Abstract

Background

Oral anticoagulants reduce the risk of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF), but are underused. AURAS-AF (AUtomated Risk Assessment for Stroke in AF) is a software tool designed to identify eligible patients and promote discussions within consultations about initiating anticoagulants.

Aim

To investigate the implementation of the software in UK general practice.

Design and setting

Process evaluation involving 23 practices randomly allocated to use AURAS-AF during a cluster randomised trial.

Method

An initial invitation to discuss anticoagulation was followed by screen reminders appearing during consultations until a decision had been made. The reminders required responses, giving reasons for cases where an anticoagulant was not initiated. Qualitative interviews with clinicians and patients explored acceptability and usability.

Results

In a sample of 476 patients eligible for the invitation letter, only 159 (33.4%) were considered suitable for invitation by their GPs. Reasons given were frequently based on frailty, and risk of falls or haemorrhage. Of those invited, 35 (22%) started an anticoagulant (7.4% of those originally identified). A total of 1695 main-screen reminders occurred in 940 patients. In 883 instances, the decision was taken not to initiate and a range of reasons offered. Interviews with 15 patients and seven clinicians indicated that the intervention was acceptable, though the issue of disruptive screen reminders was raised.

Conclusion

Automated risk assessment for stroke in atrial fibrillation and prompting during consultations are feasible and generally acceptable, but did not overcome concerns about frailty and risk of haemorrhage as barriers to anticoagulant uptake.

Keywords: anticoagulants, atrial fibrillation, electronic health records, reminder systems, stroke

INTRODUCTION

Patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) are at five times increased risk of thromboembolic stroke.1 Oral anticoagulants (OAC) reduce stroke risk by 64% in AF.2 Despite this, underuse has been reported globally.3,4 The barriers to OAC uptake are multiple, and include patient, clinician, and healthcare system factors.5 The authors attempted to address this problem by developing a reminder intervention (AURAS-AF, AUtomated Risk Assessment for Stroke in AF), promoting discussions about anticoagulants within primary care consultations.

Absolute contraindications to OAC account for only a minority of the reasons patients are not offered them. In the Adderley et al study,6 these were defined as a clinically coded diagnosis within the previous 2 years of: haemorrhagic stroke, major bleeding (gastrointestinal, intracranial, intraocular, retroperitoneal), bleeding disorders (haemophilia, other haemorrhagic disorders, thrombocytopaenia), peptic ulcer, oesophageal varices, aneurysm, or proliferative retinopathy; a record of allergy or adverse reaction to anticoagulants; a record of pregnancy in the previous 9 months; or severe hypertension with a mean (of the three most recent measures in the previous 3 years) systolic blood pressure of >200 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure of >120 mmHg. These criteria applied to just 6% of patients with atrial fibrillation in that study.6

Reminder interventions improve clinician behaviour, but the effect size is generally small to modest.7 Systems that provide advice for patients and practitioners concurrently, or require clinicians to supply a reason for overriding advice, are more likely to succeed.8 The authors developed AURAS-AF with these characteristics in mind.

The stroke risk of a patient with AF can be estimated using validated scoring systems based on information in the electronic health record.9 AURAS-AF was trialled in 46 practices located over a wide region of England. It provided automated stroke risk assessment of patients with AF.10 This generated a letter of invitation to discuss oral anticoagulants sent to all eligible patients, provided their GPs agreed that this was appropriate. Whether or not the invitation was sent, screen reminders appeared during subsequent consultations during a 6-month intervention period until a decision had been made.

How this fits in

Oral anticoagulants are known to reduce substantially the elevated stroke risk of people with atrial fibrillation, but uptake is suboptimal. Concern over frailty and risk of falls and haemorrhage were frequently given as reasons to avoid this treatment. Only a minority of patients at high risk of stroke have absolute contraindications, but two-thirds of patients in this study were considered unsuitable to invite to discuss the issue with their GP. This represents a significant gap between recommended and real-world practice.

