Highlights

-

•

National Cancer Control Programmes (NCCPs) are key elements in cancer control.

-

•

NCCPs’ role in national cancer policies of EU countries has grown significantly.

-

•

Few quantitative assessments are available to evaluate success or failure of the implementation of NCCPs.

-

•

Research on methodologies to better assess the effectiveness of cancer prevention policies should be enhanced.

Keywords: Cancer prevention, National Cancer Control Programmes, Policy, Best practice, European Union

Abstract

Through the application of science to public health practice, National Cancer Control Programmes provide the framework for the development of policies on cancer control, with the ultimate goal of reducing cancer morbidity and mortality, and improving quality of life. In the last decade, a substantial number of Member States in the European Union (EU) have formulated and/or updated their National Cancer Control Programmes, Plans or Strategies including primary prevention (health promotion and environmental protection), secondary prevention (screening and early detection), integrated care and organization of services, and palliative care as main elements. Although tobacco control and population-based screening policies are examples of best practices that are gradually being implemented in most of the EU countries, there are still large regional differences in cancer burden arising from the wide variety of social determinants and other epidemiological factors, along with gaps in the policy and practical articulation of cancer control within the health systems. On the other hand, few quantitative assessments are available with regard to evaluating the success or failure of the implementation of these programmes, especially in terms of reducing cancer incidence or mortality. An EU framework to better assess of the effectiveness of cancer prevention policies and the factors triggering shortfall in best practices implementation seems imperative.

1. Background

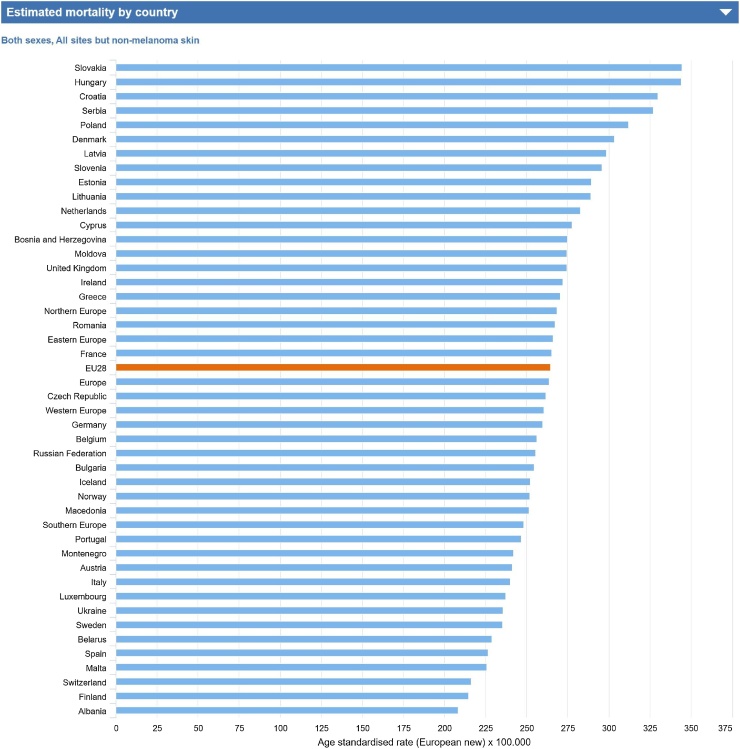

In its commitment to implement the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, the European Union (EU) has made significant progress towards the achievement of the third Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) ‘good health and well-being’. The risk of dying from premature death (under 65 years of age) due to chronic diseases has steadily decreased between 2002 and 2014; in 2014, however, cancer remained as the leading cause of premature mortality with 79 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants under 65 [1,2]. In the EU about 3 million new cancer cases were estimated in 2018 (all types, excluding non-melanoma skin cancer; 1.7 million cases in men and 1.5 million in women) with over 1.4 million cancer deaths (800,000 in men and 600,000 in women), accounting for 26% of all deaths and posing a major public health problem [3]. The most common cancers and causes of cancer death among men in the EU are prostate, lung and colorectal cancers, whereas breast, colorectal and lung are the leading cancer sites among women. Within Europe there remain large regional differences in cancer burden (Fig. 1) [3] that may reflect a wide variety of social and epidemiological factors including differences in implementation of cancer prevention and screening programmes by governments, exposure to different risk factors, lifestyle habits and access to health services.

Fig. 1.

Estimated age-standardised cancer mortality rate (age adjusted per 100,000) in Europe, by country, both sexes, all sites but non-melanoma skin, all ages, 2018.

Source: ECIS – European Cancer Information System From https://ecis.jrc.ec.europa.eu, accessed on 08/02/2018 (C) European Union, 2018.

Studies have shown that around 40% of cancer cases in the EU can be prevented through practices and actions targeted towards risk prevention at the individual and population levels [4,5]. The European Code against Cancer (ECAC) is an integrated instrument for cancer prevention that informs the general public how to avoid or reduce exposures to established causes of cancers, to adopt behaviours to reduce cancer risk, and to participate in vaccination and screening programmes under the appropriate national guidelines [6]. The ECAC stands out among other initiatives for its clarity and accessibility as a short set of recommendations for the general public. It also acts as a guide to aid development of national health policies in cancer prevention and provides an important basis for health promotion. Additionally, one of the major practical interventions to avoid premature deaths due to cancer is to ensure access to screening and early detection services linked with access to adequate treatment.

