Abstract

Osteoporosis development is closely associated with oxidative stress and reactive oxygen species (ROS). Taurine has potential antioxidant effects, but its role in osteoblasts is not clearly understood. The aim of this study was to determine the protective effects and mechanisms of actions of taurine on hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)-induced oxidative stress in osteoblast cells. UMR-106 cells were treated with taurine prior to H2O2 exposure. After treatment, cell viability, apoptosis, intracellular ROS production, malondialdehyde content, and alkaline phosphate (ALP) activity were measured. We also investigated the protein levels of β-catenin, ERK, CHOP and NF-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) along with the mRNA levels of Nrf2 downstream antioxidants. The results showed that pretreatment of taurine could reverse the inhibition of cell viability and suppress the induced apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner: taurine significantly reduced H2O2-induced oxidative damage and expression of CHOP, while it induced protein expression of Nrf2 and β-catenin and activated ERK phosphorylation. DKK1, a Wnt/β-catenin signaling inhibitor, significantly suppressed the taurine-induced Nrf2 signaling pathway and increased CHOP. Activation of ERK signaling mediated by taurine in the presence of H2O2 was significantly inhibited by DKK1. These data demonstrated that taurine protects osteoblast cells against oxidative damage via Wnt/β-catenin-mediated activation of the ERK signaling pathway.

Keywords: Taurine, Oxidative stress, Antioxidants, Wnt/β-catenin, Osteoblast

INTRODUCTION

Osteoporosis results from an imbalance between bone resorption and bone formation. Osteoblast injury is considered the main cause of osteoporosis, as osteoblasts play an important role in bone development and reconstruction of the bone matrix (Wauquier et al., 2009). Oxidative stress results from the excessive generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) (Dai et al., 2017), and oxidative damage to osteoblasts is closely associated with the pathological progress of osteoporosis (Cervellati and Bergamini, 2016). Although both ROS and RNS induce oxidative stress, it is well known that ROS are the primary cause of oxidative damage (Bernardo, et al., 2015). ROS impair bone formation by enhancing lipid peroxidation, inhibiting antioxidants, and inducing apoptosis (Wauquier et al., 2009; Pisoschi and Pop, 2015); therefore, it is essential to suppress ROS by inducing antioxidants, which may contribute to bone formation and antagonize osteoporosis.

Taurine (2-aminoethanesulfonic acid) is widely distributed in animal tissues (Jang and Kim, 2013) and has a variety of functions, such as stabilizing the cell membrane, regulating osmosis and calcium transport, immunoregulation, neuroprotection, and regulating protein phosphorylation (Jang and Kim, 2013; Roman-Garcia et al., 2014) via its transporter (Zhang et al., 2011). It has been reported that taurine can inhibit oxidative stress by scavenging ROS and reducing lipid peroxidation (Higuchi et al., 2012). Despite the importance of taurine in regulating various biological functions, its exact effects, especially the molecular mechanisms that impact oxidative stress-induced osteoporosis, are still unknown.

Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways play crucial roles in bone formation by mediating responses to various extracellular stimuli (Greenblatt et al., 2010; Zou et al., 2011). The phosphorylation of extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK) is particularly important for osteoblast differentiation, as it regulates runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2) and ribosomal s6 kinase 2 (RSK2), which could modulate late-stage osteoblast synthesis (Zou et al., 2011; Koizumi et al., 2018). Matsushita et al. (2009) indicated that the deletion of ERK1 and ERK2 in mice led to a reduction in bone mineralization. Other notable studies have recently reported that ERK can decrease oxidative-stress-induced damage by regulating nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), which is a transcription factor that manages multiple antioxidants (Wong et al., 2016). Therefore, the investigation of a novel pathway involved in the regulation of ERK signaling is another major interest in osteoporosis research.

The Wnt/β-catenin pathway is a critical signaling pathway for osteoblast differentiation (Shim et al., 2013; Nusse and Clevers, 2017). Inhibition of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway leads to dysregulated osteoblast differentiation and alterations in bone formation (Kim et al., 2015). β-catenin is the major protein involved in Wnt/β-catenin signaling, and it forms a system with polyposis coli (APS), Axin, casein kinase 1 alpha 1 (CK1α), and glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) under the basal condition. While ligands of the Wnt pathway bind to the membrane receptor, lipoprotein receptor-related proteins 5 and 6 (LRP5 and LRP6, respectively), β-catenin can be released from the system and translocate into the nucleus, where it regulates transcription of the target genes, such as RUNX2 (Shim et al., 2013; Nusse and Clevers, 2017). Upregulated bone formation caused by the dysfunction of sclerostin (SOST), an inhibitor of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, further demonstrates that the Wnt/β-catenin pathway is important to the development of bone mass(Yee et al., 2018). Nevertheless, there is much to be explored regarding the mechanism of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in oxidative-stress-induced damage to osteoblasts.

