recent physician visit. If true, this would suggest that preventive efforts targeting vulnerable patients might save lives.

Patient and public involvement

There was no patient or public involvement in this study.

Selection of patients

We conducted a double matched case–control study of patients between the age of 15 and 55 years in Ontario. We included individuals 15 and older as eczema is a common diagnosis and suicide is a common cause of death in youth.2 4 12 We excluded adults older than 55 to avoid misclassification of age-associated xerosis with itch as eczema. Cases of suicide were identified from the Ontario Vital Statistics Database from 1 January 1994 to 31 December 2014, representing all available data. We defined suicide using International Classification of Disease (ICD) codes (ICD-9 E950–E959, E980–E987; ICD-10×60–X84, Y10–Y32, Y34).13–15 Inter-rater agreement from coroners on suicide diagnosis was high and showed 97% concordance with the vital statistics database.16 17 We also extracted data on the mechanism of suicide in five categories as asphyxiation, jumping, poisoning, violence and miscellaneous.

Controls were selected from the general population in Ontario using the Registered Persons Database that identified all patients insured under the Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP).18 For each case of suicide, we selected two control patients from the general population matched on age (within 2 days), socioeconomic status (SES) quintile and sex using simple random selection when excess matches were available. All cases and controls were alive and eligible for OHIP coverage on the index date and 1 year prior. SES at the index date was estimated from the Statistics Canada algorithm based on neighbourhood income19 20 and patients with missing SES were matched to controls who were also missing SES. As a result, we obtained exact triplets of one case matched to two controls with no missing matches. These datasets were linked using unique encoded identifiers and analysed at Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences.

Primary predictor

We used a 5-year look-back interval to assess each patient through a consistent ascertainment interval for cases and controls. The matching date in each triplet of patients was defined as the date of suicide death of the case. Prior medical care for each patient was evaluated based on physician diagnoses documented as ICD-9 diagnostic codes.13 In Ontario, physicians document each encounter with a single ICD-9 code. Eczema was defined using diagnosis code 691.13 In another population, ICD-9 codes for atopic dermatitis, a specific subtype of eczema, had a positive predictive value of 50% based on a requirement for two or more ICD-9 codes to identify cases of probable atopic dermatitis.21 To increase the specificity and to define persistent eczema, we required five or more physician visits for the diagnosis, each separated by at least 1 week over the 5-year look-back interval. Given the uncertain validity of that definition, we refer to our predictor as ‘eczema’ rather than the more specific ‘atopic dermatitis’ throughout the manuscript.

Additional patient characteristics

Specific additional medical diagnoses (asthma, hay fever or rhinitis, alcoholism, drug dependence, tobacco abuse, sleep and other disorders, depression, anxiety disorders, psychoses, personality disorders, malignancy, benign skin tumours, psoriasis) were identified during the 5-year look-back interval using ICD-9 codes in the OHIP database. Measures of overall healthcare resource utilisation were obtained from the OHIP database, the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System and the Discharge Abstract Database (counts of clinic visits, emergency room visits, hospitalisations in the prior year). We collected data on patients’ most recent healthcare visit, the specialty of the physician and the associated diagnosis. We also collected data on the timing of suicide (proximity to the most recent visit with a dermatologist or psychiatrist and recency of a visit for eczema).

Statistical analysis

We used logistic regression to calculate ORs with 95% CIs for the association of persistent eczema with the risk of subsequent death from suicide. We examined the robustness of findings by additionally calculating associations using conditional logistic regression to fully account for matching. To assess for potential mediation, we conducted stratified analyses by major suicide risk factors (depression, psychoses, personality disorders, sleep and other disorders, drug dependence and alcoholism) within triads of cases and controls. Further, we used logistic regression with suicide as the outcome and major suicide risk factors as covariates to derive an overall suicide predilection score. We then conducted logistic regression stratified by low (at or below the median) or high (above the median) overall suicide predilection score. To assess for potential mediation or confounding by a major atopic comorbidity, we conducted analyses further stratified by history of asthma.

