Significance

Heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) molecular chaperones act as a central hub of cellular proteostasis network. The functions of Hsp70s rely on allosteric communication between nucleotide-binding domain and substrate-binding domain. Current mechanistic models for Hsp70 allostery are based on extensive study of the bacterial Hsp70, DnaK. Here, we report that the allosteric landscapes of the eukaryotic cytoplasmic Hsp70s, HspA1 and Hsc70, diverge significantly from that of DnaK in that they favor a domain-docked, low substrate-affinity state much more than DnaK does. Our mutational results illustrate how this evolutionary tunability of Hsp70s arises by modulation of key allosteric interfaces. These insights will help in understanding the mechanism of Hsp70 functional diversities and aid in the design of small-molecule modulators of Hsp70s.

Keywords: Hsp70, methyl-TROSY NMR, allostery, chaperone

Abstract

The 70-kDa heat shock proteins (Hsp70s) are molecular chaperones that perform a wide range of critical cellular functions. They assist in the folding of newly synthesized proteins, facilitate assembly of specific protein complexes, shepherd proteins across membranes, and prevent protein misfolding and aggregation. Hsp70s perform these functions by a conserved mechanism that relies on allosteric cycles of nucleotide-modulated binding and release of client proteins. Current models for Hsp70 allostery have come from extensive study of the bacterial Hsp70, DnaK. Extending our understanding to eukaryotic Hsp70s is extremely important not only in providing a likely common mechanistic framework but also because of their central roles in cellular physiology. In this study, we examined the allosteric behaviors of the eukaryotic cytoplasmic Hsp70s, HspA1 and Hsc70, and found significant differences from that of DnaK. We found that HspA1 and Hsc70 favor a state in which the nucleotide-binding domain (NBD) and substrate-binding domain (SBD) are intimately docked significantly more as compared to DnaK. Past work established that the NBD–SBD interface and the helical lid–β-SBD interface govern the allosteric landscape of DnaK. Here, we identified sites on these interfaces that differ between eukaryotic cytoplasmic Hsp70s and DnaK. Our mutational analysis has revealed key evolutionary variations that account for the population shifts between the docked and undocked conformations. These results underline the tunability of Hsp70 functions by modulation of allosteric interfaces through evolutionary diversification and also suggest sites where the binding of small-molecule modulators could influence Hsp70 function.

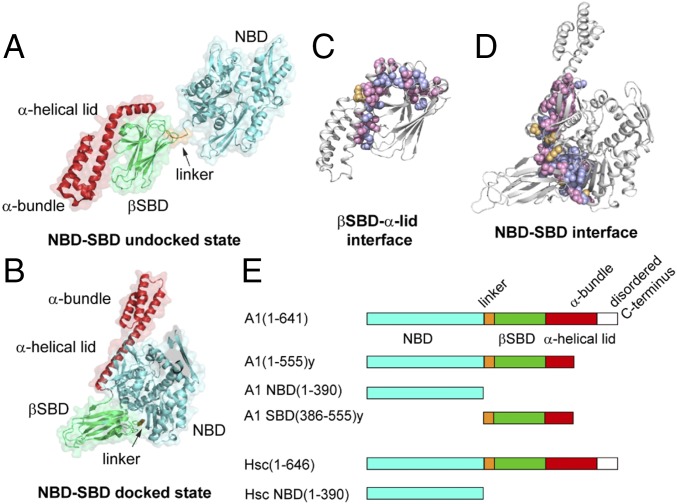

The 70-kDa heat shock proteins (Hsp70s) are ubiquitous molecular chaperones that play critical roles in a wide range of cellular processes, including protein folding/refolding, disaggregation, membrane translocation, and assembly of multiprotein complexes (1, 2). Hsp70s are composed of two domains: an N-terminal 45-kDa actinlike nucleotide-binding domain (NBD) and a C-terminal 30-kDa substrate-binding domain (SBD), which are connected by a conserved, largely hydrophobic interdomain linker. The SBD consists of a β-sandwich subdomain (β-SBD), which contains a canonical substrate-binding pocket, an α-helical lid subdomain (α-lid), and a disordered C-terminal region. Hsp70s perform their cellular functions by binding and releasing client proteins in a nucleotide-dependent fashion (3–5). For example, in the case of the Escherichia coli Hsp70 DnaK, ATP binding facilitates substrate release, and, in turn, substrate binding stimulates the ATP hydrolysis rate. In the ADP-bound state of DnaK, the NBD and SBD are undocked, the linker is relatively exposed and dynamic, and the two-domain chaperone behaves as “beads on a string” (Fig. 1A) (6, 7). The SBD adopts a closed conformation, and the two subdomains—the β-SBD and the α-lid—form a stable β-SBD–α-lid interface, resulting in low substrate on/off rates and high binding affinity. Upon ATP-binding, an allosteric signal is transmitted from the NBD to the SBD through the interdomain linker (8, 9), and the protein undergoes a major conformational change (Fig. 1B). The α-lid detaches from the β-SBD and both the α-lid and the β-SBD become docked to the NBD (10–12). As a result, the SBD adopts an open conformation with high substrate on/off rates and low affinity for substrate. Our earlier studies of DnaK showed that its bias toward different allosteric states results from an energetic tug-of-war between two orthogonal interfaces: the NBD–SBD interface and the β-SBD–α-lid interface (SI Appendix, Fig. S1) (13). The NBD–SBD interface is fully formed in the ATP-bound, docked conformation of the Hsp70, while the β-SBD–α-lid interface forms in the undocked state.

Fig. 1.

