Abstract

The industrial application of microorganisms as starters or probiotics requires their preservation to assure viability and metabolic activity. Freezing is routinely used for this purpose, but the cold damage caused by ice crystal formation may result in severe decrease in microbial activity. In this study, adaptive laboratory evolution (ALE) technique was applied to a lactic acid bacterium to select tolerant strains against freezing and thawing stresses. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG was subjected to freeze-thaw-growth (FTG) for 150 cycles with four replicates. After 150 cycles, FTG-evolved mutants showed improved fitness (survival rates), faster growth rate, and shortened lag phase than those of the ancestor. Genome sequencing analysis of two evolved mutants showed genetic variants at distant loci in six genes and one intergenic space. Loss-of-function mutations were thought to alter the structure of the microbial cell membrane (one insertion in cls), peptidoglycan (two missense mutations in dacA and murQ), and capsular polysaccharides (one missense mutation in wze), resulting in an increase in cellular fluidity. Consequently, L. rhamnosus GG was successfully evolved into stress-tolerant mutants using FTG-ALE in a concerted mode at distal loci of DNA. This study reports for the first time the functioning of dacA and murQ in freeze-thaw sensitivity of cells and demonstrates that simple treatment of ALE designed appropriately can lead to an intelligent genetic changes at multiple target genes in the host microbial cell.

Keywords: adaptive laboratory evolution, lactic acid bacteria, Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG, freeze-thaw stress, genome sequencing

Introduction

Live lactic acid bacteria (LAB) have been traditionally consumed through fermented food products and selected Lactobacillus strains that tolerate intestinal conditions have increasingly been used owing to their health effects. These strains, termed as “probiotics,” are described as live well-defined microorganisms with beneficial effects on wellbeing of the host (Hill et al., 2014). Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (ATCC 53103) was originally isolated from the fecal samples of healthy human intestinal flora (Goldin et al., 1992). This strain possessed general characteristics of probiotics, such as tolerance to acid and bile and the ability to adhere to the intestinal epithelial layer. In addition, its diverse beneficial effects on human health, including improved intestinal health and immune systems were reported (Segers and Lebeer, 2014). Clinical treatment of L. rhamnosus GG showed preventive or therapeutic effects on pathogen infection such as Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Salmonella Infantis (Johnson-Henry et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2018). Besides, the strain exhibited anti-cancer properties and mitigated the side effect of cancer therapy like diarrhea (Banna et al., 2017). These outstanding features of L. rhamnosus GG have encouraged its microbial studies and wide use in the industrial production of probiotic products for nearly 30 years.

The industrial exploitation and applications of LAB as starters or probiotic strains require efficient preservation technologies to maintain the viability and probiotic activities of these bacteria (Carvalho et al., 2004). Freezing preservation or freeze drying operations are widely used for the long-term storage of LAB but often negatively affect their viability (Rault et al., 2007). Exposure to low temperature and subsequent ice crystallization during freezing process are stressful to the cells. Ice crystal formation first occurs in the extracellular spaces. The withdrawal of water from the system creates a hyperosmotic extracellular environment, which in turn draws water from the cells, predominantly in the moderate freezing range down to about -20°C. As the process continues, ice crystals grow, cells shrink, and membranes and cell constituents are damaged. With further cooling, ice crystals may form within the cell, and disrupt organelles and cell membranes and cell death certainly occurs. Whether the ice is extracellular or intracellular, water is removed from the biologic system and desiccation results in cell death (Gage and Baust, 1998; Inoue et al., 2014; Beal and Fonseca, 2015). Considering the great importance of LAB in manufacturing various fermented food, the ability of the cells to be stabilized and preserved should be guaranteed. To prevent or reduce these adverse effects of freezing preservation, many substances have been used as cryoprotectants, such as skim milk, sodium ascorbate, and sugars, including trehalose, maltose, sucrose, glucose, and lactose (De Giulio et al., 2005; Jalali et al., 2012). However, apart from the use of cryoprotectants, the resistance of the cells to cold damage may effectively preserve cellular activities for a long time.

Adaptive laboratory evolution (ALE) has been used to obtain microorganisms that express the desired phenotypes (Dettman et al., 2012; Dragosits and Mattanovich, 2013). For example, piezotolerant or antibiotic resistant E. coli were successfully produced by ALE. In the both cases, concerted mutations occurred in the genes related to the evolved phenotype (Marietou et al., 2015; Jahn et al., 2017). ALEs of probiotics were performed for acid tolerance with Lactobacillus casei and Bificobacterium longum and they exhibited a significant increase of tolerance showing viability at lethal pH (Zhang et al., 2012; Jiang et al., 2016). While freeze-thaw (FT)-tolerant E. coli and industrial baker’s yeast were produced using the ALE method (Sleight and Lenski, 2007; Aguilera et al., 2010), studies have not reported the application of ALE for the production of FT-tolerant probiotics. In this study, the evolutionary adaptation method was used to obtain FT-tolerant L. rhamnosus GG by repeating 150 cycles of freeze-thaw-growth (FTG) for four replicates. The improvement in fitness was evaluated by comparing the extent of evolutionary adaptation of FTG-evolved mutants with that of their ancestor. In addition, genetic and phenotypic changes in FTG-evolved mutants were investigated.

