Abstract

To describe a rare case of an unusual visual threatening complication of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). A 21-year-old male visited the hospital complaining of 1-week painless binocular acute visual loss without any other symptoms. The patient was diagnosed with CML. He then received emergent leukapheresis with imatinib treatment, which achieved obvious hematological remission. However, the visual acuity did not recover along with the CML remission and ocular structure relief. CML-related leukostasis could induce severe leukostasis retinopathy. Hematologists and ophthalmologists should pay more attention to this relatively rare and severe complication of CML.

Keywords: Chronic myeloid leukemia, hemorrhagic retinal detachment, leukostasis

Leukostasis retinopathy caused by severe hyperleukocytosis is an unusual complication of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) referred to retinal ischemia.[1–8] Herein, we first describe a rare CML case with bilateral visual loss caused by severe leukostasis.

Case Report

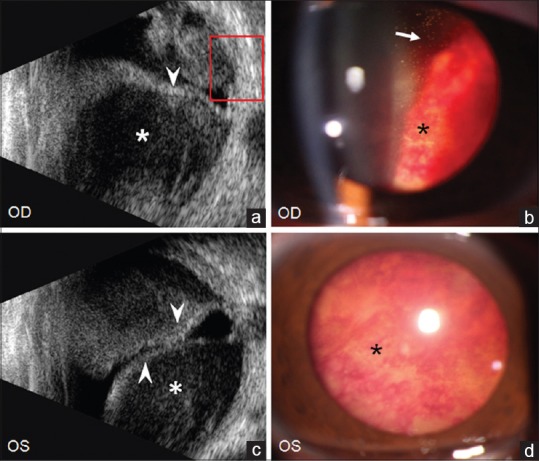

A 21-year-old male visited our hospital complaining of 1-week painless binocular acute visual loss without any other symptoms. Visual acuity was no light perception (NLP) in the right eye and hand motion (HM) in the left eye. Pupillary light reflex of the right eye was completely absent with a pupil diameter of 5.5 mm; the reflex was sluggish in the left eye with a pupil diameter of 3.5 mm. Both anterior segments were normal and bilateral vitreous bodies were hazy with gray and white particles [Fig. 1]. Behind the vitreous bodies, extensive retinal detachments, extremely tortuous retinal vessels and diffuse retinal bleeding were observed [Fig. 1]. B-scan ultrasonography showed thickened choroid and complete retinal detachment, as well as hyperechoic homogeneous amorphous mass in subretinal space [Fig. 1].

Figure 1.

The initial ultrasound (a and c) and slit-lamp photography (b and d) of bilateral eyes. Many gray and white particles (arrows in b) in vitreous body, diffuse retinal hemorrhages (black asterisk in b and d), complete retinal detachments (arrow heads in a and c) and extensive subretinal hemorrhage (white asterisk in a and c) were observed in both the eyes

To determine the causes, the following examinations were taken under the consent of the patient. Routine blood test showed: white blood cells (WBC) count, 640.34 × 109/L; neutrophil count, 613.46 × 109/L; hemoglobin, 86.0 g/L; hematocrit, 23%; platelet count, 180 × 109/L. One day after admission, the patient was transferred to the Department of Hematology and Oncology. Both bone marrow examination and BCR/ABL fusion gene test confirmed the diagnosis of CML. And then the patient received emergent leukapheresis with imatinib treatment, which achieved obvious hematological remission.