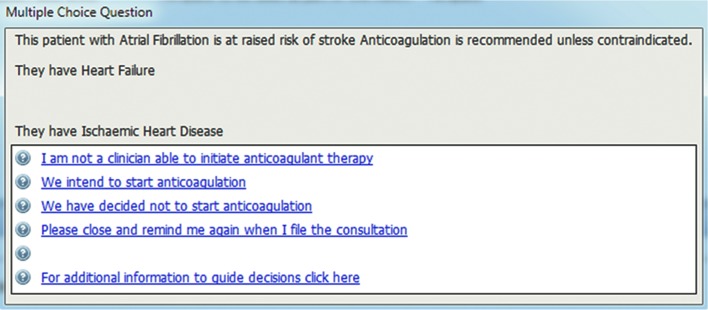

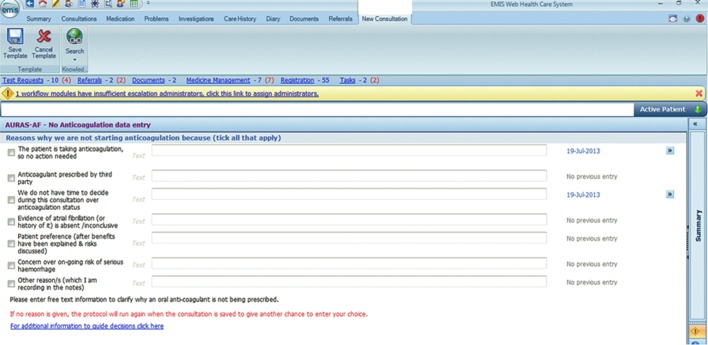

The main reminder messages were activated by a doctor or nurse opening the electronic record, and queried whether a decision had been taken to start an anticoagulant. A number of response options were presented (Figure 1). When the second option was selected (given as ‘We intend to start anticoagulation’), reminders would continue to appear in future consultations until the patient was using an anticoagulant. When the third option was selected (given as ‘We have decided not to start anticoagulation’), a further template opened, requiring a reason for not initiating (Figure 2). This further template’s first two options would be used when the software had not detected prescriptions for OAC — for example, if they were issued by a hospital clinic.

Figure 1.

Main reminder message with options.

Figure 2.

Template requiring a reason for not initiating an oral anticoagulant.

A further template in the third option was designed to avoid rushing a decision during what would typically be a consultation about some other issue. The fourth option might be used where the patient’s original AF diagnosis was, on further inspection, poorly substantiated. Such patients could have the code ‘AF resolved’ applied, removing them from the AF register. This is a different group from those with paroxysmal AF, who remain on the register and should be risk assessed in the same way as those with persistent AF. Those with ‘AF resolved’ have recently been shown to have a significantly raised stroke risk compared with controls without an AF history,11 but they are not likely to be considered for OAC unless AF recurs. All options apart from the third would result in the reminders no longer appearing in future consultations.

The software was installed remotely, and was active for 6 months (February to August 2014). The authors found a non-significant difference in prescribing of OAC after 6 months, and a reduction (of borderline significance) in incidence of stroke and haemorrhage at 12 months in the intervention practices versus controls.12

The process evaluation outlined in the current study aimed to identify the barriers to automated stroke risk assessment linked to invitations and screen reminders in primary care.

METHOD

The process evaluation involved the 23 intervention practices (that is, those using the AURAS-AF tool). It included both quantitative and qualitative components, as recommended.13

The authors recorded the numbers of patients invited to discuss anticoagulants, the reasons given when GPs decided they were unsuitable, and the outcome of discussions. These were recorded by practices using proforma. The data generated when users responded to the main reminder to select an option were extracted remotely. An experienced qualitative researcher conducted semi-structured interviews with clinicians (by telephone) and patients (face to face or by telephone). Topic guides captured researcher-led issues around AURAS-AF, and allowed people to express their own experiences and priorities (further information is available from the authors on request). They lasted around 30 minutes, were audiorecorded, transcribed verbatim, and analysed thematically through a framework approach, using NVivo 10 software.

