Drug repurposing affords the implementation of new treatments at a moderate cost and under a faster time-scale. Most of the clinical drugs against Leishmania share this origin.

KEYWORDS: Leishmania, antidepressant, bioenergetics, drug repurposing, metabolomics, sertraline

ABSTRACT

Drug repurposing affords the implementation of new treatments at a moderate cost and under a faster time-scale. Most of the clinical drugs against Leishmania share this origin. The antidepressant sertraline has been successfully assayed in a murine model of visceral leishmaniasis. Nevertheless, sertraline targets in Leishmania were poorly defined. In order to get a detailed insight into the leishmanicidal mechanism of sertraline on Leishmania infantum, unbiased multiplatform metabolomics and transmission electron microscopy were combined with a focused insight into the sertraline effects on the bioenergetics metabolism of the parasite. Sertraline induced respiration uncoupling, a significant decrease of intracellular ATP level, and oxidative stress in L. infantum promastigotes. Metabolomics evidenced an extended metabolic disarray caused by sertraline. This encompasses a remarkable variation of the levels of thiol-redox and polyamine biosynthetic intermediates, as well as a shortage of intracellular amino acids used as metabolic fuel by Leishmania. Sertraline killed Leishmania through a multitarget mechanism of action, tackling essential metabolic pathways of the parasite. As such, sertraline is a valuable candidate for visceral leishmaniasis treatment under a drug repurposing strategy.

INTRODUCTION

Leishmaniasis encompasses the different pathologies caused by infection with the species of the human protozoan parasite Leishmania. The clinical symptomatology of this disease depends on the infective species of Leishmania and on the immunological status of the host, ranging from the usually mild cutaneous forms of the disease to the visceral syndrome, which is highly lethal if untreated (1). Leishmaniasis accounts for 10 to 12 million infected people worldwide and nearly 50,000 deaths per year in 98 countries where the disease is endemic (2).

To date, no safe and reliable human vaccine for leishmaniasis is commercially available (3, 4). This leaves chemotherapy, based on only a small number of drugs, the sole treatment for this disease. Until some years ago, organic pentavalent antimonials were the benchmark of visceral leishmaniasis treatment, despite their severe side effects and rising resistance in areas where leishmaniasis is endemic (5). New alternative therapies, such as liposomal amphotericin B (6), paromomycin (7), and the oral drug miltefosine (8), were more recently introduced. However, they are far from satisfactory. The therapeutic failure of miltefosine in India and Nepal rose from an initial 5% at its initial implementation in 2002 up to 20% in a few years (9).

Combination therapy (10, 11) and drug repurposing (12, 13) are short- and medium-term strategies to cope with this threat until the appearance and approval of better drugs. The synergism of combined drugs tackling different pharmacological targets improves the efficacy of the treatment and reduces the length and toxicity associated with monotherapy, as well as the risk of resistance induction (11). Drug repurposing profits from using approved clinical drugs for their implementation against new pathologies, saving most of the time and costs required to develop new drugs (13). Indeed, many of the current leishmanicidal drugs emerged from drug repurposing; amphotericin B, miltefosine, and the aminoglycoside paromomycin were formerly developed as antifungal (14), anticancer (15), or antibacterial (16) drugs, respectively. At present, drug repurposing strategies strongly contribute to the quest for new and better leishmaniasis treatments. Nitroheterocyclic compounds such as fexinidazole, oxaboroles, and delamanide (17), formerly reported as African trypanocidal, antifungal, and antimycobacterial agents, respectively, or the antitumoral aminopyrazole are or have been under trial as new clinical leishmanicidal drugs (18, 19).

Along this line, sertraline [SRT; (1S,4S)-N-methyl-4-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-1-naphthylamine] is an appealing candidate for drug repurposing. Sertraline is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), heavily prescribed for depression or anxiety disorders in the United States, with acceptable side-effect and tolerability profiles (20, 21). As a repurposed drug, SRT showed a broad antimicrobial spectrum (22–25), such as in animal models against Leishmania infection (26), and even antiviral activity against the Ebola virus (27).

Sertraline potentiates the serotonin-based neurotransmission by inhibition of the serotonin/5-HT reuptake transporter (hSERT/5-HTT/SLC6A4), thus increasing the SRT concentration at the synapsis (28). BLAST analyses reported no counterpart Leishmania protein either to hSERT/5-HTT/SLC6A4 or to LeuT, a bacterial amine transporter targeted by SSRIs and tricyclic antidepressants (29, 30). The quest to define the Leishmania target for SRT is even more puzzling, since its wide microbicidal spectrum cannot be solely based on its inhibition of the variety of efflux pumps reported for a wide diversity of cells and microorganisms (22, 31).

The mitochondrion was identified as one of the SRT targets against Leishmania (26). In the present study, a detailed insight into the leishmanicidal mechanism of SRT was pursued. To this end, an unbiased approach using a metabolomics multi-analytical platform, associated with the determination of bioenergetic parameters, was applied. Our results not only confirmed the mitochondrion as a prominent SRT target in Leishmania but also unveiled the considerable extent and severity of the metabolic disarray caused by this drug. As a consequence, sertraline is endorsed as an appealing candidate for future development as a leishmanicidal drug.

RESULTS

Leishmanicidal activity of sertraline.

The detrimental effects of SRT on L. infantum promastigotes were assessed under different assay conditions using the inhibition of MTT [3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide] reduction as a readout. Sertraline inhibited the proliferation of L. infantum promastigotes in rich growth medium with a 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) and an IC90 of 2.0 ± 0.7 µM and 8.4 ± 1.8 µM, respectively, whereas for intracellular amastigotes, the respective IC50 and IC90 values were 3.9 ± 0.3 µM and 7.9 ± 0.1 µM. SRT was not toxic for murine peritoneal macrophages at the highest concentration tested (80 µM); thus, its selective index is >20. To evaluate the short-term effects of SRT on promastigotes, promastigotes were incubated with the drug for 4 h in Hanks medium supplemented with 10 mM d-glucose (HBSS-Glc). Under these conditions, IC50 and IC90 values for MTT reduction were 20.8 ± 4.5 µM and 85.9 ± 3.9 µM, respectively. The induction of SRT resistance was quite scarce; the initial IC50 (2.0 μM) barely increased to 5.0 μM after promastigote growth under sertraline pressure for 8 months (data not shown).

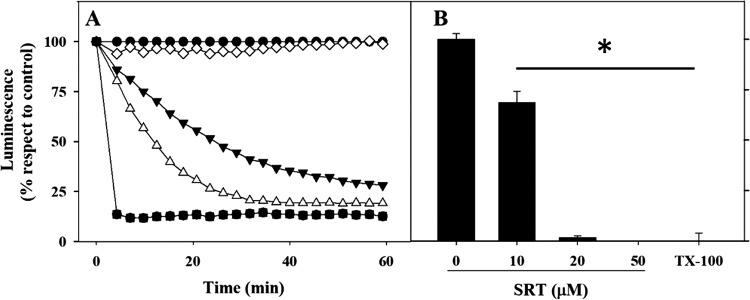

Real-time monitoring of ATP levels in living 3-Luc L. infantum promastigotes.

