Abstract

We assessed how community education efforts influenced pregnant women’s Zika prevention behaviors during the 2016 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention–Puerto Rico Department of Health Zika virus response. Efforts included Zika virus training, distribution of Zika prevention kits, a mass media campaign, and free home mosquito spraying. We used telephone interview data from pregnant women participating in Puerto Rico’s Women, Infants, and Children Program to test associations between program participation and Zika prevention behaviors. Behavior percentages ranged from 4% (wearing long-sleeved shirt) to 90% (removing standing water). Appropriate mosquito repellent use (28%) and condom use (44%) were common. Receiving a Zika prevention kit was significantly associated with larvicide application (odds ratio [OR] 8.0) and bed net use (OR 3.1), suggesting the kit's importance for lesser-known behaviors. Offer of free residential spraying was associated with spraying home for mosquitoes (OR 13.1), indicating that women supported home spraying when barriers were removed.

Keywords: Zika virus, health behavior, program effectiveness, maternal health, mosquito bed nets, interpersonal communication, risk perception, viruses, pregnancy, Puerto Rico

In early 2016, in response to the rising number of Zika virus infections in Puerto Rico and the devastating effects of Zika infection during pregnancy (1), the Puerto Rico Department of Health (PRDOH) activated its emergency operations center, with support from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2). Because there is currently no Zika virus vaccine and no known measures can prevent prenatal mother-to-child transmission (3), personal protection measures and home vector control are the only feasible protections for most pregnant women. To maximize these self-protection behaviors, the response introduced 4 different community Zika prevention behavior promotion interventions. Health behavior interventions can change behavior by addressing behavioral barriers, by creating or enhancing incentives, and by increasing persons’ capabilities and opportunities to perform the behavior (4).

Interventions

PRDOH Women, Infants, and Children Program Zika Orientation

During the tracking period, all newly enrolled pregnant women at 1 of the island’s 92 Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) clinics were given a 20–30-minute presentation on Zika virus infection and prevention. Orientation (individually or in small groups) was provided by the nutrition educator or, during the peak of the epidemic, by a Zika educator provided by CDC. The primary advantages of this counseling approach are interpersonal communication (including answering questions) and how easily it can be integrated into existing trusted programs, such as WIC prenatal visits (5,6).

Zika Prevention Kit Distribution

The Zika prevention kit (ZPK) was a tote bag containing insect repellent, condoms, a mosquito bed net, larvicide, and printed Zika education materials. Approximately 26,000 ZPKs were distributed in Puerto Rico (CDC–Puerto Rico Department of Health, unpub. data, April 26, 2017). Whenever possible, the ZPK was given to the pregnant woman at the same time as the WIC Zika orientation. Prevention kits enable healthy behavior by putting needed items in persons’ hands but also by providing a visual reminder of the recommended behavior. Similar home infection prevention kits were used during the Zika response in the US Virgin Islands (7) and during the Ebola epidemic in West Africa (8–10) to provide home caregivers with tools to prevent virus transmission. Only HIV infection prevention kits have been evaluated to date; these preliminary evaluations indicate kit popularity and suggest supportive effects (11,12).

Detén el Zika Campaign

The Detén el Zika (“This Is How We Stop Zika”) campaign disseminated strategically designed Zika prevention messages through television, radio, print, and social media channels (13). The television advertisement included a montage showing couples or pregnant women and their families performing the following behaviors: using repellent, using condoms, using bed nets, removing standing water, and installing screens. Mass media campaigns have the advantage of reaching multiple audiences (including partners, families, and pregnant women not enrolled in WIC) with repeating messages that appeal cognitively and emotionally by showing relatable images of women taking preventive steps and by showing a healthy baby (14).

Offer of Free Residential Mosquito Spraying Services

When pregnant women attended their WIC appointments, they were also offered a free residential mosquito spraying service. Upon consent, WIC provided women’s contact information to a contracted professional spraying service. Across the island, ≈3,400 homes were sprayed through this program. For this analysis, this intervention is defined as the offer of free residential spraying services, meaning that women who report being offered the free service are classified as exposed to the intervention, regardless of whether they chose to use the service. In this way, we can determine whether having free residential spraying services available affected the overall frequency of spraying the home (or yard) for mosquitoes.

Although we might intuit that making residential spraying free would increase use, the literature contains inconsistent evidence about whether removing cost barriers increases vector control behavior (15–17). This offer of free residential mosquito spraying was discontinued in August 2016 after a CDC evaluation found that mosquito populations in and around sprayed homes had not changed, probably as a result of movement of mosquitoes from nearby homes (18).

Intervention Implementation Monitoring

As these interventions were being implemented, the response behavioral science team conducted monthly telephone interviews of a random sample of 300 pregnant women participating in WIC to provide feedback to the response leadership about intervention exposure and women’s Zika prevention behavior. A subset of 150 respondents were asked about their performance of the following 10 CDC-recommended behaviors: using mosquito repellent, using condoms, abstaining from sex, wearing long-sleeved shirts, wearing long pants, sleeping under a bed net, removing or covering standing water, applying larvicide (in water that cannot be removed), putting screens on windows and doors, and spraying home and yard for mosquitoes. This assessment continued until June 2017, when PRDOH declared the Zika epidemic over (19). During 2016–2017, a total of 9 monthly (in 2017, bimonthly) interview rounds were conducted. Our analysis addresses the following: 1) the proportion of pregnant respondents reached by the 4 interventions and the factors associated with exposure; 2) the Zika prevention behaviors that were most widely practiced and that were most strongly associated with exposure to interventions; and 3) additional factors associated with Zika prevention behavior that might provide insight into how the interventions influenced behavior.

Methods

Interview Population and Sampling

Each month during July–December 2016 and every 2 months during February–June 2017, a random sample of 950 pregnant women >18 years of age (317 women per pregnancy trimester) was drawn from the WIC enrollment database of 10,000–12,000 women currently enrolled (and not previously contacted) for interviews. Vital statistics data indicate that 87% of women giving birth in Puerto Rico in 2016 were enrolled in WIC (Table 1). The calling list was divided among interviewers so that some began with first trimester women, some with second, and some with third. As part of the Zika response, these interviews were determined to be nonresearch public health practice and were approved by the US Office of Management and Budget (control no. 0920–1196). Before asking women for their verbal agreement to participate, interviewers explained the purpose of the data collection, the fact that their participation and all responses would be kept confidential, and that they could discontinue the interview any time without any penalty. The 3 groups of callers continued until 300 total interviews were completed. The interview had 2 parts, administered 2 weeks apart. Those women who consented to complete part 2 were called in the same order as for part 1 until 150 interviews were completed.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of all women giving birth in 2016 and interview participants, Puerto Rico, July 2016–June 2017*.