Framework analysis is a systematic process of sifting, charting, and sorting material according to key issues and themes,14 and is particularly useful for applied research around focused questions. Following familiarisation with the data, the transcripts were coded for anticipated and emergent themes. A chart summarising key perspectives and themes was developed to provide an overview of the full dataset. All intervention practices were invited to participate in qualitative interviews.

RESULTS

The 46 trial practices provided a combined patient population of 359 937, with 6429 patients with AF at baseline (20 February 2014), of which 5339 (83%) were eligible for OAC. Of these, 3340 (62.6%) had already been treated, leaving 1999 untreated. The AURAS-AF tool was used in half (23) of these practices (therefore affecting approximately 1000 individuals). These practices represented all quintiles of the English Index of Multiple Deprivation (2015) based on the practice postcode.

Inviting patients to discuss oral anticoagulants

Proforma data were returned from 11 practices describing the process of invitations to discuss OAC. In these practices, out of a total of 476 patients identified as eligible to be invited at baseline, only 159 (33.4%) were considered by GPs to be appropriate to invite (Table 1). This outcome varied considerably between practices, with median 35.7% and range 10 to 100%. In all, 35 were commenced on OAC, giving a mean of 22% conversion to OAC among those invited. This also varied between practices, with median 18.2% and range 0% to 66.7%. The overall proportion of the patients originally deemed eligible to invite that were converted was 7.4% (practice median 4.5%, with range of 0% to 23.3%).

Table 1.

Proportions of patients invited for discussion, and discussion outcomes

| Practice | Eligible for invitation, n | Number invited, n | Proportion invited, % | Number starting, n | Proportion of those invited starting, % | Proportion of those eligible starting, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 40 | 4 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 70 | 7 | 10 | 1 | 14.3 | 1.4 |

| 3 | 22 | 4 | 18 | 1 | 25 | 4.5 |

| 4 | 69 | 7 | 10.1 | 2 | 28.6 | 2.9 |

| 5 | 60 | 21 | 35 | 14 | 66.7 | 23.3 |

| 6 | 23 | 14 | 60.9 | 3 | 21.4 | 13 |

| 7 | 48 | 21 | 43.8 | 2 | 9.5 | 4.2 |

| 8 | 56 | 20 | 35.7 | 3 | 15 | 5.4 |

| 9 | 37 | 18 | 48.6 | 1 | 5.6 | 2.7 |

| 10 | 41 | 33 | 80.5 | 6 | 18.2 | 14.6 |

| 11 | 10 | 10 | 100 | 2 | 20 | 20 |

| All practices: | 476 | 159 | 33.4 | 35 | 22 | 7.4 |

| Median | 35.7 | 2 | 18.2 | 4.5 |

For the 317 patients considered unsuitable, the commonest reasons (mentioned ≥10 times) for not inviting are grouped and summarised in Table 2. The most frequently occurring were frailty, haemorrhage risk, and risk of falls. A number were allotted more than one of these reasons, and 120 (38%) were given at least one of the three. In some cases, it appeared the GP recording the reasons was unaware that patients who are no longer fibrillating should be risk assessed in the same way as a patient who is fibrillating permanently.

Table 2.

Reasons given for not inviting patients to discuss anticoagulation

| Reason | Number of mentions (more than one may apply to an individual) |

|---|---|

| Frailty | 56 |

| Haemorrhage risk | 49 |

| Risk of falls | 38 |

| Patient preference/refusal | 38 |

| Not in atrial fibrillation | 35 |

| Cancer or terminal illness/end of life | 27 |

| Already discussed OAC | 24 |

| Dementia | 16 |

| Anaemia | 15 |

| Already taking anticoagulant | 12 |

OAC = oral anticoagulant.

Other reasons were given less frequently, and included concerns about compliance, past adverse reactions to OAC, the separate need for an antiplatelet drug for coronary artery disease, and specific risks such as liver failure, severe heart failure, alcoholism, and uncontrolled blood pressure.

Responses to screen prompts

The authors extracted the coded data indicating the responses to the screen prompts remotely from practices. A total of 1695 main reminders occurred in 940 patients (mean 1.8 times per patient). Table 3 gives the number of responses of the GPs to the prompt options. In 883 instances, the decision was taken not to initiate and a range of reasons offered (Table 3).

