Abstract

Aims

SNF472 is a calcification inhibitor being developed for the treatment of cardiovascular calcification in haemodialysis (HD) and in calciphylaxis patients. This study investigated the safety, tolerability and pharmacokinetics (PK) of intravenous (IV) SNF472 in healthy volunteers (HV) and HD patients.

Methods

This is a first‐time‐in‐human, double‐blind, randomized, placebo‐controlled Phase I study to assess the safety, tolerability and PK of SNF472 after ascending single IV doses in HV and a single IV dose in HD patients. A pharmacodynamic analysis was performed to assess the capability of IV SNF472 to inhibit hydroxyapatite formation.

Results

Twenty HV and eight HD patients were enrolled. The starting dose in HV was 0.5 mg kg–1 and the dose ascended to 12.5 mg kg–1. The dose selected for HD patients was 9 mg kg–1. Safety analyses support the safety and tolerability of IV SNF472 in HD patients and HV. Most treatment‐emergent adverse events were mild in intensity. No clinically significant effects were observed on vital signs or laboratory tests. PK results were similar in HD patients and HV and indicate a lack of significant dialysability. Pharmacodynamic analyses demonstrated that SNF472 administration reduced hydroxyapatite crystallization potential in HD patients who received IV SNF472 9 mg kg–1 by 80.0 ± 2.4% (mean ± standard error of the mean, 95% CI, 75.3–84.8) compared to placebo (8.7 ± 21.0%, P < 0.001, 95% CI, –32.4 to 49.7).

Conclusion

The results from this study showed acceptable safety and tolerability, and lack of significant dialysability of IV SNF472. It is a potential novel treatment for cardiovascular calcification in end‐stage renal disease and calciphylaxis warranting further human studies.

Keywords: cardiovascular calcification, end‐stage renal disease, haemodialysis, hydroxyapatite, phytate, SNF472

What is Already Known about this Subject

Survival in haemodialysis (HD) patients is correlated with cardiovascular calcification (CVC), but no drug for the treatment of CVC has been approved to date. SNF472 is a new calcification inhibitor with reported efficacy in preclinical models. It is being developed for the treatment of CVC in HD and calciphylaxis patients.

What this Study Adds

This is a first‐time‐in‐human, double‐blind, randomized, placebo‐controlled study to assess the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of intravenous SNF472 in healthy volunteers and in HD patients. Our results support the safety, tolerability and potential efficacy of intravenous SNF472 as a novel treatment for CVC and provide a strong rationale for further clinical development.

Introduction

Cardiovascular calcification (CVC) is a major health concern in patients with end‐stage renal disease (ESRD) undergoing haemodialysis (HD). Several studies have shown a correlation between the degree and rate of progression of CVC and cardiovascular events (including mortality) in the general population and patients with chronic kidney disease 1, 2, 3. For HD patients above 60 years, mean life expectancy is <4.5 years in the USA 4, and survival is strongly correlated with the degree of calcification 5. The rate of progression of vascular calcification appears to be an important risk factor as most of the cardiovascular events occur in patients with the fastest progression 2. Cutaneous vascular calcification can result in calciphylaxis, a rare condition with high mortality. The overall mortality in calciphylaxis patients with ESRD is 60–80%, with a 45% 1‐year survival and a 35% 5‐year survival 6, 7.

Strategies to control calcium and phosphate levels (dietary manipulation, managing vitamin D status and drug therapy) in patients with ESRD are integral components of the management of ESRD. No drug has, however, been approved to date, specifically for the treatment of CVC. Currently available drug treatments include vitamin D, phosphate binders and calcimimetics. The ADVANCE study suggested that http://www.guidetopharmacology.org/GRAC/LigandDisplayForward?ligandId=3308 attenuates vascular calcification progression in HD patients 8. The use of sevelamer is associated with slower progression of CVC and a significant survival benefit, in contrast to calcium‐containing phosphate binders 9, 10, 11. The formation and growth of calcium crystals is believed to be the common final mechanism of CVC. Therefore, novel therapies that block the formation and growth of these crystals, are a promising area of investigation for the treatment/prevention of CVC in HD patients.

SNF472 is a selective calcification inhibitor being investigated as a new approach for the treatment of CVC in patients with ESRD undergoing HD and for the treatment of calciphylaxis. It is an intravenous (IV) formulation of myo‐inositol hexaphosphate (IP6), which is a naturally‐occurring substance with beneficial properties in calcium‐related diseases 12, 13, 14, 15. Epidemiological data show a negative correlation between physiological IP6 levels and the occurrence of CVC. A high dietary intake of IP6 has been associated with a lower incidence of cardiac valve calcification 16. Our hypothesis is that SNF472 is able to slow the process of CVC by blocking the formation and growth of hydroxyapatite (HAP) crystals in the blood vessels 17. In contrast to current treatments, SNF472 has the potential to treat CVC by acting directly on the common final mechanism of the calcification pathway.

This paper reports the first‐time‐in‐human study of IV SNF472. The objectives of the present study were to assess the safety, tolerability and pharmacokinetics (PK) of single ascending IV doses of SNF472 in healthy volunteers (HV), and of a single IV dose of SNF472 in HD patients. Additionally, an ex vivo exploratory pharmacodynamics (PD) analysis assessed the capability for SNF472 to inhibit HAP formation.

Methods

This study was conducted at three sites in the UK (Northwick Park Hospital, Hammersmith Hospital and Salford Royal Hospital) in accordance with the International Council for Harmonization E6 Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki. This study is registered at EudraCT (Identifier 2013–005125‐23) and was approved by the National Research Ethics Service and the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects prior to the start of the study.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria for enrolment

HV were males aged 18–45 years. At the time of screening, they were free from any clinically significant illness or disease as determined by medical history, physical examination, safety laboratory test results and other assessments. Subjects had a body mass index ≥19 and ≤ 30 kg m–2. There were no clinically relevant abnormalities of laboratory tests as judged by the investigator. This included no significant liver impairment defined as aspartate aminotransferase or alanine aminotransferase 1.5× upper limit of normal; no significant kidney impairment defined as serum creatinine 1.5× upper limit of normal; no abnormal thyroid function as defined by thyroid stimulating hormone and total thyroxin >5% outside the normal laboratory ranges; or clinically significant calcium and phosphorus values outside the normal range. HV included in the study had no clinically significant abnormalities in 12‐lead electrocardiogram (ECG) as judged by the investigator.

