Abstract

Animal cells use an unknown mechanism to control their growth and physical size. Here, using the fluorescence exclusion method, we measure cell volume for adherent cells on substrates of varying stiffness. We discover that the cell volume has a complex dependence on substrate stiffness and is positively correlated with the size of the cell adhesion to the substrate. From a mechanical force–balance condition that determines the geometry of the cell surface, we find that the observed cell volume variation can be predicted quantitatively from the distribution of active myosin through the cell cortex. To connect cell mechanical tension with cell size homeostasis, we quantified the nuclear localization of YAP/TAZ, a transcription factor involved in cell growth and proliferation. We find that the level of nuclear YAP/TAZ is positively correlated with the average cell volume. Moreover, the level of nuclear YAP/TAZ is also connected to cell tension, as measured by the amount of phosphorylated myosin. Cells with greater apical tension tend to have higher levels of nuclear YAP/TAZ and a larger cell volume. These results point to a size-sensing mechanism based on mechanical tension: the cell tension increases as the cell grows, and increasing tension feeds back biochemically to growth and proliferation control.

INTRODUCTION

What determines the physical volume of a cell? Despite the fundamental importance of this question, and decades of experimental studies on growth dynamics in mammalian cells (Killander and Zetterberg, 1965; Fox and Pardee, 1970; Yen et al., 1975; Brooks and Shields, 1985; Hola and Riley, 1987; Conlon and Raff, 2003; Godin et al., 2010; Son et al., 2012), the mechanisms behind cell volume regulation are not well understood (Ginzberg et al., 2015). It is known that different cell types from the same organism can have dramatically different volumes (Ginzberg et al., 2015), but how cells sense and control growth/division rates under different conditions is not clear. From genetic studies, several pathways have been implicated in cell volume control. The mTor signaling pathway is known to regulate cell size by stimulating anabolism and inhibiting catabolism (Schmelzle and Hall, 2000; Lloyd, 2013). Similarly, the mammalian version of the Hippo pathway and its downstream effector YAP/TAZ are important in controlling tissue and organ size and have been implicated in cell volume regulation (Dong et al., 2007; Saucedo and Edgar, 2007; Zhao et al., 2011; Yu et al., 2015). While studies have suggested that there is a cell size checkpoint within the cell cycle at transition from G1 to S, which determines the added cell volume (Ginzberg et al., 2015; Varsano et al., 2017), exactly how and what signaling pathways are connected with the size checkpoint is still unclear.

Working from a different perspective, cells are active mechanical objects that form adhesions with the extracellular matrix and balance forces in the cytoplasm with the extracellular environment (Tao et al., 2017). Mechanical properties of the microenvironment have been shown to influence cell growth– and cycle–related phenomena including differentiation (Engler et al., 2006) and may impact cell volume as well. Indeed, YAP/TAZ has been shown to be sensitive to mechanical forces and the stiffness of the environment (Dupont et al., 2011; Codelia et al., 2014; Low et al., 2014; Piccolo et al., 2014; Elosegui-Artola et al., 2016), which suggests that the mechanical state of the cell could influence cell growth and volume. In this paper, we explore how cytoskeletal tension is related to cell volume and how substrate stiffness influences cell size through the measurement of single cell volumes for several different cell types. We show that how cells distribute their tension over different regions of the cell surface can explain the observed cell volume under different conditions. Moreover, we explore how single cell tension (reported by the amount of phosphorylated myosin light chain [pMLC], similarly to previous work; Fernandez-Gonzalez and Zallen, 2009; Elliott et al., 2015) is related to YAP/TAZ nuclear localization and discover that the amount of nuclear YAP/TAZ, which is also the active form, is correlated with the amount of myosin in the apical region of the adherent cell. This is consistent with suggestions that YAP is sensitive to cytoskeletal tension (Dupont et al., 2011; Elosegui-Artola et al., 2016). The level of nuclear YAP/TAZ also increases with increasing cell volume, suggesting that as the cell grows, it increases myosin activity to maintain force balance, and the change in the myosin level can serve as a signal for YAP/TAZ activity, which influences the observed cell size.

Several methods have been used to measure cell volume (Hurley, 1970; Tzur et al., 2009; Sung et al., 2013; Cadart et al., 2017). Here we are interested in a high-throughput measurement of live cell volume for single adherent cells. We use the fluorescence exclusion method (Bottier et al., 2011; Cadart et al., 2017) to quantify cell volume. The fluorescence exclusion method was able to reveal that mitotic cells swell before cytokinesis (Son et al., 2015; Zlotek-Zlotkiewicz et al., 2015). We simultaneously measure cell volume, cell adhesion area, and cell shape factor for three different cell types on substrates varying in stiffness from 3 kPa to GPa (glass). The results show that the mean cell volume depends on the substrate stiffness, but that dependence varies across different cell types. For all cells, the measured volume is strongly correlated with cell adhesion area, but the slope of this correlation depends on the adhesion shape and the substrate stiffness. For the same adhesion area, more elongated cells have a smaller volume than more circular cells. This result can be explained by a mechanical model of the cell where cortical tension developed by myosin is proportional to the mean curvature of the cell surface. In addition, from quantitative immunofluorescence measurements, we find that the total pMLC content and the spatial distribution of pMLC can predict cell volume. Using the measured pMLC levels as inputs, our mechanical model can be used to predict cell volume across all cell types on all substrates.

Cytoskeletal tension and substrate stiffness have been shown to influence the nuclear localization of YAP/TAZ (Dupont et al., 2011; Codelia et al., 2014; Low et al., 2014; Piccolo et al., 2014; Elosegui-Artola et al., 2016), which in turn influences cell proliferation and growth (Shen and Stanger, 2015). The nuclear portion of YAP/TAZ is a cofactor with TEAD and regulates the transcription of a large group of proteins (Zhao et al., 2008). To explore how cell tension is related to YAP/TAZ nuclear localization, we performed quantitative immunofluorescence measurements. While the results show dependence on cell type, for the terminally differentiated cells tested, we observed that the average cell volume is positively correlated with the level of nuclear YAP/TAZ. But the nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio of YAP/TAZ is not a predictor of cell volume. The nuclear YAP/TAZ level is also positively correlated with the amount of apical pMLC, a readout of apical cell tension. In mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), the behavior of YAP and tension is more complex, but the correlation between nuclear YAP/TAZ and apical pMLC persists. These results suggest that cell tension can potentially serve as a checkpoint signal that allows the cell to sense its volume and control the cell cycle progression in late G1.

