Abstract

Introduction

Schisandrin B (SchB), the main active constituent in Schisandra chinensis, has antioxidant activities. Endothelial dysfunction leads to various cardiovascular diseases. Oxidative stress is a crucial pathophysiological mechanism underpinning endothelial dysfunction.

Methods

We elucidated the role and underlying mechanisms of SchB in angiotensin II-induced rat aortic endothelial-cell deficits and explored targets of SchB through siRNA analysis and molecular docking. We measured apoptosis by TUNEL and oxidative stress by dihydroethidium (DHE) and 2’,7’ –dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCF) staining.

Results

Our results demonstrated that SchB significantly ameliorated oxidative stress, mitochondrial membrane-potential depolarization and apoptosis in angiotensin II-challenged rat aortic endothelial cells. We further discovered that these antioxidative effects of SchB were mediated through induction of Nrf2. Importantly, using molecular docking and molecular dynamic simulation, we identified that Keap1, an adaptor for the degradation of Nrf2, was a target of SchB.

Conclusion

These findings support the potential use of SchB as a Keap1 inhibitor for attenuating oxidative stress, and Keap1 might serve as a therapeutic target in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases.

Keywords: schisandrin B, Keap1, oxidative stress, angiotensin II, rat aortic endothelial cell

Introduction

Vascular endothelial dysfunction is characterized by damage to vascular tone and homeostasis, which leads to various cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), including hypertensive vascular remodeling and ischemic heart disease.1,2 Clinical and experimental studies have shown that dysregulated angiotensin II (AngII), the major effector in the renin–angiotensin system, plays a potential role in vascular injury and endothelial dysfunction.3–5 In addition to its physiological role in arterial blood-pressure regulation including vasoconstriction and retention of sodium and water, AngII directly induces an oxidative stress phenotype in endothelial cells (ECs),6 and leads to mitochondrial dysfunction and EC apoptosis.7,8 As such, an agent targeting AngII-induced endothelial dysfunction may provide a new strategy for the treatment of CVDs.

Among these various functional events involved in CVDs, oxidative stress seems to be upstream of the cascade.9–11 Studies have reported that AngII may be active in cellular oxidation-reduction reactions resulting in the formation of excess free radicals.12,13 The concept that emerges from these observations is that AngII can produce oxidative stress milieu in various tissues, including the vascular endothelium, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction and cell apoptosis.7,8 The crucial roles of oxidative stress in CVDs suggest that molecules with antioxidant properties may enhance the efficacy of treatment protocols designed to mitigate AngII-induced endothelial deficits.

Schisandrin B (SchB), the main active constituent in traditional Chinese medicine derived from Schisandra chinensis,14 has been shown to reduce oxidative stress in various experimental CVD studies, including myocardial infarction,15,16 myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury,17 and doxorubicin-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis.18 Although the mechanisms of these antioxidative activities of SchB are not known, these may at least in part be mediated through the induction of Nrf2 and Nrf2-driven antioxidant responses.19–21 Oxidative stress is intricately related in a positive-feedback mode, not just in endothelial dysfunction but other chronic diseases as well.22 Therefore, amelioration of this central driving factor in endothelial dysfunction by SchB may provide an attractive therapeutic option for CVDs.

In the present study, we evaluated whether SchB was protective against AngII-induced endothelial deficits and explored the underlying mechanisms and targets of SchB. Our results demonstrated that SchB significantly ameliorated cell apoptosis and mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) depolarization in AngII challenged rat aortic ECs (RAECs). SchB also prevented AngII-induced oxidative stress in an Nrf2-dependent manner in RAECs. Importantly, using molecular docking and molecular dynamics (MD) simulation, we identified that Keap1, a negative regulator of Nrf2, was a target of SchB.

Methods

Materials and reagents

SchB and AngII were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). SchB was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) for in vitro experiments. Antibodies against Nrf2 and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). Antibodies against Keap1 were purchased from Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO, USA).

Cell culture and treatment

RAECs were prepared from aortic endothelia of male Sprague Dawley rats (180–200 g; Jiaxing University Animal Center, Jiaxing, China) as described previously.23 All animal care and experimental procedures were in accordance with directives in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (US National Institutes of Health). Animal-care and experimental protocols were approved by the Committee on Animal Care of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Jiaxing University (2018JXSA27). Briefly, rats were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of 1% pentobarbital sodium (40 mg/kg) and sacrificed. Segments of thoracic aortas (18–24 mm) were excised and immediately put in cold Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS). Blood residues in the lumen of the vessels were flushed with HBSS. Collagenase was used to fill the lumen of vessels which were then incubated in HBSS at 37°C for 20 minutes. Effluent from the lumens of vessels was collected and centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 5 minutes. Pellets were washed and suspended in endothelial cell growth medium-2 with 2% FBS at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Experiments were performed on cells at passages 5–8. All dishes were coated with 3% collagen type I (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) during RAEC cultures. Nrf2 or Keap1 gene silencing in cells was achieved by transfecting cells with siRNA (5′-GGGAGGAGCUAUUAUCCAUTT-3′ for Nrf2, 5′-GUCCUGCACAACUGUAUCUTT-3′ for Keap1) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Knockdown was verified by Western blotting.

Schisandrin B-viability test

Cell viability was assessed following SchB exposure by MTT assay. Cells were plated in 96-well plates at 5,000 cells per well and treated with SchB at different concentrations (2.5, 5, 10, 20, 40, 60, and 80 µM) for 72 hours. Cell viability was calculated as Atreated/Acontrol ×100%.

TUNEL staining

TUNEL staining was performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded cells with an apoptosis-detection kit (C1086; Beyotime, Haimen, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Positively stained apoptotic cells were counted in at least five random microscopic fields belonging to each experimental group. Percentages of TUNEL positive cells relative to each group are presented. (200× amplification; Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

Determination of MMP

Cells were cultured as indicated and MMP determined by 5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethyl-imidacarbocyanine iodide (JC1) dye. JC1 selectively enters mitochondria and reversibly changes from green to red as the MMP increases. In healthy cells with high MMP (Δψm), JC1 spontaneously forms J-aggregates with intense red fluorescence. Low Δψm in apoptotic cells maintains JC1 in the monomeric form, and shows only green fluorescence. JC1 fluorescence images of cells exposed to high glucose with or without schisandrin B pretreatment were captured using fluorescence microscopy (400× amplification; Nikon).