Materials and Methods

Strain and Culture Conditions

Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG used in this study was obtained from the Korean Collection for Type Cultures (KCTC) with a strain number of KCTC 5033, where the strain have been sub-deposited from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) with strain number of ATCC 53103. L. rhamnosus GG (KCTC 5033) and its mutants were maintained in long-term storage at -70°C with glycerol (15% v/v) as a cryoprotectant. In FTG evolution experiment and assays for FT survival under FTG regime, glycerol was excluded to investigate the evolutionary changes in terms of survival and recovery. To ensure that cells were in physiologically comparable states at the start of FT survival and competitive fitness assays, cells were removed from the freezer, inoculated into MRS medium (Difco, Detroit, MI, United States) independently for each replicate assay, and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. The cultures were diluted 100-fold with fresh MRS broth and incubated at 37°C again for 24 h, followed by their use for all assays.

Evolutionary Adaptation to the FTG Regime

In order to provide higher level of stress to microbial cells, we compared the survival rates of L. rhamnosus GG after freezing at various temperatures for 6 h. As results, at deep-freezing temp (-80°C), the survival rate was relatively high (>70%) revealing lower level of freezing stress to microbial cells, possibly due to the formation of small size ice crystal (Gilkey and Staehelin, 1986). Thereby, we increased the temperature gradually and found that -30°C was proper to give high level of freezing stress (60% survival rate) as well as fast freezing (6 h). Meanwhile, -18°C resulted in the same level of freezing stress (60% survival rate) but slower freezing rate (>6 h). Evolutionary experiment was processed in 1 mL of MRS medium using Eppendorf tubes with four replicates from the original ancestor L. rhamnosus GG KCTC5033. It was performed with a regime of 1 day of freezing at -30°C for 6 h (without added cryoprotectant) and thawing at 13°C for 2 h, followed by growth in a fresh medium after 1% inoculation at 37°C for 16 h. After 1-day cycle of freezing-thawing-growing (FTG), the 2nd cycle was repeatedly carried out. These four populations evolved for 150 times of 1-day FTG cycles, where 1 day corresponds to one cycle. During the FTG cycles, examination of contamination was performed every month using 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis. After 70, 100, 130, and 150 FTG cycles, colonies were isolated on MRS agar medium, and their FT survival rates and growth dynamics were analyzed to select single colony representing evolved replicates.

Calculation of FT Survival

For the analysis of survival rates of evolved replicates and ancestor, viable cell density of each population was measured after FT treatment. After thawing the frozen cells, they were serially diluted and appropriate volume of the cells were spreaded on MRS agar medium. After incubation at 37°C for 48 h, the numbers of colonies were counted. FT survival rate (S) was calculated as follows:

where N1 is the viable cell density measured after thawing the frozen cells and N0 is its initial cell density before freezing. Relative FT survival was expressed as a ratio compared to the survival rate of ancestor.

Growth Dynamics

Separate growth curves were obtained based on optical density (OD) at 600 nm for the evolved cells and their ancestor L. rhamnosus GG after treatment of 150 FTG cylcles for 24 h using a microplate spectrophotometer (PowerWave HT, BioTek, United States) to compare their growth dynamics at 37°C. OD values were measured every hour during lag phase, every 2 h from exponential phase to early strationary phase, and at 24 h. Other growth curves of L. rhamnosus GG were obtained at a 10-min interval from the start of the culture to the middle of exponential phase to estimate durations of their lag phases before growth commencement as well as their doubling times during their growth phases. The duration of lag phase was calculated using the general method given by Sleight and Lenski (2007). OD values from growth curve experiments were standardized by dividing by the initial OD measured immediately after the FT cycle before dilution and log2 transformed in order to express changes as doublings. The transformed data were plotted and inspected to identify exponential growth, and linear regression was performed on the identified exponential-phase data. The doubling time was calculated as the inverse of the slope of regression. The “apparent” lag phase was estimated by extrapolating the exponential growth back in time until the regression intersected with the initial OD measurement.

Whole Genome Resequencing

The genomes of the two evolved (LR1 and LR2) and ancestor L. rhamnosus GG strains were sequenced after 150 FTG cylcles. The evolved mutants were selected by single colony isolation on MRS agar medium, followed by confirmation of improved fitness. For each strain, genomic DNA was extracted using the genomic DNA prep kit (SolGent, Korea) for library construction, and DNA purity was determined by recording the ratio of absorbance at 260/280 and 260/230 nm using the Epoch plate reader (BioTek Instrument Inc., Winooski, VT, United States). The genomic DNA libraries were conctructed using TruSeq DNA PCR-free kit (Illumina, CA, United States). The DNAs were randomly fragmented and repaired to blunt end with end repair enzyme included in the kit. After A-tailing, 5′ and 3′ adapters were ligated. The genomes were sequenced with a sequencer, HiSeq4000 (Macrogen Inc., Korea). After quality control and quality filtering process, sequence reads were mapped first using L. rhamnosus ATCC 53103 as the reference genome (GenBank accession number NC_013198.1) (Morita et al., 2009) and next L. rhamnosus KCTC 5033 (GenBank accession number: CP031290) for correction of natural mutations with BWA (ver.0.7.12) program to produce aligned reads. After mapping, duplicated reads were removed with Picard (ver. 1.119) and variant calling were performed using SAMTool (ver. 1.2). The results were analyzed by comparing the sequences in the NCBI1 and BioCyc2 databases.

Statistical Analysis

All experiments were conducted in triplicate, and the results were presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analysis for significant differences was performed using one-way ANOVA in Minitab.

