Abstract

Background

Dermatological diseases are among the primary causes of the demand for basic health care. Studies on the frequency of dermatoses are important for the proper management of health planning.

Objectives

To evaluate the nosological and behavioral profiles of dermatological consultations in Brazil.

Methods

The Brazilian Society of Dermatology invited all of its members to complete an online form on patients who sought consultations from March 21-26, 2018. The form contained questions about patient demographics, consultation type according to the patient's funding, the municipality of the consultation, diagnosis, treatments and procedures. Diagnostic and therapeutic decisions were compared between subgroups.

Results

Data from 9629 visits were recorded. The most frequent causes for consultation were acne (8.0%), photoaging (7.7%), nonmelanoma skin cancer (5.4%), and actinic keratosis (4.7%). The identified diseases had distinct patterns with regard to gender, skin color, geographic region, type of funding for the consultation, and age group. Concerning the medical conducts, photoprotection was indicated in 44% of consultations, surgical diagnostic procedures were performed in 7.3%, surgical therapeutic procedures were conducted in 19.2%, and cosmetic procedures were performed in 7.1%.

Study limitations

Nonrandomized survey, with a sample period of one week.

Conclusion

This research allowed us to identify the epidemiological profiles of the demands of outpatients for dermatologists in various contexts. The results also highlight the importance of aesthetic demands in privately funded consultations and the significance of diseases such as acne, nonmelanoma skin cancer, leprosy, and psoriasis to public health.

Keywords: Dermatology, Diagnosis, Epidemiology, Therapeutics

INTRODUCTION

Dermatological diseases are frequent among those who seek health care and are among the initial causes of the demand for outpatient services.1 Because they are often visible to others, they are a source of embarrassment and social rejection, leading to psychological suffering.2,3 Although certain dermatological diseases can be treated in the primary care setting, many require specialized care.4

A 2017 publication reported that in the US, the burden of dermatological diseases is high and that its direct and indirect costs are comparable with those of other diseases, such as diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. This tremendous expense is due to the implementation of treatments-not to the diagnostic phase. Overall, 1 in 4 individuals of all ages in the US were seen by a doctor for at least 1 skin disease in 2013. In 2013, skin diseases resulted in direct health costs of 75 billion USD and, indirectly, opportunity costs of 11 billion USD in the US. 5

Skin diseases place a huge burden on global health. Collectively, skin conditions were the fourth leading cause of nonfatal disease burden, expressed in years lost due to disability, in 2010. Taking into account the loss of health due to premature death, expressed in disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), skin is the 18th leading cause. Based on the distribution of dermatological diseases by age, DALYs peak between age 10 and 20 years due to acne and at age 60 years due to nonmelanoma skin cancers.1

However, there is a trend toward the nonvalorization of such diseases by those who are responsible for defining health care policies, due to the underestimation of their lethality and morbidity as a health problem. Several studies have shown that dermatological diseases have a significant impact on the quality of life of those who are affected, especially those who are chronically ill, highlighting the need for their valorization as a health issue by those who formulate public policies, because they are, in fact, valued by affected patients. Individuals with dermatological diseases perceive their health to be affected, feel limited in performing their daily tasks, and experience a loss of vitality, lowering their quality of life.6-14 Dermatological diseases are therefore limiting, causing school and work absenteeism, and their carriers are more likely to experience anxiety and depression.3,15-17

Studies on the distribution of these diseases are important for the proper management of health planning, with regard to health plans and the Brazilian public health care system (SUS). The incorporation of new procedures, in association with an aging population, is contributing to the rise in the demand for and cost of care in dermatology.

In 2018, the Brazilian Society of Dermatology (SBD) conducted a survey on diagnoses and procedures that were performed during dermatological consultations, advancing the initiative that was begun in 2006, when the nosological profile of consultations was published.18

METHODS

The SBD invited all 8800 dermatologists who were current members to participate in the study, which consisted of the completion of an online form on all patients who were treated from May 21-26, 2018-the same week of the study that was conducted in 2006.18 The form included the patient's age, gender, and skin color; city and state size; ICD-10 diagnosis; and their procedures.

For the analysis, certain related diseases were grouped, such as all superficial fungal infections, contact dermatitis, nonmelanoma skin cancers (basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma), and the ectoparasitoses. We also created the category “Others,” which incorporated the diagnoses that were to be elucidated and those diseases with an occurrence of less than 10 cases in the sample.

The main outcome was the frequency of diagnoses that were established at each consultation. Multinomial confidence intervals (95%) were calculated from 10,000 bootstrap replications.19

To evaluate the statistical significance of the univariate analyses of the diagnoses by gender, we applied Spearman's rank correlation coefficient to the entire set of diagnoses from each table.

To examine the association of known variables with frequent and important diagnoses with regard to public health, we hypothesized a case control study with an outpatient basis, in which the main diagnosis corresponded to the cases, while the other diagnoses corresponded to the controls. We then estimated the association, based on the adjusted odds ratio by multivariate logistic regression. 20

The study was approved by the research ethics committee of UNESP (nº 2.668.226).

RESULTS

Eight hundred eighty-five dermatologists completed the survey, which corresponds to 10% of the members of the Society at the time. Data were collected from 9629 consultations, with 13,293 diagnoses, wherein 61.9% of patients had only 1 diagnosis, 29.7% had 2, 7.7% had 3, and 0.7% had 4.

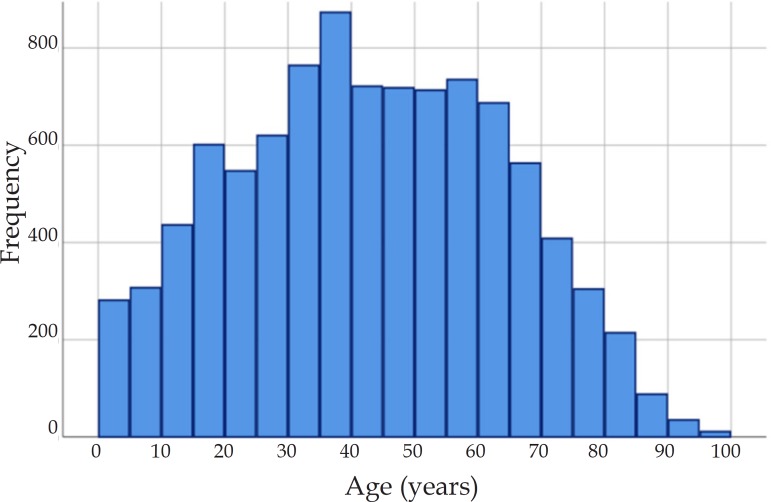

The 9629 patients had a mean (standard deviation) age of 42.8 (21.1) years (Figure 1); 65.1% (6266) was female, and 68.6% (6601) was Caucasian. Regarding funding for the consultation, 48.7% (4685) was financed by health plans, 25.0% (2409) was privately (out of pocket) funded, and 26.3% (2535) was funded by the SUS.

Figure 1.

Age histogram of attended patients (n = 9627)

Table 1 shows the 60 most frequent diagnoses in the consultations, corresponding to 98.3% of attended cases. Acne was the most frequent diagnosis (8.0%), followed by photoaging (7.7%), nonmelanoma skin cancer (6.6%), actinic keratosis (4.7%), and superficial mycoses (4.5%).

Table 1.