HD patients were males aged 45–75 years, with a reasonably stable health status as judged by the principal investigator. At screening they were all undergoing standard HD three times per week for >1 year and had alkaline phosphatase levels <240 IU l–1.

Study design

This was a Phase 1, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, first‐time‐in‐human study to assess the safety, tolerability and PK/PD of IV SNF472 administered as single ascending doses in HV and of a single IV dose in HD patients. The study consisted of two consecutive parts:

Single ascending dose cohorts (Cohorts 1 and 2) with healthy male volunteers

Single dose cohort with male HD patients

The single ascending dose study in cohorts of HV included a screening visit (within 28 days before the first administration of the study drug), two treatment periods, each consisting of an in‐house stay of 3 nights and 4 days. A follow‐up visit was scheduled 7 ± 2 days after the last ambulatory visit in the second treatment period. The maximum expected study duration for an individual subject in this part of the clinical study, including screening and follow up, was approximately 7 weeks. Subjects received a single IV dose of either SNF472 or placebo infused over a 4‐h period in the morning of day 1 of each treatment period, under fasting conditions. Safety monitoring (vital signs, 12‐lead ECG and safety laboratory assessments), serial blood and urine samples for PK were obtained at specific time points during the treatment periods. During the treatment periods, extensive ECG assessments were done. Subjects were monitored for hypocalcaemia by assessing clinical vital signs and measuring calcium levels in blood.

For HV assessments, Cohort 1 and Cohort 2 were interlocking cohorts with treatment periods alternating between the cohorts (Table S1). Successive treatment periods between Cohort 1 and Cohort 2 were separated by at least 7 days. All the treatment periods started with two sentinel subjects (one placebo and one SNF472‐treated). If no severe adverse effects were detected after the first 24 h, the remaining subjects of the cohort (one placebo and five SNF472‐treated) were treated the following day. Dosing in Cohort 1 started at 0.5 mg kg–1 SNF472 in the first treatment period. Progression to higher doses and dose selection were based on the safety, tolerability and available PK data from predose to 24 h post dose for all subjects from the previous dose level. If it was not appropriate to escalate the dose according to the proposed dose escalation schedule, the same dose or an alternate dose was administered following a Dose Escalation Safety Committee (DESC) meeting. The four treatment periods were: Cohort 1, Treatment Period 1 (dose 0.5 mg kg–1); Cohort 2, Treatment Period 1 (dose 5 mg kg–1); Cohort 1, Treatment Period 2 (dose 9 mg kg–1); and Cohort 2, Treatment Period 2 (dose 12.5 mg kg–1).

The study in HD patients was performed after evaluating all safety, tolerability and PK data from dosing HV. The dose selected for administration to HD patients was 9 mg kg–1 SNF472.

Assessments in HD patients consisted of a screening visit, a single treatment period and a follow‐up visit. The maximum planned study duration for each patient, including screening and follow up, was approximately 6 weeks. The food allowed was in accordance with the dietary requirements for HD patients. On Day 1, patients received a single infusion into the dialysis tubing of either 9 mg kg–1 of SNF472 or placebo over a 4‐h period during the patient's dialysis session. The study drug was administered during the second or third dialysis session of the week so that all subjects were treated 48 h after the previous dialysis session. Safety monitoring (vital signs, extensive 12‐lead ECGs, and safety laboratory assessments), and serial blood samples for PK were collected at specific time points during the treatment period. Patients were monitored throughout the study for signs or symptoms of hypocalcaemia.

Treatments

SNF472 is an IV formulation of the hexasodium salt of IP6. Study drug was provided as a 5‐ml sterile solution containing 100 mg of SNF472 (Almac, Craigavon, United Kingdom).

For study drug administration, a 20‐mg ml–1 solution of SNF472 was diluted into an appropriate volume of saline in order to infuse the correct concentration of the SNF472 per body weight of each subject. The starting dose selected was 0.5 mg kg–1 SNF472. The planned dose levels for the subsequent doses in HV were 1.5, 5 and 10 mg kg–1 SNF472. Progression to the higher dose level(s) and dose selection were based on the safety, tolerability and available PK data from the previous dose level(s). Doses were given in two different infusion volumes, 50 ml (for 0.5 and 5 mg kg–1 doses) and 1000 ml (for 9 and 12.5 mg kg–1 doses) during 4‐h infusion.

Following administration of 0.5 mg kg–1 SNF472, all PK samples were below the lower limit of quantification of 0.5 μg ml–1. The DESC decided that the next dose administered should be 5 mg kg–1 during Treatment Period 1 (Cohort 2). The dose chosen was 12.5 mg kg–1 during Treatment Period 2 (Cohort 1). The next dose was reduced to 9 mg kg–1 SNF472 during Treatment Period 2 (Cohort 2) due to vascular irritation at the injection site at 12.5 mg kg–1 (Table S1).

The dose selected for HD patients was 9 mg kg–1 SNF472 to compare with the same dose used in HV. This dose was determined after all safety, tolerability and PK data from HV were evaluated.

For placebo administration, a saline solution (0.9% NaCl) was administered at appropriate volumes and time periods.

PK and PD assessments

Blood samples for PK analysis of SNF472 were collected up to 72 h postdose. The actual date and time of each blood sample collected was recorded. The sampling time points were subject to change after review of PK data from lower dose treatment periods. For interim analyses, data were provided in the form of a PK report to the sponsor and principal investigator between dose levels and to the DESC in order to facilitate dose selection for the following dose to HV. For dose selection for HD patients, the DESC assessed all the data from the HV (provided using alias subject numbers to preserve blinding). A PK stopping criterion of maximum SNF472 concentration measured in plasma (Cmax) of 127.3 μg ml–1 was established.