Determination of ROS generation in cells

Cells were exposed to AngII with or without pretreatment with different concentrations of SchB. Pretreatment was carried out for 1 hour. To analyze ROS generation, various subtypes of ROS, such as superoxide (O2−) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), were detected using 5 µM dihydroethidium (DHE) and 2 µM 2’,7’ –dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCF), respectively, as described previously.23 Cellular images were captured under fluorescence microscopy (200× amplification; Nikon).

Real-time quantitative PCR

Total RNA was isolated from cells using Trizol (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Reverse-transcription and quantitative PCR (qPCR) were carried out with a two-step Platinum SYBR green qPCR SuperMix UDG kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Mastercycler (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) was used for qPCR analysis. Primers were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (sequences listed in Table 1). Target mRNA was normalized to β-actin.

Table 1.

Sequences of primers for real-time qPCR assay used in the study

| Gene | Species | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nrf2 | Rat | ACTGTCCCCAGCCCAGAGGC | CCAGGCGGTGGGTCTCCGTA |

| Ho1 | Rat | TCTATCGTGCTCGCATGAAC | CAGCTCCTCAAACAGCTCAA |

| Nqo1 | Rat | ACCTTGCTTTCCATCACCAC | CAAAGGCGAAAACTGAAAGC |

| Actb | Rat | AAGTCCCTCACCCTCCCAAAAG | AAGCAATGCTGTCACCTTCCC |

Western blotting and coimmunoprecipitation

Cells were lysed and protein amounts determined by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad). Proteins were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and electrotransferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Each membrane was blocked for 1.5 hours with Tris-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween 20 and 5% nonfat milk. Membranes were then incubated with specific primary antibodies. Immunoreactive bands were detected by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies and visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (Bio-Rad). Protein quantities were analyzed using ImageJ software version 1.38e and normalized to their respective controls. For immunoprecipitation studies, extracts were incubated with anti-Keap1 antibody for 4 hours and then precipitated with protein G Sepharose beads at 4°C overnight. Nrf2 and Keap1 levels were detected by immunoblotting using specific antibodies.

Construction of initial structure of Keap1–SchB complex

The crystal structure of Keap1 was obtained from the Protein Data Bank (5CGJ).24 The structure of Keap1 was preprocessed by UCSF Chimera 1.12 software, including removal of all water molecules and heteroatoms, with missing hydrogen atoms added. The AutoDock 4.2.6 software package was used to predicted the binding mode between Keap1 and SchB.25 Prior to molecular docking, Keap1 and SchB were processed by AutoDock Tools 1.5.6 software, and a grid box of 22.5×22.5×22.5 Å was selected and covered the entire active binding site of Keap1. The Lamarckian genetic algorithm was utilized for global conformational sampling with trials of 200 dockings, and other parameters were set as default. The lowest predicted binding-energy conformation was selected for MD-simulation analysis.

MD simulation

The standard ff14SB force field and general amber force field 2 were applied to describe the parameters of Keap1 and SchB, respectively.26 The complex was then immersed into a box of TIP3P water molecules with at least 12 Å distance around the complex and seven sodium ions added to maintain electroneutrality. Afterward, a two-step energy-minimization strategy was carried out. Firstly, 5,000 cycles of the steepest descent and 5,000 cycles of conjugate-gradient minimizations with a 5 kcal⋅mol−1⋅Å−2 restraint on the Cα of Keap1, then 2,500 cycles of the steepest descent and 2,500 cycles of conjugate-gradient minimizations without any restraint were carried out. Thereafter, the system was heated from 0 to 310 K within 200 ps with a 2 kcal⋅mol−1⋅Å−2 restraint on the protein. Subsequently, the density procedure was performed at 310 K for 200 ps and equilibration at 310 K for 200 ps in an isothermal isobaric (NPT) ensemble. Finally, 200 ns MD simulation was carried out in the NPT ensemble. During productive MD simulations, covalent bonds between heavy atoms and hydrogen atoms were constrained using the SHAKE algorithm. The particle-mesh Ewald algorithm was used to calculate long-range electrostatic interactions. Coordinates were saved every 8 ps for further analysis. Binding free-energy decomposition was calculated using molecular mechanics/generalized Born surface-area method. The modified generalized Boltzmann model of 2 was applied,27 and 100 snapshots were extracted from the last 40 ns of MD trajectory for the binding free-energy calculations as described previously.28

Statistical analysis

All data represent at least three independent experiments and are expressed as median and ranges. The sample size of each group was three to five. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 20.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Kruskal–Wallis test or Mann–Whitney U test was employed to analyze differences between sets of data. P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

SchB inhibited AngII-induced apoptosis and MMP depolarization in RAECs

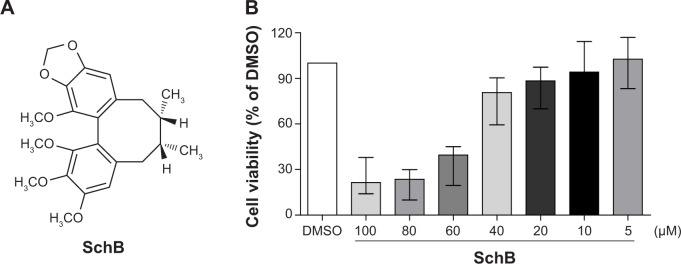

The chemical structure of SchB is shown in Figure 1A. We initially determined the effect of SchB on cell viability. As shown in Figure 1B, SchB significantly inhibited cell proliferation at concentrations of 40 µM for RAECs (80.62% [59.43%–90.39%]) compared to the DMSO group (100%). Therefore, we selected 10 and 20 µM for our study.

Figure 1.

The chemical structure of Sch B and the effect of Sch B on cell viability.

