Abstract

MicroRNAs (miRNAs or miRs) have recently emerged as key regulators of various types of cancer, including non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). The disrupted expression of miRNAs is associated with tumorigenesis and metastasis; however, the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. In this study, we demonstrate that miR-98-5p is downregulated in NSCLC and that miR-98-5p deficiency is associated with an advanced clinical stage and metastasis. A dual-luciferase reporter assay was performed to confirm that transforming growth factor beta receptor 1 (TGFBR1), a key stimulator of tumor proliferation and metastasis, was a direct target of miR-98-5p. miR-98-5p overexpression resulted in the downregulation of TGFBR1 and the suppression of the viability, proliferation, migration and invasion of A549 and H1299 cells. Furthermore, miR-98-5p was demonstrated to be an efficient suppressor of tumor growth in an A549 subcutaneous xenograft tumor mouse model. Finally, miR-98-5p overexpression exerted a significant anti-metastatic effect in a mouse model of pulmonary metastasis. On the whole, the results of the present study suggest that miR-98-5p/TGFBR1 may serve as promising targets for NSCLC therapy.

Keywords: lung cancer, microRNAs, transforming growth factor beta receptor 1, tumorigenesis, metastasis

Introduction

Lung cancer is one of the most frequently diagnosed types of cancer and the leading cause of cancer-associated mortality worldwide (1). Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), which includes squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma, is a highly metastatic subset of lung cancer (2-4). At present, typical treatments for NSCLC include surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy; however, despite advances in these techniques, the median survival period of patients with late-stage and metastatic NSCLC remains unsatisfactory (5-7). As such, developing novel effective treatments for NSCLC is of utmost importance.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs or miRs) are a class of small non-coding RNAs of 20-25 nucleotides in length (8). miRNAs are able to bind to the 3′-untranslated region (3′-UTR) of target genes, leading to mRNA degradation or suppressing the translation of target mRNAs (9-11). It is considered that ~33% of human genes associated with tumorigenesis, embryonic development and inflammation are regulated by miRNAs (12-15). Increasing evidence indicates that tumor cell proliferation, migration and invasion are directly governed by miRNAs, suggesting that miRNAs may be promising therapeutic targets for tumor treatment (16,17).

miR-98-5p, a member of the let-7 family of miRNAs, is associated with a number of types of cancer, including lung cancer, colorectal cancer and breast cancer (18-21). It has been reported that miR-98-5p enhances radiosensitivity and chemosensitivity, while it inhibits proliferation, migration and invasion in NSCLC (22-24). However, the inherent molecular mechanisms through which miR-98-5p affects NSCLC progression remain largely unknown. As such, in this study, we focused on transforming growth factor beta receptor 1 (TGFBR1), which is one of the most established target genes of miR-98-5p. TGFBR1 is involved in the regulation of cellular processes, including motility, differentiation, adhesion, division and apoptosis (25-28). TGFBR1 also plays an important role in tumor progression, with its activation or overexpression often observed in various types of cancer. For example, TGFBR1 has been shown to enhance the migration and invasion of MCF-7 breast cancer cells and to promote the invasion and metastasis of colorectal cancer (29-31). Furthermore, TGFBR1 plays a role in tumor invasion and metastasis by mediating epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) (31). Taken together, these data suggest that TGFBR1 inhibition may serve as a potential target for cancer therapy.

The aim of the present study was to investigate the function of miR-98-5p in NSCLC progression and explore the interaction between miR-98-5p and TGFBR1. The results of our study demonstrate that miR-98-5p attenuates tumor growth and metastasis by suppressing TGFBR1 and EMT signaling in NSCLC.

Materials and methods

Clinical tissue samples

Lung cancer specimens and adjacent normal tissues (n=70) were obtained from patients suffering from NSCLC who had not received any pre-operative radiotherapy and chemotherapy at Wujin People’s Hospital of Changzhou (Changzhou, China) from January, 2010 to May, 2013. The patients’ sex distribution (male, n=39; female, n=31) and age distribution in years (≥60, n=38; <60, n=32; age range, 27 to 79 years; mean age, 58.88±12.65 years) were recorded. The diagnosis of lung cancer was performed by our surgeons and pathologists. The collected tissues were stored at −80°C in liquid nitrogen until use. Tissues and information of patients were obtained with written informed consent. The procedures used in this study were approved by the Human Ethics Committee at the Wujin People’s Hospital of Changzhou. All the experiments were conducted according to the approved guidelines.

Cell lines and animals

The human NSCLC A549 (no. CCL-185), H1299 (no. CRL-5803), ANIP-973 (no. CS-0168) and GLC-82 (no. ZY-H065) cell lines (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) were cultured in DMEM (Gibco/Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

A total of 10 male NOD/SCID mice (6-8 weeks old) were purchased from HFK Bio-Technology Co. (Beijing, China). Mice were housed under specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions and were quarantined for 1 week prior to treatment. The animals were housed in a controlled environment with a temperature of 20-22°C, relative humidity of 50-60% and 12 h light/dark cycles, and were provided with access to food and water ad libitum. All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with the protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Treatment Committee of Wujin People’s Hospital of Changzhou. All animals were treated humanely throughout the experimental period.

RNA preparation and reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from the collected tissues or cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen/Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was converted into cDNA using a Reverse Transcription kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). PCR was then performed using Taq polymerase (Takara Bio, Inc., Otsu, Japan). Stem-loop primers (Guangzhou RiboBio Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, China) were used to detect miRNAs. U6 small nucleolar RNA and GAPDH were used for normalization. The relative expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method (32) (CFX manager software 3.1; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA). The primers used were as follows: hsa-miR-98-5p forward, 5′-ACACTCCCUAUACAACUUAC-3′ and reverse, 5′-GGGAAAGUAGUGAGGCCTCAGA-3′; TGFBR1 forward, 5′-TCGTCTGCATCTCACTCAT-3′ and reverse, 5′-GATAAATCTCTGCCTCACG-3′; and GAPDH forward, 5′-TCTCTGCTCCTCCTGTTC-3′ and reverse, 5′-GGTTGAGCACAGGGTACTTTATTGA-3′. Quantitative PCR was carried out using SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (Tli RNaseH Plus; 2X; 6 µl), 0.5 µl PCR forward primer (10 µM), 0.5 µl PCR reverse primer (10 µM), 1 µl cDNA solution, 3 µl RNase-free dH2O, total was 10 µl. The cycling conditions for PCR were as follows: Stage 1: 95°C, 30 sec; repeat: 1; stage 2: 95°C, 5 sec, 60°C, 34 sec; repeat: 40; stage 3: dissociation.