Results

Evolutionary Adaptation to the FTG Regime

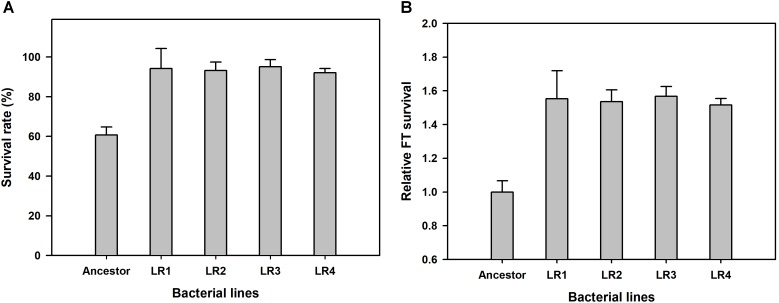

We performed ALE experiment under the FTG regime for 150 cycles, and compared the relative fitness of four FTG-evolved mutants and their ancestral strain. Survival rates were measured after FT treatment for 150 cycles, and they were calculated by measuring the viable cell density before and after FT treatment to show improved fitness under the FTG. As shown in Figure 1A, the mean survival rates of four evolved mutants were increased up to 93.65% after FT treatment from 60.69% (before FT treatment) showing great enhancement resulted from FTG evolution. As same, the overall fitness gains of four evolved mutants were 54% in terms of relative freeze-thaw survival compared to the ancestor strain (Figure 1B). Their increased fitness gains were all significant.

FIGURE 1.

Overall fitness gains after 150 cycles of freeze-thaw-growth (FTG) regime in terms of changes in survival rate (A) and freeze-thaw (FT) survival (B) of FTG-evolved mutants and their ancestral Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG strain. The four evolved mutants designated as LR1 to LR4 evolved for 150 FTG cycles. Error bars are standard deviation from three replicates. Values with different letters are significantly different (P < 0.05).

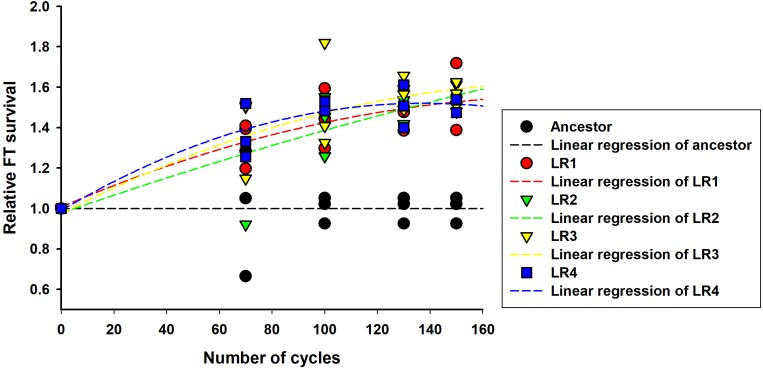

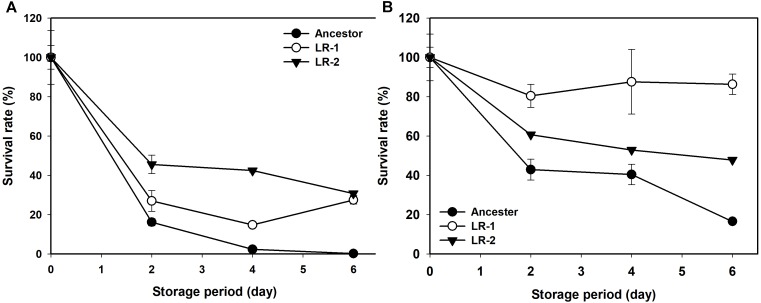

Next, the rates of evolution and FT survival improvement of evolved mutants were measured after 70, 100, 130, and 150 cycles of FTG treatment (Figure 2). The four evolved mutants showed a rapid increase in relative FT survival during the initial stage of FTG treatment, but the rates of increase were gradually slowed down after 100 cycles; particularly LR4 mutant exhibited a decrease in the relative FT survival rate, thereafter. As shown in Figure 3, during the frozen storage at -30°C for 6 days, the survival rates of 150 cycle-evolved mutants (LR 1 and LR 2) and ancestor were compared. When cells were frozen in MRS medium without trehalose as a cryoprotectant, the freezing stress at -30°C for 6 days was lethal to the ancestral strain showing 0.2% survival rate, while the evolved mutants, LR 1 and LR 2, were tolerant to the stress showing 27.4 and 30.7% of survival rates, respectively. When those cells were frozen with 0.3 M trehalose, the ancestor obtained low level of tolerance (16.5%) after 6 days, while LR-1 and LR-2 showed significant increase of tolerance, 86.3 and 47.8%, respectively. This result reveals that the evolved mutants after 150 cyles of FTG regime, obtained an improved fitness (survival rates) to the condition of frozen storage.

FIGURE 2.

Rates of evolution and FT survival improvement in FTG-evolved L. rhamnosus GG.

FIGURE 3.

Changes in survival rate of FTG-evolved mutants and their ancestral L. rhamnosus GG strain during frozen preservation at –30°C in MRS with no cryprotectant (A) and in MRS with 0.3 M trehalose as cryprotectant (B). The two evolved mutants designated as LR1 and LR2 are evolved for 150 FTG cycles. Error bars are standard deviation from three replicates.