To investigate the mechanism of taurine in oxidative-stress-induced cell apoptosis, H2O2 was used to establish an in-vitro experimental model of osteoblasts. ROS are a family of molecules, including reactive free-oxygen radicals (e.g., superoxide anion [O2−]), which have short lifespans, and stable non-radical oxidants (e.g., hydrogen peroxide [H2O2]), which have long biological lifespans and higher stability compared to free radicals (Abdal Dayem et al., 2017); therefore, H2O2 has been used extensively in the in-vitro induction of oxidative stress (Lin et al., 2015). In this study, H2O2-treated, osteoblast-like UMR-106 cells were used to determine whether taurine confers antioxidant defense and, if so, what is the mechanism involved.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Dulbecco’s modified essential medium (DMEM), penicillin-streptomycin (Pen/Strep), trypsin-EDTA, and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from Life Technologies (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY, USA). Taurine was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (T0625, St. Louis, MO, USA). The Wnt/β-catenin signaling inhibitor, DKK1 (5897-DK), was purchased from purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). All other reagents were purchased from commercial suppliers and of the highest purity available.

Cell culture and treatment

Rat osteogenic sarcoma line UMR-106 (ATCC CRL-1661) cells were grown to confluence in DMEM media with 10% FBS and 1% Pen/Strep at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Cells were treated with medium containing different concentrations of taurine (0, 10, 50, 100, and 200 mM) for 3 h before treatment with H2O2 (100 μM) for 24 h. DKK1 (100 ng/mL) was treated for 1 h before taurine treatment.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was measured using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide (MTT). The cells were initially seeded onto 96-well plates at a density of 5×104/well. Following the applied treatment, the MTT dye (20 μL per well, 5 mg/mL, Sigma Aldrich) was added to the supernatant and incubated at 37°C for 4 h. Afterwards, the media was removed and 150ul DMSO/well was added. Then, the plate was incubated at 37°C for further 15 min, and the optic density (OD) was measured at 570 nm.

Apoptosis quantification

Cell apoptosis was examined using a commercial ELISA kit with an anti-histone antibody and a secondary anti-DNA antibody, according to the instruction (Cell Death Detection ELISA, 11544675001, Roche, Shanghai, China). The OD was measured at 405 nm.

Oxidative stress assay

Intracellular ROS was measured using the cell permeant reagent 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFDA) (ab113851, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA). Briefly, after applying the treatment, DCFDA dye (5.0 μg/mL) was added to cells and fluorescence was read at the top of the plastic microplate at an excitation of 485 nm and an emission of 530 nm using a fluorescence microplate reader.

To monitor lipid peroxidation, TBARS analysis was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (700870, Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Absorbance was measured at 530 nm.

ALP activity assay

Induction of ALP is an unequivocal marker of bone cell differentiation. At the end of the treatment, ALP activity was measured using an ALP assay kit (ab83369, Abcam) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The absorbance of the samples was measured at 405 nm.

Western blotting

Cells were lysed in an appropriate volume of RIPA buffer. Then, the lysates were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C and the supernatants were used as the total cell lysates. About 30 μg of protein was separated on 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Each membrane was blocked with 0.1M Tris-buffered saline-0.1% Tween 20 (TBST) buffer containing 5% skim milk for 1h at RT. Then membranes were incubated with specific primary antibodies (1:2000) overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation with appropriate secondary antibodies for 1h at RT (1:2000). The protein signals were visualized using Supersignal West Pico Chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). A densitometry analysis was conducted using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). Total ERK (4696) and phosphor-ERK (4370) were purchased from CST (Cell signaling technology, Danvers, MA, USA); β-catenin (ab32572), Nrf2 (NF-E2-related factor 2, ab137550), CHOP (ab11419), GAPDH (ab8245) were purchased from Abcam; taurine transporter (TAUT) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (sc-393036, Dallas, TX, USA).

Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and 1.5 μg was reverse transcribed using SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen). The cDNA was amplified using 2X Power SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Real-time PCR, which involves denaturation at 95°C for 15 s and primer annealing at 59°C for 30 s for 40 cycles, was carried out. GAPDH was always tested as the internal control gene (Table 1). The 2−ΔΔCt method was utilized to calculate the relative expression of indicated mRNA. Its value was normalized to that of control cells.

Table 1.