The intracellular level of ATP provides a reliable insight into the metabolic status of the parasite. To this end, real-time variations of the cytoplasmic level of ATP after SRT addition were monitored in L. infantum promastigotes from the 3-luc line. These parasites express a firefly luciferase with a mutated C-terminal tripeptide that prevents its import into the glycosome. In the presence of the free- membrane permeable DMNPE-d-luciferin [d-luciferin 1-(4, 5-dimethoxy-2-nitrophenyl) ethyl ester], a caged substrate for luciferase, ATP is the limiting substrate for the luminescence output of these living parasites (32). SRT inhibited the luminescence of 3-Luc promastigotes in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1). At the IC50 value of SRT in HBSS-Glc (20 μM), the luminescence decreased more than 70% after 1 h of incubation (Fig. 1A) and reached full inhibition at 4 h (Fig. 1B). Therefore, SRT induced a fast and severe bioenergetic collapse in Leishmania promastigotes.

FIG 1.

Inhibition of luminescence in living 3-Luc L. infantum promastigotes by sertraline. (A) Time-course of luminescence decay in 3-Luc promastigotes after sertraline addition. 3-Luc parasites under standard conditions of assay were incubated with 25 μM DMNPE-luciferin, sertraline was added at t = 0 (100% luminescence), and the variation in luminescence was monitored. Control, untreated parasites are indicated by open triangles. Concentrations: 10 μM SRT (inverted solid triangles), 20 μM SRT (open circles), 50 μM SRT (solid circles), 0.1% Triton X-100 (solid squares). (B) Inhibition of luminescence of promastigotes after 4 h of incubation with different concentrations of sertraline. Parasites were incubated with sertraline; afterward, DMNPE-luciferin was added, and the highest value of luminescence reached is represented. Luminescence is referred to as a percentage with respect to untreated parasites (means ± the SD). The results shown are representative of two experiments carried out independently (*, P < 0.05).

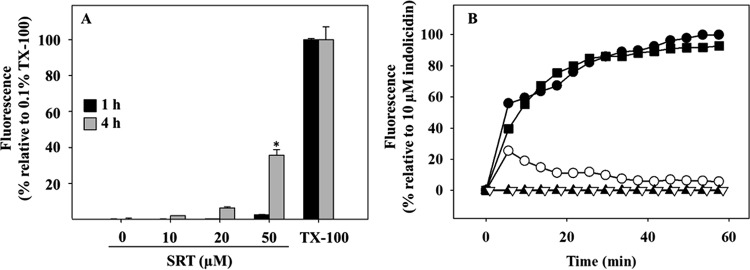

Plasma membrane damage induced by sertraline on L. infantum promastigotes.

Plasma membrane permeabilization is a feasible cause for the bioenergetic collapse of Leishmania by SRT. To test this hypothesis, entry of the vital dye SYTOX Green (molecular weight, 600) into the promastigotes was measured. To this end, the increase in fluorescence of the probe caused by its binding to intracellular nucleic acids was monitored (Fig. 2A), a process precluded in cells with unscathed plasma membrane. SYTOX Green fluorescence only increased beyond 20 μM SRT and after 4 h of incubation; in contrast, the decrease in intracellular ATP was noticeable just 15 min after SRT addition. To rule out a subtler membrane permeabilization, plasma membrane depolarization was also measured, since depolarization is exclusively dependent on the permeability of the membrane to monovalent ions (33). Depolarization was assessed by the increase in the fluorescence of the potential-sensitive anionic dye bisoxonol after its insertion into the membrane, which is prevented in polarized cells (34). Near its IC50 value (20 μM), SRT only caused a modest depolarization, although it reached completion at 50 µM SRT, similar to that produced by 10 μM indolicidin, a membrane-active leishmanicidal peptide (Fig. 2B).

FIG 2.

Permeabilization of the plasma membrane of L. infantum promastigotes by sertraline. (A) SYTOX Green fluorescence entrance into L. infantum promastigotes induced by sertraline. Parasites were treated under standard assay conditions with the specified sertraline concentrations for 1 h (black columns) or 4 h (gray columns). Afterward, SYTOX Green (1 μM, final concentration) was added, and fluorescence was assessed (λEXC = 485 nm; λEM = 520 nm). Fully permeabilized parasites (100% fluorescence) were obtained by the addition of 0.1% Triton X-100. (B) Depolarization of the plasma membrane of L. infantum promastigotes. Promastigotes were assayed under standard conditions in the presence of bisoxonol (0.2 μM). Sertraline at the specified concentration was added (t = 0), and changes in fluorescence (λEXC = 544 nm; λEM = 584 nm) were recorded. Fully depolarized parasites were obtained by treatment with 10 μM indolicidin. Concentrations: 0 μM SRT (open triangles), 10 μM SRT (solid triangles), 20 μM SRT (open circles), 50 μM SRT (solid circles), 10 μM indolicidin (solid squares). The results shown are representative of two experiments carried out independently (*, P < 0.05).

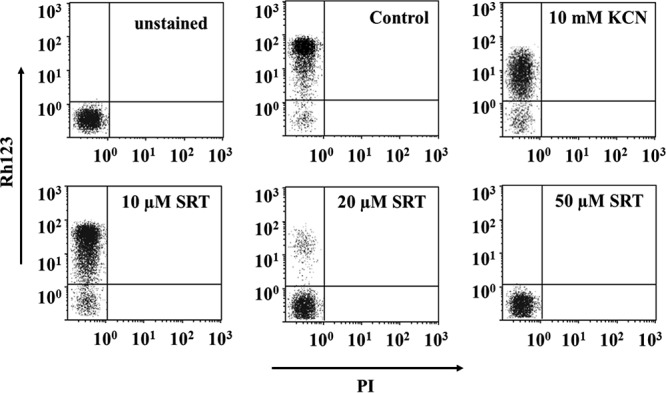

Assessment of changes in mitochondrion functionality by SRT in L. infantum promastigotes.

Once plasma membrane permeabilization was ruled out as the main mechanism for the decrease in ATP, its production, mostly due to oxidative phosphorylation in Leishmania, was assessed. The electrochemical potential of the mitochondrion (Δψm) is the driving force both for ATP synthesis and for the almost exclusive intracellular accumulation of rhodamine-123 (Rh123) into the mitochondrion. Sertraline decreased Rh123 accumulation in L. infantum promastigotes in a concentration-dependent manner, as measured by flow cytometry (Fig. 3). The normalized mean percentages of Rh123 accumulation ± the standard deviations (SD) referred to untreated parasites were 49.4 ± 16.3%, 0.4 ± 0.2%, and 0.0 ± 0.1% for promastigotes treated with 10, 20, or 50 μM SRT, respectively, and 24.8 ± 0.1% for parasites incubated with 10 mM KCN (Fig. 3). Severely damaged parasites were identified by abnormal scattering values and excluded from the study by gating the right population.

FIG 3.

Variation of rhodamine-123 accumulation in L. infantum promastigotes caused by sertraline. Promastigotes were treated with sertraline at different concentrations for 4 h and loaded with Rh123 (0.3 μM, 5 min); propidium iodide (PI; 0.5 µg/ml) was added to the samples immediately before their analysis by flow cytometry. Fluorescence settings: Rh123 fluorescence (y axis; λEXC, 488 nm; λEM, 520 nm) and PI fluorescence (x axis, λEXC = 488 nm; λEM = 620 nm). Parasites with a depolarized mitochondrion were obtained by treatment with 10 mM KCN. Control (untreated) parasites were also included.