Changes in Growth Dynamics

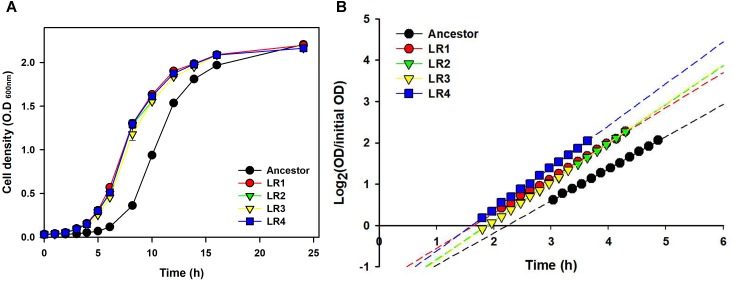

To compare growth dynamics of the evolved mutants and their ancestral strain after 150 cycles of FTG, two different types of growth curves were obtained (Figure 4). Figure 4A shows the growth dynamics, based on the OD, for four evolved mutants and their ancestor after FT treatment. Differences in the growth dynamics between these strains were apparent following the FT cycle. All evolved groups showed faster growth than their ancestor. Figure 4B shows the doubling time during the exponential growth phase and apparent lag duration calculated as described in the Section “Materials and Methods.” The evaluation of growth curves after FT treatment showed that the evolved mutants showed much faster exponential growth rates, with a 13-min shorter mean doubling time than their ancestor. The apparent lag phase of the ancestor was 134 min, while the mean apparent lag phase for the evolved mutants was only 105 min, indicating a difference of 29 min (Figure 4B).

FIGURE 4.

Growth dynamics (A) and lag phases (B) following FT treatment for four FTG-evolved mutants and their ancestor L. rhamnosus GG.

Genome Sequence of L. rhamnosus GG

In this study, we used L. rhamnosus GG obtained from the KCTC with a strain number of KCTC 5033, where the strain have been sub-deposited from the ATCC with strain number of ATCC 53103. We analyzed the whole genome sequence of L. rhamnosus GG KCTC 5033 and mapped using L. rhamnosus ATCC 53103 as the reference genome (GenBank accession number NC_013198.1). We found 41 SNPs in KCTC 5033 strain (Table 1). The sequences of L. rhamnosus GG KCTC 5033 were deposited in GenBank (accession numbers: CP031290).

Table 1.

Identification of SNPs in genome of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG KCTC 5033 compared with that of L. rhamnosus GG ATCC 53103 as the reference genome.

| No | Start | End | Strand | Mutation Position | Reference sequence | Altered sequence | Amino acid change | Enzyme |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 263021 | 264508 | ++ | 264278 | G | A | Ala→Thr | MFS transporter |

| 2 | 614219 | 616219 | + | 615483 | T | C | Leu→Pro | PTS beta-glucoside transporter subunit IIABC |

| 3 | 655200 | 657050 | - | 656560 | ACGCCGCC | ACGCCGCCGCC | QGGV→ QGGGV | alpha-glycerophosphate oxidase |

| 4 | Intergenic space | / | 751602 | G | A | / | / | |

| 5 | Intergenic space | / | 751632 | T | G | / | / | |

| 6 | Intergenic space | / | 751633 | T | C | / | / | |

| 7 | Intergenic space | / | 751663 | T | C | / | / | |

| 8 | 876317 | 876952 | - | 876397 | TGCCGCCG | TGCCGCCGCCG | LPGGI→ LPAGGI | Copper homeostasis protein CutC |

| 9 | Intergenic space | / | 1154682 | T | G | / | / | |

| 10 | 1370968 | 1372521 | + | 1372183 | T | A | Leu→Met | 2′, 3′-cyclic nucleotide 2′-phosphodiesterase |

| 11 | Intergenic space | / | 1873061 | CGG | CG | / | / | |

| 12 | Intergenic space | / | 1873072 | G | T | / | / | |

| 13 | Intergenic space | / | 1873075 | C | G | / | / | |

| 14 | Intergenic space | / | 1873076 | T | C | / | / | |

| 15 | Intergenic space | / | 1873089 | G | A | / | / | |

| 16 | Intergenic space | / | 1873091 | T | C | / | / | |

| 17 | Intergenic space | / | 1873092 | G | A | / | / | |

| 18 | Intergenic space | / | 1873879 | T | C | / | / | |

| 19 | Intergenic space | / | 1883242 | C | A | / | / | |

| 20 | 1993822 | 1997424 | - | 1994717 | T | A | Asp→Val | peptidoglycan-binding protein LysM |

| 21 | 2158636 | 2160858 | + | 2158707 | C | T | X | BREX-1 system adenine-specific DNA-methyltransferase |

| 22 | 2158636 | 2160858 | + | 2158710 | G | A | X | |

| 23 | 2158636 | 2160858 | + | 2158719 | C | T | X | |

| 24 | 2161973 | 2165527 | - | 2164868 | T | C | X | BREX-1 system adenine-specific DNA-methyltransferase |

| 25 | 2161973 | 2165527 | - | 2164871 | A | G | X | |

| 26 | 2351546 | 2355847 | - | 2352806 | G | A | X | Cell surface protein |

| 27 | 2351546 | 2355847 | - | 2352965 | A | T | X | |

| 28 | 2351546 | 2355847 | - | 2353053 | A | G | Val→Ala | |

| 29 | 2351546 | 2355847 | - | 2353148 | T | C | X | |

| 30 | 2351546 | 2355847 | - | 2353155 | T | C | Gln→Arg | |

| 31 | 2351546 | 2355847 | - | 2353178 | G | A | X | |

| 32 | 2351546 | 2355847 | - | 2353217 | A | G | X | |

| 33 | 2351546 | 2355847 | - | 2353220 | A | T | X | |

| 34 | 2351546 | 2355847 | - | 2353382 | G | A | X | |

| 35 | 2351546 | 2355847 | - | 2353391 | C | T | X | |

| 36 | 2351546 | 2355847 | - | 2353466 | G | A | X | |

| 37 | 2351546 | 2355847 | - | 2353548 | G | A | Ser→Phe | |

| 38 | 2351546 | 2355847 | - | 2353713 | A | G | Val→Ala | |

| 39 | 2452189 | 2453244 | + | 2452317 | A | G | X | Hypothetical protein |

| 40 | 2574214 | 2574357 | + | 2574344 | A | G | Glu→Gly | Malolactic regulator |