Main diagnoses of dermatological consultations (n = 9629)

| Diagnosis | N | % | 95% CI* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Acne | 771 | 8.0 | 7.5 -8.6 |

| 2 | Photoaging /Skin aging | 746 | 7.7 | 7.2-8.3 |

| 3 | Nonmelanoma skin cancer | 633 | 6.6 | 6.1-7.1 |

| 4 | Actinic keratosis / Actinic cheilitis | 451 | 4.7 | 4.3-5.1 |

| 5 | Superficial mycosis (tinea versicolor, dermatophytosis, onychomycosis) | 437 | 4.5 | 4.1-5.0 |

| 6 | Psoriasis | 421 | 4.4 | 4.0-4.8 |

| 7 | Melasma | 357 | 3.7 | 3.3-4.1 |

| 8 | Others** | 349 | 3.6 | 3.3-4.1 |

| 9 | Melanocytic nevus | 333 | 3.5 | 3.1-3.8 |

| 10 | Atopic dermatitis | 326 | 3.4 | 3.0-3.8 |

| 11 | Contact dermatitis (allergic, irritant) | 325 | 3.4 | 3.0-3.7 |

| 12 | Male or female pattern androgenetic alopecia | 307 | 3.2 | 2.8-3.5 |

| 13 | Seborrheic keratosis | 300 | 3.1 | 2.8-3.5 |

| 14 | Acne in adult women | 250 | 2.6 | 2.3-2.9 |

| 15 | Seborrheic dermatitis | 223 | 2.3 | 2.0-2.6 |

| 16 | Viral wart | 207 | 2.1 | 1.9-2.5 |

| 17 | Telogen effluvium | 196 | 2.0 | 1.8-2.3 |

| 18 | Epidermal cyst / trichilemmal cyst | 169 | 1.8 | 1.5-2.0 |

| 19 | Acrochordon (skin tag) / molluscum pendulum | 167 | 1.7 | 1.5-2.0 |

| 20 | Vitiligo | 158 | 1.6 | 1.4-1.9 |

| 21 | Leprosy | 137 | 1.4 | 1.2-1.7 |

| 22 | Rosacea | 124 | 1.3 | 1.1-1.5 |

| 23 | Alopecia areata | 120 | 1.2 | 1.0-1.5 |

| 24 | Folliculitis | 110 | 1.1 | 0.9-1.4 |

| 25 | Cutaneous xerosis / Asteatosis | 106 | 1.1 | 0.9-1.3 |

| 26 | Hypertrophic scar/Keloid | 97 | 1.0 | 0.8-1.2 |

| 27 | Lichen simplex chronicus/ Prurigo / Chronic eczema | 94 | 1.0 | 0.8-1.2 |

| 28 | Pruritus (sine materiae) | 85 | 0.9 | 0.7-1.1 |

| 29 | Scabies / Pediculosis | 84 | 0.9 | 0.7-1.1 |

| 30 | Solar lentigo / Solar melanosis | 83 | 0.9 | 0.7-1.1 |

| 31 | Cicatricial alopecia (lupus, folliculitis decalvans, lichen planus pilaris) | 82 | 0.9 | 0.7-1.0 |

| 32 | Urticaria /Angioedema | 73 | 0.8 | 0.6-0.9 |

| 33 | Molluscum contagiosum | 71 | 0.7 | 0.6-0.9 |

| 34 | Melanoma | 64 | 0.7 | 0.5-0.8 |

| 35 | Post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation | 63 | 0.7 | 0.5-0.8 |

| 36 | Cutaneous lupus erythematosus | 60 | 0.6 | 0.5-0.8 |

| 37 | Striae distansae | 58 | 0.6 | 0.5-0.8 |

| 38 | Chronic lower limb ulcer | 58 | 0.6 | 0.4-0.8 |

| 39 | Impetigo and ecthyma | 55 | 0.6 | 0.4-0.7 |

| 40 | Drug eruptions | 53 | 0.6 | 0.4-0.7 |

| 41 | Onycholysis / Onychomadesis/ Onychomalacia / Onychodystrophy | 53 | 0.6 | 0.4-0.7 |

| 42 | Acne scar | 49 | 0.5 | 0.4-0.7 |

| 43 | Pemphigus and pemphigoid | 46 | 0.5 | 0.3-0.6 |

| 44 | Anogenital warts (HPV) / Condyloma | 44 | 0.5 | 0.3-0.6 |

| 45 | Keratosis pilaris | 43 | 0.4 | 0.3-0.6 |

| 46 | Cutaneous lymphoma and lym- phomatoid proliferations | 42 | 0.4 | 0.3-0.6 |

| 47 | Lipoma | 41 | 0.4 | 0.3-0.6 |

| 48 | Cutaneous / systemic scleroderma | 37 | 0.4 | 0.3-0.5 |

| 49 | Pityriasis rosea | 34 | 0.4 | 0.2-0.5 |

| 50 | Herpes zoster | 31 | 0.3 | 0.2-0.4 |

| 51 | Ingrown toenail / Onychocryptosis | 30 | 0.3 | 0.2-0.4 |

| 52 | Dermatofibroma | 29 | 0.3 | 0.2-0.4 |

| 53 | Genital / extralabial herpes | 25 | 0.3 | 0.2-0.4 |

| 54 | Hidradenitis suppurativa | 24 | 0.2 | 0.2-0.4 |

| 55 | Pityriasis alba | 22 | 0.2 | 0.1-0.3 |

| 56 | Subcutaneous / Systemic mycosis | 21 | 0.2 | 0.1-0.3 |

| 57 | Syringoma / Sweat glands neoplasms | 20 | 0.2 | 0.1-0.3 |

| 58 | Lichen planus | 19 | 0.2 | 0.1-0.3 |

| 59 | Hemangioma | 18 | 0.2 | 0.1-0.3 |

| 60 | Syphilis | 17 | 0.2 | 0.1-0.3 |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval calculated from 10,000 bootstrap replications;

Diagnoses with fewer than 10 occurrences or to be clarified

Tables 2 to 7 present the leading 10 causes by age group, skin color, gender, type of funding for the consultation, type of consultation (first or second appointment) , and demographic region. In these tables, differences were statistically significant between age groups, genders, and types of funding for consultation; there was no significance between the classifications by phototype, type of consultation, and demographic region.

Table 2.

Primary diagnoses by age group

| 0-12 years old | 12-24 years old | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | N | % | Diagnosis | N | % | |

| 1 | Atopic dermatitis | 212 | 25.8 | Acne | 557 | 41.2 |

| 2 | Molluscum contagiosum | 61 | 7.4 | Contact dermatitis | 58 | 4.3 |

| 3 | Viral wart | 55 | 6.7 | Atopic dermatitis | 55 | 4.1 |

| 4 | Acne | 48 | 5.8 | Superficial mycosis | 49 | 3.6 |

| 5 | Others | 34 | 4.1 | Melanocytic nevus | 42 | 3.1 |

| 6 | Superficial mycosis | 32 | 3.9 | Psoriasis | 40 | 3.0 |

| 7 | Melanocytic nevus | 32 | 3.9 | Viral wart | 34 | 2.5 |

| 8 | Scabies / Pediculosis | 29 | 3.5 | Others | 32 | 2.4 |

| 9 | Vitiligo | 29 | 3.5 | Striae distensiae | 31 | 2.3 |

| 10 | Alopecia areata | 24 | 2.9 | Male or female pattern androgenetic alopecia | 31 | 2.3 |

| 11 | Seborrheic dermatitis | 20 | 2.4 | Seborrheic dermatitis | 28 | 2.1 |

| 12 | Contact dermatitis | 19 | 2.3 | Acne in adult women | 28 | 2.1 |

| 13 | Impetigo and ecthyma | 18 | 2.2 | Telogen effluvium | 24 | 1.8 |

| 14 | Psoriasis | 18 | 2.2 | Alopecia areata | 23 | 1.7 |

| 15 | Hemangioma | 14 | 1.7 | Folliculitis | 20 | 1.5 |

| 16 | Diaper dermatitis | 14 | 1.7 | Vitiligo | 19 | 1.4 |

| 17 | Pityriasis alba | 14 | 1.7 | Hypertrophic scar | 19 | 1.4 |

| 18 | Lichen simplex chronicus | 12 | 1.5 | Scabies / Pediculosis | 15 | 1.1 |

| 19 | Xerosis / Asteatosis | 11 | 1.3 | Epidermoid cysts | 15 | 1.1 |

| 20 | Keratosis pilaris | 9 | 1.1 | Urticaria | 14 | 1.0 |

| 25-59 years old | 60 years and older | |||||

| Diagnosis | N | % | Diagnosis | N | % | |

| 1 | Photoaging | 540 | 10.5 | Nonmelanoma skin cancer | 446 | 19.3 |

| 2 | Melasma | 341 | 6.6 | Actinic keratosis | 299 | 12.9 |

| 3 | Psoriasis | 251 | 4.9 | Photoaging | 202 | 8.7 |

| 4 | Superficial mycosis | 244 | 4.7 | Seborrheic keratosis | 144 | 6.2 |

| 5 | Melanocytic nevus | 225 | 4.4 | Psoriasis | 112 | 4.8 |

| 6 | Male or female pattern androgenetic alopecia | 221 | 4.3 | Superficial mycosis | 112 | 4.8 |