Transfection

Hsa-miR-98-5p mimics, hsa-miR-98-5p inhibitors and the corresponding negative controls were purchased from Obio Technology (Shanghai, China) and transfected into the A549, H1299, ANIP-973 and GLC-82 cells using Lipofectamine® 2000 (Invitrogen/Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. At 48 h following transfection, the cells were collected for use in further experiments.

Cell viability and congenic survival

Cell viability was assessed using an MTT assay. The cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 2,000 cells/well. After 12 h, the cells were transfected with miR-98-5p mimics or miR-NC. At 24, 48, 72 or 96 h following transfection, 20 µl MTT solution (5 mg/ml; Amresco, Inc., Framingham, MA, USA) was added to each well followed by incubation at 37°C for 4 h. The cells were subsequently treated with 200 µl DMSO to dissolve the precipitated crystals. Finally, the absorbance of each well was measured using a microplate reader (EL10A; Biobase, Jinan, China) at 570 nm. All experiments were performed 3 times. Data are presented as the means ± standard deviation (SD).

The cells were seeded in 6-well plates (500 cells/well) and incubated at 37°C for 12 h. Following transfection with miR-98-5p mimics or miR-NC, the cells were further incubated at 37°C for 6-8 days. The cells were fixed with methanol for 10 min and stained with 0.1% crystal violet at room temperature for 30 min. Images were subsequently captured using a microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Cell migration and invasion assay

The cell migratory and invasive abilities were investigated using a 24-well plate with 8-µm pore size Boyden chamber inserts. For the migration assays, 4×104 cells were seeded into the upper chamber without a coated membrane. For the invasion assays, 1×105 cells were seeded into the upper chamber with a Matrigel-coated membrane. The cells in the upper chamber were transfected with miR-98-5p mimics or inhibitors and suspended in 200 µl serum-free DMEM. The control groups were transfected with corresponding negative controls. A total of 800 µl DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS was added to the lower chamber. The chambers were incubated for 24 h at 37°C and the non-migrated and non-invasive cells remaining in the upper chamber were removed using a cotton swab. Migrated or invaded cells in the lower chamber were fixed with methanol and stained with 0.1% crystal violet at room temperature for 20 min. Finally, the cells were imaged by the microscope (Olympus) and counted using high-power magnifications.

Wound healing assay

The cells were seeded in 6-well plates (5×105 cells/well) and incubated at 37°C for 12 h. When the cells reached 90% confluence, a scratch wound was made using a 10-µl pipette tip. The cells were subsequently washed with PBS to remove cell debris and transfected with miR-98-5p mimics or inhibitors. The control groups were transfected with corresponding negative controls. The cells were incubated with DMEM supplemented with 1% FBS for 24 h, following which images were captured under a microscope (Olympus).

Western blot analysis

Western blot assays were performed to measure the expression of target proteins. Total cellular proteins were extracted from the cultured cells using lysis buffer [20 mM Tris (pH7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaF and 0.1% NP-40]. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE (10%, w/v) and transferred onto PVDF membranes, which were then blocked using 5% skim milk for 2 h at room temperature. The membranes were subsequently incubated with target primary antibodies against the following: MMP-9 [13667S; Cell Signaling Technology (CST), Danvers, MA, USA], vimentin (10R-1903; Fitzgerald Industries International, Acton, MA, USA), α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA; 19245; CST), TGFBR1 (70R-36484) and β-actin (10R-10263) (both from Fitzgerald Industries International) at 4°C overnight. The dilution used for MMP-9, vimentin, α-SMA and TGFBR1 was 1:100, and the dilution used for β-actin was 1:1,000. Following incubation with horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary antibodies (A0216; Byotime, Shanghai, China) which were diluted at 1:1,000 at 37°C for 2 h, the protein bands were visualized using a chemiluminescence (ECL) detection system and images were captured.

Dual-luciferase reporter assay

The 3′-UTR of wild-type (WT) and mutant TGFBR1 were amplified from human genomic DNA and individually inserted into pmiR-RB-REPORT™ luciferase vectors (Obio, Shanghai, China). The A549 cells were co-transfected with 200 ng of mutant or WT pmiR-RB-REPORT™ plasmid and 100 ng of miR-98-5p mimics or miR-NC Following incubation for 36 h, and luciferase activity was measured with a Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

In vivo anti-tumor evaluation

A549 cells suspensions (1×107 cells; 200 µl) were subcutaneously injected into the right flanks of NOD/SCID mice to establish a xenograft NSCLC model. After 6 days, tumor volume reached ~200 mm3, and the mice were randomly divided into 2 groups as follows: The control (n=5) and miR-98-5p mimic (n=5) group. A total of 5 µg/mouse plasmid was administered every 3 days. The treatment was terminated when mice in the control group became moribund (at day 21). Mice were sacrificed, and tumors were harvested, weighed and imaged. Finally, tumors were collected for further hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and immunohistochemical evaluation. Tissues were collected, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin and sectioned (5 µm thickness). After dewaxing and rehydration, the sections were stained with H&E at room temperature for 10 sec and imaged under a light microscope (Olympus). For immunohistochemistry, the sections were respectively incubated with primary rat anti-mouse antibody Ki-67 (9449; CST; dilution: 1:400), MMP-9 (13667S; CST; dilution: 1:325) and TGFBR1 (70R-36484; Fitzgerald Industries International; dilution: 1:200), and then treated with secondary antibody biotinylated goat anti-rat immunoglobulin (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA). The sections were incubated with streptavidin-peroxidase and DAB solution (Solarbio, Beijing, China) at 37°C for 20 min to visualize the biotinylated goat anti-rat immunoglobulin. The sections were then treated with hematoxylin at room temperature for 10 sec to stain the nuclei of the tumor cells. Finally, the sections were imaged and examined under a light microscope (Olympus).