RESULTS

Cell volume is heterogeneous and depends on substrate stiffness

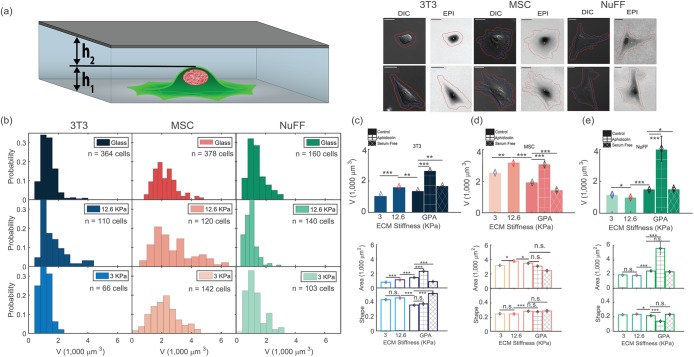

To quantify cell volume in different physical and biochemical environments, we use the fluorescence exclusion method to simultaneously measure single-cell volume, adhesion area, and cell shape for three different fibroblastic cell types (Figure 1a). We compare common mouse fibroblasts (3T3) with human-isolated fibroblasts (NuFF) and mouse-isolated mesenchymal stem cells (MSC). 3T3 fibroblasts are from the standard NIH line. NuFFs are neonatal foreskin fibroblasts obtained from Global Stem (Rockville, MD) at passage 9 and used up to passage 28. MSCs were isolated from bone marrow of 6 wk–old mice. Volume measurements were performed for cells at low density and on substrates of 3-kPa PDMS, 12.6-kPa PDMS, and glass (gigapascals). We also tried 0.4-kPa PDMS substrates, but found them to be too soft to form stable microfluidic channels for volume measurement. In addition, we measured cell volume during cell cycle arrest achieved through serum starvation or treatment with aphidicolin on glass substrates. The resultant cell volume measurements displayed in Figure 1, b–e, show several striking features. 1) Individual cell volume in each condition always shows significant heterogeneity, with a high proportion of smaller cells (Figure 1b). This is in accord with previous results using a different method of measurement (Tzur et al., 2009). This heterogeneity is partly explained by the fact that cells are in different stages of the cell cycle, and cells divide symmetrically, producing two daughter cells, so that there are more young cells than old cells. The shape of the volume distributions can be roughly explained theoretically from cell aging dynamics (Stukalin et al., 2013). 2) The average cell volume varies significantly across cell types, the largest line tested being the MSCs. The average cell volume also depends on the substrate stiffness. In particular, the 12.6-kPa substrate always shows a significant deviation, indicating unusual behavior at intermediate stiffness. For 3T3s and MSCs, the average cell volume at 12.6 kPa is 32 and 50% higher than on 3 kPa and glass, respectively. For NuFFs, it is 40 and 15% less than on glass and 3 kPa, respectively (Figure 1, c–e). The sharp variation around intermediate stiffness is surprising, but parallels previous work that showed a similar change in cell adhesion shape (Rehfeldt et al., 2012) and traction force (Han et al., 2012) at intermediate stiffness. The overall trend of these results is in agreement with results previously published (Wang et al., 2018) on the MCF7 cell line, and is somewhat different from confocal microscopy results for cells on polyacrylamide gels (Guo et al., 2017), presumably due to the difference in substrate material and coating. 3) Cell cycle arrest using serum starvation and aphidicolin produced significant changes in average cell volume as well (Figure 1, c–e). Cells after serum starvation can be smaller, while aphidicolin-treated cells can be significantly larger. Aphidicolin inhibits DNA polymerase and arrests cells in late G1 and early S (Krokan et al., 1981). From DNA staining measurements, we observe that these cells all have a single copy of DNA (unpublished data), suggesting that they have stopped copying their DNA (Supplemental Figure S8, a–c), but perhaps continue to accumulate cell mass.

FIGURE 1:

Cell volume is heterogeneous and depends on substrate stiffness. (a) Diagram of the microfluidic channel used for fluorescence-exclusion cell-volume measurements. The channel height is h1 + h2 = 15 μm. The fluorescence signal is directly proportional to h2, and the total integrated fluorescence signal after background subtraction gives the cell volume. Images of 3T3, NuFF, and MSC cells in the microfluidic device show DIC and fluorescent channels. The DIC channel is used to trace the 2D cell adhesion boundary and compute adhesion area and shape factor, S. The scale bar corresponds to 10 μm. (b) Histograms of cell volumes on 3-kPa, 12.6-kPa, and glass substrates for 3T3, NuFF, and MSCs. The wide distribution reflects intrinsic variation in cell size as well as effects due to cell cycle variation. The distributions skew to the left, reflecting that there are more young than old cells. (c–e) The average cell volumes for 3 kPa, 12.6 kPa, glass (GPa), serum starvation, and aphidicolin treatment for 3T3 (c), MSCs (d), and NuFFs (e). At 12.6 kPa, 3T3s and MSCs are larger, while NuFFs are smaller. Serum starvation generally decreases cell volume while aphidicolin treatment generally increases cell volume. The average cell adhesion area and adhesion shape are also shown. The shape factor is defined as  . Distributions of adhesion areas and shapes are shown in Supplemental Figure S2. MSCs show the largest adhesion area at 12.6 kPa, but for NuFFs and 3T3s, the largest adhesion area occurs on glass substrates. (Scale bar = 10 μm; all error bars represent standard error. Statistical significance: *** p < 10–6; ** p < 0.001; * p < 0.01; n.s.: p > 0.05. Number of cells: for 3T3s: N = 66 on 3 kPa, N = 110 on 12.6 kPa, and N = 364 on collagen-coated glass; for MSCs: N = 142 on 3 kPa, N = 120 on 12.6 kPa, and N = 378 on collagen-coated glass; for NuFFs: N = 103 on 3 kPa, N = 140 on 12.6 kPa, and N = 160 on collagen-coated glass.)

. Distributions of adhesion areas and shapes are shown in Supplemental Figure S2. MSCs show the largest adhesion area at 12.6 kPa, but for NuFFs and 3T3s, the largest adhesion area occurs on glass substrates. (Scale bar = 10 μm; all error bars represent standard error. Statistical significance: *** p < 10–6; ** p < 0.001; * p < 0.01; n.s.: p > 0.05. Number of cells: for 3T3s: N = 66 on 3 kPa, N = 110 on 12.6 kPa, and N = 364 on collagen-coated glass; for MSCs: N = 142 on 3 kPa, N = 120 on 12.6 kPa, and N = 378 on collagen-coated glass; for NuFFs: N = 103 on 3 kPa, N = 140 on 12.6 kPa, and N = 160 on collagen-coated glass.)

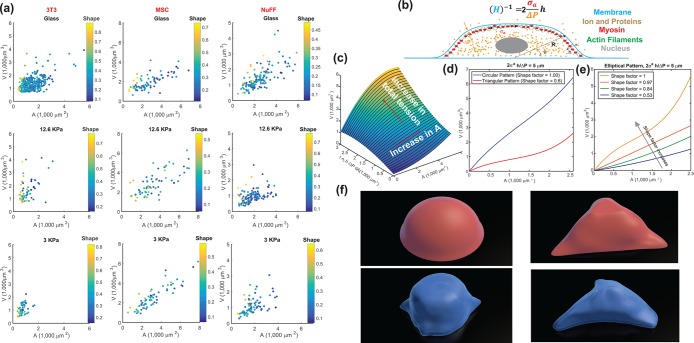

Cell two-dimensional (2D) adhesion area is often used as a proxy for cell volume. Because we simultaneously measure cell area, cell shape, and cell volume, we can examine the correlation between cell area and volume. Indeed, under all conditions, the cell area is positively correlated with the cell volume (Figure 2a); however, the slope of the area–volume correlation varies among different conditions. Moreover, the area–volume correlation depends on the 2D adhesion shape factor, defined as  . Cells with circular adhesions (S ∼ 1) are consistently larger in volume for a given area (Figure 2, a and c), although there is significant noise. While cells with small adhesion areas do tend to have smaller volumes, adhesion area does not uniquely determine cell volume. For example, NuFFs generally have a larger spread area than 3T3s, but they have similar volumes. Supplemental Figure S2 also shows additional data for serum starvation and aphidicolin conditions, displaying volume distributions as well as cell area versus volume, and cell area distributions for all conditions.