Conformational features of Hsp70 allostery. (A and B) Structures of DnaK showing the canonical ADP-bound undocked state [Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID code 2kho] (A) and the canonical ATP-bound docked state (PDB ID code 4b9q) (B). (C) Residue conservation on the undocked state β-SBD–α-lid interface. Residues are mapped on the SBD structure of HspA1 (PDB ID code 4po2). (D) Residue conservation on the docked state NBD–SBD interface among HspA1, Hsc70, and DnaK. Residues are mapped on the homology model of HspA1 based on ATP–BiP structure (PDB ID code: 5e84). (C and D) Residues in blue are conserved among HspA1, Hsc70, and DnaK; residues in pink are conserved between HspA1 and Hsc70, but different in DnaK; residues in orange are not conserved between HspA1 and Hsc70. (E) HspA1 and Hsc70 constructs used in the current study. All NBD and two-domain constructs contain a T204A mutation; A1(residues 1 to 555)y and A1 SBD(residues 386 to 555)y constructs contain an L542Y mutation.

Thirteen isoforms of human Hsp70s have been identified and are present in all major cellular compartments, including two major cytoplasmic isoforms: the stress-inducible Hsp70, HspA1, and the constitutive cognate Hsp70, Hsc70. The expression level of HspA1, which is implicated in the etiology of several cancers and neurodegenerative diseases (14–16), is low under physiological conditions but greatly augmented under stress. Hsc70, which is 86% identical in sequence to HspA1, carries out distinct cellular functions. It plays a central role in cellular homeostasis and functions in specialized cellular processes like clathrin-mediated endocytosis (17–19). Some of the differences in cellular roles of HspA1 and Hsc70 relate to their differential expression, but others may arise from differential substrate specificity and allosteric properties. Enhanced understanding of the origin of allosteric tuning in eukaryotic Hsp70s can be used to better understand other Hsp70 family members as well.

Current models for the allosteric mechanism of eukaryotic Hsp70s rely heavily on what has been learned from DnaK. However, HspA1 and Hsc70 are only 46% identical in sequence to DnaK. Importantly, sequence alignments reveal that many of the evolutionary residue changes among Hsp70s occur on the interdomain interfaces that are critical to the allosteric mechanism (Fig. 1 C and D and SI Appendix, Figs. S1–S3). Thus, we hypothesized that the differences in sequence between eukaryotic Hsp70s and DnaK modulate their allosteric landscapes, giving rise to significant functional diversification. Therefore, it is critical to assess the mechanistic impact of the evolutionary sequence diversification between DnaK and different eukaryotic Hsp70s.

Results

Design of Eukaryotic Hsp70 Constructs for Study of Allostery.

The allosteric transitions of Hsp70 molecular chaperones involve docking and undocking of the NBD and SBD as modulated by ligand binding (Fig. 1). Studies of DnaK and other Hsp70s have allowed us to dissect the allostery of Hsp70s based on different allosteric units (6, 8, 13). In the current study, we designed two-domain constructs as well as individual NBD and SBD constructs to probe the allosteric landscape of HspA1 and Hsc70 (Fig. 1E). The T204A mutation is incorporated to decrease the ATP hydrolysis rate in all NBD and two-domain constructs (20). In this work, HspA1 T204A is referred to as HspA1, and Hsc70 T204A is referred to as Hsc70. We characterized the conformational properties of HspA1 and Hsc70 in five different ligand-bound states: the apo state (no nucleotide and no peptide), the ADP-bound state, the ADP/peptide-bound state, the ATP-bound state and the ATP/peptide-bound state. Two classic Hsp70 model substrate peptides, NR (NRLLLTG) and p5 (CLLLSAPRR), are used as substrates in the current study to provide parallel comparisons with DnaK.

The Response of Eukaryotic Hsp70s to Nucleotide Binding Differs from That of DnaK.

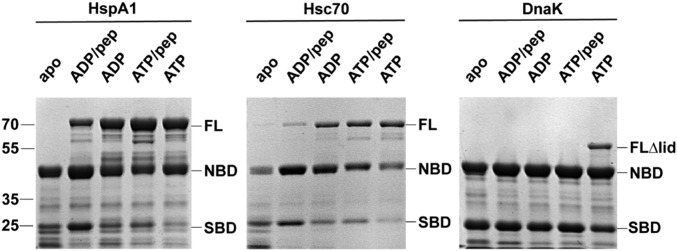

Limited proteolysis experiments are a useful approach to investigate the conformation properties of Hsp70s (21, 22). We interrogated the domain–domain docking of HspA1 in different ligand-bound states using limited proteolysis with proteinase K. As a reference, we carried out the proteolysis reaction on DnaK in the apo state or when bound to ADP or ADP plus peptide NR and when bound to ATP or ATP plus peptide (Fig. 2). Note that the band corresponding to full-length 70-kDa DnaK disappears at low proteinase K concentrations and that two bands at ∼45 and 25 kDa, corresponding to individual NBD and SBD, emerge. These observations are consistent with the fact that the NBD and SBD are undocked (in the apo, ADP-bound, and ADP/peptide-bound states) or largely undocked (ATP/peptide-bound state), which exposes the proteolytically labile interdomain linker. In ATP-bound DnaK, a band corresponding to the two-domain construct (appearing at 60 kDa due to a partial cleavage of the SBD α-lid) persists after protease treatment, arguing that the linker region is more resistant to proteolysis, in agreement with the fact that ATP-bound DnaK adopts a domain-docked conformation in which the linker is intimately packed between the NBD and SBD (10, 11).

Fig. 2.

Limited proteolysis experiment suggests a major allosteric landscape difference among HspA1, Hsc70, and DnaK. Limited proteolysis experiments on HspA1, Hsc70, and DnaK at 15 min reaction time. The full-length protein (FL), full-length protein with lid truncated (FLΔlid), NBD, and SBD bands are indicated. Peptide NR is used as a model substrate. pep, peptide.