Primers used for gene expression analysis

| Genesa | Sequences (5′–3′) |

|---|---|

| HO-1 | F: GCCTGCTAGCCTG GTTCAAG R: AGCGGTGTCTGGGATGAACTA |

| GCLC | F: GTCCTCAGGTGACATTCCAAGC R: TGTTCTTCAGGGGCTCCAGTC |

| NQO1 | F: GGCAGAAGAGCACTGATCGTA R: TGATGGGATTGAAGTTCATGGC |

| GAPDH | F: AAGCTGGTCTCAACGGGAAAC R: GAAGACGCCAGTAGACTCCACG |

HO-1, heme oxygenase-1; GCLC, glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit; NQO1, NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase-1.

Statistical analysis

All data analysis was completed using GraphPad PRISM 5.0 software (Graphpad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. The significance level of treatment effects was determined using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison tests between groups or paired t-test. Pearson correlation analysis was performed to determine the relationship between ALP activity and ROS generation. Values of p<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Effects of taurine on H2O2-induced cytotoxicity

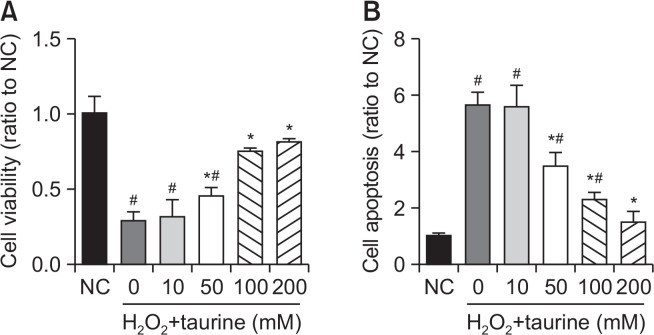

To assess the effects of taurine on osteoblasts, cell viability and apoptosis were measured. As shown in Fig. 1A, cell viability was significantly decreased with H2O2 treatment, while taurine increased cell viability in a dose-dependent manner. A cell apoptosis assay showed a significant increase in apoptosis following treatment with H2O2 and a dose-dependent decrease following treatment with taurine (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Effects of Taurine on cell viability and apoptosis. (A) Cells were pretreated with or without Taurine at the indicated concentrations (0, 10, 50, 100, 200 mM) for 3 h and then incubated in the presence of H2O2 (100 μM). The cell viability was determined by MTT assay and (B) cell apoptosis by ELISA kit. Data represent means ± SEM of three independent experiments and differences between mean values were assessed by one-way ANOVA. #p<0.05 indicate the significant difference compared with control group; *p<0.05 compared with H2O2-treated group.

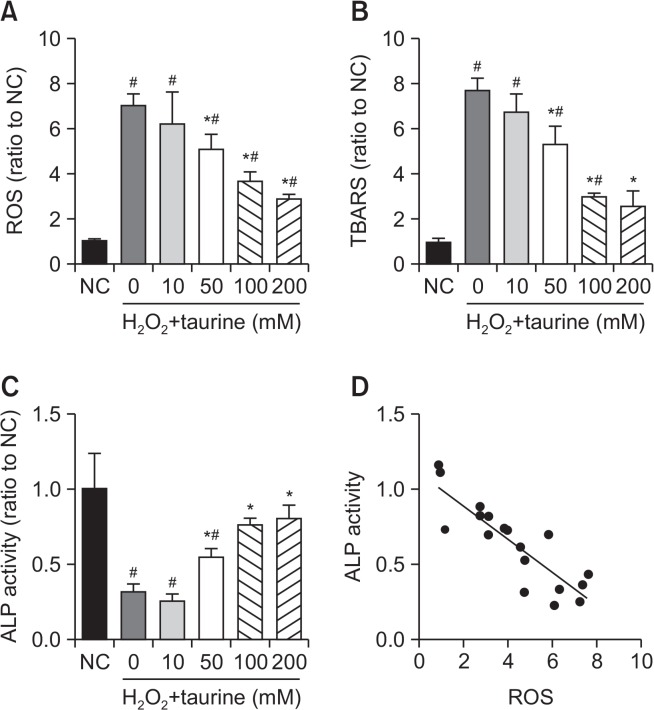

Effects of taurine on H2O2-induced oxidative stress and bone formation

To observe the effects of taurine on oxidative stress following lipid peroxidation, ROS and TBARS levels were measured. As shown in Fig. 2, both ROS and TBARS were upregulated by H2O2, while taurine suppressed the production of ROS and TBARS in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2A, 2B).

Fig. 2.