. Cells with circular adhesions (S ∼ 1) are consistently larger in volume for a given area (Figure 2, a and c), although there is significant noise. While cells with small adhesion areas do tend to have smaller volumes, adhesion area does not uniquely determine cell volume. For example, NuFFs generally have a larger spread area than 3T3s, but they have similar volumes. Supplemental Figure S2 also shows additional data for serum starvation and aphidicolin conditions, displaying volume distributions as well as cell area versus volume, and cell area distributions for all conditions.

FIGURE 2:

Cell volume in relation to cell adhesion area and cell shape. (a) Cell volume vs. cell adhesion area for 3T3s, MSCs, and NuFFs on different substrates. Each point is a single cell, color-coded by the shape factor, S. In all cases, area is correlated with volume, but the data are heterogeneous. Moreover, the slope of the correlation depends on the substrate stiffness. For the same area, more circular cells have a larger volume. Variations in cell shape and levels of contractility contribute to the observed variation. (b) Cartoon of an adherent cell. The volume is defined by the apical surface (specified at all points by R, the vector between the center of the adhesion area and the surface, and θ, the angle made by the vector R and the adhesion plane). Owing to pressure difference across the membrane, ΔP, the cell uses active myosin contraction,  , in the apical surface to balance the pressure difference. The mean curvature, H, is related to the apical surface shape R (see the Supplemental Material for more details), and h is the cortical thickness. (c) Model predictions of the cell volume as a function of total apical myosin and adhesion area. The model predicts that the cell volume increases with increasing adhesion area and total active myosin contraction. This figure assumes circular adhesion areas for the predicted volume. (d) Relationship between volume and area is dependent on adhesion shape. (e) Shape dependency on elliptical pattern illustrates that for the same

, in the apical surface to balance the pressure difference. The mean curvature, H, is related to the apical surface shape R (see the Supplemental Material for more details), and h is the cortical thickness. (c) Model predictions of the cell volume as a function of total apical myosin and adhesion area. The model predicts that the cell volume increases with increasing adhesion area and total active myosin contraction. This figure assumes circular adhesion areas for the predicted volume. (d) Relationship between volume and area is dependent on adhesion shape. (e) Shape dependency on elliptical pattern illustrates that for the same  , more circular cells are larger in size. This is consistent with data in a. All figures (c, d, and e) assume spatially homogeneous

, more circular cells are larger in size. This is consistent with data in a. All figures (c, d, and e) assume spatially homogeneous  . (f) Representative 3D cell shapes reconstructed from confocal z-stack images (blue) are compared with model cell shapes (red) computed for the same adhesion shape.

. (f) Representative 3D cell shapes reconstructed from confocal z-stack images (blue) are compared with model cell shapes (red) computed for the same adhesion shape.

Cortical contractility and tension distribution can predict cell volume

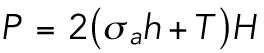

To further understand the connection between cell area and volume, we turn to a theoretical model of cell volume based on cell cortical-tension balance. When cells adhere to a flat substrate (Figure 2b), the cell volume is defined by the geometric shape of the apical cell surface. The cortex of mammalian cells consists of an actomyosin network that dynamically adjusts to the hydrostatic pressure difference between the inside and outside of the cell (Tao and Sun, 2015; Tao et al., 2017). The hydrostatic pressure difference, ΔP, arises from the slight osmotic imbalance between the cytoplasm and the extracellular medium. The pressure difference is balanced by the fluidized actomyosin cortex (Tao and Sun, 2015; Tao et al., 2017),

|

(1) |

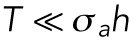

where  is the mechanical stress in the cortex, representing mostly myosin activity; h is the cortical thickness; T is the membrane tension; and H is the mean curvature of the cell surface. For a given pressure difference, cells can actively adjust cortical tension by activating different amounts of myosin contraction through the Rho signaling pathway (Krokan et al., 1981; Zhao et al., 2007; He et al., 2018). In most situations,

is the mechanical stress in the cortex, representing mostly myosin activity; h is the cortical thickness; T is the membrane tension; and H is the mean curvature of the cell surface. For a given pressure difference, cells can actively adjust cortical tension by activating different amounts of myosin contraction through the Rho signaling pathway (Krokan et al., 1981; Zhao et al., 2007; He et al., 2018). In most situations,  , and the relationship is simplified to

, and the relationship is simplified to

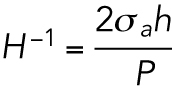

|

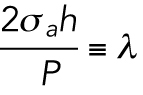

where

has dimensions of length. H is a geometric property of the cell and is related to the apical cell shape

has dimensions of length. H is a geometric property of the cell and is related to the apical cell shape  (Figure 2b and Supplemenntal Figure S3). Equation 1 is consistent with single cell measurements of cortical myosin distribution in Elliott et al. (2015). If the cell adhesion size, shape, and λ are known, then the volume of the cell can be computed (Supplemental Material and Supplemental Figure S3). Theoretical results predict that for the same level of λ, the volume is a monotonically increasing function of the adhesion area (Figure 2, c and d). Moreover, for the same adhesion area, increasing λ also increases cell volume. The slope of the area–volume curve also depends on S: for the same λ, an elongated cell has a smaller volume (Figure 2, d and e). The data show that rounder cells (S > 0.5) are indeed larger than more elongated cells (S < 0.5) for the same adhesion area (Figure 2a). The model can be implemented for arbitrary adhesion shapes, and the computed three-dimensional (3D) cell shapes can be compared with reconstructed 3D shapes of cells obtained from confocal z-stack images (Figure 2f).

(Figure 2b and Supplemenntal Figure S3). Equation 1 is consistent with single cell measurements of cortical myosin distribution in Elliott et al. (2015). If the cell adhesion size, shape, and λ are known, then the volume of the cell can be computed (Supplemental Material and Supplemental Figure S3). Theoretical results predict that for the same level of λ, the volume is a monotonically increasing function of the adhesion area (Figure 2, c and d). Moreover, for the same adhesion area, increasing λ also increases cell volume. The slope of the area–volume curve also depends on S: for the same λ, an elongated cell has a smaller volume (Figure 2, d and e). The data show that rounder cells (S > 0.5) are indeed larger than more elongated cells (S < 0.5) for the same adhesion area (Figure 2a). The model can be implemented for arbitrary adhesion shapes, and the computed three-dimensional (3D) cell shapes can be compared with reconstructed 3D shapes of cells obtained from confocal z-stack images (Figure 2f).