In vivo anti-metastasis assessment

A total of 1×106 of A549 stable luciferase reporter cells suspended in 100 µl PBS were injected into NOD/SCID mice via the tail vein to establish a model of pulmonary metastasis. At 3 days after inoculation, 10 mice were randomly divided into the control and miR-98-5p mimics groups (n=5) and treated with 5 µg miR-98-5p mimic plasmids or control plasmids, respectively, every 3 days. At 5, 10 and 15 days following inoculation, mice were administered with D-luciferin (3 mg/mouse) for analysis. Bioluminescence was then detected from lung metastatic tumors was detected using an IVIS Lumina In Vivo Imaging System (Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA). Finally, the lungs were harvested from each mouse to count the metastatic nodes and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for further H&E evaluation.

Statistical analysis

The results are presented as the means ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 17.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The significance among multiple groups was evaluated using one-way ANOVA followed by Newman-Keuls (SNK) t-test. Significant differences between 2 groups (parametric) were analyzed using a Student’s t-test, and significant differences between 2 groups (non-parametric) were analyzed by the Mann-Whitney U test. A value of P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

miR-98-5p is downregulated in NSCLC and is associated with progression

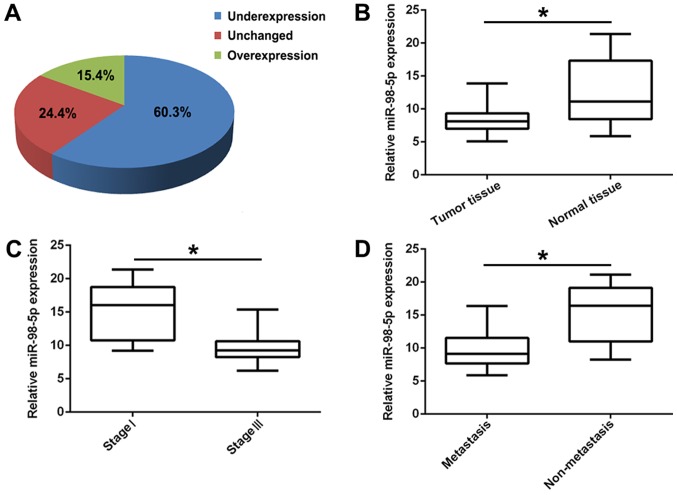

Lung cancer progression is a complex process associated with the activation of oncogenes and the silencing of tumor suppressor genes (32-34). It has been reported that miRNA dysregulation is significantly associated with tumorigenesis and cancer progression (35). In this study, to confirm the biological function of miR-98-5p in NSCLC, we first detected its expression in 70 human primary lung tumor tissues and adjacent normal lung tissues by RT-PCR. The results revealed that miR-98-5p expression was significantly downregulated in the tumor tissues (60.3%) compared with in the controls (Fig. 1A and B; P<0.01). In addition, the expression of miR-98-5p in patients with advanced NSCLC (stage III; n=41) was significantly decreased compared with that in patients with the early stage NSCLC (stage I; n=29; P<0.05; Fig. 1C). Furthermore, compared with non-metastatic NSCLC (n=25), miR-98-5p expression was distinctly downregulated in metastatic NSCLC (n=45; P<0.05, Fig. 1D). These results suggest that miR-98-5p is downregulated in NSCLC and is associated with NSCLC progression.

Figure 1.

miR-98-5p is downregulated in human NSCLC tissues and is associated with progression. (A) The expression levels of miR-98-5p in 70 paired NSCLC tissues and adjacent normal tissues. (B) The expression levels of miR-98-5p were downregulated in NSCLC tissues in comparison with adjacent normal tissues. (C) The expression levels of miR-98-5p in different clinical stages (I and III) in NSCLC. (D) The expression levels of miR-98-5p in metastatic and non-metastatic NSCLC. NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer. *P<0.05.