2. Cancer prevention policies in the EU

The range of available cancer prevention strategies and policies include cancer plans, population-based cancer registries and screening programmes for breast, cervical and colorectal cancer. There exists wide international heterogeneity in the extent to which these cancer control structures had been implemented in Europe. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the establishment of a National Cancer Control Programme (NCCP) offers the most rational means of achieving a substantial degree of cancer control, even where resources are severely limited, by identifying and implementing priorities for action and research. A NCCP is a public health programme that, by implementing systematic, equitable and evidence-based strategies for prevention, early detection, diagnosis, treatment and palliation, will reduce the number of cancer cases and deaths and improve quality of life of cancer patients [7]. Most NCCPs, Plans or Strategies include as main elements primary prevention (health promotion and environmental protection), secondary prevention (screening and early detection), integrated care and organization of services, and palliative care. Research, training and quality control elements are also frequently mentioned. Prevention offers the most cost-effective long-term strategy for the control of cancer, therefore, cancer policies should be implemented to raise awareness, to reduce exposure to cancer risk factors, to ensure that people are provided with the information and support they need to adopt healthy lifestyles, and to reduce cancer mortality through screening and early detection. For the purpose of this publication, we will focus on primary and secondary prevention, two areas which were potentially affected by the financial crisis in Europe, and where we made the case that the resources not used on cancer prevention efforts could lead to increased costs (both financial and human) in the longer term [8,9]; we will use the acronym NCCPs to refer to all programs, plans or strategies described.

NCCPs are key elements in cancer control and their role in national cancer policies of EU countries has grown significantly; however, there is no internationally agreed format for a NCCP nor any commonly accepted framework for analysis of their impact. Atun, Ogawa and Martín-Moreno conducted the first systematic analysis of NCCPs in Member States of the EU and other European countries and assessed the comprehensiveness of these plans and their congruence to needs [10]. This analysis (published in 2009) was based on 19 publicly available NCCPs; 12 of the countries studied had yet to formulate NCCPs. Most of the plans had significant gaps, e.g. in relation to governance, macro-organization of the health system for cancer care, financing and resource allocation for NCCPs as well as targets and timelines for achieving them. With this scenario in mind, in 2009, under the European Partnership for Action Against Cancer (EPAAC), the European Commission called upon the Member States to set up National Cancer Plans or Strategies by the end of 2013. Under the EPAAC and the Cancer Control (CanCon) Joint Actions, two surveys have been performed with the purpose of informing EU policymakers about the extent to which this goal has been achieved [11,12].

The most recent and comprehensive NCCPs listed in Table 1 have been obtained from the International Cancer Control Partnership (ICCP), the EPAAC and the WHO Non-communicable Disease Document Repository [[13], [14], [15]]. The definitions of programme, plan and strategy varies among countries; particularly plan and programme are often used interchangeably. For all the 28 EU countries, at least one of the most recent documents was identified except for Bulgaria, Croatia and the Slovak Republic (Table 1): eight countries have NCCPs; 11 countries have Cancer Control Plans; six countries have Cancer Control Strategies (Cyprus has a Strategy as well as an Action Plan); additionally, in the United Kingdom (UK), Northern Ireland has a NCCP, Scotland and Wales have a Cancer Control Plan, and England has a Cancer Control Strategy. Romania has announced in 2016 the launch of an Integrated Multi-Annual National Cancer Control Plan for 2016–2020, the document, however, has not been found by the authors [11,16]. It is interesting to note that some nations (Denmark, England, France and Malta) are acting on the basis of a third or fourth NCCP; while others (Belgium, Czech Republic, Finland, Germany, Ireland, Lithuania, Northern Ireland, Poland, Romania, Scotland, Spain and Wales) are acting on their second one. Denmark and England introduced their initial Cancer Plan as early as 2000, and Scotland in 2001, Romania in 2002, Belgium, France and Lithuania in 2003, and Poland in 2005.

Table 1.

List of NCCPs identified.

| Country | Most recent NCCPs | year of publication | Main goals, objectives, actions or recommendations on prevention described in the NCCPs (list not exhaustive) | Previous NCCPsc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | Cancer Framework Program Austria | 2014 |

|

No |

| Belgium | National Cancer Plan 2008-2010 | 2008 |

|

Cancer Strategy 2003 |

| Bulgaria | No NCCPsb | NA | NA | NA |

| Croatia | No NCCPsb | NA | NA | NA |

| Cyprus | National Cancer Control Strategy and Action Plan | 2009 |

|

No |

| Czech Republic | National Oncology Program | 2013 |

|

National Cancer Strategy 2008 |

| Denmark | National Cancer Plan IV | 2016 | (The 2016 National Cancer Plan supplements earlier cancer plans from 2000, 2005 and 2010) National objective on prevention for children, young and special groups:

|

National Cancer Plan I 2000 National Cancer Plan II 2005 National Cancer Plan III 2010 |

| Estonia | National Cancer Strategy 2007-2015 | 2007 |

|

No |

| Finland | Development of cancer prevention, early detection and rehabilitative support 2014 – 2025 | 2014 |

|

National Cancer Plan 2010 |

| France | Cancer plan 2014-2019 | 2014 | Goal 1: Promote earlier diagnoses Goal 10: Launch the National Tobacco Reduction Program Goal 11: Give everyone the means to reduce their risk of cancer (including alcohol, diet, physical activity, vaccination) Goal 12: Prevent work-related or environmental cancers (including atmospheric pollutants, ionizing radiation for diagnostic purposes, artificial and natural ultraviolet radiation, and exposure to substances classified as possible carcinogens, especially in pregnant women and young children) |