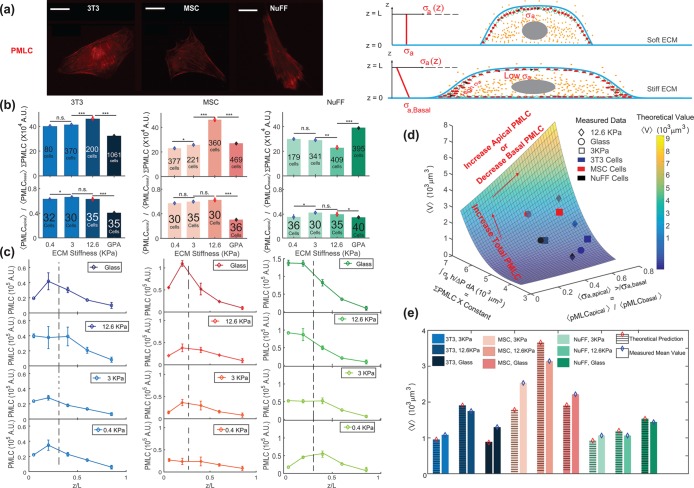

In live cells, we expect cortical tension and λ to vary spatially across the cell cortex, as seen, for example, in Elliott et al. (2015). The spatial distribution of λ impacts the cell volume. From our mathematical model, if λ is concentrated near the basal surface of the cell, then the cell volume is smaller (Supplemental Figure S3). If λ is uniformly distributed in the apical cell surface, then the volume is larger (Supplemental Figure S3). To obtain insights from data, we used immunofluorescence and imaged the distribution of phosphorylated myosin light chain (pMLC) using confocal z-stacks. The level of pMLC is a measure of active myosin assemblies in the cell and is a direct measure of  . We also expect pMLC to reflect the level of λ, since ΔP is likely to be spatially uniform and is governed by cell osmotic control. Figure 3 shows the measured vertical distribution of pMLC from confocal measurements for all stiffness conditions. On the average, pMLC is more concentrated near the basal surface on stiffer substrates, and more uniformly distributed across the apical cell surface on softer substrates (Figure 3, b and c), in accordance with previous measurements (Han et al., 2012). This trend is reflected by the apical versus basal pMLC ratio,

. We also expect pMLC to reflect the level of λ, since ΔP is likely to be spatially uniform and is governed by cell osmotic control. Figure 3 shows the measured vertical distribution of pMLC from confocal measurements for all stiffness conditions. On the average, pMLC is more concentrated near the basal surface on stiffer substrates, and more uniformly distributed across the apical cell surface on softer substrates (Figure 3, b and c), in accordance with previous measurements (Han et al., 2012). This trend is reflected by the apical versus basal pMLC ratio,  , where

, where  is defined as mean intensity above the dotted line in Figure 3c and

is defined as mean intensity above the dotted line in Figure 3c and  is defined as the mean intensity below the dotted line (Figure 3c). The dotted line separates the basal layer of the cell from the apical region and is defined as the z-position 1 μm above the z-position that displays basal stress fibers. Cells distribute pMLC differently on different substrates, mostly due to integrin engagement and focal adhesion formation (Geiger et al., 2009). It is known that integrins and focal adhesions nucleate actomyosin bundles in stress fibers (Tojkander et al., 2012). Our mechanical model predicts that the cell volume generally increases with increasing

is defined as the mean intensity below the dotted line (Figure 3c). The dotted line separates the basal layer of the cell from the apical region and is defined as the z-position 1 μm above the z-position that displays basal stress fibers. Cells distribute pMLC differently on different substrates, mostly due to integrin engagement and focal adhesion formation (Geiger et al., 2009). It is known that integrins and focal adhesions nucleate actomyosin bundles in stress fibers (Tojkander et al., 2012). Our mechanical model predicts that the cell volume generally increases with increasing  (Figure 3d). This is because greater pMLCapical corresponds to a more hemispherical cell with a greater mean height. Indeed, we can fully explain all average cell volume data under all conditions across three different cell types by measuring the total level of pMLC (measured from epifluorescence) and the pMLC distribution (reported by the apical-to-basal ratio) (Figure 3d). To connect measured pMLC intensities with λ, a single fitting parameter is used for each cell type (Supplemental Material and Figure 3e). Moreover, treating cells with the ROCK inhibitor Y27632 decreases the overall pMLC level observed in all three cell types, and we observe a corresponding decrease in cell volume (Supplemental Figure S5). For cells with the same adhesion area, cells exposed to Y27632 showed consistently smaller cell volumes. Therefore, cortical tension and tension distribution can predict cell volume, based on the cortical force–balance condition.

(Figure 3d). This is because greater pMLCapical corresponds to a more hemispherical cell with a greater mean height. Indeed, we can fully explain all average cell volume data under all conditions across three different cell types by measuring the total level of pMLC (measured from epifluorescence) and the pMLC distribution (reported by the apical-to-basal ratio) (Figure 3d). To connect measured pMLC intensities with λ, a single fitting parameter is used for each cell type (Supplemental Material and Figure 3e). Moreover, treating cells with the ROCK inhibitor Y27632 decreases the overall pMLC level observed in all three cell types, and we observe a corresponding decrease in cell volume (Supplemental Figure S5). For cells with the same adhesion area, cells exposed to Y27632 showed consistently smaller cell volumes. Therefore, cortical tension and tension distribution can predict cell volume, based on the cortical force–balance condition.

FIGURE 3:

Total level and spatial distribution of pMLC are predictors of cell volume. (a) Immunofluorescence widefield images of pMLC for 3T3, NUFF, and MSCs are used for the quantification of total pMLC in each cell. Confocal z-stack images are also taken at 1-μm z-steps to measure the relative amount of pMLC at each z-position. For stiffer substrates and relatively flat cells, there is typically higher concentration of pMLC near the basal surface. For rounder cells, the apical pMLC distribution is more uniform. (b) The average total pMLC (ΣpMLC) and relative ratio of apical vs. basal pMLC (<PMLCapical>/<PMLCbasal>) on different substrates. The relative levels of pMLC are also plotted as a function of z-position for all three cell lines. We observe that the distribution of pMLC varies with substrate stiffness as well as cell type. (c) The spatial distribution (along the z-axis) of mean pMLC intensity of three cell lines for different ECM stiffness. In general, mean pMLC intensity is higher at the cell basal area; but as the ECM becomes softer, the difference between apical and basal pMLC decreases. The dotted line marks the approximate division between basal and apical (defined as 1 μm above the z-position displaying basal stress fibers). (d) Computed cell volume as a function of total pMLC and the relative pMLC distribution. Each averaged volume in the surface was calculated for the total pMLC and relative pMLC in a range of areas within the experimental range. For each cell type the volume is scaled with respect to the cell volume on glass, and a single fitting parameter is used to relate total pMLC with integrated λ,  (Supplemental Material). (e) The model predictions for volume across all stiffnesses are explicitly compared. (Scale bar = 10 μm. All error bars represent standard error. Statistical significance: ***p < 10–6; **p < 0.001; *p < 0.05; n.s.: p > 0.05. Number of cells for epifluorescence imaging: for 3T3s: N = 80 on 0.4 kPa, N = 370 on 3 kPa, N = 200 on 12.6 kPa, and N = 1061 on collagen-coated glass; for MSCs: N = 377 on 0.4 kPa, N = 221 on 3 kPa, N = 360 on 12.6 kPa, and N = 469 on collagen-coated glass; for NuFFs: N = 179 on 0.4 kPa, N = 341 on 3 kPa, N = 409 on 12.6 kPa, and N = 395 on collagen-coated glass. Number of cells for confocal microscopy: for 3T3s: N = 32 on 0.4 kPa, N = 30 on 3 kPa, and N = 35 on 12.6 kPa and on collagen-coated glass; for MSCs: N = 30 on 0.4 kPa and on 12.6 kPa, N = 35 on 3 kPa, and N = 36 on collagen-coated glass; for NuFFs: N = 36 on 0.4 kPa, N = 30 on 3 kPa, N = 35 on 12.6 kPa, and N = 40 on collagen-coated glass.)