Notes: (A) Chemical structure of SchB. (B) Rat aortic endothelial cells were treated with SchB at indicated concentrations for 72 hours and then tested for any potential effect of SchB on viability by MTT assay.

Abbreviations: DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; SchB, schisandrin B.

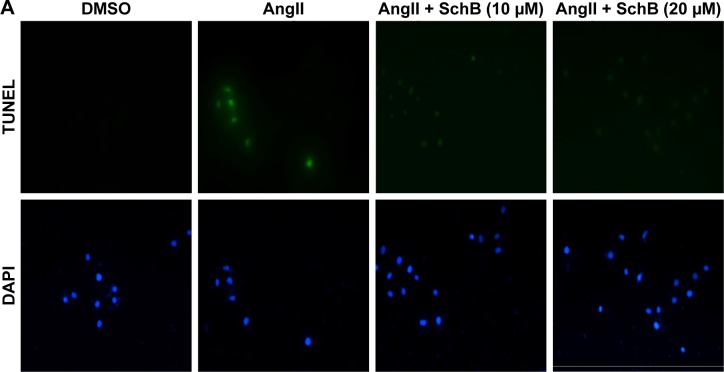

Studies have shown that endothelial dysfunction is closely associated with cell apoptosis.8 To determine the protective effects of SchB on EC apoptosis, we utilized TUNEL staining. RAECs from the AngII group showed increased TUNEL-positive apoptotic ECs (27.53% [19.64%–31.62%]) compared to the DMSO group (2% [1%–3%]; Figure 2A and B). However, treatment with SchB at either 10 (15.73% [10.23%–16.97%]) or 20 (8.125% [6.225%–11.97%]) µM prevented this increase (Figure 2A and B). Previous research has shown that MMP depolarization plays an essential role in AngII-induced apoptosis of ECs.7 This antiapoptosis response by SchB was also associated with reduced perturbation of mitochrondrial dysfunction in RAECs exposed to AngII. JC1 is a cell-permeable cationic dye that accumulates in mitochondria and yields green (low concentrations) and red (high concentrations) fluorescence. JC1 produced red fluorescence in cells with high MMP, clearly showing preservation of mitochondrial function in cells treated with SchB compared to the AngII group (1.025 [0.8937–1.051] vs 0.6225 [0.5275–0.6425]; P<0.05; Figure 2C and D).

Figure 2.

SchB inhibited AngII-induced apoptosis and MMP depolarization in RAECs.

Notes: RAECs were pretreated with SchB (10 or 20 µM) for 1 hour and then incubated with AngII (1 µM) for the times indicated. After exposure to AngII for 24 hours, the effect of SchB on AngII-induced apoptosis in RAECs was determined by TUNEL staining. Representative images for TUNEL staining are shown (A), with quantitative columns for TUNEL-positive cells (B). (C) Effect of SchB on prevention of AngII-induced mitochondrial dysfunction was assessed by JC1 staining. Increased green and reduced red fluorescence in the AngII group (24 hours’ exposure) is indicative of MMP alteration. This alteration was normalized in cells treated with SchB. (D) Quantitative analysis of the ratio of red:green fluorescence (*P<0.05 compared to DMSO; #P<0.05 compared to AngII). Magnification: 200× amplification (A); 400× amplification (C).

Abbreviations: AngII, angiotensin II; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; MMP, mitochondrial membrane potential; RAECs, rat aortic endothelial cells; SchB, schisandrin B.

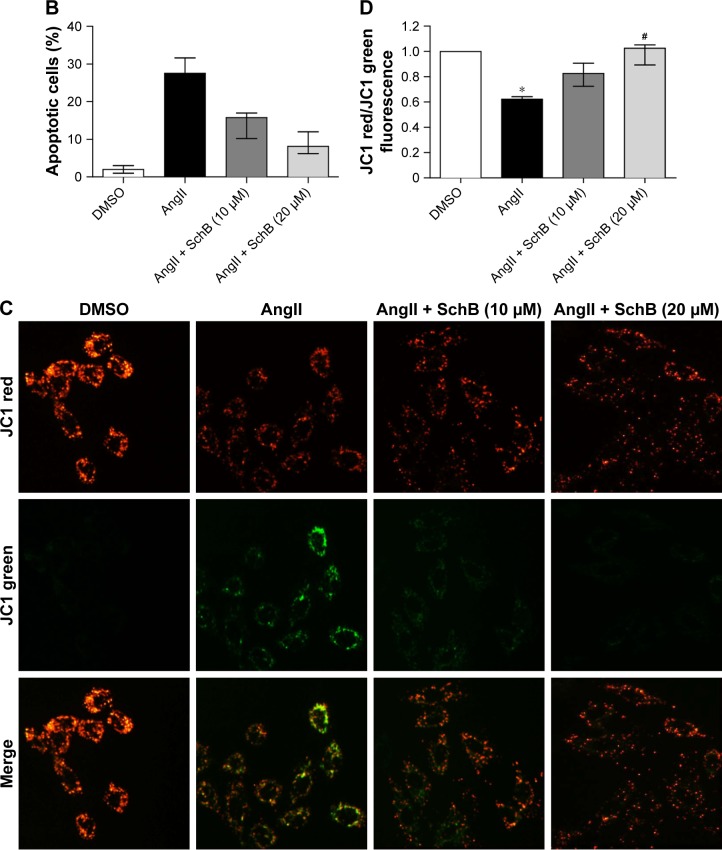

SchB inhibited AngII-induced ROS generation and induced antioxidant response in RAECs

Oxidative stress seems to be upstream of the cascade of various functional events, such as apoptosis and mitochondrial dysfunction in CVDs.9–11 As such, we examined the direct effects of SchB on AngII-induced oxidative stress in RAECs. To analyze ROS generation in RAECs, we utilized two assays. First, we stained the RAECs with DCF (Figure 3A and B). We then stained RAECs with DHE (Figure 3C and D). Both measures showed increased oxidative stress levels in AngII-induced RAECs compared to the DMSO group (4.623 [2.528–5.643] vs 1, P<0.05 for DCF; 7.623 [5.643–8.557] vs 1, P<0.01 for DHE; Figure 3A–D). Treatment with SchB dose-dependently decreased ROS production in AngII-stimulated RAECs (1.973 [1.125–2.225] vs 4.623 [2.528–5.643], P<0.05 for DCF; 1.782 [1.245–1.976] vs 7.623 [5.643–8.557], P<0.01 for DHE; Figure 3A–D).