The decrease in Δψm induced by SRT was also tested on amastigotes due to the severe metabolic retooling undergone through their transformation from promastigotes, as well as by the higher contribution of the mitochondrion to the amastigote metabolism (35). Since the induction of L. infantum axenic amastigotes from promastigotes by temperature and pH stress gave poorly reproducible results, we used an Leishmania pifanoi axenic amastigote line with a well-established similarity to amastigotes obtained from lesions, including metabolism (reviewed in reference 36). The percentages of Rh123 accumulation by L. pifanoi axenic amastigotes with respect to untreated amastigotes were 47.6 ± 5.6%, 18.9 ± 2.1%, and 5.0 ± 0.1% after 4 h of incubation with 10, 20, or 50 μM SRT, respectively. The percentage for those was 36.0 ± 4.3%, as illustrated in Fig. S1. Under these experimental conditions, the IC50 for SRT for L. pifanoi axenic amastigotes was 13.5 ± 3.7 µM.

In all experiments, the mitochondrial depolarization induced by SRT was preserved on amastigotes.

Sertraline also induced morphological changes in the promastigote mitochondrion. SRT-treated promastigotes showed a more fragmented MitoTracker Red fluorescence pattern with respect to untreated parasites (Fig. S2).

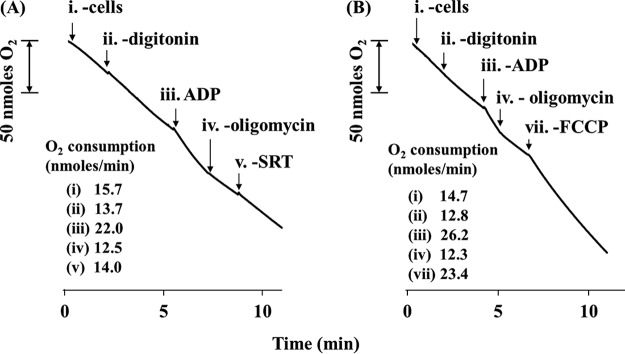

Effects of sertraline on the respiration of L. infantum promastigotes.

The oxygen consumption rate of living parasites increased from an initial value of 15.9 nmol O2/(min × 108 cells) to 18.4 nmol O2/(min × 108 cells) 2.5 min after 50 μM SRT addition (data not shown). This result was further confirmed in digitonin-permeabilized parasites, using succinate as the substrate for complex II (Fig. 4). Maintenance of inner mitochondrial membrane permeability was evidenced by the increase in the respiration rate after ADP addition (state III). Once the respiratory chain was inhibited by oligomycin at the level of complex V (ATP synthase), the addition of SRT increased the respiration rate by 11.0% (11.6 ± 0.9%, average of the three experiments performed) (Fig. 4A), behaving as a mitochondrial uncoupler, but milder than FCCP [carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazine], a typical uncoupling agent (Fig. 4B).

FIG 4.

Sertraline effects on the respiratory chain of L. infantum promastigotes. Parasites were resuspended in respiration buffer at 108 cells/ml in a Clark oxygen electrode. Succinate was used as the sole substrate. Oxygen consumption rates of L. infantum promastigotes were calculated from the corresponding slope and are expressed as nmol O2/min. (A) Uncoupling activity of sertraline on digitonized parasites. (B) Respiration controls in untreated parasites. Traces are representative of one of three independent experiments. Reagent concentrations: 60 µM digitonin, 100 µM ADP, 12.6 µM oligomycin, 3.3 µM FCCP, and 50 µM SRT. Arrows represent the addition of the respective reagents.

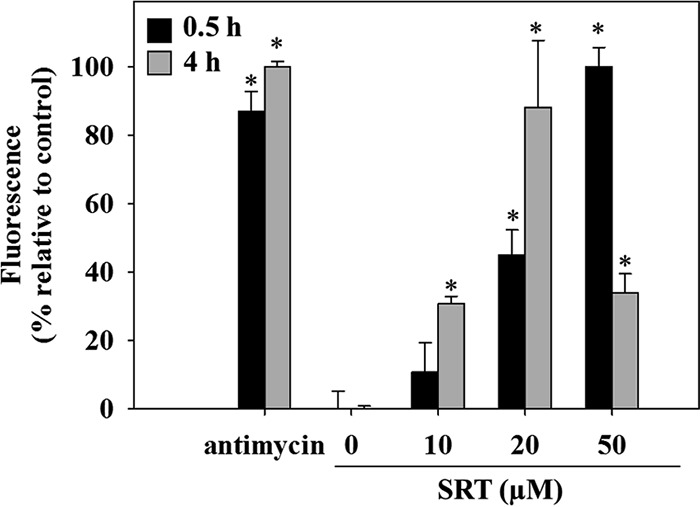

The uncoupling of the respiratory chain at 20 μM SRT led to an increased ROS (reactive oxygen species) production. This was assessed by the increase in MitoSOX fluorescence, measured 30 min after drug addition (Fig. 5). For longer incubations (4 h), ROS production equaled that obtained for the positive control (0.3 μg/ml antimycin A). The decrease in fluorescence observed at the highest SRT concentration (50 µM) likely resulted from the death of the parasites.

FIG 5.

Mitochondrial ROS generation in L. infantum promastigotes induced by sertraline. Parasites were preloaded with 5 µM MitoSOX Red and incubated for 0.5 h (black column) or 4 h (gray column) with different concentrations of sertraline. Increment of MitoSOX Red fluorescence was assessed by flow cytometry (λEXC = 488 nm; λEM = 520 nm). Antimycin A (0.3 µg/ml) was used as a positive control for ROS generation and is taken as 100% fluorescence. The results shown are representative of two experiments carried out independently (*, P < 0.05).

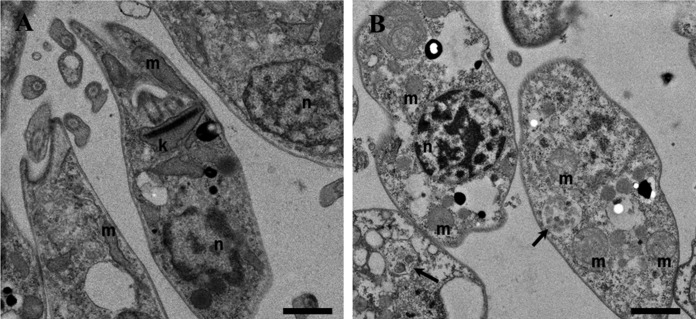

Electron microscopy of L. infantum promastigotes treated with sertraline.

The most relevant morphological features of promastigotes treated with SRT (20 μM, 4 h) are shown in Fig. 6. Sertraline-treated promastigotes displayed a strong cytoplasmic vacuolization with vesicles inside the vacuoles, acidocalcisomes with poor membrane definition, and DNA condensation inside the nucleus. The mitochondrion morphology appeared altered, forming a round vesicular pattern compared to untreated parasites. Finally, the plasma membranes of promastigotes showed no significant alterations after 4 h of incubation, a finding in agreement with the entry of SYTOX green vital dye at this SRT concentration.

FIG 6.