Table 3.

Responses to the main screen messages (data represent the total number of events across 22 intervention practices)a

| Responses to the screen reminder | Number of events, n (%) |

|---|---|

| I am not a clinician qualified to initiate anticoagulant therapy | 479 |

|

| |

| We intend to start OAC | 333 |

|

| |

| We decided not to start OAC | 883 |

| Patient already taking OAC/prescribed by third party | 28 (3.2) |

| Insufficient time in this consultation | 159 (18.0) |

| Evidence of AF absent or inconclusive | 55 (6.2) |

| Patient preference to avoid OAC | 130 (14.7) |

| Concern over haemorrhage risk | 187 (21.2) |

| Other reasons | 324 (36.7) |

One intervention practice withdrew data-sharing consent prior to the process evaluation searches, leaving 22 practices contributing data to this part of the evaluation. This withdrawal did not affect the other outcome analyses. AF =atrial fibrillation. OAC =oral anticoagulant.

GP interviews

There were 7 GPs interviewed.

The advantages of automated reminders

Most GPs felt that the combination of opportunistic and systematic identification of patients worked well, and that the software had the potential to trigger further discussion about anticoagulation with patients who had declined it in the past:

‘I think it’s very useful to remind us … because sometimes patients change their attitudes, and this does help to remind you of that, you must have that discussion again with some patients.’

(GP06, partner in a deprived town practice)

A recently qualified GP felt that it might offer a useful approach for other more established partners:

‘For some of the other partners, I have to say, who are reluctant themselves to put elderly patients on anticoagulants for perceived risks … it’s been helpful for them as well.’

(GP06)

Though some GPs used prior knowledge of their patient’s medical history and preferences to enable them to think about the best approach, a more recently qualified GP felt that being new to the practice and not knowing the patients very well might have had benefits:

‘I’m not coming from a position of having had conversations with them from way back, and then trying to change my stance. I am just trying to revisit their past medical history and get to know them.’

(GP06)

Tailored decision making

The GPs the authors interviewed saw distinct advantages in using the software, but emphasised that treatment decisions should be tailored to the individual:

‘With an increasing elderly population with lots of other comorbidities, I think you have to make very balanced decisions about risk of stroke, versus risk of falling, versus risk of bleeding.’

(GP01, senior partner, 17 years’ experience)

‘I think good care has to be tailored to the individual patient. You can’t have a blanket rule.’

(GP06)

Most tailored the information they gave to individual patients, taking into account their health literacy. Where the practice population were ‘switched on and well educated’ (GP02, registrar), this might include providing details about risk factors, and stroke risk scores and statistics, whereas more simplistic explanations might be considered more appropriate for patients who were less able to engage with specific clinical information.

GP03 (GP associate, large town practice with rural patients) recognised that patients sometimes make decisions GPs may not agree with and that, although the study had been designed to address the underuse of anticoagulants, framing the objectives in this way implied that doctors were not doing their job properly:

‘I can make recommendations and they can ask me my opinion … but people take time to come to their own decisions.’

(GP03)

This GP felt that the conversation might need to be revisited several times before some patients would consider taking an anticoagulant. Nonetheless, having a reminder system to ensure that the matter remains on the agenda could be beneficial to ensure that it does not get forgotten.

Using reminders

Managing the reminder system in the context of the consultation setting was also discussed in interviews. This brought up the problem of multiple opportunistic ‘pop-ups’ in current practice, competing for the usual 10 minutes available:

‘We might have six or seven of them [reminders], and once you’ve got … worked through about three or four, and then there’s this anticoagulation … you think, well that’s another 5 or 10 minutes of consultation … so you leave it.’

(GP05, 10 years’ experience, runs warfarin-monitoring programme in a rural practice)

But GPs also described how they had used the reminders to introduce discussion about OAC into a consultation. Typically, after asking the patient about the problem they had consulted about, the GP would then indicate that they too had something to discuss:

‘So they know something else is coming, and once they’ve finished speaking about their problem and you’ve sorted it, you can say: “There’s a few things on your medical notes that are popping up to alert us, one of them is about the risk of developing stroke.” And then you would lead on to this conversation.’