By contrast, limited proteolysis experiments on HspA1 show that the full-length protein is protease-resistant to a substantial extent in the ADP/peptide-, ADP-, ATP/peptide-, and ATP-bound states (Fig. 2). We quantified the SDS/PAGE gels by densitometry and used portions of the two-domain bands to evaluate the resistance of HspA1 to proteinase K in different ligand-bound states (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Only in the apo state is the full-length protein seen to be rapidly digested into individual NBD and SBD fragments. All other ligand-bound states are resistant to proteolysis. Specifically, the ATP-, ATP/peptide-, and ADP-bound states have a similar degree of resistance, whereas peptide binding makes the ADP-bound state of HspA1 become increasingly labile to proteolysis. These results argue that the docked conformation of HspA1 is favored under a much wider array of ligand-binding conditions than that of DnaK. The behavior of Hsc70 falls between those of DnaK and HspA1, with ADP-, ATP/peptide-, and ATP-bound states protease resistant and the apo and ADP/peptide-bound states labile to proteolysis, suggesting that its domain docking preference is higher than DnaK, but lower than HspA1. More subtle distinctions upon limited proteolysis can be seen in the band patterns and are discussed in SI Appendix, SI Discussion.

The ATP Hydrolysis Rates of Eukaryotic Hsp70s Are Less Stimulated by Model Peptide Substrates As Compared with DnaK.

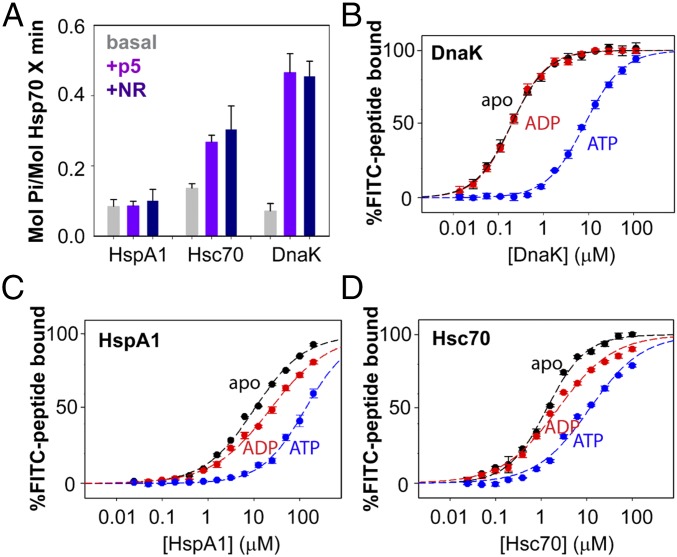

A classic hallmark of allostery in Hsp70s is the two-way communication between the SBD and NBD, as indicated by ATP modulation of substrate-binding affinity and substrate activation of the ATP hydrolysis rate. In the case of DnaK, binding of peptide substrates can stimulate the ATP hydrolysis rate significantly; the extent of stimulation is qualitatively correlated with the measured affinity of binding, consistent with an energetic coupling between ligand binding and the population of an NBD state characterized by high ATPase activity (23). We performed ATPase assay for wild-type DnaK, Hsc70, and HspA1 using both peptide p5 and peptide NR. Either model peptide stimulated the DnaK ATPase approximately sixfold (Fig. 3A). Strikingly, we found that the ATPase activity of wild-type HspA1 cannot be stimulated by either peptide NR or peptide p5, even in 500-fold molar excess, while that of wild-type Hsc70 can be stimulated to a moderate extent—approximately twofold (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

The eukaryotic Hsp70s exhibit different ATPase stimulation and substrate binding properties compared with DnaK. (A) ATPase activity of HspA1, Hsc70, and DnaK (at 2 µM) in the absence and presence of 1 mM model peptide substrate p5 or NR. Error bars represent the SDs from three independent experiments. (B–D) Binding affinities of FITC-labeled p5 to full-length HspA1, Hsc70, and DnaK in apo (black), ADP-bound (red), and ATP-bound (blue) states. Error bars represent the SDs from three independent experiments. The KD values are listed in SI Appendix, Table S1.

We measured the binding affinities of peptide p5 to HspA1 and Hsc70 and compared them with its binding to DnaK. HspA1 has significantly lower substrate-binding affinity than DnaK does in corresponding ligand-bound states, while the binding affinity of Hsc70 falls between those of HspA1 and DnaK (Fig. 3 B–D and SI Appendix, Table S1): The apparent KD of ADP-bound HspA1 to peptide p5 is 23 ± 2 µM, which is 120-fold higher than that of ADP-bound DnaK (KD = 0.19 ± 0.01 µM) and 10-fold higher than that of ADP-bound Hsc70 (KD = 2.3 ± 0.2 µM). The KD of ATP-bound DnaK/p5 is 8.2 ± 0.2 µM, whereas the KD of ATP-bound HspA1/p5 is 130 ± 10 µM. The decreased peptide-binding affinities in eukaryotic Hsp70s compared with DnaK may be due, in part, to sequence changes in the substrate-binding pocket of their SBDs. However, the preference for NBD–SBD docking and the consequent population of the low substrate-affinity state certainly account, in large measure, for the decreased peptide-binding affinity in eukaryotic Hsp70s. The lower peptide-binding affinity of HspA1 relative to Hsc70 supports this interpretation, as their substrate-binding pockets are highly conserved (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). Presumably, the reduced peptide-binding affinity contributes to the lack of ATPase stimulation by peptide substrates in these Hsp70s.

Methyl-TROSY NMR Reveals Key Features of the Eukaryotic Hsp70 Allosteric Landscapes That Are Distinct from That of DnaK.

NMR proved to be a powerful method to gain functionally important insights into the chaperone allosteric mechanism (8, 13, 24–26). 13C methyl transverse relaxation optimized spectroscopy (methyl-TROSY) NMR is particularly informative (13, 27–29), so we deployed this approach to explore the allosteric landscapes of eukaryotic Hsp70s and to compare their features to those of DnaK.