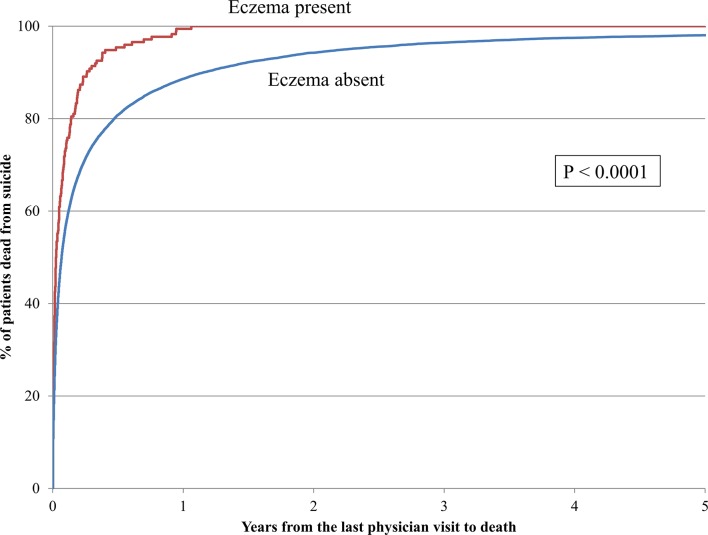

We plotted Kaplan-Meier curves for patients who died from suicide with and without persistent eczema to assess the time interval between the most recent physician visit and ultimate suicide. We compared the two curves using the logrank test. To assess potential differences in the mechanism of suicide between patients with and without persistent eczema, we calculated descriptive ORs with 95% CIs for the different categories of suicide with no prespecified hypotheses.

We conducted several sensitivity analyses as tests of robustness. We replicated separate analyses to check results using alternative definitions of eczema: (1) spanning between 1 and 10 claims associated with the diagnosis; (2) requiring a comorbid atopic condition (asthma or rhinitis) and (3) excluding patients who had a history of stasis ulcers, varicose veins, lymphoedema, contact dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis or psoriasis. These latter two analyses were based on the rationale that comorbid asthma and rhinitis can improve the positive predictive value of ICD codes for atopic dermatitis21 and because excluding commonly confused conditions can also decrease false positive cases.

As a test for residual confounding, we conducted tracer analyses with two additional control predictors: benign skin tumours and psoriasis (another chronic skin disease with effective treatment options). We anticipated benign skin tumours and psoriasis might not be associated with an increased risk for suicide and thereby validate the distinctive association with eczema.

Results

We identified 18 441 cases of suicide matched to 36 882 alive controls over the 21-year accrual period. The median patient age was 38 years, 74% were male and the average SES was below the population median. Mental health disorders were more common among patients who had died from suicide than among controls, as were malignant neoplasms and asthma (table 1). Patients who died from suicide had more clinic visits, emergency department visits and inpatient admissions in the year prior to the index date than controls.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Suicide cases n=18 441, (%) |

Matched controls n=36 882, (%) |

|

| Age (years) | ||

| 15–24 | 2825 (15) | 5650 (15) |

| 25–34 | 3746 (20) | 7492 (20) |

| 35–44 | 5595 (30) | 11 190 (30) |

| 45–55 | 6275 (34) | 12 550 (34) |

| Sex (male) | 13 680 (74) | 27 360 (74) |

| Income quintile | ||

| Q5 (highest) | 2839 (15) | 5678 (15) |

| Q4 | 3162 (17) | 6324 (17) |

| Q3 | 3426 (19) | 6852 (19) |

| Q2 | 3814 (21) | 7628 (21) |

| Q1 (lowest) | 4969 (27) | 9938 (27) |

| Unknown/suppressed | 231 (1) | 462 (1) |

| Home location | ||

| Urban | 15 532 (84) | 32 158 (87) |

| Rural* | 2893 (15) | 4462 (12) |

| Missing | 16 (<1) | 262 (1) |

| Comorbidities† | ||

| Alcoholism | 3109 (17) | 750 (2) |

| Drug dependence/addiction | 3645 (20) | 1164 (3) |

| Psychoses | 5373 (29) | 979 (3) |

| Depression | 5753 (31) | 1788 (5) |

| Anxiety disorder | 12 807 (69) | 10 690 (29) |

| Personality disorder | 2391 (13) | 469 (1) |

| Sleep disorders | 2844 (15) | 2536 (7) |

| Malignancy | 1024 (6) | 1331 (4) |

| Asthma | 2291 (12) | 3247 (9) |

| Rhinitis | 1956 (11) | 4204 (11) |

| Health services use in the preceding year | ||

| Six or more clinic visits | 11 946 (65) | 12 365 (34) |

| One or more emergency room visits | 4053 (22) | 3173 (9) |

| One or more inpatient admissions | 1379 (8) | 511 (1) |

| OHIP eligible for entire 5-year look-back period | 17 701 (96) | 34 447 (93) |

*Rural includes unknown/suppressed home location.