The PK parameters calculated were: AUC(0➔t) (area under the curve from 0 to the time of the last quantifiable concentration), AUC(inf) (area under the curve from 0 to infinity), %AUCex (percentage of AUC extrapolated from AUC(0➔t)), CL (total body clearance), Cmax (maximum SNF472 concentration measured in plasma), t1/2 (terminal elimination half‐life), tmax (time at which the Cmax is measured), Vz (volume of distribution at terminal phase) and λz (apparent first order terminal elimination rate constant).

The dialysability of SNF472 was assessed by comparing the AUC(0‐t) t (area under the curve from 0 to the time of the last quantifiable concentration) and Cmax from HD patients, to the 9 mg kg–1 dose tested in HV.

Urine was collected for a 48‐h period at predose, 0–4 h, 4–8 h, 8–12 h, 12–24 h and 24–48 h postdose).

Blood for PK analysis was collected into K3EDTA anticoagulant tubes, centrifuged at 1500 × g for 10 min at 4°C and plasma stored at –80°C pending phytic acid quantification by ultrahigh‐performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry using the validated method described by Tur et al. 18.

Aliquots from the plasma samples collected at baseline and around the tmax from all subjects were used for exploratory PD assessment 19. The PD spectrophotometric assay was performed in 96‐well plates. Plasma (80 μl) was centrifuged at 10 000 × g for 30 min at room temperature and subsequently mixed with 60 μl of 5 mmol l–1 hydrogen phosphate and 60 μl of 41.67 mmol l–1 calcium to attain final concentrations of 1.5 mmol l–1 phosphate and 12.5 mmol l–1 calcium, respectively. All reagent solutions were filtered and pH adjusted to 7.4. Crystallization of calcium phosphate aggregates was monitored spectrophotometrically for 30 min at room temperature by determining the increase in absorbance at 550 nm using the Biotek Powerwave XS Microplate spectrophotometer. The plate was incubated at room temperature in an orbital shaker (750 rpm) and absorbance measured every 3 min. Plasma crystallization potential was assessed by slope measurement in the linear range between 6 and 24 min from plots of increase in absorbance vs. logarithm of time. Inhibition of crystallization was measured by comparing the slopes of the baseline samples with those of tmax samples as shown below:

| (1) |

Safety assessments

Safety parameters included adverse events (AEs), clinical laboratory [haematology, clinical chemistry (including plasma electrolytes), urinalysis and coagulation (HV only)], vital signs (pulse, respiratory rate, supine blood pressure, and oral body temperature), 12‐lead ECG parameters (cardiac intervals, PR, QRS, QT and QTc), and physical examination. Hypocalcaemia was monitored by measuring ionized calcium levels up to 24 h postinfusion.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using the SAS Version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Plasma SNF472 PK parameters were calculated by noncompartmental analysis from the concentration–time data. The PK parameters were assessed using descriptive statistics and were summarized using arithmetic mean, standard deviation (SD), coefficient of variation (CV), median, minimum, maximum, geometric mean and number of observations. PK concentration data were summarized by nominal time‐point and dose level. All original and derived PK and safety parameters, as well as population characteristics, were listed and described using summary statistics.

Dose proportionality was assessed using a power model for SNF472 Cmax, AUC(0‐t), and AUC(inf).

loge (AUC or Cmax) = μ + β × loge (Dose) or (where loge is the natural logarithm)

AUC (or Cmax) = eμ × Doseβ

The estimate obtained for β is a measure of dose proportionality.

In general, demographic data and other relevant baseline characteristics were summarized by cohort; safety data were summarized by treatment group. Subjects who received placebo were pooled by subject population, i.e. HV or HD patients. Comparisons between screening and follow‐up assessments were summarized for all patients.

Numerical variables in demographic and baseline characteristics were summarized by displaying: n (nonmissing sample size), mean, SD, standard error, median, quartiles, 10th and 90th percentiles, maximum, and minimum. The CV was added when considered appropriate. The frequency and percentages (based on n) of observed levels were reported for all categorical measures. Percentages were calculated using the total number of subjects per group.

For the PD measurements, a Student t test was performed comparing the results obtained in the placebo group vs. the SNF472‐treated group, and a P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Nomenclature of targets and ligands

Key ligands in this article are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 20, and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2017/18.

Results

Patients and treatment

The endpoints of this study were evaluated in two consecutive parts, consisting of study assessments in HV followed by assessments in HD patients.

A total of 16 male HV were randomized and arranged into two cohorts. Within each cohort, subjects were randomized in a 6:2 ratio to receive either SNF472 or placebo. HV were recruited for two treatment doses. Three subjects who completed their first treatment, prematurely withdrew from Cohort 1 as well as two subjects from Cohort 2. They withdrew as they were not available at the planned date of their second participation. These subjects were replaced by two subjects for each cohort. A total of eight male HD patients were randomized and treated. HD patients were also randomized in a 6:2 ratio to receive either SNF472 or placebo. All the HD patients completed the study.

Demographic characteristics were similar in both cohorts of HV (Table 1). The HD patients were older (due to increased age range for inclusion), weighed more and had a higher body mass index on average than the HVs. The majority of HD patients were white (87.5%).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics

| Characteristic | Statistic | Healthy volunteers | Haemodialysis patients (n = 8) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort 1 (n = 10) | Cohort 2 (n = 10) | ||||||

| Age (years) | Mean | 32.1 | 29.9 | 57.6 | |||

| Range | 26.0–44.0 | 20.0–45.0 | 46.0–66.0 | ||||

| Weight (kg) | Mean | 78.8 | 76.6 | 93.2 | |||

| Range | 65.7–91.1 | 59.2–88.8 | 68.2–122.8 | ||||

| Body mass index (kg m –2 ) | Mean | 24.7 | 24.1 | 30.3 | |||

| Range | 20.8–28.4 | 19.6–26.8 | 23.1–41.0 | ||||

| Ethnic origin | |||||||

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 10 | 100.0 | 10 | 100.0 | 8 | 100.0 | |

| Race | |||||||

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 2 | 20.0 | 2 | 20.0 | 1 | 12.5 | |

| Black or African American | 1 | 10.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Mixed | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 20.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| White | 7 | 70.0 | 6 | 60.0 | 7 | 87.5 | |