Cancer: a nation-wide mobilization plan 2003 Cancer Plan 2009-2013 |

| Germany | National Cancer Plan | 2012 |

|

National Cancer Plan 2008 |

| Greece | National cancer plan 2011-2015 | 2010 |

|

No |

| Hungary | Hungarian National Cancer Control Programme | 2006 |

|

No |

| Ireland | National Cancer Strategy 2017-2026 | NR |

|

A Strategy for Cancer Control and National Cancer Plan 2006 |

| Italy | National Oncology Plan renamed “Technical policy document on the reduction of cancer disease burden – for the years 2011-2013" | 2011 |

|

No |

| Latvia | Oncologic diseases control program for years 2009-2015 | 2009 |

|

No |

| Lithuania | National Cancer Prevention and Control Program 2014-2025 | 2014 |

|

National Cancer Prevention and Control Program 2003-2010 |

| Luxembourg | Plan National Cancer Luxembourg 2014-2018 | 2014 |

|

No |

| Malta | National Cancer Plan 2017 – 2021 | 2017 |

|

A National Cancer Plan for the Maltese Islands 2007 National Cancer Plan 2011-2015 |

| Netherlands | National Cancer Control Program 2005-2010 | 2004 |

|

No |

| Poland | Cancer Control Strategy for Poland 2015-2024 | 2014 | Objective 9: Raising the level of public health knowledge about cancer risk factors Objective 10: Promoting healthy eating habits and physical activity Objective 11: Prevention of tobacco-induced cancers Objective 12: Prevention of infection-induced cancers Objective 13: Reducing exposure to carcinogenic factors in the workplace Objective 14: Prevention of cancers caused by UV exposure Objective 15: Improving the organisation, efficacy and economic effectiveness of population based screening tests |

Establishing the Multi-Year National Cancer Control Programme 2005 |

| Portugal | National Program for oncological diseases - 2015 | 2007 |

|

No |

| Romania | Integrated Multi-Annual National Cancer Control Plan for 2016-2020a | 2016 |

|

National Cancer Plan and Strategy 2002 |

| Slovak Republic | No NCCPsb | NA | NA | NA |

| Slovenia | National Cancer Control Programme 2017-2021 | 2017 |

Obj 1: To reduce the proportion of smokers in the 15 to 64 age group from 24% to 19%, and to reduce the sale of tobacco products (cigarettes and fine-cut tobacco) by 30% Nutrition and exercise: Obj 1: To increase the proportion of six-month-old breast-fed children to 20% and to increase the proportion of 12-month-old breast-fed children, who are also given suitable supplementary food, to 40%. Obj 2: To increase the proportion of the population eating vegetables at least once a day by 10%, and to reduce the difference between the sexes. Obj 3: To increase the proportion of the population eating fruit at least once a day by 5%, and to reduce the difference between the sexes. Obj 4: To increase the proportion of the physically active population by 10%. Obj 5: To reduce the proportion of overfed and obese children and young people by 10% and to reduce the proportion of overfed and obese adults by 5%. Obj 6: To reduce the proportion of the population that frequently drinks sweet beverages, eat sweets and desserts by 15%. Obj 7: To reduce salt intake in the population by 15%. Obj 8: To reduce trans-fat and saturated fat content in foodstuffs. Obj 9: To reduce the proportion of malnourished and functionally less capable elderly people and patients. Alcohol: Obj 1: To reduce the proportion of excessive alcohol drinkers from 10.2% to 8%. Obj 2: To reduce the proportion of 15-year-olds who have already drunk alcohol at 13 or younger from 40% to 35%. Exposure to the sun and tanning beds Obj 1: To reduce the exposure to the sun and tanning beds of all generations, younger ones in particular. The working environment Obj 1: To consistently implement legislation on the safety and health at work by stressing improved risk assessments, especially in workplaces and in living environments that are exposed to carcinogens. Radon: Obj 1: To use structural measures at an interministerial level in order to restrict the exposure to radon in public and private buildings in the country by 2020. Infections linked to cancer: Obj 1: To ensure at least a 75% rate of immunisation of girls (11 and 12 years old) against HPV by the end of 2021. Obj 2: To maintain a high rate of immunisation against hepatitis B (approx. 90%). Enhancing preventive approaches in primary health care: Obj 1: To include 70% of the population in prevention programmes by 2021.

Obj 2: To amend and adopt an act on databases by the end of 2018. |

National Cancer Control Programme 2010-2015 |

| Spain | Strategy in Cancer of the National Health System | 2010 |

|

Strategy in Cancer of the National Health System 2006 |

| Sweden | National Cancer Strategy | 2009 |

|

No |

| United Kingdom (England) | Achieving world-class Cancer Outcomes: a Strategy for England 2015-2020 | NR | Recommendation 2: to publish a new tobacco control plan within the next 12 months Recommendation 3: to develop and deliver a national action plan to address obesity, including a focus on sugar reduction, food marketing, fiscal measures and local weight management services Recommendation 4: to form the basis for the development of a national strategy to address alcohol consumption Recommendation 5: to determine the level at which HPV vaccination for boys would be cost-effective Recommendation 7: to develop updated guidelines for the use of drugs for the prevention of breast and colorectal cancers Recommendation 10: to roll out FIT replacing gFOBt as soon as possible Recommendation 11: to drive rapid roll-out of primary HPV testing into the cervical screening programme Recommendation 13: to examine the evidence for lung and ovarian cancer screening |

NHS Cancer Plan 2000 Cancer Reform Strategy 2007 Improving Outcomes, A Strategy for Cancer 2011 |

| United Kingdom (Scotland) | Better Cancer Care, An Action Plan 2015-2020 | 2008 |

|

Cancer in Scotland: Action for change 2001 |

| United Kingdom (Wales) | Together For Health – Cancer Delivery Plan | 2012 |

|

Design to Tackle Cancer in Wales 2006 |

| United Kingdom (Northern Ireland) | Regional Cancer Framework A Cancer Control Programme for Northern Ireland | NR |

|

Regional Cancer Framework: A Cancer Control Programme for Northern Ireland |

NA: not applicable; NR: not reported

Document not found by the authors.

Confirmed with the corresponding national institution or expert.