| 41 | 2574214 | 2574357 | + | 2574345 | A | G | X | |

Analyses of Genetic Changes

To compare the genetic changes in the evolved mutants, genome sequences of the two FTG-evolved mutants (LR1 and LR2) were analyzed and compared with that of L. rhamnosus KCTC 5033. As presented in Table 2, the mutations in the FTG-evolved mutants were identified both in six gene regions and an intergenic space. Single-nucleotide polymoprphism (SNP) mutations in the cardiolipin synthase gene were detected in both LR1 and LR2 mutants at different gene loci. The gene encoding exopolysaccharide biosynthesis protein showed sequence variations at two different positions within the same gene region. BREX-1 system adenine-specific DNA-methyltransferase gene was mutated at two gene regions that encoded the same protein. The gene encoding 2-nitropropane dioxygenase also showed the same mutation at the same position in both mutant strains. The mutations in the genes encoding D-alanyl-D-alanine carboxypeptidase and N-acetylmuramic acid-6-phosphate etherase were found only in the LR2 mutant. The mutation in the intergenic space was located between LGG_RS07350 gene, encoding a terminase, and LGG_RS07355 gene, encoding a recombinase.

Table 2.

Genetic mutations identified in FTG-evolved L. rhamnosus GG clones.

| Position (bp) | Gene or region | Gene description | Mutation | Identification of mutation |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LR 1 | LR 2 | ||||

| 256855 | LGG_RS01240 (dacA) | D-Alanyl-D-alanine carboxypeptidase | Insertion (position 903, +A) | × | ○ |

| 1272968 | LGG_RS06120 (cls) | Cardiolipin synthase | Missense | ○ | × |

| 1473969 | LGG_RS07040 (cls) | × | ○ | ||

| 2106059 | LGG_RS09880 (wze) | Exopolysaccharide biosynthesis protein | Missense | × | ○ |

| 2106381 | ○ | × | |||

| 2160010 | LGG_RS10085 (pglX) | BREX-1 system adenine-specific DNA-methyltransferase | Missense | ○ | ○ |

| 2163622 | LGG_RS10095 (pglX) | ○ | ○ | ||

| 2192576 | LGG_RS10195 (fabK) | 2-nitropropane dioxygenase | Missense | ○ | ○ |

| 2844194 | LGG_RS13275 (murQ) | N-acetylmuramic acid-6-phosphate etherase | Missense | × | ○ |

| 1551606 | LGG_RS07350← / ←LGG_RS07355 | Intergenic space | Intergenic mutation (-117/+365, G to T) | ○ | ○ |

Discussion

Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (ATCC 53103) is one of the most studied probiotic strains that has shown to give beneficial effects to host. Probiotic foods should be safe and contain appropriate probiotic organisms in sufficient number at the time of consumption. Therefore, the probiotic strain selected must be suitable for large-scale industrial production and should be able to survive and retain its functionality during production and storage as frozen or dried culture (Tripathi and Giri, 2014). Freezing has been generally used to preserve starter cultures for years because it effectively inhibits the activities of spoilage microorganisms and maintains the starter cultures for a long time (Archer, 2004; Barria et al., 2013). However, ice crystal formation may occur in the extracellular spaces during freezing and cause cell destruction. Thus, development of FT-tolerant probiotic microorganisms is desirable for their safe and effective applications in food industries.

We produced four evolved mutants that showed FT tolerance. All mutant strains exhibited enhanced fitness including improved survival rates, faster growth rate, and shortened lag phase and doubling time than those of the ancestor (Figures 1–4). This result is comparable with those of previous reports, wherein the evolutionarily adapted strains of E. coli and industrial baker’s yeast subjected to FT stress showed improved fitness after ALE using the FTG regime or growth at low temperature (Sleight and Lenski, 2007; Aguilera et al., 2010). The FT survival representing evolution rates increased rapidly at the initial FTG treatment, but slowed down after 100 cycles. The same trend was observed in other microorganisms such as in E. coli and yeast; previous studies have reported the rapid increase in fitness observed during the early phase that eventually slows down during the extended evolution in ALE experiments (Sleight and Lenski, 2007; Aguilera et al., 2010). This phenomenon also accompanies accumulation of random mutagenesis along with the evolutionary cycles that would result in network complexity to lose intrinsic microbial attributes (Hua et al., 2007; Barrick et al., 2009).