Transmission electron microscopy of L. infantum promastigotes treated with sertraline. (A) Control parasites. (B) Promastigotes treated with 20 μM sertraline (IC50) for 4 h. Legend: mitochondrion, m; nucleus, n; kinetoplast, k. Arrows indicate multivesicular vacuoles. Magnification, 1 μm.

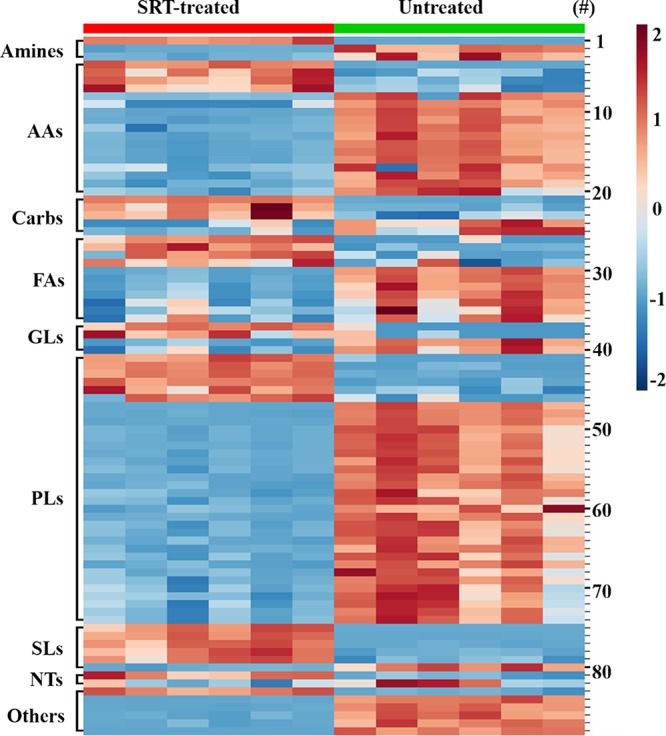

Metabolomic validation of the leishmanicidal mechanism of sertraline.

In order to confirm the overall dysfunction created by SRT on Leishmania metabolism, an unbiased metabolomic study was carried out. For this purpose, promastigotes were treated in growth medium for 12 h with 35 µM sertraline (∼IC70 under these experimental conditions) to ensure a significant metabolic effect while partially preserving parasite viability. The procedures are detailed in the supplemental material. First, data were evaluated by multivariate analysis. The tight cluster of the quality controls in a well-defined area of principal-component-analysis (PCA) plot evidenced the stability and reproducibility of the results obtained for both analytical platform capillary electrophoresis-mass spectrometry (CE-MS) and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) (Fig. S3). Afterward, a supervised partial square analysis-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) model was built for the different techniques (Fig. S4), showing in all cases a high value for R2 (explained variation) and Q2 (predictability power). The identity of the samples within a specific group was validated using the “leave 1/3 out” approach (cross-validation). Excluded samples were correctly predicted in 100% of cases validating the models and statistically supporting metabolite differences promoted by sertraline treatment. Together, the PCA and PLS-DA results permit foreseen strong markers classifying the groups.

Table S1 summarizes the number of features obtained for each step and the corresponding technique used. Those used in the assay were highly complementary respect to the chemical nature of the metabolites identified. The metabolites identified by CE-MS were preferentially of a polar nature. The groups with a higher percentage respect of total identified features were amino acids and peptides (68%), purines/pyrimidines (8%), and amines (8%). In LC-MS, phospholipids (48%), fatty acids (16%), sphingolipids and sphingoid bases (7%), and carbohydrates (7%) were the largest groups.

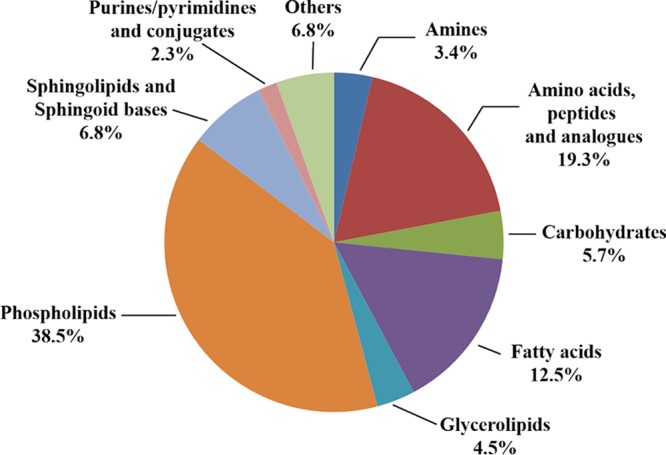

In short, 88 metabolites encompassing different biochemical classes changed after SRT treatment (IC70 of ∼35 µM). Table S2 compiles all metabolites with their statistical variation, represented in Fig. 7 as heatmap and as a percentage breakdown according to their different biochemical classes in Fig. 8.

FIG 7.

Heatmap of metabolites with significant variation after sertraline treatment of L. infantum promastigotes. Data obtained from LC-MS and CE-MS from parasites, treated or not treated with 35 μM SRT, were normalized to enable comparison between techniques. For this, the mean metabolite abundance was divided by the SD for each metabolite. Lines represent normalized abundances of metabolites. Columns correspond to the analysis of the different samples for each group. To assess the levels of metabolite variation, a color intensity scale accounting for the relative abundance is included at the right side, as well as the numbers for the specific metabolite (#) according to Table S2. The biochemical classes are indicated at the beginning of each block. The number at the right side of each line identifies the metabolite with respect to Table S2. AAs, amino acids and peptides; Carbs, carbohydrates; FAs, fatty acids; GL, glycerolipids; PLs, glycerophospholipids; SL, sphingolipids and sphingoid bases; NTs, purine and pyrimidine basis and their conjugates.

FIG 8.

Biochemical classification of metabolites with statistical variation obtained after sertraline treatment of L. infantum promastigotes. Percentages refer to the total numbers of features identified in Table S2.

The metabolism of lipids underwent the higher qualitative variation, accounting for 62.3% of all the identified changes, with decreases in lysophospholipids and an increase in sphingolipids and sphingoid bases. Variations in the nature of fatty acids did not follow a common trend and varied according to the lipid species identified.

After metabolic allocation of the identified features, a three-pronged actuation of SRT on Leishmania was disclosed: (i) polyamine and trypanothione biosynthesis (Fig. S5A). (ii) tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA cycle) and its intermediate precursors (Fig. S5B), and (iii) phospholipid and sphingolipid metabolism (Fig. S5C). A comprehensive view is included in Fig. S6.

DISCUSSION

Drug repurposing is an appealing alternative to tackle the increasing need for new treatments against Leishmania at moderate cost and with a relatively quick clinical implementation (13). For this goal, studies with antidepressants have yielded an extremely successful set of drugs such as ketanserin (37), mianserin (38), cyclobenzaprine (39), clomipramine, nitroimipramine, and imipramine (40).