As mentioned earlier, the ECAC offers an exceptional public health tool to support governments to inform policy formulation, in the implementation of their cancer control strategies and policies, as well as feeds into public awareness campaigns on cancer prevention. Malta and Slovenia have recently launched their respective comprehensive National Cancer Plans for 2017–2021 which, following the structure proposed by the ECAC, stresses preventive actions to reduce the increasing number of cancer burden in the country. In order to achieve this objective, Malta’s plans focus on continuing the conduction and promotion of vaccination programmes; strengthening enforcement and monitoring of relevant legislation and regulations, including tobacco and alcohol control legislation, environment control and protection legislation, Occupational Health and Safety legislation and protection from ultraviolet radiation (UV) exposure. Additionally, the Plan will support the implementation of measures included in the Food and Nutrition Policy and Action Plan and the Healthy Weight for Life Strategy and will disseminate the ECAC in schools, workplaces, health and community centres. As regards secondary prevention, the Plan will continue updating national policies for screening for breast, colorectal and cervical cancers [17]. Likewise, Slovenia has very specific objectives for each of the recommendations of the ECAC (See Table 1) [18]. Spain highlights that the ECAC includes the best-documented recommendations concerning primary prevention and must continue being a reference point for all cancer strategies. Other countries also mention the ECAC in their NCCPs, such as: Poland, specifically under Objectives 9 on raising public knowledge of cancer risk factors, especially among children and educators, and 10 to promote healthy eating habits and physical activity; or Cyprus, Hungary and Ireland.

2.1. Primary prevention

Somewhere between a third and a half of cancer cases could be prevented through the adoption of healthier lifestyles. To this end, a number of preventive strategies are aimed at continuing to reduce tobacco consumption and passive exposure to tobacco smoke, control alcohol consumption, decrease sedentary lifestyles and further promote the adoption of healthy eating and body weights. Cancer risks posed by infectious agents (Hepatitis B virus (HBV) and Human Papilloma Virus (HPV)) and exposures to carcinogens in the environment and at work need also to be addressed [6]. Most countries explicitly describe detailed goals, objectives, actions or recommendations on primary prevention action in their NCCP (Table 1). Exceptionally, Germany focuses principally on secondary prevention, as a variety of activities to tackle common risk factors for non-communicable diseases exist outside the cancer plan. Denmark, in its most recent National Cancer Plan, focuses on prevention for children, young and special groups, as the most recent NCCP supplements earlier cancer plans from 2000, 2005 and 2010. Due to the recent nature of programme implementation and the long lead time necessary to produce evidence of its success or failure in terms of incidence or mortality, there are few quantitative results available with regard to these indicators presented in the NCCPs. Some countries, such as Denmark and England, did point to past successes either as a result of past NCCPs or of past efforts in the field of cancer control [12].

2.1.1. Tobacco and alcohol control

All NCCPs include tobacco control among their objectives, actions or recommendations; 19 of the 28 NCCPs, more than those reported in 2009 [10], specify measures on control of alcohol consumption (Cyprus, Denmark, England, Estonia, Finland, France, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Northern Ireland, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain, Scotland and Wales). In Denmark, the evaluation report of the first National Cancer Action Plan launched in 2000 has assessed the main areas of recommendations for the period 2000–2003 [19]. As recommended in the Plan, a number of initiatives have been implemented at county and national levels, e.g. legislation on tobacco control has been introduced and resources have been allocated. As a result of the smoking ban legislation and non-smoking campaigns in subsequent Cancer Plans, smoking prevalence has dropped from 23 to 20% from December 2008 to December 2010. Other areas, such as prevention of alcohol abuse and excessive drinking, still required an enhanced action. The evaluation reports of the last strategy for England show rapid progress in the first and second years of the implementation of its five year programme: e.g. since the publication of the Tobacco Control Plan a reduction of 300,000 smokers over the past three years has been documented, the lowest smoking rate since the peak reported in 1970 [20,21]. In contrast, France reports a lack of decline in the common risk factors for cancers targeted by previous Cancer Plans. According to the last report of the 2009–2013 Cancer Plan, most measures planned to reduce the attractiveness of tobacco (e.g. graphic warnings, ban on the sale of flavoured cigarettes) have been implemented, also assistance to stop smoking has been reinforced. However, tobacco sales stagnated from 2004 to 2011 with a slight decline in 2012 and 2013. Most importantly, the prevalence of smokers increased from 2005 to 2010, rising from 31.8% to 33.6%, especially among older women and the unemployed. The prevalence of smoking has stabilized at 34.1% in 2014 with a slight decrease in regular smoking among women [22].

2.1.2. Diet, obesity and physical activity

Similarly, the number of NCCPs that included healthy diet and/or obesity control as a key area has increased up to 18 countries (Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, England, France, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain, Scotland and Wales). Additionally, Ireland refers to separate supplementary plans (e.g. the National Obesity Policy & Action Plan and the National Physical Activity Plan). In Denmark, as a consequence of the implementation of the National Cancer Action Plan, actions in the areas of nutrition and physical activity have gradually increased [19]. In England, the Childhood Obesity Plan has been published in 2016 and a programme to remove excess calories from the foods that children consume the most is being developed [20,21].

2.1.3. Environmental and occupational protection

Protective measures against environmental, specifically UV radiation, and occupational exposures have been also included in almost all NCCPs (19 of the 28).