Effects of Taurine on intracellular ROS, TBARS, and ALP activity after H2O2 treatment. UMR106 cells were pretreated with or without Taurine at the indicated concentrations before treatment with H2O2, (A) ROS generation, (B) TBARS concentration, (C) and ALP activity were measured. Data represent means ± SEM of three independent experiments and differences between mean values were assessed by one-way ANOVA. #p<0.05 indicate the significant difference compared with control group; *p<0.05 compared with H2O2-treated group. (D) A Pearson correlation analysis was performed to investigate the relation between ALP activity and ROS generation. p<0.05 indicate the significant difference.

ALP is the earliest marker of osteoblast proliferation and differentiation. As shown in Fig. 2C, there was a significant decrease in the ALP activity of H2O2-treated osteoblasts. Pre-treatment of osteoblasts with 50, 100, or 200 mM of taurine significantly attenuated H2O2 and reduced ALP activity. Since ALP activity was negatively associated with the production of ROS (Fig. 2D) and generation of ROS was dose-dependently related to taurine, taurine might protect osteoblasts against oxidative stress and promote proliferation and differentiation.

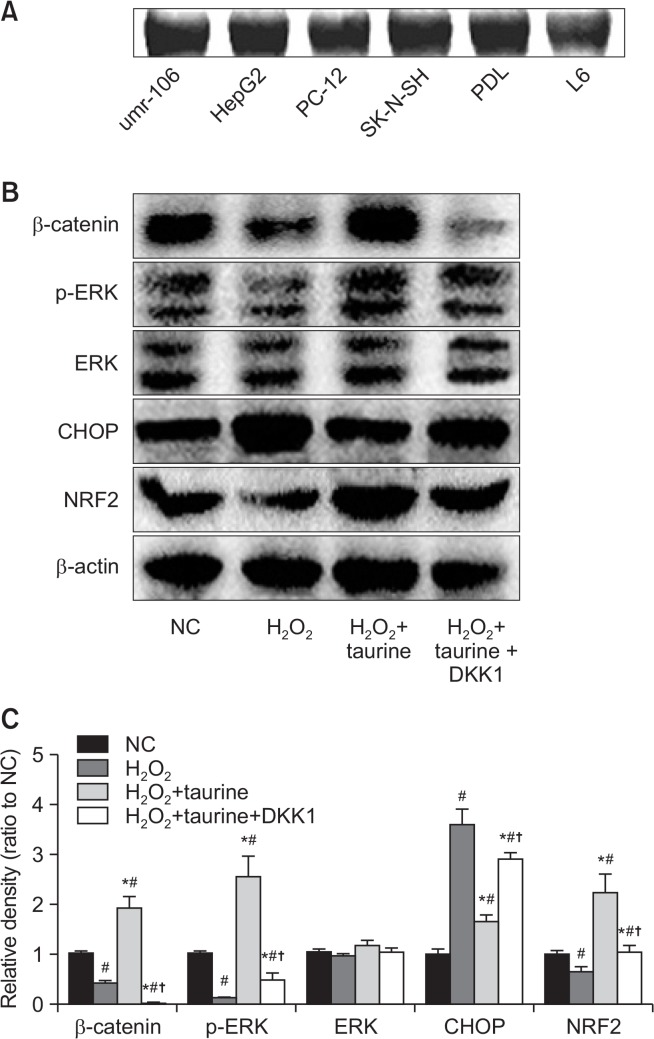

Effects of taurine on the antioxidant signaling pathway

To identify how taurine affects cell apoptosis, we first examined the expression of taurine transporter in osteoblast. As shown in Fig. 3A, osteoblast-like cells (UMR-106) as well as hepatocytes (HepG2), neuronal cells (PC-12, SK-N-SH), and muscle cells (L6) showed strong expression in the taurine transporter. Previous studies reported the protective effects of taurine in liver, neuron, and bone (Son et al., 2007; Jang and Kim, 2013; Roman-Garcia et al., 2014). Therefore, this result taurine may play a crucial role via its transporter in osteoblast.

Fig. 3.

Effects of Taurine on β-catenin, ERK, and NRF2. (A) Expression of taurine transporter was examined in the different cell lines. (B) Cells were pretreated with DKK1 for 1h, then incubated with Taurine (100 mM) for 3 h, followed by exposure of H2O2. Cell lysates were subjected to western blot analysis. (C) Relative density was measured using ImageJ. Data represent means ± SEM of three independent experiments and differences between mean values were assessed by one-way ANOVA. #p<0.05 indicate the significant difference compared with control group; *p<0.05 compared with H2O2-treated group; †p<0.05 indicate the significant difference compared with H2O2+Taurine group.