| 7 | Acne in adult women | 220 | 4.3 | Contact dermatitis | 78 | 3.4 |

| 8 | Others | 208 | 4.0 | Others | 75 | 3.2 |

| 9 | Nonmelanoma skin cancer | 179 | 3.5 | Male or female pattern androgenetic alopecia | 52 | 2.3 |

| 10 | Contact dermatitis | 170 | 3.3 | Pruritus (sine materiae) | 44 | 1.9 |

| 11 | Acne | 156 | 3.0 | Acrochordon /skin tag | 42 | 1.8 |

| 12 | Seborrheic keratosis | 149 | 2.9 | Epidermoid cysts | 42 | 1.8 |

| 13 | Actinic keratosis | 149 | 2.9 | Lower limb ulcer | 38 | 1.6 |

| 14 | Seborrheic dermatitis | 143 | 2.8 | Xerosis / Asteatosis | 35 | 1.5 |

| 15 | Telogen effluvium | 141 | 2.7 | Melanocytic nevus | 34 | 1.5 |

| 16 | Acrochordon /skin tag | 116 | 2.3 | Seborrheic dermatitis | 32 | 1.4 |

| 17 | Epidermoid cysts | 109 | 2.1 | Leprosy | 32 | 1.4 |

| 18 | Vitiligo | 95 | 1.8 | Rosacea | 30 | 1.3 |

| 19 | Viral wart | 90 | 1.7 | Solar lentigo / Solar melanosis | 30 | 1.3 |

| 20 | Leprosy | 88 | 1.7 | Telogen effluvium | 29 | 1.3 |

Spearman rank R: -0.07 t=-7.23 p<0.01

Table 7.

Distribution of diagnoses by region in Brazil

| North | Northeast | Southeast | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | N | % | Diagnosis | N | % | Diagnosis | N | % | ||

| 1 | Acne | 110 | 7.6 | Photoaging | 52 | 10.9 | Photoaging | 374 | 8.6 | |

| 2 | Atopic dermatitis | 72 | 5.0 | Acne | 38 | 8.0 | Acne | 336 | 7.7 | |

| 3 | Superficial mycosis | 63 | 4.4 | Leprosy | 24 | 5.0 | NM skin cancer | 281 | 6.5 | |

| 4 | Melasma | 63 | 4.4 | NM skin cancer | 23 | 4.8 | Superficial mycosis | 224 | 5.2 | |

| 5 | NM skin cancer | 61 | 4.2 | Melasma | 20 | 4.2 | Psoriasis | 205 | 4.7 | |

| 6 | Others | 56 | 3.9 | Psoriasis | 20 | 4.2 | Actinic keratosis | 186 | 4.3 | |

| 7 | Contact dermatitis | 54 | 3.8 | Superficial mycosis | 18 | 3.8 | Others | 180 | 4.1 | |

| 8 | Photoaging | 48 | 3.3 | Atopic dermatitis | 17 | 3.6 | Melasma | 154 | 3.5 | |

| 8 | Psoriasis | 44 | 3.1 | Seborrheic keratosis | 17 | 3.6 | Melanocytic nevus | 149 | 3.4 | |

| 10 | Acrochordon /skin tag | 44 | 3.1 | Acne in adult women | 16 | 3.4 | Contact dermatitis | 135 | 3.1 | |

| 11 | Seborrheic dermatitis | 43 | 3.0 | Male or female pattern androgenetic alopecia | 15 | 3.2 | Atopic dermatitis | 134 | 3.1 | |

| 12 | Scabies / Pediculosis | 42 | 2.9 | Actinic keratosis | 15 | 3.2 | Seborrheic keratosis | 130 | 3.0 | |

| 13 | Male or female pattern androgenetic alopecia | 39 | 2.7 | Seborrheic dermatitis | 14 | 2.9 | Male or female pattern androgenetic alopecia | 129 | 3.0 | |

| 14 | Epidermoid cysts | 39 | 2.7 | Contact dermatitis | 13 | 2.7 | Acne in adult women | 104 | 2.4 | |

| 15 | Acne in adult women | 36 | 2.5 | Acrochordon /skin tag | 12 | 2.5 | Viral wart | 104 | 2.4 | |

| 16 | Melanocytic nevus | 33 | 2.3 | Melanocytic nevus | 12 | 2.5 | Seborrheic dermatitis | 100 | 2.3 | |

| 17 | Seborrheic keratosis | 30 | 2.1 | Others | 11 | 2.3 | Telogen effluvium | 89 | 2.0 | |

| 18 | Actinic keratosis | 28 | 1.9 | Epidermoid cysts | 9 | 1.9 | Epidermoid cysts | 80 | 1.8 | |

| 19 | Telogen effluvium | 26 | 1.8 | Viral wart | 9 | 1.9 | Vitiligo | 65 | 1.5 | |

| 20 | Viral wart | 26 | 1.8 | Telogen effluvium | 8 | 1.7 | Leprosy | 62 | 1.4 | |

| South | Midwest | |||||||||

| Diagnosis | N | % | Diagnosis | N | % | |||||

| 1 | NM skin cancer | 195 | 8.9 | Acne | 119 | 9.8 | ||||

| 2 | Photoaging | 185 | 8.5 | Photoaging | 87 | 7.1 | ||||

| 3 | Actinic keratosis | 171 | 7.8 | NM skin cancer | 73 | 6.0 | ||||

| 4 | Acne | 168 | 7.7 | Superficial mycosis | 56 | 4.6 | ||||

| 5 | Psoriasis | 105 | 4.8 | Male or female pattern androgenetic alopecia | 55 | 4.5 | ||||

| 6 | Melanocytic nevus | 100 | 4.6 | Acne in adult women | 54 | 4.4 | ||||

| 7 | Seborrheic keratosis | 79 | 3.6 | Contact dermatitis | 51 | 4.2 | ||||

| 8 | Superficial mycosis | 76 | 3.5 | Actinic keratosis | 51 | 4.2 | ||||

| 9 | Contact dermatitis | 72 | 3.3 | Melasma | 49 | 4.0 | ||||

| 10 | Melasma | 71 | 3.2 | Psoriasis | 47 | 3.9 | ||||

| 11 | Male or female pattern androgenetic alopecia | 69 | 3.2 | Seborrheic keratosis | 44 | 3.6 | ||||

| 12 | Others | 66 | 3.0 | Melanocytic nevus | 39 | 3.2 | ||||

| 13 | Atopic dermatitis | 65 | 3.0 | Atopic dermatitis | 38 | 3.1 | ||||

| 14 | Viral wart | 52 | 2.4 | Others | 36 | 3.0 | ||||

| 15 | Vitiligo | 51 | 2.3 | Seborrheic dermatitis | 30 | 2.5 | ||||

| 16 | Telogen effluvium | 49 | 2.2 | Acrochordon / skin tag | 25 | 2.0 | ||||

| 17 | Rosacea | 48 | 2.2 | Alopecia areata | 25 | 2.0 | ||||

| 18 | Acne in adult women | 40 | 1.8 | Telogen effluvium | 24 | 2.0 | ||||

| 19 | Seborrheic dermatitis | 36 | 1.6 | Leprosy | 21 | 1.7 | ||||

| 20 | Acrochordon /skin tag | 30 | 1.4 | Cicatricial alopecia | 17 | 1.4 | ||||

Spearman rank R: -0.01 t=-0.08 p=0.94

Table 3.