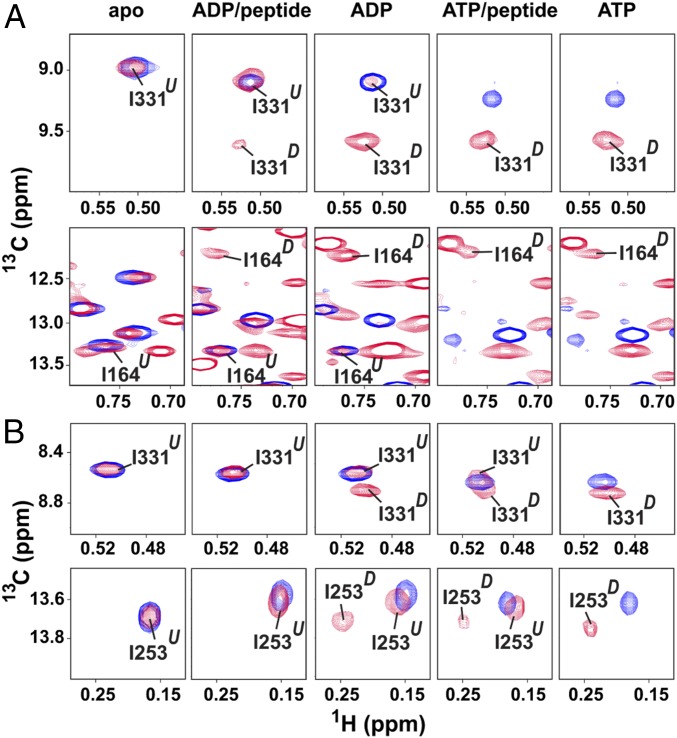

The Ile δ-methyl chemical shifts of the isolated NBD(residues 1 to 390) constructs in a given nucleotide-bound state provide a reference point for the allosteric state in which the NBD and SBD are independent of one another (i.e., undocked). We compared chemical shifts for the Ile methyl groups in the full-length eukaryotic Hsp70s in the apo state and in the ADP- or ATP-bound states, plus or minus NR peptide as model substrate, to those of the corresponding NBD (Fig. 4 and SI Appendix, Fig. S6). Note first that in the apo state, the NBD peaks from the full-length eukaryotic Hsp70s overlay exactly on those of their respective NBDs(residues 1 to 390), arguing that the NBD and SBD are predominantly noninteracting. The full-length SBD construct of HspA1 encompassing residues 386 to 641 is very prone to self-association and thus cannot be directly used in this analysis. Therefore, we compared spectra of a truncated two-domain construct, A1(residues 1 to 555)y, with isolated A1 NBD(residues 1 to 390) and A1 SBD(residues 386 to 555)y spectra, and we observed exact overlaps between peak positions for the two-domain construct and those for the isolated domain constructs (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). Together, these data argue that the apo state of eukaryotic Hsp70s adopts predominantly an undocked conformation, which is the same behavior as that of DnaK in the apo state.

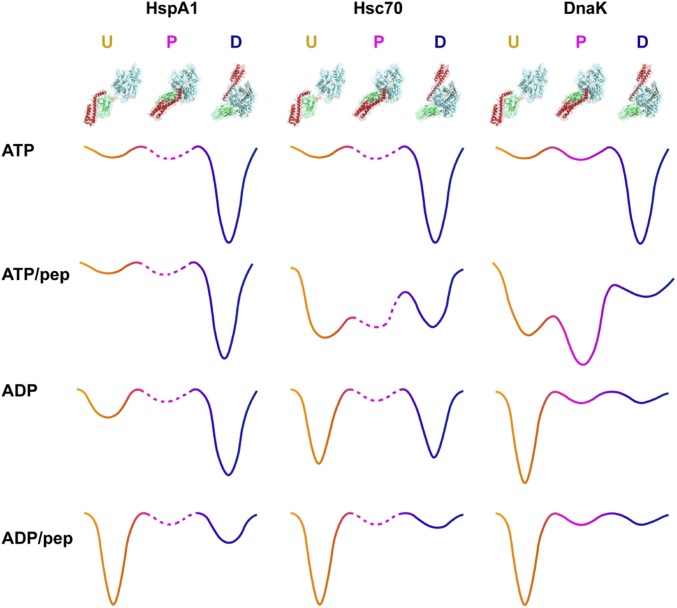

Fig. 4.

Methyl-TROSY NMR reveals characteristics of the HspA1 and Hsc70 allosteric landscapes. Blowup of diagnostic regions of the Ile methyl-TROSY spectra of apo, ADP/NR-, ADP-, ATP/NR-, and ATP-bound states of HspA1(residues 1 to 641) (A) and Hsc70 (residues 1 to 646) (B). Spectra of full-length proteins (in red) are overlaid on the spectra of the corresponding nucleotide-bound states of the individual NBD(residues 1 to 390) for each Hsp70 (in blue). The docked state resonance (D) and undocked state resonance (U) are labeled. Peptide NR is used as model substrate. The spectra of full Ile region are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S6. Additional panels with enlarged and labeled peaks are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S9 (HspA1) and SI Appendix, Fig. S10 (Hsc70).

Addition of ATP to either full-length eukaryotic Hsp70 caused significant chemical shift changes such that the observed resonances no longer overlap those of the ATP–NBD(residues 1 to 390) spectrum (Fig. 4 and SI Appendix, Figs. S6 and S7). In particular, the residues on NBD–SBD interface exhibit significant chemical shift changes (SI Appendix, Fig. S8). These observations support the conclusion that the NBD and SBD dock on one another, which is also the same behavior displayed by ATP–DnaK (10, 11). Striking differences emerge when the ADP-bound eukaryotic Hsp70s are examined. Both ADP-bound HspA1 and Hsc70 populate two distinct slowly interconverting states, indicated by the presence of two resonances for many Ile methyls: One set of peaks is coincident with the domain-undocked conformation (Fig. 4 and SI Appendix, Figs. S6, S9, and S10); and nearly all peaks in the other set (with I28 of Hsc70 the only exception, SI Appendix, Fig. S11) overlay well with peaks for the ATP-bound state and, thus, can be attributed to the domain-docked conformation. The allosteric behaviors of HspA1 and Hsc70 do differ: The ADP-bound HspA1 construct is 80% docked based on the peak volumes of well-separated peaks, whereas ADP-bound Hsc70 populates the docked state significantly less (46%). The spectral quality of the ADP-bound HspA1 and Hsc70 is similar to their ATP-bound state, but not as good as their apo state or the isolated domains. Line shape broadening is observed for the ADP-bound and ATP-bound spectra. This broadening may be caused by a combination of slower tumbling of the molecules due to domain docking and the dynamic and heterogeneous features of the docked state. Addition of NR shifted the allosteric balance of both eukaryotic Hsp70s toward the undocked allosteric state: For Hsc70, the ADP/peptide-bound chaperone is predominantly undocked, whereas a minor population (23%) of the docked form of HspA1 remains, even when ADP and peptide are bound (Fig. 4 and SI Appendix, Figs. S6, S9, and S10). These observed behaviors of HspA1 and Hsc70 are distinct from observations of DnaK and other Hsp70s that have been studied, all of which are completely undocked in the ADP-bound state (SI Appendix, Fig. S12) (13, 28, 30, 31).