| Characteristic | Sample size, no. (%) | Women who gave birth in 2016, no. (%)† |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| >18 y of age | All ages | ||

| Total sample |

1,329 (100) |

27,230 (100) |

28,257 (100) |

| Age group, y | |||

| <18‡ | 0 | 0 | 1,027 (4) |

| 18–22 | 353 (27) | 7,963 (29) | 7,963 (28) |

| 23–25 | 324 (24) | 5,436 (20) | 5,436 (19) |

| 26–29 | 319 (24) | 5,884 (22) | 5,884 (21) |

| >30 | 333 (25) | 7,947 (29) | 7,947 (28) |

| Total sample |

1,329 (100) |

27,230 (100) |

28,257 (100) |

| Educational attainment | |||

| Some high school or less | 24 (3) | 427 (2) | 579 (2) |

| Attended or completed 12th grade | 285 (31) | 9,105 (34)§ | 9,958§ (35) |

| Attended or completed university | 545 (60) | 15,648 (58) | 15,670 (55) |

| Attended or completed graduate program | 55 (6) | 2031 (8) | 2,031 (7) |

| Total sample |

909¶ (100) |

27,230 (100) |

28,257 (100) |

| Participation in WIC program# |

1,329 (100) |

23,679 (87) |

24,671 (87) |

| Geographic region of Puerto Rico | |||

| Metropolitan San Juan | 203 (15) | 2,864 (11) | 2,955 (10) |

| Metropolitan Bayamon | 182 (14) | 1,556 (6) | 1,597 (6) |

| Nonmetropolitan regions | 941 (71) | 22,810 (83) | 23,705 (84) |

| Total sample | 1,327 (100) | 27,230 (100) | 28,257 (100) |

*NCHS, National Center for Health Statistics (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention); WIC, Women, Infants, and Children Program (US Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service). †Source: NCHS’s US Territories, 2016 natality public use file (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data_access/vitalstatsonline.htm). ‡Because women had to be >18 years of age to participate, the <18 age category is empty for the WIC sample. §In the NCHS data, this group includes 9th–12th grade, not just 12th grade. ¶The educational attainment data in the WIC dataset (n = 909) were incomplete. The data here represent 68% of the total sample of 1,329. #Source: WIC (https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/women-infants-and-children-wic).

Data Collection

The interview consisted of questions about Zika knowledge, attitudes, sources of information, exposure to prevention interventions, and Zika prevention behaviors. Many of the questions involved binary (e.g., yes or no) or scaled (e.g., never, rarely, sometimes, frequently, or often) responses. Others were questions in which the interviewer did not provide response options to the participant but coded the response according to a checklist. Although Zika infection status was not an interview question, if a participant disclosed that she was Zika positive, the interview was excluded from the dataset. This exclusion was made because Zika virus infection confers immunity and therefore an already positive woman would have no reason to take prevention steps.

Definition of Intervention Exposure

Respondents were asked if they had received the WIC Zika orientation, the ZPK, or the offer of free home spraying. They were also asked if they had seen communications from the Detén el Zika campaign. Any woman answering affirmatively to any of these questions was defined as exposed to the corresponding intervention.

Data Analysis

Calculation of Zika Prevention Behavior Variables

Because the original interview instrument included multiple questions about each Zika prevention behavior without any clear formula for integrating question responses into a single variable (1 per behavior), analysts had to create such a formula. For example, some questions asked whether a woman performed the behavior any time during pregnancy (or during the previous day or week) (yes or no), whereas others used ordinal frequency scales (e.g., never, sometimes, or always). In addition, a Zika prevention behavior could be reported in response to the question, “What actions have you taken to protect yourself from being infected by the Zika virus?”

To describe women’s Zika prevention behavior as completely as possible, analysts created behavior variables that incorporated 2, 3, or more questions. We prioritized time-bound, behavior-specific questions, such as, “How often did you use mosquito repellent in the past week?” (never, sometimes, or always), over a more general question such as, “What actions have you taken to protect yourself from being infected with the Zika virus?” Among the behavior-specific questions, those questions with multilevel response options were prioritized over yes or no or dichotomous response questions, given that the greater number of response options yielded more information. Zika prevention behavior variables were then created with ordinal scales, combining the most detailed behavior-specific question available for the behavior with other questions that might serve to increase the number of levels of Zika prevention behavior. Once preliminary scales were created, frequencies and plots were reviewed by behavioral scientists and epidemiologists involved with the Zika response to achieve a consensus on the final composition. We have compiled a list of all candidate questions and final variables (Technical Appendix).

Statistical Methods

Analysts calculated frequencies of intervention exposure by interview month and demographic characteristics. In addition, because the interventions sought to increase Zika prevention behavior by increasing a woman’s concern about Zika, her confidence in her ability to protect herself, and involvement of partners and families in Zika prevention, variables representing these constructs were tested for associations with intervention exposure and Zika prevention behaviors. All analyses were conducted with SPSS 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Analysists used logistic regression modeling to estimate odds ratios (ORs) for the likelihood of performing recommended Zika prevention behaviors by exposure to 1 of the Zika prevention interventions while controlling for the effects of age, education, pregnancy trimester, poverty, calendar month of interview, and exposure to other interventions. For these models, Zika prevention behavior variable responses were collapsed into dichotomous (yes or no) variables, indicating whether a respondent had performed the ideal behavior (e.g., always uses a condom) or not. In the case of mosquito repellent use, the 2 top levels, which both include the response always, were combined to make the top level.

Because the WIC orientation reached nearly all respondents, the naturally occurring control group of unexposed women was very small, causing concerns about small cell size in models with many covariates (20). Conversely, a small exposure group was a concern with the offer of free residential mosquito spraying. Therefore, these 2 interventions were modeled separately from ZPK distribution and Detén el Zika, which were modeled together. In addition, sparsity concerns led us to consolidate the calendar month of interview variable into 1 representing 3-month intervals.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Our sample encompassed 1,329 pregnant WIC participants interviewed during July 2016–June 2017 (Table 1). Among eligible women (i.e., >18 years of age, pregnant, and not Zika positive), the response rate was 79%. Age and educational attainment distributions of the sample were similar to the general population of women giving birth in Puerto Rico in 2016 (21), whereas urban residence is somewhat higher.

Women’s Exposure to 4 Zika Prevention Interventions

Women reported exposure to the 4 interventions as follows: WIC Zika orientation (93%), ZPK distribution (75%), Detén el Zika campaign (51%), and offer of free residential mosquito spraying (68% for the months it was running and 34% over the entire period). Pregnancy trimester was statistically significant for association with exposure to all 4 interventions, whereas calendar month of interview was significantly associated with 3 interventions (Table 2). No significant associations were observed in terms of age, education, poverty, or rurality.

Table 2. Respondents exposure to 4 Zika prevention interventions, by demographic characteristics and calendar month, Puerto Rico, July 2016–June 2017*.

| Characteristic | Sample | Received WIC Zika orientation |

Received ZPK |

Exposed to Detén el Zika campaign |

Offered free home spraying |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |||||