(Supplemental Material). (e) The model predictions for volume across all stiffnesses are explicitly compared. (Scale bar = 10 μm. All error bars represent standard error. Statistical significance: ***p < 10–6; **p < 0.001; *p < 0.05; n.s.: p > 0.05. Number of cells for epifluorescence imaging: for 3T3s: N = 80 on 0.4 kPa, N = 370 on 3 kPa, N = 200 on 12.6 kPa, and N = 1061 on collagen-coated glass; for MSCs: N = 377 on 0.4 kPa, N = 221 on 3 kPa, N = 360 on 12.6 kPa, and N = 469 on collagen-coated glass; for NuFFs: N = 179 on 0.4 kPa, N = 341 on 3 kPa, N = 409 on 12.6 kPa, and N = 395 on collagen-coated glass. Number of cells for confocal microscopy: for 3T3s: N = 32 on 0.4 kPa, N = 30 on 3 kPa, and N = 35 on 12.6 kPa and on collagen-coated glass; for MSCs: N = 30 on 0.4 kPa and on 12.6 kPa, N = 35 on 3 kPa, and N = 36 on collagen-coated glass; for NuFFs: N = 36 on 0.4 kPa, N = 30 on 3 kPa, N = 35 on 12.6 kPa, and N = 40 on collagen-coated glass.)

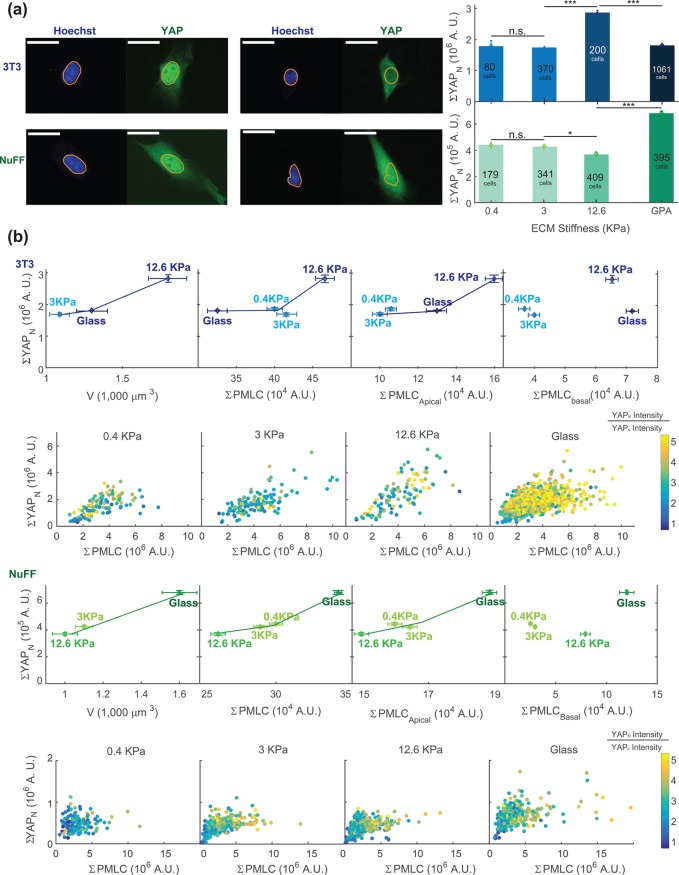

Cell tension, growth, and connections to the Hippo signaling pathway

We have shown that cell cortical tension and the spatial distribution of pMLC can explain observed cell volumes on different substrates. However, it is not clear how the cell regulates growth and volume increase over the cell cycle and determine the cell volume at division. One possibility is that as cortical tension adjusts to increasing cell mass, the mechanical cue from increasing cortical tension can be a signal for regulating cell growth and division. YAP and its paralogue TAZ are downstream effectors of the Hippo pathway and have been shown to respond to the stiffness of the substrate (Dupont et al., 2011). To examine the relationship between cell tension as measured by pMLC and YAP/TAZ, we performed quantitative immunofluorescence measurements, stained YAP/TAZ, pMLC, and DNA for all three cell types under all conditions, and quantified single-cell YAP/TAZ and pMLC levels using widefield epifluorescence (Figure 4). The antibody used stained for both YAP and TAZ, and therefore, from here on, YAP refers to both YAP and TAZ. Qualitatively, NuFFs and 3T3s show predominantly nuclear localization of YAP (Supplemental Figure S6g) under all conditions; however, the total amount of nuclear YAP, denoted as ΣYAPn, did show a significant correlation with the average cell volume under all conditions (Figure 4b). The mean cytoplasmic YAP intensity was not observed to vary significantly between conditions, though there was considerable cell–cell heterogeneity. For this reason, we did not find the YAP nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio to be a useful measure of activity in these cell lines. Note that the cell volume as a function of the substrate stiffness shows opposing trends in NuFFs and 3T3s. Cells have highest volume on 12.6 kPa for 3T3s, but lowest volume on 12.6 kPa for NuFFs. Nevertheless, for both cell types, higher cell volume corresponds to higher levels of nuclear YAP. Both cell types show the highest cell volume and the highest level of nuclear YAP with aphidicolin treatment (Supplemental Figure S8, g–i).

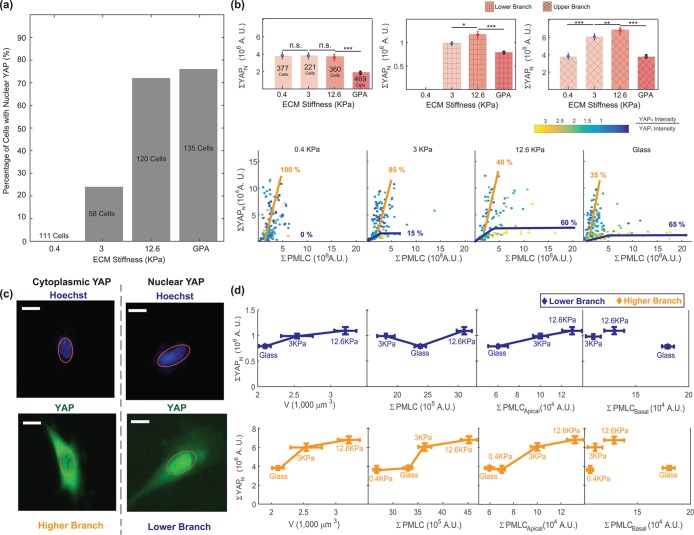

FIGURE 4:

Cell volume is correlated with nuclear YAP/TAZ level in 3T3s and NuFFs. (a) Immunofluorescence widefield images with YAP in green and DNA in blue. The DNA channel is used to mask the nuclear region. The total nuclear YAP (ΣYAPN) is obtained from epifluorescence images for different stiffnesses. (b) The total average nuclear YAP is plotted vs. the average measured cell volume, average total pMLC level, and apical and basal pMLC levels. The individual cell data are also plotted in panels below and color-coded by the nuclear YAP intensity/cytoplasmic YAP intensity ratio. At both the single-cell and ensemble levels, higher nuclear YAP is correlated with higher total pMLC. Higher nuclear YAP is also correlated with larger cell volume and higher apical pMLC, even though NuFFs and 3T3s display opposing trends as functions of substrate stiffness. Nuclear YAP is not correlated with basal pMLC. For NuFFs, nuclear YAP seems to plateau at large ΣpMLC, suggesting that nuclear YAP level reaches a maximum even as pMLC level is increasing. This suggests that there is another signal limiting nuclear YAP levels in NuFFs. Note that in both 3T3s and NuFFs, the nuclear-to-cytoplasmic YAP concentration ratios are generally higher than 1. Visually, nearly all cells appear to have significant nuclear YAP. (Scale bar = 10 μm. All error bars represent standard error. Statistical significance: ***p < 10–6; *p < 0.01; n.s.: p > 0.05. Number of cells for epifluorescence imaging: for 3T3s: N = 80 on 0.4 kPa, N = 370 on 3 kPa, N = 200 on 12.6 kPa, and N = 1061 on collagen-coated glass; for NuFFs: N = 179 on 0.4 kPa, N = 341 on 3 kPa, N = 409 on 12.6 kPa, and N = 395 on collagen-coated glass.)

Moreover, the total level of pMLC is correlated with total nuclear YAP, both at the individual cell level (Figure 4, a and b) and at the population average level across all conditions (Figure 4b). Here, 3T3s show a continuous rise in nuclear YAP level with increasing pMLC, but the nuclear YAP level saturates in NuFFs with increasing pMLC, suggesting that other factors may be at play in controlling nuclear YAP in NuFFs that are absent in the standard 3T3s.

From confocal images, it is possible to estimate the relative proportion of pMLC above the basal surface (apical surface) versus the pMLC in the basal surface of the cell (Figures 3, b and c, and 4b). Because it is the apical surface of the cell that determines the cell volume, we compute the total apical pMLC by summing apical intensities from Figure 3c. We observe that the level of apical pMLC is correlated with nuclear YAP for all conditions, whereas basal pMLC is not correlated with nuclear YAP (Figures 4b and 5d). These results directly implicate apical pMLC, and not total pMLC, as a possible signal for nuclear translocation of YAP. We speculate that this could be because apical and basal pMLC (associated with adhesions) may be biochemically distinct to serve different signaling functions in the cell.

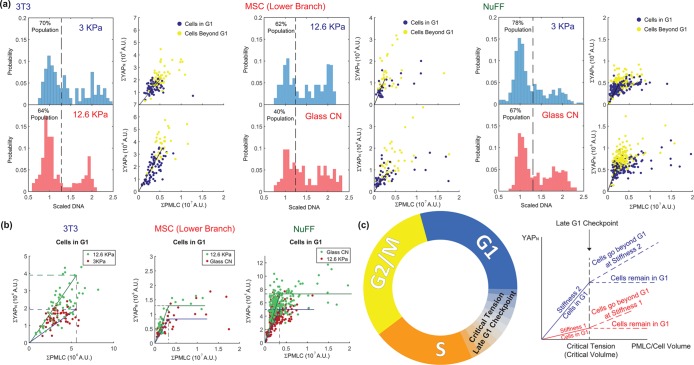

FIGURE 5:

MSCs show bifurcated behavior in YAP nuclear localization and pMLC level. (a) Percentage of MSCs showing nuclear YAP localization. With increasing stiffness, more cells contain nuclear YAP, in agreement with Dupont et al. (2011). (b) The measured total amount of nuclear YAP, ΣYAPN, decreases with increasing stiffness. Closer examination of single-cell nuclear YAP and pMLC data shows bifurcated behavior on different substrates. On stiffer substrates there are two branches. The upper branch has high overall YAP expression, but low nuclear-to-cytoplasmic (N/C) YAP intensity ratio. The lower branch has lower overall YAP expression, but high N/C. The proportion of the upper branch cells decreases with increasing stiffness. Thus, on softer substrates, it appears that most cells have a lower N/C YAP ratio. On stiffer substrates, there are more cells with high nuclear N/C YAP ratio. (c) Representative images of MSCs with nuclear YAP localization and cytoplasmic YAP localization. (d) When the total nuclear YAP is plotted vs. volume, pMLC, and apical pMLC, the positive correlation between nuclear YAP and these variables is recovered, similarly to 3T3s and NuFFs. Cells in these separate branches are both positive for MSC markers CD90 and CD105 (Supplemental Figure S7). These results suggest that these are two branches that may not be distinguished by typical MSC differentiation markers. (All error bars represent standard error. Statistical significance: ***p < 10–6; **p < 0.001; *p < 0.01; n.s.: p > 0.05. Number of cells: N = 377 on 0.4 kPa, N = 221 on 3 kPa, N = 360 on 12.6 kPa, and N = 469 on collagen-coated glass.)

MSCs show bifurcated cell tension dependence

In fully differentiated cells, we observed that apical pMLC is correlated with the level of nuclear YAP. Under conditions where cell volume is higher, the average nuclear YAP level is also higher. When we examine the same type of data for MSCs, these relationships no longer hold (Figure 5). While on the average the cell volume is correlated with nuclear YAP, nuclear YAP is no longer positively correlated with pMLC or apical pMLC. When we examine single-cell data, we discover that depending on the stiffness of the substrate, the correlation between total nuclear YAP and pMLC bifurcates, showing two distinct branches. As substrate stiffness increases, there appear to be more cells in the lower branch with lower nuclear YAP. The upper branch generally contains cells with lower nuclear-to-cytoplasmic YAP–intensity (N/C) ratio and higher overall YAP expression. The lower branch contains cells with higher N/C ratio, but lower overall YAP as well as lower nuclear YAP (Figure 5, b and c). The relative proportion of cells in the upper branch decreases with increasing stiffness, which is consistent with the results of Dupont et al. (2011). Interestingly, only a single branch is observed in the cell area versus volume correlation (Figure 2a). We hypothesize that the two branches in the nuclear YAP/pMLC correlation represent two phenotypes of MSCs, although more than 99% of our MSC population stained positively for both stem markers: CD90 and CD105 (Supplemental Figure S7). Clearly, these cells are not distinguishable through the use of these common differentiation markers. Stem cells might be sensitive to their neighboring cell identity (Smith et al., 2015) and cell density; it is possible that cell phenotype is influenced by the local environment.