From this standpoint, sertraline, a well-known oral antidepressant, differed from those mentioned above due to its tetrahydronaphthalene core as a chemical scaffold. SRT is an off-patent drug with high tolerability and has been tested successfully in animal models of visceral leishmaniasis (26). The concentration of SRT reported in human liver is 3.9 mg/kg (20), which is far higher than its leishmanicidal concentration. As such, it is an appealing leishmanicidal candidate. Furthermore, SRT is an amphiphilic weak base, acting as a lysosomotropic agent that accumulates inside acidic compartments as the parasitophorus vacuole of Leishmania by an ion-trapping effect (41). This property underlies the selectivity of SRT on intracellular Mycobacterium tuberculosis (42), even when the Mycobacterium vacuole is one pH unit less acidic than the parasitophorus vacuole for Leishmania, surmising a higher accumulation of SRT in the Leishmania vacuole. Although the leishmanicidal mechanism of SRT has been already partially unveiled (26), a deeper knowledge will be helpful in order to optimize combination therapies or to evaluate the risk of resistance induction.

No evident counterpart protein to the mammalian sertraline target was identified in Leishmania. The mitochondrial dysfunction in SRT-treated L. donovani parasites was formerly described by Palit and Ali (26). In the present work, the uncoupling activity of sertraline on the respiratory chain, associated with a fast energetic collapse of the parasite, followed by a general metabolic disarray were pinpointed as important components to the leishmanicidal mechanisms of SRT. Despite SRT being a cationic amphiphile, neither massive structural damage of the plasma membrane nor entry of the vital dye SYTOX Green at the concentrations of SRT assayed were observed. Hence, a nonspecific and severe plasma membrane damage as the primary source for the metabolic disarray SRT due to its cationic amphiphilic character was ruled out.

Figure S6 summarizes the hypothetical scenario proposed for the leishmanicidal activity of sertraline. In an initial step, sertraline acts as a mild uncoupling agent of the respiratory chain, impairing the mitochondrial production of ATP, the main bioenergetic source for Leishmania and increasing ROS production, caused by the electron leakage throughout the respiratory chain. The shortage of ATP leads to plasma membrane depolarization, jeopardizing the nutrient transport driven by membrane potential. Finally, the ensuing oxidative stress prompted a general metabolic disarray, accounting for the morphological damage observed at later stages of its lethal mechanism.

This bioenergetic disarray is additionally supported by the metabolic profiling of SRT-treated parasites. SRT decreased the levels of aspartate and proline, two important metabolic fuels for the Krebs cycle in Leishmania (43), as well as of glutamate, a hub for many metabolic pathways (43). Changes in the lysophospholipid pattern of promastigotes were induced by SRT. A feasible interpretation is the generation of fatty acids from the resulting phospholipid degradation as an alternative metabolic source to feed the Krebs cycle, as described in amastigotes (35). In any case, it would be only partially successful. SRT induced a decrease in the levels of succinate, the main substrate for the respiratory chain, since complex I scarcely contributes to the respiration of Leishmania (44).

A faulty mitochondrial production of ATP in Leishmania may be partially offset by an increase in the glycolytic activity, as described in parasites resistant to tafenoquine, a drug inhibitor of the respiratory chain of the parasite (45). In SRT-treated promastigotes the levels of hexose-phosphates, likely involving glucose-6-phosphate as one of the most abundant, decreased. If so, even partial relief by glycolysis of the energetic collapse of the parasite by SRT would be unlikely.

The impact of an oxidative stress will be worsened under a deficient detoxification of the ROS produced. The decrease in the levels of sedoheptulose-6-phosphate suggests a lower metabolic flow across the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), since hexose-6-phosphate, a metabolite shared with glycolysis, is also the first metabolite of PPP. In Leishmania under oxidative stress, the use of glucose by glycolysis is partially diverted into the PPP in order to ensure an adequate supply of NADPH (46), the sole coenzyme used by trypanothione reductase to maintain reduced trypanothione (bis-glutathionyl spermidine), the ultimate supplier of reducing equivalents to ROS detoxifying enzymes (47, 48). Interestingly, SRT treatment decreased trypanothione levels in promastigotes, whereas the glutathione pool rose up severalfold. The same metabolic trend was described for Leishmania under oxidative stress due to either cis-diaminedichloroplatinum (II) (49) or to hypericin (50), as well as under blockade of spermidine biosynthesis at the level of ornithine decarboxylase (50, 51). Similar to SRT-treated parasites, ornithine decarboxylase knockout parasites maintained spermidine levels, while arginine and putrescine, its two immediate biosynthetic precursors, decreased. A reversal degradation of trypanothione into glutathione plus spermidine was proposed to ensure an adequate level of spermidine, involved in the biosynthesis of hypusine, a modified essential amino acid for Leishmania (51, 52).

Interestingly, indatraline, another monoamine neurotransmitter reuptake inhibitor, with partial structural resemblance to SRT, inhibited the trypanothione reductase of Trypanosoma brucei (53). If the same effect occurs in Leishmania, the oxidative stress caused by SRT will be further enhanced, not only by avoidance of glucose retooling into PPP with a decreased NADPH supply, but also by a feasible inhibition of trypanothione reductase.

Sertraline was a poor inducer of resistance in Leishmania; after 8 months of in vitro growth of the parasites under constant a SRT pressure, the IC50 only increased slightly. Moreover, SRT worked as a sensitizer in bacteria (22) and in tumoral cell lines (31). If this effect in Leishmania also occurs, not only would SRT be a very weak resistance inducer, but it would also be as an excellent candidate for combination therapies with drugs whose resistance is in whole or in part based on drug efflux by ABC transporters, e.g., organic antimonials or miltefosine (5). In addition, the increase in the level of glutathione due to SRT may presumably favor the conversion of the prodrug Sb(V) into Sb(III) (54), since Sb(V)-glutathione adducts are the substrate of the thiol-dependent reductase 1.

The complexity of the changes in the metabolome and the morphological damage induced by SRT in Leishmania makes unlikely the uncoupling of Leishmania mitochondrion as the sole target for this drug, accounting for the scarce induction of resistance. Similar to the microbicidal activity of other uncouplers (55), the lethal activity of SRT will presumably involved additional targets not yet unveiled. Although the present study was carried out on promastigotes, SRT was active both on intracellular amastigotes of L. infantum, in agreement with the data obtained previously on L. donovani amastigotes (26). Despite the severe metabolic retooling between promastigote and amastigote, the differential changes among them mostly affect to the sources of the metabolic fuel, rather than to the mitochondrial machinery in charge of ATP synthesis. In fact, a higher relevance for mitochondrial metabolism on L. mexicana amastigotes was reported (35). We have confirmed that the mitochondrial depolarization observed on L. infantum promastigotes, also occurred on L. pifanoi axenic amastigotes, a well-established axenic line with very high resemblance to amastigotes of the same species isolated from animal lesions (36), and selected for its higher homogeneity and reproducibility over the L. infantum axenic amastigotes obtained by us. This is an initial support to endorse a general leishmanicidal mechanism for SRT encompassing at least the cutaneous L. pifanoi, as well as the visceral L. donovani (26) and L. infantum species.

In all, sertraline appears as an appealing candidate for drug repurposing in leishmaniasis, with good prospects for its future implementation, such as low cost, scarce and mild side effects, and well-known pharmacology, as well as for its inclusion in combination therapies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and reagents.

Unless otherwise stated, chemicals and reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich-Spain (Madrid, Spain). Fluorescent probes SYTOX Green, rhodamine-123 [2-(6-amino-3-imino-3H-xanthen-9-yl) benzoic acid methyl ester, chloride], DMNPE-luciferin [d-luciferin 1-(4, 5-dimethoxy-2-nitrophenyl) ethyl ester], bisoxonol [bis-(1,3-diethylthiobarbituric) trimethine oxonol], and MitoSOX [3,8-phenanthridinediamine, 5-(6′-triphenylphosphoniumhexyl)-5,6 dihydro-6-phenyl] were purchased from Invitrogen (Barcelona, Spain).