Figure 3.

SchB inhibited AngII-induced ROS generation and induced antioxidant responses in RAECs.

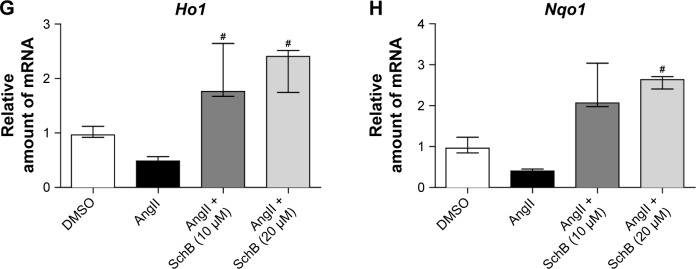

Notes: RAECs were pretreated with SchB (10 or 20 µM) for 1 hour and then incubated with AngII (1 µM) for the times indicated. After exposure to AngII for 12 hours, the effect of SchB on AngII-induced ROS generation in RAECs was determined by DCF (A) and DHE (C) staining, followed by semiquantitative analysis (B, D). DCF was rapidly deacetylated by cellular esterases and then oxidized in the presence of ROS into fluorescent DCF. DHE formed a red fluorescent product (ethidium) upon reaction with superoxide anions and intercalated with DNA. (E) Exposure to AngII for 8 hours. SchB induced an antioxidant response in RAECs, as evidenced by increased protein levels of Nrf2. GAPDH was used as loading control. (F–H) Exposure to AngII for 6 hours. mRNA expression of Nrf2 (F), Ho1 (G), and Nqo1 (H) was assessed in RAECs. mRNA levels were normalized to β-actin, and are shown relative to DMSO. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 compared to DMSO; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01 compared to AngII. Magnification: 200× amplification (A and C).

Abbreviations: AngII, angiotensin II; DHE, dihydroethidium; DCF, 2’,7’ –dichlorofluorescin diacetate; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; RAECs, rat aortic endothelial cells; SchB, schisandrin B.

These findings are in alignment with previous reports of SchB inhibiting ROS generation in LPS/ATP-challenged peritoneal macrophages29 and mitogen-stimulated lymphocytes.19 Those studies further showed that SchB may mediate this antioxidant activity through induction of Nrf2 and its downstream antioxidant-response genes.19,29 To determine whether the same mechanism was reducing AngII-induced oxidative injury in RAECs, we assessed Nrf2 and Nrf2-driven HO1 and NQO1. Our data showed that protein and mRNA levels of Nrf2 were all significantly induced in a dose-dependent manner when AngII-challenged cells were treated with SchB (2.598 [2.399–3.396] vs 0.9694 [0.8858–0.9820], P<0.01 for protein; 2.895 [2.587–3.411] vs 0.6181 [0.5695–0.6863], P<0.05 for mRNA; Figure 3E–F). Consistently with Nrf2 activation, mRNA levels of Ho1 (2.408 [1.746–2.517] vs 0.4874 [0.2183–0.5642], P<0.05; Figure 3G) and Nqo1 (2.636 [2.367–2.749] vs 0.4037 [0.3119–0.4531], P<0.05; Figure 3H) were also upregulated in AngII-stimulated RAECs by pretreatment with SchB (10 and 20 µM) compared to the AngII group.