PK

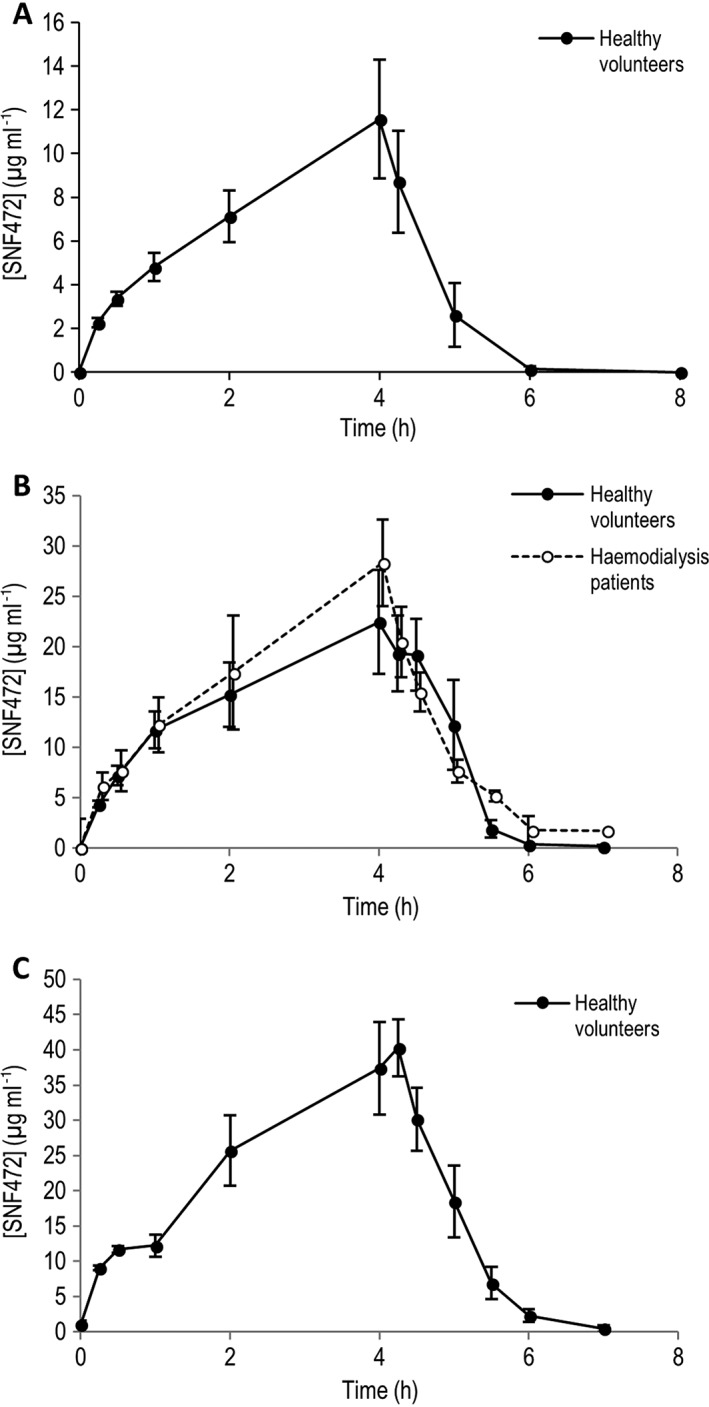

The PK stopping criterion (Cmax of 127.3 μg ml–1) was not met for any of the subjects. Cmax and AUC parameters increased in a slightly more than dose proportional manner (Figure 1). The arithmetic means and SD of Cmax and AUC are shown in Table 2 . For the 0.5 mg kg–1 dose level, all samples analysed were below the lower limit of quantification of 0.5 μg ml–1. Following a single IV dose of 9 mg kg–1 in HD patients, Cmax and AUC were similar to the values observed for the equivalent dose in HV.

Figure 1.

Pharmacokinetic profile of intravenous SNF472 in healthy volunteers and haemodialysis patients. (A) 5 mg kg–1, (B) 9 mg kg–1, (C) 12.5 mg kg–1. Results represent mean ± standard deviation

Table 2.

Summary of plasma pharmacokinetic parameters

| A. Healthy volunteers | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | tmax (min) | Cmax (μg ml–1) | AUC0‐t (μg*h ml–1) | AUC0‐inf (μg*h ml–1) | %AUCex (%) | λz (1/h) | t1/2 (min) | Vz (ml) | CL ( ml h–1) |

| Cohort 2 treatment period 1: 5 mg kg –1 | |||||||||

| N | 6 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Mean | 240 | 11.6 | 34.8 | 42.5 | 2.8 | 1.8 | 24 | 6339 | 11 679 |

| SD | 1 | 6.7 | 19.4 | 20.6 | 2.1 | 0.3 | 4 | 2244 | 6125 |

| 95% CI | 239–241 | 6.2–17.0 | 19.3–50.3 | 22.3–62.7 | 0.74–4.86 | 1.51–2.09 | 20–28 | 4140–8538 | 5677–17 681 |

| Cohort 2 treatment period 2: 9 mg kg –1 | |||||||||

| N | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Mean | 214 | 24.4 | 83.7 | 89.9 | 9.0 | 1.2 | 54 | 12 446 | 8749 |

| SD | 76 | 11.5 | 48.7 | 44.0 | 18.5 | 0.5 | 59 | 16 516 | 3451 |

| 95% CI | 153–275 | 15.2–33.6 | 44.7–123 | 54.7–125 | –5.80‐23.8 | 0.80–1.60 | 6.79–101 | 0–25 661 | 5988–11 510 |

| Cohort 1 treatment period 2: 12.5 mg kg –1 | |||||||||

| N | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Mean | 252 | 42.2 | 132.2 | 133.7 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 29 | 5832 | 8493 |