To explore further the role of taurine in H2O2-induced osteoblastic toxicity, we examined the expression of β-catenin and ERK phosphorylation. H2O2 treatment downregulated the expression of β-catenin and ERK phosphorylation, while taurine promoted the expression of β-catenin and ERK (Fig. 3B, 3C). ER stress is also one of the important pathways involved in oxidative stress, ischemia, and other physiological and pathological conditions (Yang et al., 2017). To determine whether endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-mediated apoptosis pathway was involved in the effect of taurine on H2O2-induced osteoblastic toxicity, the expression of CHOP was measured. The expression of CHOP was upregulated by H2O2, and Taurine could be inhibited the expression. In addition, the antioxidant, Nrf2, and the downstream antioxidants (HO-1, NQO1, GCLC) significantly decreased, while taurine increased the levels of them (Fig. 3B, 3C, 4A).

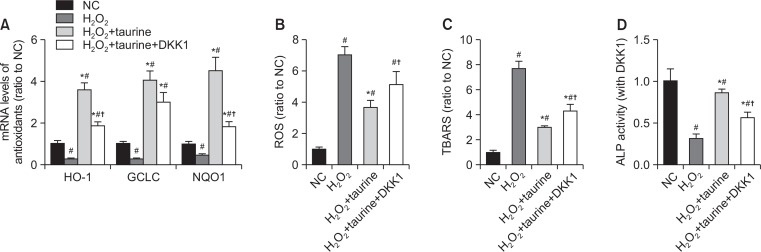

Fig. 4.

Involvement of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in the protective effects of Taurine. Cells were pretreated with DKK1 for 1 h, then incubated with Taurine (100 mM) for 3 h, followed by exposure of H2O2. (A) mRNA levels of NRF2 downstream antioxidants were measured by qRT-PCR. (B) cellular ROS generation (C) levels of TBARS (D) ALP activity. Data represent means ± SEM of three independent experiments and differences between mean values were assessed by one-way ANOVA. #p<0.05 indicate the significant difference compared with control group; *p<0.05 compared with H2O2-treated group; †p<0.05 indicate the significant difference compared with H2O2+Taurine group.

To identify the relationship between β-catenin and ERK, cells were pretreated with DKK1 to inhibit the β-catenin signaling pathway. As shown in Fig. 3B and 3C, ERK expression was reduced in part by DKK1, while CHOP was increased. Antioxidant levels (Nrf2, HO-1, NQO1, GCLC) and ALP activity were also downregulated by DKK1, while generation of ROS and TBARS was significantly increased (Fig. 4).

DISCUSSION

Increased production of ROS, as well as the subsequent oxidative stress, affects bone homeostasis (Bartell et al., 2014), inhibits osteoblast differentiation and proliferation (Qiao et al., 2016), and induces cell apoptosis (Wauquier et al., 2009; Pisoschi and Pop, 2015; Liu et al., 2017). In the present study, the researchers found that taurine could suppress H2O2-induced oxidative stress, significantly reduce osteoblast apoptosis, and promote mineralization through ERK and the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway.

Nrf2, as a transcription factor, is responsible for cellular defense mechanisms against oxidative stress, achieving this by binding to an antioxidant response element (ARE) and regulating the production of multiple antioxidants, including HO-1, NQO1, and GCLC (Nguyen et al., 2009; Suzuki and Yamamoto, 2015). Many studies have reported that the activation of Nrf2 signaling could effectively protect osteoblasts (Li et al., 2016; Han et al., 2017). In the present study, we demonstrated that taurine can efficiently increase the expression of Nrf2 signaling in H2O2-treated osteoblasts and upregulate the mRNA levels of downstream antioxidant enzymes (i.e., HO1, NQO1, and GCLC).

In addition to characterizing the Nrf2 signaling pathway, we identified the upstream mechanism through which taurine may resist oxidative stress. MAPKs play crucial roles in several cellular processes, such as cell proliferation, apoptosis, and immune defense (Soares-Silva et al., 2016). Though MAPKs have been reported to participate in the Nrf2 pathway, the exact functions of each subgroup could vary depending on cell type, incubation conditions, and stimuli (Lee et al., 2014). As one of the major subgroups of MAPKs, ERK is involved in various pathological processes. A number of studies have reported that many chemicals could increase Nrf2 activity by activating ERK (Cheung et al., 2013; Wong et al., 2016). For example, inhibition of the ERK pathway can suppress Nrf2 phosphorylation, as it retards the nuclear translocation of Nrf2 and subsequently decreases antioxidant gene transcription (Lee et al., 2014). The present study also found that taurine activates the ERK pathway in H2O2-treated osteoblasts. This result is consistent with a previous study in which a taurine treatment increased the activation of ERK (Zhang et al., 2011). The data therefore demonstrates that taurine enhances Nrf2 activation and downstream antioxidant expression via its regulatory effect on ERK.