In the case of DnaK, binding of peptide substrate to the ATP-bound state favors SBD helical lid closure and partial NBD–SBD undocking to form the allosterically active state (12, 13). This ATP/peptide-bound state of DnaK is largely undocked, which is also confirmed by the limited proteolysis data presented above. However, ATP/peptide-bound HspA1, based on methyl-TROSY NMR data, even in the presence of a 50-fold molar excess of peptide substrate NR, adopts a predominantly docked conformation (Fig. 4 and SI Appendix, Figs. S6 and S9). This behavior is consistent with the observation that peptide substrate cannot stimulate the ATPase of HspA1, since the activation of the ATPase by substrate requires undocking between NBD and SBD while the linker must remain bound to NBD (13). For Hsc70, adding peptide substrate to the ATP-bound state favors domain undocking (Fig. 4 and SI Appendix, Figs. S6 and S10); the population of undocked conformation is 64% (which includes fully and partially undocked species). This is consistent with the fact that peptide substrates can stimulate the ATPase rate of Hsc70 only moderately.

Evolutionary Residue Changes on Key Interdomain Interfaces Account for the Change of Allostery Between Eukaryotic Hsp70s and DnaK.

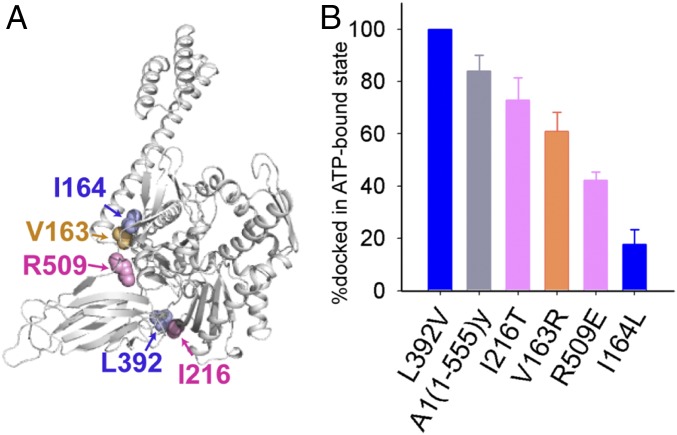

Sequence alignments demonstrate that there are numerous evolutionary residue changes among Hsp70s on the two key allosteric interdomain interfaces—that is, the NBD–SBD interface and the β-SBD–α-lid interface (Fig. 1 C and D and SI Appendix, Figs. S1–S3). We hypothesized that residue changes on the key allosteric interfaces are particularly influential to the Hsp70 allosteric mechanisms. In particular, given the preference for the domain-docked state in HspA1 relative to DnaK, we anticipated that the residue changes responsible for their distinct allosteric landscapes would either stabilize the NBD–SBD interface or destabilize the β-SBD–α-lid interface. To test this hypothesis, we made HspA1 variants with a V163R, I164L, I216T, L392V, or R509E mutation (Fig. 5 and SI Appendix, Fig. S13) on the NBD–SBD interface in the homology model of HspA1, based on the known structures of DnaK. The mutations were based on A1(residues 1 to 555)y construct, and their docking/undocking behaviors were compared with A1(residues 1 to 555)y in the ATP-bound state. These mutations were designed to perturb the docking/undocking equilibrium in a way that can be rationalized by the nature of the mutation. Mutation of conserved residues should perturb the populations of the docked and undocked states in a similar pattern for HspA1 and DnaK; for residues that are not conserved between HspA1 and DnaK, mutation of the residue in HspA1 to the one in DnaK should favor domain undocking of ATP-bound HspA1. We evaluated the populations of docked conformations by integrating the peak volumes of I253, I331, and I343 resonances of docked and undocked species for each variant in the ATP-bound state (Materials and Methods and SI Appendix, Fig. S13) and compared them to that of A1(residues 1 to 555)y.

Fig. 5.

Evolutionary residue changes on key interdomain interfaces modulate Hsp70 allostery. (A) Sites probed by mutagenesis to study the origins of allosteric differences between HspA1 and DnaK on the NBD–SBD interface; mutations are introduced in the background of the HspA1 A1(residues 1 to 555)y construct. Residues are colored as in Fig. 1 C and D. (B) Comparisons of docked populations of NBD–SBD interface mutants and A1(residues 1 to 555)y in the ATP-bound state. The populations are calculated from NMR peak volumes of I253, I331, and I343 in the undocked and docked states. The averages and SDs are calculated. The docked and undocked state resonances of I253, I331, and I343 of A1(residues 1 to 555)y and all other interface mutants are displayed in SI Appendix, Fig. S14.