2.1.4. Vaccination

Although not addressed in all NCCPs, most National Immunization programmes include administration of HBV and HPV vaccines. All countries except Denmark and Finland have explicitly recommended HBV vaccine for all infants in diverse schedules; Denmark offers HBV vaccination to babies born to a mother infected and at high risk groups only, and Finland provides the vaccine for specific risk-groups only (to be given at the earliest age). In addition, Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, France, Germany, Greece, Latvia and Luxembourg have catch-up programs for HBV vaccination. Likewise, all EU countries have introduced HPV vaccination in their National Immunization schedule (either as mandatory or recommended), except for Bulgaria and Romania that recommend the vaccine for specific groups only. Only two countries, Austria and Croatia, recommend the vaccines for females and males, whereas Austria, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece and Luxembourg have catch-up programs at later ages [23].

2.2. Secondary prevention: implementation of cancer screening programmes in the EU

Secondary prevention is addressed in all the NCCPs, although the level of implementation differs among countries. There is established evidence that implementation of organized screening through a population-based programme can significantly reduce mortality from breast, cervical and colorectal cancers, as well as incidence of cervical and colorectal cancers [24]. It has been estimated that a total of a quarter of a million men and women died of these three cancers in 2012 in the EU. Implementation of population-based organized screening programmes with defined target populations, screening interval, protocol of testing and follow-up with comprehensive quality assurance at all levels will reduce the burden of these three cancers in the EU [25]. Achieving high coverage through improved access to high quality screening services and ensuring appropriate treatment and follow-up of the screen detected cases are key to the success of the cancer screening programmes. In 2003, the EU urged Member States to introduce or scale-up breast, cervical and colorectal cancer screening through systematic population-based approaches with quality assurance at all levels [26]. An International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) report concluded that the number of individuals having access to population-based screening in the year 2007 was much lower than the desired level and substantial opportunistic screening was ongoing in the EU [27]. Since then, some countries have demonstrated significant reductions in cancer-related mortality through well-organized population-based screening programmes. This is reported in a new 2017 IARC report updating the status of implementation and level of organization of population-based screening in the EU, including selected performance indicators in various European guidelines for quality assurance in cancer screening [25]. Table 2 shows the status of the population-based programmes for breast, cervical and colorectal cancer screening in the EU, whether the screening policy documented is enacted through law or as a result of an official recommendation, and the invitation coverage for each cancer type in the recommended age group.

Table 2.

Status of implementation of cancer screening in the European Union around 2016.

| Country | Breast cancer screening |

Cervical cancer screening |

Colorectal cancer screening |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Status of population-based programme (year of programme initiation) | Screening policy documented as law or official recommendation | Invitation coverage in 50-69 years age group (annual population)b | Status of population-based programme (year of programme initiation) | Screening policy documented as law or official recommendation | Invitation coverage in 30-59 years age group (annual population)c | Status of population-based programme (year of programme initiation) | Screening policy documented as law or official recommendation | Invitation coverage in 50-74 years age group (annual population)d | |

| Austria | Rollout complete; (2014) | OR | 0% | Non population-based | NA | NA | Rollout complete; R (2003) | OR | NR |

| Belgium | Rollout complete (2001) | Law | 99.7% | Rollout ongoing; R (2013) | OR | 33.8% | Rollout complete; R (2009) | OR | 81.4% |

| Bulgaria | Non population-based or no program | NA | NA | No program | NA | NA | No program | NA | NA |

| Croatia | Rollout complete (2006) | No policy | 104.8% | Rollout ongoing; N (2012) | OR | NR | Rollout complete; N (2008) | OR | 100.5% |

| Cyprus | Rollout complete (2003) | OR | 39.6% | No program | NA | NA | Piloting; N(2013) | OR | NR |

| Czech Republic | Rollout complete (2002) | OR | 0% | Rollout ongoing; N (2008) | OR | NR | Rollout complete; N (2000) | OR | NR |

| Denmark | Rollout complete (2008) | Law | 82.3% | Rollout complete; N (2006) | OR | 67.1% | Rollout complete; N (2014) | Law | NR |

| Estonia | Rollout complete (2003) | OR | 69.2% | Rollout complete; N (2006) | OR | 77.1% | Piloting; N(2016) | OR | NR |

| Finland | Rolloutcomplete (1987) | OR | 91.6% | Rolloutcomplete; N (1963) | OR | 97.9% | Piloting; N(2004) | OR | 10.5% |

| France | Rollout complete (2004) | OR | 102.7% | Rollout ongoing; R (1991) | OR | 7.3% | Rollout complete; Na (2002) | OR | 99.1% |

| Germany | Rollout complete (2005) | Law | 90.8% | Planning; N(2016) | Law | NR | Planning; N(2016) | Law | NR |

| Greece | Non population-based or no program | NA | NA | Non population-based | NA | NA | Non population-based | NA | NA |

| Hungary | Rollout complete (2001) | Law | 78.5% | Rollout ongoing; N (2003) | Law | 15.2% | Piloting; N(2007) | Law | 1.5% |

| Ireland | Rollout complete (2000) | OR | 110.5% | Rollout ongoing; N (2008) | OR | NR | Rollout ongoing; N (2012) | OR | 10.9% |

| Italy | Rollout complete (1990) | Law | 70.6% | Rollout ongoing; N (1989) | Law | 65.1% | Rollout ongoing; N (1982) | OR | 52.4% |

| Latvia | Rollout complete (2009) | Law | 98.4% | Rollout complete; N (2009) | OR | 92.7% | Non population-based | NA | NA |

| Lithuania | Rolloutongoing (2005) | Law | 0% | Rollout ongoing; N (2004) | Law | 75.5% | Rollout ongoing; N(2009) | Law | NR |

| Luxembourg | Rollout complete (1992) | OR | 107.5% | Non population-based | NA | NA | Planning; N (2016) | OR | NR |

| Malta | Rollout complete (2009) | OR | 78.8% | Piloting; N (2015) | OR | NR | Rollout ongoing; N (2013) | OR | 28.5% |