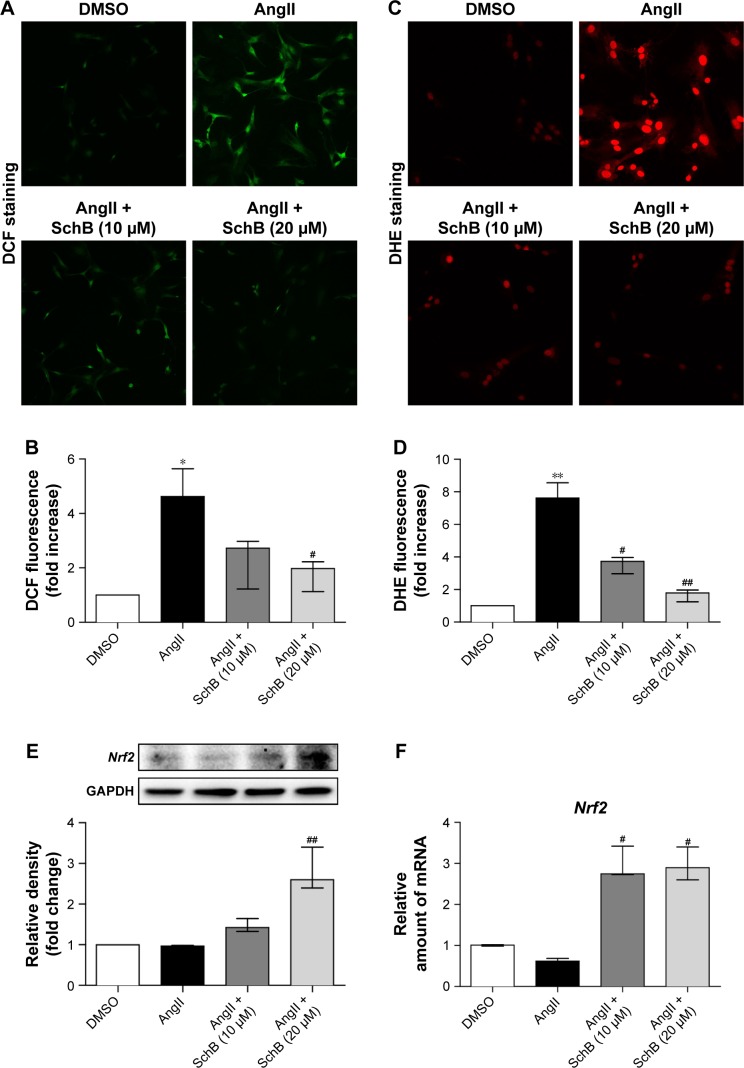

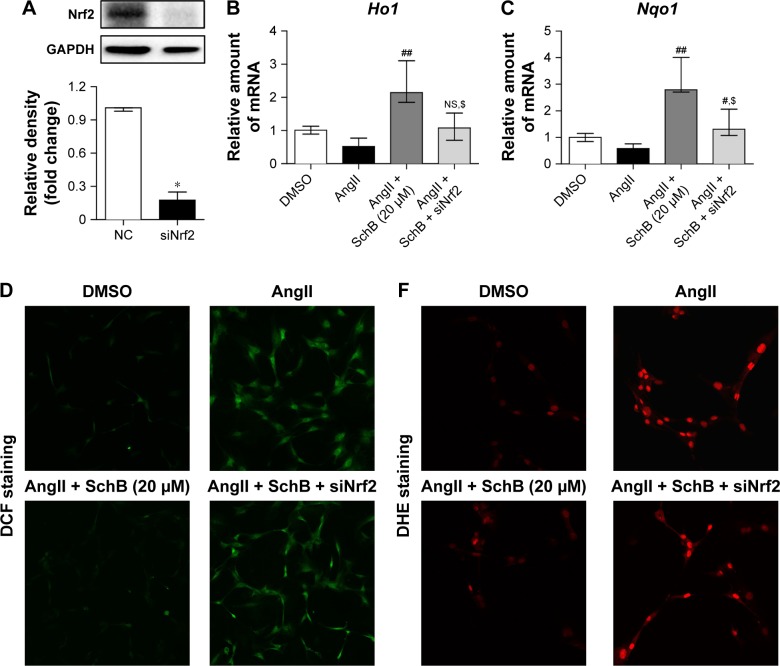

Antioxidant activities of SchB involved modulation of Keap1–Nrf2 pathway

To provide further support for the role of Nrf2 in regulating the antioxidant effects of SchB in AngII-challenged RAECs, we knocked down the expression of Nrf2 prior to AngII exposure. Transfection of cells with specific siRNA reduced protein abundance by >80% compared to the negative control group (0.1764 [0.1314–0.2494] vs 1.010 [0.9800–1.010], P<0.05; Figure 4A). SchB treatment significantly upregulate Ho1 (2.143 [1.852–3.101] vs 0.5169 [0.2851–0.7731], P<0.01; Figure 4B) and Nqo1 (2.792 [2.703–4.005] vs 0.5780 [0.08920–0.7568], P<0.01; Figure 4C) mRNA levels in normalizing AngII-induced RAECs, while SchB was not able to induce these genes in Nrf2-knockdown RAECs challenged by AngII compared to the AngII + SchB group (1.077 [0.7071–1.526] vs 2.143 [1.852–3.101], P<0.05 for Ho1; 1.302 [1.071–2.062] vs 2.792 [2.703–4.005], P<0.05 for Nqo1; Figure 4B–C). SchB was not able to inhibit ROS generation, including H2O2 (3.747 [3.540–4.128] vs 1.211 [1.155–1.328], P<0.05; Figure 4D and E) and O2− (5.473 [4.259–6.931] vs 1.840 [1.349–2.983], P<0.05; Figure 4F and G), in AngII-stimulated Nrf2-knockdown RAECs compared to the AngII + SchB group. These results suggest that the antioxidant activities of SchB were Nrf2-dependent in AngII-induced RAECs.

Figure 4.

Antioxidant effects of SchB involved modulation of the Keap1–Nrf2 pathway.

Notes: (A) Western blot analysis of Nrf2 following siRNA transfection in RAECs. *P<0.05 compared to NC. RAECs were pretreated with SchB (20 µM) for 1 hour and then incubated with AngII (1 µM) for the times indicated. (B, C) After exposure to AngII for 6 hours, RT-qPCR detected the effect of Nrf2 knockdown on AngII-induced Ho1 (B) and Nqo1 (C) mRNA levels. After exposure to AngII for 12 hours, the effect of Nrf2 knockdown on AngII-induced ROS generation was determined by DCF (D) and DHE (F) staining, followed by semiquantitative analysis (E, G). (H) SchB reduced interaction between Nrf2 and Keap1. RAECs were pretreated with SchB (10 or 20 µM) for 1 hour and then incubated with AngII (1 µM) for 30 minutes. Lysates were then subjected to Keap1 IP and Nrf2 measured. (I) Western blot analysis of Keap1 following siRNA transfection in RAECs. (J) IB analysis of Nrf2 following Keap1 knockdown. RAECs transfected with negative control or Keap1 siRNA were treated with SchB for 1 hour before 8 hours’ AngII stimulation. GAPDH used as loading control. *P<0.05 compared to DMSO; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01 compared to AngII; $P<0.05 compared to AngII + SchB. Magnification: 200× amplification (D and F).

Abbreviations: AngII, angiotensin II; DHE, dihydroethidium; DCF, 2’,7’ –dichlorofluorescin diacetate; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; NS, not significant (compared to AngII); IB, immunoblot; IP, immunoprecipitation; NC, negative control; RAECs, rat aortic endothelial cells; RT, reverse transcription; SchB, schisandrin B.

Under normal conditions, Nrf2 is retained inactivated in the cytoplasm by binding with its inhibitor Keap1, which serves as an adaptor for the degradation of Nrf2. Previous research has indicated the potential interaction of small-molecular inhibitor with Nrf2-binding sites in the Keap1 protein.30–32 As such, we reasoned that SchB potentially acts on the Keap1 protein. To test this possibility, we assessed Nrf2–Keap1 complex formation in the context of SchB. Coimmunoprecipitation showed that Nrf2 was located in Keap1 in the DMSO and AngII groups, while SchB treatment of RAECs remarkably decreased the recruitment of Nrf2 to Keap1 (Figure 4H). We then transfected RAECs with Keap1-targeting siRNA (Figure 4I). SchB treatment (1.910 [1.768–2.195] vs 0.9250 [0.7924–1.214], P<0.05) or knockdown of Keap1 (1.634 [1.386–1.978] vs 0.9250 [0.7924–1.214]) upregulated Nrf2 compared to the AngII group. Pretreatment of SchB in siRNA-transfected cells showed further induction in Nrf2 levels compared to the AngII + SchB group (2.550 [2.456–2.680] vs 1.910 [1.768–2.195], P<0.05; Figure 4J). The potentiation of SchB activity in cells transfected with Keap1 siRNA suggested that SchB engaged Keap1 in inducing Nrf2 in AngII-stimulated RAECs.