Main diagnoses by skin color

| COLOR - White | COLOR - Non-white | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | N | % | Diagnosis | N | % | |

| 1 | Photoaging | 628 | 9.5 | Acne | 225 | 7.4 |

| 2 | Nonmelanoma skin cancer | 564 | 8.5 | Superficial mycosis | 175 | 5.8 |

| 3 | Acne | 546 | 8.3 | Melasma | 168 | 5.5 |

| 4 | Actinic keratosis | 418 | 6.3 | Psoriasis | 159 | 5.3 |

| 5 | Melanocytic nevus | 281 | 4.3 | Atopic dermatitis | 128 | 4.2 |

| 6 | Superficial mycosis | 262 | 4.0 | Photoaging | 118 | 3.9 |

| 7 | Psoriasis | 262 | 4.0 | Contact dermatitis | 116 | 3.8 |

| 8 | Others | 246 | 3.7 | Others | 103 | 3.4 |

| 9 | Seborrheic keratosis | 215 | 3.3 | Acne in adult women | 97 | 3.2 |

| 10 | Male or female pattern androgenetic alopecia | 211 | 3.2 | Seborrheic dermatitis | 97 | 3.2 |

| 11 | Contact dermatitis | 209 | 3.2 | Male or female pattern androgenetic alopecia | 96 | 3.2 |

| 12 | Atopic dermatitis | 198 | 3.0 | Leprosy | 91 | 3.0 |

| 13 | Melasma | 189 | 2.9 | Seborrheic keratosis | 85 | 2.8 |

| 14 | Acne in adult women | 153 | 2.3 | Acrochordon / skin tag | 70 | 2.3 |

| 15 | Viral wart | 142 | 2.2 | Nonmelanoma skin cancer | 69 | 2.3 |

| 16 | Telogen effluvium | 138 | 2.1 | Viral wart | 65 | 2.1 |

| 17 | Seborrheic dermatitis | 126 | 1.9 | Epidermoid cysts | 63 | 2.1 |

| 18 | Rosacea | 113 | 1.7 | Telogen effluvium | 58 | 1.9 |

| 19 | Epidermoid cysts | 106 | 1.6 | Vitiligo | 58 | 1.9 |

| 20 | Vitiligo | 100 | 1.5 | Alopecia areata | 56 | 1.8 |

Spearman rank R: 0.01 t=0.815 p=0.42.

Table 4.

Distribution of diagnoses by gender

| Female | Male | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | N | % | Diagnosis | N | % | |

| 1 | Photoaging | 682 | 10.9 | Acne | 385 | 11.4 |

| 2 | Acne | 386 | 6.2 | Nonmelanoma skin cancer | 312 | 9.3 |

| 3 | Melasma | 335 | 5.3 | Actinic keratosis | 193 | 5.7 |

| 4 | Nonmelanoma skin cancer | 321 | 5.1 | Superficial mycosis | 192 | 5.7 |

| 5 | Actinic keratosis | 258 | 4.1 | Psoriasis | 180 | 5.4 |

| 6 | Superficial mycosis | 245 | 3.9 | Atopic dermatitis | 138 | 4.1 |

| 7 | Acne in adult women | 243 | 3.9 | Melanocytic nevus | 128 | 3.8 |

| 8 | Psoriasis | 241 | 3.8 | Others | 109 | 3.2 |

| 9 | Others | 240 | 3.8 | Seborrheic dermatitis | 105 | 3.1 |

| 10 | Contact dermatitis | 224 | 3.6 | Contact dermatitis | 101 | 3.0 |

| 11 | Male or female pattern androgenetic alopecia | 206 | 3.3 | Androgenetic alopecia | 101 | 3.0 |

| 12 | Seborrheic keratosis | 206 | 3.3 | Seborrheic keratosis | 94 | 2.8 |

| 13 | Melanocytic nevus | 205 | 3.3 | Viral wart | 86 | 2.6 |

| 14 | Atopic dermatitis | 188 | 3.0 | Leprosy | 76 | 2.3 |

| 15 | Telogen effluvium | 187 | 3.0 | Acrochordon /skin tag | 71 | 2.1 |

| 16 | Viral wart | 121 | 1.9 | Photoaging | 64 | 1.9 |

| 17 | Seborrheic dermatitis | 118 | 1.9 | Alopecia areata | 64 | 1.9 |

| 18 | Vitiligo | 115 | 1.8 | Epidermoid cysts | 61 | 1.8 |

| 19 | Epidermoid cysts | 108 | 1.7 | Folliculitis | 53 | 1.6 |

| 20 | Acrochordon /skin tag | 96 | 1.5 | Vitiligo | 43 | 1.3 |

Spearman rank R: -0.15 t=-15.00 p<0.01

Table 6.

Distribution of diagnoses by type of consultation

| FIRST APPOINTMENT | SECOND APPOINTMENT | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | N | % | Diagnosis | N | % | |

| 1 | Acne | 386 | 8.2 | Photoaging | 260 | 9.9 |

| 2 | Superficial mycosis | 282 | 6.0 | Acne | 386 | 7.9 |

| 3 | Photoaging | 260 | 5.5 | Nonmelanoma skin cancer | 255 | 7.7 |

| 4 | Nonmelanoma skin cancer | 255 | 5.4 | Psoriasis | 115 | 6.2 |

| 5 | Contact dermatitis | 202 | 4.3 | Actinic keratosis | 190 | 5.3 |

| 6 | Atopic dermatitis | 197 | 4.2 | Others | 160 | 3.9 |

| 7 | Seborrheic keratosis | 197 | 4.2 | Melasma | 170 | 3.8 |

| 8 | Actinic keratosis | 190 | 4.0 | Male or female pattern androgenetic alopecia | 140 | 3.4 |

| 9 | Melanocytic nevus | 189 | 4.0 | Superficial mycosis | 282 | 3.2 |

| 10 | Melasma | 170 | 3.6 | Melanocytic nevus | 189 | 2.9 |

| 11 | Others | 160 | 3.4 | Atopic dermatitis | 197 | 2.6 |

| 12 | Seborrheic dermatitis | 148 | 3.1 | Contact dermatitis | 202 | 2.5 |

| 13 | Acne in adult women | 146 | 3.1 | Viral wart | 90 | 2.4 |

| 14 | Male or female pattern androgenetic alopecia | 140 | 3.0 | Acne in adult women | 146 | 2.1 |