| SD | 8 | 10.8 | 42.2 | 42.5 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 8 | 2316 | 3066 |

| 95% CI | 245–259 | 32.7–51.7 | 95.2–169 | 96.4–171 | 0.50–1.90 | 1.15–1.85 | 22.0–36.0 | 3802–7862 | 5806–11 180 |

| B. Haemodialysis patients | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | tmax (min) | Cmax (μg ml–1) | AUC0‐t (μg*h ml–1) | AUC0‐inf (μg*h ml–1) | %AUCex (%) | λz (1/h) | t1/2 (min) | Vz (ml) | CL (ml h–1) |

| N | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Mean | 225 | 29.0 | 92.0 | 93.0 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 27 | 6607 | 10 567 |

| SD | 60 | 13.9 | 34.3 | 35.0 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 6 | 1230 | 2570 |

| 95% CI | 172–278 | 16.8–41.2 | 61.9–122 | 62.3–124 | 0.56–1.44 | 1.34–1.86 | 21.7–32.3 | 5529–7685 | 8314–12 820 |

AUC(0➔t), area under the curve from 0 to the time of the last quantifiable concentration; AUC(inf), area under the curve from 0 to infinity; %AUCex, percentage of AUC extrapolated from AUC(0➔t); CL, total body clearance; Cmax, maximum SNF472 concentration measured in plasma; t1/2, terminal elimination half‐life; tmax, time at which the Cmax is measured; Vz, volume of distribution at terminal phase; λz, apparent first order terminal elimination rate constant); CI, confidence interval

The median tmax was approximately 4 h (infusion time) for each treatment group. The mean t½ ranged from 24 to 54 min in HV and was 27 min in HD patients. Steady state was not achieved at the end of infusion at any dose.

The arithmetic mean CL was consistent for the 9 and 12.5 mg kg–1 dose levels, with CL values of 11.7, 8.7 and 8.5 l h–1 for the 5, 9 and 12.5 mg kg–1 dose levels, respectively. The CL for HD patients (9 mg kg–1 dose) was 10.6 l h–1.

The total amount of SNF472 excreted in urine accounted for <1% of the total administered dose in HV. No urine samples were collected for HD patients.

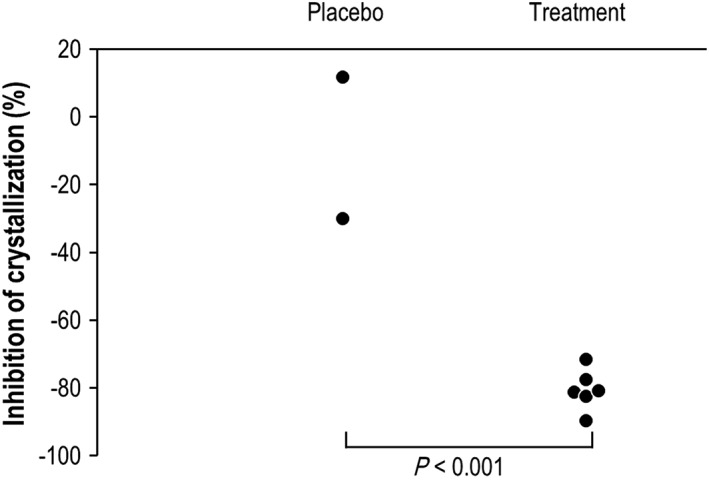

PD

The ex vivo HAP crystallization rate in plasma was used as a PD measurement for a preliminary evaluation of the potential effect of SNF472 on CVC. This PD assay used plasma samples for determining the effect of SNF472 on blood calcification propensity. SNF472 administration reduced HAP crystallization potential significantly in HD patients who received IV SNF472 9 mg kg–1 by 80.0 ± 2.4% (mean ± SEM, 95% CI, 75.3–84.8; Figure 2) compared to placebo (8.7 ± 21.0%, P < 0.001, 95% CI, –32.4‐49.7).

Figure 2.

Inhibition of induction of hydroxyapatite crystallization in plasma samples in haemodialysis patients after intravenous infusion of SNF472 or placebo. Statistical analysis: Student t test, P ≤ 0.001

Safety

No serious AEs, deaths, or withdrawals due to AEs were reported during the study for HV or HD patients.

In HV, the number of subjects who reported treatment‐emergent adverse events (TEAEs) was slightly higher in the SNF472 treatment groups compared with the placebo group. The number of subjects who reported TEAEs was similar amongst the SNF472 dose groups (Table 3 ). The majority of TEAEs were mild in intensity, with some moderate intensity TEAEs reported for the 5 and 12.5 mg kg–1 SNF472 doses. The majority of TEAEs were in the system organ class of general disorders and administration site conditions (infusion site pain, infusion site erythema, infusion site hypoesthesia and infusion site swelling), all of which were probably related to the study drug. Infusion site pain was the most commonly reported TEAE. Other related TEAEs include injection site bruising, headache, dizziness, pain in extremity, myalgia and injury of the eye‐lid (bruising of the upper left eye‐lid), which were considered possibly related to the study drug in the investigator's opinion.

Table 3.