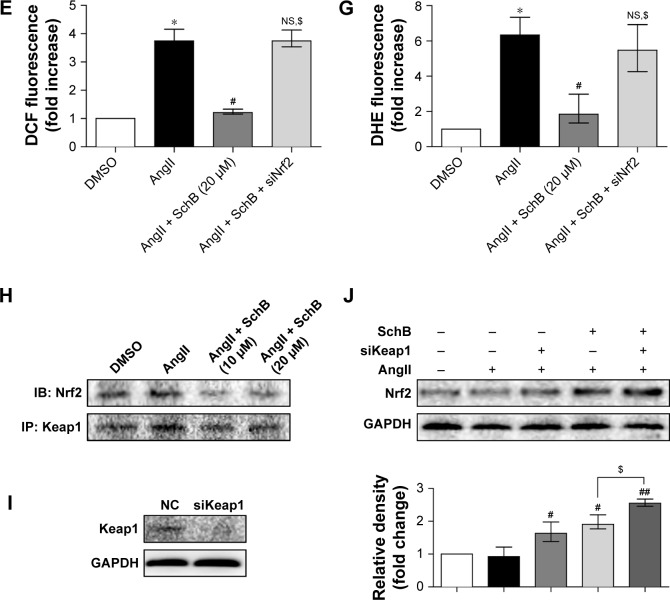

Keap1 may be the target of SchB in producing an antioxidant phenotype

To investigate the binding mode of SchB to Keap1, molecular docking and MD simulation were carried out. Root-mean SD of backbone atoms (Cα) of Keap1 and heavy atoms of SchB were used to monitor the dynamic stability of the Keap1–SchB complex. As shown in Figure 5A, root-mean SD values of the backbone atoms of Keap1 and the heavy atoms of SchB had small fluctuations during the whole MD simulation. These findings suggested that SchB underwent minor adjustments compared with the docking conformation, which is consistent with the induced-fit theory. In addition, pairwise correlations in the motions of the residues averaged the MD-simulation trajectory were calculated by dynamic cross-correlation analysis (Figure 5B). Positive regions (red) represent correlated motions between residues, whereas negative regions (dark blue) represent anticorrelation motions of specific residues. As shown in Figure 5B, besides the diagonal regions that represent correlation/anticorrelation between residues and their own, correlative motions in most regions showed relatively low correlation/anticorrelation motions, indicating the Keap1–SchB complex was relatively stable during simulation.

Figure 5.

Structural and energetic analysis of SchB to the binding site of Keap1 by MD simulation.

Notes: (A) RMSD curves for the 200 ns MD simulation. (B) Dynamic cross-correlations of residue fluctuations from MD simulations. (C) Per residue contribution of binding energy of the Keap1–SchB complex. To get a clear view, only residues in the top ten contributed are shown. (D) Structural analysis of the ten most contributed residues of Keap1 to SchB.

Abbreviations: MD, molecular dynamics; RMSD, root-mean SD; SchB, schisandrin B.

Then, binding free energies were decomposed into contributions of each residue to understand the roles of individual residues in determining the interaction between Keap1 and SchB. Herein, a plot (Figure 5C and D) showing binding free-energy contributions of each amino acid was calculated. As illustrated in Figure 5C, the ten key residues contributing most were Tyr334, Arg415, Ile461, Phe478, Arg483, Ser508, Gly509, Tyr525, Ala556, Tyr572. Predominant interactions were hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions. Nrf2 was inserted into the hydrophobic region of the Keap1 pocket.33 Our results show that SchB forming multiple hydrophobic interactions with Keap1 may explain the inhibition of SchB against Keap1 binding Nrf2.

Discussion

Vascular endothelial dysfunction is one of the most common complications in CVDs, wherein damage to ECs is an early feature of vessel-wall injury. Emerging evidence has shown that AngII plays a direct role in EC injury and function change.5 Key findings of our study include SchB, a natural compound in traditional Chinese medicine using S. chinensis, preventing AngII-induced oxidative stress and subsequent cell apoptosis and MMP depolarization in RAECs. We then discovered that these antioxidative effects of SchB were mediated through the induction of Nrf2. We also found that SchB targeted Keap1, a negative regulator of Nrf2, and the stable binding of Keap1 to SchB may have occupied a portion of Nrf2.

The role of AngII in many CVDs, including hypertensive vascular deficits and cardiac hypertrophy, is well established. Early in heart failure, AngII is activated as a compensatory mechanism. However, with progression of the disease, the system and its activity become detrimental and are responsible for generating the hallmarks of clinical heart failure. AngII is known to be elevated in patients with CVDs. In addition to its physiological role in arterial blood-pressure regulation, including vasoconstriction and retention of sodium and water, AngII directly induces vascular endothelial dysfunction through various functional events through activating inflammation, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and EC apoptosis.7,8 Therefore, we applied AngII-induced endothelial deficits to evaluate endothelial function. One of the effects of AngII in the vascular endothelium was excessive generation of ROS, which leads to oxidative stress.34 Increased oxidative stress can further affect EC viability and impair endothelium-dependent relaxation.35 However, despite this enhanced knowledge on the pathogenesis, treatment options for endothelial dysfunction are ineffective and limited. In our study, we found that SchB significantly attenuated AngII-induced oxidative stress in RAECs (Figure 3A–D). Consistently with previous reports,19–21 there was induction of Nrf2 and Nrf2-driven antioxidant response genes when cells were exposed to SchB (Figure 3E–H).