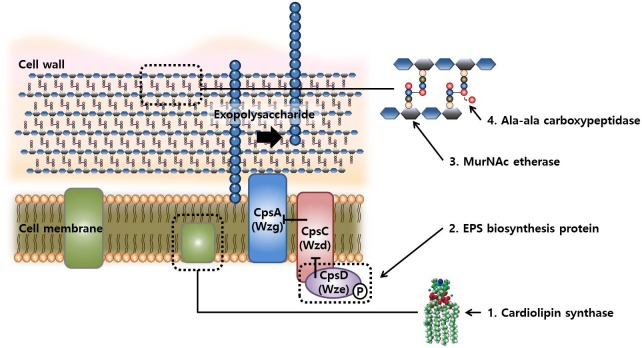

Genetic changes of L. rhamnosus GG during the ALE procedure were determined through the comparison of the genome sequences of FTG-evolved strains and their ancestor. In this procedure, we identified 41 SNPs in the genome of KCTC 5033 ancestor strain compared with the genome of ATCC 53103 strain (Table 1). Those single mutations are supposed to have been occurred randomly during the preservation period in the KCTC after sub-deposition from the ATCC. This result reveals that most genome sequences of stock cultures harbored in culture collection centers or laboratories might be changed by random mutagenesis along with preservation period. Mutations in the evolve mutants were identified in six genes and in one intergenic space (Table 2). Most mutated genes were involved in the biosynthesis of the cell wall or membrane (Hirschberg and Kennedy, 1972; Shibuya and Hiraoka, 1992; Jaeger and Mayer, 2008; Mohammadi et al., 2011; Liechti et al., 2014; Kang et al., 2015). In addition, the mutation in the intergenic space may affect the regulatory sequence of the gene region. The mutations in the evolved lines may disrupt the function of the encoded enzymes and consequently cause structural changes in cell membranes and walls, resulting in an increase in the cellular fluidity that is known to benefit cells by providing resistance against FT stress. In biology, membrane fluidity refers to the viscosity of the lipid bilayer of a cell membrane or a synthetic lipid membrane (Gennis, 1989).

The genes encoding D-alanyl-D-alanine carboxypeptidase (DacA) and N-acetylmuramic acid-6-phosphate etherase (MurQ) are involved in peptidoglycan (PG) synthesis. PG is the major component of the gram-positive bacterial cell wall and ensures cell wall rigidity and stability. PG is a macromolecule comprising glycan chains made up of alternating β-1,4-linked N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) and N-acetylmuramic acid (MurNAc) cross-linked with oligopeptides at the lactic acid residue of MurNAc. During PG biosynthesis, a dipeptide ligated with two D-alanine by D-alanine-D-alanine ligase is first added to the tripeptide in PG stem by MurF resulting in a pentapeptide. Thereafter, the terminal D-alanine is cleaved from the stem peptide catalyzed by DacA (EC 3.4.16.4) and the resulting tetrapeptide is cross-linked with adjacent peptide stems by transpeptidases (penicillin binding proteins) (Liechti et al., 2014). Furthermore, MurQ (EC 4.2.1.126, MurNAc-6-P etherase) is known to catalyze the cleavage of MurNAc 6-phosphate, with GlcNAc 6-phosphate and d-lactate involving in the recycle of PG (Jaeger et al., 2005; Jaeger and Mayer, 2008). While no experimental evidence of the reverse reaction by this enzyme to synthesize MurNAc 6-phosphate connecting PG between glycan and peptide, MurQ is supposed to be one of the core enzyme for PG metabolism. Mutations at dacA and murQ genes in LR1 and LR2 may cause changes (possibly decrease) in the enzymatic activity and affect the crosslinking between peptide chains and alteration in the synthesis (or recycle) of PG, consequently leading to a decrease in cell wall rigidity.

Cardiolipin (CL) synthase (encoded by cls gene) is involved in the synthesis of the cellular compartment of lipid bilayer. It converts two phosphatidylglycerol molecules into CL and glycerol in the membrane during stationary phase (Hirschberg and Kennedy, 1972; Shibuya and Hiraoka, 1992). CL is a dominant phospholipid in stationary-phase cells and functional defects in cls gene can inhibit CL synthesis and PG accumulation during stationary phase (Bauman et al., 1965; Houtsmuller and Van Deenan, 1965; Pluschke et al., 1978; Pluschke and Overath, 1981). Previous studies reported that cls E. coli mutant altered membrane phase transitions during or after temperature downshift, resulting in a significant increase in the membrane fluidity, while other cls- mutants represented improved FT survival and growth rate after FT treatment (Pluschke and Overath, 1981; Sleight et al., 2008). As same, in our study, it was found that the cls gene may be involved in the membrane structure of L. rhamnosus GG.

The protein Wze or CpsD is involved in the biosynthesis of exopolysaccharide (EPS) or capsular polysaccharides (CPS) in bacteria, respectively. A phosphorylation complex containing Wze (CpsD homolog), an autophosphorylating tyrosine kinase, and Wzb (CpsB), a phosphotyrosine protein phosphatase, is thought to be involved in the regulation of EPS biosynthesis (Lebeer et al., 2009). This mechanism was proved by Toniolo et al. (2015) by performing a mutational study for each gene associated with the biosynthesis of CPS in Streptococcus agalactiae. CpsA was found responsible for the transfer of CPS from the membrane lipid to cell wall peptidoglycan, and this process was controlled by CpsC that inhibits the action of CpsA. CpsC is inhibited by the activation of CpsD, resulting in CpsA activation and CPS transfer. The loss-of-function mutation in wze (CpsD) fails to inhibit CpsC and this change results in the continuous elongation of CPS on the membrane.

Taken together, the mutations in the evolved strains after FT treatment mainly occurred in the genes related to the biosynthesis of cell membrane, cell wall, and capsular polysaccharides. The hypothetical mechanisms underlying these mutations are illustrated in Figure 5. The cell envelope is rigid and highly structured to maintain the cell structures and protects cells from environmental stress. However, functional defects in these genes may produce incomplete cell wall or membrane, resulting in a flexible cell envelope that may be beneficial in FT stress because these cells are more tolerant to the pressure of ice crystal formation in intra- and extracellular space as compared with the wild-type cells.

FIGURE 5.

Schematic representation of the compartment synthesis in cellular structures and possible synthetic reactions involved in changes in FT-tolerance by mutations.