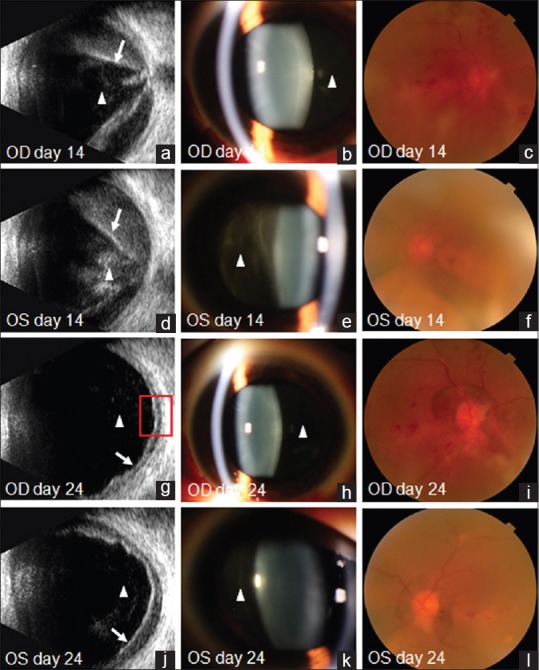

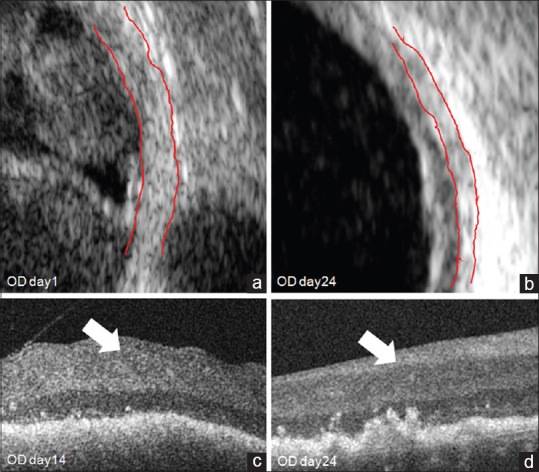

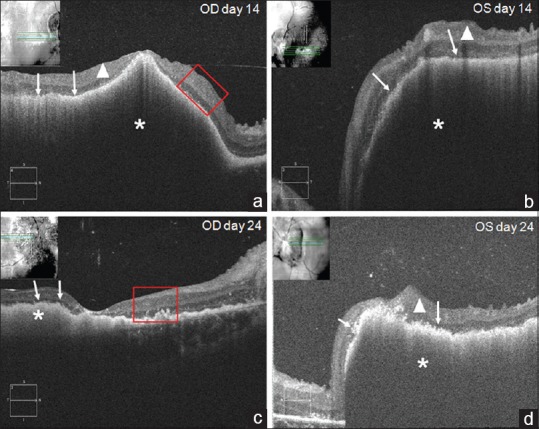

Fourteen days after imatinib treatment, the particles in vitreous and retinal detachments were partially relieved but the visual acuity was still NLP in the right eye and only light perception (LP) in the left eye. He then received drainage of subretinal fluid in the right eye. Afterwards the subretinal mass was identified as a dark brown hemorrhage. However, the subretinal hemorrhage manifested as blood cell debris without any intact cells under the microscope. Instead of surgical intervention, the left eye received 500 mg methylprednisolone pulse therapy from the 3rd day after surgery. Twenty four days after imatinib treatment, the gray particles in the vitreous and diffused retinal hemorrhages were almost absorbed [Fig. 2]. Re-inspected B-ultrasonography showed the normalized choroid thickness and almost reattachment of retina as well as obvious reduction of subretinal hemorrhage in both the eyes [Figs. 2 and 3]. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) also revealed dramatical subretinal hemorrhage resorption, neuro-retinal inner layers blurry and disturbance of the IS/OS layers [Figs. 3 and 4]. Unfortunately, the patient's vision was not able to recover and finally became NLP in both the eyes.

Figure 2.

The images at day 14 (a–f) and day 24 (g–l) after imatinib treatment, the particles in vitreous (triangles in a, b, d, e, g, h, j and k), retinal hemorrhages and detachments (arrows in a, d, g and j) were dramatically relieved. The optic clarity at day 24 (i and l) was much more improved than that of day 14 (c and f). With subretinal hemorrhage drainage, the retinal detachment in right eye recovered faster and more complete than the left eye

Figure 3.

The magnifying images of red frames in Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 4. The choroid of right eye was extremely thickened at day 1 (a) compared to day 24 (b) after imatinib treatment (red lines). The optical coherence tomography showed the blurring of retinal nerve fiber layer boundary which implied the edema of retinal inner layers (arrows in c and d)

Figure 4.

The dynamic changes of the retina from day 14 (a and b) to day 24 (c and d) after imatinib treatment by optical coherence tomography. Continuous optical coherence tomography revealed dramatically resorbed subretinal hemorrhage (asterisk in a–d), neuro-retinal inner layers edema (triangles in a, b and d), disturbance of the IS/OS layers and thinned out layers (arrows in a–d)