| Pregnancy trimester at interview | ||||||||||||

| 1st | 26.8 | 8.4 | 91.6 | 32.9 | 67.1 | 52.2 | 47.8 | 68.1 | 31.9 | |||

| 2nd | 48.6 | 8.2 | 91.8 | 24.6 | 75.4 | 45.9 | 54.1 | 71.7 | 28.3 | |||

| 3rd | 24.6 | 3.7 | 96.3 | 16.9 | 83.1 | 53.4 | 46.6 | 52.8 | 47.2 | |||

| Total no. | 1,329 | 95 | 1,230 | 324 | 976 | 600 | 616 | 873 | 448 | |||

| p value |

|

0.019

|

|

0.000

|

|

0.052

|

|

0.000

|

||||

| Calendar month of interview | ||||||||||||

| Jul 2016 | 11.2 | 4.8 | 95.2 | 4.8 | 95.2 | 62.9 | 37.1 | 29.7 | 70.3 | |||

| Aug 2016 | 11.1 | 8.2 | 91.8 | 23.8 | 76.2 | 59.2 | 40.8 | 29.3 | 70.7 | |||

| Sep 2016 | 10.1 | 6.0 | 94.0 | 31.3 | 68.7 | 44.4 | 55.6 | 34.6 | 65.4 | |||

| Oct 2016 | 11.3 | 10.7 | 89.3 | 41.3 | 58.7 | 31.6 | 68.4 | 65.8 | 34.2 | |||

| Nov 2016 | 11.3 | 8.0 | 92.0 | 31.3 | 68.7 | 35.0 | 65.0 | 70.1 | 29.9 | |||

| Dec 2016 | 11.3 | 4.0 | 96.0 | 30.0 | 70.0 | 36.1 | 63.9 | 72.7 | 27.3 | |||

| Feb 2017 | 11.3 | 6.7 | 93.3 | 20.7 | 79.3 | 55.2 | 44.8 | 97.3 | 2.7 | |||

| Apr 2017 | 11.3 | 5.3 | 94.7 | 16.0 | 84.0 | 68.1 | 31.9 | 94.7 | 5.3 | |||

| Jun 2017 | 11.2 | 10.7 | 89.3 | 22.1 | 77.9 | 52.9 | 47.1 | 96.6 | 3.5 | |||

| Total no. | 1,329 | 203 | 1,230 | 324 | 976 | 600 | 616 | 873 | 418 | |||

| p value |

|

0.225 |

|

0.000

|

|

0.000

|

|

0.000

|

||||

| Age group, y | ||||||||||||

| 18–22 | 26.6 | 6.8 | 93.2 | 22.3 | 77.7 | 51.0 | 49.0 | 66.2 | 33.8 | |||

| 23–25 | 24.4 | 7.4 | 92.6 | 23.5 | 76.5 | 52.1 | 47.9 | 68.5 | 68.5 | |||

| 26–29 | 24.0 | 6.9 | 93.1 | 27.0 | 73.0 | 44.1 | 55.9 | 64.9 | 35.1 | |||

| >30 | 25.1 | 7.5 | 92.5 | 27.2 | 72.8 | 49.8 | 50.2 | 64.8 | 35.2 | |||

| Total no. | 1,329 | 95 | 1,230 | 324 | 976 | 600 | 616 | 873 | 448 | |||

| p value |

|

0.981 |

|

0.356 |

|

0.217 |

|

0.723 |

||||

| Educational attainment | ||||||||||||

| Some high school or less | 2.6 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 21.7 | 78.3 | 54.5 | 45.5 | 66.7 | 33.3 | |||

| Attended or completed 12th grade | 31.4 | 7.4 | 92.6 | 22.3 | 77.7 | 49.4 | 50.6 | 66.1 | 33.9 | |||

| Attended or completed university | 60.0 | 6.1 | 93.9 | 23.6 | 76.4 | 49.9 | 50.1 | 62.2 | 37.8 | |||

| Attended or completed graduate program | 6.1 | 7.3 | 92.7 | 25.6 | 74.1 | 36.2 | 63.8 | 58.2 | 41.8 | |||

| Total no. | 909 | 58 | 848 | 207 | 681 | 404 | 419 | 572 | 332 | |||

| p value |

|

0.512 |

|

0.934 |

|

0.315 |

|

0.579 |

||||

| Population in poverty in Zip code, % quartiles† | ||||||||||||

| >55 below poverty | 25.0 | 5.1 | 94.9 | 22.8 | 77.2 | 49.5 | 50.5 | 65.2 | 34.8 | |||

| 49–54 below poverty | 25.3 | 7.9 | 92.1 | 25.6 | 74.4 | 43.7 | 56.3 | 67.5 | 32.5 | |||

| 43–48 below poverty | 25.1 | 6.7 | 93.3 | 23.1 | 76.9 | 51.6 | 48.4 | 64.2 | 35.8 | |||

| <43 below poverty | 24.5 | 8.8 | 91.2 | 29.2 | 70.8 | 53.1 | 46.9 | 68.1 | 31.9 | |||

| Total no. | 1,255 | 89 | 1,163 | 309 | 918 | 566 | 579 | 826 | 421 | |||

| p value |

|

0.305 |

|

0.234 |

|

0.125 |

|

0.700 |

||||

| Municipality population | ||||||||||||

| >200,000 | 63.5 | 6.1 | 93.9 | 23.1 | 76.9 | 48.6 | 51.4 | 66.0 | 34.0 | |||

| >100,00–200,000 | 9.9 | 10.6 | 89.4 | 31.3 | 68.7 | 50.4 | 49.6 | 61.8 | 38.2 | |||

| >50,000–100,000 | 12.6 | 7.7 | 92.3 | 27.9 | 72.1 | 46.8 | 53.2 | 63.3 | 36.7 | |||

| <50,000 | 14.0 | 8.8 | 91.2 | 26.3 | 73.7 | 56.1 | 43.9 | 72.5 | 27.5 | |||

| Total no. | 1,326 | 91 | 1,184 | 313 | 937 | 578 | 589 | 839 | 431 | |||

| p value | 0.213 | 0.163 | 0.328 | 0.187 | ||||||||

*All data are percentages unless otherwise indicated. Statistically significant differences (p<0.05 by χ2 test) are shown in boldface. WIC, Women, Infants, and Children Program (US Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service); ZPK, Zika prevention kit. †Source: US Census Bureau American Community Survey, 2016. American Community Survey 5-year estimates, Table S1701 (generated by G.B.E. using American Fact Finder, 2018 Feb 24).

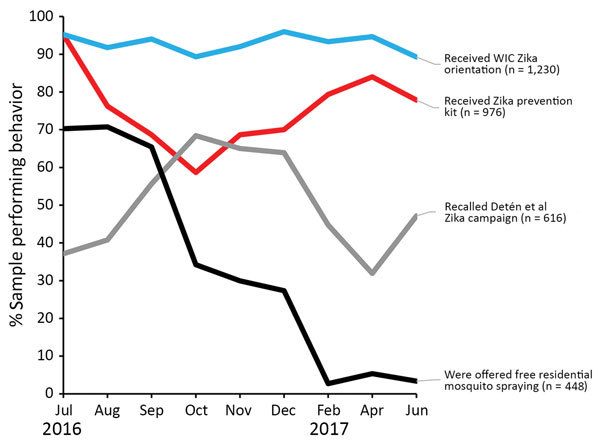

Graphed by calendar month of interview (Figure 1), exposure to the WIC Zika orientation remained consistently high (89%–96%). ZPK distribution began high (95%), dropped in October, then rebounded. Detén el Zika campaign exposure began much lower (37%), then steadily increased through October (68%), dropped off, and rose again in 2017. Exposure to the offer of free residential mosquito spraying started at 70% in July 2016, then dropped precipitously after September.

Figure 1.

Percentage of pregnant women reporting exposure to 4 Zika prevention interventions, by interview month, Puerto Rico, 2016–2017. August 12, 2016: President declares Zika in Puerto Rico a “public health emergency” (https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-usa/u-s-declares-a-zika-public-health-emergency-in-puerto-rico-idUSKCN10N2KA). September 30, 2016: Free residential spraying discontinued. Women who report the offer through December are referring to receiving the offer before September. October 28, 2016: First baby born with microcephaly in Puerto Rico (https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/29/health/zika-microcephaly-puerto-rico.html). June 5, 2017: Zika epidemic declared over by Puerto Rico Department of Health (https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20170605006235/en/Puerto-Rico-Department-Health-Declared-2016-Zika). WIC, Women, Infants, and Children Program (US Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service).