†Comorbidities defined by truncated ICD-9 codes: alcoholism (303), drug dependence/addiction (304), psychoses (291, 292, 295, 296, 298, 299), depression (311), anxiety disorder (300), personality disorder (301), sleep and other disorders (307), malignancy (140–165, 170–175, 179–208), asthma (493), rhinitis (477).

ICD-9, International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision; OHIP, Ontario Health Insurance Plan.

A history of persistent eczema occurred in 174 (0.94%) suicide cases and 285 (0.77%) controls. In univariate analysis, persistent eczema was associated with a 22% increased risk of suicide. Results were identical for ordinary and conditional logistic regression (OR 1.22, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.48, p=0.037). The net increase was equal to 31 excess cases of suicide associated with eczema (more than one patient per year).

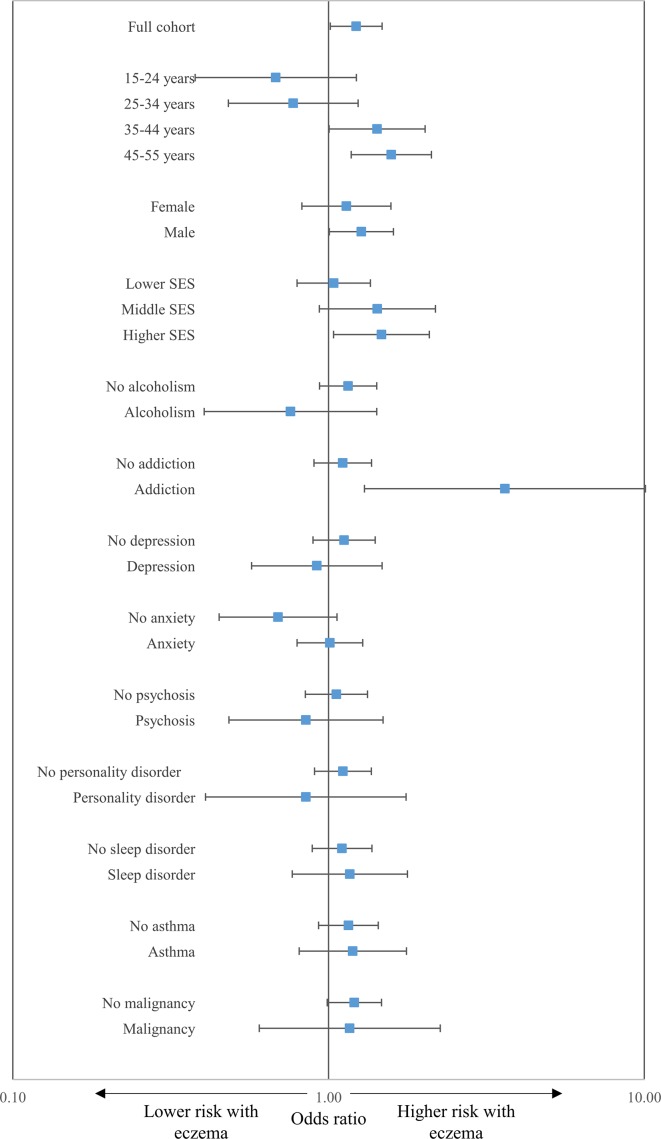

Stratified analyses showed the association of eczema with suicide was accentuated among older men with a history of addiction (figure 1). There was no significant differential association of eczema with suicide between strata of patients with and without asthma, malignancy or other individual suicide risk factors such as depression.

Figure 1.

Relative risk of suicide associated with persistent eczema. Forest plot showing relative increase in risk of suicide among patients with persistent eczema compared with patients without persistent eczema. The x-axis shows OR on a logarithmic scale where values more than 1.0 denote increased risk. The y-axis shows specific subgroups of patients with the overall cohort positioned lowest. Squares indicate point estimates and horizontal lines 95% CIs. Main findings are an increase in risk associated with eczema with accentuation of risk among older men, those with mid-to-high socioeconomic status (SES) and a history of addiction.