Summary of treatment‐emergent adverse events (TEAEs) by system organ class and preferred term

| System organ class | Placebo | 0.5 mg kg–1 | 5.0 mg kg–1 | 9.0 mg kg–1 | 12.5 mg kg–1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred term | N = 8 | N = 6 | N = 6 | N = 6 | N = 5 |

| Healthy volunteers (Cohorts 1 and 2) | N [n] | N [n] | N [n] | N [n] | N [n] |

| Any TEAE | 4 [7] | 5 [16] | 5 [14] | 6 [8] | 5 [11] |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | |||||

| Infusion site pain | 0 | 4 [4] | 5 [8] | 3 [3] | 4 [6] |

| Infusion site erythema | 1 [1] | 1 [2] | 1 [1] | 3 [3] | 1 [1] |

| Infusion site bruising | 0 | 2 [2] | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Infusion site hypoaesthesia | 0 | 0 | 2 [2] | 0 | 0 |

| Catheter site pain | 1 [1] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Feeling of body temperature change | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 [1] |

| Infusion site swelling | 0 | 1 [1] | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Malaise | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 [1] |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | |||||

| Pain in extremity | 1 [1] | 0 | 1 [1] | 1 [1] | 0 |

| Myalgia | 1 [1] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 [1] |

| Musculoskeletal pain | 1 [1] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nervous system disorders | |||||

| Headache | 0 | 3 [5] | 0 | 0 | 1 [1] |

| Dizziness | 0 | 0 | 1 [1] | 1 [1] | 0 |

| Somnolence | 0 | 0 | 1 [1] | 0 | 0 |

| Immune system disorders | |||||

| Seasonal allergy | 1 [1] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Injury, poisoning and procedural complications | |||||

| Eyelid injury | 0 | 1 [1] | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders | |||||

| Dry throat | 1 [1] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | |||||

| Miliaria | 0 | 1 [1] | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| System organ class | Placebo | 9.0 mg kg–1 |

|---|---|---|

| Preferred term | N = 2 | N = 6 |

| Haemodialysis patients | N [n] | N [n] |

| Any TEAE | 1 [1] | 3 [6] |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | ||

| Paraesthesia oral | 0 | 1 [2] |

| Vomiting | 1 [1] | 0 |

| Infections and infestations | ||

| Cellulitis | 0 | 1 [1] |

| Nasopharyngitis | 0 | 1 [1] |

| Cardiac disorders | ||

| Palpitations | 0 | 1 [1] |

| Vascular disorders | ||

| Hypertension | 0 | 1 [1] |

N, number of subjects; n, number of episodes

In HD patients, one event was reported in the placebo group compared to six events in the treated group. The majority of possibly related TEAEs were in the system organ class of gastrointestinal disorders: one subject reported two events of oral paresthaesia (both episodes were mild in intensity). The only other possibly related TEAE was hypertension (one event reported for the SNF472 group), which was moderate in intensity. All other TEAEs were assessed as either unlikely related or not related to the study drug and were mild in intensity.

No clinically relevant changes were observed in clinical laboratory tests, 12‐lead ECGs, physical examinations, visual analogue scale tests, and orthostatic hypotension tests. A potential dose‐dependent reduction of ionized calcium was observed following SNF472 administration in HV. A modest reduction in ionized calcium was observed in the 12.5 mg kg–1 dose group at 2, 4 and 6 h post‐infusion (1.06, 1.01 and 1.09 mmol l–1, respectively) compared with placebo (1.24, 1.21 and 1.18 mmol l–1, respectively). However, there were no clinical features of hypocalcaemia and no clinically relevant increases in QTc. This effect resolved within 12 h (1.18 mmol l–1 in SNF472 12.5 mg kg–1 and 1.16 mmol l–1 in placebo); total calcium was unchanged. In the HD patients treated with SNF472, no changes were noted in ionized calcium values at any time point compared with baseline (baseline: 1.20 mmol l–1, 2 h: 1.21 mmol l–1, 4 h: 1.28 mmol l–1, 6 h: 1.16 mmol l–1) or placebo treatment. There were no clinical features of hypocalcaemia observed and no clinically relevant increases in QTc.

Concentration‐dependent instances of local irritation that resolved within 24 h were observed in HV. This effect was not seen in HD patients since the drug was premixed and diluted within the blood in the dialysis machine prior to reaching the body.

Discussion

SNF472 is being investigated as a treatment to delay the progression of CVC in patients with ESRD who are undergoing HD and for patients with calciphylaxis. This first‐time‐in‐human clinical study evaluated the safety, tolerability and PK profile of IV SNF472 at single ascending doses in HV and of a single IV dose in male HD patients. By comparing the PK of equivalent doses of SNF472 in HD patients to HV, the dialysability of IV SNF472 could be evaluated to support the use of IV SNF472 as a treatment for CVC in this population. Furthermore, a validated ex vivo PD assay using plasma samples was performed to predict the capability for IV SNF472 to inhibit calcium phosphate crystal formation at the doses tested in this study.

PK assessments in HV showed Cmax dose linearity and a relatively short half‐life. As steady state was not achieved during the 4‐h infusion period, and the Vz was close to the plasma volume, it is possible that only the distribution half‐life was seen, and that the terminal half‐life occurs at levels below the lower limit of quantification. The total amount of SNF472 excreted in urine accounted for <1% of the total administered dose in HV. Given the short half‐life and no renal elimination, accumulation is not expected in subsequent studies at repeated doses. Similar plasma levels were found in HD patients when comparing the dose of 9 mg kg–1, demonstrating that SNF472 is not lost via the dialysis membrane. The PK results from this study indicate that IV SNF472 is not significantly dialysed. SNF472 concentrations achieved with 9 mg kg–1 and 12.5 mg kg–1 were around 4‐ and 8‐fold higher that the anticipated therapeutic concentrations.

A PD assay to measure the crystallization potential of blood through the artificial induction of calcium phosphate crystal formation in blood samples was validated in human and rat plasma samples 19. These studies demonstrated that the addition of SNF472 to rat plasma samples ex vivo reduced the HAP crystallization rate (up to 80%), which was comparable to in vivo results that demonstrated a reduction in HAP crystallization potential of plasma by up to 70% following subcutaneous administration of SNF472 to rats. In the current study, administration of 9 mg kg–1 SNF472 in HD patients inhibited ex vivo calcium phosphate crystal formation in plasma by 80.2%. This degree of inhibition is comparable to previous results in rodent models and suggests that IV treatment with SNF472 may be an effective strategy for inhibiting CVC.