R509 is in the loop connecting the β-SBD and the α-lid. Sequence alignment shows that R509 is highly conserved between eukaryotic cytosolic and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) Hsp70s (e.g., HspA1, Hsc70, and BiP) but is missing in prokaryotic Hsp70s (e.g., DnaK) and in mitochondrial Hsp70s. The ATP-bound structure of BiP shows that this Arg forms two hydrogen bonds with D178 (D152 in HspA1) in the NBD (Fig. 5 and SI Appendix, Fig. S13A) (32). As expected, the ATP-bound R509E mutant has a reduced population of the docked conformation (42% docked) relative to ATP-bound A1(residues 1 to 555)y (84% docked) and favors the undocked conformation. Mutation I164L, which perturbs the hydrophobic cluster formed between the NBD and the α-lid in the docked state of HspA1 and DnaK (Fig. 5 and SI Appendix, Fig. S13B), significantly favors domain undocking in both of these Hsp70s. Mutation of V163 in the same hydrophobic cluster to the corresponding DnaK residue (Arg) also favors domain undocking, with 61% docked population in the ATP-bound state. In DnaK, a soft mutation in the linker, L390V, has been shown to stabilize the NBD–β-SBD interface in the docked state (13). A comparable mutation in HspA1, L392V, exhibits the same effect to favor domain docking (Fig. 5 and SI Appendix, Fig. S13C). L390 (L392 in HspA1) interacts with T215 in the NBD hydrophobic cleft in the ATP-bound DnaK structure. This Thr becomes an Ile (I216) in HspA1. Thus, the increased hydrophobicity in this site is expected to contribute to the elevated domain-docking preference in HspA1. This expectation is confirmed by that fact that the I216T variant of HspA1 mutant populates the docked conformation to a lesser extent (73%) in the ATP-bound state.

The HspA1(residues 1 to 641) I164L and R509E mutants display significantly higher basal ATPase rates than that of wild type (SI Appendix, Fig. S15). This is consistent with these two mutations’ favoring domain undocking of HspA1 and increasing the population of the allosterically active (higher ATPase) state. In addition, we observed that the ATPase rates of both mutants can be stimulated modestly by peptide p5, with 1.5-fold stimulation for I164L and 1.7-fold for R509E (SI Appendix, Fig. S15). By comparison, no stimulation from peptide substrate is observed for the wild-type protein.

In the SBD of DnaK, there are three pairs of salt bridges formed between the β-SBD and the α-lid. Examining the distances between the participating atoms in these salt bridges in the HspA1 SBD demonstrates that two of them are weakened (longer) compared with those in DnaK (SI Appendix, Fig. S16A and Table S2). The weaker salt bridges in HspA1 at the β-SBD–α-lid interface are expected to favor NBD–SBD docking. We made the DnaK(residues 1 to 638) D540A,K548A mutant, which removes the salt bridges, and compared its methyl-TROSY spectrum with the spectrum of DnaK(residues 1 to 638) in the ATP/peptide-bound states (SI Appendix, Fig. S16B). Indeed, the data demonstrate that domain docking is favored in DnaK(residues 1 to 638) D540A,K548A (SI Appendix, SI Discussion). Thus, the two salt bridges stabilize the β-SBD–α-lid interface, and the decreased salt bridge strength in HspA1 compared with DnaK can favor domain docking.

Discussion

The evolutionary features of the allosteric landscapes of Hsp70s underlie their functional diversities. In this work, we investigated the allosteric landscapes of the eukaryotic cytoplasmic Hsp70s HspA1 and Hsc70 and compared them to that of the E. coli Hsp70 DnaK. From our domain dissection, biochemical assays, and methyl-TROSY NMR results, we found marked differences between the allosteric landscapes of eukaryotic Hsp70s and that of DnaK. In general, eukaryotic Hsp70s favor NBD–SBD domain docking significantly more than DnaK does (schematically illustrated in Fig. 6). Strikingly, ADP-bound HspA1 adopts a predominantly docked conformation (80%), and ADP-bound Hsc70 is 46% docked. These behaviors are distinct from other Hsp70s that have been studied, all of which are completely or largely undocked in the ADP-bound state: DnaK (6, 7), BiP (ER-resident Hsp70) (28, 30), and Ssc1 (mitochondrial Hsp70) (31). The ATP-bound state of HspA1 and Hsc70 both adopt the docked conformation, which is the same as DnaK. However, model peptide substrates have different effects on the ATP-bound state of eukaryotic Hsp70s and DnaK. In the case of DnaK, the ATP/peptide-bound state adopts a partially docked conformation (“P” state), with the NBD and SBD largely undocked and the linker bound to NBD, which is correlated to ATPase stimulation (13). In contrast, the ATP/peptide-bound HspA1 remains docked upon addition of high concentration of peptide substrate, and ATPase data show that addition of model substrate peptides does not stimulate its ATPase. Thus, we speculate the P state is not populated in the ATP/peptide-bound state of HspA1 (Fig. 6). For Hsc70, NMR data show that the model substrate peptide favors domain undocking (36% remains docked in the ATP/peptide-bound Hsc70), and peptide substrates stimulate its ATPase moderately (approximately twofold). Therefore, based on these results, we speculate that the P state is populated in the ATP/peptide-bound state of Hsc70, but to a lesser extent than in the case of DnaK (Fig. 6). While peptide substrate has a very minor effect on ATP-bound HspA1, it can shift ADP-bound HspA1 from 80% docked to 77% undocked. We attribute these different responses to peptide of ATP-bound HspA1 and ADP-bound HspA1 to be due to the effect of nucleotide. The affinity of peptide for the ADP-bound state of HspA1 is higher than the affinity for the ATP-bound state; therefore, its influence on the allosteric equilibrium is greater. Also, we conclude that ADP and ATP exert different effects on the energetics of the docked state of HspA1. Although both nucleotides favor domain docking of HspA1, the ATP-bound HspA1 docked conformation is more energetically favorable than the ADP-bound HspA1 docked conformation.

Fig. 6.