miR-98-5p overexpression inhibits NSCLC tumorigenesis in vitro

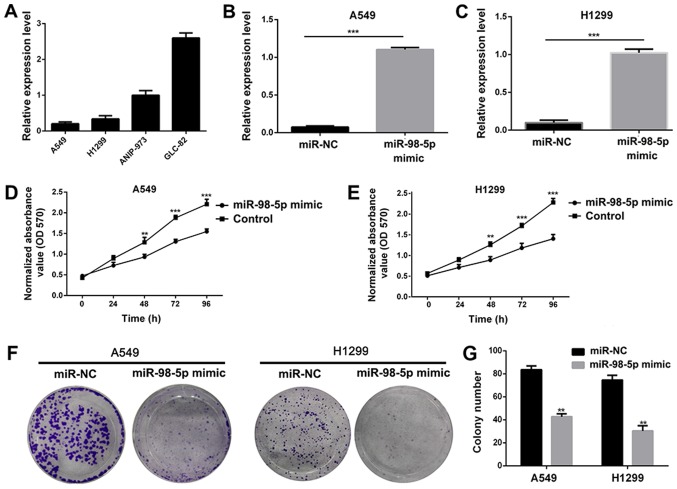

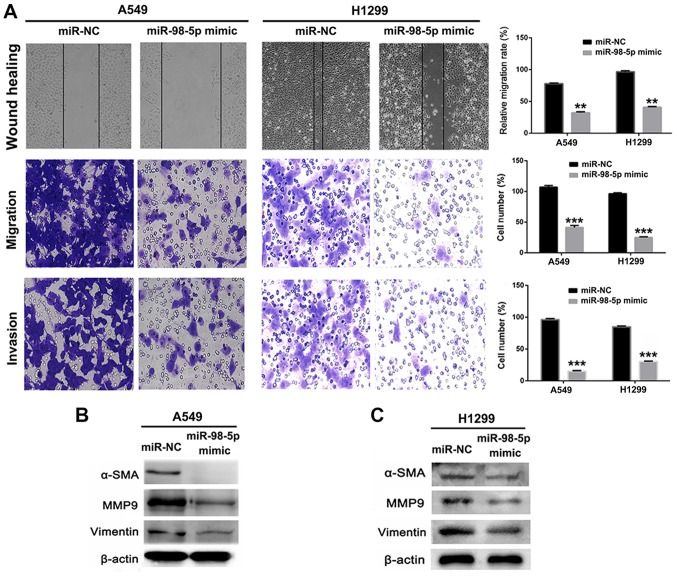

In order to investigate the biological role of miR-98-5p in NSCLC, we measured the expression of miR-98-5p in 5 different NSCLC cell lines. It was observed that miR-98-5p expression was downregulated in the A549 and H1299 cells, but was increased in the ANIP-973 and GLC-82 cells (Fig. 2A). We thus transfected the A549 and H1299 cells with plasmid miR-98-5p mimics to restore miR-98-5p expression, and the results revealed that miR-98-5p expression was significantly increased following transfection (P<0.001; Fig. 2B and C). Following transfection with miR-98-5p mimics, the viability (Fig. 2D and E) and colony formation abilities (Fig. 2F and G) of the A549 and H1299 cells were significantly suppressed, indicating an anti-proliferative effect of miR-98-5p mimics. A number of studies have demonstrated that miRNA dysregulation is associated with tumor migration and invasion (33,34), and we thus used miR-98-5p mimics to restore the expression level of miR-98-5p in the A549 and H1299 cells. The results of a wound healing assay revealed that the migration of the A549 and H1299 cells was suppressed following transfection with miR-98-5p mimic (P<0.05; Fig. 3A). Furthermore, Transwell assays revealed that the migration and invasion of A549 and H1299 cells were distinctly suppressed by transfection with miR-98-5p mimics (P<0.001). The expression of proteins associated with tumor metastasis and EMT was measured using western blotting following treatment with miR-98-5p mimics. As shown in Fig. 3B and C, the expression of MMP-9, α-SMA and vimentin was significantly downregulated in the A549 and H1299 cells following transfection with miR-98-5p mimics. These results suggested that the restoration of miR-98-5p expression significantly suppressed the viability, proliferation, migration and invasion of both the A549 and H1299 cells, acting as a tumor suppressor in vitro.

Figure 2.

Restoration of miR-98-5p expression suppresses cell proliferation. (A) The expression level of miR-98-5p in 4 NSCLC cell lines. (B and C) Changes in the expression levels of miR-98-5p in A549 and H1299 cells following transfection with miR-98-5p mimic. (D and E) Viability of A549 and H1299 cells were measured after transfection with miR-98-5p mimic. (F and G) Anti-proliferation evaluation of miR-98-5p mimic in A549 and H1299 cells NSCLC. NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer. **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. control.

Figure 3.

Restoration of miR-98-5p expression suppresses cell migration and invasion. (A) Anti-mobility, anti-migration and anti-invasion assessments of miR-98-5p mimic in A549 and H1299 cells. Magnification, ×200. (B and C) Metastasis associated proteins were analyzed by western blot analysis in A549 and H1299 cells following transfection with miR-98-5p mimic. **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. miR-NC (control).

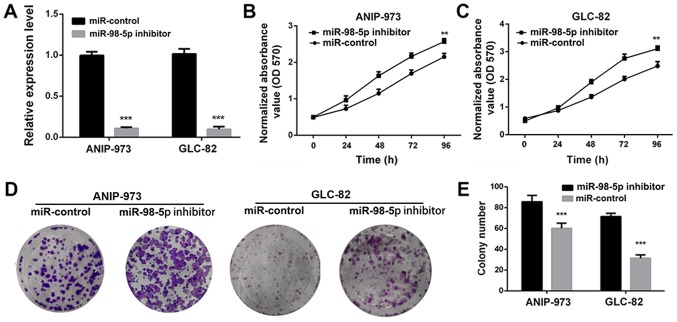

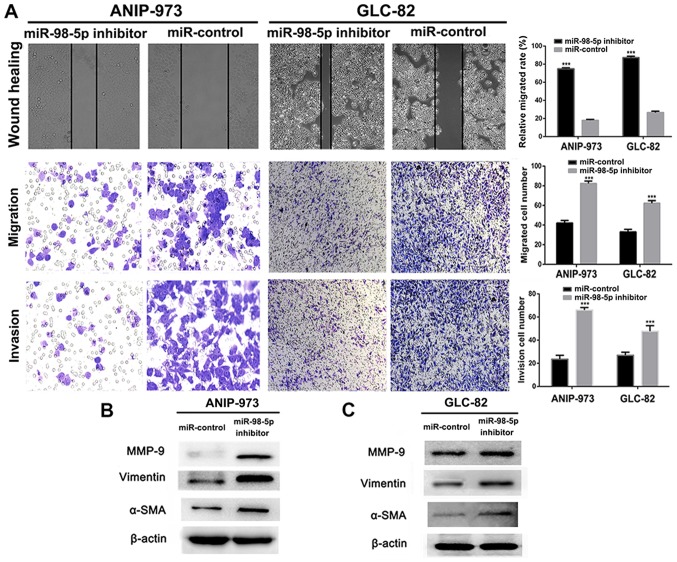

To further confirm that miR-98-5p acts as a tumor suppressor in NSCLC, we utilized a plasmid miR-98-5p inhibitor. Compared with the miR-controls, transfection with miR-98-5p inhibitors significantly decreased the expression of miR-98-5p in both the ANIP-973 and GLC-82 cells (Fig. 4A; P<0.001). When miR-98-5p expression was downregulated, the viability (Fig. 4B and C) and colony formation ability (Fig. 4D and E) of the ANIP-973 and GLC-82 cells were increased. Furthermore, cell migration and invasion were investigated following the knockdown of miR-98-5p. It was demonstrated that the mobility of the ANIP-973 and GLC-82 cells was increased following miR-98-5p downregulation (Fig. 5A). In addition, the migration and invasion of the ANIP-973 and GLC-82 cells were distinctly enhanced following transfection with miR-98-5p inhibitors. When the ANIP-973 and GLC-82 cells were transfected with the miR-98-5p inhibitors, the expression levels of metastasis-associated proteins (MMP-9, α-SMA and vimentin) were upregulated, which was in agreement with the wound healing and Transwell assay results (Fig. 5B and C). Taken together, these results suggest that miR-98-5p downregulation enhances the viability, proliferation, migration and invasion of NSCLC cells; in other words, miR-98-5p inhibits NSCLC tumorigenesis in vitro.

Figure 4.

Downregulation of miR-98-5p in ANIP-973 and GLC-82 cells enhances cell proliferation. (A) Changes in the expression levels of miR-98-5p in ANIP-973 and GLC-82 cells following transfection with miR-98-5p inhibitor. (B and C) Viability of ANIP-973 and GLC-82 cells was measured after transfection with miR-98-5p inhibitor. (D and E) Anti-proliferative evaluation of miR-98-5p inhibitor in ANIP-973 and GLC-82 cells. **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. miR-control.