Discussion

Unlike the common signs of exudative retinal detachment, this CML patient manifested unusual serious hemorrhagic retinal detachment, extremely tortuous retinal vessels, diffuse retinal bleeding and deteriorated binocular visual loss even with aggressive treatment. The characteristic manifestation and poor outcome suggested that the mechanism of retinopathy in this case was quite different. Hyperleukocytosis is the crucial clinical manifestation of CML, which can result in local circulatory stasis. It has been reported that ocular complications are related to retinal ischemia caused by leukostasis in CML.[1,2,3,5,8] All of these complications were collectively referred to “Leukostasis Retinopathy”. This patient was unable to take fluorescence fundus angiography due to extremely high WBC count and a positive allergy test for fluorescence. Nevertheless, thickened choroid, extensive hemorrhagic retinal detachment, diffuse retinal bleeding and obviously tortuous retinal vessels could indicate a severe microcirculation stasis which was much more severe than ever reported. Thereafter the accumulated blood cells including leukemia cells could exudate into the subretinal space, leading to the observed hemorrhagic retinal detachment. However, the specific cell type in subretinal hemorrhage could not be identified in this case due to the severe damage of cells. One of the potential reasons was the delayed surgery performed 2 weeks after hematologic therapy. The anti-tumor drugs might have already destroyed the tumor cells during 2 weeks. Thus, drainage of subretinal fluid should be performed earlier in order to clarify the causes and mechanisms of subretinal bleeding in CML. The increased reflection and blurry structure of inner retinal layers on OCT was quite similar to acute central retinal artery occlusion, manifested by inner retinal layer edema.[9] This phenomenon demonstrated a severe arterial ischemic situation caused by retinal microvascular stasis. In addition, the arterial ischemia could also explain the reason of rapidly deteriorated vision and poor binocular pupil reaction in this patient.

With the hematological remission and drainage of subretinal fluid, the retinal detachment and retinal bleeding were gradually relieved. However, the poor outcome was observed in both the eyes. We first considered optic nerve damage may be an important impact for visual loss, but the patient's parent refused to use visual evoked potential (VEP) to exam the function. However, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) did not show obvious optic nerve abnormality, and his optic disc did not manifest as extremely swollen and pallor in different stages. So we speculated that the visual loss was due to extremely severe arterial retinal ischemia caused by the extensive microvascular stasis. Eight days after vision impairment is beyond the common therapeutic time window of arterial ischemia. Therefore, the early detection of CML-related leukostasis retinopathy is crucial and the ideal treatment should focus on reversing the circulatory stasis at the early stage.

Conclusion

CML may have urgent irreversible vision-threatening complications due to stasis of microcirculation. Hematologists and ophthalmologists need to cooperate to provide such patients with early intervention.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We thank the patient for allowing us to report his case.

References

- 1.Nobacht S, Vandoninck KF, Deutman AF, Klevering BJ. Peripheral retinal nonperfusion associated with chronic myeloid leukemia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;135:404–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)01956-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Almeida DR, Chin EK, Grant LW. Chronic myelogenous leukemia presenting with bilateral optic disc neovascularization. Can J Ophthalmol. 2014;49:e68–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2014.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mandava N, Costakos D, Bartlett HM. Chronic myelogenous leukemia manifested as bilateral proliferative retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:576–7. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.4.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gokce M, Unal S, Bayrakçı B, Tuncer M. Chronic myeloid leukemia presenting with visual and auditory impairment in an adolescent: An insight to management strategies. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus. 2010;26:96–8. doi: 10.1007/s12288-010-0026-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Montero J, Cervera E, Palomares P, Amselem L, Diaz-Llopis M. Serous retinal detachment as a presenting feature of chronic myelogenous leukemia. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2010;4:394–6. doi: 10.1097/ICB.0b013e3181b5ef71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Macedo MS, Figueiredo AR, Ferreira NN, Barbosa IM, Furtado MJ, Correia NF, et al. Bilateral proliferative retinopathy as the initial presentation of chronic myeloid leukemia. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2013;20:353–6. doi: 10.4103/0974-9233.120016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Awh CC, Miller JB, Wu DM, Eliott D. Leukostasis retinopathy: A new clinical manifestation of chronic myeloid leukemia with severe hyperleukocytosis. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2015;46:768–70. doi: 10.3928/23258160-20150730-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohamed M, Oakley C, McEwen F, Connelley G. Leucapheresis for management of retinopathy in chronic myeloid leukaemia. BMJ Case Rep 2015. 2015 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-212889. pii: bcr2015212889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shah VA, Wallace B, Sabates NR. Spectral domain optical coherence tomography findings of acute branch retinal artery occlusion from calcific embolus. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2010;58:523–4. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.71703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]