Abstract

Background

The Simplified Psoriasis Index is a tool that assesses the current severity, psychosocial impact, past history and interventions in patients with psoriasis through separate components. Two versions are available, one in which the current severity of the disease is evaluated by the patient themselves and another by the physician.

Objectives

Translate the Simplified Psoriasis Index into Brazilian Portuguese and verify its validity.

Methods

The study was conducted in two stages; the first stage was the translation of the instrument; the second stage was the instrument's validation.

Results

We evaluated 62 patients from Complexo Hospitalar Santa Casa de Porto Alegre and Hospital Universitário de Brasília. The Simplified Psoriasis Index translated into Portuguese showed high internal consistency (Cronbach test 0.68).

Study limitations

Some individuals, because of poor education, might not understand some questions of the Simplified Psoriasis Index.

Conclusions

The Brazilian Portuguese version of the Simplified Psoriasis Index was validated for our population and can be recommended as a reliable instrument to assess the patients with psoriasis.

Keywords: Indicators of quality of life, Psoriasis, Quality of life

INTRODUCTION

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory systemic condition that affects the skin and joints. It is associated to physical and psychological morbidity of patients.1 The evaluation of its extent and severity is based in the evaluation of signs and symptoms of the disease. The most used index for this purpose is the PASI (Psoriasis Area and Severity Index), which estimates the body surface area as well as the clinical presentation of psoriasis through a physical examination performed by the dermatologist.1 However, this tool not always reflects the impact of the disease in the life of patients.2,3 In order to complement the evaluation of these patients, the DLQI (Dermatology Life Quality Index), frequently used in the evaluation of dermatologic disease, can also be used.4,5 This index aids in cases where there is marked improvement in the extent of the disease and little changes in the quality of life after treatment because the patient remains with lesions on visible areas such as the hands.1

The accurate identification of disease severity is crucial for the adequate choice of the available therapies and follow-up of therapeutic responses.1 A new was of assessing patients with psoriasis is the Simplified Psoriasis Index (SPI), which encompasses physical and psychosocial involvement, past history and interventions that make the follow-up more thorough. The index was developed in the United Kingdom and has already been validated for the English language. It is easy to use and can help better identifying the severity and in the management of patients.6,7

The objective of our study is to translate into Brazilian Portuguese and validate the Simplified Psoriasis Index in our population.

METHODS

Original questionnaires already validated in the English language were sent by the author who also authorized its use for validation in Brazilian Portuguese (Chart 1). A prospective study through interviews was performed, with data collected between July and September 2015 in the outpatient clinic of psoriasis of the Complexo Hospitalar Santa Casa de Porto Alegre and Hospital Universitário de Brasília. All patients signed a consent form. Pediatric patients, illiterates and/or unable to fill out the form by themselves were excluded from the study. Calculation of the sample was not performed, and consecutive patients seen at the outpatient clinic of psoriasis were included.