(GP05)

The opportunity depended to some extent on the time that was available, and prioritising the patient’s own agenda:

‘It really depended on the patient’s agenda, you don’t want to make them feel they haven’t actually had the outcome they wanted from the consultation before you dive in and actually talk about what you want to talk about.’

(GP07, 3 years qualified, predominantly affluent area, pockets of deprivation, large number of older patients)

In some cases, GPs recognised that the timing was not right to initiate a discussion:

‘If they come and they’re actually sick, you can’t then talk to them about a preventative medication because, you know, they’re too unwell to start it anyway. Whilst they’re sick they can’t make any treatment decisions, they’re just in pain or unwell.’

(GP05)

Limitations of the intervention

Some GPs pointed out how AURAS-AF was dependent on robustly coded data. This could be further complicated by the transfer of records from secondary to primary care, and when patients transferred from other practices:

‘With some of the primary care databases … it’s only as good as the coding is. Historically, our coding sometimes hasn’t been great, which is something we’ve been working on in the last 2 years.’

(GP04, partner in a town practice, lead for research)

One GP would have liked an option in the reminder box to reflect the fact that records are often accessed for other purposes than a consultation:

‘If I’m writing consultation notes that aren’t face-to-face meetings … trying to put administration notes regarding medication, for example, you’re not actually speaking to the patient at the time, and there was no option to put “this is not a consultation, I can’t discuss it at this time”. It was difficult to put anything in other than “we’ve deferred this decision”.’

(GP07)

Pressing the ‘I am not a clinician able to initiate anticoagulation therapy’ option in order to overcome this problem was used as a way round this by one GP. This tendency may explain the higher than expected number (479) of these screen responses. None of the GPs the authors interviewed was aware of reminders impacting negatively on non-clinical staff, as the AURAS-AF tool was only active when a clinician was logged on.

Patient interviews

Patients had either been invited by letter to discuss anticoagulant medication with their GP, or had discussed it opportunistically during a routine appointment, as part of the trial. Interview participants ranged in age from 66 to 90 (mean 80) years, nine male and six female. Eight took place in the patient’s home, and seven were conducted by telephone.

It was difficult for the patients to say much about the trial software, as they were largely unaware of it. The key issue that arose in relation to the intervention was around receipt of the study invitation letter. Some found it difficult to recall the correspondence they had received about the trial. Additionally, many had comorbidities and found it difficult to separate AF from other health problems, or to recall the history of their conversations about anticoagulants.

Of those who recalled receiving the letter, some remembered feeling surprised, as they had not felt they were candidates for anticoagulants. For example, one patient had paroxysmal atrial fibrillation and rarely experienced any symptoms:

‘It only happens once in a blue moon, so I mean … my wife has it all the time. It’s fibrillating all the time but, mine is, I’ve got a completely solid pulse rate as long as I take the atenolol, and I’ve had no trouble since.’

(Pat08)

He nevertheless felt reassured to know that his GP was keeping a check on things, and felt positive about the invitation to review his medication:

‘I was surprised to get it but, nevertheless, I thought, well, that’s good. They’re checking up on me.’

(Pat08)

Another patient felt that the invitation letter was inappropriate in his case as he had recently been given a terminal cancer diagnosis, and had previously decided in discussion with his GP to stop taking medications:

‘You see, my cancer has taken over and I’ve already … so that’s just a round robin.’

(Pat14)

One patient (Pat02) had not fully understood the letter, and had assumed it was about something ‘more serious’:

Patient (P): ‘I went to see the GP because he sent me the letter.’

Interviewer (I): ‘And how did you feel about getting the letter and being asked to go and see him?’

P: ‘I thought it was something, [er] I don’t if it’s correct to say, something more serious.’

I: ‘What did it make you feel, when you got the letter?’