Evolutionary tuning of Hsp70 energy landscapes. Schematic illustration of allosteric landscapes of HspA1, Hsc70, and DnaK in different ligand-bound states. D represents the docked state; U represents the undocked state; and P represents the partially docked state observed in ATP/peptide-bound DnaK, with the NBD and SBD largely undocked and with the linker still bound to NBD (13). The energy landscapes are drawn based on NMR, ATPase, and limited proteolysis data; the barrier heights and well depths are only qualitative. Binding of ATP favors NBD–SBD docking of all three Hsp70s. Peptide substrate stimulates the ATPase activity of DnaK significantly and favors NBD–SBD undocking of ATP-bound DnaK to form a domain undocked/linker-bound, allosterically active P state (13). In contrast, peptide substrate addition shows only minor effects on the ATP-bound state of HspA1 and cannot stimulate its ATPase activity. Thus, we show a very shallow energy well for the P state of HspA1. Peptide substrate favors partial domain undocking of ATP-bound Hsc70 and stimulates its ATPase moderately. Therefore, we conclude that the P state is partially populated in ATP/peptide-bound Hsc70. We show the depths of the P states of the eukaryotic Hsp70s in dashed lines, because we lack direct data to distinguish undocked from partially undocked and we rely on peptide ATPase activation. ADP-bound DnaK is completely undocked, whereas ADP-bound HspA1 is predominantly docked and ADP-bound Hsc70 falls in between. The depths of the wells for undocked and docked states in our landscapes reflect this striking distinction among the Hsp70s. A fuller discussion of the rationale for depicting the energy landscapes is described in SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods.

Our previous studies demonstrated that the allosteric properties of DnaK result from an energetic tug-of-war between two interdomain interfaces: the NBD–SBD interface and the β-SBD–α-lid interface. Mutations in DnaK foreshadowed that the allosteric landscape of Hsp70s would be highly tunable by modulating these two interfaces. By mutational studies, we demonstrate that the evolutionary residue changes occurring on these key interfaces can account for the observed differences in the allosteric behavior of HspA1 and DnaK. Mutation of conserved residues causes similar shifts between the populations of the docked and undocked states for HspA1 and DnaK. In addition, it is also possible to turn DnaK into HspA1 by tuning the NBD–SBD interface and the β-SBD–α-lid interface. For example, a comparison of the SBD structures of DnaK and HspA1 suggests that two of the three pairs of salt bridges on the β-SBD–α-lid interface are weakened in HspA1 compared with DnaK (SI Appendix, SI Discussion and Fig. S15). The DnaK D540A,K548A mutant exhibits favored domain docking compared with wild type, providing a good example of turning DnaK into HspA1. The hydrophobic cluster formed between NBD and α-lid in the docked state could also be a good target; weakening this cluster would make HspA1 more DnaK-like. For example, the V163R mutant in HspA1 favors domain undocking of HspA1. The corresponding R159V mutant in DnaK should favor domain docking of DnaK (more HspA1-like). Our findings clearly show that evolutionary residue changes on interfaces key for allosteric communication in Hsp70s can tune their allosteric energy landscapes (Fig. 6). What are the functional consequences of this tuning? Distinct allosteric landscapes of eukaryotic Hsp70s can be crucial for the diversity and specificity of Hsp70 functions. While prokaryotic cells have highly streamlined protein homeostasis networks with multifunctional chaperones deployed for a range of functions, eukaryotes have evolved distinct chaperone networks to perform specialized functions (33, 34). Eukaryotic Hsp70s interact with a broad spectrum of substrates; poising them more delicately between docked and undocked states leads them to be further tunable by the affinity for a given substrate. Moreover, their tunability enables them to engage in specific cochaperone partnerships with different Hsp40s and nucleotide-exchange factors (NEFs) for particular functions; this specificity of chaperone/cochaperone teams is consistent with the much more expanded repertoires of Hsp40s and NEFs present in eukaryotes compared to prokaryotes (35). In addition to the implications of evolutionary tuning of allosteric landscapes, the deeper understanding afforded by our findings may invite novel approaches to the design of small-molecule modulators of Hsp70 functions. Targeting the regions shown to tune the allosteric behavior provides new target sites for designed inhibitors and activators. For example, our mutagenesis data demonstrates that the allostery of HspA1 is very sensitive to the NBD–α-lid interface. Two mutations on this interface, V163R and I164L, can perturb the population of docked conformation significantly. In particular, the two eukaryotic cytosolic Hsp70s, HspA1 and Hsc70, exhibit residue variation on this interface; V163 in HspA1 becomes T163 in Hsc70. Thus, it may be possible to design small molecules that recognize one of the two eukaryotic cytosolic Hsp70s on this interface and perturb its allostery while leaving the other one unaffected.

The physiological implications of the different allosteric landscapes of the prokaryotic and eukaryotic Hsp70s are not yet clear; however, studies have shown that the SBD of Hsp70s can adopt opened conformations to accommodate and bind folded structures or large substrates (30, 36, 37). The favored domain docking and the consequent SBD opening of eukaryotic Hsp70s observed in this study might be important for them to accommodate an array of large substrates, given that eukaryotic proteomes exhibit increased complexity with a higher proportion of large proteins and more complex protein folds as compared with prokaryotes (38, 39).