Wnt/β-catenin signaling plays a crucial role in bone development and formation, as it promotes osteoblast differentiation and mineralization (Shim et al., 2013; Nusse and Clevers, 2017). In addition, Wnt/β-catenin signaling increases cell survival and reduces cell apoptosis by activating cellular antioxidant defense systems (Tapia et al., 2006). In recent studies, there is accumulating evidence regarding the interactions between the MAPK and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways. For example, serum phenolic acid induced by diet may enhance bone formation via p38/β-catenin signaling (Chen et al., 2010), and Schnurri-3 can regulate ERK downstream of Wnt signaling to promote osteoblast proliferation (Shim et al., 2013). However, other studies have reported the opposite effects of the MAPK and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways in the pathological progress of diseases. Hu et al. (2009) demonstrated the inhibitory effects of JNK on β-catenin, while Ahn et al. (2010) reported the downregulation of ERK activity and the increased transcriptional activity of β-catenin in curcumin-suppressed adipogenic differentiation. Based on these findings, the relationship between these two signaling pathways may vary depending on the organs, stimuli, and culture conditions. In the present study, we found that taurine significantly increased the expression of β-catenin and that the protective effects induced by taurine are partially eliminated by a Wnt/β-catenin signaling inhibitor (i.e., DKK1). Interestingly, the inhibition of β-catenin by DKK1 not only led to elevated oxidative stress and reduced ALP but also caused the decreased expression of ERK, compared to taurine-treated cells. These results suggest that taurine inhibits oxidative stress-induced apoptosis and promotes osteoblast mineralization by activating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. More importantly, we found that Wnt/β-catenin signaling can regulate ERK phosphorylation, thereby increasing antioxidant response to oxidative stress.

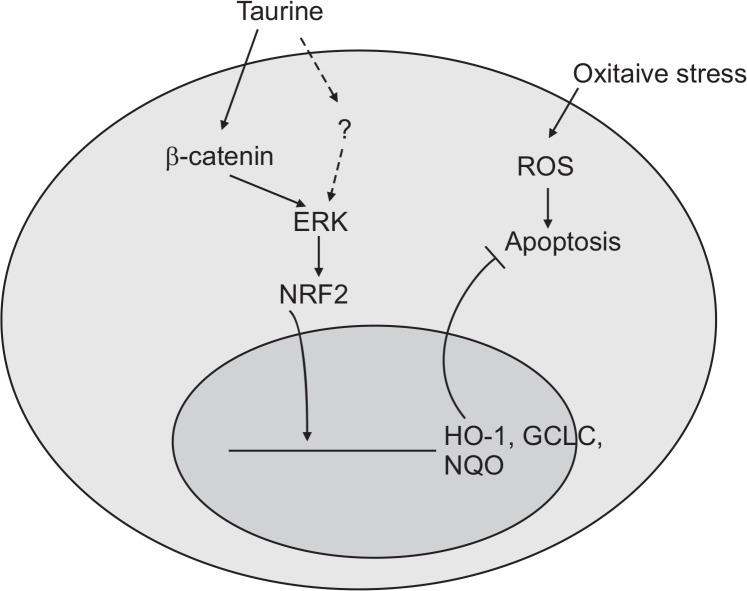

Our findings indicate that taurine activates Nrf2, induces the expression of antioxidant enzymes (i.e., NQO1, HO1, and GCLC), and reduces H2O2-induced cell death by activating ERK and the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in osteoblast cells. Considering the partial reduction of ERK, antioxidants, and ALP activities by DKK1, a Wnt/β-catenin inhibitor, it is possible that other signaling molecules and pathways could be involved (Fig. 5). Thus, to explore other pathways that likely participate in taurine-mediated antioxidant effects, such as the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway (Jang et al., 2016), further research is necessary.

Fig. 5.