Figure 5.

Downregulation of miR-98-5p in ANIP-973 and GLC-82 cells enhances cell migration and invasion. (A) Anti-mobility, anti-migration and anti-invasion assessments of miR-98-5p inhibitor in ANIP-973 and GLC-82 cells. Magnification, ×200. (B and C) Metastasis associated proteins were analyzed by western blot analysis in ANIP-973 and GLC-82 cells following transfection with miR-98-5p inhibitor. ***P<0.001 vs. miR-control.

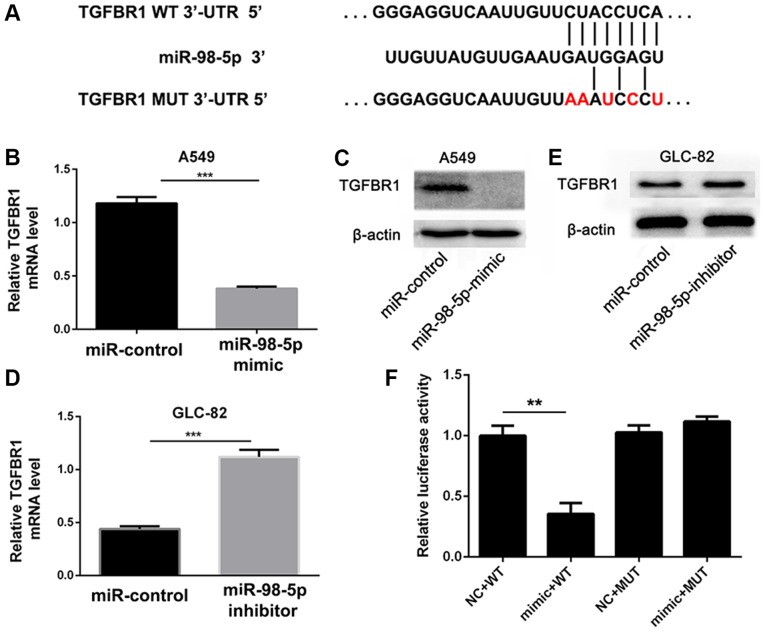

TGFBR1 is a target of miR-98-5p

In order to further investigate the mechanisms through which miR-98-5p affects NSCLC cell progression, we used the computational prediction program TargetScan (www.targetscan.org) to predict target genes. In total, 60 genes were simultaneously predicted by the TargetScan databases, and TGFBR1 was detected as a candidate gene related to NSCLC based on its associated Gene Ontology (GO) terms and also harbors miR-98-5p binding sites, suggesting that TGFBR1, which stimulates tumor cell proliferation, migration and invasion via the TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway (35-38), was identified as a potential target of miR-98-5p (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6.

TGFBR1 is a target gene of miR-98-5p. (A) TGFBR1 is predicted to be a target of miR-98-5p. (B and C) Changes in mRNA and protein levels of TGFBR1 following transfection with miR-98-5p mimic in A549 cells. (D and E) Changes in mRNA and protein levels of TGFBR1 following transfection with miR-98-5p inhibitor in GLC-82 cells. (F) TGFBR1 3’-UTR luciferase reporter assays in A549 cells. TGFBR1, transforming growth factor beta receptor 1. **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. miR-control.

To confirm that TGFBR1 is a downstream target of miR-98-5p, we transfected the A549 cells with miR-98-5p mimics and found that TGFBR1 expression was significantly decreased (P<0.001; Fig. 6B and C). Conversely, TGFBR1 expression was upregulated in the GLC-82 cells following miR-98-5p knockdown (P<0.001; Fig. 6D and E). A dual-luciferase reporter assay was also performed to further verify that miR-98-5p regulates TGFBR1. The WT TGFBR1 3′-UTR (pmiR-RB-REPORT™-TGFBR1-3′-UTR-WT) and mutated TGFBR1-3′-UTR (pmiR-RB-REPORT™-TGFBR1-3′-UTR-MUT) were cloned and co-transfected with miR-98-5p or miR-NC into A549 cells. As shown in Fig. 6F, the luciferase activity of pmiR-RB-REPORT™-TGFBR1-3′-UTR-WT was distinctly inhibited by miR-98-5p mimics compared with miR-NC. However, no significant differences were observed in the luciferase activity of pmiR-RB-REPORT™-TGFBR1-3′-UTR-MUT in the presence of miR-98-5p mimics or miR-NC. These results suggest that miR-98-5p directly targets the 3′-UTR of TGFBR1.