| 15 | Telogen effluvium | 120 | 2.5 | Seborrheic keratosis | 197 | 2.1 |

| 16 | Psoriasis | 115 | 2.4 | Leprosy | 36 | 2.1 |

| 17 | Acrochordon / skin tag | 99 | 2.1 | Vitiligo | 61 | 2.0 |

| 18 | Epidermoid cysts | 93 | 2.0 | Telogen effluvium | 120 | 1.6 |

| 19 | Viral wart | 90 | 1.9 | Epidermoid cysts | 93 | 1.6 |

| 20 | Xerosis / Asteatosis | 72 | 1.5 | Seborrheic dermatitis | 148 | 1.5 |

Spearman Rank R: 0.01 t=0.95 p=0.34

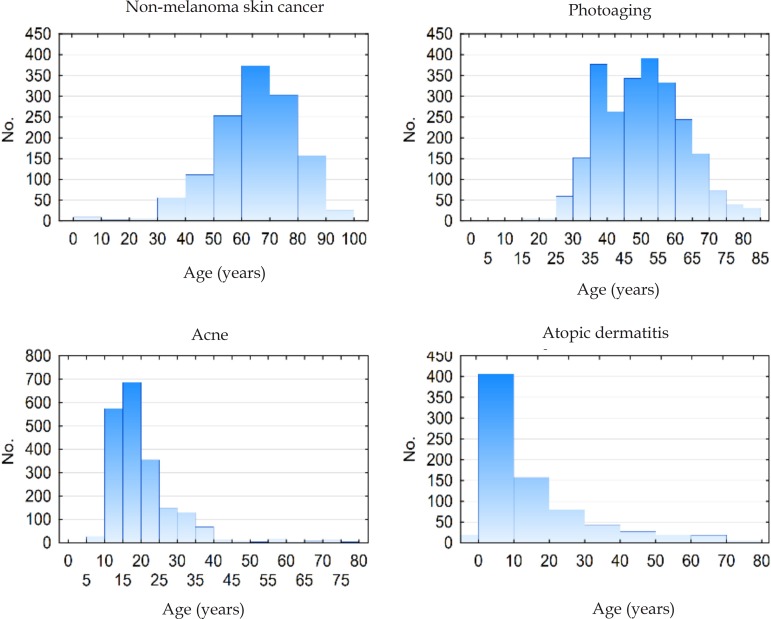

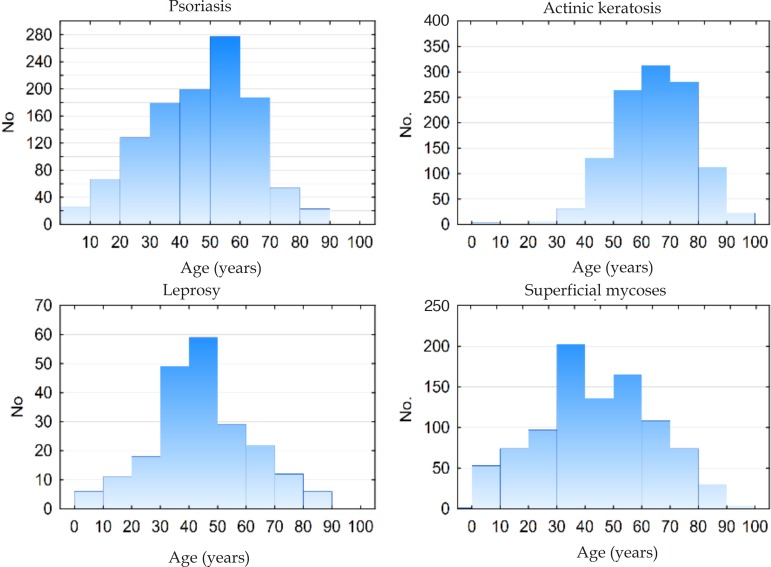

Figure 2 shows the age histograms of the frequency of atopic dermatitis, acne, nonmelanoma skin cancer, and photoaging; Figure 3 shows the age histograms for superficial mycoses, leprosy, actinic keratosis, and psoriasis.

Figure 2.

Age histograms for patients diagnosed with atopic dermatitis, acne, nonmelanoma skin cancer, and photoaging

Figure 3.

Age histograms for patients diagnosed with superficial mycoses, Hansen disease, actinic keratosis, and psoriasis

With regard to skin color, diagnoses of photoaging (9.5%), nonmelanoma skin cancer (8.5%), and acne (8.3%) were more frequent among whites, compared with acne (7.4%), superficial mycoses (5.8%), and melasma (5.5%), in non-whites. Although acne was the third most common condition in whites, its frequency was higher among non-whites. This phenomenon resulted non-significant regarding the ordination (rank) distribution, although diagnoses of photoaging and nonmelanoma skin cancer were more frequent among whites.

Between genders, women were most frequently diagnosed with photoaging (10.9%) and acne (6.2%), versus acne (11.4%) and nonmelanoma skin cancer (9.3%) in men, confirming that the demand for dermatological care for aesthetic reasons is greater in females.

Regarding infectious diseases, the most frequent diagnosis was superficial mycoses, with 437 cases (4.5%). Moreover, 44 (0.5%) patients had a diagnosis of genital warts, 137 (1.4%) had leprosy, 61 (0.6%) had syphilis, 84 (0.9%) had scabies / pediculosis, and 71 (0.7%) had molluscum contagiosum.

When we considered all consultation-based diagnoses - not only the main diagnosis - the most relevant result was the increase in the proportion of patients who were affected by the most common diseases. For example, 48.4% of patients aged between 13 and 24 years had a diagnosis of acne, and 24.1% of those aged 60 years and older had a diagnosis of nonmelanoma skin cancer, whereas these diseases were the chief diagnoses in the consultations in 41.2% and 19.3% of the age groups above.

Table 8 shows the most frequent standard treatments and the proportion of patients to whom they were administered. Table 9 shows the practices and the proportion of patients by funding type. Notably, each patient received more than 1 treatment, for example, 2.51 indications on average in consultations funded by health plans, compared with 2.61 for private funding and 2.16 for SUS-funded consultations.

Table 8.

Frequencies of (standard) treatments resulting from consultations

| CONDUCT | N | % of patients |

|---|---|---|

| Topical Medications1 | 4922 | 51.1 |

| Sunscreen | 4232 | 44.0 |

| Moisturizers and emollients | 3002 | 31.2 |

| Oral medications2 | 2379 | 24.7 |

| Topical cosmeceuticals3 | 1859 | 19.3 |

| Therapeutic surgical procedure4 | 1838 | 19.1 |

| Diagnostic clinical procedure5 | 801 | 8.3 |

| Diagnostic surgical procedure6 | 706 | 7.3 |

| Cosmetic surgical procedure7 | 674 | 7.0 |

| Nutraceuticals, antioxidants and food supplements | 605 | 6.3 |

| Botulinum toxin | 524 | 5.4 |

| Fillers/volumizers | 303 | 3.1 |

| Phototherapy8 | 149 | 1.5 |

| Immunobiologicals9 | 65 | 0.7 |

e.g., corticoid, antifungal, antimicrobial, tretinoin, minoxidil

e.g., antimicrobials, antihistamines, isotretinoin, immunosuppressants

e.g., antioxidants, retinoids, soaps

e.g., electrocoagulation, excision and suturing, cryosurgery

e.g., dermatoscopy, Wood’s lamp, esthesiometer

e.g., biopsy, puncture, mycological examination

e.g., peeling, laser, needling, microdermabrasion

e.g., PUVA, NBUVB, PUVA sun

e.g., anti-TNF, anti-IgE, anti-IL17

Table 9.

Frequencies of (standard) treatments by type of funding for consultation

| CONDUCT / PRESCRIPTION | Coverage / health insurance | Private / Out of pocke | SUS / public | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % of patients | N | % of patients | N | % of patients | ||

| 1 | All procedures | 11741 | 250.6 | 6266 | 260.1 | 5474 | 215.9 |

| 2 | Topical medications | 2657 | 56.7 | 1045 | 43.4 | 1220 | 48.1 |

| 3 | Sunscreen | 2203 | 47.0 | 988 | 41.0 | 1041 | 41.1 |

| 4 | Moisturizers and emollients | 1456 | 31.1 | 672 | 27.9 | 874 | 34.5 |

| 5 | Oral medications | 1056 | 22.5 | 583 | 24.2 | 740 | 29.2 |

| 6 | Topical cosmeceuticals | 1128 | 24.1 | 525 | 21.8 | 206 | 8.1 |

| 7 | Therapeutic surgical procedure | 1012 | 21.6 | 349 | 14.5 | 477 | 18.8 |

| 8 | Diagnostic clinical procedure | 415 | 8.9 | 212 | 8.8 | 174 | 6.9 |

| 9 | Diagnostic surgical procedure | 338 | 7.2 | 126 | 5.2 | 242 | 9.5 |

| 10 | Cosmetic surgical procedure | 181 | 3.9 | 432 | 17.9 | 61 | 2.4 |

| 11 | Nutraceuticals and antioxidants | 355 | 7.6 | 213 | 8.8 | 37 | 1.5 |

| 12 | Botulinum toxin | 134 | 2.9 | 381 | 15.8 | 9 | 0.4 |

| 13 | Fillers/volumizers | 79 | 1.7 | 222 | 9.2 | 2 | 0.1 |

| 14 | Phototherapy | 43 | 0.9 | 46 | 1.9 | 60 | 2.4 |

| 15 | Immunobiologicals | 14 | 0.3 | 18 | 0.7 | 33 | 1.3 |

Spearman rank R: 0.03 t=4.33 p<0.01

Table 10 presents the results of the logistic regression, comparing certain diseases by region in Brazil, gender, age group, and funding type. Leprosy was associated with regional differences, a preponderance of SUS-based care, males the working age group, non-white skin color, and the need for subsequent appointments. The frequency of psoriasis was higher in the south of Brazil, those in the public health care system, males, the economically productive age group, and those who required return visits. Nonmelanoma skin cancers were more common in those who were on public assistance, males, resident of smaller towns, and those with white skin color.