Additional mutations were identified in two genes and in one intergenic space. One of the mutated genes was that encoding 2-nitropropane dioxygenase (FabK), an enzyme catalyzes the oxidation of nitroalkanes into their corresponding carbonyl compounds and nitrite, and the other gene encoded BREX-1 system adenine-specific DNA-methyltransferase (pglX), which can be involved in the phage resistance system. The genes adjacent to the mutation point of intergenic space were those encoding the phage terminase small subunit P27 family and recombinase family protein. Phage terminase small subunit P27 family is an enzyme that creates cohesive ends during DNA packaging, while the recombinase family protein catalyzes DNA recombination for the manipulation of genome structure and control of gene expression. However, a possible association between these genes and FT stress is not clear yet.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we were able to select the FT-tolerant L. rhamnosus GG mutants (4 lines) by ALE repeating a day-FTG regime. After FT treatment for 150 cycles, the survival rates of mutants were significantly improved: reaching up to >90% from 60%. Genome sequencing of two mutants showed six SNP mutations occurred in their chromosome and they were related to the biosynthetic mechanisms of cellular membrane-wall-EPS structure. Incomplete or altered formation of cellular envelope might result in enhancement in its flexibility, which plays important roles in the microbial FT tolerance. In this study, we report, for the first time, the effect of mutations in dacA and murQ genes related with freeze-thaw tolerance of cells. This study demonstrates a feasibility of ALE to select microorganisms possessing preferred phenotypes caused by genetic changes in multiple genes located distant loci of chromosomal DNA.

Author Contributions

NH conceived and supervised this study. YK performed the experiments and generated the draft manuscript. All authors contributed to data interpretation. J-HB and S-AK contributed organizing data, statistical analysis, gene annotation, and writing the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding. This work was supported by Korea Institute of Planning and Evaluation for Technology in Food, Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (IPET) through Agricultural Microbiome R&D Program, funded by Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (MAFRA) (918006-04-1SB010) and by Traditional Culture Convergence Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning (NRF-2017M3C1B5019292).

References

- Aguilera J., Andreu P., Randez-Gil F., Prieto A. J. (2010). Adaptive evolution of baker’s yeast in a dough-like environment enhances freeze and salinity tolerance. Microb. Biotechnol. 3 210–221. 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2009.00136.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer D. L. (2004). Freezing: an underutilized food safety technology? Int. J. Food Microbiol. 90 127–138. 10.1016/S0168-1605(03)00215-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banna G. L., Torino F., Marletta F., Santagati M., Salemi R., Cannarozzo E., et al. (2017). Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG: an overview to explore the rationale of its use in cancer. Front. Pharmacol. 8:603. 10.3389/fphar.2017.00603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barria C., Malecki M., Arraiano C. M. (2013). Bacterial adaptation to cold. Microbiology 159 2437–2443. 10.1099/mic.0.052209-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrick J. E., Yu D. S., Yoon S. H., Jeong H., Oh T. K., Schneider D., et al. (2009). Genome evolution and adaptation in a long-term experiment with Escherichia coli. Nature 461 1243–1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauman N. A., Hagan P. Q., Goldfine H. (1965). Phospholipids of Clostridium butyricum, studies on plasmalogen composition and biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 240 1559–1567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beal C., Fonseca F. (2015). “Freezing of probiotic bacteria,” in Advances in Probiotic Technology, eds Foerst P., Santivarangkna C. (Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; ), 179–212. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho A. S., Silva J., Ho P., Teixeira P., Malcata F. X., Gibbs P. (2004). Relevant factors for the preparation of freeze-dried lactic acid bacteria. Int. Dairy J. 14 835–847. 10.1016/j.idairyj.2004.02.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Giulio B., Orlando P., Barba G., Coppola R., De Rosa M., Sada A., et al. (2005). Use of alginate and cryo-protective sugars to improve the viability of lactic acid bacteria after freezing and freeze-drying. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 21 739–746. 10.1007/s11274-004-4735-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dettman J. R., Rodrigue N., Melnyk A. H., Wong A., Bailey S. F., Kassen R. (2012). Evolutionary insight from whole-genome sequencing of experimentally evolved microbes. Mol. Ecol. 21 2058–2077. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05484.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragosits M., Mattanovich D. (2013). Adaptive laboratory evolution – principles and applications for biotechnology. Microb. Cell Fact. 12:64. 10.1186/1475-2859-12-64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gage A. A., Baust J. (1998). Mechnisms of tissue injury in cryosurgery. Cryobiology 37 171–186. 10.1006/cryo.1998.2115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gennis R. B. (1989). “The structures and properties of membrane lipids,” in Biomembranes, ed. Gennis R. B. (New York, NY: Springer-Verlag New York; ), 36–84. [Google Scholar]