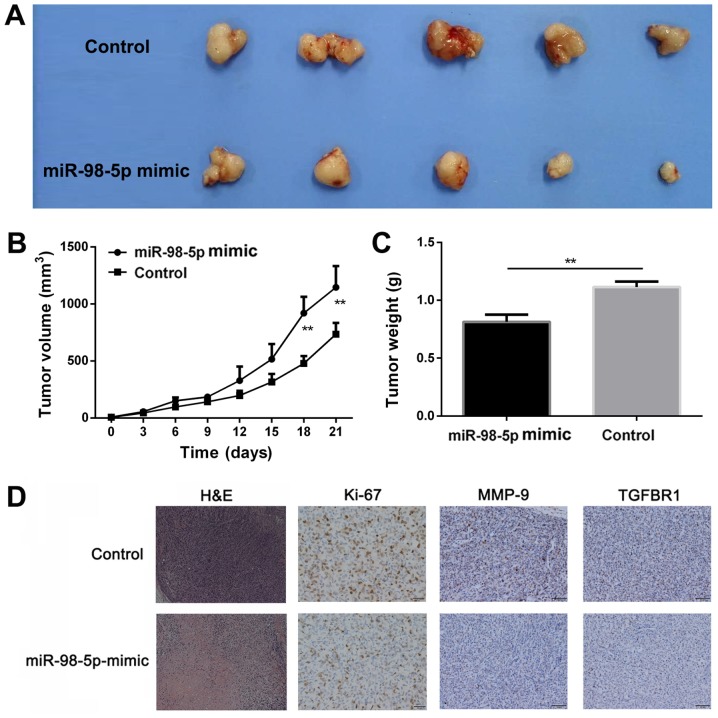

miR-98-5p suppresses tumor growth in vivo

Based on the anti-proliferative effects of miR-98-5p in vitro, these effects were further assessed using a xenograft NSCLC mouse model. Compared with the control group, mice in the miR98-5p mimics group exhibited a significantly slower tumor growth (P<0.01; Fig. 7A and B). Tumor weight was considerably reduced in the miR-98-5p mimic group (0.81±0.091 g) compared with the control group (1.13±0.082 g; P<0.01; Fig. 7C), indicating that miR-98-5p exerted a significant anti-tumor effect. Pathological analysis was performed to evaluate the anti-tumor effects of miR-98-5p (Fig. 7D). H&E staining of the tumor sections revealed preferable anti-proliferative effects in the miR-98-5p mimics group. The number of Ki-67-positive cells in the tumor sections was considerably lower in the miR-98-5p mimic group. Furthermore, TGFBR1 expression was upregulated in the control group compared with the miR-98-5p mimic group. The expression of MMP-9 was decreased in the miR-98-5p mimics group, which is in agreement with the results of immunohistochemical TGFBR1 staining. Taken together, these results suggest that miR-98-5p exerts significant anti-tumor effects in vivo.

Figure 7.

miR-98-5p inhibits tumor growth in vivo. (A) Representative images of tumors after different treatments at day 21. (B) Inhibition of tumor growth in the subcutaneous xenograft tumor model of A549 cells after the different treatments. (C) Weight of tumors after different treatments at day 21. (D) H&E evaluation and immunohistochemistry analysis of Ki-67, MMP-9 and TGFBR1 in tumor sections after different treatments. Magnification, ×200. TGFBR1, transforming growth factor beta receptor 1. **P<0.01 vs. control.

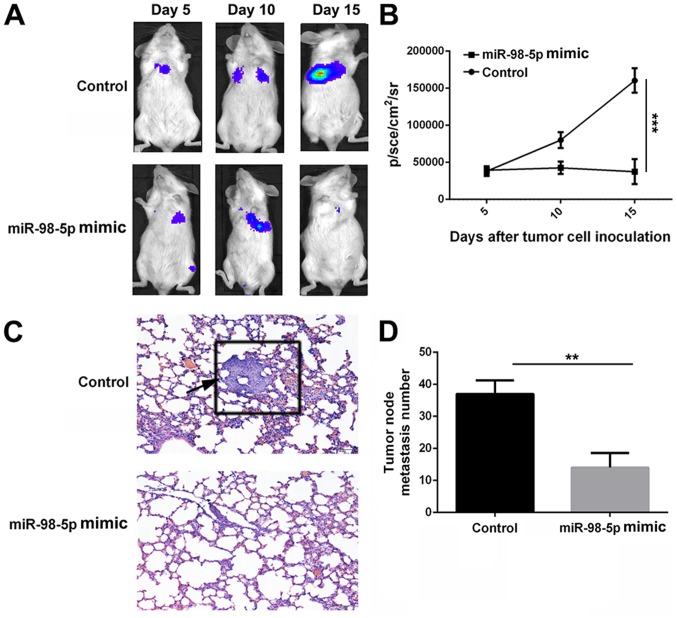

miR-98-5p suppresses tumor metastasis in vivo

A pulmonary metastasis model of A549-luciferase cells in NOD/SCID mice was used to evaluate the anti-metastatic effect of miR-98-5p mimics. Bioluminescence at the lung site, which indicates metastatic tumor cells, increased rapidly in the control group following implantation. However, bioluminescence remained largely unchanged in the miR-98-5p mimic treatment group. At 15 days after tumor cell implantation, bioluminescence was significantly lower in the miR-98-5p mimic group (37475±16967.87 p/sec/cm2/sr) compared with the control group (160432±16443.39 p/sec/cm2/sr; P<0.001). The harvested lung tissues were subjected to H&E staining and metastatic nodes were counted. As shown in Fig. 8D, the number of metastatic nodes in the miR-98-5p group was decreased compared with the control group. Furthermore, H&E staining of the lung tissue sections revealed fewer tumor nodes in the miR-98-5p group compared with the control group (Fig. 8C). These results suggest that miR-98-5p is able to effectively inhibit tumor metastasis in vivo.

Figure 8.

miR-98-5p suppresses tumor metastasis in vivo. (A and B) Bioluminescence imaging and quantitation analysis of NOD//SCID mice bearing pulmo-SCID mice bearing pulmo SCID mice bearing pulmonary metastasis model of A549-luciferase cells after the different treatments at determined time points (5, 10 and 15 days). (C) H&E staining assessment of lung tissues from control and miR-98-5p mimic groups. Arrow indicates a metastatic tumor nodule in lung section. Magnification, ×200. (D) Metastatic tumor nodes of lung tissues from control and miR-98-5p mimic groups. **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. control.

Discussion

Lung cancer is a complex process which is related to the activation of oncogenes and the silencing of tumor suppressor genes (39-41). It has been reported that miRNAs are significantly associated with tumorigenesis, progression and metastasis (42). Moreover, the disrupted expression of miRNAs is commonly found in human NSCLC. In this study, the role of miR-98-5p in lung cancer was investigated and the underlying molecular mechanisms were examined.

A previous study revealed that miR-98 expression was markedly decreased both in lung cancer tissues and in immortal cancer cell lines (18). In this study, we first identified miR-98-5p was an anti-tumor miRNA in NSCLC that was significantly downregulated in tumor tissues in comparison with normal tissues. The expression levels of miR-98-5p in advanced NSCLC were notably lower than those in tissues from patients with early stages of disease. Furthermore, compared with non-metastatic NSCLC, the miR-98-5p expression levels in metastatic NSCLC were distinctly downregulated. Thus, it was suggested from the above results that miR-98-5p was downregulated in NSCLC and was associated with progression in NSCLC, in agreement with previous studies (18,43).