Table 10.

Multivariate analysis (multiple logistic regression) comparing the frequency of Hansen disease, psoriasis, and nonmelanoma skin cancer by region in Brazil, gender, age group, city size, skin color, funding type, and consultation type

| LEPROSY | PSORIASIS | NONMELANOMA CA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR* | p | OR* | p | OR* | p | ||

| Region | N | 2.07 | 0.02 | 0.78 | 0.37 | 1.62 | 0.07 |

| NE | 4.52 | 0.00 | 0.83 | 0.70 | 1.30 | 0.95 | |

| S | 0.25 | 0.00 | 1.16 | 0.02 | 1.22 | 0.60 | |

| MW | 1.24 | 0.99 | 0.74 | 0.17 | 1.35 | 0.66 | |

| SE | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Funding type | Coverage / health insurance | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.31 | 0.00 | 0.32 | 0.00 |

| Private /out of pocket payment | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.42 | 0.03 | 0.42 | 0.01 | |

| SUS | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Gender | Female | 0.44 | 0.00 | 0.69 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.00 |

| Male | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Age group (years) | 0-12 | 0.30 | 0.02 | 0.50 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| 13-24 | 0.78 | 0.95 | 0.72 | 0.37 | 0.02 | 0.00 | |

| 25-59 | 1.50 | 0.00 | 1.24 | 0.00 | 0.19 | 0.00 | |

| >60 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| City | <100,000 inhabitants | 0.74 | 0.53 | 0.57 | 0.24 | 1.62 | 0.01 |

| 100-300,000 inhabitants | 1.07 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.05 | 1.24 | 0.86 | |

| >300,000 inhabitants | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Skin color | White | 0.53 | 0.01 | 0.85 | 0.15 | 3.94 | 0.00 |

| Non-white | 1 | ||||||

| Consultation type | First appointment | 0.51 | 0.00 | 0.47 | 0.00 | 0.98 | 0.83 |

| Second appointment | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

OR: odds ratio

DISCUSSION

Dermatology, as a medical specialty, typically encompasses a high number of nosological entities from skin, mucosae and skin appendages. In parallel, it assists many populations, enclosing all age groups and genders, which, added to the sociocultural, climatic, and ethnic differences of the Brazilian population, results in individualized patterns of disease occurrence.21 All of these elements should be weighed in planning specialty care, public health policies, and medical education.22-26

The most frequent primary diagnosis of the consultations in our study was acne, as well as in a previous report from 2006.18 Actually, acne is the main cause for consultations in Saudi Arabia27 and the US.28 In a study with dermatologists in Spain,4 the most frequent diagnosis was nonmelanoma skin cancer, although acne was the chief diagnosis among those aged under 18 years. The inconsistency between our results and those in Spain is due to the disparate age groups between study populations.

Differences in the occurrence of conditions between ages are expected and are characteristic of the natural history of dermatoses, such as ectoparasitoses and childhood viral infections, in contrast to melasma and acne in adult women and nonmelanoma skin cancers and seborrheic keratosis among the elderly.29-33 Chronic diseases, such as psoriasis and androgenetic alopecia, tend to increase progressively in frequency, depending on the age group.21,34-36 Conversely, more limited diseases, such as acne and atopic dermatitis, become less common in adulthood. Superficial mycoses, in contrast, are frequent in all age groups.

The skin is an organ that interfaces directly with the environment, and external insults can promote several dermatoses. The ethnic and climatic variety in Brazil is considered in the type of epidemiological examination that we performed in this study. Contact dermatitis became frequent in consultations, especially beginning in adolescence, when work activities initiate. Nonmelanoma skin cancer and actinic keratoses were frequent among the elderly, especially those with light skin color who were treated by the public health system, reflecting chronic exposure to ultraviolet radiation in such activities as agriculture and fishing.35,37,38 Melasma was typical in women and non-white adult patients, due to the role of female hormones and miscegenation in its pathogenesis.32,38-41

In comparing our results with those of the 2006 study, which used only the general ICD-10 category codes, a major difference arose between the two sets of patients with regard to the inclusion of patients with a primary diagnosis of photoaging, which reflects the cosmetic demand for dermatologists, especially in private consultations and among white women. When using the same type of coding as in the previous study, a diagnosis of acne (L70) was given to 10.6% (1021) of patients, whereas skin alterations due to chronic exposure to non-ionizing radiation (L57) was diagnosed in 12.4% (1197) of patients, versus 14.0% and 5.1% in the 2006 study, respectively.

Notably, in our study, superficial mycoses were the fifth most frequent diagnosis (4.5%) compared with the second most common diagnosis in the 2006 study (8.7%). This difference is attributed to the finding that in SUS-funded patients, this was the main diagnosis in 2006 (9.8%) but remained the fifth most frequent diagnosis in our subjects (4.8%) (Table 5), likely reflecting a greater capacity for diagnosis and treatment for basic care in the SUS system.

Table 5.

Distribution of diagnoses by type of funding for consultation

| COVERAGE / HEALTH INSURANCE | PRIVATE / OUT OF POCKET PAYMENT | SUS / PUBLIC | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | N | % | Diagnosis | N | % | Diagnosis | N | % | |

| 1 | Acne | 497 | 10.6 | Photoaging | 495 | 20.5 | Nonmelanoma skin cancer | 297 | 11.7 |

| 2 | Superficial mycosis | 261 | 5.6 | Acne | 160 | 6.6 | Psoriasis | 225 | 8.9 |

| 3 | Actinic keratosis | 230 | 4.9 | Nonmelanoma skin cancer | 155 | 6.4 | Leprosy | 131 | 5.2 |

| 4 | Melasma | 227 | 4.8 | Others | 149 | 6.2 | Actinic keratosis | 128 | 5.0 |

| 5 | Photoaging | 201 | 4.3 | Male or female pattern androgenetic alopecia | 114 | 4.7 | Superficial mycosis | 121 | 4.8 |

| 6 | Seborrheic keratosis | 200 | 4.3 | Actinic keratosis | 93 | 3.9 | Acne | 114 | 4.5 |

| 7 | Melanocytic nevus | 187 | 4.0 | Contact dermatitis | 88 | 3.7 | Atopic dermatitis | 90 | 3.6 |

| 8 | Nonmelanoma skin cancer | 181 | 3.9 | Psoriasis | 85 | 3.5 | Others | 83 | 3.3 |

| 9 | Atopic dermatitis | 179 | 3.8 | Melasma | 80 | 3.3 | Melanocytic nevus | 70 | 2.8 |

| 10 | Acne in adult women | 172 | 3.7 | Melanocytic nevus | 76 | 3.2 | Vitiligo | 68 | 2.7 |

| 11 | Contact dermatitis | 171 | 3.6 | Atopic dermatitis | 57 | 2.4 | Contact dermatitis | 66 | 2.6 |

| 12 | Male or female pattern androgenetic alopecia | 154 | 3.3 | Superficial mycosis | 55 | 2.3 | Seborrheic dermatitis | 51 | 2.0 |

| 13 | Seborrheic dermatitis | 140 | 3.0 | Acne in adult women | 55 | 2.3 | Photoaging | 50 | 2.0 |

| 14 | Acrochordon /skin tag | 138 | 2.9 | Seborrheic keratosis | 51 | 2.1 | Melasma | 50 | 2.0 |

| 15 | Telogen effluvium | 137 | 2.9 | Rosacea | 46 | 1.9 | Seborrheic keratosis | 49 | 1.9 |

| 16 | Viral wart | 134 | 2.9 | Telogen effluvium | 39 | 1.6 | Alopecia areata | 45 | 1.8 |

| 17 | Epidermoid cysts | 124 | 2.6 | Vitiligo | 38 | 1.6 | Chronic ulcer | 42 | 1.7 |

| 18 | Others | 117 | 2.5 | Seborrheic dermatitis | 32 | 1.3 | Viral wart | 41 | 1.6 |

| 19 | Psoriasis | 111 | 2.4 | Viral wart | 32 | 1.3 | Pemphigus and pemphigoid | 41 | 1.6 |

| 20 | Folliculitis | 60 | 1.3 | Cicatricial alopecia | 30 | 1.2 | Male or female pattern androgenetic alopecia | 39 | 1.5 |