To check whether cell tension and YAP relationships still hold for the observed branches, we examined the nuclear YAP and pMLC correlations for the separate branches, while assuming that their average cell volumes are similar. We included only cells that are distinct in either branch, and exclude cells that have low nuclear YAP and low pMLC near the origin. The upper/lower branch is defined by cells with ΣYAPn higher/lower than the plateau drawn in Figure 5b. We find that for individual branches, the correlations between ΣYAPn, cell volume, and apical pMLC are again preserved (Figure 5d).

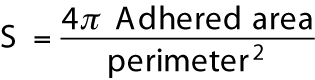

If YAP plays a role in cell cycle and growth regulation, then the level of myosin can potentially influence YAP phosphorylation and allow the cell to sense its own size. Indeed, our data are suggestive of a size checkpoint between G1 and S that is determined by cell tension. Figure 6 shows the same nuclear YAP and pMLC correlation, but now labeled by cell DNA content. Nuclear YAP level rises with increasing pMLC at different rates on different-stiffness substrates, but the maximal YAPn is reached at the same level of pMLC (Figure 6). However, there is diversity in this behavior. For 3T3s, nuclear YAP seems to continue to increase in S/G2 together with pMLC and the rate of YAPn increase depends on the substrate. In NuFFs, YAPn still increases with pMLC in G1 and stops rising at the same level of pMLC, but there are some cells in G1 with high pMLC at the level of the YAPn plateau. The plateau value varies with substrate stiffness. The G1 cells with high pMLC are likely very high in volume. For MSCs in the lower branch, the behavior is similar to that of NuFFs, showing a stiffness-dependent YAPn plateau. MSCs in the upper branch are entirely different. They have high YAP expression, but no obvious checkpoint based on tension between G1 and S or distinguishing YAP levels between G1 and S. Recent work on confluent epithelial cells also suggests that cell tension influences the cell cycle (Uroz et al., 2018), consistent with the tension checkpoint idea presented here.

FIGURE 6:

Nuclear YAP and pMLC relation suggests a late G1 checkpoint based on cell tension. (a) Two stiffness conditions with the greatest difference in average cell volume are selected for 3T3s, MSCs, and NuFFs. The DNA histogram (left) is shown together with the total nuclear YAP vs. the total cell pMLC level (right). Cells are colored by their DNA content, with G1 cells identified as cells with DNA content below the dashed line in the DNA histogram (1.25 in the scaled DNA level). Cells beyond G1 have higher levels of nuclear YAP and pMLC. The rate of nuclear YAP and pMLC increase, however, varies with condition and cell type. (b). When cells in G1 under different conditions are compared, we observe that nuclear YAP rises with pMLC in G1 until a critical pMLC level is reached, suggesting a checkpoint based on cell tension. For 3T3s, cells proceed to S after the critical level of pMLC and nuclear YAP continues to rise with pMLC. For NuFFs and the MSC lower-branch populations, cells in G1 can continue to increase in pMLC and cell size, but the nuclear YAP level plateaus after the critical level of pMLC. (c) G1–S transition checkpoint based on cell tension. Nuclear YAP increases with increasing pMLC until a common critical tension level is reached, at which the cell transitions from G1 to S. If cells continue to grow in G1, nuclear YAP does not increase after the critical tension, but plateaus. These cells are presumably arrested in G1.

DISCUSSION

Cell volume is a fundamental property of living cells, and understanding how cells control their growth and volume has implications for development and wound healing as well as a variety of diseases. By performing quantitative immunofluorescence and single-cell volume measurements, we discovered that cell volume depends on cell adhesion area and substrate stiffness. This dependence may be explained by how cells balance forces at the cell surfaces. At an upstream level, cells can sense mechanical force changes in the cell membrane through tension-sensitive ion channels and the Rho pathway. When the cytoplasmic pressure, ΔP, increases (e.g., from import of organic molecules and ions to make more proteins), the cell also increases water content and increasingly activates RhoA and myosin contraction as more proteins are synthesized through the cell cycle. As a result of this regulatory system, as the cell grows, more active myosin is developed in the cortex. The spatial distribution of myosin depends on additional factors such as integrin engagement and substrate stiffness, but the overall active myosin content must increase with increasing cell size. We find that the level of apical myosin, or myosin not engaged with integrin adhesions and stress fibers, is directly related to the nuclear YAP level, which also explains why β-integrin influences YAP nuclear localization (Elosegui-Artola et al., 2016).

In addition to the proposed mechanism of a tension-based cell cycle checkpoint, we find that cell volume under different conditions can be explained quantitatively from a theoretical model of 3D cell shape. We also discover that synchronization using serum starvation and aphidicolin have opposite effects on cell volume. The heterogeneous distribution of cell volume can be understood by considering the distribution of cells through the cell cycle. The cell cycle distribution is not uniform, but concentrated near younger cells. Because expression levels of many proteins depend on the cell cycle, this result suggests that cell cycle–averaged expression-level changes would depend heavily on the relative duration of each cell cycle phase (Wang et al., 2018). Any perturbations that influence the cell cycle would indirectly influence the expression of many types of proteins. The YAP and the Hippo pathways have been proposed to influence the cell cycle (Shen and Stanger, 2015). Quantitative single-cell measurement would reveal how mechanical tension and the Hippo pathway can regulate cell growth and proliferation in a variety of conditions.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The present work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01GM114675 and U54CA210172. We thank Gehua Zhen for helping with isolation of MSC cells. We also acknowledge Martin Rietveld for helping with preparation of the figures.

Abbreviations used:

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- PDMS

polydimethylsiloxane

- pMLC

phosphorylated myosin light chain

- ROCK

Rho-associated protein kinase

- TAZ

transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif, also known as WWTR1

- YAP

Yes-associated protein

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBoC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E18-04-0213) on August 16, 2018.