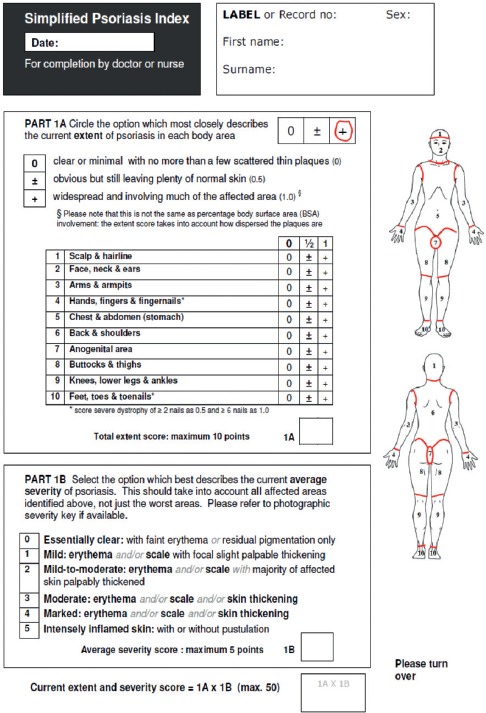

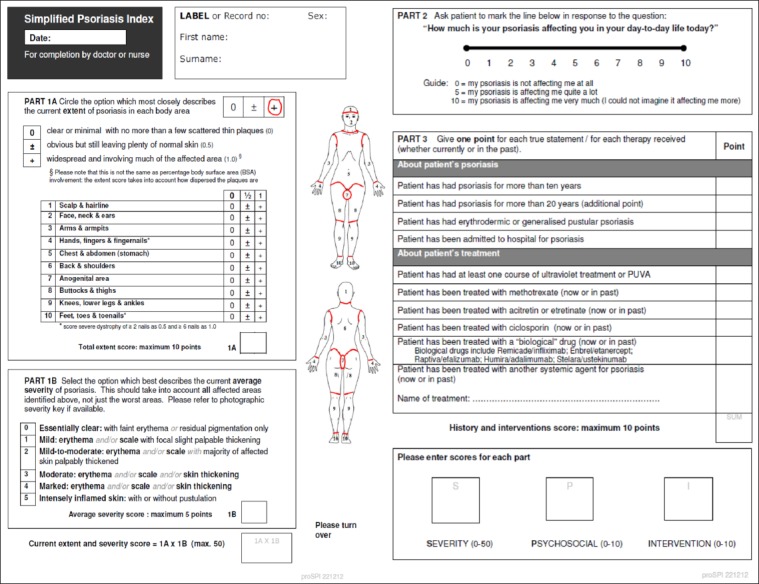

Chart 1.

Original version of the Simplified psoriasis index, completed by physician and patient