Patients with eczema had significantly higher suicide predilection scores compared with patients without eczema (median 0.32 vs 0.15, p<0.0001; online supplementary figure 1). Comparisons based on mean scores showed similar imbalance (0.42 vs 0.33, p<0.0001). The highest decile of suicide predilection score was nearly twice as common among patients with eczema as controls (17% vs 10%, p<0.0001). Stratified analysis by high or low predilection scores showed no significant further association of eczema with suicide between patients with high predilection scores (OR 0.97, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.22, p=0.81) and low predilection scores (OR 0.59, 95% CI 0.34 to 1.03, p=0.06), suggesting that eczema was not an independent contributor to suicide risk beyond its influence on mental health risk overall.

bmjopen-2018-023776supp001.pdf (170.3KB, pdf)

Nearly all patients with persistent eczema who died from suicide had visited a physician in the year prior to their death, 67% within a month and 37% within a week. Among patients who died from suicide, those diagnosed with persistent eczema visited a physician more recently than patients without persistent eczema (p<0.0001, figure 2). For both patients with and without persistent eczema who died from suicide, the most recent physician visit was most frequently with a family physician (table 2). Among patients with persistent eczema, 1 in 25 had visited a dermatologist last. For 1 in 16 patients with persistent eczema who died from suicide, their last visit was for eczema. We found no meaningful differences in season or in day of the week of death distinguishing patients who did and did not have persistent eczema (table 3).

Figure 2.

Time from the most recent physician visit to suicide. Kaplan-Meier curve shows the time between the last physician visit and subsequent death from suicide (n=18 441). The x-axis shows the time in years lapsed between the most recent physician visit and the date of death. The y-axis shows the per cent of patients dead from suicide. The red line represents patients with persistent eczema. The blue line represents patients without persistent eczema. Statistical significance was based on the logrank test. Main findings show that patients with persistent eczema were more likely to see a physician in close proximity to their death.

Table 2.

Description of the most recent physician visit among patients who died from suicide

| Persistent eczema present n=174 patients, (%) |

Persistent eczema absent n=18 267 patients, (%) |

|

| Physician specialty of most recent visit | ||

| Family practice | 121 (48) | 13 320 (55) |

| Dermatology | 9 (4) | 125 (1) |

| Psychiatry | 31 (12) | 3101 (13) |

| Other* | 93 (37) | 7618 (32) |

| Diagnosis associated with most recent visit | ||

| Eczema | 16 (6) | 129 (1) |

| Mental disorders† | 72 (28) | 7754 (32) |

| Other medical diagnosis‡ | 166 (65) | 16 281 (67) |

| Total no of billing claims§ | 254 | 24 164 |

Results are presented as the number of billing claims (%).

*Includes paediatrician visits.

†Includes disorders of substance use.

‡Includes cases for which no diagnosis is listed.

§For some patients, more than one billing claim is included if they occurred on the same day.

Table 3.

Timing and mechanism of death from suicide among patients with and without a history of persistent eczema

| Persistent eczema present n=174 patients, (%) |

Persistent eczema absent n=18 267 patients, (%) |

|

| Time from last psychiatrist visit | ||

| ≤1 month | 40 (23) | 3371 (19) |

| >1 month or no visit | 134 (77) | 14 896 (82) |

| Time from last dermatologist visit | ||

| ≤1 month | 8 (5) | 98 (<1) |

| >1 month or no visit | 166 (95) | 18 169 (>99) |

| Time from last visit for eczema | ||

| ≤1 month | 14 (8) | 83 (<1) |

| >1 month or no visit | 160 (92) | 18 184 (>99) |

| Season | ||

| Spring | 45 (26) | 4756 (26) |

| Summer | 50 (29) | 4812 (26) |

| Autumn | 36 (21) | 4515 (25) |

| Winter | 43 (25) | 4184 (23) |

| Day | ||

| Weekday | 125 (72) | 13 242 (73) |

| Weekend | 49 (28) | 5025 (28) |

| Mechanism of death | ||

| Asphyxiation | 40 (23) | 6460 (35) |

| Jumping | 24 (14) | 1439 (8) |

| Poisoning | 68 (39) | 5715 (31) |

| Violent | 31 (18) | 3144 (17) |

| Miscellaneous* | 11 (6) | 1504 (8) |

Poisoning deaths include deaths caused by prescription and non-prescription and illicit and legal substances. Violent deaths include those caused by firearms or other weapons.