Intervention exposure was more often significantly associated with family or interpersonal communication variables than with individual risk variables (Table 3). The same pattern was observed for associations with Zika prevention behaviors (data not shown): “frequency of talking to family and friends about Zika” was significantly associated with 10 behaviors and “aware of Zika prevention actions of family” with 5 behaviors, whereas all 3 individual risk perception–related variables were associated with <3 behaviors.

Table 3. Associations between Zika prevention intervention exposure and interpersonal communications about Zika and personal risk perceptions, Puerto Rico, July 2016–June 2017*.

| Variable | Sample | Received WIC Zika orientation |

Received ZPK |

Exposed to Detén el Zika campaign |

Offered free home spraying |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |||||

| Family and interpersonal communication | ||||||||||||

| Frequency of talking to family and friends about Zika | ||||||||||||

| Not at all | 10.7 | 8.4 | 10.8 | 9.9 | 11.1 | 14.5 | 7.3 | 12.7 | 6.7 | |||

| Only once or twice | 16.2 | 21.1 | 15.9 | 16.7 | 16.1 | 17.7 | 15.3 | 17.4 | 13.6 | |||

| Sometimes | 32.7 | 45.3 | 31.8 | 34.9 | 32.3 | 33.0 | 32.5 | 33.3 | 31.5 | |||

| Often | 22.0 | 16.8 | 22.4 | 18.5 | 22.7 | 19.2 | 23.5 | 20.3 | 25.2 | |||

| Every day | 18.4 | 8.4 | 19.2 | 20.1 | 17.8 | 15.7 | 21.4 | 16.3 | 23.0 | |||

| Total no. | 1,329 | 79 | 1,230 | 600 | 616 | 324 | 976 | 873 | 448 | |||

| p value | 0.009 | 0.472 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||||||

| Aware of Zika prevention actions of family | ||||||||||||

| No | 38.3 | 38.8 | 38.2 | 38.2 | 38.4 | 46.0 | 31.0 | 41.4 | 30.9 | |||

| Yes | 61.7 | 61.2 | 61.8 | 61.8 | 61.6 | 54.0 | 69.0 | 58.6 | 69.1 | |||

| Total no. | 1,168 | 85 | 1,081 | 511 | 561 | 314 | 850 | 818 | 343 | |||

| p value |

|

0.910 |

|

0.966 |

|

0.000

|

|

0.001

|

||||

| Individual risk perception | ||||||||||||

| How concerned women feel about Zika | ||||||||||||

| Not at all concerned | 8.2 | 7.4 | 8.3 | 5.6 | 9.0 | 8.8 | 7.8 | 8.9 | 6.7 | |||

| Slightly concerned | 16.4 | 13.7 | 16.7 | 14.8 | 17.1 | 17.9 | 15.6 | 17.7 | 13.8 | |||

| Somewhat concerned | 21.1 | 20.0 | 21.2 | 20.7 | 21.1 | 21.7 | 21.1 | 21.6 | 20.3 | |||

| Moderately concerned | 27.3 | 33.7 | 26.6 | 30.2 | 26.4 | 27.4 | 26.8 | 27.5 | 26.8 | |||

| Extremely concerned | 27.0 | 25.3 | 27.3 | 28.7 | 26.4 | 24.2 | 28.7 | 24.3 | 32.4 | |||

| Total no. | 1,328 | 95 | 1,229 | 599 | 616 | 324 | 975 | 872 | 448 | |||

| p value | 0.665 | 0.182 | 0.435 | 0.019 | ||||||||

| How likely women feel they will become infected with Zika | ||||||||||||

| Extremely unlikely | 10.0 | 9.7 | 10.0 | 8.1 | 10.8 | 10.2 | 9.9 | 12.0 | 5.9 | |||

| Unlikely | 37.4 | 36.6 | 37.4 | 37.4 | 37.4 | 36.6 | 38.0 | 36.8 | 38.4 | |||

| Neither likely nor unlikely | 30.6 | 32.3 | 30.5 | 31.5 | 30.2 | 30.3 | 31.4 | 31.0 | 30.2 | |||

| Likely | 19.4 | 19.4 | 19.4 | 20.9 | 18.8 | 19.3 | 18.8 | 18.0 | 22.1 | |||

| Extremely likely | 2.7 | 2.2 | 2.7 | 2.2 | 2.8 | 3.6 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 3.4 | |||

| Total no. | 1,306 | 93 | 1,209 | 587 | 606 | 321 | 957 | 855 | 443 | |||

| p value | 0.994 | 0.607 | 0.549 | 0.003 | ||||||||

| Confidence in ability to protect self and baby from Zika | ||||||||||||

| Not confident at all | 1.1 | 2.1 | 1.1 | 1.9 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 0.9 | |||

| Somewhat unconfident | 9.9 | 16.0 | 9.4 | 10.3 | 9.6 | 10.1 | 9.3 | 10.0 | 9.5 | |||

| Not confident or unconfident | 22.3 | 27.7 | 21.8 | 20.6 | 22.3 | 24.7 | 20.2 | 21.1 | 24.8 | |||

| Confident | 49.5 | 45.7 | 49.9 | 48.9 | 50.1 | 49.5 | 49.8 | 50.7 | 47.1 | |||

| Very confident | 17.2 | 8.5 | 17.9 | 18.4 | 17.1 | 14.6 | 19.3 | 16.8 | 17.8 | |||

| Total no. | 1,319 | 94 | 1,221 | 596 | 610 | 321 | 969 | 867 | 444 | |||

| p value | 0.030 | 0.634 | 0.139 | 0.530 | ||||||||

*All data indicate percentages unless otherwise indicated. Statistically significant differences (p<0.05 by χ2 test) are shown in boldface. WIC, Women, Infants, and Children Program (US Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service); ZPK, Zika prevention kit.

Pregnant Women’s Zika Personal Protection Behaviors

Frequencies of recommended personal protection behaviors (i.e., the top level on the ordinal scale) ranged from 4% (wearing long-sleeved shirt) to 44% (condom use) (Table 4). Although just over half of women reported using repellent always, fewer (28%) reported the top category, “used always and reported reapplying it.” Among the interventions, exposure to the WIC Zika orientation showed the greatest exposed versus not exposed frequency differences for the top behavior levels (Tables 4, 5).

Table 4. Zika personal protection behaviors among pregnant women, by exposure to 4 interventions, Puerto Rico, July 2016–June 2017*.

| Behavior | Entire sample | Received WIC Zika orientation |

Received ZPK |

Exposed to Detén el Zika campaign |

Offered free home spraying |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |||||

| Mosquito repellent use | ||||||||||||

| Always, reported reapplying | 28.3 | 29.1 | 18.9 | 29.7 | 24.5 | 31.2 | 25 | 32.6 | 26.1 | |||

| Always, did not report reapplying | 23.9 | 23.5 | 28.4 | 24.1 | 23.5 | 27.6 | 21.5 | 23.9 | 23.9 | |||

| Usually or most of the time | 25.9 | 26.4 | 21.1 | 25.9 | 26 | 23.1 | 28.4 | 23.2 | 27.1 | |||