A proposed signaling pathway involved in Taurine against H2O2-induced oxidative damage. Schematic diagram shows that aurine activates Nrf2, induces expression of antioxidant enzymes (NQO1, HO1, and GCLC), and reduces H2O2-induced cell death by activating ERK and the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in osteoblast cells. In addition, partial reduction of ERK, antioxidants, and ALP activity by a Wnt/β-catenin inhibitor suggest the involvement of other signaling molecules and pathways.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (81300534, 81300620) and the Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province (2013022030022013022026).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All authors state that they have nothing to disclose and no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Abdal Dayem A, Hossain MK, Lee SB, Kim K, Saha SK, Yang GM, Choi HY, Cho SG. The Role of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) in the biological activities of metallic nanoparticles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18:E120. doi: 10.3390/ijms18010120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn J, Lee H, Kim S, Ha T. Curcumin-induced suppression of adipogenic differentiation is accompanied by activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2010;298:C1510–C1516. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00369.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartell SM, Kim HN, Ambrogini E, Han L, Iyer S, Serra Ucer S, Rabinovitch P, Jilka RL, Weinstein RS, Zhao H, O’Brien CA, Manolagas SC, Almeida M. FoxO proteins restrain osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption by attenuating H2O2 accumulation. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3773. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardo I, Bozinovski S, Vlahos R. Targeting oxidant-dependent mechanisms for the treatment of COPD and its comorbidities. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015;155:60–79. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervellati C, Bergamini CM. Oxidative damage and the pathogenesis of menopause related disturbances and diseases. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2016;54:739–753. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2015-0807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JR, Lazarenko OP, Wu X, Kang J, Blackburn ML, Shankar K, Badger TM, Ronis MJ. Dietary-induced serum phenolic acids promote bone growth via p38 MAPK/beta-catenin canonical Wnt signaling. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2010;25:2399–2411. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung KL, Lee JH, Shu L, Kim JH, Sacks DB, Kong AN. The ras GTPase-activating-like protein IQGAP1 mediates Nrf2 protein activation via the mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) kinase (MEK)-ERK pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:22378–22386. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.444182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai P, Mao Y, Sun X, Li X, Muhammad I, Gu W, Zhang D, Zhou Y, Ni Z, Ma J, Huang S. Attenuation of oxidative stress-induced osteoblast apoptosis by curcumin is associated with preservation of mitochondrial functions and increased Akt-GSK3beta signaling. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2017;41:661–677. doi: 10.1159/000457945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenblatt MB, Shim JH, Zou W, Sitara D, Schweitzer M, Hu D, Lotinun S, Sano Y, Baron R, Park JM, Arthur S, Xie M, Schneider MD, Zhai B, Gygi S, Davis R, Glimcher LH. The p38 MAPK pathway is essential for skeletogenesis and bone homeostasis in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2010;120:2457–2473. doi: 10.1172/JCI42285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han D, Chen W, Gu X, Shan R, Zou J, Liu G, Shahid M, Gao J, Han B. Cytoprotective effect of chlorogenic acid against hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress in MC3T3-E1 cells through PI3K/Akt-mediated Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway. Oncotarget. 2017;8:14680–14692. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi M, Celino FT, Shimizu-Yamaguchi S, Miura C, Miura T. Taurine plays an important role in the protection of spermatogonia from oxidative stress. Amino Acids. 2012;43:2359–2369. doi: 10.1007/s00726-012-1316-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu D, Bi X, Fang W, Han A, Yang W. GSK3b is involved in JNK2-mediated b-catenin inhibition. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6640. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang HJ, Hong EM, Kim M, Kim JH, Jang J, Park SW, Byun HW, Koh DH, Choi MH, Kae SH, Lee J. Simvastatin induces heme oxygenase-1 via NF-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) activation through ERK and PI3K/Akt pathway in colon cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:46219–46229. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang HJ, Kim SJ. Taurine exerts anti-osteoclastogenesis activity via inhibiting ROS generation, JNK phosphorylation and COX-2 expression in RAW264.7 cells. J. Recept. Signal Transduct. Res. 2013;33:387–391. doi: 10.3109/10799893.2013.839999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HY, Yoon JY, Yun JH, Cho KW, Lee SH, Rhee YM, Jung HS, Lim HJ, Lee H, Choi J, Heo JN, Lee W, No KT, Min D, Choi KY. CXXC5 is a negative-feedback regulator of the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway involved in osteoblast differentiation. Cell Death Differ. 2015;22:912–920. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2014.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koizumi Y, Nagai K, Gao L, Koyota S, Yamaguchi T, Natsui M, Imai Y, Hasumi K, Sugiyama T, Kuba K. Involvement of RSK1 activation in malformin-enhanced cellular fibrinolytic activity. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:5472. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-23745-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HS, Lee GS, Kim SH, Kim HK, Suk DH, Lee DS. Anti-oxidizing effect of the dichloromethane and hexane fractions from Orostachys japonicus in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells via upregulation of Nrf2 expression and activation of MAPK signaling pathway. BMB Rep. 2014;47:98–103. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2014.47.2.088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li ST, Chen NN, Qiao YB, Zhu WL, Ruan JW, Zhou XZ. SC79 rescues osteoblasts from dexamethasone though activating Akt-Nrf2 signaling. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016;479:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin P, Tian XH, Yi YS, Jiang WS, Zhou YJ, Cheng WJ. Luteolin-induced protection of H(2)O(2)-induced apoptosis in PC12 cells and the associated pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015;12:7699–7704. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.4400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu WD, Mao L, Ji F, Chen FL, Hao YD, Liu G. Targeted activation of AMPK by GSK621 ameliorates H2O2-induced damages in osteoblasts. Oncotarget. 2017;8:10543–10552. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushita T, Chan YY, Kawanami A, Balmes G, Landreth GE, Murakami S. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 (ERK1) and ERK2 play essential roles in osteoblast differentiation and in supporting osteoclastogenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2009;29:5843–5857. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01549-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T, Nioi P, Pickett CB. The Nrf2-antioxidant response element signaling pathway and its activation by oxidative stress. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:13291–13295. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R900010200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusse R, Clevers H. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling, disease, and emerging therapeutic modalities. Cell. 2017;169:985–999. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisoschi AM, Pop A. The role of antioxidants in the chemistry of oxidative stress: a review. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015;97:55–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao X, Nie Y, Ma Y, Chen Y, Cheng R, Yin W, Hu Y, Xu W, Xu L. Irisin promotes osteoblast proliferation and differentiation via activating the MAP kinase signaling pathways. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:18732. doi: 10.1038/srep18732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman-Garcia P, Quiros-Gonzalez I, Mottram L, Lieben L, Sharan K, Wangwiwatsin A, Tubio J, Lewis K, Wilkinson D, Santhanam B, Sarper N, Clare S, Vassiliou GS, Velagapudi VR, Dougan G, Yadav VK. Vitamin B(1)(2)-dependent taurine synthesis regulates growth and bone mass. J. Clin. Invest. 2014;124:2988–3002. doi: 10.1172/JCI72606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim JH, Greenblatt MB, Zou W, Huang Z, Wein MN, Brady N, Hu D, Charron J, Brodkin HR, Petsko GA, Zaller D, Zhai B, Gygi S, Glimcher LH, Jones DC. Schnurri-3 regulates ERK downstream of WNT signaling in osteoblasts. J. Clin. Invest. 2013;123:4010–4022. doi: 10.1172/JCI69443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares-Silva M, Diniz FF, Gomes GN, Bahia D. The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway: role in immune evasion by trypanosomatids. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:183. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son HY, Kim H, HK Y. Taurine prevents oxidative damage of high glucose-induced cataractogenesis in isolated rat lenses. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol (Tokyo) 2007;53:324–330. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.53.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Yamamoto M. Molecular basis of the Keap1-Nrf2 system. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015;88:93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapia JC, Torres VA, Rodriguez DA, Leyton L, Quest AF. Casein kinase 2 (CK2) increases survivin expression via enhanced beta-catenin-T cell factor/lymphoid enhancer binding factor-dependent transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:15079–15084. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606845103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wauquier F, Leotoing L, Coxam V, Guicheux J, Wittrant Y. Oxidative stress in bone remodelling and disease. Trends Mol. Med. 2009;15:468–477. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong SY, Tan MG, Wong PT, Herr DR, Lai MK. Andrographolide induces Nrf2 and heme oxygenase 1 in astrocytes by activating p38 MAPK and ERK. J Neuroinflammation. 2016;13:251. doi: 10.1186/s12974-016-0723-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Zhang Y, Wang L, Lee S. Levistolide A induces apoptosis via ros-mediated ER stress pathway in colon cancer cells. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2017;42:929–938. doi: 10.1159/000478647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee CS, Manilay JO, Chang JC, Hum NR, Murugesh DK, Bajwa J, Mendez ME, Economides AE, Horan DJ, Robling AG, Loots GG. Conditional Deletion of Sost in MSC-derived lineages Identifies Specific Cell Type Contributions to Bone Mass and B Cell Development. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2018. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zhang L-Y, Zhou Y-Y, Chen F, Wang B, Li J, Deng Y-W, Liu WD, Wang ZG, Li YW, Li DZ, Lv GH, Yin B-L. Taurine inhibits serum deprivation-induced osteoblast apoptosis via the taurine transporter/ERK signaling pathway. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2011;44:618–623. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X2011007500078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou W, Greenblatt MB, Shim JH, Kant S, Zhai B, Lotinun S, Brady N, Hu DZ, Gygi SP, Baron R, Davis RJ, Jones D, Glimcher LH. MLK3 regulates bone development downstream of the faciogenital dysplasia protein FGD1 in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2011;121:4383–4392. doi: 10.1172/JCI59041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]