An increasing number of studies have indicated that miR-98 suppresses the proliferation, migration and invasion of various tumor cells. For example, miR-98 has been shown to inhibit the proliferation, invasion and migration, and promote the apoptosis of breast cancer cells by binding to HMGA2 (44). Cai et al also reported that SNHG16 contributed to breast cancer cell migration by competitively binding miR-98 (45). In the current study, we evaluated the biological roles of miR-98-5p in NSCLC in vitro. We demonstrated that transfection with miR-98-5p mimics suppressed the proliferation, colony formation and migration of NSCLC cells. However, the decreased expression of miR-98-5p promoted tumor cell proliferation, colony formation and migration. Various studies have indicated that disrupted levels of miRNAs are closely associated with tumor migration and invasion (16,17). In this study, to investigate the anti-metastatic mechanisms of action of miR-98-5p, we used western blot analysis to demonstrate that miR-98-5p impairs the metastasis of tumor cells via the EMT process. In brief, the restoration of the expression levels of miR-98-5p which resulted from transfection with miR-98-5p mimics significantly suppressed the viability, proliferation, migration and invasion of NSCLC cells, that is to say, miR-98-5p is a tumor suppressor and inhibits NSCLC tumorigenesis in vitro.

To further elucidate the underlying mechanisms of action of miR-98-5p as regards the development of NSCLC, we carried out in vitro experiments using NSCLC cell lines and certified that TGFBR1 was a downstream target of miR-98-5p. Due to the excellent anti-proliferative efficiency of miR-98-5p in vitro, we utilized it for further anti-tumor assessment in a xenograft NSCLC mouse model. Mice in the miR-98-5p mimics group exhibited a significantly slower tumor growth rate, and the tumor weight of the mice in the miR-98-5p mimic group was considerably less than that of the control group. Pathological analysis revealed that preferable anti-proliferative efficiency was found in the miR-98-5p mimics group. Therefore, the above results demonstrated that miR-98-5p exerted efficient anti-tumor effects in vivo. On account of the considerable anti-metastatic efficacy of miR-98-5p mimics in vitro, we exploited a pulmonary metastasis model of A549 reporter luciferase cells in NOD/SCID mouse to evaluate the anti-metastatic efficacy of the miR-98-5p mimic. The metastatic tumor cells which were located in the lung site were distinctly decreased in the miR-98-5p-transfected group in comparison with the control group, indicating that miR-98-5p effectively inhibited tumor metastasis in vivo.

In conclusion, the results of the present study suggest that miR-98-5p, which is downregulated in NSCLC and is associated with tumor progression, effectively inhibits the proliferation, migration and invasion of NSCLC cells in vitro by targeting TGFBR1. In addition, miR-98-5p was observed to have considerable anti-tumor efficacy in an A548 subcutaneous xenograft tumor mouse model. Furthermore, miR-98-5p significantly suppressed tumor metastasis in a mouse model of pulmonary metastasis. Thus, miR-98-5p and TGFBR1 may be potential therapeutic candidates and targets for NSCLC treatment.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was financially supported by Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20151175).

Availability of data and materials

All the data generated or analyzed during this study is included in this published article or are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