| Sometimes | 13.0 | 12.8 | 14.7 | 12.2 | 15.2 | 11.7 | 14.5 | 13.2 | 13.1 | |||

| Rarely or seldom | 4.6 | 4.4 | 7.4 | 4.7 | 4.0 | 3.9 | 4.7 | 4.0 | 4.9 | |||

| Never | 4.2 | 3.8 | 9.5 | 3.4 | 6.8 | 2.6 | 5.8 | 3.1 | 4.8 | |||

| Total no. | 1,328 | 1,229 | 95 | 976 | 323 | 614 | 597 | 448 | 873 | |||

| p value |

|

0.018

|

|

0.016

|

|

<0.001

|

|

0.012

|

||||

| Condom use† | ||||||||||||

| Always | 44.1 | 45.3 | 31.6 | 45.1 | 42.6 | 44.2 | 26.3 | 42.5 | 44.8 | |||

| Sometimes | 29.3 | 29.5 | 24.1 | 30.6 | 25.8 | 28.7 | 26.3 | 28.3 | 29.9 | |||

| Never | 26.6 | 25.2 | 44.3 | 24.3 | 31.6 | 27.2 | 47.4 | 29.2 | 25.3 | |||

| Total no. | 1,047 | 964 | 79 | 768 | 256 | 491 | 464 | 353 | 689 | |||

| p value |

|

0.001

|

|

0.130 |

|

0.001

|

|

0.266 |

||||

| Bed net use | ||||||||||||

| Slept under bed net yesterday | 14.8 | 15.4 | 7.4 | 17.7 | 6.8 | 16.1 | 13.8 | 13.8 | 15.3 | |||

| Did not use yesterday, reports use generally | 4.9 | 5.2 | 1.1 | 5.7 | 2.5 | 4.2 | 4.7 | 3.1 | 5.8 | |||

| Did not use yesterday, does not report use generally | 80.3 | 79.4 | 91.6 | 76.5 | 90.7 | 79.7 | 81.5 | 83 | 78.8 | |||

| Total no. | 1,329 | 1,230 | 95 | 976 | 324 | 616 | 600 | 448 | 873 | |||

| p value |

|

0.005

|

|

|

<0.001

|

|

0.390 |

|

0.094 |

|||

| Wearing long pants | ||||||||||||

| Wearing now, every day, all day | 21.3 | 21.4 | 21.1 | 20.6 | 23.5 | 21.2 | 20.8 | 20.6 | 21.5 | |||

| Wearing now, every day, part of day | 19.2 | 19.5 | 15.8 | 18.7 | 21.0 | 20.4 | 18.3 | 19.7 | 19.0 | |||

| Wearing now, does not wear every day | 20.0 | 20 | 21.1 | 20.0 | 19.4 | 20.5 | 20 | 17.7 | 21.3 | |||

| Not wearing long pants now | 39.4 | 39.1 | 42.1 | 40.7 | 36.1 | 40.8 | 37.9 | 41.9 | 38.1 | |||

| Total no. | 1,327 | 1,228 | 95 | 974 | 324 | 614 | 600 | 446 | 873 | |||

| p value |

|

0.549 |

|

0.098 |

|

0.378 |

|

0.402 |

||||

| Sexual abstinence | ||||||||||||

| Had no sex during pregnancy | 20.2 | 20.7 | 15.8 | 20.3 | 19.9 | 31.2 | 25.0 | 20.6 | 19.9 | |||

| Had sex during pregnancy | 79.8 | 79.3 | 84.2 | 79.7 | 80.1 | 80.6 | 78.2 | 79.4 | 80.1 | |||

| Total no. | 1,324 | 1,225 | 95 | 973 | 322 | 614 | 597 | 447 | 869 | |||

| p value |

|

0.256 |

|

0.855 |

|

0.303 |

|

0.773 |

||||

| Wearing long-sleeved shirt | ||||||||||||

| Wearing now, every day, all day | 3.9 | 3.8 | 5.3 | 3.7 | 4.7 | 77.7 | 79.3 | 4.0 | 3.8 | |||

| Wearing now, every day, part of day | 6.7 | 6.7 | 7.4 | 7.2 | 5.6 | 6.4 | 7.2 | 6.9 | 6.7 | |||

| Wearing now, does not wear every day | 10.6 | 10.8 | 7.4 | 9.9 | 13.7 | 11.1 | 10.4 | 8.9 | 11.5 | |||

| Not wearing long sleeves now | 78.7 | 78.6 | 79.8 | 79.3 | 79.3 | 79.3 | 83.5 | 80.1 | 78 | |||

| Total no. | 1,325 | 1,227 | 94 | 974 | 322 | 614 | 598 | 448 | 869 | |||

| p value | 0.915 | 0.289 | 0.464 | 0.457 | ||||||||

*All data indicate percentages unless otherwise indicated. Statistically significant differences (p<0.05 by Mann-Whitney U nonparametric test) are shown in bold. WIC, Women, Infants, and Children Program (US Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service); ZPK, Zika prevention kit. †Among those reporting having had sex during pregnancy.

Table 5. Zika home protection behaviors among pregnant women, by exposure to 4 interventions, Puerto Rico, July 2016–June 2017*.

| Behavior | Samples, % (no.) | Received WIC Zika orientation |

Received ZPK |

Exposed to Detén el Zika campaign |

Offered free home spraying |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |||||

| Removing (or covering) standing water* | ||||||||||||

| Removed standing water in past week | 90.3 (531) | 90.5 | 87.2 | 91.8 | 85.5 | 93.9 | 85.6 | 91.3 | 90.2 | |||

| Has not in past week; reports action generally | 1.2 (7) | 1.1 | 2.6 | 0.9 | 2.2 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.9 | 0.8 | |||

| Has not in past week; does report action generally | 8.5 (50) | 8.4 | 10.3 | 7.3 | 12.3 | 4.7 | 13.2 | 6.8 | 9.0 | |||

| Total no. | 588 | 546 | 39 | 438 | 138 | 297 | 243 | 377 | 206 | |||

| p value |

|

0.516 |

|

0.032

|

|

0.001

|

|

0.637 |

||||

| Spraying home (or yard) for mosquitoes | ||||||||||||

| Sprayed for mosquitoes (self or service) | 43.1 (569) | 43.7 | 33.7 | 44.4 | 37.7 | 42.6 | 43.2 | 82.3 | 22.9 | |||

| No home spraying | 56.9 (752) | 56.3 | 66.3 | 55.6 | 62.3 | 57.4 | 56.8 | 17.7 | 77.1 | |||

| Total no. | 1,321 | 1,222 | 95 | 971 | 321 | 615 | 595 | 446 | 873 | |||

| p value |

|

0.058 |

|

0.036

|

|

0.835 |

|

<0.001

|

||||

| Larvicide application† | ||||||||||||

| Has applied larvicide around home (self or family) | 31.3 (308) | 24.2 | 10.8 | 40.5 | 7.9 | 30.0 | 32.9 | 20.1 | 37.3 | |||

| Never applied larvicide around home (self or family) | 68.7 (675) | 75.8 | 89.2 | 59.5 | 92.1 | 70.0 | 67.1 | 79.9 | 62.7 | |||

| Total no. | 983 | 1,229 | 93 | 708 | 253 | 476 | 423 | 334 | 641 | |||

| p value |

|

0.002

|

|

<0.001

|

|

0.364 |

|

<0.001

|

||||

| Installing window or door screens | ||||||||||||

| Reports putting screens on windows, doors | 17.8 (236) | 17.4 | 22.1 | 17.6 | 18.5 | 18.0 | 18.7 | 18.1 | 17.5 | |||

| Does not report putting screens on windows, doors | 82.2 (1,093) | 82.6 | 77.9 | 82.4 | 81.5 | 82.0 | 81.3 | 81.9 | 82.5 | |||

| Total no. | 1,329 | 1,230 | 95 | 976 | 324 | 616 | 600 | 448 | 873 | |||

| p value | 0.247 | 0.715 | 0.771 | 0.803 | ||||||||

*All data indicate percentages unless otherwise indicated. Statistically significant differences (p<0.05 by Mann-Whitney U nonparametric test) are shown in boldface. WIC, Women, Infants, and Children Program (US Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service); ZPK, Zika prevention kit. †Among those having yards for which they are responsible, and where water was present.