| Netherlands | Rollout complete (1989) | Law | 96.7% | Rollout complete; N (1970) | Law | 96.7% | Rollout ongoing; N (2014) | Law | 20.3% |

| Poland | Rollout complete (2006) | Law | 101.8% | Rollout complete; N (2006) | Law | 97.7%e | Rollout ongoing; N (2012) | Law | 12.5% |

| Portugal | Rolloutongoing (1990) | OR | 55.4% | Rollout ongoing; R (1990) | OR | 18.6%e | Rollout ongoing; R(2009) | OR | 1.6% |

| Romania | Piloting (2015) | OR | 0.2% | Rollout ongoing; N (2012) | OR | 65% | No program | NA | NA |

| Slovak Republic | Non population-based or no program | NA | NA | Planning; N (2008) | OR | NR | No program | NA | NA |

| Slovenia | Rolloutongoing(2008) | Law | 20.9% | Rollout complete; N (2003) | OR | NR | Rollout complete; N (2009) | Law | 80.0% |

| Spain | Rollout complete (1990) | Law | 84.7% | Non population-based | NA | NA | Rollout ongoing; N (2000) | Law | 11.3% |

| Sweden | Rollout complete (1986) | OR | 93.3% | Rollout complete; N (1967) | OR | 79.9% | Rollout complete; R (2008) | OR | 8.5% |

| United Kingdom | Rollout complete (1988) | OR | 111.0% | Rollout complete; N (1988) | OR | 102.1% | Rollout complete; N (2006) | OR | 58.7% |

N: nationwide; R: regional; NA: not applicable; OR: official recommendation.

Data submitted from two different sources, Calvados and rest of the country.

ndex year for invitation coverage was 2013 for all except Austria (2014), Estonia (2014), Finland (2012), France (2012), Germany (2012) and Lithuania (2014).

Index year for invitation coverage was 2013 for all except Belgium, Estonia (2014), Latvia, and Lithuania where the index year was 2014.

Index year for invitation coverage was 2013 for all except Belgium (2014), Finland (2014), France (2012), Malta (2014), Netherlands (2014), Portugal (2014) and Slovenia (2011-12).

Invitation coverage reported for all ages.

Source: adapted from Basu P et al. [25] (Note: Invitation coverage was calculated as the proportion of subjects in the target age range who were invited for screening in the index year, over the annual population. The annual population is defined as the target population divided by the screening interval, assuming that the invitations are issued uniformly during the screening interval. Given that this assumption is not always true, it should be noted that the measurement of the invitation coverage over a single year might be inaccurate. This is reflected by the reported invitation coverage exceeding 100% in some of the Member States)

Reviewing some aspects of best practices in secondary prevention, and as described by Basu et al., a large number of EU countries have implemented or are in the process of implementing population-based screening programmes in compliance with the EU recommendations. Population-based breast cancer screening (implemented or planned) among age-eligible women has increased to 95% compared to 92% in 2007. The corresponding figures for cervical cancer screening were 72% and 51% in 2016 and 2007, respectively. Colorectal cancer screening has shown the most significant improvement, with roll-out ongoing or completed in 17 countries in 2016 compared to five in 2007; access almost doubled from 58 million to 110 million people. Nevertheless, the heterogeneity in the approaches used by countries to organize quality assured services in the context of the population-based cancer screening programmes has been reflected in the wide variations in the invitation coverage. Denmark and England are the only countries with complete rollout programs at national level and high invitation coverages for the three types of cancer; followed by Sweden, with rollout completed at national level and high coverage for breast and cervical cancer screening, and rollout completed at regional level of colorectal cancer. Finland, Latvia, the Netherlands and Poland have rollout completed at national level and high coverage for breast and cervical cancer screening; and Croatia and France have rollout completed at national level and high coverage for breast and colorectal cancer screening [25].

2.3. Impact of national cancer policies

Unfortunately, there has been little research comparing the effect of national preventive policies on cancer incidence and mortality. The evidence linking specific public policies to epidemiological trends is sparse and often limited to ecological or qualitative studies, or focused on very specific interventions, such as tobacco control or screening [28]. The authors have not found quantitative studies on the direct impact of NCCPs on national cancer burden besides couple of examples. A recent study in England showed little evidence of a direct impact of the effectiveness of the NHS Cancer Plan from 2000 and related national cancer policy initiatives on one year cancer survival [29]. In France, the 2003–2007 Cancer Plan included a combination of behavioural changes alongside environmental risk factors to be taken into account (e.g. tobacco, food, alcohol, solar risk); additional objectives (e.g. fight against sedentary lifestyle, prevention of viral infections) were added in the 2009–2013 Cancer Plan. However, the evaluation report covering 2004 to 2014 reported that none of these objectives can be considered achieved [22].

In 2013, Mackenbach et al. attempted for the first time to compare quantitatively the performance of 43 European countries in 11 areas of health policy, including some cancer policies. They found substantial differences between European countries in implementation and intermediate and final health outcome. For example, in the area of tobacco control, countries like the UK, Ireland, Norway and Iceland obtained high scores, whereas Hungary, the Czech Republic, Luxembourg and Austria had low scores. As male lung cancer mortality rates are high in some counties in Central and Eastern Europe, and relatively low in most Nordic countries and in the UK and Ireland, these results may reflect the accumulated effects of policies over many years. As regards alcohol control, Luxembourg, Germany and Austria perform below the European average. Concerning diet, they showed that wealthier countries had higher levels of fruit and vegetable consumption, but also a higher proportion of fat in their diets. More importantly, this study reported important gaps in information about the implementation of health policies and their intermediate and final health impact, as a consequence of the existing comparative analyses of health policies been mostly based on policymakers’ reports [30]. Additionally, the authors also assessed whether the declines in mortality from 1970 to 2009 due to a particular cause could be explained, at least partly, by the implementation of effective health policies. In this study, Sweden stood out as having adopted the ‘best practice’ overall; the authors estimated that, if all countries had achieved the age-specific mortality rates of Sweden 150,000 fewer deaths from lung cancer and almost 120,000 fewer from cirrhosis, among others, could have been achieved by 2009 [31].