*Includes mechanisms listed as uncertain.

Analyses of suicide cases showed diverse mechanisms, of which about 8% were unclassified due to uncertain, multifactorial or missing details. Asphyxiation was the most common single cause of suicide and was less frequent among individuals who had persistent eczema than controls (OR 0.55, 95% CI 0.38 to 0.78, p=0.0008). In contrast, jumping from a vertical height had the largest relative increased risk among patients who had persistent eczema (OR 1.87, 95% CI 1.21 to 2.89, p=0.0047). Poisoning was the second largest relative increased risk among patients who had persistent eczema (OR 1.41, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.91, p=0.03). Violent forms of suicide were infrequent and generally balanced between the two groups (OR 1.04, 95% CI 0.71 to 1.54, p=0.83).

In sensitivity analyses requiring fewer than five visits for eczema to define the predictor, the association with suicide was somewhat attenuated (online supplementary figure 2). When 10 or more visits for eczema were required, the CIs widened substantially and the association was ambiguous. When a diagnosis of asthma or rhinitis was required to identify cases of eczema, the estimated association for the risk of suicide was similar to the primary analysis but not statistically significant (OR 1.26, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.69, p=0.12). When patients who had a diagnosis of stasis ulcers, varicose veins, lymphoedema, contact dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis and psoriasis were excluded, the results were similar to the primary analysis (OR 1.26, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.61, p=0.06), although not statistically significant. Benign skin tumours were associated with no increase in suicide risk (OR 0.90, 95% CI 0.84 to 0.97, p=0.008). Psoriasis was associated with an equivocal increase in suicide risk (OR 1.14, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.31, p=0.06).

Discussion

In this large longitudinal case–control study, persistent eczema was associated with a modestly increased risk of subsequent death from suicide. The absolute risk was low. The association was fully explained by mental health disorders including depression, anxiety, sleep disorders and substance misuse, suggesting that eczema was not an independent contributor to suicide risk beyond its influence on mental health risk overall. The patient group at highest risk was older men with a history of addiction. Asphyxiation was the most common mechanism of suicide death overall, but poisoning and jumping were differentially increased for patients with persistent eczema. Patients with eczema who died from suicide usually had visited a physician in the month before death.

Our study is in agreement with other literature on the association of eczema with adverse mental health. A Norwegian study found that young adults with eczema and itchy skin had a 24% prevalence of suicidal ideation in the preceding week.7 Only two studies have examined the risk of death from suicide associated with eczema, with mixed results. One conducted using administrative data for adults in Denmark found that patients with eczema had a 71% increased risk of suicide attempts and double the risk of death from suicide, (a more prominent association than in our study).11 Similar to our findings, older adults with eczema had a further accentuated risk. It is unclear why the association might be increased in older populations and one possible explanation could be the cumulative stress of living with a chronic condition for decades. The only other past study, also from Denmark, found no statistically significant association between eczema and suicide.10

Our study contains novel findings concerning physician visits by patients with atopic dermatitis prior to suicide. Nearly two in five patients with eczema who died from suicide contacted a physician in the week before their death. The most recent physician visit was most commonly with a general practitioner and often for reasons related to mental health. In a small number of patients, the most recent physician contact was for their eczema. While dermatologists tend to under-recognise depression and anxiety in their patients, all clinicians should recognise psychological distress.22 Patients with eczema who present with signs of significant mental health distress could be assessed for suicide risk. In particular, standardised tools have been suggested for assessing suicide risk in dermatology clinics, but have not been formally evaluated in that setting.23 24

Asphyxiation is a frequent mechanism of suicide yet was relatively uncommon among patients with persistent eczema. Instead, patients with eczema were comparatively more prone to die by jumping from tall heights or self-poisoning. The significance of these patterns is unclear. One possibility is that patients with eczema have high rates of medical and psychiatric comorbidity relative to the general population and are more likely to have access to prescription drugs with the potential to cause death. Another interpretation is that asphyxiation is a more prolonged and painful means of suicide so that patients with eczema who live in discomfort from their condition choose rapid or less painful means of dying. A greater understanding is needed for future research.