Materials and Methods

Construct design, protein expression and purification, NMR spectroscopy, limited proteolysis experiment, ATPase assay, substrate binding assay, sequence alignment, homology model, molecular graphics, and determining the energy landscapes of HspA1, Hsc70, and DnaK are described in detail in SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Alexandra Pozhidaeva for critical reading of the manuscript and Anne Gershenson, Charles English, and Abhay Thakur for helpful discussions. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants GM027616 and GM118161 (to L.M.G.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1811105115/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Mayer MP, Bukau B. Hsp70 chaperones: Cellular functions and molecular mechanism. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:670–684. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4464-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartl FU, Bracher A, Hayer-Hartl M. Molecular chaperones in protein folding and proteostasis. Nature. 2011;475:324–332. doi: 10.1038/nature10317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mayer MP. Hsp70 chaperone dynamics and molecular mechanism. Trends Biochem Sci. 2013;38:507–514. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zuiderweg ER, et al. Allostery in the Hsp70 chaperone proteins. Top Curr Chem. 2013;328:99–153. doi: 10.1007/128_2012_323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kityk R, Vogel M, Schlecht R, Bukau B, Mayer MP. Pathways of allosteric regulation in Hsp70 chaperones. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8308. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swain JF, et al. Hsp70 chaperone ligands control domain association via an allosteric mechanism mediated by the interdomain linker. Mol Cell. 2007;26:27–39. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bertelsen EB, Chang L, Gestwicki JE, Zuiderweg ER. Solution conformation of wild-type E. coli Hsp70 (DnaK) chaperone complexed with ADP and substrate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:8471–8476. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903503106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhuravleva A, Gierasch LM. Allosteric signal transmission in the nucleotide-binding domain of 70-kDa heat shock protein (Hsp70) molecular chaperones. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:6987–6992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014448108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.English CA, Sherman W, Meng W, Gierasch LM. The Hsp70 interdomain linker is a dynamic switch that enables allosteric communication between two structured domains. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:14765–14774. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.789313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kityk R, Kopp J, Sinning I, Mayer MP. Structure and dynamics of the ATP-bound open conformation of Hsp70 chaperones. Mol Cell. 2012;48:863–874. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qi R, et al. Allosteric opening of the polypeptide-binding site when an Hsp70 binds ATP. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:900–907. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lai AL, et al. Key features of an Hsp70 chaperone allosteric landscape revealed by ion-mobility native mass spectrometry and double electron-electron resonance. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:8773–8785. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.770404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhuravleva A, Clerico EM, Gierasch LM. An interdomain energetic tug-of-war creates the allosterically active state in Hsp70 molecular chaperones. Cell. 2012;151:1296–1307. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evans CG, Chang L, Gestwicki JE. Heat shock protein 70 (hsp70) as an emerging drug target. J Med Chem. 2010;53:4585–4602. doi: 10.1021/jm100054f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gabai VL, Yaglom JA, Waldman T, Sherman MY. Heat shock protein Hsp72 controls oncogene-induced senescence pathways in cancer cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:559–569. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01041-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park HS, et al. Heat shock protein hsp72 is a negative regulator of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:7721–7730. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.22.7721-7730.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeLuca-Flaherty C, McKay DB, Parham P, Hill BL. Uncoating protein (hsc70) binds a conformationally labile domain of clathrin light chain LCa to stimulate ATP hydrolysis. Cell. 1990;62:875–887. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90263-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bercovich B, et al. Ubiquitin-dependent degradation of certain protein substrates in vitro requires the molecular chaperone Hsc70. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:9002–9010. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.14.9002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor IR, et al. The disorderly conduct of Hsc70 and its interaction with the Alzheimer’s-related tau protein. J Biol Chem. 2018;293:10796–10809. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.002234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang J, et al. Structural basis of J cochaperone binding and regulation of Hsp70. Mol Cell. 2007;28:422–433. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kamath-Loeb AS, Lu CZ, Suh WC, Lonetto MA, Gross CA. Analysis of three DnaK mutant proteins suggests that progression through the ATPase cycle requires conformational changes. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:30051–30059. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.50.30051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Preissler S, et al. AMPylation targets the rate-limiting step of BiP’s ATPase cycle for its functional inactivation. eLife. 2017;6:e29428. doi: 10.7554/eLife.29428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mayer MP, et al. Multistep mechanism of substrate binding determines chaperone activity of Hsp70. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:586–593. doi: 10.1038/76819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karagöz GE, et al. N-terminal domain of human Hsp90 triggers binding to the cochaperone p23. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:580–585. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011867108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saio T, Kawagoe S, Ishimori K, Kalodimos CG. Oligomerization of a molecular chaperone modulates its activity. eLife. 2018;7:e35731. doi: 10.7554/eLife.35731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sekhar A, Rosenzweig R, Bouvignies G, Kay LE. Hsp70 biases the folding pathways of client proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E2794–E2801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1601846113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sekhar A, Rosenzweig R, Bouvignies G, Kay LE. Mapping the conformation of a client protein through the Hsp70 functional cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:10395–10400. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1508504112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wieteska L, Shahidi S, Zhuravleva A. Allosteric fine-tuning of the conformational equilibrium poises the chaperone BiP for post-translational regulation. eLife. 2017;6:e29430. doi: 10.7554/eLife.29430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenzweig R, Sekhar A, Nagesh J, Kay LE. Promiscuous binding by Hsp70 results in conformational heterogeneity and fuzzy chaperone-substrate ensembles. eLife. 2017;6:e28030. doi: 10.7554/eLife.28030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marcinowski M, et al. Substrate discrimination of the chaperone BiP by autonomous and cochaperone-regulated conformational transitions. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:150–158. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mapa K, et al. The conformational dynamics of the mitochondrial Hsp70 chaperone. Mol Cell. 2010;38:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang J, Nune M, Zong Y, Zhou L, Liu Q. Close and allosteric opening of the polypeptide-binding site in a human Hsp70 chaperone BiP. Structure. 2015;23:2191–2203. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2015.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Albanèse V, Yam AY, Baughman J, Parnot C, Frydman J. Systems analyses reveal two chaperone networks with distinct functions in eukaryotic cells. Cell. 2006;124:75–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nillegoda NB, Bukau B. Metazoan Hsp70-based protein disaggregases: Emergence and mechanisms. Front Mol Biosci. 2015;2:57. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2015.00057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kampinga HH, Craig EA. The HSP70 chaperone machinery: J proteins as drivers of functional specificity. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:579–592. doi: 10.1038/nrm2941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schlecht R, Erbse AH, Bukau B, Mayer MP. Mechanics of Hsp70 chaperones enables differential interaction with client proteins. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:345–351. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mashaghi A, et al. Alternative modes of client binding enable functional plasticity of Hsp70. Nature. 2016;539:448–451. doi: 10.1038/nature20137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Balchin D, Hayer-Hartl M, Hartl FU. In vivo aspects of protein folding and quality control. Science. 2016;353:aac4354. doi: 10.1126/science.aac4354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koonin EV, Wolf YI, Karev GP. The structure of the protein universe and genome evolution. Nature. 2002;420:218–223. doi: 10.1038/nature01256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.