We then focused our study on potential antioxidant mechanisms of SchB. It is now well established that SchB induces Nrf2 and Nrf2-driven antioxidant-response genes.19–21 Our result showed that SchB was not able to induce HO1 or NQO1 or inhibit ROS generation, including H2O2 and O2− in AngII-stimulated Nrf2-knockdown RAECs (Figure 4). The concept that emerges from these observations is that SchB prevents AngII-induced oxidative stress in an Nrf2-dependent mechanism. As such, there is a pressing need to understand how SchB activates Nrf2 signaling and the binding target of SchB. In general, Nrf2 exists in the cytoplasm by binding with its inhibitor, Keap1, which serves as an adaptor for the degradation of Nrf2. Once exposed to stressors or inducers, the conformation of Keap1 changes and then Nrf2 separates from Keap1 and translocates into the nucleus to promote the expression of its downstream antioxidant genes, such as Ho1 and Nqo1. Increasing evidence has demonstrated that the Nrf2–Keap1 signaling pathway plays important roles in maintaining the balance of cellular redox homeostasis, and has become a vital target for the prevention and treatment of oxidative stress-related diseases.30–32 To test the intracellular localization and translocation of Keap1 and Nrf2, we assessed Nrf2–Keap1 complex formation in the context of SchB by coimmunoprecipitation. As shown in Figure 4H, SchB treatment of RAECs remarkably decreased the recruitment of Nrf2 to Keap1. To verify that SchB attenuated AngII-induced oxidative stress by targeting Keap1, we transfected RAECs with Keap1-targeting siRNA. SchB treatment or knockdown of Keap1 upregulated Nrf2. Pretreatment of SchB in siRNA-transfected cells showed further inductions in levels of Nrf2 (Figure 4J). Potentiation of SchB activity in cells transfected with Keap1 siRNA suggested that SchB engaged Keap1 in inducing Nrf2 in AngII-stimulated RAECs.

SchB has been shown to regulate many biological functions and signaling pathways. To our knowledge, we have shown for the first time direct SchB binding. Using conventional MD simulation, we found reasonable binding conformation of the Keap1–SchB complex and the ten key residues contributing most were Tyr334, Arg415, Ile461, Phe478, Arg483, Ser508, Gly509, Tyr525, Ala556, Tyr572 (Figure 5). Predominant interactions were hydrogen-bond and hydrophobic interactions. A previous study reported that Nrf2 was inserted into the hydrophobic region of the Keap1 pocket.33 These docking results showed that SchB formed multiple hydrophobic interactions with Keap1, and may explain the competition and inhibition of SchB against Keap1-binding Nrf2. Overall, the comprehensive simulation methods in this study verified that Keap1 may be the target of SchB in producing an antioxidant phenotype. The possibility that SchB targets the Keap1–Nrf2 complex is intriguing as it may identify a new mechanism of SchB-induced protective effects in ECs.

It is well known that oxidative stress in cells is strongly associated with the induction of apoptosis.9–11 An in vitro study revealed that SchB protected H9C2 cells against apoptosis through inhibition of ROS production.21 We showed that RAECs underwent apoptosis as the result of oxidative damage, which was evidenced by the enhanced number of apoptotic cells (Figure 2A and B). These findings prove the antiapoptosis activity of SchB in AngII-induced endothelial injury. Also, MMP depolarization played an essential role in the AngII-induced apoptosis of ECs.7 Our results showed that SchB significantly ameliorated MMP depolarization in AngII-challenged RAECs (Figure 2C and D).

The main limitation of this study is the small sample. As basic research, at least three independent experiments were performed. The sample size of each group was three to five. It is extremely difficult to test data distribution with such a small sample. Therefore, nonparametric tests (Kruskal– Wallis or Mann–Whitney) were employed to analyze the differences between sets of data. All data are expressed as medians and range. Nonparametric tests are recommended for small samples when it is not possible to test distribution, but their power and accuracy is inferior to parametric tests.

Overall, this work shows that a novel mechanism of SchB, a dibenzocyclooctadiene derivative of S. chinensis, targeted Keap1 and attenuated AngII-stimulated oxidative stress and subsequent apoptosis and MMP depolarization in RAECs. SchB bound to Keap1, an adaptor for the degradation of Nrf2, and occupied multiple hydrophobic portions of Nrf2. Then, Nrf2 promoted the expression of its downstream antioxidant genes Ho1 and Nqo1. These findings also support the concept that Keap1 might serve as a therapeutic target in the treatment of CVDs.

Data availability

All data herein are available from the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Public Welfare Science and Technology Program of Jiaxing City (grant no 2018AY32008; Jiaxing China).