The generalisability of our study is limited to a single large region in a high-income country with universal healthcare access. Specifically, comprehensive medical care in our patients may have substantially mitigated some of the suicide risk associated with eczema. In addition, we lacked data on eczema severity, social isolation, other life stresses or risk factors for suicide completion such as suicidal ideation.25 We also lack data on treatments used for eczema, which can be used to stratify eczema cases based on severity and which may be important given the psychiatric effects of systemic corticosteroids.10 26 Our primary outcome examined an extreme indicator of mental suffering and the overall observed effect size was more modest than previously reported for other medical illnesses.27 While only a small minority of patients with eczema die by suicide, many more suffer from non-lethal forms of depression and other mental disorders.8–10 28

The most important limitation of our study relates to our definition of persistent eczema. A past report suggested that two or more ICD-9 codes for atopic dermatitis have a 50% positive predictive value for probable atopic dermatitis.21 The true positive predictive value may be higher than reported in that study, as it used stringent clinical diagnostic criteria unsuitable in a retrospective study. Nevertheless, misclassification of persistent eczema cases is a strong possibility and may have impacted our results in a number of ways. Random misclassification may cause underestimates of the magnitude of associations.29 Misclassification of less severe skin diseases such as contact dermatitis could also bias our findings towards the null. However, misclassification of more severe skin diseases such as an exfoliative dermatitis may bias our results towards an increased risk for suicide. It is unclear whether our requirement of five occurrences of code 691 increases or decreases the accuracy of our case definition for identifying cases of atopic dermatitis and exactly what impact this had on the results.

To provide some additional nuances for our case definition, we calculated the prevalence of asthma and rhinitis among patients in our study and found each of these atopic comorbidities was more than twice as common among those with persistent eczema compared with those without (online supplementary table 1). It is possible that the associations observed between our primary predictor and these well-known atopic comorbidities are partially confounded by differential healthcare system access. However, the strong associations seen support the notion that our predictor definition represents, to some extent, persistent atopic dermatitis. Our sensitivity analyses requiring comorbid asthma or rhinitis to define eczema and excluding patients with psoriasis and other skin diseases yielded decreased sample sizes and showed results that were no longer significant. We are reassured that the estimates were largely unchanged and are cautious not to overinterpret statistical significance in post hoc secondary analyses. Nevertheless, due to the uncertain validity of our primary predictor, we use the non-specific term ‘eczema’ throughout the manuscript.

Strengths of our study include the large sample of suicide deaths, the known validity of suicide outcomes and our double-matched case–control design. As Ontario has a universal health insurance programme, we were able to comprehensively identify all physician visits prior to death. Of course, patients who had persistent eczema but who did not engage with the healthcare system may have been missed. In summary, patients with persistent eczema have a modestly increased subsequent risk of death from suicide. Physicians may have opportunities to intervene for suicide prevention in this vulnerable patient population.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: AMD and DAR designed and obtained funding for the study. DT performed data analysis. AMD drafted the manuscript and all authors contributed to critical revision of the manuscript. DAR accepts full responsibility for the work, the conduct of the study, had access to the data, and the decision to publish. AMD attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: This study was supported in part by research grants from the National Eczema Association and Eczema Society of Canada. DAR receives funding from the Government of Canada through a Canada Research Chair in Medical Decision Sciences. This study was supported by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES), which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). No endorsement by ICES or the Ontario MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred.

Disclaimer: The funders had no role in the design, conduct or decision to publish this study. The opinions, results and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources.

Competing interests: AMD served as an investigator and has received research funding from Sanofi and Regeneron and has been a consultant for Sanofi, RTI Health Solutions, Eczema Society of Canada and the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. He has received honoraria from Astellas Canada, Prime, Spire Learning, CME Outfitters and Eczema Society of Canada.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES) and the Women’s College Hospital Research Ethics Board deemed the work exempt from supplementary ethics review.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There is no plan to share raw data from this study.

