Abstract

Cutaneous metastases from internal malignant neoplasms are a rare event and a late clinical finding that is associated with disseminated disease and a poor prognosis. Skin metastases from colon tumors occur in only 4% of cases of metastatic colorectal cancer. They are most often located on the abdominal skin. We report a case of 54-year-old male patient with a cutaneous metastatic focus on the lower abdomen as the initial presenting symptom of an underlying colon cancer.

Keywords: Colonicneoplasms, Neoplasmmetastasis, Skin

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a globally important public health issue. More than 10% of cases are already metastatic tumors by the time they are diagnosed. The sites most often affected by the advanced disease are the liver, lungs and central nervous system.1 Cutaneous metastases are a rare event in the evolution of these tumors, and when present, they indicate a poor prognosis, since more than two thirds of patients die within six months after diagnosis.2

CASE REPORT

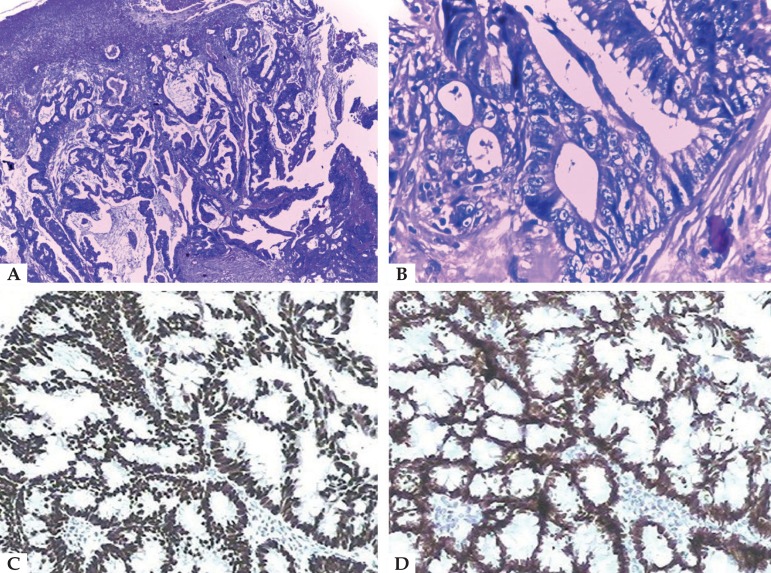

A 54-year-old man complained of a tumor, located on the abdominal wall, that had grown progressively for one year and four months. The tumor was accompanied by significant 20-kg weight loss and intestinal obstipation in the last nine months. There was no previous diagnosis of neoplasia. Under dermatological examination, we observed a vegetative tumor, with friable surface and hemorrhagic and exudative foci, measuring about 6 cm in diameter, located on the lower abdomen. In the surrounding area, we noted erythema and infiltration, simulating an inflammatory process similar to cellulitis, with retraction towards the lesion (Figure 1). A lesional biopsy was performed, and the histopathology showed a malignant neoplasm composed of well-formed ductal structures that had infiltrated the dermis, whose epithelium was composed of columnar cells of pleomorphic vesicular nuclei with more than one nucleolus and frequent atypical mitotic figures. The stroma presented a mixed inflammatory reaction of lymphocytes, neutrophils and eosinophils, fibrosis and ectatic vessels. The findings were compatible with metastatic adenocarcinoma (Figures 2A and 2B). The immunohistochemical exam was positive for villin, cytokeratin 20(CK20), CDX2 (Figure 2C) and SATB2 (Figure 2D), and negative for cytokeratin 7(CK7), confirming the colorectal origin. During the second month of investigative clinical follow-up, the patient died.