IP6 (the active component of SNF472) has been shown to prevent vascular calcification in a variety of animal models 15, 21. This molecule has a high affinity for solid calcium salts, and rapidly binds to the surface of a forming nucleus or on the faces of a growing crystal 22. It acts as an inhibitor of crystallization at sub‐stoichiometric levels, since it specifically binds to the growth sites to block the calcification process and does not require binding to the entire crystal surface. By blocking the growth and formation of calcium deposits, SNF472 inhibits the final common pathway of CVC. This effect is likely to be independent of the aetiology of the CVC and occurs at any plasma calcium or phosphate level 23. Moreover, as a treatment, it could be used at serum concentrations far below free calcium concentrations because the target is not free calcium in solution, but solid calcium being deposited on the vessel walls. Calcium chelation does not occur at therapeutic concentrations of SNF472 and hence the risk of inducing hypocalcaemia is avoided. A recent publication hypothesized that the dietary intake of phytate could attenuate the development of age‐related CVC 17, even at the early stages of chronic kidney disease 24, and the aggressive CVC seen in HD patients could be partially explained by the loss of IP6. Importantly, the dietary regimens prescribed for HD patients reduce the intake of many of the main IP6‐containing foods. As intestinal absorption of IP6 is limited, this deficiency could be counteracted by supraphysiological phytate plasma concentrations achievable by IV administration.

The inhibition of pathological processes of calcification in soft tissue by IP6 is accompanied by a reported positive effect on bone. Two epidemiological studies on 1473 and 180 subjects revealed a correlation between higher bone mineral density and phytate consumption, and physiological phytate levels, respectively 25, 26. Another study on postmenopausal women demonstrated a correlation between high physiological levels of phytate and lower bone mass loss over a 12‐month period 27. In addition, results obtained in toxicology studies in dogs provided evidence that SNF472 has no effect on bone mineralization in healthy dogs (unpublished results).

Safety and toxicology studies in mice, rats, and dogs have shown that IV SNF472 is generally safe and well tolerated (unpublished results). AEs associated with hypocalcaemia (due to chelation), including QTc prolongation, were observed following bolus injections of high doses; however, these effects were transient and were linked to the Cmax. The risk of these effects is minimized by a slow 4‐h infusion of SNF472 that is planned for delivery to HD patients, which avoids the Cmax related side effects. The safety analyses from the current study support the safety and tolerability of SNF472 in HV and HD patients at the doses used. There were no serious AEs, no deaths and no AEs that led to withdrawal from the study. The majority of TEAEs reported in HV were relatively mild transient infusion site reactions. A bruising of the upper left eye‐lid appeared spontaneously without history of trauma in one subject. His clotting profile and platelets at 4 h and 6 h were normal, but relation to the study drug could not be absolutely excluded. As the drug is diluted in the blood in the dialysis system, these reactions were not seen in HD patients.

No clinically significant effects were observed on vital signs or laboratory tests as considered by the investigator or by an independent cardiology review. The decrease in ionized calcium values, only seen in HVs, suggests a possibly a dose‐related decrease with SNF472. However, there were no clinical signs or symptoms of hypocalcaemia reported or clinically relevant increases in QTc observed with any of the doses evaluated. Furthermore, in the intended therapeutic situation (infusion during dialysis), the ionized calcium concentration in the blood is stabilized by the calcium concentration in the dialysis fluid. The risk of hypocalcaemia is therefore minimized by the planned route of drug administration. As the higher doses tested in this study produced plasma concentrations that were significantly higher than the anticipated therapeutic levels, IV SNF472 therapy would probably be at doses well below a dosage that would lead to significant calcium chelation.

The results from this first‐time‐in‐human clinical study support the safety, tolerability and lack of significant dialysability of IV SNF472 as a novel treatment for CVC in ESRD and calciphylaxis and provide a strong rationale for further development of this therapy. The safety, PK, and PD of IV SNF472 are being further evaluated following multiple ascending doses and fixed repeated doses over a prolonged time (28 days) in subsequent clinical studies in HD patients. While the PD results from this study suggest that SNF472 can effectively inhibit CVC in HD patients, the efficacy of IV SNF472 as a treatment for CVC needs to be tested in additional clinical studies. In fact, a Phase 2 open label, single arm, repeat dose study in patients with calciphylaxis has recently finished, while another Phase 2 double‐blind, randomized, placebo‐controlled study to assess the effect of SNF472 on progression of CVC in ESRD patients on HD is ongoing.

Competing Interests

All the authors are employees or have received honoraria from Laboratoris Sanifit SL. J.P., P.H.J., M.D.F., A.Z.C. and C.S. are shareholders at Laboratoris Sanifit SL.

The authors acknowledge the volunteers and patients who participated in this clinical trial, Dr John Lambert and the personnel of the Northwick Park Hospital, Hammersmith Hospital and Salford Royal Hospital for their execution of the clinical trial, the team of Parexel for monitoring the study, the team of ICRC‐Weyer, Marta Rodríguez and Juan Vicente Torres (Syntax for Science) for data management and Ryan Overcash for its assistance on drafting the manuscript.

This study was supported by a grant from Fundación Genoma España/Centro para el Desarrollo Tecnológico Industrial” (CDTI) through the INNOCASH program (IC10‐129). MDF (PTQ‐11‐04860), CS (PTQ‐11‐04872) and AZC (PTQ‐13‐06355) were co‐funded by the INNCORPORA‐Torres Quevedo subprogram of the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad, Government of Spain.

Contributors

J.P., P.H.J. and C.S. designed the study; M.D.F., A.Z.C. and S.S. supervised the study and carried out experiments; J.P., P.H.J, M.D.F., S.S. and C.S. analysed and interpreted the data; all authors drafted and revised the paper and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supporting information

Table S1 Treatment schemes for healthy volunteers and haemodialysis patients

Perelló, J. , Joubert, P. H. , Ferrer, M. D. , Canals, A. Z. , Sinha, S. , and Salcedo, C. (2018) First‐time‐in‐human randomized clinical trial in healthy volunteers and haemodialysis patients with SNF472, a novel inhibitor of vascular calcification. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 84: 2867–2876. 10.1111/bcp.13752.