Spearman rank R: -0.09 t=-8.52 p<0.01

Psoriasis was the tenth most frequent diagnosis in 2006 (2.5% of patients) but the sixth most frequent cause of consultations (4.4%) in 2018. This increase is likely due to greater awareness by the patients, generating greater demand for diagnosis and better adherence to treatment.42 Disease chronicity, associated with population aging, also contributes to the increased need for specialized care.43,44 The distribution of diagnoses between regions reflects the survey of capital cities in 2014, in which psoriasis was more prevalent in the south and southeast.34 Our regional differences in the rates of vitiligo, leprosy, and hidradenitis suppurativa also reproduced the findings of population-based studies in Brazil, which might be attributed to the regional ethnic composition.45-48

The differences in diagnoses regarding funding source (public, health insurance, and out of pocket payment) reflect the socioeconomic variation in patients and the need for referrals to specialists in comparing those who are covered by SUS and health insurance. Regarding socioeconomic differences, leprosy constituted 5.2% of diagnoses in SUS subjects (third most frequent) but was absent from the 20 most frequent diagnoses in health insurance and private consultations. The initial cause in diagnoses among private consultations was photoaging, with 20.5% of diagnoses, demonstrating the importance of the demand for cosmetic consultations in self-financed private practice. This pattern is reflected in the procedures that were performed, wherein the use of botulinum toxin and fillers was much more prevalent in private versus SUS and health insurance consultations. There were also more prescriptions for topical cosmeceuticals among insurance-based consultations (24.1% of patients) and for private patients (21.8%).

Before we discuss the logistic regression results, we must highlight the proposal to consider the data as a case control study-ie, considering the diagnoses for leprosy (and psoriasis and nonmelanoma cancer, analyzed separately) as “cases” and the other diagnoses as their “controls,” assuming that these groups are comparable if their selection has not been biased. To have a bias, the selection of the patient pool should alter the proportion of cases and other aspects of interest (eg, age, gender, region in Brazil). The regression results, expressed as odds ratios as a measure of association, are controlled by other items (covariables) that are included. These non-biased results can be extrapolated to the general population.

Leprosy and psoriasis were more frequent in second appointments, which is consistent with the fact that they are chronic diseases. As expected, the risk of leprosy was greater among the population that was covered by the SUS, males, non-whites, and those aged over 24 years. Unexpectedly, the northeast region of Brazil was at greater risk than those in the midwest, in contrast to published epidemiological data, although the detection rates in northeast have risen significantly.47,48 Another interpretation is that there was selection bias, because the northeast region was the least adherent in this study.

By regression analysis, there was a higher risk of psoriasis consultations in the southern region, the SUS-covered population, and those aged between 25 and 59 years, whereas for non-melanoma cancers, there was no statistically significant difference between regions, with a higher risk among those aged over 60 years and cities with fewer than 100,000 inhabitants. The latter association - a greater risk for cities - can be explained by such cities harboring populations with a history of outdoor work, such as agriculture and livestock.30,37

Finally, it is important to highlight the high proportion of patients with prescriptions for sunscreen (44%), which demonstrates a preventive approach and an attitude toward health education that are adopted by professionals.49 Diagnostic and therapeutic surgical procedures were indicated in 26.4% of visits, highlighting the prevalence of such methods in the actual clinical practice of Brazilian dermatologists.

Cosmetic/aesthetic procedures, such as the application of botulinum toxin and fillers, were more frequent among private consultations than those that were funded by health insurance or the SUS. Conversely, prescriptions for immunobiologicals were more common in SUS-based consultations, although it is unusual (1.3% of SUS patients, 0.7% of private patients, and 0.3% of health insurance-covered patients), likely reflecting their high cost, which is dependent on public funding.

The study limitations primarily concern the lack of randomization due to the spontaneous and heterogeneous adherence of dermatologists; however, all covariates (demographic, geography, and care) were considered. Another limitation was that the sample comprised only one epidemiologic week, which might have influenced the frequency of diseases with seasonal characteristics, such as psoriasis, leishmaniasis, and mycoses.50 Nevertheless, the same epidemiological week was chosen as in the 2006 study to allow comparisons to be made, constituting the main source of information on the demand for dermatological services in Latin America.

CONCLUSION

This research has allowed us to determine the epidemiological profile of outpatient demand for Brazilian dermatologists in various contexts. The results also highlight the importance of the demand for surgical and cosmetic procedures for private consultations and the significant of such diseases as nonmelanoma skin cancer, leprosy, and psoriasis to the public health.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

The SBD members who contributed to this study.

This is an original article of institutional authorship of the Brazilian Society of Dermatology (SBD). It was elaborated from a study coordinated by Dr. Hélio Amante Miot, Dr. Gerson Oliveira Penna, Dr. Andréa Machado Coelho Ramos and Dr. Maria Lúcia Fernandes Penna; under the promotion of the directors: Dr. José Antonio Sanches Júnior, Dr. Sérgio Luiz Lira Palma, Dr. Flávio Barbosa Luz, Dra. Maria Auxiliadora Jeunon Sousa e Dra. Sílvia Maria Schmidt. The main authorship belongs to all the dermatologists who contributed to the construction of knowledge about the health of the skin of the Brazilian population, to whom the SBD acknowledges.

Footnotes

Work conducted at Brazilian Society of Dermatology, Rio de Janeiro (RJ), Brazil.

Financial support: Brazilian Society of Dermatology.

Conflict of interest: None.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

Hélio Amante Miot

0000-0002-2596-9294

Statistical analysis; Approval of the final version of the manuscript; Conception and planning of the study; Elaboration and writing of the manuscript; Obtaining, analyzing and interpreting the data; Effective participation in research orientation; Intellectual participation in propaedeutic and/or therapeutic conduct of the cases studied; Critical review of the literature; Critical review of the manuscript

Gerson de Oliveira Penna

0000-0001-8967-536X

Statistical analysis; Approval of the final version of the manuscript; Conception and planning of the study; Elaboration and writing of the manuscript; Obtaining, analyzing and interpreting the data; Effective participation in research orientation; Intellectual participation in propaedeutic and/or therapeutic conduct of the cases studied; Critical review of the literature; Critical review of the manuscript

Andréa Machado Coelho Ramos

0000-0001-8891-7486

Statistical analysis; Approval of the final version of the manuscript; Conception and planning of the study; Elaboration and writing of the manuscript; Obtaining, analyzing and interpreting the data; Effective participation in research orientation; Intellectual participation in propaedeutic and/or therapeutic conduct of the cases studied; Critical review of the literature; Critical review of the manuscript

Maria Lúcia Fernandes Penna

0000-0003-0371-8037

Statistical analysis; Approval of the final version of the manuscript; Elaboration and writing of the manuscript; Critical review of the literature