- Gilkey J. C., Staehelin L. A. (1986). Advances in ultrarapid freezing for the preservation of cellular ultrastructure. Microsc. Res. Tech. 3 177–210. 10.1002/jemt.1060030206 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin B. R., Gorbach S. L., Saxelin M., Barakat S., Gualtieri L., Salminen S. (1992). Survival of Lactobacillus species (strain GG) in human gastrointestinal tract. Dig. Dis. Sci. 37 121–128. 10.1007/BF01308354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill C., Guarner F., Reid G., Gibson R. G., Merenstein J. D., Pot B., et al. (2014). The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 11 506–514. 10.1038/nrgastro.2014.66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschberg C. B., Kennedy E. P. (1972). Mechanism of the enzymatic synthesis of cardiolipin in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 69 648–651. 10.1073/pnas.69.3.648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houtsmuller U., Van Deenan L. (1965). On the amino acid esters of phosphatidyl glycerol from bacteria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 106 564–576. 10.1016/0005-2760(65)90072-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua Q., Joyce A. R., Palsson B. Ø., Fong S. S. (2007). Metabolic characterization of Escherichia coli strains adapted to growth on lactate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73 4639–4647. 10.1128/AEM.00527-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue M., Nakatsuka S., Jinzaki M. (2014). Cryoablation of early-stage primary lung cancer. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014:521691. 10.1155/2014/521691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger T., Arsic M., Mayer C. (2005). Scission of thelactyl ether bond of N-acetylmuramic acid by Escherichia coli “Etherase”. J. Biol. Chem. 280 30100–30106. 10.1074/jbc.M502208200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger T., Mayer C. (2008). N-acetylmuramic acid 6-phosphate lyases (MurNAc etherases): role in cell wall metabolism, distribution, structure, and mechanism. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 65 928–939. 10.1007/s00018-007-7399-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahn L. J., Munck C., Ellabaan M. M. H., Sommer M. O. A. (2017). Adaptive laboratory evolution of antibiotic resistance using different selection regimes lead to similar phenotypes and genotypes. Front. Microbiol. 8:816. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jalali M., Abedi D., Varshosaz J., Najjarzadeh M., Mirlohi M., Tavakoli N. (2012). Stability evaluation of freeze-dried Lactobacillus paracasei subsp. tolerance and Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus in oral capsules. Res. Pharm. Sci. 7 31–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Ren F., Liu S., Zhao L., Guo H., Hou C. (2016). Enhanced acid tolerance in Bifidobacterium longum by adaptive evolution: comparison of the genes between the acid-resistant variant and wild-type strain. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 26 452–460. 10.4014/jmb.1508.08030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Henry K. C., Donato K. A., Shen-Tu G., Gordanpour M., Sherman P. M. (2008). Lactobacillus rhamnosus strain GG prevents enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7-induced changes in epithelial barrier function. Infect. Immun. 76 1340–1348. 10.1128/IAI.00778-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang H. J., Gilbert C., Badeaux F., Atlan D., LaPointe G. (2015). A tyrosine phosphorylation switch controls the interaction between the transmembrane modulator protein Wzd and the tyrosine kinase Wze of Lactobacillus rhamnosus. BMC Microbiol. 15:40. 10.1186/s12866-015-0371-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebeer S., Verhoeven T. L. A., Francius G., Schoofs G., Lambrichts I., Dufrene Y., et al. (2009). Identification of a gene cluster for the biosynthesis of a long, galactose-rich exopolysaccharide in Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and functional analysis of the priming glycosyltransferase. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75 3554–3563. 10.1128/AEM.02919-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liechti G. W., Kuru E., Hall E., Kalinda A., Brun Y. V., VanNieuvenhze M., et al. (2014). A new metabolic cell-wall labelling method reveals peptidoglycan in Chlamydia trachomatis. Nature 506 507–510. 10.1038/nature12892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marietou A., Nguyen A. T. T., Allen E. E., Bartlett D. H. (2015). Adaptive laboratory evolution of Escherichia coli K-12 MG1655 for growth at high hydrostatic pressure. Front. Microbiol. 5:749. 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi T., Dam V., Sijbrandi R., Vernet T., Zapun A., Bouhss A., et al. (2011). Identification of FtsW as a transporter of lipid-linked cell wall precursors across the membrane. EMBO J. 30 1425–1432. 10.1038/emboj.2011.61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita H., Toh H., Oshima K., Murakami M., Taylor T. D., Igimi S., et al. (2009). Complete genome sequence of the probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus ATCC 53103. J. Bacteriol. 191 7630–7631. 10.1128/JB.01287-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluschke G., Hirota Y., Overath P. (1978). Function of phospholipids in Escherichia coli. Characterization of a mutant deficient in cardiolipin synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 253 5048–5055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluschke G., Overath P. (1981). Function of phospholipids in Escherichia coli. Influence of changes in polar head group composition on the lipid phase transition and characterization of a mutant containing only saturated phospholipid acyl chains. J. Biol. Chem. 256 3207–3212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rault A., Béal C., Ghorbal S., Ogier J. C., Bouix M. (2007). Multiparametric flow cytometry allows rapid assessment and comparison of lactic acid bacteria viability after freezing and during frozen storage. Cryobiology 55 35–43. 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2007.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segers M. E., Lebeer S. (2014). Towards a better understanding of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG-host interactions. Microb. Cell Fact. 13:S7. 10.1186/1475-2859-13-S1-S7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibuya I., Hiraoka S. (1992). Cardiolipin synthase from Escherichia coli. Methods Enzymol. 209 321–330. 10.1016/S0005-2760(97)00100-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleight S. C., Lenski R. E. (2007). Evolutionary adaptation to freeze-thaw-growth cycles in Escherichia coli. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 80 370–385. 10.1086/518013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleight S. C., Orlic C., Schneider D., Lenski R. E. (2008). Genetic basis of evolutionary adaptation by Escherichia coli to stressful cycles of freezing, thawing and growth. Genetics 180 431–443. 10.1534/genetics.108.091330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toniolo C., Balducci E., Romano M. R., Proietti D., Ferlenghi I., Grandi G., et al. (2015). Streptococcus agalactiae capsule polymer length and attachment is determined by the proteins CpsABCD. J. Biol. Chem. 290 9521–9532. 10.1074/jbc.M114.631499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi M. K., Giri S. K. (2014). Probiotic functional foods: survival of probiotics during processing and storage. J. Funct. Foods 9 225–241. 10.1016/j.jff.2014.04.030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Wu C., Du G., Chen J. (2012). Enhanced acid tolerance in Lactobacillus casei by adaptive evolution and compared stress response during acid stress. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 17 283–289. 10.1007/s12257-011-0346-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Zhu Y. H., Yang G. Y., Liu X., Xia B., Hu X., et al. (2018). Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG affects microbiota and suppresses autophagy in the intestines of pigs challenged with Salmonella Infantis. Front. Microbiol. 8:2705. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]