References

- 1. Budoff MJ, Gul KM. Expert review on coronary calcium. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2008; 4: 315–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Russo D, Corrao S, Battaglia Y, Andreucci M, Caiazza A, Carlomagno A, et al Progression of coronary artery calcification and cardiac events in patients with chronic renal disease not receiving dialysis. Kidney Int 2011; 80: 112–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Coen G, Pierantozzi A, Spizzichino D, Sardella D, Mantella D, Manni M, et al Risk factors of one year increment of coronary calcifications and survival in hemodialysis patients. BMC Nephrol 2010; 11: 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Saran R, Li Y, Robinson B, Abbott KC, Agodoa LY, Ayanian J, et al US Renal Data System 2015 Annual Data Report: epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 2016; 67: Svii, S1–Svii, S305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shantouf RS, Budoff MJ, Ahmadi N, Ghaffari A, Flores F, Gopal A, et al Total and individual coronary artery calcium scores as independent predictors of mortality in hemodialysis patients. Am J Nephrol 2010; 31: 419–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mazhar AR, Johnson RJ, Gillen D, Stivelman JC, Ryan MJ, Davis CL, et al Risk factors and mortality associated with calciphylaxis in end‐stage renal disease. Kidney Int 2001; 60: 324–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Weenig RH, Sewell LD, Davis MD, McCarthy JT, Pittelkow MR. Calciphylaxis: natural history, risk factor analysis, and outcome. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007; 56: 569–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Raggi P, Chertow GM, Torres PU, Csiky B, Naso A, Nossuli K, et al The ADVANCE study: a randomized study to evaluate the effects of cinacalcet plus low‐dose vitamin D on vascular calcification in patients on hemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2011; 26: 1327–1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Block GA, Raggi P, Bellasi A, Kooienga L, Spiegel DM. Mortality effect of coronary calcification and phosphate binder choice in incident hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 2007; 71: 438–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Block GA, Spiegel DM, Ehrlich J, Mehta R, Lindbergh J, Dreisbach A, et al Effects of sevelamer and calcium on coronary artery calcification in patients new to hemodialysis. Kidney Int 2005; 68: 1815–1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chertow GM, Burke SK, Raggi P. Sevelamer attenuates the progression of coronary and aortic calcification in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 2002; 62: 245–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Grases F, March JG, Prieto RM, Simonet BM, Costa‐Bauza A, Garcia‐Raja A, et al Urinary phytate in calcium oxalate stone formers and healthy people – dietary effects on phytate excretion. Scand J Urol Nephrol 2000; 34: 162–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Grases F, Bernat I, Sanchis P, Torres JJ, Costa‐Bauza A. Phytate acts as an inhibitor in formation of renal calculi. Front Biosci 2007; 12: 2580–2587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Grases F, Sanchis P, Prieto RM, Perello J, Lopez‐Gonzalez AA. Effect of tetracalcium dimagnesium phytate on bone characteristics in ovariectomized rats. J Med Food 2010; 13: 1301–1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Grases F, Sanchis P, Perello J, Isern B, Prieto RM, Fernandez‐Palomeque C, et al Phytate (Myo‐inositol hexakisphosphate) inhibits cardiovascular calcifications in rats. Front Biosci 2006; 11: 136–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fernandez‐Palomeque C, Grau A, Perello J, Sanchis P, Isern B, Prieto RM, et al Relationship between urinary level of phytate and valvular calcification in an elderly population: a cross‐sectional study. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0136560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Joubert P, Ketteler M, Salcedo C, Perello J. Hypothesis: Phytate is an important unrecognised nutrient and potential intravenous drug for preventing vascular calcification. Med Hypotheses 2016; 94: 89–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tur F, Tur E, Lentheric I, Mendoza P, Encabo M, Isern B, et al Validation of an LC‐MS bioanalytical method for quantification of phytate levels in rat, dog and human plasma. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 2013; 928: 146–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ferrer MD, Perez MM, Canaves MM, Buades JM, Salcedo C, Perello J. A novel pharmacodynamic assay to evaluate the effects of crystallization inhibitors on calcium phosphate crystallization in human plasma. Sci Rep 2017; 7: 6858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Harding SD, Sharman JL, Faccenda E, Southan C, Pawson AJ, Ireland S, et al The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY in 2018: updates and expansion to encompass the new guide to IMMUNOPHARMACOLOGY. Nucl Acids Res 2018; 46: D1091–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Grases F, Sanchis P, Perello J, Isern B, Prieto RM, Fernandez‐Palomeque C, et al Effect of crystallization inhibitors on vascular calcifications induced by vitamin D: a pilot study in Sprague–Dawley rats. Circ J 2007; 71: 1152–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fernández D, Ortega‐Castro J, Frau J. Theoretical study of the deposition and adsorption of bisphosphonateson the 001 hydroxyapatite surface: implications in the pathological crystallization inhibition and the bone antiresorptive action. Appl Surf Sci 2017; 392: 204–214. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Grases F, Costa‐Bauza A. Phytate (IP6) is a powerful agent for preventing calcifications in biological fluids: usefulness in renal lithiasis treatment. Anticancer Res 1999; 19: 3717–3722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sanchis P, Buades JM, Berga F, Gelabert MM, Molina M, Inigo MV, et al Protective effect of myo‐inositol hexaphosphate (phytate) on abdominal aortic calcification in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Ren Nutr 2016; 26: 226–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lopez‐Gonzalez AA, Grases F, Roca P, Mari B, Vicente‐Herrero MT, Costa‐Bauza A. Phytate (myo‐inositol hexaphosphate) and risk factors for osteoporosis. J Med Food 2008; 11: 747–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lopez‐Gonzalez AA, Grases F, Perello J, Tur F, Costa‐Bauza A, Monroy N, et al Phytate levels and bone parameters: a retrospective pilot clinical trial. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2010; 2: 1093–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lopez‐Gonzalez AA, Grases F, Monroy N, Mari B, Vicente‐Herrero MT, Tur F, et al Protective effect of myo‐inositol hexaphosphate (phytate) on bone mass loss in postmenopausal women. Eur J Nutr 2013; 52: 717–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Treatment schemes for healthy volunteers and haemodialysis patients