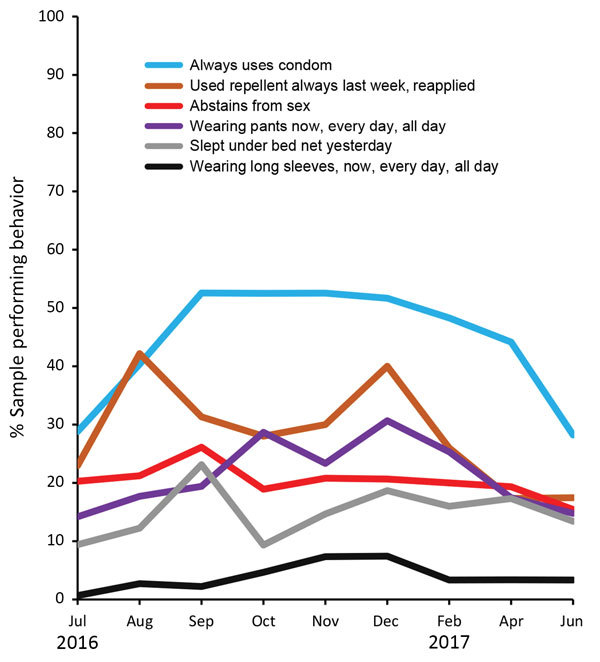

Over the monthly interview cohorts, the top level of condom use rose steadily with a sustained peak at over 50%, whereas mosquito repellent use rose to 42%, declined, and peaked again in December (Figure 2). Wearing long pants had 2 peaks (in October and December) near 30%, then a steep decline in 2017, whereas sexual abstinence stayed near 20%. Bed net use peaked at 23% in September, then fluctuated.

Figure 2.

Percentage of women reporting highest levels of 6 Zika personal protection behaviors, by interview month, Puerto Rico, July 2016–June 2017. August 12, 2016: President declares Zika in Puerto Rico a “public health emergency” (https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-usa/u-s-declares-a-zika-public-health-emergency-in-puerto-rico-idUSKCN10N2KA). September 30, 2016: Free residential spraying discontinued. Women who report the offer through December are referring to receiving the offer before September. October 28, 2016: First baby born with microcephaly in Puerto Rico (https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/29/health/zika-microcephaly-puerto-rico.html). June 5, 2017: Zika epidemic declared over by Puerto Rico Department of Health (https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20170605006235/en/Puerto-Rico-Department-Health-Declared-2016-Zika). WIC, Women, Infants, and Children Program (US Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service).

Zika Home Protection Behaviors

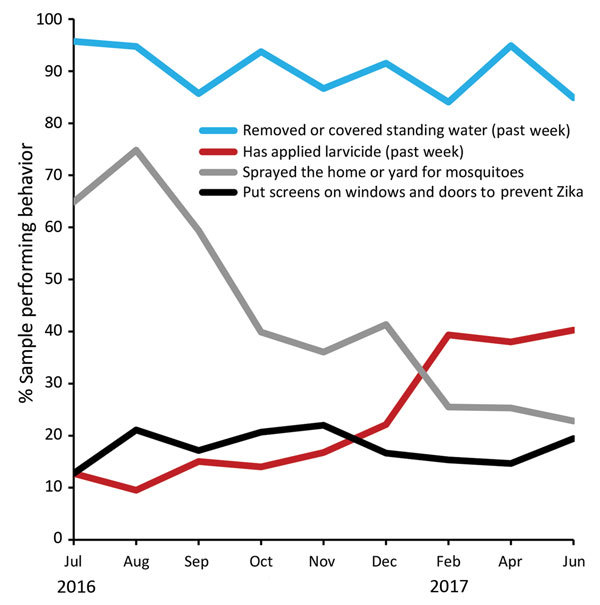

We ranked home protection behaviors, from the most frequent (removing standing water [90%]) to the least (installing window or door screens [18%]) (Table 5). Over time, removing standing water declined slightly through September but then remained at >85%, whereas spraying the home for mosquitoes had a steep decline during August–June 2017 (Figure 3). In contrast, larvicide application began low (13%) and then increased through June 2017 (40%).

Figure 3.

Percentage of women reporting highest levels of 4 Zika home protection behaviors, by interview month, Puerto Rico, July 2016–June 2017. August 12, 2016: President declares Zika in Puerto Rico a “public health emergency” (https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-zika-usa/u-s-declares-a-zika-public-health-emergency-in-puerto-rico-idUSKCN10N2KA). September 30, 2016: Free residential spraying discontinued. Women who report the offer through December are referring to receiving the offer before September. October 28, 2016: First baby born with microcephaly in Puerto Rico (https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/29/health/zika-microcephaly-puerto-rico.html). June 5, 2017: Zika epidemic declared over by Puerto Rico Department of Health (https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20170605006235/en/Puerto-Rico-Department-Health-Declared-2016-Zika). WIC, Women, Infants, and Children Program (US Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service).

Independent Associations between Interventions and Zika Prevention Behaviors

In multivariable logistic regression models, we observed a strong association between the offer of free residential mosquito spraying services and spraying the home for mosquitoes (Table 6). We also observed strong associations between ZPK receipt and larvicide application and between ZPK receipt and bed net use.

Table 6. Logistic regression models for Zika prevention behaviors performed by pregnant women that were significantly associated with >1 Zika prevention interventions, Puerto Rico, July 2016–June 2017*†.

| Behavior | Odds ratio (95% CI) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Received ZPK | Recalled Detén el Zika campaign | Received WIC Zika orientation | Offered free residential spraying | |

| Personal protection behaviors | ||||

| Bed net use | 3.1 (1.9–5.1) | 1.2 (0.8–1.7) | 2.2 (1.0–4.8) | NA |

| Condom use‡ | 1.4 (0.9–2.1) | 1.4 (1.0–2.0) | 2.4 (1.2–4.7) | NA |

| Mosquito repellent use | 1.5 (1.1–2.0) | 1.6 (1.2–2.1) | 1.2 (0.8–1.9) | NA |

| Sexual abstinence | 0.9 (0.6–1.4) | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) | 1.2 (0.5–2.5) | NA |

| Wearing long sleeves | 1.9 (0.6–6.2) | 2.9 (0.9–8.8) | 1.9 (0.2–14.9) | NA |

| Wearing long pants |

1.1 (0.7–1.7) |

1.0 (0.7–1.5) |

1.4 (0.6–3.0) |

NA |

| Home protection behaviors | ||||

| Larvicide application | 8.0 (4.8–13.3) | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | 2.7 (1.4–5.5) | 0.4 (0.3–0.5) |

| Spraying home or yard for mosquitoes | 1.5 (1.1–2.3) | 1.0 (0.7–1.4) | 1.6 (0.9–2.9) | 13.1 (8.5–20.3) |

| Removing or covering standing water | 2.2 (0.8–5.7) | 2.7 (1.1–6.5) | 0.5 (0.1–4.4) | 1.1 (0.4–2.9) |

| Installing window or door screens | 0.8 (0.6–1.2) | 0.8 (0.6,1.2) | 0.7 (0.4–1.5) | 0.9 (0.6–1.5) |

*Bold indicates significant result. WIC, Women, Infants, and Children Program (US Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service); ZPK, Zika prevention kit. †Models for WIC orientation and offer of free residential spraying were modeled separately, whereas ZPK distribution and Detén el Zika recall were modeled together to measure independent effects. Thus, each Zika prevention behavior had 3 models. To reduce possible bias associated with sparse data, calendar month of interview was consolidated into a 3-level, 3-month variable. All 5 demographic variables and consolidated calendar month of interview were controlled for in each model, except for the following cases: 1) WIC orientation did not include any calendar month of interview variable; or 2) very few respondents did not receive WIC orientation, thus the naturally occurring control group was very small. To not bias the models, no time of interview variable was included in models of WIC orientation. Education was excluded from bed net, larvicide, and repellent use models. Because of the substantial amount of missing data for education, additional testing was performed to determine whether women with missing education data performed the 10 behaviors with significantly higher or lower frequency. Three behaviors (repellent, bed net, and larvicide use) were significantly associated with whether education data were missing, so education was not included in these models. No calendar month or consolidated month variable was used for any of the larvicide use models because of small cell sizes. ‡Among those reporting having had sex during pregnancy.