Leishmania parasites and mammalian cells.

L. infantum promastigotes (JPC strain; National Center for Microbiology, Majadahonda, Spain) were grown in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, Paisley, UK) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (HIFCS) at 26°C as described previously (34). L. infantum promastigotes transfected with a cytoplasmic form Photinus pyralis luciferase (3-Luc line) were obtained by electroporation with the expression vector pLEXSYHyg-Luc, kindly supplied by F. Gamarro (Instituto de Parasitología y Biomedicina López-Neyra CSIC, Granada) (56). To this end, 108 promastigotes in the logarithmic phase of growth plus 7 μg of the SwaI-linearized plasmid pLEXSYHyg-Luc plasmid, both resuspended in CytoMyx buffer (57), were mixed in a 0.4-cm Bio-Rad electroporation cuvette and electroporated in a GenePulser electroporation device (Bio-Rad; 1,500 V, 25 μF, 3.75 kV/cm, 200 Ω). Afterward, the parasites were washed twice in fresh growth medium and, after 24 h, transfected parasites were selected by growth under increasing pressure with up to 100 μg/ml hygromycin B (56). L. infantum amastigotes were obtained from the spleens of previously infected golden hamsters (60 to 70 days postinfection) by differential centrifugation (58). L. pifanoi axenic amastigotes (strain MHOM/VE/60/Ltrod) were grown in 199 medium (Gibco-BRL) plus 20% HIFCS at 32°C (34).

Peritoneal macrophages (Mϕ) were obtained from BALB/c mice by peritoneal washing with Hanks medium. Cells were seeded at 105/well in 16-well slides (Nunc-Thermo Fisher Scientific) and allowed to adhere (24 h, 37°C, 5% CO2). The infection was proceeded in a 1:10 ratio of Mϕ to amastigotes in RPMI 1640–10% HIFCS during 24 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2-humidified incubator. Noninternalized amastigotes were removed by washing and infected Mϕ treated with sertraline during 72 h under the same conditions. Animal procedures were performed with the approval of the Research Ethics Commission (CEUA-IAL-Pasteur 05/2011), in agreement with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals from the National Academy of Sciences.

Assessment of the leishmanicidal activity of sertraline.

Parasites were harvested at late exponential growth phase. Promastigotes were allowed to proliferate in the presence of SRT in a 96 microwell plate (2 × 106 cells/ml, 200 μl/well), and growth was assessed colorimetrically by MTT reduction (34).

To address the leishmanicidal mechanism of SRT, promastigotes were resuspended in HBSS-Glc at 2 × 107 cells/ml, which was defined as the standard condition. Sertraline cytotoxicity on Leishmania was evaluated by inhibition of MTT reduction, measured either immediately after 4 h of incubation. Samples were made by triplicate and experiments repeated at least twice. Inhibitory concentration x (ICx) was defined as the concentration of drug required to inhibit MTT reduction in an x percentage respect to untreated parasites. This was determined using the GraphPad Prism software statistical package.

Sertraline cytotoxicity against BALB/c murine peritoneal macrophages.

Cells were seeded into a 96-well culture microplate (105 cells/well). Once attached, they were incubated with SRT in growth medium (37°C, 24 h), and inhibition of MTT reduction was assessed as described above (34).

Variation of ATP levels in 3-Luc L. infantum promastigotes.

Real-time variation of the intracellular levels of free cytoplasmic ATP by sertraline was assessed in living promastigotes of the L. infantum 3-Luc strain that express a cytoplasmic form of firefly luciferase, in the presence of 25 μM DMNPE-luciferin, under the standard conditions (32).

Permeation of the plasma membrane of promastigotes by sertraline.

Plasma membrane depolarization and entrance of the vital dye were assayed fluorometrically in a microplate assay using bisoxonol and SYTOX Green as fluorescent probes, respectively, as described earlier (34).

Determination of mitochondrial functional parameters in sertraline-treated parasites.

Variation of Δψm was monitored by cytofluorimetry, measuring Rh123 accumulation into the parasites, as reported (34). Oxygen consumption rates for promastigotes were measured polarographycally using a Clark’s oxygen electrode (Hansatech, King’s Lynn, UK) at 108 × cells/ml. If required, parasites were treated with 60 µM digitonin to allow free access of inhibitors and substrates to the mitochondrion. The mitochondrial production of superoxide (O2−) was assessed with the fluorogenic mitochondrial probe MitoSOX Red (59). Morphological changes induced by SRT on promastigotes were visualized by confocal microscopy using the mitochondrial marker MitoTracker Red (33).

Transmission electron microscopy.

Promastigotes were incubated with SRT at its IC50 (20 µM) in HBSS-Glc under the standard conditions. Parasites were processed by glutaraldehyde and OsO4 fixation, progressively dehydrated with ethanol, included in Epon812 resin, and observed in a JEOL JEM-1230 microscope (34).

Metabolomics.

A detailed description of the methodology used in this work was included in in the supplemental material. Promastigotes were incubated with 35 µM SRT (IC70) for 12 h in full growth medium as reported elsewhere (60, 61). Metabolites were extracted with MeOH/H2O at 4:1 (vol/vol) and analyzed by LC-MS (ESI+ and ESI–) and CE-MS. Experimental details are included in in the supplemental material. Compounds were identified after processing as described earlier (60, 61). Allocation of metabolites into the respective metabolic pathways was carried out using KEGG (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/genome.html) and LeishCyc (https://biocyc.org/organism-summary?object=LEISH ).

Statistical analysis.

Unless otherwise stated, samples were tested in triplicates, and at least two independent experiments were carried out. Statistical significance was determined by Student t test (P < 0.05) using the statistical package of SigmaPlot versus 11.0. Specific statistical procedures for analysis of metabolomics data are included in the supplemental material.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Vanesa Alonso for excellent analytical assistance, Joanna Godzien for expertise and help in tandem mass spectrometry analysis, and Maite Seisdedos, Fernando González, and Begoña Pou for help in confocal and electron microscopy.