FJ and QW conceived and designed the study. QY, YC and XZ acquired and analyzed the data. WL and QL interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. FJ, QY and QW critically revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Tissues and information of patients were obtained with written informed consent. Procedures involving patients in this study were approved by the Human Ethics Committee at the Wujin People’s Hospital of Changzhou. All the animal experiments in this study were performed according to the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD, USA) guidelines and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Treatment Committee of Wujin People’s Hospital of Changzhou.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Tsao AS, Scagliotti GV, Bunn PA, Jr, Carbone DP, Warren GW, Bai C, de Koning HJ, Yousaf-Khan AU, McWilliams A, Tsao MS, et al. Scientific Advances in Lung Cancer 2015. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11:613–638. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta GP, Massagué J. Cancer metastasis: Building a framework. Cell. 2006;127:679–695. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsiao SH, Chung CL, Chou YT, Lee HL, Lin SE, Liu HE. Identification of subgroup patients with stage IIIB/IV non-small cell lung cancer at higher risk for brain metastases. Lung Cancer. 2013;82:319–323. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ardizzoni A, Tiseo M, Boni L, Di Maio M, Buffoni L, Belvedere O, Grossi F, D’Alessandro V, de Marinis F, Barbera S, et al. Randomized phase III PITCAP trial and meta-analysis of induction chemotherapy followed by thoracic irradiation with or without concurrent taxane-based chemotherapy in locally advanced NSCLC. Lung Cancer. 2016;100:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2016.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao Z, Su Z, Zhang W, Luo M, Wang H, Huang L. A randomized study comparing the effectiveness of microwave ablation radioimmunotherapy and postoperative adjuvant chemoradiation in the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer. J BUON. 2016;21:326–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hall RD, Le TM, Haggstrom DE, Gentzler RD. Angiogenesis inhibition as a therapeutic strategy in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2015;4:515–523. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2218-6751.2015.06.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.John B, Enright AJ, Aravin A, Tuschl T, Sander C, Marks DS. Human MicroRNA targets. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tutar L, Tutar E, Özgür A, Tutar Y. Therapeutic Targeting of microRNAs in Cancer: Future Perspectives. Drug Dev Res. 2015;76:382–388. doi: 10.1002/ddr.21273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sethi S, Ali S, Sethi S, Sarkar FH. MicroRNAs in personalized cancer therapy. Clin Genet. 2014;86:68–73. doi: 10.1111/cge.12362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Monroig PC, Chen L, Zhang S, Calin GA. Small molecule compounds targeting miRNAs for cancer therapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2015;81:104–116. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kane NM, Thrasher AJ, Angelini GD, Emanueli C. Concise review: MicroRNAs as modulators of stem cells and angiogenesis. Stem Cells. 2014;32:1059–1066. doi: 10.1002/stem.1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vira D, Basak SK, Veena MS, Wang MB, Batra RK, Srivatsan ES. Cancer stem cells, microRNAs, and therapeutic strategies including natural products. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2012;31:733–751. doi: 10.1007/s10555-012-9382-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun X, Jiao X, Pestell TG, Fan C, Qin S, Mirabelli E, Ren H, Pestell RG. MicroRNAs and cancer stem cells: The sword and the shield. Oncogene. 2014;33:4967–4977. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu Y, Li M, Zhang G, Pang Z. MicroRNA-10b overexpression promotes non-small cell lung cancer cell proliferation and invasion. Eur J Med Res. 2013;18:41. doi: 10.1186/2047-783X-18-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ambros V. The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature. 2004;431:350–355. doi: 10.1038/nature02871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: Genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ni R, Huang Y, Wang J. miR-98 targets ITGB3 to inhibit proliferation, migration, and invasion of non-small-cell lung cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2015;8:2689–2697. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S90998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang P, Wu X, Wang X, Huang W, Feng Q. NEAT1 upregulates EGCG-induced CTR1 to enhance cisplatin sensitivity in lung cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2016;7:43337–43351. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Siragam V, Rutnam ZJ, Yang W, Fang L, Luo L, Yang X, Li M, Deng Z, Qian J, Peng C, et al. MicroRNA miR-98 inhibits tumor angiogenesis and invasion by targeting activin receptor-like kinase-4 and matrix metalloproteinase-11. Oncotarget. 2012;3:1370–1385. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jinushi T, Shibayama Y, Kinoshita I, Oizumi S, Jinushi M, Aota T, Takahashi T, Horita S, Dosaka-Akita H, Iseki K. Low expression levels of microRNA-124-5p correlated with poor prognosis in colorectal cancer via targeting of SMC4. Cancer Med. 2014;3:1544–1552. doi: 10.1002/cam4.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang G, Zhang X, Shi J. MiR-98 inhibits cell proliferation and invasion of non-small cell carcinoma lung cancer by targeting PAK1. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:20135–20145. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen X, Xu Y, Liao X, Liao R, Zhang L, Niu K, Li T, Li D, Chen Z, Duan Y, et al. Plasma miRNAs in predicting radiosensitivity in non-small cell lung cancer. Tumour Biol. 2016;37:11927–11936. doi: 10.1007/s13277-016-5052-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou H, Huang Z, Chen X, Chen S. miR-98 inhibits expression of TWIST to prevent progression of non-small cell lung cancers. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;89:1453–1461. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pasche B, Pennison MJ, Jimenez H, Wang M. TGFBR1 and cancer susceptibility. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2014;125:300–312. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang H, Zhang Q, Wang B, Wu W, Wei J, Li P, Huang R. miR-22 regulates C2C12 myoblast proliferation and differentiation by targeting TGFBR1. Eur J Cell Biol. 2018;97:257–268. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2018.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu F, Chen B, Fan X, Li G, Dong P, Zheng J. Epigenetically-Regulated MicroRNA-9-5p Suppresses the Activation of Hepatic Stellate Cells via TGFBR1 and TGFBR2. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;43:2242–2252. doi: 10.1159/000484303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheng R, Dang R, Zhou Y, Ding M, Hua H. MicroRNA-98 inhibits TGF-β1-induced differentiation and collagen production of cardiac fibroblasts by targeting TGFBR1. Hum Cell. 2017;30:192–200. doi: 10.1007/s13577-017-0163-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosman DS, Phukan S, Huang CC, Pasche B. TGFBR1*6A enhances the migration and invasion of MCF-7 breast cancer cells through RhoA activation. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1319–1328. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou R, Huang Y, Cheng B, Wang Y, Xiong B. TGFBR1*6A is a potential modifier of migration and invasion in colorectal cancer cells. Oncol Lett. 2018;15:3971–3976. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.7725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mody HR, Hung SW, Pathak RK, Griffin J, Cruz-Monserrate Z, Govindarajan R. miR-202 diminishes TGFβ receptors and attenuates TGFβ1-Induced EMT in pancreatic cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2017;15:1029–1039. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-16-0327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee YS, Dutta A. MicroRNAs in cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 2009;4:199–227. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berindan-Neagoe I, Monroig PC, Pasculli B, Calin GA. MicroRNAome genome: A treasure for cancer diagnosis and therapy. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:311–336. doi: 10.3322/caac.21244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Akhurst RJ, Hata A. Targeting the TGFβ signalling pathway in disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012;11:790–811. doi: 10.1038/nrd3810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bierie B, Moses HL. Tumour microenvironment: TGFbeta: the molecular Jekyll and Hyde of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:506–520. doi: 10.1038/nrc1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sethi N, Dai X, Winter CG, Kang Y. Tumor-derived JAGGED1 promotes osteolytic bone metastasis of breast cancer by engaging notch signaling in bone cells. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:192–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kang Y, He W, Tulley S, Gupta GP, Serganova I, Chen CR, Manova-Todorova K, Blasberg R, Gerald WL, Massagué J. Breast cancer bone metastasis mediated by the Smad tumor suppressor pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:13909–13914. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506517102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Attili I, Karachaliou N, Bonanno L, Berenguer J, Bracht J, Codony-Servat J, Codony-Servat C, Ito M, Rosell R. STAT3 as a potential immunotherapy biomarker in oncogene-addicted non-small cell lung cancer. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2018 Apr 2; doi: 10.1177/1758835918763744. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reis H, Metzenmacher M, Goetz M, Savvidou N, Darwiche K, Aigner C, Herold T, Eberhardt WE, Skiba C, Hense J, et al. MET expression in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: Effect on clinical outcomes of chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy. Clin Lung Cancer. 2018;19:e441–e463. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2018.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang H, Yan L, Sun K, Sun X, Zhang X, Cai K, Song T. LncRNA BCAR4 increases viability, invasion and migration non-small cell lung cancer cells by targeting glioma-associated oncogene 2 (GLI2) Oncol Res. 2018 Apr 3; doi: 10.3727/096504018X15220594629967. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ambros V. MicroRNA pathways in flies and worms: Growth, death, fat, stress, and timing. Cell. 2003;113:673–676. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00428-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu W, Xiao P, Wu H, Wang L, Kong D, Yu F. MicroRNA-98 plays a suppressive role in non-small cell lung cancer through inhibition of SALL4 protein expression. Oncol Res. 2017;25:975–988. doi: 10.3727/096504016X14791726591124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 44.Wang MJ, Zhang H, Li J, Zhao HD. microRNA-98 inhibits the proliferation, invasion, migration and promotes apoptosis of breast cancer cells by binding to HMGA2. Biosci Rep. 2018;38:BSR20180571. doi: 10.1042/BSR20180571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 45.Cai C, Huo Q, Wang X, Chen B, Yang Q. SNHG16 contributes to breast cancer cell migration by competitively binding miR-98 with E2F5. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;485:272–278. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.02.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All the data generated or analyzed during this study is included in this published article or are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.