Dear Editor,

Onychomycosis is one of the most important nail fungal infections in the world. Dermatophytes are the most common fungal agent, with Trichophyton rubrum being the most prevalent. The prevalence of T. rubrum is due to its high virulence and keratinophilic nature. This agent is also the species most adaptable to humans, causing chronic diseases.1 Transmission of onychomycosis occurs through direct or indirect contact with contaminated objects. The role of nail tools in transmitting dermatophytes is known, though there are few studies discussing the possibility of fungal transmission through nail polishes. Hence, this study aimed to analyze the viability of Trichophyton rubrum in nail polishes, base coat and top coat, which were experimentally contaminated, after different periods of time.

This study used a clinical strain of Trichophyton rubrum from the fungal collection of the Mycology Laboratory of the School of Medicine, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande (FURG). T. rubrum was incubated for 7 days at 25º C in potato agar (PDA) to obtain a young culture. After this period, the fungal inoculum was standardized according to the protocol M38-A2 (CLSI).2 The inoculum concentration was adjusted to 2-6x104 CFU/ml, using the Neubauer chamber.

The nail polishes used in this study comprised a red, a white, a base coat, and a top coat from three main commercial brands (“X”, “Y” and “Z”). In a biosafety cabinet, using a sterile pipette, 3.0-3.5 ml of nail polishes was removed from each bottle, leaving a total volume of 4.5ml. Next, 500µl of the standardized inoculum was added to each bottle (1:10 dilution), resulting in a contamination with 2-6x103 UFC of T. rubrum/ml of nail polishes.

To determine the fungal viability after homogenization, 100µl from each bottle of contaminated nail polish were incubated in duplicate on Petri plates. The samples were spread over Sabouraud agar using their respective nail polish brushes and a Drigalski spatula. The inoculations were performed at time 0 (immediately following contamination and homogenization), at 72 hours, and 60 days post-contamination; the bottles remained closed and stored at room temperature until the end of the experiment. The plates were incubated at 25º C, with daily readings and evaluation of growth until 15 days after incubation to assess the retrocultures of the microorganism.

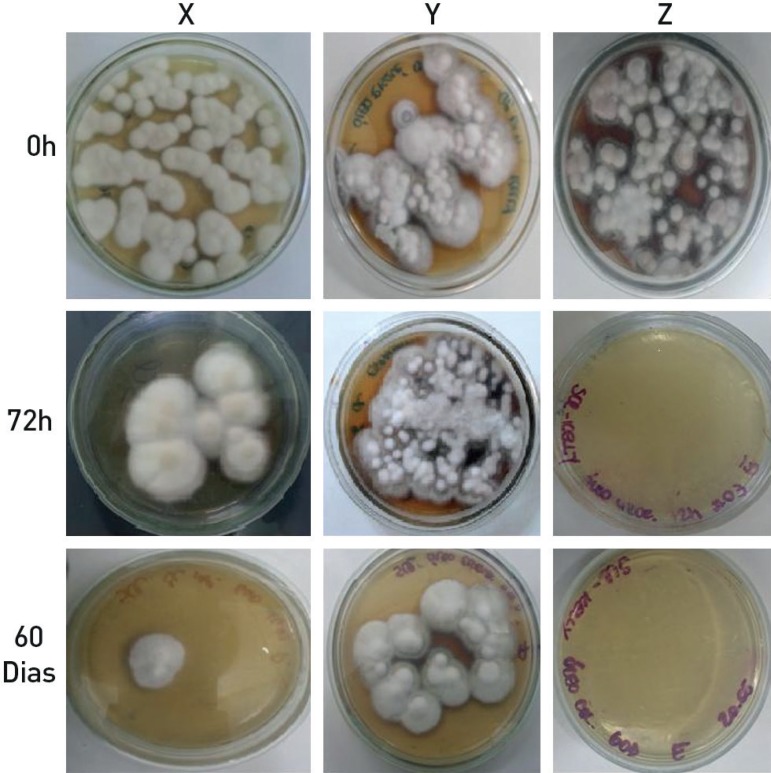

Fungal growth was not observed on the plates inoculated with either the red or white contaminated nail polishes, nor with the contaminated base coat, at any testing time (0, 72 hours and 60 days). In contrast, positive retrocultures of T. rubrum were found in the top coat of all brands (“X”, “Y” and “Z”) at time 0, and of two brands at 72 hours and 60 days (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Fungal growth in top coat samples of brands X, Y and Z, tested at time 0, 72 hours and 60 days