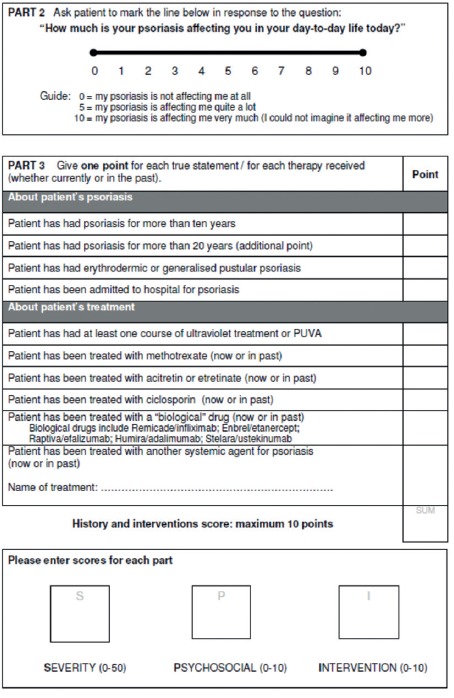

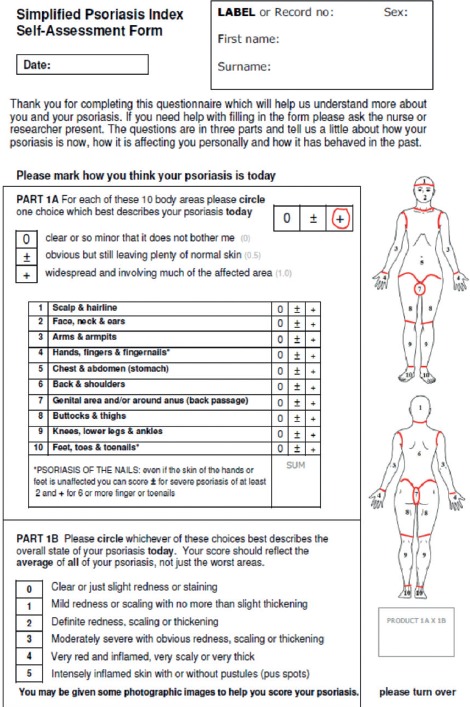

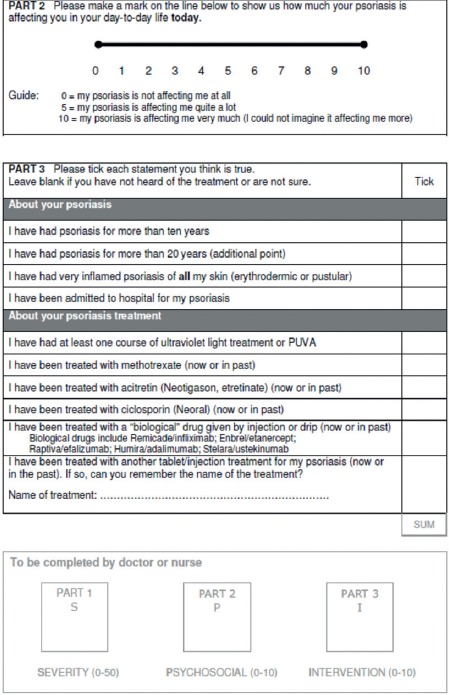

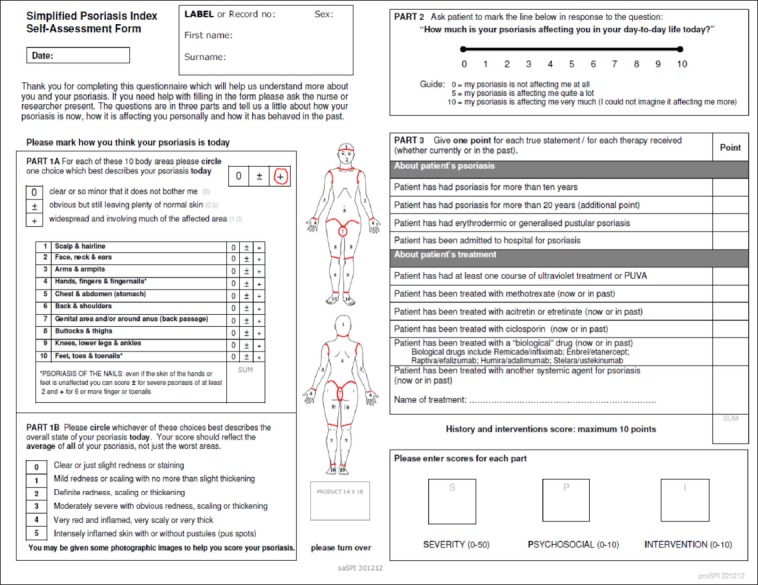

The questionnaire used was the Simplified Psoriasis Index. The instrument was translated into Brazilian Portuguese and then back to English (translation/back translation). The final document translated into English from Portuguese was sent to the author, who evaluated the results.

The questionnaire has two versions: one completed by the physician (proSPI) and the other by the patient (saSPI) (Charts 2 and 3). Both differ only by the language, which is simplified for the patients. The SPI is divided into three components: the first corresponds to the current severity of the disease; the second evaluates the psychosocial impact of the disease; and the third shows the past history and interventions performed. Besides the questionnaire, the patients were submitted to general physical examination and dermatologic evaluation. Statistical analysis was performed using Bartlett's sphericity test, verifying if the analysis was adequate. Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test was performed to evaluate the consistency of the sample. Internal validation was analyzed with Cronbach's alpha, and the correlation between PASI and proSPi and saSPI, with Spearman's coefficient.

Chart 2.

Questionnaire completed by the physician (proSPI)

|

Chart 3.

Questionnaire completed by the patient (saSPI)

|

Our study's limitation was due to the poor education of some patients who had difficulties filling out the questionnaire.

RESULTS

the sample included 62, 31 males (50%) and 31 females (50%). Age ranged from 42 to 59 years and PASI median was 4.3, with minimum score of 2.3 and maximum of 7.2. According to the PASI, the majority of patients were classified as mild psoriasis (67.74%), followed by severe psoriasis (17.74%) and moderate psoriasis (14.51%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Median of the characteristics studied in psoriasis patients

| Characteristics/Subsets | Median | Interquartile interval |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 51 | 42-59 |

| PASI | 4,3 | 2.3-7.2 |

| saSPI subset 1 | 5 | 3-10 |

| saSPI subset 2 | 5 | 1-8 |

| saSPI subset 3 | 3 | 2-5 |

| proSPI subset 1 | 4 | 1.5-8 |

| proSPI subset 2 | 5 | 2-7 |

| proSPI subset 3 | 3.5 | 2-5 |

The validation of the instrument's construct was performed based on factorial analysis of the questions. For such, Bartlett's sphericity test was performed, which was statistically significant (p<0.001), indicating the variables are interrelated (the factorial analysis is adequate). The results for the validation test of the construct, known as Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test, are shown in Table 2. KMO helps to verify consistency in the sample. If the value of KMO is inferior to 0.60, we can say the consistency did not occur.

Table 2.

Values of Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test

| Subsets | KMO |

|---|---|

| saSPI: physical aspect of the lesions | 0.75 |

| saSPI: psychosocial influence | 0.68 |

| saSPI: previous and current treatments | 0.54 |

| proSPI: physical aspect of the lesions | 0.69 |

| proSPI: psychosocial influence | 0.69 |

| proSPI: previous and current treatments | 0.57 |

| Total | 0.65 |

The result of the validation of internal consistency was performed with the statistics of Cronbach's alpha. The expected value of Cronbach's coefficient should be superior to 0.7. However, since they are scales with less than 10 items (in this case, six), values above 0.5 can be accepted. The results are shown for each subset and the total in Table 3.