P: ‘Have I got cancer?’ (Pat02)

Other patient narratives concerned their responses to being originally diagnosed with AF, the conversations they had had with the GP in the past about anticoagulants prior to the study, their perceptions about anticoagulants, and their medical care in general.

DISCUSSION

Summary

AURAS-AF was found to be an appropriate and acceptable tool, but did not overcome the major barriers to OAC uptake. Current guidance9 considers frailty and risk of falls to be usually insufficient reasons to withhold anticoagulants, but reluctance to prescribe for such patients was highly prevalent among the GPs in the study. Risk of haemorrhage should be assessed when considering OAC, but the purpose of this is to identify and modify factors raising this risk, not, in most cases, to allow it to override OAC initiation. Only one-third of those eligible for an invitation to discuss OAC were considered suitable to be invited. Among those not invited, a number went on to have thromboembolic events during the study, and were then initiated on an anticoagulant in hospital. These outcomes were evident in the audit of cardiovascular events in the main trial report.12 Despite being flagged up through AURAS-AF, these individuals had to experience an event before their need, and suitability, for OAC was recognised.

Comparison with existing literature

A positive impact of a decision support system on OAC uptake was recently reported in a study from Sweden, with a similarly small (but in this case significant) effect size.15 In keeping with other literature,16–18 the authors of the current study found through their mixed methods a substantial concern over frailty and risk of haemorrhage and falls on the part of the clinicians caring for these patients. A recent study suggesting that older AF patients with chronic kidney disease may have adverse thromboembolic outcomes but reduced mortality following OAC did not separate transient ischaemic attacks (TIA) from thromboembolic strokes.19 A similar paradoxical finding resulted simply from detection bias for TIA in the authors’ main trial.12

There is evidence that doctors overestimate the risks of OAC,20 and that informed patients may accept treatment at a lower threshold of expected benefit than that at which clinicians would recommend them.21 Patients in this study may have been discussing this treatment with a GP unconvinced about the net overall benefit in frailer patients.22 The authors found wide variation between practices in their willingness to invite people for conversations about OAC. Their findings concur with those of Induruwa et al, who demonstrated a similar tendency for clinical frailty to influence decisions on OAC,23 despite its non-inclusion in the currently established risk factors relevant to risk–benefit discussions.9

Strengths and limitations

The study included practices across a wide range of sociodemographic and geographical locations. The authors demonstrated the potential of web-based electronic record systems to support pragmatic trials requiring remote collection of anonymised outcome data. They were limited by incomplete capture of proforma for the invitation process, which were only returned by 11 out the 23 intervention practices. However, all 23 took part in the other aspects of the evaluation. Recruitment for the qualitative interviews was also less than expected. Resources limited the intervention duration to 6 months, and this may not have been long enough to produce an impact of the software on OAC prescribing rates.

Implications for research and practice

Under guidelines developed since the study was conceived, the majority of patients with AF are now considered eligible for OAC, so the specific challenge of identifying them has become less of a problem. However, making the treatment thresholds clearer does not overcome the tendency for clinicians to take decisions on behalf of patients, and this study has emphasised the ongoing need to overcome this tendency.

The authors’ interview data suggested a range of attitudes towards OAC therapy within the same practice. It is important that newly diagnosed patients have early access to a clinician who is well informed about the benefits and risks of OAC therapy. This clinician might be a GP, an arrhythmia nurse specialist, or a pharmacist. The ability of the software to revisit the anticoagulant issue in those who have previously declined treatment supports current guidance that the decision should be reviewed regularly.24

This study adds to an increasing evidence base that automated reminder systems that may be effective at changing practice require detailed consideration of the numerous factors likely to determine impact on clinician behaviour.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the funding body, the NIHR Clinical Research Network (Primary Care), the participating practices, EMIS Health, and the Data Monitoring and Trial Steering Committees.