Regarding cancer screening, they found that when European countries were stratified into three groups on the basis of their national income and geographical location (North, South and East), the differences in mortality from cervical and breast cancer in those countries without a population-based screening programme were shown to be generally higher. Northern European countries with population-based cervical cancer screening had 0.8 per 100,000 cervical cancer deaths less than countries without screening in the same region; likewise, Southern Europe countries with population-based cervical cancer screening had 3.8 per 100,000 deaths less than countries without screening in the same region; and Eastern Europe countries with population-based cervical cancer screening had 1.2 per 100,000 deaths less than countries without screening in the same region. Similarly, for breast cancer, Northern European countries with population-based cancer screening had 2.4 per 100,000 deaths less than those without in the same region; 2.5 per 100,000 deaths less in Southern Europe countries with population-based breast cancer screening versus countries without in the same region; and 4.0 per 100,000 deaths less for countries in Eastern Europe with population-based breast cancer screening versus countries without in the same region. In general, as demonstrated in neighbouring countries that have pursued different health policies, the authors found that the differences in health policy performance were due to a combination of lack in financial resources and lack of political will to take such action [31].

3. Conclusions

In the EU, there has been a strong momentum towards formulating NCCPs. This trend, while promising, has not always developed the full potential of primary and secondary prevention. Prevention offers the greatest public health potential and the most cost-effective long-term cancer control strategy; the ECAC provides a solid backbone, based on evidence, for supporting NCCPs by giving two clear messages: (i) certain cancers can be avoided (and health in general can be improved) by adopting healthier lifestyles; and (ii) certain cancers can be cured, or the prospects of cure greatly increased, if they are detected at an early stage. The ECAC carries the authority and reliability of expert scientists working under the coordination of IARC; however, wider dissemination among both, citizens and policy-makers, and periodic update is needed in order to achieve full impact.

While national programmes are heterogeneous, with mechanisms subject to diverse contextual factors including resource availability, health systems capacity, organization of services, geography, epidemiology and past experience in cancer policy, all Member States are facing similar challenges in terms of the cancer burden and the need to formulate sustainable, effective and responsive policies for patients and citizens. Just as there is an objective heterogeneity in cancer incidence, prevalence and mortality across the EU, there are differences in the approach to primary and secondary prevention programmes. Additionally, implementation of these activities needs to be monitored constantly. Effective and efficient NCCP implementation needs competent management to identify priorities and resources (planning), and to organize and coordinate those resources to guarantee sustained progress to meet the planned objectives (implementation, monitoring and evaluation). Concentrating efforts in a demonstration area that will allow successful implementation of the priority areas; step by step implementation; optimizing existing resources; organizing activities with a systemic approach; education and training; and monitoring and evaluation, are some key processes to be considered when implementing a NCCP [7]. The lack of an accepted framework to aid in the formulation of a NCCP, along with the scare availability of evidence on which policies are effective and which are not, hamper the analyses of the degree of implementation of these policies and, subsequently, the population health impact of these policies. Furthermore, although long standing and operational cancer plans can be considered to be a positive asset in reducing cancer incidence and mortality, there is no simple relationship between adoption or implementation of a plan and beneficial public health outcomes. Despite the fact that, for example, Denmark, the UK, France or the Netherlands are among the earliest countries to adopt comprehensive plans, these countries also have incidence and mortality above the EU average. There are many explanations for this including the induction period or time-lag between effective implementation and behavioural change and resulting impact on outcome measures. Moreover, socio-economically disadvantaged sections of the population may be especially “hard to reach” and less susceptible to public health interventions, and this deserves to be considered in the required impact assessment research [32].

In the EU there are still important differences in health, specifically in cancer incidence and mortality, which partly reflect deficits in the implementation of best practices that are well known and unevenly established in the different Member States. Future research should help establish methodologies to better assess the effectiveness of cancer prevention policies on cancer epidemiology. Cancer prevention and control advocates must be assertive in insisting that financial constraints should not be an excuse for inaction, but rather an opportunity to put priority emphasis on primary and secondary cancer prevention.

Declarations of interest

None.

Funding sources

None.

References

- 1.OECD/EU; Paris: 2016. Health at a Glance: Europe 2016: State of Health in the EU Cycle. [Google Scholar]

- 2.European Union; Luxembourg: 2017. Sustainable Development in the European Union. Monitoring Report on Progress Towards the sdgs in an EU Context. [Google Scholar]