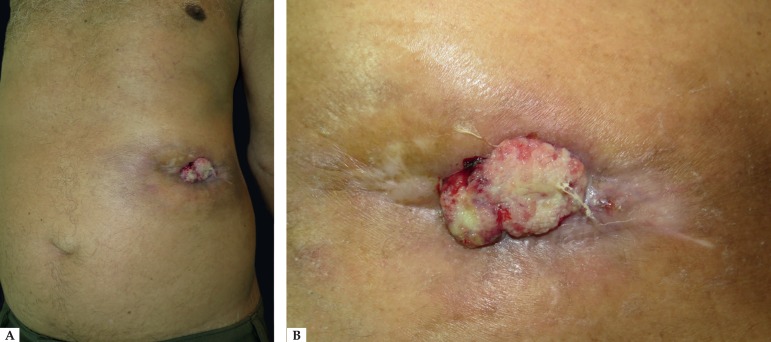

Figure 1.

A - Vegetative and ulcerated tumor, with granular and bleeding base, measuring 6cm in diameter and located on the left flank. In the surrounding area, erythema and prominent infiltration; B - Close-up of the lesion

Figure 2.

Histopathological exam. A - Metastatic adenocarcinoma - neoplasm composed of well-formed ductal structures that had infiltrated the dermis, whose epithelium was composed of columnar cells of pleomorphic vesicular nuclei, with more than one nucleolus and frequent atypical mitotic figures. The fibrovascular stroma showed erythrocyte extravasation and a mixed inflammatory reaction of lymphocytes, neutrophils and eosinophils, fibrosis and ectatic vessels (Hematoxylin & eosin, x100);

DISCUSSION

Cutaneous metastases of internal malignant neoplasms are rare, occurring in about 0.7% to 9% of all malignant diseases.3 They are generally a late manifestation of advanced-stage disease and have a poor prognosis.1-4 Neoplasms that most frequently metastasize to the skin are melanoma, breast cancer, and upper respiratory tract cancers (oral and nasal cavities and larynx).3 Most of the cases (more than 70%) present some prior history of malignant neoplasia, and the average time between the diagnosis of the primary tumor and the cutaneous metastasis is around two years.1 Rarely, a cutaneous metastasis represents the first sign of internal cancer, as in the reported case. Due to the high incidence of CRC in the general population, it is an important source of metastases to the skin. However, the tendency of CRC to cause cutaneous metastases is low, with only about 4% of affected patients presenting this clinical finding.3

Cutaneous metastases can assume diverse morphologies in these cases. Nodules and cutaneous tumors are the most frequent forms, and processes mimicking inflammation such as cellulitis are not uncommon-both patterns were observed in our patient.2,3 Ulcers, blisters, alopecia plaques and lesions that resemble herpes-zoster, epidermal cysts, neurofibromas, lymphomas, annular erythema, condylomas and elephantiasis nostras verrucosa, among other diseases, also compose the miscellany of presentations described in the literature.2,3,5

Metastases preferentially affect cutaneous sites close to the primary tumor, which, in the case of CRC, is the abdominal wall.2-4 This dissemination can be explained by the direct extension of the primary tumor to the overlying skin or through dissemination by hematogenic or lymphatic means.2 The skin is rarely affected in locations such as the pelvis, torso, thorax, upper extremities, head, neck and upper lip.6-8 Although they resemble the primary tumors, the metastases are more anaplastic and, when located in the integument, tend to spread deeply, involving the dermis and the subcutaneous cellular tissue, without continuity with the overlying epidermis.2,3

The immunohistochemical study is an important complementary tool for histopathological studies. In the case of cutaneous metastases originating from CRC, the CK7-negative/CK20-positive pattern is present in more than 70% of lesions.2 CDX2 is an expressed transcription factor in the nuclei of the epithelial cells throughout the intestine, the duodenum and the rectum. Werling RW et al. (2003) demonstrated that CDX2 was uniformly expressed in all colorectal tumors.9 In this study, in comparison with the villin, CDX2 showed greater sensitivity and comparable specificity.9 Magnusson et al. (2011) demonstrated that another marker, SATB2, is sensitive and highly specific for CRC, being positive in 85% of all cases.10 SATB2 and/or CK20 were positive in 97% of CRC cases.10