REFERENCES

- Bottier C, Gabella C, Vianay B, Buscemi L, Sbalzarini IF, Meiser J-J, Verkhovsky AB. (2011). Dynamic measurement of the height and volume of migrating cells by a novel fluorescence microscopy technique. Lab Chip , 2855–3863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks RF, Shields R. (1985). Cell growth, cell division and cell size homeostasis in Swiss 3T3 cells. Exp Cell Res , 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadart C, Zlotek-Zlotkiewicz E, Venkova L, Thouvenin O, Racine V, Le Berre M, Monnier S, Piel M. (2017). Fluorescence eXclusion measurement of volume in live cells. Methods Cell Biol , 103–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Codelia VA, Sun G, Irvine KD. (2014). Regulation of YAP by mechanical strain through Jnk and Hippo signaling. Curr Biol , 2012–2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conlon I, Raff M. (2003). Differences in the way a mammalian cell and yeast cells coordinate cell growth and cell-cycle progression. J Biol , 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong J, Feldmann G, Huang J, Wu S, Zhang N, Comerford SA, Gayyed MF, Anders RA, Maitra A, Pan D. (2007). Elucidation of a universal size-control mechanism in Drosophila and mammals. Cell , 1120–1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont S, Morsut L, Aragona M, Enzo E, Giulitti S, Cordenonsi M, Zanconato F, Le Digabel J, Forcato M, Bicciato S, et al. (2011). Role of YAP/TAZ in mechanotransduction. Nature , 179–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott H, Fischer RS, Myers KA, Desai RA, Gao L, Chen CS, Adelstein RS, Waterman CM, Danuser G. (2015). Myosin II controls cellular branching morphogenesis and migration in three dimensions by minimizing cell surface curvature. Nat Cell Biol , 137–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elosegui-Artola A, Oria R, Chen Y, Kosmalska A, Perez-Gonzalez C, Castro N, Zhu C, Trepat X, Roca-Cusachs P. (2016). Mechanical regulation of a molecular clutch defines force transmission and transduction in response to matrix rigidity. Nat Cell Biol , 540–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engler AJ, Sen S, Sweeney HL, Discher D. (2006). Matrix elasticity directs stem cell lineage specification. Cell , 677–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Gonzalez R, Zallen JA. (2009). Cell mechanics and feedback regulation of actomyosin networks. Sci Signal , pe78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox TO, Pardee AB. (1970). Animal cells: noncorrelation of length of G1 phase with size after mitosis. Science , 80–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger B, Spatz JP, Bershadsky AD. (2009). Environmental sensing through focal adhesions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol , 21–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginzberg MB, Kafri R, Kirschner M. (2015). On being the right (cell) size. Science , 1245075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godin M, Delgado FF, Son S, Grover WH, Bryan AK, Tzur A, Jorgensen P, Payer K, Grossman AD, Kirschner MW, Manalis SR. (2010). Using buoyant mass to measure the growth of single cells. Nat Methods , 387–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo M, Pegoraro AF, Mao A, Zhou EH, Arany PR, Han Y, Mackintosh FC. (2017). Cell volume change through water efflux impacts cell stiffness and stem cell fate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA , E8618–E8627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han SJ, Bielawski KS, Ting LH, Rodriguez ML, Sniadecki NJ. (2012). Decoupling substrate stiffness, spread area, micropost density: a close spatial relationship between traction forces and focal adhesions. Biophys J , 640–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L, Tao J, Maity D, Si F, Wu Y, Wu T, Sun SX. (2018). Role of membrane-tension gated Ca flux in cell mechanosensation. J Cell Sci jcs-208470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hola M, Riley PA. (1987). The relative significance of growth rate and interdivision time in the size control of cultured mammalian epithelial cells. J Cell Sci , 73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley J. (1970). Sizing particles with a Coulter counter. Biophys J , 74–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killander D, Zetterberg A. (1965). A quantitative cytochemical investigation of the relationship between cell mass and initiation of DNA synthesis in mouse fibroblasts in vitro. Exp Cell Res , 12–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krokan H, Wist E, Krokan RH. (1981). Aphidicolin inhibits DNA synthesis by DNA polymerase alpha and isolated nuclei by a similar mechanism. Nucleic Acids Res , 4709–4710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd AC. (2013). The regulation of cell size. Cell , 1194–1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low BC, Pan CQ, Shivashankar GV, Bershadsky A, Sudol M, Sheetz M. (2014). YAP/TAZ as mechanosensors and mechanotransducers in regulating organ size and tumor growth. FEBS Lett , 2663–2670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccolo S, Dupont S, Cordenonsi M. (2014). The biology of YAP/TAZ: Hippo signaling and beyond. Physiol Rev , 1287–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehfeldt F, Brown AEX, Raab M, Cai S, Zajac AL, Zemel A, Discher DE. (2012). Hyaluronic acid matrices show matrix stiffness in 2D and 3D dictates cytoskeletal order and myosin-II phosphorylation within stem cells. Integ Biol , 422–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saucedo LJ, Edgar BA. (2007). Filling out the Hippo pathway. Nat Mol Cell Biol , 613–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmelzle T, Hall MN. (2000). TOR, a central controller of cell growth. Cell , 253–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Z, Stanger BZ. (2015). YAP regulates S-phase entry in endothelial cells. PLoS One , e0117522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith Q, Stukalin E, Kusuma S, Gerecht S, Sun SX. (2015). Stochasticity and spatial interaction govern stem cell differentiation dynamics. Sci Rep , 12617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son S, Kang JH, Oh S, Kirschner MW, Mitchison TJ, Manalis S. (2015). Resonant microchannel volume and mass measurements show that suspended cells swell during mitosis. J Cell Biol , 757–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son S, Tzur A, Weng Y, Jorgensen P, Kim J, Kirschner MW, Manalis SR. (2012). Direct observation of mammalian cell growth and size regulation. Nat Methods , 910–912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stukalin EB, Aifuwa I, Kim JS, Wirtz D, Sun SX. (2013). Age-dependent stochastic models for understanding population fluctuations in continuously cultured cells. J R Soc Interface , 20130325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung Y, Tzur A, Oh S, Choi W, Li V, Dasari RR, Yaqoob Z, Kirschner MW. (2013). Size homeostasis in adherent cells studied by synthetic phase microscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA , 16687–16692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao J, Li Y, Vig DK, Sun SX. (2017). Cell mechanics: a dialogue. Rep Prog Phys , 036601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao J, Sun SX. (2015). Active biochemical regulation of cell volume and a simple model of cell tension response. Biophys J , 1541–1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tojkander S, Gateva G, Lappalainen P. (2012). Actin stress fibers-assembly, dynamics and biological roles. J Cell Sci , 1855–1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzur A, Kafri R, LeBleu VS, Lahav G, Kirschner MW. (2009). Cell growth and size homeostasis in proliferating animal cells. Science , 167–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uroz M, Wistorf S, Serra-Picamal X, Conte V, Sales-Pardo M, Roca-Cusachs P, Guimera R, Trepat X. (2018). Regulation of cell cycle progression by cell–cell and cell–matrix forces. Nat Cell Biol , 646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varsano G, Wang Y, Wu M. (2017). Probing mammalian cell size homeostasis by channel-assisted cell shaping. Cell Rep , 397–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Chai N, Sha B, Guo M, Zhuang J, Xu F, Li F. (2018). The effect of substrate stiffness on cancer cell volume homeostasis. J Cell Physiol , 1414–1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen A, Fried J, Kitahara T, Stride A, Clarkson BD. (1975). The kinetic significance of cell size, I. Variation of cell cycle parameters with size measured at mitosis. Exp Cell Res , 295–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu FX, Zhao B, Guan KL. (2015). Hippo pathway in organ size control, tissue homeostasis and cancer. Cell , 811–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao B, Tumaneng K, Guan KL. (2011). The Hippo pathway in organ size control, tissue regeneration and stem cell self-renewal. Nat Cell Biol , 877–881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao B, Ye X, Yu J, Li L, Li W, Li S, Yu J, Lin JD, Wang CY, Chinnaiyan AM, et al. (2008). TEAD mediates YAP-dependent gene induction and growth control. Genes Dev , 1962–1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao XH, Laschinger C, Arora P, Szaszi K, Kapus A, McCulloch CA. (2007). Force activates smooth muscle a-actin promoter activity through the Rho signaling pathway. J Cell Sci , 1801–1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlotek-Zlotkiewicz E, Monnier S, Cappello G, Le Berre M, Piel M. (2015). Optical volume and mass measurements show that mammalian cells swell during mitosis. J Cell Biol , 765–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.