- 3.European Union; Brussels: 2018. ECIS – European Cancer information System; Estimates of Cancer Incidence and Mortality in 2018, for All Countries.https://ecis.jrc.ec.europa.eu [updated 02/02/2018. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 4.Islami F., Goding Sauer A., Miller K.D., Siegel R.L., Fedewa S.A., Jacobs E.J., McCullough M.L., Patel A.V., Ma J., Soerjomataram I., Flanders W.D., Brawley O.W., Gapstur S.M., Jemal A. Proportion and number of cancer cases and deaths attributable to potentially modifiable risk factors in the United States. CA: Cancer J. Clin. 2018;68(Jan. (1)):31–54. doi: 10.3322/caac.21440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parkin D.M., Boyd L., Walker L.C. 16. The fraction of cancer attributable to lifestyle and environmental factors in the UK in 2010. Br. J. Cancer. 2011;105(Suppl. 2):S77–S81. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schuz J., Espina C., Villain P., Herrero H., Leon M.E., Minozzi S., Romieu I., Segnan N., Wardle J., Wiseman M., Belardelli F., Bettcher D., Cavalli F., Galea G., Lenoir G., Martin-Moreno J.M., Nicula F.A., Olsen J.H., Patnick J., Primic-Zakelj M., Puska P., van Leeuwen F.E., Wiestler O., Zatonski W., Working Groups of Scientific Experts European code against cancer 4th edition: 12 ways to reduce your cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol. 2015;39(Suppl. 1):S1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2015.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.second ed. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2002. National Cancer Control Programmes: Policies and Managerial Guidelines. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin-Moreno J.M., Alfonso-Sanchez J.L., Harris M., Lopez-Valcarcel B.G. The effects of the financial crisis on primary prevention of cancer. Eur. J. Cancer. 2010;46(14):2525–2533. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin-Moreno J.M., Anttila A., von Karsa L., Alfonso-Sanchez J.L., Gorgojo L. Cancer screening and health system resilience: keys to protecting and bolstering preventive services during a financial crisis. Eur. J. Cancer. 2012;48(14):2212–2218. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.02.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Atun R., Ogawa T., Martin-Moreno J.M. Imperial College London, Business School; London: 2009. Analysis of National Cancer Control Programmes in Europe. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jelenc M., Albreht T., Budewig K., Fitzpatrick P., Modrzynska A., Schellevis F., Zakotnik B., Weiderpass E. European Comission; Brussels: 2017. Policy Paper on National Cancer Control Programmes (NCCPs)/Cancer Documents in Europe. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gorgojo L., Harris M., Garcia-Lopez E. 2013. National Cancer Control Programmes: Analysis of Primary Data From Questionnaires. [Google Scholar]

- 13.ICCP . International Cancer Control Partnership (ICCP); 2018. Portal – the One-stop Shop Online Resource for Cancer Planners.http://www.iccp-portal.org/ [Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization; Geneva: 2018. Noncommunicable Disease Document Repository.https://extranet.who.int/ncdccs/documents/Db [Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 15.European Partnership for Action Against Cancer (EPAAC) European Commission; Brussels: 2011. National Cancer Plans.http://www.epaac.eu/national-cancer-plans [Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ministry of Health of Romania; 2016. The First Integrated Multi-Annual National Cancer control Plan in Romania for 2016–2020. [press release] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ministry of Health; 2017. The National Cancer Plan for the Maltese Islands 2017–2021. [Google Scholar]

- 18.2017. The National Cancer Control Programme 2017–2021. Republika Slovenija. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Danish Centre for Evaluation and Health Technology Assessment; Copenhagen: 2004. Summary and Proposals for Focus Areas: Evaluation of the the Danish National Cancer action Plan – Status and Future Monitoring. [Google Scholar]

- 20.2016. Achieving World-Class Cancer outcomes: A Strategy for England 2015–2020. One Year on 2015–16. [Google Scholar]

- 21.2017. Achieving World-Class Cancer outcomes: A Strategy for England 2015–2020. Progress Report 2016–17. [Google Scholar]

- 22.2015. Évaluation de 10 ans de politique de lutte contre le cancer 2004 - 2014. Paris. [Google Scholar]

- 23.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; Solna, Sweden: 2017. Vaccine Scheduler.https://vaccine-schedule.ecdc.europa.eu/ [updated 2017. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 24.Armaroli P., Villain P., Suonio E., Almonte M., Anttila A., Atkin W.S., Dean P.B., de Koning H.J., Dillner L., Herrero R., Kuipers E.J., Lansdorp-Vogelaar I., Minozzi S., Paci E., Regula J., Tornberg S., Segnan N. European code against cancer, 4th edition: cancer screening. Cancer Epidemiol. 2015;39(Suppl. 1):S139–52. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2015.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Basu P., Ponti A., Anttila A., Ronco G., Senore C., Vale D.B., Segnan N., Tomatis M., Soerjomataram I., Primic Zakelj M., Dillner J., Elfstrom K.M., Lonnberg S., Sankaranarayanan R. Status of implementation and organization of cancer screening in the European Union Member States-Summary results from the second European screening report. Int. J. Cancer. 2018;142(1):44–56. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Official Journal of the European Union; Brussels: 2003. Council Recommendation of 2 December 2003 on Cancer Screening (2003/878/EC) [Google Scholar]

- 27.von Karsa L., Anttila A., Ronco G., Ponti A., Malila N., Arbyn M., Segnan N., Castillo-Beltran M., Boniol M., Ferlay J., Hery C., Sauvaget C., Voti L., Autier P. 2008. Cancer Screening in the European Union. Report on the Implementation of the Council Recommendation on Cancer Screening. First Report. Brussels. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feliu A., Filippidis F.T., Joossens L., Fong G.T., Vardavas C.I., Baena A. Impact of tobacco control policies on smoking prevalence and quit ratios in 27 European Union countries from 2006 to 2014. Tob. Control. 2018;0:1–9. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-054119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Exarchakou A., Rachet B., Belot A., Maringe C., Coleman M.P. Impact of national cancer policies on cancer survival trends and socioeconomic inequalities in England, 1996–2013: population based study. BMJ. 2018;360:k764. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mackenbach J.P., McKee M. A comparative analysis of health policy performance in 43 European countries. Eur. J. Publ. Health. 2013;23(2):195–201. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cks192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies WHO, editor. Successes and Failures of Health Policy in Europe Four Decades of Divergent Trends and Converging Challenges. Open University Press; Berkshire, England: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bull E.R., Dombrowski S.U., McCleary N., Johnston M. Are interventions for low-income groups effective in changing healthy eating, physical activity and smoking behaviours? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2014;4(11) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]