References

- 1. Kiebert G, Sorensen SV, Revicki D, et al. . Atopic dermatitis is associated with a decrement in health-related quality of life. Int J Dermatol 2002;41:151–8. 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01436.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Silverberg JI, Garg NK, Paller AS, et al. . Sleep disturbances in adults with eczema are associated with impaired overall health: a US population-based study. J Invest Dermatol 2015;135:56–66. 10.1038/jid.2014.325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Weidinger S, Novak N. Atopic dermatitis. The Lancet 2016;387:1109–22. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00149-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shaw TE, Currie GP, Koudelka CW, et al. . Eczema prevalence in the United States: data from the 2003 National Survey of Children’s Health. J Invest Dermatol 2011;131:67–73. 10.1038/jid.2010.251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Eckert L, Gupta S, Amand C, et al. . Impact of atopic dermatitis on health-related quality of life and productivity in adults in the United States: An analysis using the National Health and Wellness Survey. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017;77:274–9. 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Eckert L, Gupta S, Amand C, et al. . The burden of atopic dermatitis in US adults: Health care resource utilization data from the 2013 National Health and Wellness Survey. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018;78:54–61. 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Halvorsen JA, Lien L, Dalgard F, et al. . Suicidal ideation, mental health problems, and social function in adolescents with eczema: a population-based study. J Invest Dermatol 2014;134:1847–54. 10.1038/jid.2014.70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cheng CM, Hsu JW, Huang KL, et al. . Risk of developing major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders among adolescents and adults with atopic dermatitis: a nationwide longitudinal study. J Affect Disord 2015;178:60–5. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.02.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yu SH, Silverberg JI. Association between atopic dermatitis and depression in US Adults. J Invest Dermatol 2015;135:3183–6. 10.1038/jid.2015.337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thyssen JP, Hamann CR, Linneberg A, et al. . Atopic dermatitis is associated with anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation, but not with psychiatric hospitalization or suicide. Allergy 2018;73:214–20. 10.1111/all.13231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Egeberg A, Hansen PR, Gislason GH, et al. . Risk of self-harm and nonfatal suicide attempts, and completed suicide in patients with psoriasis: a population-based cohort study. Br J Dermatol 2016;175:493–500. 10.1111/bjd.14633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Leung DY. Infection in atopic dermatitis. Curr Opin Pediatr 2003;15:399–404. 10.1097/00008480-200308000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. WHO. International classification of diseases. 9th revision Geneva: WHO, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 14. WHO. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. 10th revision Geneva: World Health Organization, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Thomas KH, Davies N, Metcalfe C, et al. . Validation of suicide and self-harm records in the Clinical Practice Research Datalink. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2013;76:145–57. 10.1111/bcp.12059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Parai JL, Kreiger N, Tomlinson G, et al. . The validity of the certification of manner of death by Ontario coroners. Ann Epidemiol 2006;16:805–11. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gatov E, Kurdyak P, Sinyor M, et al. . Comparison of vital statistics definitions of suicide against a coroner reference standard: a population-based linkage study. Can J Psychiatry 2018;63:152–60. 10.1177/0706743717737033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ardal S. Health analyst’s toolkit. Toronto, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Glazier RH, Creatore MI, Agha MM, et al. . Socioeconomic misclassification in Ontario’s Health Care Registry. Can J Public Health 2003;94:140–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wilkins R. Use of postal codes and addresses in the analysis of health data. Health Rep 1993;5:157–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hsu DY, Dalal P, Sable KA, et al. . Validation of International Classification of Disease Ninth Revision codes for atopic dermatitis. Allergy 2017;72:1091–5. 10.1111/all.13113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dalgard FJ, Svensson Å, Gieler U, et al. . Dermatologists across Europe underestimate depression and anxiety: results from 3635 dermatological consultations. Br J Dermatol 2018;179:464–70. 10.1111/bjd.16250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McDonald K, Shelley A, Jafferany M. The PHQ-2 in Dermatology-Standardized Screening for Depression and Suicidal Ideation. JAMA Dermatol 2018;154:139–41. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.5540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care 2003;41:1284–92. 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Beghi M, Rosenbaum JF, Cerri C, et al. . Risk factors for fatal and nonfatal repetition of suicide attempts: a literature review. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2013;9:1725–36. 10.2147/NDT.S40213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kershner P, Wang-Cheng R. Psychiatric side effects of steroid therapy. Psychosomatics 1989;30:135–9. 10.1016/S0033-3182(89)72293-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Juurlink DN, Herrmann N, Szalai JP, et al. . Medical illness and the risk of suicide in the elderly. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:1179–84. 10.1001/archinte.164.11.1179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bostwick JM, Pabbati C, Geske JR, et al. . Suicide attempt as a risk factor for completed suicide: even more lethal than we knew. Am J Psychiatry 2016;173:1094–100. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15070854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Delgado-Rodríguez M, Llorca J. Bias. J Epidemiol Community Health 2004;58:635–41. 10.1136/jech.2003.008466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-023776supp001.pdf (170.3KB, pdf)