The treatment of cutaneous metastases is immediately palliative, with surgical resection reserved for solitary lesions.1,2 Radiotherapy and chemotherapy can be used for the palliation of local symptoms. Once diagnosed, the cutaneous metastases indicate a bleak prognosis: more than two thirds of patients will die within the first six months.2 Doctors that treat patients with internal carcinomas should look for skin involvement even after a long asymptomatic period, paying special attention to all nodules, ulcers that do not heal, and persistent erythema and induration. The early detection and recognition of metastatic disease on the skin can dramatically alter the treatment and prognosis in these cases.

Footnotes

Work conducted at the Dermatology Service, Universidade Federal do Pará, Belém (PA), Brazil.

Financial support: None.

Conflict of interest: None.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

Maraya de Jesus Semblano Bittencourt

0000-0002-7297-0749

Approval of the final version of the manuscript, Effective participation in research orientation, Intellectual participation in propaedeutic and/or therapeutic conduct of the cases studied, Critical review of the manuscript

Andréa Albernaz Imbiriba

0000-0003-4210-461X

Conception and planning of the study, Obtaining, analyzing and interpreting the data, Effective participation in research orientation, Critical review of the literature

Othelo Amaral Oliveira

0000-0001-5387-9555

Conception and planning of the study, Effective participation in research orientation, Intellectual participation in propaedeutic and/or therapeutic conduct of the cases studied

Josie Eiras Bisi dos Santos

0000-0001-8512-3920

Intellectual participation in propaedeutic and/or therapeutic conduct of the cases studied, Critical review of the literature

REFERENCES

- 1.Wong NS, Chang BM, Toh HC, Koo WH. Inflammatory metastatic carcinoma of the colon: a case report and review of the literature. Tumori. 2004;90:253–255. doi: 10.1177/030089160409000218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saeed S, Keehn CA, Morgan MB. Cutaneous metastasis: a clinical, pathological, and immunohistochemical appraisal. J CutanPathol. 2004;31:419–430. doi: 10.1111/j.0303-6987.2004.00207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am AcadDermatol. 1993;29:228–236. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(93)70173-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nesseris I, Tsamakis C, Gregoriou S, Ditsos I, Christofidou E, Rigopoulos D. Cutaneous metastasis of colon adenocarcinoma: case report and review of the literature. AnBrasDermatol. 2013;88:56–58. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20132441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ocampo-Candiani J, Castrejón-Pérez AD, Ayala-Cortés AS, Martínez-Cabriales SA, Garza-Rodríguez V. CutaneousColonMetastasesMimickingElefantiasis Verrucosa Nostra. Am J MedSci. 2015;350:517–518. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0000000000000595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Góes HF, Lima C dos S, Souza MB, Estrella RR, Faria MA, Rochael MC. Single cutaneous metastasis of colon adenocarcinoma - Case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:517–519. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20164122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Attili VS, Rama Chandra C, Dadhich HK, Sahoo TP, Anupama G, Bapsy PP. Unusual metastasis in colorectal cancer. Indian J Cancer. 2006;43:93–95. doi: 10.4103/0019-509x.25891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moonda A, Fatteh S. Metastatic colorectal carcinoma: an unusual presentation. J CutanPathol. 2009;36:64–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2008.01007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Werling RW, Yaziji H, Bacchi CE, Gown AM. CDX2, a highly sensitive and specific marker of adenocarcinomas of intestinal origin: an immunohistochemical survey of 476 primary and metastatic carcinomas. Am J SurgPathol. 2003;27:303–310. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200303000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Magnusson K, de Wit M, Brennan DJ, Johnson LB, McGee SF, Lundberg E, et al. SATB2 in combination with cytokeratin 20 identifies over 95% of all colorectal carcinomas. Am J SurgPathol. 2011;35:937–948. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31821c3dae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]