Sociedade Brasileira de Dermatologia - Funding the study

Sílvia Maria Schmidt

0000-0002-3719-0309

Approval of the final version of the manuscript

Flávio Barbosa Luz

0000-0001-5454-8950

Approval of the final version of the manuscript

Maria Auxiliadora Jeunon Sousa

0000-0002-1549-1477

Approval of the final version of the manuscript

Sérgio Luiz Lira Palma

0000-0001-9056-4798

Approval of the final version of the manuscript

José Antonio Sanches Junior

0000-0002-5709-092X

Approval of the final version of the manuscript

REFERENCES

- 1.Hay RJ, Johns NE, Williams HC, Bolliger IW, Dellavalle RP, Margolis DJ, et al. The global burden of skin disease in 2010: an analysis of the prevalence and impact of skin conditions. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1527–1534. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Penha MA, Santos PM, Miot HA. Dimensioning the fear of dermatologic diseases. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:796–799. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962012000500027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dalgard FJ, Gieler U, Tomas-Aragones L, Lien L, Poot F, Jemec GBE, et al. The psychological burden of skin diseases: a cross-sectional multicenter study among dermatological out-patients in 13 European countries. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:984–991. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buendía-Eisman A, Arias-Santiago S, Molina-Leyva A, Gilaberte Y, Fernández-Crehuet P, Husein-ElAhmed H, et al. Outpatient Dermatological Diagnoses in Spain: Results From the National DIADERM Random Sampling Project. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2018;109:416–423. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2018.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lim HW, Collins SAB, Resneck Jr JS, Bolognia JL, Hodge JA, Rohrer TA, et al. The burden of skin disease in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:958–972. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boza JC, Giongo NP, Cestari TF. Vitiligo-specific instrument on quality of life - Brazilian Portuguese version. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:865–866. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20165744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cestari T, Prati C, Menegon DB, Prado Oliveira ZN, Machado MC, Dumet J, et al. Translation, cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Quality of Life Evaluation in Epidermolysis Bullosa instrument in Brazilian Portuguese. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:e94–e99. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manzoni AP, Pereira RL, Townsend RZ, Weber MB, Nagatomi AR, Cestari TF. Assessment of the quality of life of pediatric patients with the major chronic childhood skin diseases. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:361–368. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962012000300002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freitag FM, Cestari TF, Leopoldo LR, Paludo P, Boza JC. Effect of melasma on quality of life in a sample of women living in southern Brazil. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:655–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pollo CF, Miot LDB, Meneguin S, Miot HA. Factors associated with quality of life in facial melasma: a cross-sectional study. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2018;40:313–316. doi: 10.1111/ics.12464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Camargo CC, D'Elia MPB, Miot HA. Quality of life in men diagnosed with anogenital warts. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:427–429. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20175282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borges APP, Pelafsky VPC, Miot LDB, Miot HA. Quality of Life With Ingrown Toenails: A Cross-Sectional Study. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:751–753. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Penha MA, Farat JG, Miot HA, Barraviera SR. Quality of life index in autoimmune bullous dermatosis patients. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:190–194. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20153372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silvares MR, Fortes MR, Miot HA. Quality of life in chronic urticaria: a survey at a public university outpatient clinic, Botucatu (Brazil) Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992) 2011;57:577–582. doi: 10.1590/s0104-42302011000500018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Armstrong A, Jarvis S, Boehncke WH, Rajagopalan M, Fernández-Peñas P, Romiti R, et al. Patient perceptions of clear/almost clear skin in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: results of the Clear About Psoriasis worldwide survey. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018 doi: 10.1111/jdv.15065. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fried RG, Gupta MA, Gupta AK. Depression and skin disease. Dermatol Clin. 2005;23:657–664. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shuster S. Depression of self-image by skin disease. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh) 1991;156:53–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sociedade Brasileira de Dermatologia Nosologic profile of dermatologic visits in Brazil. An Bras Dermatol. 2006;81:545–554. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Curran-Everett D. Explorations in statistics: the bootstrap. Adv Physiol Educ. 2009;33:286–292. doi: 10.1152/advan.00062.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katz MH. Multivariable analysis: a practical guide for clinicians and public health researchers. 3rd ed. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andersen LK, Davis MD. The epidemiology of skin and skin-related diseases: a review of population-based studies performed by using the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88:1462–1467. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brazilian Society of Dermatology. Schmidt SM, Miot HA, Luz FB, Sousa MAJ, Palma SLL, et al. Demographics and spatial distribution of the Brazilian dermatologists. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:99–103. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20187395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmitt JV, Miot HA. Distribution of Brazilian dermatologists according to geographic location, population and HDI of municipalities: an ecological study. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:1013–1015. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20143276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miot HA, Miot LD. Time needed to schedule dermatological consultations in Brazil. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:563–569. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20132031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lugao AF, Caldas TA, Castro EL, Pereira EM, Velho PE. Dermatology relevance to graduates from the Universidade Estadual de Campinas Medical School. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:631–637. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20153740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oliveira TF, Monteguti C, Velho PE. Prevalence of skin diseases at a healthcare clinic in a small Brazilian town. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:947–949. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962010000600032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al-Hoqail IA. Epidemiological spectrum of common dermatological conditions of patients attending dermatological consultations in Al-Majmaah Region (Kingdom of Saudi Arabia) Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences. 2013;8:31–37. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilmer EN, Gustafson CJ, Ahn CS, Davis SA, Feldman SR, Huang WW. Most common dermatologic conditions encountered by dermatologists and nondermatologists. Cutis. 2014;94:285–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Handel AC, Miot LD, Miot HA. Melasma: a clinical and epidemiological review. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:771–782. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20143063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chinem VP, Miot HA. Epidemiology of basal cell carcinoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:292–305. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962011000200013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmitt JV, Masuda PY, Miot HA. Acne in women clinical patterns in different age-groups. An Bras Dermatol. 2009;84:349–354. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962009000400005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tamega Ade A, Miot LD, Bonfietti C, Gige TC, Marques ME, Miot HA. Clinical patterns and epidemiological characteristics of facial melasma in Brazilian women. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:151–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kacar SD, Ozuguz P, Polat S, Manav V, Bukulmez A, Karaca S. Epidemiology of pediatric skin diseases in the mid-western Anatolian region of Turkey. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2014;112:421–427. doi: 10.5546/aap.2014.eng.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Romiti R, Amone M, Menter A, Miot HA. Prevalence of psoriasis in Brazil - a geographical survey. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:e167–e168. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramos PM, Miot HA. Female Pattern Hair Loss: a clinical and pathophysiological review. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:529–543. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20153370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams H, Svensson A, Diepgen T, Naldi L, Coenraads PJ, Elsner P, et al. Epidemiology of skin diseases in Europe. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16:212–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmitt JV, Miot HA. Actinic keratosis: a clinical and epidemiological revision. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:425–434. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962012000300012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taylor SC. Epidemiology of skin diseases in ethnic populations. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:601–607. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(03)00075-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tamega Ade A, Miot HA, Moço NP, Silva MG, Marques ME, Miot LD. Gene and protein expression of oestrogen-ß and progesterone receptors in facial melasma and adjacent healthy skin in women. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2015;37:222–228. doi: 10.1111/ics.12186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.D'Elia MP, Brandão MC, de Andrade Ramos BR, da Silva MG, Miot LD, Dos Santos SE, et al. African ancestry is associated with facial melasma in women: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med Genet. 2017;18:17–17. doi: 10.1186/s12881-017-0378-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taylor SC. Epidemiology of skin diseases in people of color. Cutis. 2003;71:271–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferrandiz C, Carrascosa JM, Toro M. Prevalence of psoriasis in Spain in the age of biologics. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105:504–509. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miguel LMZ, Jorge MFS, Rocha B, Miot HA. Incidence of skin diseases diagnosed in a public institution: comparison between 2003 and 2014. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:423–425. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20175793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Minicucci EM, Pires RB, Vieira RA, Miot HA, Sposto MR. Assessing the impact of menopause on salivary flow and xerostomia. Aust Dent J. 2013;58:230–234. doi: 10.1111/adj.12057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ianhez M, Schmitt JV, Miot HA. Prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa in Brazil: a population survey. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:618–620. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cesar Silva de Castro C, Miot HA. Prevalence of vitiligo in Brazil-A population survey. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2018;31:448–450. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Silva CLM, Fonseca SC, Kawa H, Palmer DOQ. Spatial distribution of leprosy in Brazil: a literature review. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2017;50:439–449. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0170-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Penna ML, Grossi MA, Penna GO. Country profile: leprosy in Brazil. Lepr Rev. 2013;84:308–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schalka S, Steiner D, Ravelli FN, Steiner T, Terena AC, Marçon CR, et al. Brazilian consensus on photoprotection. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89(Suppl 1):1–74. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20143971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brito LAR, Nascimento ACM, de Marque C, Miot HA. Seasonality of the hospitalizations at a dermatologic ward (2007-2017) An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:755–758. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20187309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]