Discussion

For each intervention, exposure patterns corresponded with implementation history; WIC orientation exposure was consistently high, Detén el Zika campaign exposure grew over time, ZPK exposure faltered (because of logistical problems with kit distribution) and then recovered, and the free offer of home mosquito spraying was widely received during the offer period. These largely successful implementations illustrate the benefits of collaborating with a trusted local partner like WIC. WIC was able to incorporate Zika orientations into its regular programming, distribute ZPKs effectively, and provide the free offer of home spraying a WIC visit. WIC also played an important role in developing the Detén el Zika messaging.

Performance of Zika prevention behaviors varied widely. Nearly all women removed any standing water that they saw, and about three quarters usually or always used mosquito repellent, but very few wore long sleeves or put up screens. These findings are consistent with the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System Zika Postpartum Emergency Response (PRAMS-ZPER) study of postpartum women in Puerto Rico (22). Despite important methodologic differences between PRAMS-ZPER and our analysis, reported frequencies were similar for mosquito repellent use, removing standing water, bed net use, and wearing long sleeves. Where frequencies diverged (condom use and spraying home for mosquitoes), WIC sample frequencies were more similar to PRAMS-ZPER when limited to women in their third trimester. In contrast, interview data from US Virgin Islands in late 2016 (7) showed lower frequencies of using repellent, using condoms, removing standing water, and spraying home for mosquitoes. Only data for bed net use were similar to the results of our analysis.

Overall, the ZPK distribution had the greatest number of independent positive associations with Zika prevention behavior and some of the strongest associations. This finding is consistent with a small but growing body of literature demonstrating the effectiveness of distributing items for encouraging prevention behavior (11,23,24). Prevention kits containing prevention products for at-risk populations should be considered a best practice, particularly in low-resource settings.

Larvicide use and bed net use were independently associated with ZPK receipt, and distributing items associated with these 2 largely unfamiliar behaviors probably increased use because women were then able to try them. According to Rogers’ diffusion of innovations theory (25), the ability to try a new behavior and observe the results enhances the likelihood of adoption. Larvicide application might have been further enhanced by what Rogers calls “relative advantage”; that is, the intervention might have been popular because it was easier to implement than the other 3 recommended home protection behaviors (removing standing water, installing screens, and spraying home for mosquitoes). Many of the ZPKs in the early months of tracking were missing larvicide tablets; thus, the dramatic increase in larvicide use over the period is not surprising. The finding also suggests that the actual association between ZPKs and larvicide use is stronger than what our results indicate, given that the incomplete kits might have diluted the observed association.

Offer of free residential mosquito spraying services was strongly associated with spraying the home for mosquitoes, enabling women to overcome both cost and logistical barriers. Although efficacy concerns led to discontinuation of the spraying program, the offer had a strong association with spraying behavior, a finding consistent high percentage (81%) of respondents who rated the offer of insecticide spraying to pregnant women as very important.

The Detén el Zika campaign had the greatest independent effect on removing standing water, significant effects for repellent use, and modest (marginally significant) effects for condom use, whereas the WIC orientation appeared to have a slightly greater effect on condom use. Although WIC Zika orientation did not yield the same large number of positive associations in regression models as was observed in the bivariate analyses, its highly successful implementation left it with a very small natural control group, which might have limited the utility of modeling for this intervention.

As we consider the public health implications of these results, we should note that in the context of cross-sectional data with outcomes that are not rare, ORs do not equate to relative risk. Thus, we cannot say that women receiving the free offer of home mosquito spraying were 13 times more likely to spray their homes. Unfortunately, estimating relative risks from ORs is not straightforward. Simple conversion formulas (26) have been shown to be imprecise (27), but such conversions can provide at least a rough sense of the extent to which relative risk is more modest than odds with nonrare outcomes (28). For example, the ORs of 8.0 (ZPK exposure and larvicide application), 13.1 (offer of free residential spraying and spraying home for mosquitoes), and 3.1 (ZPK exposure and bed net use) roughly convert to risk ratios of 5.2, 3.5, and 2.7, respectively, whereas the more modest ORs of 2.7 (Detén el Zika campaign exposure and removing standing water and WIC orientation and larvicide application) and 2.4 (WIC orientation and condom use) undergo a smaller adjustment (1.1, 2.2 and 1.7, respectively). Further research is needed to evaluate these associations more precisely.

In our exploration of intervention mechanisms, the 2 interpersonal communication variables showed stronger association with the interventions and to the Zika prevention behaviors than did the individual variables (Zika concern, perceived likelihood of infection, and self-confidence). This finding suggests that the interpersonal factors were more influential on behavior than individual risk perceptions. Interpersonal communication has long been recognized as an important mediator of the effects of educational campaigns on health-related behavior change (29–33), and our results confirm this assertion.

The main challenge of this analysis was that the data were collected during an emergency response for nonresearch purposes, meaning that much of the analysis design had to be created after the fact, particularly the creation of Zika behavior outcome variables. Further, this analysis did not use an optimal research design (i.e., there were no pre–post groups or predesignated control groups). The resulting imbalances in naturally occurring control groups prevented the use of a single logistic model for all 4 interventions. However, the use of random sampling from a frame representing 87% of the island’s pregnant women and logistic regression modeling to control confounding by demographic factors provide a credible first look at possible effects of Zika prevention interventions during an epidemic response.

Among the 4 intervention strategies, ZPK distribution appears to have significant independent effects on the greatest number of Zika prevention behaviors. Consistent with the literature, this intervention should be considered a best practice for behavioral support in infectious disease outbreaks, particularly in low-resource settings. Social context factors appeared to be more influential in Zika prevention behavior than personal risk assessment and self-efficacy factors, whereas Zika prevention behaviors that enable women to try out lesser-known behaviors appeared to garner greater acceptance than other behaviors. Areas for future research include developing the evidence base for Zika prevention behavior effectiveness and more precise quantification of intervention mechanisms and effects.

Supplemental information on development of Zika prevention behavior scales and logistic regression models.

Acknowledgments

We thank the pregnant women across Puerto Rico who gave their time and experience to participate in the interviews; the Puerto Rico Department of Health Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) Program leaders and staff; Brenda Rivera-Garcia, Carla Espinet Crespo, Tyler Sharp, Steve Waterman, Katherine Lyon Daniel, Amy McMillen, John O’Connor, Carmen Perez, Nicki Pesik, Lyle Petersen, Lee Samuel, Eunice Soto, Laura Youngblood, Jeffrey Zirger, Mahmoud K. Aboukheir, Consuelo Abriles, Jorge Carlo, Pollyanna R. Chavez, Alexander Cruz-Benitez, Gabriela Escutia, Roberta Lugo, Gisela Medina, Brian D. Montalvo-Martínez, Carlos G. Grana-Morales, Rosalyn Plotzker, Clarissa Valdez, Santos Villarán, and Max Zarate-Bermudez.