Footnotes

Author contributions

XS, JH, ZZ, BZ, and FS performed the research. JH, XS, JX, and LJ designed the study. JH and LJ contributed essential reagents or tools. JH, XS, ZZ, and BZ analyzed the data. JH, JX, and LJ wrote the paper. All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting and revising the article, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Wallace SM, Yasmin, Mceniery CM, et al. Isolated systolic hypertension is characterized by increased aortic stiffness and endothelial dysfunction. Hypertension. 2007;50(1):228–233. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.089391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellien J, Remy-Jouet I, Iacob M, et al. Impaired role of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids in the regulation of basal conduit artery diameter during essential hypertension. Hypertension. 2012;60(6):1415–1421. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.201087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suzuki R, Fukuda N, Katakawa M, et al. Effects of an angiotensin II receptor blocker on the impaired function of endothelial progenitor cells in patients with essential hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27(5):695–701. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpt208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamamoto E, Kataoka K, Shintaku H, et al. Novel mechanism and role of angiotensin II induced vascular endothelial injury in hypertensive diastolic heart failure. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27(12):2569–2575. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.153692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suzuki H, Kimura K, Shirai H, et al. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase inhibits G12/13 and rho-kinase activated by the angiotensin II type-1 receptor: implication in vascular migration. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29(2):217–224. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.181024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kröller-Schön S, Daiber A, Steven S, et al. Crucial role for Nox2 and sleep deprivation in aircraft noise-induced vascular and cerebral oxidative stress, inflammation, and gene regulation. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(38):3528–3539. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang Y, Li Y, Ye N, et al. Atorvastatin inhibits the apoptosis of human umbilical vein endothelial cells induced by angiotensin II via the lysosomal-mitochondrial axis. Apoptosis. 2016;21(9):977–996. doi: 10.1007/s10495-016-1271-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu Y, Wang RH, Guo BB, Jia YP. Quercetin inhibits angiotensin II induced apoptosis via mitochondrial pathway in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2016;20(8):1609–1616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Förstermann U, Xia N, Li H. Roles of vascular oxidative stress and nitric oxide in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2017;120(4):713–735. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.309326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McSweeney SR, Warabi E, Siow RC. Nrf2 as an Endothelial mechano-sensitive transcription factor: going with the flow. Hypertension. 2016;67(1):20–29. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.06146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Münzel T, Camici GG, Maack C, Bonetti NR, Fuster V, Kovacic JC. Impact of oxidative stress on the heart and vasculature: part 2 of a 3-part series. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(2):212–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.05.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsu HH, Hoffmann S, Di Marco GS, et al. Downregulation of the antioxidant protein peroxiredoxin 2 contributes to angiotensin II-mediated podocyte apoptosis. Kidney Int. 2011;80(9):959–969. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh VP, Le B, Khode R, Baker KM, Kumar R. Intracellular angiotensin II production in diabetic rats is correlated with cardiomyocyte apoptosis, oxidative stress, and cardiac fibrosis. Diabetes. 2008;57(12):3297–3306. doi: 10.2337/db08-0805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hancke JL, Burgos RA, Ahumada F. Schisandra chinensis (Turcz.) Baill. Fitoterapia. 1999;70(5):451–471. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen P, Pang S, Yang N, et al. Beneficial effects of schisandrin B on the cardiac function in mice model of myocardial infarction. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chun JN, Cho M, So I, Jeon JH. The protective effects of Schisandra chinensis fruit extract and its lignans against cardiovascular disease: a review of the molecular mechanisms. Fitoterapia. 2014;97:224–233. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2014.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yim TK, Ko KM, Km K. Methylenedioxy group and cyclooctadiene ring as structural determinants of schisandrin in protecting against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats. Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;57(1):77–81. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(98)00297-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thandavarayan RA, Giridharan VV, Arumugam S, et al. Schisandrin B prevents doxorubicin induced cardiac dysfunction by modulation of DNA damage, oxidative stress and inflammation through inhibition of MAPK/p53 signaling. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0119214. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Checker R, Patwardhan RS, Sharma D, et al. Schisandrin B exhibits anti-inflammatory activity through modulation of the redox-sensitive transcription factors Nrf2 and NF-κB. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;53(7):1421–1430. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwan HY, Niu X, Dai W, et al. Lipidomic-based investigation into the regulatory effect of Schisandrin B on palmitic acid level in non-alcoholic steatotic livers. Sci Rep. 2015;5:9114. doi: 10.1038/srep09114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chiu PY, Chen N, Leong PK, Leung HY, Ko KM. Schisandrin B elicits a glutathione antioxidant response and protects against apoptosis via the redox-sensitive ERK/Nrf2 pathway in H9c2 cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2011;350(1–2):237–250. doi: 10.1007/s11010-010-0703-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nishida K, Otsu K. Inflammation and metabolic cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Res. 2017;113(4):389–398. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvx012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang L, Han J, Shan P, et al. MD2 blockage protects obesity-induced vascular remodeling via activating AMPK/Nrf2. Obesity. 2017;25(9):1532–1539. doi: 10.1002/oby.21916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Winkel AF, Engel CK, Margerie D, et al. Characterization of RA839, a noncovalent small molecule binder to keap1 and selective activator of Nrf2 signaling. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(47):28446–28455. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.678136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morris GM, Huey R, Lindstrom W, et al. AutoDock4 and AutoDock-Tools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J Comput Chem. 2009;30(16):2785–2791. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maier JA, Martinez C, Kasavajhala K, Wickstrom L, Hauser KE, Simmerling C. Ff14SB: improving the accuracy of protein side chain and backbone parameters from ff99SB. J Chem Theory Comput. 2015;11(8):3696–3713. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller BR, McGee TD, Swails JM, Homeyer N, Gohlke H, Roitberg AE. MMPBSA.py: An efficient program for end-state free energy calculations. J Chem Theory Comput. 2012;8(9):3314–3321. doi: 10.1021/ct300418h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tang X, Wang Z, Lei T, Zhou W, Chang S, Li D. Importance of protein flexibility on molecular recognition: modeling binding mechanisms of aminopyrazine inhibitors to Nek2. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2018;20(8):5591–5605. doi: 10.1039/c7cp07588j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leong PK, Ko KM, Km K. Schisandrin B induces an Nrf2-mediated thioredoxin expression and suppresses the activation of inflammasome in vitro and in vivo. Biofactors. 2015;41(5):314–323. doi: 10.1002/biof.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marcotte D, Zeng W, Hus JC, et al. Small molecules inhibit the interaction of Nrf2 and the Keap1 Kelch domain through a non-covalent mechanism. Bioorg Med Chem. 2013;21(14):4011–4019. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramar V, Pappu S. Exploring the inhibitory potential of bioactive compound from Luffa acutangula against NF-κB-A molecular docking and dynamics approach. Comput Biol Chem. 2016;62:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2016.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pang C, Zheng Z, Shi L, et al. Caffeic acid prevents acetaminophen-induced liver injury by activating the Keap1-Nrf2 antioxidative defense system. Free Radic Biol Med. 2016;91:236–246. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suzuki T, Yamamoto M. Molecular basis of the Keap1-Nrf2 system. Free Radic Biol Med. 2015;88(Pt B):93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maleszewska M, Moonen JR, Huijkman N, van de Sluis B, Krenning G, Harmsen MC. IL-1β and TGFβ2 synergistically induce endothelial to mesenchymal transition in an NFκB-dependent manner. Immunobiology. 2013;218(4):443–454. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2012.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Touyz RM. Reactive oxygen species and angiotensin II signaling in vascular cells – implications in cardiovascular disease. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2004;37(8):1263–1273. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2004000800018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data herein are available from the authors on request.