Table 3.

Validation of the internal consistency with Cronbach's alpha analysis

| Subset | Alpha |

|---|---|

| saSPI: physical aspect of the lesions | 0.49 |

| saSPI: psychosocial influence | 0.58 |

| saSPI: previous and current treatments | 0.73 |

| proSPI: physical aspect of the lesions | 0.54 |

| proSPI: psychosocial influence | 0.58 |

| proSPI: previous and current treatments | 0.73 |

| Total | 0.68 |

The correlation between SPI and PASI was performed with Spearman's rho (r), because it evaluates two ordinal and parametric variables. The test evaluates if there is a correlation, but not causality, and the results are between 0 and 1, being 1 a perfect linear correlation. The correlation coefficient between the patient's total SPI and the PASI was 0.66 (p<0.001), while the correlation coefficient between the physician's total SPI and the PASI was 0.79 (p<0.001), and the correlation coefficient between saSPI and proSPI, 0.83 (p<0.001). Measurements of the degree of correlation exist but, they are arbitrary and should be evaluated in the context and with caution. One of the most used categorizations of the degree of correlation determines that r above 0.90 is excellent; between 0.75 and 0.90 is good; between 0.50 and 0.74 is moderate; and below 0.50 is weak.

Properties of the test were explored, including sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values and accuracy. The sensitivity was defined as the proportion of individuals who the instrument classified as severe/moderate (true-positive) among those who were really that severe according to the gold-standard. Specificity was defined as the proportion of those classified by the test as mild (true-negative) among all those classified as mild according to the gold-standard. The positive predictive value was calculated as the proportion of positive tests as severe/moderate among the total of positive tests. The negative predictive value was calculated as the proportion of tests with negative results (mild) among the total of negative tests. The accuracy is the ability of the test in classifying correctly and was calculated as the sum of true-positives plus true-negatives divided by the total amount of tests. When the patients were stratified into two severity categories, mild and moderate/severe, proSPI sensitivity in relation to PASI was 33.3% whereas the specificity was 100%. The same values for saSPI were 33.3% and 85.7% for sensitivity and specificity, respectively (Table 4).

Table 4.

Characteristics of Simplified Psoriasis Index

| proSPI | saSPI | |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 100% | 85.7% |

| Specificity | 33.3% | 33.3% |

| Positive predictive value | 41.2% | 15.0% |

| Negative predictive value | 41.5% | 94.4% |

| Accuracy | 41.4% | 39.6% |

Cohen's Kappa coefficient was used to evaluate concordance between the tests in the three original categories (mild, moderate and severe), and the values of 0.42 (p=1) and 0.40 (p=1.0) were found for proSPI and saSPI, respectively.

DISCUSSION

The use of PASI as the evaluation method of psoriasis severity, although promoted through randomized clinical trials,2 does not accurately reproduce the extent and severity of the lesions, nor does it take into consideration the impact of the disease on the patient's quality of life.3 Patients with severe psoriasis can be well represented by the PASI when erythema, desquamation and induration are evaluated. However, individuals with mild psoriasis tend to be under-represented by the PASI, either in the severity assessment or in the assessment of the improvement of the lesions after treatment. Another clinical picture not well assessed by the PASI are patients with palmar and plantar, nail, genital and facial involvement, areas that, when affected, bring about enormous physical and psychological impact.

In the same fashion, indexes that only evaluate the impact of the disease in the quality of life can be of little help with the objective perception of improvement of the lesions, since patients with psoriasis have different perceptions of the disease. In other words, in the case of DLQI, two patients with the same type and severity of psoriasis can have very different indexes.

SPI is a holistic index that integrates the patient's and the physician's view. SPI evaluates the extent and severity of the disease as PASI does, and the psychosocial impact of the disease in a simpler way than DLQI, evaluating the extent, severity and impact of the disease and previous treatments. Some indexes as SPI have been proposed over the past few years and the indexes that evaluate the perspective of the patient in regard to their condition have been taken more into consideration6 (patient related outcome), but few have been put into practice in specialized outpatient clinics. During the validation process for the English language7, using Spearman's correlation, the authors found a correlation coefficient (r) between PASI and proSPI of 0.91, and of 0.70 between PASI and saSPI, whereas in the validation for the Portuguese language the values of 0.80 and 0.64 were found for proSPI and saSPI, respectively. The values of saSPI between the instrument in English and Brazilian Portuguese are classified as moderate correlation, whereas the values of proSPI between both instruments were close but categorized differently (good correlation of the instrument in Brazilian Portuguese, excellent correlation of the instrument in English). In any case, the correlation between PASI and both SPIs was positive for the Brazilian Portuguese version of the instrument.