This study was supported by grants from the Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias-ISCIII-FEDER (PI12-02706 and RD16/0027/0010); the Red de Enfermedades Tropicales, subprogram RETICS del Plan Estatal de I+D+i (2013-2016), cofinanced with FEDER funds (SAF2015-65740-R and CSIC grant PIE 201620E038 to L.R.); the São Paulo State Research Foundation (FAPESP 2015/23403-9 to A.G.T.); the EADS-CASA/Brazilian Air Force (FAB) mobility program (M.L.L.); and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (to M.L.L.). The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01928-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arenas R, Torres-Guerrero E, Quintanilla-Cedillo MR, Ruiz-Esmenjaud J. 2017. Leishmaniasis: a review. F1000 Res 6:750. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.11120.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sundar S, Singh A. 2018. Chemotherapeutics of visceral leishmaniasis: Present and future developments. Parasitology 145:481–489. doi: 10.1017/S0031182017002116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomaz-Soccol V, da Costa ESF, Karp SG, Letti LAJ, Soccol FT, Soccol CR. 2018. Recent advances in vaccines against Leishmania based on patent applications. Recent Pat Biotechnol 12:21–32. doi: 10.2174/1872208311666170510121126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iborra S, Solana JC, Requena JM, Soto M. 2018. Vaccine candidates against Leishmania under current research. Expert Rev Vaccines 17:323–334. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2018.1459191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ponte-Sucre A, Gamarro F, Dujardin JC, Barrett MP, López-Vélez R, García-Hernández R, Pountain AW, Mwenechanya R, Papadopoulou B. 2017. Drug resistance and treatment failure in leishmaniasis: a 21st century challenge. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 11:e0006052. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mosimann V, Neumayr A, Paris DH, Blum J. 2018. Liposomal amphotericin B treatment of Old World cutaneous and mucosal leishmaniasis: a literature review. Acta Trop 182:246–250. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2018.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Musa AM, Younis B, Fadlalla A, Royce C, Balasegaram M, Wasunna M, Hailu A, Edwards T, Omollo R, Mudawi M, Kokwaro G, El-Hassan A, Khalil E. 2010. Paromomycin for the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis in Sudan: a randomized, open-label, dose-finding study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 4:e855. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sundar S, Jha TK, Thakur CP, Engel J, Sindermann H, Fischer C, Junge K, Bryceson A, Berman J. 2002. Oral miltefosine for Indian visceral leishmaniasis. N Engl J Med 347:1739–1746. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramesh V, Singh R, Avishek K, Verma A, Deep DK, Verma S, Salotra P. 2015. Decline in clinical efficacy of oral miltefosine in treatment of post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL) in India. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 9:e0004093. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mesquita JT, Tempone AG, Reimão JQ. 2014. Combination therapy with nitazoxanide and amphotericin B, Glucantime®, miltefosine, and sitamaquine against Leishmania infantum intracellular amastigotes. Acta Trop 130:112–116. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Griensven J, Balasegaram M, Meheus F, Alvar J, Lynen L, Boelaert M. 2010. Combination therapy for visceral leishmaniasis. Lancet Infect Dis 10:184–194. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andrews KT, Fisher G, Skinner-Adams TS. 2014. Drug repurposing and human parasitic protozoan diseases. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist 4:95–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andrade-Neto VV, Cunha-Junior EF, Dos Santos Faioes V, Martins TP, Silva RL, Leon LL, Torres-Santos EC. 2018. Leishmaniasis treatment: Update of possibilities for drug repurposing. Front Biosci 23:967–996. doi: 10.2741/4629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cappuccino EF, Stauber LA. 1959. Some compounds active against experimental visceral leishmaniasis. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 101:742–744. doi: 10.3181/00379727-101-25080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smorenburg CH, Seynaeve C, Bontenbal M, Planting AS, Sindermann H, Verweij J. 2000. Phase II study of miltefosine 6% solution as topical treatment of skin metastases in breast cancer patients. Anticancer Drugs 11:825–828. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200011000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neal RA. 1968. The effect of antibiotics of the neomycin group on experimental cutaneous leishmaniasis. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 62:54–62. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1968.11686529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patterson S, Wyllie S, Norval S, Stojanovski L, Simeons FRC, Auer JL, Osuna-Cabello M, Read KD, Fairlamb AH. 2016. The anti-tubercular drug delamanid as a potential oral treatment for visceral leishmaniasis. Elife 5:e09744. doi: 10.7554/eLife.09744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mowbray CE. 2018. Anti-leishmanial drug discovery: past, present, and future perspectives, p 24–36. In Rivas L, Gil C (ed), Drug discovery for leishmaniasis RSC drug discovery series. Royal Society of Chemistry, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van den Kerkhof M, Mabille D, Chatelain E, Mowbray CE, Braillard S, Hendrickx S, Maes L, Caljon G. 2018. In vitro and in vivo pharmacodynamics of three novel antileishmanial lead series. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist 8:81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2018.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeVane CL, Liston HL, Markowitz JS. 2002. Clinical pharmacokinetics of sertraline. Clin Pharmacokinet 41:1247–1266. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200241150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mandrioli R, Mercolini L, Raggi MA. 2013. Evaluation of the pharmacokinetics, safety and clinical efficacy of sertraline used to treat social anxiety. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 9:1495–1505. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2013.816675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bohnert JA, Szymaniak-Vits M, Schuster S, Kern WV. 2011. Efflux inhibition by selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in Escherichia coli. J Antimicrob Chemother 66:2057–2060. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar VS, Sharma VL, Tiwari P, Singh D, Maikhuri JP, Gupta G, Singh MM. 2006. The spermicidal and antitrichomonas activities of SSRI antidepressants. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 16:2509–2512. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.01.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Läss-Florl C, Dierich MP, Fuchs D, Semenitz E, Jenewein I, Ledochowski M. 2001. Antifungal properties of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors against Aspergillus species in vitro. J Antimicrob Chemother 48:775–779. doi: 10.1093/jac/48.6.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lass-Flörl C, Ledochowski M, Fuchs D, Speth C, Kacani L, Dierich MP, Fuchs A, Würzner R. 2003. Interaction of sertraline with Candida species selectively attenuates fungal virulence in vitro. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 35:11–15. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(02)00422-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palit P, Ali N. 2008. Oral therapy with sertraline, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, shows activity against Leishmania donovani. J Antimicrob Chemother 61:1120–1124. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johansen LM, DeWald LE, Shoemaker CJ, Hoffstrom BG, Lear-Rooney CM, Stossel A, Nelson E, Delos SE, Simmons JA, Grenier JM, Pierce LT, Pajouhesh H, Lehár J, Hensley LE, Glass PJ, White JM, Olinger GG. 2015. A screen of approved drugs and molecular probes identifies therapeutics with anti-Ebola virus activity. Sci Transl Med 7:290ra289. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa5597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim SW, Park SY, Hwang O. 2002. Up-regulation of tryptophan hydroxylase expression and serotonin synthesis by sertraline. Mol Pharmacol 61:778–785. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.4.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang H, Goehring A, Wang KH, Penmatsa A, Ressler R, Gouaux E. 2013. Structural basis for action by diverse antidepressants on biogenic amine transporters. Nature 503:141–145. doi: 10.1038/nature12648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamashita A, Singh SK, Kawate T, Jin Y, Gouaux E. 2005. Crystal structure of a bacterial homologue of Na+/Cl–-dependent neurotransmitter transporters. Nature 437:215–223. doi: 10.1038/nature03978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Drinberg V, Bitcover R, Rajchenbach W, Peer D. 2014. Modulating cancer multidrug resistance by sertraline in combination with a nanomedicine. Cancer Lett 354:290–298. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luque-Ortega JR, Rivero-Lezcano OM, Croft SL, Rivas L. 2001. In vivo monitoring of intracellular ATP levels in Leishmania donovani promastigotes as a rapid method to screen drugs targeting bioenergetic metabolism. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 45:1121–1125. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.4.1121-1125.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luque-Ortega JR, van't Hof W, Veerman EC, Saugar JM, Rivas L. 2008. Human antimicrobial peptide histatin 5 is a cell-penetrating peptide targeting mitochondrial ATP synthesis in Leishmania. FASEB J 22:1817–1828. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-096081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luque-Ortega JR, Rivas L. 2010. Characterization of the leishmanicidal activity of antimicrobial peptides. Methods Mol Biol 618:393–420. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-594-1_25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saunders EC, Ng WW, Kloehn J, Chambers JM, Ng M, McConville MJ. 2014. Induction of a stringent metabolic response in intracellular stages of Leishmania mexicana leads to increased dependence on mitochondrial metabolism. PLoS Pathog 10:e1003888. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pan AA, Duboise SM, Eperon S, Rivas L, Hodgkinson V, Traub-Cseko Y, McMahon-Pratt D. 1993. Developmental life cycle of Leishmania: cultivation and characterization of cultured extracellular amastigotes. J Eukaryotic Microbiology 40:213–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1993.tb04906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Singh S, Dinesh N, Kaur PK, Shamiulla B. 2014. Ketanserin, an antidepressant, exerts its antileishmanial action via inhibition of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase (HMGR) enzyme of Leishmania donovani. Parasitol Res 113:2161–2168. doi: 10.1007/s00436-014-3868-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dinesh N, Kaur PK, Swamy KK, Singh S. 2014. Mianserin, an antidepressant kills Leishmania donovani by depleting ergosterol levels. Exp Parasitol 144:84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cunha-Júnior EF, Andrade-Neto VV, Lima ML, da Costa-Silva TA, Galisteo Junior AJ, Abengózar MA, Barbas C, Rivas L, Almeida-Amaral EE, Tempone AG, Torres-Santos EC. 2017. Cyclobenzaprine raises ROS levels in Leishmania infantum and reduces parasite burden in infected mice. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 11:e0005281. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zilberstein D, Dwyer DM. 1984. Antidepressants cause lethal disruption of membrane function in the human protozoan parasite Leishmania. Science 226:977–979. doi: 10.1126/science.6505677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen J, Korostyshevsky D, Lee S, Perlstein EO. 2012. Accumulation of an antidepressant in vesiculogenic membranes of yeast cells triggers autophagy. PLoS One 7:e34024. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schump MD, Fox DM, Bertozzi CR, Riley LW. 2017. Subcellular partitioning and intramacrophage selectivity of antimicrobial compounds against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e01639–e01616. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01639-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saunders EC, Ng WW, Chambers JM, Ng M, Naderer T, Kromer JO, Likic VA, McConville MJ. 2011. Isotopomer profiling of Leishmania mexicana promastigotes reveals important roles for succinate fermentation and aspartate uptake in tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) anaplerosis, glutamate synthesis, and growth. J Biol Chem 286:27706–27717. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.213553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Opperdoes FR, Michels PA. 2008. Complex I of Trypanosomatidae: does it exist? Trends Parasitol 24:310–317. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Manzano JI, Carvalho L, Perez-Victoria JM, Castanys S, Gamarro F. 2011. Increased glycolytic ATP synthesis is associated with tafenoquine resistance in Leishmania major. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:1045–1052. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01545-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ghosh AK, Sardar AH, Mandal A, Saini S, Abhishek K, Kumar A, Purkait B, Singh R, Das S, Mukhopadhyay R, Roy S, Das P. 2015. Metabolic reconfiguration of the central glucose metabolism: a crucial strategy of Leishmania donovani for its survival during oxidative stress. FASEB J 29:2081–2098. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-258624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Flohe L. 2013. The fairytale of the GSSG/GSH redox potential. Biochim Biophys Acta 1830:3139–3142. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bombaça ACS, Menna-Barreto RFS. 2017. The oxidative metabolism in trypanosomatids: Implications for these protozoa biology and perspectives for drugs development, p 93–129. In Leon L, Torres-Santos EC (ed), Different aspects on chemotherapy of trypanosomatids. Nova Science Publishers, Inc, Hauppauge, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tavares J, Ouaissi M, Ouaissi A, Cordeiro-da-Silva A. 2007. Characterization of the anti-Leishmania effect induced by cisplatin, an anticancer drug. Acta Trop 103:133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Singh S, Sarma S, Katiyar SP, Das M, Bhardwaj R, Sundar D, Dubey VK. 2015. Probing the molecular mechanism of hypericin-induced parasite death provides insight into the role of spermidine beyond redox metabolism in Leishmania donovani. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:15–24. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04169-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jiang Y, Roberts SC, Jardim A, Carter NS, Shih S, Ariyanayagam M, Fairlamb AH, Ullman B. 1999. Ornithine decarboxylase gene deletion mutants of Leishmania donovani. J Biol Chem 274:3781–3788. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.6.3781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chawla B, Jhingran A, Singh S, Tyagi N, Park MH, Srinivasan N, Roberts SC, Madhubala R. 2010. Identification and characterization of a novel deoxyhypusine synthase in Leishmania donovani. J Biol Chem 285:453–463. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.048850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Walton JG, Jones DC, Kiuru P, Durie AJ, Westwood NJ, Fairlamb AH. 2011. Synthesis and evaluation of indatraline-based inhibitors for trypanothione reductase. ChemMedChem 6:321–328. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201000442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fyfe PK, Westrop GD, Silva AM, Coombs GH, Hunter WN. 2012. Leishmania TDR1 structure, a unique trimeric glutathione transferase capable of deglutathionylation and antimonial prodrug activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:11693–11698. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202593109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Feng X, Zhu W, Schurig-Briccio LA, Lindert S, Shoen C, Hitchings R, Li J, Wang Y, Baig N, Zhou T, Kim BK, Crick DC, Cynamon M, McCammon JA, Gennis RB, Oldfield E. 2015. Anti-infectives targeting enzymes and the proton motive force. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:E7073–E7082. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1521988112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.García-Hernández R, Gómez-Pérez V, Castanys S, Gamarro F. 2015. Fitness of Leishmania donovani parasites resistant to drug combinations. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 9:e0003704. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van den Hoff MJ, Moorman AF, Lamers WH. 1992. Electroporation in 'intracellular' buffer increases cell survival. Nucleic Acids Res 20:2902. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.11.2902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tempone AG, Ferreira DD, Lima ML, Costa Silva TA, Borborema SET, Reimao JQ, Galuppo MK, Guerra JM, Russell AJ, Wynne GM, Lai RYL, Cadelis MM, Copp BR. 2017. Efficacy of a series of α-pyrone derivatives against Leishmania infantum and Trypanosoma cruzi. Eur J Med Chem 139:947–960. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.08.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Piacenza L, Irigoin F, Alvarez MN, Peluffo G, Taylor MC, Kelly JM, Wilkinson SR, Radi R. 2007. Mitochondrial superoxide radicals mediate programmed cell death in Trypanosoma cruzi: cytoprotective action of mitochondrial iron superoxide dismutase overexpression. Biochem J 403:323–334. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Canuto GAB, Castilho-Martins EA, Tavares MFM, Rivas L, Barbas C, López-Gonzálvez Á. 2014. Multi-analytical platform metabolomic approach to study miltefosine mechanism of action and resistance in Leishmania. Anal Bioanal Chem 406:3459–3476. doi: 10.1007/s00216-014-7772-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rojo D, Canuto GAB, Castilho-Martins EA, Tavares MFM, Barbas C, López-Gonzálvez Á, Rivas L. 2015. A multiplatform metabolomic approach to the basis of antimonial action and resistance in Leishmania infantum. PLoS One 10:e0130675. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0130675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.