This study has shown the capacity for T. rubrum development in top coat, even 60 days after inoculation. These results are consistent with the study of Gonçalves et al.,3 in which tested nail polishes showed fungal growth after 30 days. These findings emphasize the possibility for top coat to act as a fomite, confirming its significance in the dispersal and indirect transmission of onychomycosis.

Given that the clinical features of onychomycosis include frequent and often abundant peeling of the nails, abrasion of the polish brush on an affected nail would probably be sufficient to carry a fragment of infected keratin to the entire bottle. This would maintain fungal viability, as keratin is the main substrate on which dermatophytes develop. In our study, T. rubrum was able to grow in top coat even in the absence of keratin.

In contrast, the red and white nail polishes and the base coat inhibited T. rubrum growth at all analyzed times. The difference in fungal growth between the tested nail polishes could be due to differences in their chemical features. Most of the top coats marketed in Brazil contain mineral oil and soy oil; red/white nail polishes and base coats, however, do not contain these substances, but do contain highly toxic chemicals such as toluene, xylene, formaldehyde, chromium and nickel. Furthermore, the preservatives and biocides commonly present in aqueous cosmetics, such as sodium benzoate, potassium sorbate, benzoic acid and phenols, decrease microorganism contamination. These substances are not added to oil-based cosmetics.4

Various in vivo conditions predispose onychomycosis by dermatophytes, including aspects inherent to the host (skin health; genetic characteristics; individual habits and customs).5 However, the viability of dermatophytes in top coat, as described in this study, suggests that the propagation and dispersal of this pathogen in the population can be reduced through an important prevention measure: avoidance of sharing personal cosmetic items.

Footnotes

Work conducted at the Mycology Laboratory, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande, Rio Grande (RS), Brazil.

Financial support: None.

Conflict of interest: None.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

Gabriel Baracy Klafke

0000-0002-1397-4926

Conception and planning of the study, Elaboration and writing of the manuscript, Obtaining, analyzing and interpreting the data

Raiza Alves da Silva

0000-0001-9967-6390

Conception and planning of the study, Elaboration and writing of the manuscript, Obtaining, analyzing and interpreting the data

Kelly Thaís de Pellegrin

0000-0002-0119-712X

Conception and planning of the study, Elaboration and writing of the manuscript, Obtaining, analyzing and interpreting the data

Melissa Orzechowski Xavier

0000-0002-3883-0080

Approval of the final version of the manuscript, Conception and planning of the study, Elaboration and writing of the manuscript, Obtaining, analyzing and interpreting the data, Effective participation in research orientation, Critical review of the literature, Critical review of the manuscript

REFERENCES

- 1.Chinnapun D. Virulence Factors Involved in Pathogenicity of Dermatophytes. Walailak J Sci & Tech. 2015;12:573–580. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute . Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Filamentous Fungi, Approved Standard - Second edition. CLSI document M38-A2. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI); 2008. pp. 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gonçalves MG, Castilho EM, Gomes CT, Brizzotti NS, Zen JP, Almeida MTG. Nail polishes Vehicle for transmission the onychomycosis? In: Abstracts of the 18º Congress of the International Society for Human and Animal Mycology, 11-15 June 2012, Berlin, Germany. Mycoses. 2012;55:95–338. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galembeck F, Csordas Y. Cosméticos: a química da beleza. [2017 out 24]. Ccead.puc-rio.br [Internet] Available: http://web.ccead.puc-rio.br/condigital/mvsl/Sala%20de%20Leitura/conteudos/SL_cosmeticos.pdf.

- 5.Criado PR, de Oliveira CB, Dantas KC, Takiguti FA, Benini LV, Vasconcellos C. Superficial mycosis and the immune response elements. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:726–731. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962011000400015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]