We also observed with the study the little concordance as measured by Kappa between PASI, saSPI and proSPI when the category severity was analyzed. In this case, we reaffirm the main goal of this new tool: to better evaluate the impact of the disease and treatments. Patients with many lesions can present with less psychosocial impairment than others with lesions on the hands or genitals. Regarding the internal consistency of the construct, Bartlett's sphericity test was statistically significant (p<0.001) and KMO index demonstrated that, being superior to 0.60, there was intercorrelation between the variables in the instrument in Brazilian Portuguese. Total Cronbach's alpha, that also evaluates the internal consistency of the instrument, was 0.68, with a cut-off for good internal consistency above 0.50 in scales with less than 10 items, such as the case in question. Kappa's concordance index between proSPI or saSPI with PASI (gold-standard), using categorization of the patients as mild, moderate and severe (according to PASI), was 0.40 and 0.41 for saSPI and proSPI, respectively, with p=1. This demonstrates little concordance between PASI and both SPIs by using this categorization, what to a certain degree was expected, since SPI is a patient/physician integrated index and gives more importance to specific areas, while PASI is an objective index that evaluates the extent of the disease with no specific important areas. Thus, patients with genital, nail or face psoriasis, that can be classified as severe with SPI, would be classified as mild with PASI.

CONCLUSION

Integrated indexes such as SPI, made by a component professional/physician and a patient component, can provide a better assessment of the severity of psoriasis. The ability of evaluating the psychological impact of psoriasis and of giving more importance to specific body regions such as genitals, nails and face, makes SPI a more thorough index than PASI. The results seen with this validation are similar to the results seen by Chularojanamontri et al5 in the validation of the original instrument in English. Using SPI in outpatient clinics specialized in the treatment of psoriasis and the use of the instrument in randomized clinical trials could provide more information on the actual value of the instrument in assessing the severity of the disease and for treatment follow-up.

Footnotes

Work conducted at Complexo Hospitalar Santa Casa de Porto Alegre, Porto Alegre (RS), Brazil; Hospital Universitário de Brasília, Universidade de Brasília, Brasília (DF), Brazil.

Financial support: None.

Conflict of interest: None.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

Marina Resener de Morais

0000-0003-4218-4461

Approval of the final version of the manuscript, Elaboration and writing of the manuscript, Obtaining, analyzing and interpreting the data, Critical review of the literature, Critical review of the manuscript

Gladys Aires Martins

0000-0001-9913-2238

Conception and planning of the study, Obtaining, analyzing and interpreting the data, Intellectual participation in propaedeutic and/or therapeutic conduct of the cases studied

Ricardo Romiti

0000-0003-0165-3831

Conception and planning of the study, Intellectual participation in propaedeutic and/or therapeutic conduct of the cases studied

Renata Elise Tonoli

0000-0001-8619-0412

Obtaining, analyzing and interpreting the data

André Vicente Esteves Carvalho

0000-0002-0407-538X

Approval of the final version of the manuscript, Conception and planning of the study, Elaboration and writing of the manuscript, Obtaining, analyzing and interpreting the data, Effective participation in research orientation, Intellectual participation in propaedeutic and/or therapeutic conduct of the cases studied, Critical review of the literature, Critical review of the manuscript

REFERENCES

- 1.Marks R, Barton SP, Shuttleworth D, Finlay AY. Assessment of disease progress in psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:235–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oji V, Luger TA. The skin in psoriasis: assessment and challenges. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2015;33:S14–S19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krueger G, Koo J, Lebwohl M, Menter A, Stern RS, Rolstad T. The impact of psoriasis on quality of life: results of a 1998 National Psoriasis Foundation patientmembership survey. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:280–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finlay AY. Quality of life measurement in dermatology: a practical guide. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:305–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)--a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chularojanamontri L, Griffiths CEM, Chalmers RJG. Responsiveness to change and interpretability of the simplified psoriasis index. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:351–358. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chularojanamontri L, Griffiths CEM, Chalmers RJG. The Simplified Psoriasis Index (SPI) a practical tool for assessing psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:1956–1962. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]