Biography

Dr. Earle-Richardson is an epidemiologist and behavioral scientist with CDC’s National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases. Her research interests include the relationship between human behavior and health, the role of behavioral science in emergency response, and how culture affects health.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Earle-Richardson GB, Prue C, Turay K, Thomas D. Influences of community interventions on Zika prevention behaviors of pregnant women, Puerto Rico, July 2016–June 2017. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018 Dec [date cited]. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2412.181056

Preliminary results from this study were presented as a poster presentation at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases, August 29, 2018, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

References

- 1.Rasmussen SA, Jamieson DJ, Honein MA, Petersen LR. Zika virus and birth defects—reviewing the evidence for causality. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1981–7. 10.1056/NEJMsr1604338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas DL, Sharp TM, Torres J, Armstrong PA, Munoz-Jordan J, Ryff KR, et al. Local Transmission of Zika Virus—Puerto Rico, November 23, 2015-January 28, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:154–8. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6506e2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petersen LR, Jamieson DJ, Powers AM, Honein MA. Zika Virus. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1552–63. 10.1056/NEJMra1602113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Michie S, Atkins L, West R. The behaviour change wheel. A guide to designing interventions. London: Silverback Publishing; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones KE, Yan Y, Colditz GA, Herrick CJ. Prenatal counseling on type 2 diabetes risk, exercise, and nutrition affects the likelihood of postpartum diabetes screening after gestational diabetes. J Perinatol. 2018;38:315–23. 10.1038/s41372-017-0035-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whitlock EP, Orleans CT, Pender N, Allan J. Evaluating primary care behavioral counseling interventions: an evidence-based approach. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22:267–84. 10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00415-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prue CE, Roth JN Jr, Garcia-Williams A, Yoos A, Camperlengo L, DeWilde L, et al. Awareness, beliefs, and actions concerning Zika virus among pregnant women and community members—U.S. Virgin Islands, November–December 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:909–13. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6634a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Samaritan’s Purse. Samaritan’s Purse launches bold new initiative to combat Ebola [cited 2018 Feb 28]. https://www.samaritanspurse.org/our-ministry/samaritans-purse-launches-bold-new-initiative-to-combat-ebola-10-07-14-press-release

- 9.Sifferlin A. This is how Ebola Patients are equipping their homes [cited 2018 Feb 9]. http://time.com/3481394/equipping-homes-to-treat-ebola-patients

- 10.Meltzer MI, Atkins CY, Santibanez S, Knust B, Petersen BW, Ervin ED, et al. Estimating the future number of cases in the Ebola epidemic—Liberia and Sierra Leone, 2014–2015. MMWR Suppl 2014;63:1–14. PMID 25254986 [PubMed]

- 11.Colindres P, Mermin J, Ezati E, Kambabazi S, Buyungo P, Sekabembe L, et al. Utilization of a basic care and prevention package by HIV-infected persons in Uganda. AIDS Care. 2008;20:139–45. 10.1080/09540120701506804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mabude ZA, Beksinska ME, Ramkissoon A, Wood S, Folsom M. A national survey of home-based care kits for palliative HIV/AIDS care in South Africa. AIDS Care. 2008;20:931–7. 10.1080/09540120701768438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.International RTI. Detén el Zika/Stop Zika Campaign, a comprehensive education campaign to fight the Zika epidemic in Puerto Rico [cited 2018 Feb 9]. https://www.rti.org/impact/DeténDetén-el-zika-stop-zika-campaign

- 14.Wakefield MA, Loken B, Hornik RC. Use of mass media campaigns to change health behaviour. Lancet. 2010;376:1261–71. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60809-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boene H, González R, Valá A, Rupérez M, Velasco C, Machevo S, et al. Perceptions of malaria in pregnancy and acceptability of preventive interventions among Mozambican pregnant women: implications for effectiveness of malaria control in pregnancy. PLoS One. 2014;9:e86038. 10.1371/journal.pone.0086038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piltch-Loeb R, Abramson DM, Merdjanoff AA. Risk salience of a novel virus: US population risk perception, knowledge, and receptivity to public health interventions regarding the Zika virus prior to local transmission. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0188666. 10.1371/journal.pone.0188666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jambulingam P, Gunasekaran K, Sahu S, Vijayakumar T. Insecticide treated mosquito nets for malaria control in India-experience from a tribal area on operational feasibility and uptake. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2008;103:165–71. 10.1590/S0074-02762008005000009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adams L, Bello-Pagan M, Lozier M, Ryff KR, Espinet C, Torres J, et al. Update: ongoing Zika virus transmission—Puerto Rico, November 1, 2015–July 7, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:774–9. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6530e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.BusinessWire. The Puerto Rico Department of health has declared that the 2016. Zika epidemic is over; Zika transmission has substantially decreased in Puerto Rico below epidemic levels [cited 2018 Feb 28]. https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20170605006235/en/Puerto-Rico-Department-Health-Declared-2016-Zika

- 20.Greenland S, Mansournia MA, Altman DG. Sparse data bias: a problem hiding in plain sight. BMJ. 2016;352:i1981. 10.1136/bmj.i1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics. US Territories, 2016. natality public use file [cited 2018 Feb 8]. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data_access/vitalstatsonline.htm

- 22.D’Angelo DV, Salvesen von Essen B, Lamias MJ, Shulman H, Hernandez-Virella WI, Taraporewalla AJ, et al. Measures taken to prevent Zika virus infection during pregnancy Puerto Rico, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:574–8. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6622a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robinson MN, Tansil KA, Elder RW, Soler RE, Labre MP, Mercer SL, et al. ; Community Preventive Services Task Force. Mass media health communication campaigns combined with health-related product distribution: a community guide systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47:360–71. 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.05.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noar SM. A 10-year retrospective of research in health mass media campaigns: where do we go from here? J Health Commun. 2006;11:21–42. 10.1080/10810730500461059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. Fifth edition. New York: Free Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang J, Yu KF. What’s the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA. 1998;280:1690–1. 10.1001/jama.280.19.1690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McNutt LA, Hafner JP, Xue X. Correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA. 1999;282:529. 10.1001/jama.282.6.529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McNutt LA, Wu C, Xue X, Hafner JP. Estimating the relative risk in cohort studies and clinical trials of common outcomes. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:940–3. 10.1093/aje/kwg074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rogers EM. A prospective and retrospective look at the diffusion model. J Health Commun. 2004;9(Suppl 1):13–9. 10.1080/10810730490271449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31:143–64. 10.1177/1090198104263660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jeong M, Bae RE. The effect of campaign-generated interpersonal communication on campaign-targeted health outcomes: a meta-analysis. Health Commun. 2018;33:988–1003. 10.1080/10410236.2017.1331184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gainforth HL, Latimer-Cheung AE, Athanasopoulos P, Moore S, Ginis KA. The role of interpersonal communication in the process of knowledge mobilization within a community-based organization: a network analysis. Implement Sci. 2014;9:59. 10.1186/1748-5908-9-59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Katz E, Lazarsfeld P, Roper E. Personal influence. New York: Routledge; 2005. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental information on development of Zika prevention behavior scales and logistic regression models.