Funding

The study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) (SPCR/FR6/173). FD Richard Hobbs is supported by the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was granted by NRES Committee South Central, Berkshire. Reference: 13/SC/0026.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.Wolf PA, Abbott RD, Kannel WB. Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke — the Framingham study. Stroke. 1991;22(8):983–988. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.8.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hart RG, Pearce LA, Aguilar MI. Meta-analysis: antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients who have non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(12):857–867. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-12-200706190-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogilvie IM, Newton N, Welner SA, et al. Underuse of oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation: a systematic review. Am J Med. 2010;123(7):638–645.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holt TA, Hunter TD, Gunnarsson C, et al. Risk of stroke and oral anticoagulant use in atrial fibrillation: a cross-sectional survey. Br J Gen Pract. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Bungard TJ, Ghali WA, Teo KK, et al. Why do patients with atrial fibrillation not receive warfarin? Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(1):41–46. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adderley N, Ryan R, Marshall T. The role of contraindications in prescribing anticoagulants to patients with atrial fibrillation: a cross-sectional analysis of primary care data in the UK. Br J Gen Pract. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Shojania KG, Jennings A, Mayhew A, et al. The effects of on-screen, point of care computer reminders on processes and outcomes of care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(3):CD001096. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001096.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roshanov PS, Fernandes N, Wilczynski JM, et al. Features of effective computerised clinical decision support systems: meta-regression of 162 randomised trials. BMJ. 2013;346:f657. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D, et al. 2016 ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(38):2893–2962. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holt TA, Fitzmaurice DA, Marshall T, et al. AUtomated Risk Assessment for Stroke in Atrial Fibrillation (AURAS-AF) — an automated software system to promote anticoagulation and reduce stroke risk: study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14:385. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-14-385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adderley NJ, Nirantharakumar K, Marshall T. Risk of stroke and transient ischaemic attack in patients with a diagnosis of resolved atrial fibrillation: retrospective cohort studies. BMJ. 2018;361:k1717. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holt TA, Fitzmaurice DA, Marshall T, et al. Automated software system to promote anticoagulation and reduce stroke risk: cluster randomised controlled trial. Stroke. 2017;48:787–790. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.015468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2015;350:1258. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: Bryman A, Burgess RG, editors. Analysing qualitative data. London: Routledge; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karlsson LO, Nilsson S, Bång M, et al. A clinical decision support tool for improving adherence to guidelines on anticoagulant therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation at risk of stroke: a cluster-randomized trial in a Swedish primary care setting (the CDS-AF study) PLoS Med. 2018;15(3):e1002528. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sellers MB, Newby LK. Atrial fibrillation, anticoagulation, fall risk, and outcomes in elderly patients. Am Heart J. 2011;161(2):241–246. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dharmarajan TS, Varma S, Akkaladevi S, et al. To anticoagulate or not to anticoagulate? A common dilemma for the provider: physicians’ opinion poll based on a case study of an older long-term care facility resident with dementia and atrial fibrillation. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2006;7(1):23–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donzé J, Clair C, Hug B, et al. Risk of falls and major bleeds in patients on oral anticoagulation therapy. Am J Med. 2012;125(8):773–778. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar S, de Lusignan S, McGovern A, et al. Ischaemic stroke, haemorrhage, and mortality in older patients with chronic kidney disease newly started on anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation: a population based study from UK primary care. BMJ. 2018;360:k342. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Man-Son-Hing M, Laupacis A. Anticoagulant-related bleeding in older persons with atrial fibrillation: physicians’ fears often unfounded. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(13):1580–1586. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.13.1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Man-Son-Hing M, Laupacis A, O’Connor A, et al. Warfarin for atrial fibrillation. The patient’s perspective. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(16):1841–1848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olesen JB, Lip GYH, Lindhardsen J, et al. Risks of thromboembolism and bleeding with thromboprophylaxis in patients with atrial fibrillation: a net clinical benefit analysis using a ‘real world’ nationwide cohort study. Thromb Haemost. 2011;106(4):739–749. doi: 10.1160/TH11-05-0364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Induruwa I, Evans NR, Aziz A, et al. Clinical frailty is independently associated with non-prescription of anticoagulants in older patients with atrial fibrillation. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2017;17:2178–2183. doi: 10.1111/ggi.13058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Atrial fibrillation: management CG180. London: NICE; 2014. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg180 (accessed 10 Oct 2018) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]